Management of primary aldosteronism in patients with adrenal hemorrhage following adrenal vein sampling: A brief review with illustrative cases

Funding information

Funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (project number Z1A HD008920)

Abstract

The authors describe the clinical investigation of two cases of primary aldosteronism with adrenal hemorrhage (AH) following adrenal vein sampling. A literature review was conducted regarding the medical management of primary aldosteronism in patients with AH following adrenal vein sampling. Guidelines on the management of primary aldosteronism with AH following adrenal vein sampling are lacking. The two patients were followed with serial imaging to document resolution of AH and treated medically with excellent blood pressure response. Resolution of AH was achieved, but a repeat adrenal vein sampling was deferred given the increased morbidity risk associated with a repeat procedure.

1 INTRODUCTION

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is the most common cause of endocrine hypertension with a prevalence rate of 5% to 15% in the hypertensive population. Early recognition and treatment is critical to decrease the cardiometabolic and cerebrovascular complications associated with PA. The major causes of PA are bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia and aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA).1 Adrenal vein sampling (AVS), first introduced in 1967, has become the gold-standard procedure for differentiating between bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia and APA.2 However, AVS is invasive and technically challenging, with only a few centers in the United States able to perform this procedure.3 In specialized centers, AVS is performed successfully over 97% of the time.3-5 Exceptions to AVS in the evaluation of PA include a patient's preference to seek medical treatment only, or for young patients (younger than 35 years) with undetectable plasma renin, plasma aldosterone concentration >20 ng/dL, profound hypokalemia, and a unilateral adenoma on imaging.1

Complication rates of AVS are minimal, varying from 0.2% to 10%.2, 4-6 Because the right adrenal vein drainage is more complex and difficult to cannulate, complications occur more often on this side.3-7 An uncommon but potentially serious complication of AVS is adrenal hemorrhage (AH), which can arise secondary to transection, or less commonly infarction, thrombosis, or dissection of the adrenal vein.3 The rates of AH have significantly improved as a result of the standard use of computed tomography (CT) to better characterize the adrenal glands and their vessels, lower amounts of contrast use during AVS, and increasing experience of interventional radiologists as PA is being more frequently recognized.3, 7 Nonetheless, complications from AVS are associated with prolonged hospitalization, administration of pain medications, exposure to radiation from repeated imaging, and, rarely, an emergent laparotomy.

The next steps in the evaluation and treatment of PA following AH are not straightforward. Should a repeat AVS be attempted if the initial AVS results were nondiagnostic? If so, after what time period? What is the risk of postoperative adrenal insufficiency if the AH is contralateral to the APA? Herein, we describe two patients who experienced AH following AVS, with a review of the related literature.

2 CASE 1

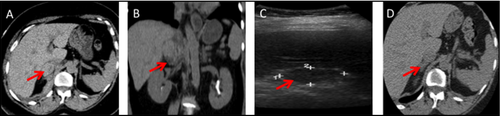

A 56-year-old black woman presented for evaluation of resistant hypertension since the age of 21 years. Her hypertension was poorly controlled on four antihypertensive medications. A stepwise testing approach for PA (Table 1) confirmed the diagnosis. Adrenal CT showed bilateral nodular hyperplasia, most notably in the lateral limb of the left adrenal. She underwent AVS with successful cannulation, with lateralization to the left adrenal gland. Two hours post procedure, she complained of severe right upper quadrant pain radiating to the right shoulder. Examination was significant for rigidity and rebound tenderness in the right upper quadrant. CT scan and ultrasonography findings (Figure 1A-C) of the abdomen showed a right AH. Hematocrit and hemoglobin levels remained within reference range, so the patient was managed conservatively and discharged after 4 days of hospitalization. On repeat serial imaging at 6 months, there was an almost complete resolution of the hemorrhage (Figure 1D). The patient was placed on eplerenone monotherapy and she is currently with excellent blood pressure control.

| Tests | Case 1 | Case 2 | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening tests | |||

| Plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) | 16.5 ng/dL | 32.4 ng/dL | 1–21 ng/dL |

| Plasma renin activity (PRA) | ≤0.6 ng/mL/h | ≤0.6 ng/mL/h | ≤0.6–3 ng/mL/h |

| PAC/PRA | ≥27.5 | ≥54 | <20 |

| Confirmatory tests | |||

| 24-h urine sodium secretion | 251 mmol/24 h | 130 mmol/24 h | 40–220 nmmol/24 h |

| 24-h urine aldosterone | 21 μg/24 h | 62 μg/24 h | <12 μg/24 h |

| Saline suppression test | |||

| Aldosterone | |||

| Baseline | 16 ng/dL | 44.5 ng/dL | |

| 1 h | 12 ng/dL | 39.5 ng/dL | |

| 2 h | 12 ng/dL | 36.1 ng/dL | |

| 3 h | 5.9 ng/dL | 39.9 ng/dL | |

| 4 h | 7.6 ng/dL | 31.5 ng/dL | |

3 CASE 2

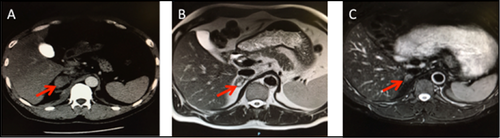

A 46-year-old white man with poorly controlled hypertension and hypokalemia since the age of 35 years was evaluated for PA. A stepwise testing approach for PA (Table 1) confirmed the diagnosis. Adrenal CT showed a 4.5-mm left adrenocortical nodule. The patient underwent his first AVS at an outside institution, without major complications, but because he was taking eplerenone at the time, the results were uninterpretable. A repeat AVS off eplerenone performed at the same institution failed to cannulate the right adrenal vein. Three hours after the procedure, he complained of sudden-onset diffuse abdominal pain with rigidity and vomiting. Serial abdominal imaging confirmed a stable right adrenal hematoma that was managed conservatively (Figure 2A,B). Repeat serial imaging showed near resolution of the hematoma (Figure 2C). We deferred performing a third AVS in this patient, and he remains on eplerenone therapy with excellent blood pressure control to date.

4 MANAGEMENT OF PA POST AH

Management of PA post AH involves shared decision-making with the patient. Although a previous AH does not necessarily exclude the possibility of a repeat AVS, physicians should approach such scenarios on a case-by-case basis, and in specialized referral centers with sufficient throughput and expertise.1, 3 The risk of AH from AVS is largely caused by adrenal vein anatomy and sampling requirements. In initially searching for the adrenal veins, contrast injection is required for finding suitable candidates. Once a candidate vein has been identified, the catheter, which should ideally remain in position throughout AVS, is used for sampling. If the catheter dislodges as a result of respiratory movements, repeat positioning and blood redraws with postsampling verification injections are required. In the event of catheter dislodgement, readjustment and repeat sampling with additional contrast injections are required, all of which raise the risk for AH.

The left adrenal vein is less likely to result in AH during AVS for several reasons. It is easier to cannulate because it is frequently better visualized on preprocedural CT imaging, longer, and anatomically more constant in location, draining into the left renal vein.5, 8 The left vein is also more tolerant of forceful injections of contrast, a potential cause of AH.5 In addition, the left AVS catheter does not have to be checked as often as the right since less frequent dislodgement is observed, particularly with respiratory motion. An experienced interventional radiologist would only need to check the left adrenal vein catheter approximately three times during the procedure: at the beginning, middle, and end of AVS.

Conversely, the right adrenal gland is more commonly affected by complications from AVS given its more complex venous anatomy. The right adrenal vein is shorter and drains directly into the inferior vena cava, often at an acute angle, making it difficult to cannulate and often requiring multiple attempts.7-9 In addition, the right venous drainage anatomy can be variable, with an isolated adrenal vein, renal capsular accessory vein, or hepatic accessory vein representing the dominant vessel.5 The shorter right-sided adrenal veins enable respiratory movements to dislodge the catheter more easily, requiring multiple right AVS catheter placement checks (ie, before and after every sample attempt to ensure that the catheter is within the vein). Thus, to avoid AH, AVS must be ideally performed at specialized centers. Moreover, a dedicated adrenal CT scan with contrast before AVS is strongly recommended to enable accurate adrenal vein mapping.

The major complications of AVS include adrenal vein rupture, dissection, infarction, and thrombosis that leads to intraglandular and periadrenal hematoma.3, 5 AH is clinically characterized by a persistent and progressive abdominal pain with rigidity during or after catheterization, requiring pain control. The diagnosis is confirmed by noncontrast CT, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasonography, with careful serial monitoring of vital signs and abdominal examination. Sequential imaging is necessary to document stability of the AH. Complications usually resolve with conservative treatment although an enlarging hematoma with or without clinical stability may warrant an emergency laparotomy. Subsequent laparoscopic adrenalectomy could be more difficult because of extensive retroperitoneal adhesions, while repeat AVS could be challenging given the anatomic changes, particularly in the adrenal vasculature.

The AVIS (AVS International Study)10 was an observational, retrospective, multicenter study that examined the risks in 2604 AVS procedures over a 6-year period and found a rate of adrenal vein rupture in 0.61%. The investigators also found that AH was inversely correlated with the number of procedures performed by each radiologist.10 In another study that primarily explored the management and outcomes of AH during AVS, Monticone and colleagues11 reported 24 cases of PA with AH from six different centers. AH occurred more frequently (n=18 of 24) in the right adrenal vein, in keeping with previously published reports.3, 6, 10 The most common symptom of AH was abdominal pain that required treatment with a strong opioid therapy, and hospital stay was prolonged on average by 1.9±1.3 days. In the majority of patients, bilateral adrenal function was preserved. Collectively, AH following AVS appears to have a benign course and does not affect adrenal function in the majority of cases.

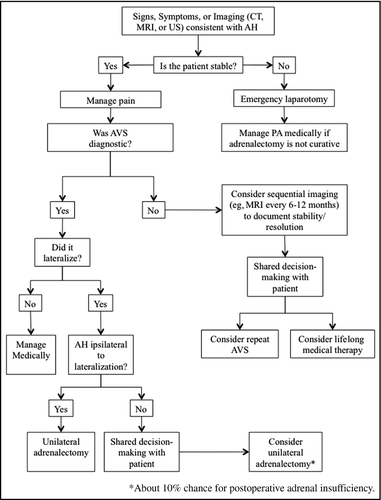

Several clinical decision questions and scenarios may arise in the management of AH following AVS (Figure 3). For example, if the AVS was terminated early as a result of the AH, or was nondiagnostic, it is unclear whether to repeat AVS testing, treat with lifelong medical therapy, or, in the case of a suspected APA, to simply proceed to unilateral adrenalectomy. Because AH rarely obliterates the entire gland, it often has no effect on blood pressure control or biochemical levels, even if ipsilateral to the culprit APA.11, 12 Therefore, the lack of a “blood pressure response” after AH gives no discriminatory information regarding the laterality of the disease. In the study by Monticone and colleagues,11 two patients with AH with nondiagnostic AVS results had repeat AVS successfully performed without complications.11 However, because repeat AVS testing after AH is rarely described in the literature, the risk of complications and repeat nondiagnostic results or the optimal timing on when to perform the repeat procedure is entirely unclear. Conversely, because bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia with nodularity can mimic APA on imaging, proceeding to a “blind” unilateral adrenalectomy based on CT imaging without AVS data may result in the erroneous gland being removed.13 Adrenal-sparing nodulectomy to save part of the functioning cortex surrounding the APA could be considered instead, but because ≈15% of APAs may have concurrent cortical hyperplasia, this surgical strategy may lead to a clinically ineffective outcome.14 A superselective segmental adrenal vein branches AVS may be considered, but this is a highly demanding procedure, which is performed in a few select centers.15

In instances where AVS lateralization data are successfully acquired, if the AH affects the contralateral adrenal to an APA, one may question whether surgically removing the adrenal with the APA will render the patient adrenally insufficient (Figure 3). As demonstrated by Monticone and colleagues,11 only one case of adrenal insufficiency was encountered in such a scenario, suggesting that this is a rare occurrence. However, because of the limited sample size, one cannot make definitive conclusions. Conversely, if AH occurred ipsilateral to the APA, then a unilateral adrenalectomy should still be planned, except in the unlikely event that the AH cured the hyperaldosteronism. In general, if AVS results are consistent with bilateral disease, then there is no need to repeat AVS and the patient should be treated with lifelong mineralocorticoid antagonist therapy in most cases. In case 1, the patient had unilateral disease, and with the resolution of the AH, surgical treatment could have been an option. However, given the possible, albeit low, risk of postoperative adrenal insufficiency, the patient preferred medical therapy. Should the hyperaldosteronism worsen and the patient fail medical therapy at some point in the future, a surgical option could be reviewed again. In case 2, the laterality of disease was unclear, so repeat AVS could be a possible option, but because the risk of complications is unknown (and likely significantly higher than for an initial AVS), medical treatment was pursued.

5 CONCLUSIONS

AVS has been proven to be a reliable procedure for PA subtype diagnosis to direct patients to surgery or medical treatment. Training of dedicated radiologists, and other related healthcare professionals, is crucial for a successful procedure that might improve therapeutic management of PA. Potentially serious complication of AVS, such as AH, might occur and, in that situation, postprocedural abdominal pain should be treated as a medical emergency. Repeat AVS following AH should be performed with caution on a case-by-case basis, and lifelong medical management with a mineralocorticoid antagonist is a reasonable option. As the answers are not straightforward, the patient should be engaged in shared decision-making for the next steps after a careful assessment of the risks and benefits. Future guidelines should address the management of AH following AVS to help guide clinicians in the management of these patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any potential conflicts of interest.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.