Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions

Sources of Funding: The workshop was planned and conducted jointly by the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology with financial support from the American Academy of Periodontology Foundation, Colgate, Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc., Geistlich Biomaterials, SUNSTAR, and Procter & Gamble Professional Oral Health.

The proceedings of the workshop were jointly and simultaneously published in the Journal of Periodontology and Journal of Clinical Periodontology.

Abstract

A new periodontitis classification scheme has been adopted, in which forms of the disease previously recognized as “chronic” or “aggressive” are now grouped under a single category (“periodontitis”) and are further characterized based on a multi-dimensional staging and grading system. Staging is largely dependent upon the severity of disease at presentation as well as on the complexity of disease management, while grading provides supplemental information about biological features of the disease including a history-based analysis of the rate of periodontitis progression; assessment of the risk for further progression; analysis of possible poor outcomes of treatment; and assessment of the risk that the disease or its treatment may negatively affect the general health of the patient.

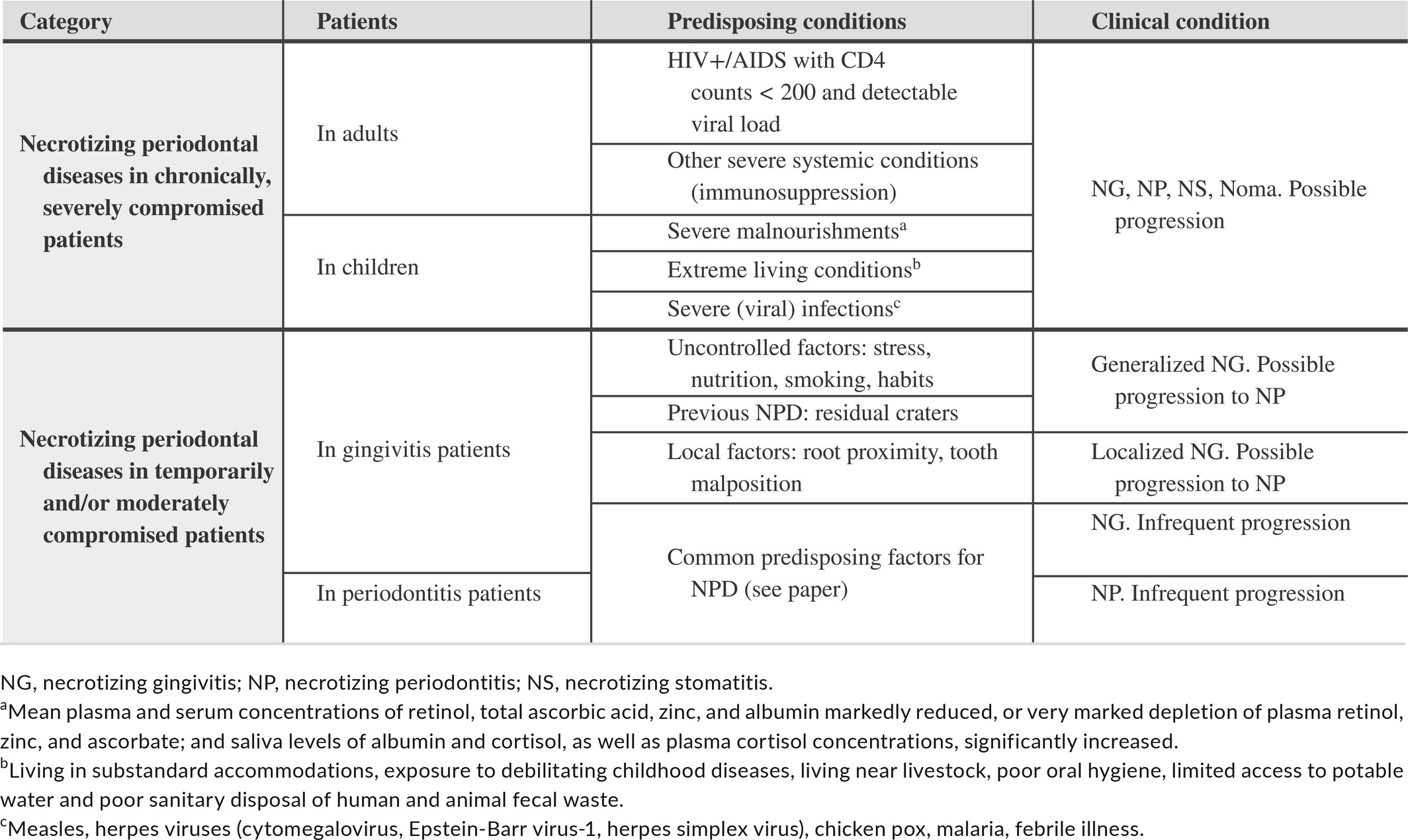

Necrotizing periodontal diseases, whose characteristic clinical phenotype includes typical features (papilla necrosis, bleeding, and pain) and are associated with host immune response impairments, remain a distinct periodontitis category.

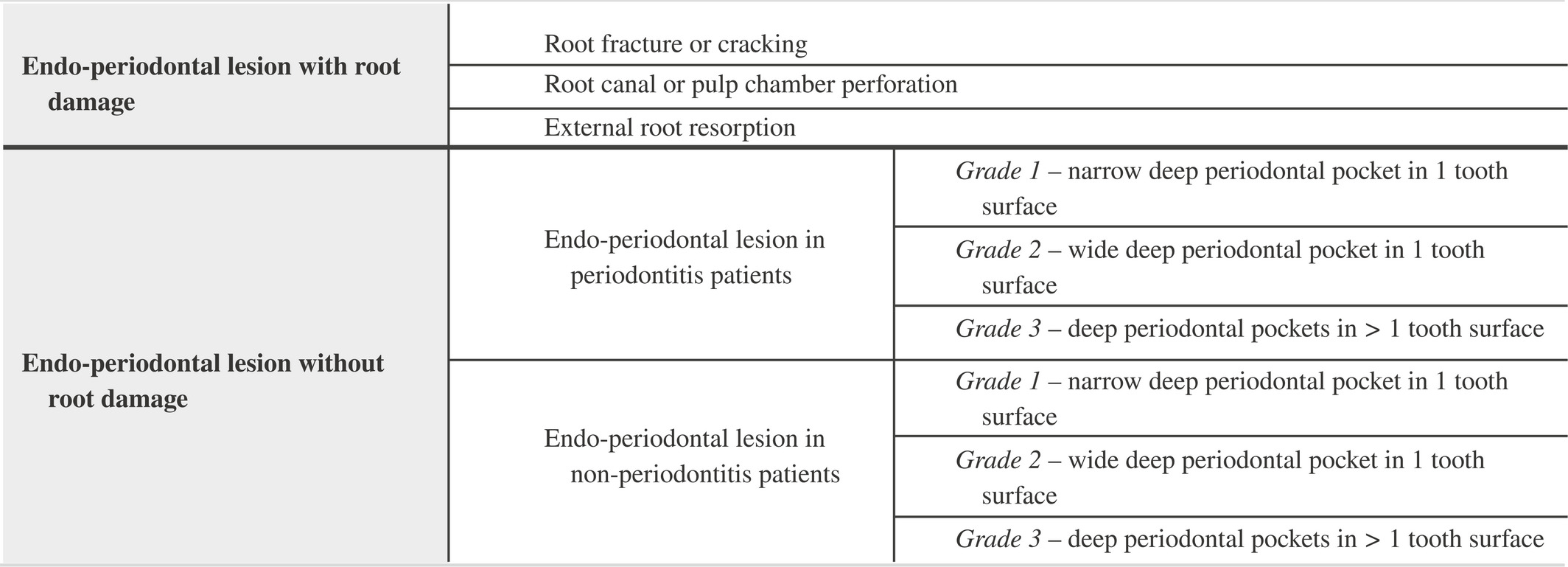

Endodontic-periodontal lesions, defined by a pathological communication between the pulpal and periodontal tissues at a given tooth, occur in either an acute or a chronic form, and are classified according to signs and symptoms that have direct impact on their prognosis and treatment.

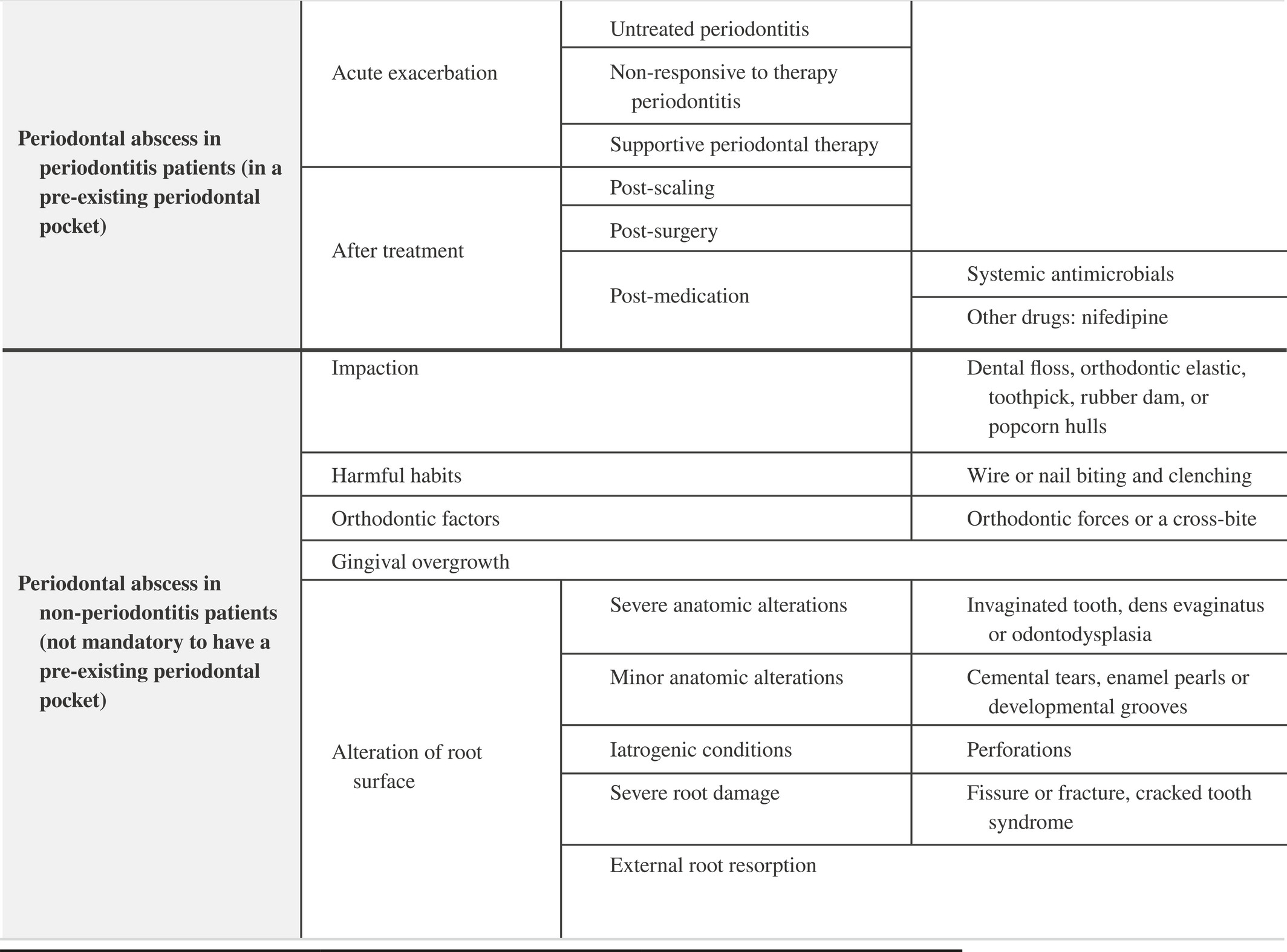

Periodontal abscesses are defined as acute lesions characterized by localized accumulation of pus within the gingival wall of the periodontal pocket/sulcus, rapid tissue destruction and are associated with risk for systemic dissemination.

Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic plaque biofilms and characterized by progressive destruction of the tooth-supporting apparatus. Its primary features include the loss of periodontal tissue support, manifested through clinical attachment loss (CAL) and radiographically assessed alveolar bone loss, presence of periodontal pocketing and gingival bleeding. Periodontitis is a major public health problem due to its high prevalence, as well as because it may lead to tooth loss and disability, negatively affect chewing function and aesthetics, be a source of social inequality, and impair quality of life. Periodontitis accounts for a substantial proportion of edentulism and masticatory dysfunction, results in significant dental care costs and has a plausible negative impact on general health.

- Chronic periodontitis, representing the forms of destructive periodontal disease that are generally characterized by slow progression

- Aggressive periodontitis, a diverse group of highly destructive forms of periodontitis affecting primarily young individuals, including conditions formerly classified as “early-onset periodontitis” and “rapidly progressing periodontitis”

- Periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease, a heterogeneous group of systemic pathological conditions that include periodontitis as a manifestation

- Necrotizing periodontal diseases, a group of conditions that share a characteristic phenotype where necrosis of the gingival or periodontal tissues is a prominent feature

- Periodontal abscesses, a clinical entity with distinct diagnostic features and treatment requirements

Although the above classification has provided a workable framework that has been used extensively in both clinical practice and scientific investigation in periodontology during the past 17 years, the system suffers from several important shortcomings, including substantial overlap and lack of clear pathobiology-based distinction between the stipulated categories, diagnostic imprecision, and implementation difficulties. The objectives of workgroup 2 were to revisit the current classification system of periodontitis, incorporate new knowledge relevant to its epidemiology, etiology and pathogenesis that has accumulated since the current classification's inception, and propose a new classification framework along with case definitions. To this end, five position papers were commissioned, authored, peer-reviewed, and accepted. The first reviewed the classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis (Fine et al.2 2018); the second focused on the age-dependent distribution of clinical attachment loss in two population-representative, cross-sectional studies (Billings et al.3 2018); the third reviewed progression data of clinical attachment loss from existing prospective, longitudinal studies (Needleman at al.4 2018); the fourth reviewed the diagnosis, pathobiology, and clinical presentation of acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses, necrotizing periodontal diseases and endo-periodontal lesions; Herrera et al.5 2018); lastly, the fifth focused on periodontitis case definitions (Tonetti et al.6 2018), Table 1.

-

The conflicting literature findings on aggressive periodontitis are primarily due to the fact that (i) the currently adopted classification is too broad, (ii) the disease has not been studied from its inception, and (iii) there is paucity of longitudinal studies including multiple time points and different populations. The position paper argued that a more restrictive definition might be better suited to take advantage of modern methodologies to enhance knowledge on the diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management of this form of periodontitis.

-

Despite substantial differences in the overall severity of attachment loss between the two population samples analyzed by Billings et al.3, suggesting presence of cohort effects, common patterns of CAL were identified across different ages, along with consistencies in the relative contribution of recession and pocket depth to CAL. The findings suggest that it is feasible to introduce empirical evidence-driven thresholds of attachment loss that signify disproportionate severity of periodontitis with respect to age.

-

Longitudinal mean annual attachment level change was found to vary considerably both within and between populations. Surprisingly, neither age nor sex had any discernible effects on CAL change, but geographic location was associated with differences. Overall, the position paper argued that the existing evidence neither supports nor refutes the differentiation between forms of periodontal diseases based upon progression of attachment level change.

-

Necrotizing periodontal diseases are characterized by three typical clinical features (papilla necrosis, bleeding, and pain) and are associated with host immune response impairments, which should be considered in the classification of these conditions (Table 2).

Endodontic-periodontal lesions are defined by a pathological communication between the pulpal and periodontal tissues at a given tooth, occur in either an acute or a chronic form, and should be classified according to signs and symptoms that have direct impact on their prognosis and treatment (i.e., presence or absence of fractures and perforations, and presence or absence of periodontitis) (Table 3).

Periodontal abscesses most frequently occur in pre-existing periodontal pockets and should be classified according to their etiology. They are characterized by localized accumulation of pus within the gingival wall of the periodontal pocket/sulcus, cause rapid tissue destruction which may compromise tooth prognosis, and are associated with risk for systemic dissemination (Table 4).

-

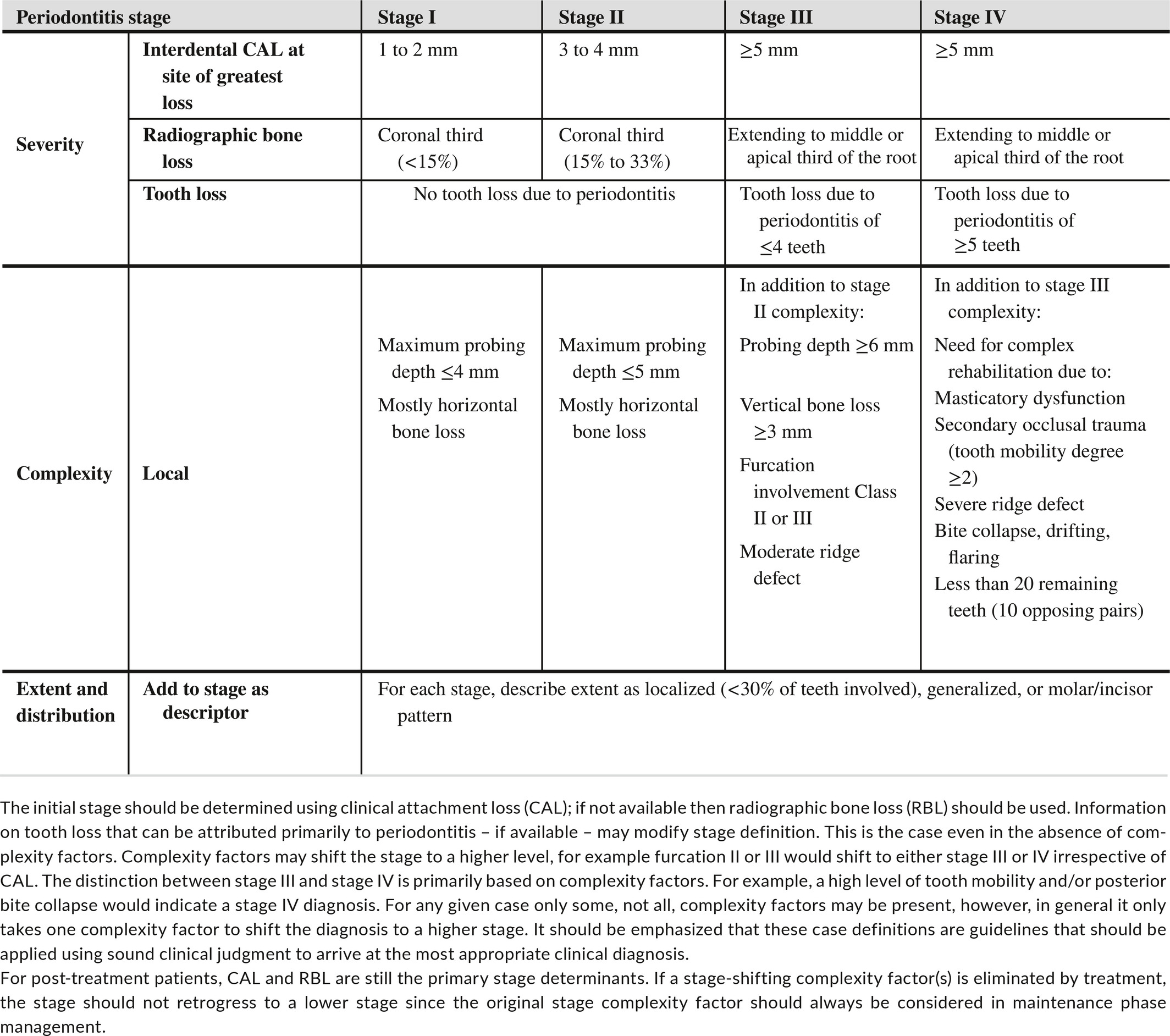

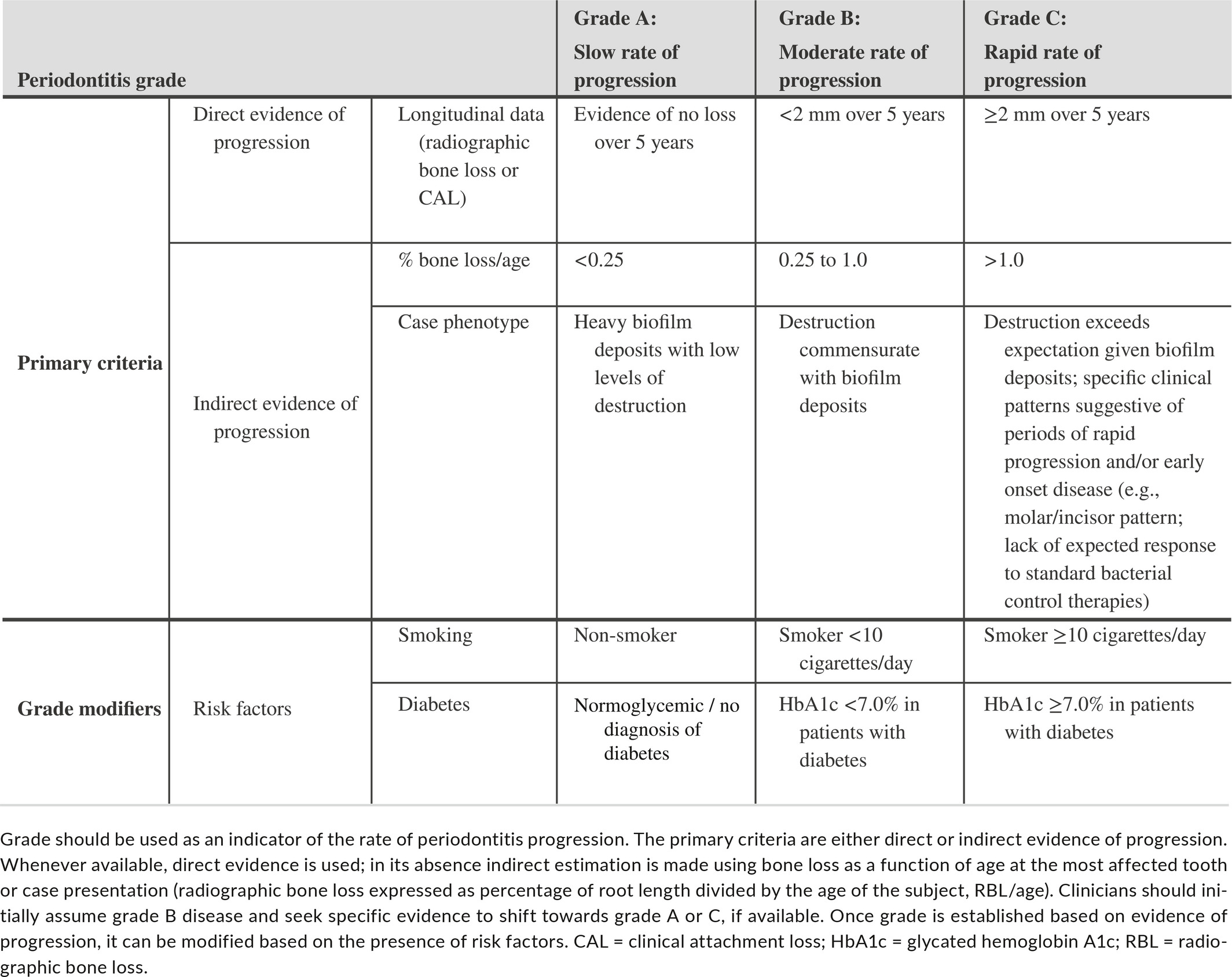

A periodontitis case definition system should include three components: (a) identification of a patient as a periodontitis case, (b) identification of the specific type of periodontitis, and (c) description of the clinical presentation and other elements that affect clinical management, prognosis, and potentially broader influences on both oral and systemic health. A framework for developing a multi-dimensional periodontitis staging and grading system was proposed, in which staging (Table 1) is largely dependent upon the severity of disease at presentation as well as on the complexity of disease management, while grading (Table 2) provides supplemental information about biological features of the disease including a history-based analysis of the rate of periodontitis progression; assessment of the risk for further progression; analysis of possible poor outcomes of treatment; and assessment of the risk that the disease or its treatment may negatively affect the general health of the patient.

During the workgroup deliberations, the following questions were formulated and addressed in order to clarify and substantiate the need for a new classification system for periodontitis:

Which are the main features that identify periodontitis?

Loss of periodontal tissue support due to inflammation is the primary feature of periodontitis. A threshold of interproximal, CAL of ≥2 mm or ≥3 mm at ≥2 non-adjacent teeth is commonly used. Clinicians typically confirm presence of interproximal tissue loss through radiographic assessments of bone loss. Clinically meaningful descriptions of periodontitis should include the proportion of sites that bleed on probing, and the number and proportion of teeth with probing depth over certain thresholds (commonly ≥4 mm and ≥6 mm) and of teeth with CAL of ≥3 mm and ≥5 mm (Holtfreter et al.7).

Which criteria would need to be fulfilled to support the contention that chronic and aggressive periodontitis are indeed different diseases? (e.g., etiology, histology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, other)

Differences in etiology and pathophysiology are required to indicate presence of distinct periodontitis entities; variations in clinical presentation per se, i.e. extent and severity, do not support the concept of different diseases.

Does current evidence suggest that we should continue to differentiate between “aggressive” and “chronic” periodontitis as two different diseases?

Current evidence does not support the distinction between chronic and aggressive periodontitis, as defined by the 1999 Classification Workshop, as two separate diseases; however, a substantial variation in clinical presentation exists with respect to extent and severity throughout the age spectrum, suggesting that there are population subsets with distinct disease trajectories due to differences in exposure and/or susceptibility.

Is there evidence suggesting that early-onset forms of periodontitis (currently classified under “aggressive periodontitis”) have a distinct pathophysiology (e.g., genetic background, microbiology, host-response) compared to later-onset forms?

Although localized early onset periodontitis has a distinct, well-recognized clinical presentation (early onset, molar/incisor distribution, progression of attachment loss), the specific etiologic or pathological elements that account for this distinct presentation are insufficiently defined. Likewise, mechanisms accounting for the development of generalized periodontitis in young individuals are poorly understood.

What are the determinants for the mean annual attachment loss based on existing longitudinal studies in adults?

A meta-analysis included in the position paper documented differences in mean annual attachment loss between studies originating from different geographic regions but did not reveal an association with age or sex. It should be emphasized that meta-analysis of mean data may fail to identify associations due to the loss of information and the lack of accounting for both disease progression and regression. However, approaches that have modelled both progression and regression of CAL have also reported no effect of age or smoking on progression, although age and smoking reduced disease regression (e.g., Faddy et al.8). Individual studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis have shown effects of smoking, socioeconomic status, previous attachment loss, ethnicity, age, sex, and calculus on mean annual attachment loss.

How do we define a patient as a periodontitis case?

-

Interdental CAL is detectable at ≥2 non-adjacent teeth, or

-

Buccal or oral CAL ≥3 mm with pocketing ≥3 mm is detectable at ≥2 teeth but the observed CAL cannot be ascribed to non-periodontitis-related causes such as: 1) gingival recession of traumatic origin; 2) dental caries extending in the cervical area of the tooth; 3) the presence of CAL on the distal aspect of a second molar and associated with malposition or extraction of a third molar, 4) an endodontic lesion draining through the marginal periodontium; and 5) the occurrence of a vertical root fracture.

Which different forms of periodontitis are recognized in the present revised classification system?

-

Necrotizing periodontitis

-

Periodontitis as a direct manifestation of systemic diseases

-

Periodontitis

Differential diagnosis is based on history and the specific signs and symptoms of necrotizing periodontitis, or the presence or absence of an uncommon systemic disease that alters the host immune response. Periodontitis as a direct manifestation of systemic disease (Albandar et al.9, Jepsen et al.10) should follow the classification of the primary disease according to the respective International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) codes.

The remaining clinical cases of periodontitis which do not have the local characteristics of necrotizing periodontitis or the systemic characteristics of a rare immune disorder with a secondary manifestation of periodontitis should be diagnosed as “periodontitis” and be further characterized using a staging and grading system that describes clinical presentation as well as other elements that affect clinical management, prognosis, and potentially broader influences on both oral and systemic health.

How is a periodontitis case further characterized by stage and grade?

An individual case of periodontitis should be further characterized using a simple matrix that describes the stage and grade of the disease. Stage is largely dependent upon the severity of disease at presentation, as well as on the anticipated complexity of disease management, and further includes a description of extent and distribution of the disease in the dentition. Grade provides supplemental information about biological features of the disease including a history-based analysis of the rate of periodontitis progression; assessment of the risk for further progression; analysis of possible poor outcomes of treatment; and assessment of the risk that the disease or its treatment may negatively affect the general health of the patient. For a complete description of the rationale, determinants, and practical implementation of the staging and grading system, refer to Tonetti et al.6 Tables 1 and 2 list the framework of the staging and grading system.

Do the acute periodontal lesions have distinct features when compared with other forms of periodontitis?

Periodontal abscesses, lesions from necrotizing periodontal diseases and acute presentations of endo-periodontal lesions, share the following features that differentiate them from periodontitis lesions: (1) rapid-onset, (2) rapid destruction of periodontal tissues, underscoring the importance of prompt treatment, and (3) pain or discomfort, prompting patients to seek urgent care.

Do periodontal abscesses have a distinct pathophysiology when compared to other periodontitis lesions?

The first step in the development of a periodontal abscess is bacterial invasion or foreign body impaction in the soft tissues surrounding the periodontal pocket, which develops into an inflammatory process that attracts polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and low numbers of other immune cells. If the neutrophil-mediated defense process fails to control the local bacterial invasion or clear the foreign body, degranulation, necrosis and further neutrophilic influx may occur, leading to the formation of pus which, if not drained, results in an abscess. Pathophysiologically, this lesion differs in that the low pH within an abscess leads to rapid enzymatic disruption of the surrounding connective tissues and, in contrast to a chronic inflammatory lesion, has a greater potential for resolution if quickly managed.

What is the case definition of a periodontal abscess?

Periodontal abscess is a localized accumulation of pus located within the gingival wall of the periodontal pocket/sulcus, resulting in a significant tissue breakdown. The primary detectable signs/symptoms associated with a periodontal abscess may involve ovoid elevation in the gingiva along the lateral part of the root and bleeding on probing. Other signs/symptoms that may also be observed include pain, suppuration on probing, deep periodontal pocket, and increased tooth mobility.

A periodontal abscess may develop in a pre-existing periodontal pocket, e.g., in patients with untreated periodontitis, under supportive therapy or after scaling and root planing or systemic antimicrobial therapy. A periodontal abscess occurring at a previously periodontally healthy site is commonly associated with a history of impaction or harmful habits.

Do necrotizing periodontal diseases have a distinct pathophysiology when compared to other periodontitis lesions?

Yes. Necrotizing gingivitis lesions are characterized by the presence of ulcers within the stratified squamous epithelium and the superficial layer of the gingival connective tissue, surrounded by a non-specific acute inflammatory infiltrate. Four zones have been described: (1) superficial bacterial zone, (2) neutrophil-rich zone, (3) necrotic zone and (4) a spirochetal/bacterial infiltration zone.

Necrotizing periodontal diseases are strongly associated with impairment of the host immune system, as follows: (1) in chronically, severely compromised patients (e.g., AIDS patients, children suffering from severe malnourishment, extreme living conditions, or severe infections) and may constitute a severe or even life-threating condition; and (2) in temporarily and/or moderately compromised patients (e.g., in smokers or psycho-socially stressed adult patients).

What are the case definitions of necrotizing periodontal diseases?

Necrotizing gingivitis is an acute inflammatory process of the gingival tissues characterized by presence of necrosis/ulcer of the interdental papillae, gingival bleeding, and pain. Other signs/symptoms associated with this condition may include halitosis, pseudomembranes, regional lymphadenopathy, fever, and sialorrhea (in children).

Necrotizing periodontitis is an inflammatory process of the periodontium characterized by presence of necrosis/ulcer of the interdental papillae, gingival bleeding, halitosis, pain, and rapid bone loss. Other signs/symptoms associated with this condition may include pseudomembrane formation, lymphadenopathy, and fever.

Necrotizing stomatitis is a severe inflammatory condition of the periodontium and the oral cavity in which soft tissue necrosis extends beyond the gingiva and bone denudation may occur through the alveolar mucosa, with larger areas of osteitis and formation of bone sequestrum. It typically occurs in severely systemically compromised patients. Atypical cases have also been reported, in which necrotizing stomatitis may develop without prior appearance of necrotizing gingivitis/periodontitis lesions.

Do endo-periodontal lesions have a distinct pathophysiology when compared to other periodontitis or endodontic lesions?

The term endo-periodontal lesion describes a pathologic communication between the pulpal and periodontal tissues at a given tooth that may be triggered by a carious or traumatic lesion that affects the pulp and, secondarily, affects the periodontium; by periodontal destruction that secondarily affects the root canal; or by concomitant presence of both pathologies. The review did not identify evidence for a distinct pathophysiology between an endo-periodontal and a periodontal lesion. Nonetheless, the communication between the pulp/root canal system and the periodontium complicates the management of the involved tooth.

What is the case definition of an endo-periodontal lesion?

Endo-periodontal lesion is a pathologic communication between the pulpal and periodontal tissues at a given tooth that may occur in an acute or a chronic form. The primary signs associated with this lesion are deep periodontal pockets extending to the root apex and/or negative/altered response to pulp vitality tests. Other signs/symptoms may include radiographic evidence of bone loss in the apical or furcation region, spontaneous pain or pain on palpation/percussion, purulent exudate/suppuration, tooth mobility, sinus tract/fistula, and crown and/or gingival color alterations. Signs observed in endo-periodontal lesions associated with traumatic and/or iatrogenic factors may include root perforation, fracture/cracking, or external root resorption. These conditions drastically impair the prognosis of the involved tooth.

Which are the current key gaps in knowledge that would inform a better classification of periodontitis and should be addressed in future research?

-

Develop improved methodologies to assess more accurately the longitudinal soft and hard tissue changes associated with periodontitis progression

-

Identify genetic, microbial, and host response-associated markers that differentiate between distinct periodontitis phenotypes, or which can reflect the initiation and progression of periodontitis.

-

Expand existing epidemiological databases to include world regions currently underrepresented, utilizing consistent, standardized methodologies, and capturing and reporting detailed data on both patient-related, oral, and periodontal variables. Open access to the detailed data is crucial to facilitate comprehensive analyses.

-

Integrate multi-dimensional data platforms (clinical, radiographic, -omics) to facilitate systems biology approaches to the study of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions

-

Use existing databases/ develop new databases that will facilitate the implementation, validation and continuous refinement of the newly introduced periodontitis classification system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

Workshop participants filed detailed disclosure of potential conflicts of interest relevant to the workshop topics, and these are kept on file. The authors receive, or have received, research funding, consultant fees, and/or lecture compensation from the following companies: 3M, Amgen, CardioForecast, Colgate, Dentaid, Dentium, Dentsply Sirona, Dexcel Pharma, EMS Dental, GABA, Geistlich, GlaxoSmithKline, Hu-Friedy, IBSA Institut Biochimique, Interleukin Genetics, Izun Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, Klockner, Menarini Ricerche, MIS Implants, Neoss, Nobel Biocare, Noveome Biotherapeutics, OraPharma, Osteology Foundation, Oxtex, Philips, Procter & Gamble, Sanofi-Aventis, Straumann, SUNSTAR, Sweden & Martina, Thommen Medical, and Zimmer Biomet.

REFERENCES