Press Freedom and Systemic Risk

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the role of press freedom on systemic risk using an international sample of banks. We construct a novel and comprehensive measure of press freedom by integrating data from multiple widely recognized sources: the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom country ranking, the Freedom of Expression Index, and the Freedom House Index. By combining these three distinct indices, our measure offers a more robust and multi-dimensional assessment of press freedom, capturing a broader spectrum of factors influencing media independence and freedom of expression across countries. Our empirical evidence suggests that press freedom is associated with lower systemic risk in the banking sector. We show that this relationship is mitigated during the upward phase of the economic cycle, and enhanced during banking crises. Our findings hold when addressing potential endogeneity problems and when accounting for additional macroeconomic and firm controls.

1 Introduction

Public information plays an important role in the stability of the banking sector. A transparent banking system enables market discipline, but at the same time, public information may lead market participants to overreact to potentially noisy signals, resulting in adverse consequences (Morris and Shin 2002). The press serves as the key agent responsible for conveying information to the public in a truthful and accurate manner, thereby helping to reduce information asymmetries in financial markets (Kim et al. 2014). It is often cited as the public's watchdog, at national, regional, and local levels, preventing misinformation among citizens. However, according to the Reporters Without Borders (henceforth referred to as RSF, from the French “Reporters sans frontières”), currently, only 48 out of 180 countries have a good or satisfactory level of press freedom, suggesting that, in many cases, journalists’ work is being compromised. This may be driven by different interested entities such as the local government that may seek to influence political outcomes by controlling the media (Besley and Prat 2006). Considering the important role of the press for the financial sector, we examine the relationship between press freedom and systemic risk.

Press freedom is at the core of a democratic society. The absence of censorship encourages journalists to investigate and uncover stories on corruption and wrongdoing; therefore, they have a role as information intermediaries and corporate monitors (T. Nguyen 2021). Since the media can alleviate informational frictions, they affect investors’ sentiment and perspective influencing securities’ financial performance. Bad news or media pessimism can be seen by investors as a proxy for new information and consequently lead to market corrections (Tetlock 2007; Wisniewski and Lambe 2013; Carlini et al. 2020). The impact of media news reporting is significant, even in cases of fake news, while stocks with high media coverage perform worse than those with no coverage (Fang and Peress 2009). The literature also documents that media coverage is associated with positive firm outcomes such as higher productivity (Khalifa, Sheikhbahaei, and Sualihu 2024), greater green innovation (Gao et al., Early View), and better controlled opportunistic earnings management behaviors (Chen et al. 2021).

However, the role of public information in enhancing market discipline within the banking sector is debated by financial economists. On the one hand, greater transparency can enhance the informativeness and efficiency of the financial markets (e.g., Livingston, Wei, and Zhou 2010; Sato 2014; Blau, Brough, and Griffith 2017; Jia et al. 2023). Moreover, the lack of transparency can increase risk-taking (Fosu et al. 2017; Cao and Juelsrud 2022) and impede lending growth (Zheng 2020). On the other hand, others argue that public information may not always be beneficial for bank stability. By keeping important information private, banks can maintain their charter value and operate more efficiently (Berger et al. 2000; T. V. Dang et al. 2017). Additionally, if outsiders cannot easily observe the condition of the bank, the risk of a run is reduced (Jungherr 2018). Huang and Ratnovski (2011) argue that this is more prevalent with wholesale financiers who may use public signals instead of conducting costly monitoring to withdraw their funding, while Becchetti and Manfredonia (2022) find that negative media attention increases bank loan costs. Our study contributes to this ongoing debate and seeks to enhance our understanding of the role of public information for the banking sector.

In this paper, we examine the relationship between press freedom and systemic risk, as well as the role that economic growth and banking crises play in this relationship. Our study utilizes an international sample of 259 banks from 47 countries during the period of 2006–2022. We construct a novel and comprehensive measure of press freedom by integrating data from multiple widely recognized sources: the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom country ranking, the Freedom of Expression Index, and the Freedom House Index. Systemic risk is measured using ΔCoVaR and the Marginal Expected Shortfall (MES), which are widely employed metrics in the literature. We find that press freedom and systemic risk exhibit a negative relationship. However, we also document that economic growth and banking crises play an important role in this relationship. We address endogeneity concerns using the two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimator. To instrument press freedom, we use the level of academic freedom as well as the level of democracy in the bank's host country. We expect that both variables are positively correlated with press freedom, which satisfies the relevance criterion, and that they are unrelated to bank systemic risk to satisfy the exclusion restriction.

Our paper makes several unique contributions to the literature. First, we contribute to the limited strand of the literature that examines the importance of press freedom. Only a few studies dedicate attention to this important parameter for society, and even fewer have examined its connection with the financial markets and the banking system. Second, we add empirical evidence to the determinants of systemic risk, contributing not only to the understanding of systemic risk but also to the broader literature on bank stability and risk-taking. This is a traditional strand of the literature that has gained more attention after the shortcomings in the sector during the global financial crisis of 2007–2009. In particular, previous literature has focused on systemic risk determinants such as firm characteristics (Varotto and Zhao 2018; Dungey et al. 2022), asset price bubbles (Brunnermeier, Rother, and Schnabel 2020), market competition (Anginer, Demirguc-Kunt, and Zhu 2014), external factors, such as credit rating downgrades (Kladakis And Skouralis, forthcoming), and the macroeconomic environment (Giglio, Kelly, and Pruitt 2016). Third, we extend our understanding of the mechanisms of press freedom by incorporating economic growth and banking crises as two key moderating factors. The interplay of economic growth and banking crises with systemic risk is of outmost importance, given that regulators’ primary objective in limiting systemic risk is to prevent adverse consequences in the real economy. Finally, we also contribute to the measurement of press freedom. By combining three distinct indices from reliable sources, our new measure offers a more robust and multi-dimensional assessment of press freedom, capturing a broader spectrum of factors influencing media independence and freedom of expression across countries. We believe that a more comprehensive measure is needed to account for the varying methodologies and focus areas of existing indices, which individually may overlook important dimensions of press freedom or provide inconsistent evaluations across countries.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the theoretical framework and hypotheses development; Section 3 describes the data, main variables, and empirical framework; Section 4 discusses our baseline empirical results; Section 5 presents our robustness tests; and Section 6 concludes and discusses the policy implications of our study.

2 Related Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1 Press Freedom and Systemic Risk

We posit that the level of press freedom in a country may be negatively associated with bank systemic risk due to a combination of different underlying mechanisms.1 First, the media impose pressure on firms’ managers and board of directors as the literature provides numerous examples of how the press affects corporate governance. For instance, Dyck, Morse, and Zingales (2010) study all reported fraud cases in the United States in the period of 1996–2004, and they argue that media pressure can be one of the most effective mechanisms for detecting corporate fraud. At the same time, Miller (2006) finds that the media act as a “watchdog” for accounting fraud by rebroadcasting information from other analysts and auditors.

Journalists often focus on cases of corporate wrongdoing because a big story can boost their career development and reputation (You, Zhang, and Zhang 2018). These stories usually focus on excess compensation (Core, Guay, and Larcker 2008; Kuhnen and Niessen 2012) and socially unacceptable actions and policies (Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales 2008). Media critique on board ineffectiveness forces shareholders to take corrective actions (Joe, Louis, and Robinson 2009) as managers realize that their career development depends on the media coverage that their company receives. Jia et al. (2023) find that borrowers’ media coverage affects their lenders’ decisions. In line with this, El Ghoul et al. (2019) find that firms engage in more CSR activities if they are based in countries with greater media freedom. Consequently, press freedom can shape firms’ corporate governance, which plays an important role in bank risk-taking (Laeven and Levine 2009; Srivastav and Hagendorff 2016).

Second, press freedom can reduce information asymmetries and improve transparency in financial markets (T. L. Dang et al. 2020). In countries with less developed financial systems and firms characterized by poor corporate governance, managers may hoard information within the firm and control the flow of information to the public. Therefore, the lack of transparency can result in higher stock price synchronicity by shifting firm-specific risk to managers (Jin and Myers 2006). Kim, Li, and Zhang (2011) find that managers hide bad news and benefit financially by using tax shelters to increase earnings at the expense of shareholders, potentially leading to a higher probability of a stock price crash. In addition, opaque firms with no media coverage and a high degree of synchronicity are more likely to experience distress (Hutton, Marcus, and Tehranian 2009),2 while banks with negative media attention experience lower stock returns (Wisniewski and Lambe 2013; Carlini et al. 2020). Kim et al. (2014) use press freedom as a measure of transparency and find that it is associated with more informative stock prices and lower price synchronicity. More recently, Berlinger et al. (2022) show that press freedom has a positive association with the frequency and severity of observed corporate operational losses and that in countries with controlled media hidden operational risks are significantly higher. Therefore, close monitoring of banks by the media can potentially mitigate managerial bad-news hoarding, reduce both stock price synchronicity, and crash risk (An and Zhang 2013) and thus limit banks’ systemic risk.

Third, press freedom can reveal fundamental cultural differences across countries. More specifically, press freedom is negatively correlated with country-level corruption, as an independent press may serve as an important safeguard against fraud and illegal activities (Brunetti and Weder 2003). Eun, Wang, and Xiao (2015) find that culture plays a significant role in trading activities and information sharing, directly affecting financial markets’ performance.3 The negative effects of corruption on banks are well-documented in the literature. Various studies find that corruption can contribute to higher lending rates (Pagano 2008), increase the share of bad loans (Park 2012) and impede overall bank stability (Asteriou, Pilbeam, and Tomuleasa 2021). De Jonghe, Diepstraten, and Schepens (2015) show that the benefits of non-interest income for systemic risk disappear in countries with high levels of corruption. Poor levels of press freedom can contribute to a corrupt environment for banks, harm bank stability, and increase systemic risk.

Due to the aforementioned mechanisms related to corporate governance, information asymmetries, and corruption, we anticipate a negative relationship between press freedom and systemic risk and formulate our Hypothesis 1 as follows:

H 1.Press freedom is negatively associated with bank systemic risk.

2.2 The Moderating Role of Economic Growth and Banking Crises

The study of systemic risk is at the center of policymakers’ attention because exposure to systemic risk can lead to real macroeconomic declines and crises (De Bandt and Hartmann 2002; Kambhu, Schuermann, and Stiroh 2007; Allen, Bali, and Tang 2012; Giglio, Kelly, and Pruitt 2016). Especially when a large number of banks are distressed and begin reducing the provision of credit, the adverse consequences to the real economy are almost inevitable. Yet, when the economy is expanding, real economic growth can contribute to the build-up of systemic risk. Economic expansion is usually associated with strong credit increases, substantial consumption growth, increased market participation, and higher capital accumulation as well as employment growth. Systemic risk can silently grow during an expansionary period but only materialize during a subsequent downturn (Borio and Lowe 2002). At the same time, significant increases in systemic risk have been documented during periods of crisis. Fire sales, contagion of risk, heightened correlations, liquidity constraints, and interconnectedness are some of the factors that contribute to increased uncertainty and explosive growth of systemic risk during crises. But in which of the two periods press freedom can be more effective in controlling systemic risk?

One the one hand, during economic growth, press freedom may be more useful in mitigating systemic risk. As the economy grows, free media can support the transparent flow of information and assist the public in making prudent financial decisions. Vigilant and independent media can highlight potential pitfalls, dubious financial practices, or signs of an overheating economy, enabling the public to exercise caution in their financial endeavors. As banks significantly expand their provision of credit, a well-informed public can make good investment and spending decisions that will limit the build-up of systemic risk. As a result, we can argue that during economic growth, press freedom can support the population in making prudent financial decisions4 thereby limiting bank systemic risk. Following the same reasoning, during periods of banking crises, press freedom is less useful in controlling bank systemic risk.

H 2a.Economic growth enhances the negative relationship between press freedom and systemic risk.

H 3a.The negative relationship between press freedom and systemic risk is weaker during banking crises.

On the other hand, as the economy grows, press freedom may also be less powerful in reducing systemic risk, compared to periods of economic contraction or crises. During economic downturns, the intricacies of financial markets often become more pronounced, leading to heightened uncertainty and a surge in information asymmetries. This phenomenon is extensively documented in the literature (e.g., Yuan 2005; Mishkin 2009; Cerutti et al. 2015). In times of crisis, the financial landscape becomes more complex and volatile, making it challenging for market participants to accurately gauge risks and make informed decisions. This heightened uncertainty can contribute to a lack of transparency and increased information asymmetries, where certain market players possess more information than others. In such a challenging environment, press freedom assumes heightened significance as it can act as a crucial mechanism for mitigating information asymmetries. Additionally, press freedom serves as a check on potentially misleading or manipulative practices that might exacerbate the challenges during economic crises. Investigative journalism and critical analysis become essential tools in uncovering hidden risks, fraudulent activities, or malpractices within the financial system. Successively, by acting as a disseminator of reliable information, the press can help alleviate the heightened uncertainty prevailing in financial markets during crises. This, in turn, empowers investors, businesses, and the general public to make more informed decisions, thereby reducing the severity of systemic risks that may arise from uninformed or panic-driven actions.

H 2b.Economic growth limits the relationship between press freedom and systemic risk.

H 3b.The negative relationship between press freedom and systemic risk is stronger during banking crises.

3 Data, Main Variables, and Empirical Framework

3.1 Data

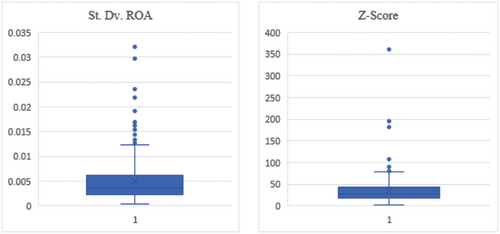

We obtain data from a variety of sources to test our hypotheses using an international sample. First, we employ annual bank-level data from the S&P Capital IQ Pro database. We select all companies classified as banks by the database and with available observations for the variables used in our regressions. Second, we obtain the press freedom country ranking by RSF, the Freedom of Expression Index by V-Dem, the Freedom House index by Freedom House and the killings of journalists from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Third, we collect market data for the estimation of systemic risk by Thomson Reuters EIKON Datastream. Fourth, we use the industrial production data by the OECD and all remaining macroeconomic variables by the World Bank. The resulting common sample used in our analysis consists of 259 banks from 47 countries in the period of 2006–2022.5 To show the level of risk-taking of banks in our sample, Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of ROA volatility and Z-Score for the banks in our sample. The boxplots suggest relatively low levels of risk-taking on average.

3.2 Main Variables

3.2.1 Press Freedom

We use principal components analysis (PCA) to construct a comprehensive measure of press freedom. We employ three key factors that can reflect the level that media can disseminate news in the general public independently from any political or legal interference. First, we use the change in the country ranking provided by RSF to measure the level of press freedom. RSF calculates and publishes the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) aiming to provide a comparable estimate of the level of press freedom across the globe. Each country's score is a combination of five contextual indicators (subsidiary scores) that measure press freedom in terms of political and economic context, legal framework, culture, and safety. After the calculation of the score, countries are ranked based on their WPFI.6 Second, we use the change in the Freedom of Expression Index by V-Dem. This variable reflects the degree to which individuals can engage in discussions about political issues both within their households and in the public domain. It also encompasses the liberty of the press and media to freely present diverse political viewpoints, along with the freedom of expression in academic and cultural contexts. Finally, we use the Freedom House index.7 Freedom House assesses the level of political rights and civil liberties available to individuals in 210 countries and territories through its annual Freedom in the World report. The index measures a variety of personal freedoms, including the right to vote, freedom of expression, and legal equality, all of which can be influenced by both governmental and non-governmental actors. We use the first principal component of these three variables as our measure of press freedom. In Section 5, we present our results using these variables individually.

In addition to the three indices that we incorporate in the PCA, we also use the number of killings of journalists in a given year in a more limited sample. The number of killings of journalists serves as a tragic but telling metric for assessing the state of press freedom. It underscores the importance of creating an environment where journalists can work without fear for their safety, ensuring a vibrant and uninhibited flow of information to the public.

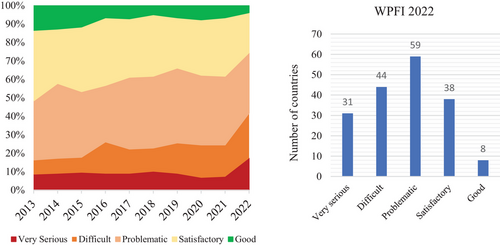

RSF classifies countries into five different groups according to their results. Based on the 2022 data, in 31 countries the WPFI is low, indicating that the country has a “very serious” freedom deficit. In total, 59 countries belong to the “problematic” category followed by 44 countries that belong in the “difficult” classification. From the 180 countries in the 2022 sample, 22% of them have a satisfactory level of press freedom, and only 4% (8 countries) are identified as having a good level of press freedom.

Figure 2 displays on the right-hand side the number of countries per classification for 2022. On the left-hand side, the chart shows the percentage of companies in each classification over the last 10 years. The data suggest that press freedom has deteriorated over the last few years. In 2013 and 2014, 13% of the countries belonged in the upper classification with a “good” degree of press freedom. However, the percentage dropped to 7% for the period 2016–2021 and to 4% in 2022. The group of countries with “satisfactory” media freedom exhibit a similar pattern with its percentage decreasing from 38% in 2013 to 22% in the latest survey. On the other hand, the number of countries in the two classifications with the lower scores increased dramatically from 8% 10 years ago to 24% classified as “difficult” and 17% as “very serious.” Overall, the data indicate the deterioration of press freedom at a global level.

3.2.2 Measuring Systemic Risk

3.3 Empirical Framework

ΔCoVaR is our main measure of systemic risk as described in Section 3.2.2, while PRESS FREEDOM is our main measure of press freedom as described in Section 3.2.1. We use several control variables that are commonly employed in the literature that examines the determinants of systemic risk (e.g., Anginer, Demirguc-Kunt, and Zhu 2014; Brunnermeier, Rother, and Schnabel 2020; Davydov, Vähämaa, and Yasar 2021; Kladakis And Skouralis, forthcoming). VaR stands for value at risk. LNTA is the natural logarithm of the bank's total assets. MB is the market-to-book ratio. EQTA is the ratio of total equity to total assets. LOANS is the ratio of total loans to total assets. GDP is the bank's host country's annual GDP growth.10 COVID (2020–2022) is a dummy variable that equals 1 for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022. Tables 1, 2, and 3 present the definitions, descriptive statistics, and correlation matrix, respectively, for all variables used in our regressions. We do not observe any high levels of correlation among our variables that would indicate multicollinearity problems. Only (NON-)CORRUPTION is highly correlated with PRESS FREEDOM, ARTICLES, and DEMOCRACY, and we carefully use it as an additional control variable in Section 5. Nevertheless, our results hold with and without this variable.

| Variable | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| PRESS FREEDOM | The first principal component of the change in the bank's host country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index and the Freedom House index | Authors’ calculation using below sources |

| ΔRSF | The change in the bank's host country's RSF ranking | Reporters Without Borders (RSF) |

| ΔFEI | The change in the bank's host country's freedom of expression index | V-Dem |

| FREEDOM HOUSE | The bank's host country's freedom house index | Freedom House |

| KILLINGS_INV | The inverse of the number of killings of journalists in the bank's host country | Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) |

| ΔCoVaR | The difference between the Conditional VaR of the financial system when a firm is under distress (5th percentile) and during normal times (50th percentile) | Thomson Reuters EIKON Datastream |

| MES | The mean of the daily returns of the examined banking institution, when the financial sector index is equal or below its VaR, as defined by its historical distribution | Thomson Reuters EIKON Datastream |

| VaR | Value-at-risk (VaR) is defined as the left tail (5th percentile) of the historical daily returns | Thomson Reuters EIKON Datastream |

| LNTA | The natural logarithm of total assets | S&P Capital IQ Pro |

| MB | Market-to-book ratio | S&P Capital IQ Pro |

| EQTA | Total equity/total assets | S&P Capital IQ Pro |

| NONINT | Non-interest income/total revenue | S&P Capital IQ Pro |

| LOANS | Total loans/total assets | S&P Capital IQ Pro |

| ROA | Return on assets. Total income/average total assets | S&P Capital IQ Pro |

| COST-TO-INCOME | Operating costs/operating income | S&P Capital IQ Pro |

| COVID (2020–2022) | Equals 1 if the year is 2020, 2021, or 2022 and 0 otherwise | Authors’ Calculation |

| GDP | Gross domestic product annual growth of the bank's host country | World Bank |

| GDP VARIANCE | The variance of the bank's host country's GDP growth in the previous 5 years | Authors’ Calculation |

| INDPROD | Industrial production annual growth of the bank's host country | OECD |

| CRISIS | Equals 1 if the bank's host country has experienced a banking crisis in the given year | Harvard Business School |

| INFLATION | The annual inflation rate of the bank's host country | World Bank |

| UNEMP | The total unemployment rate of the bank's host country | World Bank |

| (NON-)CORRUPTION | The Control of Corruption index by Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) | World Bank |

| ARTICLES | The natural logarithm of the number of scientific and technical journal articles published in the bank's host country. For 2021 and 2022, the data have been extrapolated using the average annual articles growth of each country | World Bank |

| DEMOCRACY | The bank's host country's democracy index | V-Dem |

| OBS. | Mean | Median | St. dv. | 5th perc. | 95th perc. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCoVaR | 3381 | 1.147 | 1.038 | 0.772 | 0.170 | 2.361 |

| MES | 3381 | 6.372 | 5.127 | 5.546 | 0.094 | 17.353 |

| VaR | 3381 | 1.811 | 1.605 | 1.192 | 0.374 | 3.806 |

| PRESS FREEDOM | 3381 | −0.207 | −0.043 | 1.171 | −1.860 | 1.143 |

| ΔRSF | 3381 | 0.233 | 0.000 | 9.868 | −14.000 | 13.000 |

| ΔFEI | 3381 | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.032 | −0.049 | 0.022 |

| FREEDOM HOUSE | 3381 | 70.529 | 86.000 | 29.397 | 12.000 | 97.000 |

| KILLINGS_INV | 823 | −0.702 | 0.000 | 1.508 | −6.000 | 0.000 |

| GDP | 3381 | 0.027 | 0.025 | 0.035 | −0.035 | 0.083 |

| INDPROD | 2313 | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.056 | −0.106 | 0.096 |

| CRISIS | 3381 | 0.118 | 0.000 | 0.323 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| LNTA | 3374 | 17.937 | 17.667 | 1.692 | 15.604 | 21.322 |

| MB | 3341 | 1.258 | 1.133 | 0.766 | 0.363 | 2.624 |

| EQTA | 3373 | 0.096 | 0.093 | 0.033 | 0.051 | 0.150 |

| LOANS | 3373 | 0.598 | 0.618 | 0.128 | 0.346 | 0.774 |

| ROA | 3369 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.022 |

| COST-TO-INCOME | 3374 | 0.548 | 0.554 | 0.147 | 0.326 | 0.759 |

| NONINT | 3374 | 0.316 | 0.304 | 0.140 | 0.119 | 0.534 |

| COVID (2020–2022) | 3381 | 0.225 | 0.000 | 0.418 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| UNEMP | 3193 | 0.063 | 0.053 | 0.040 | 0.013 | 0.129 |

| INFLATION | 3379 | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.043 | −0.004 | 0.090 |

| GDP VARIANCE | 3381 | 0.063 | 0.034 | 0.097 | 0.002 | 0.287 |

| (NON-)CORRUPTION | 3381 | 0.625 | 0.698 | 0.896 | −0.660 | 2.050 |

| ARTICLES | 3381 | 10.754 | 10.909 | 1.877 | 7.241 | 13.041 |

| DEMOCRACY | 3381 | 6.691 | 7.790 | 2.085 | 2.271 | 9.090 |

- Note: Variable definitions are provided in Table 1.

| Part 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| (1) ΔCoVaR | 1.000 | ||||||

| (2) MES | 0.363*** | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.000) | |||||||

| (3) VaR | 0.800*** | 0.337*** | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||

| (4) PRESS FREEDOM | 0.046*** | 0.076*** | 0.048*** | 1.000 | |||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |||||

| (5) ΔRSF | −0.007 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.682*** | 1.000 | ||

| (0.618) | (0.991) | (0.275) | (0.000) | ||||

| (6) ΔFEI | −0.036** | −0.006 | −0.063*** | 0.595*** | 0.105*** | 1.000 | |

| (0.013) | (0.697) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| (7) FREEDOM HOUSE | 0.123*** | 0.145*** | 0.128*** | 0.611*** | 0.111*** | 0.069*** | 1.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| (8) KILLINGS_INV | −0.052 | 0.133*** | −0.046 | 0.206*** | 0.174*** | 0.101*** | 0.217*** |

| (0.119) | (0.000) | (0.165) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (9) GDP | −0.143*** | −0.295*** | −0.141*** | −0.185*** | −0.058*** | 0.025*** | −0.321*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (10) INDPROD | −0.043** | −0.320*** | −0.011 | −0.049*** | 0.016*** | 0.001 | −0.147*** |

| (0.018) | (0.000) | (0.563) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.773) | (0.000) | |

| (11) CRISIS | 0.034** | 0.270*** | 0.107*** | 0.119*** | 0.037*** | 0.034*** | 0.156*** |

| (0.017) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (12) LNTA | 0.217*** | 0.147*** | 0.111*** | −0.128*** | −0.106*** | −0.028*** | −0.104*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (13) MB | −0.101*** | −0.146*** | −0.195*** | −0.050*** | −0.020*** | −0.012* | −0.074*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.075) | (0.000) | |

| (14) EQTA | −0.092*** | −0.108*** | −0.022 | −0.070*** | −0.006 | −0.012*** | −0.118*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.152) | (0.000) | (0.119) | (0.003) | (0.000) | |

| (15) LOANS | −0.104*** | −0.077*** | −0.057*** | 0.194*** | 0.045*** | 0.022*** | 0.302*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (16) ROA | −0.162*** | −0.279*** | −0.236*** | −0.078*** | −0.028*** | 0.012*** | −0.133*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.000) | |

| (17) COST-TO-INCOME | 0.045*** | 0.168*** | 0.185*** | 0.167*** | 0.068*** | 0.019*** | 0.231*** |

| (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (18) NONINT | 0.011 | −0.024 | −0.023 | −0.044*** | −0.053*** | 0.004 | −0.028*** |

| (0.470) | (0.121) | (0.128) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.353) | (0.000) | |

| (19) COVID (2020–2022) | 0.136*** | 0.131*** | 0.082*** | −0.052*** | −0.045*** | 0.015*** | −0.065*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (20) UNEMP | 0.163*** | 0.240*** | 0.165*** | 0.110*** | 0.082*** | 0.026*** | 0.096*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (21) INF | −0.008 | 0.073*** | 0.005 | −0.182*** | −0.057*** | −0.019*** | −0.270*** |

| (0.591) | (0.000) | (0.721) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (22) GDP VARIANCE | 0.005 | −0.027* | 0.037** | −0.055*** | −0.011*** | −0.021*** | −0.075*** |

| (0.727) | (0.072) | (0.012) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (23) (NON-)CORRUPTION | 0.035** | 0.022 | 0.020 | 0.485*** | 0.083*** | 0.082*** | 0.768*** |

| (0.017) | (0.146) | (0.165) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (24) ARTICLES | 0.127*** | 0.101*** | 0.176*** | 0.283*** | 0.152*** | −0.007** | 0.359*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.045) | (0.000) | |

| (25) DEMOCRACY | 0.134*** | 0.134*** | 0.129*** | 0.599*** | 0.098*** | 0.098*** | 0.965*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Part 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | |

| (9) GDP | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (10) INDPROD | −0.158*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||||

| (11) CRISIS | −0.082*** | 0.800*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||

| (12) LNTA | 0.122*** | −0.215*** | −0.259*** | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

| (13) MB | −0.056*** | 0.058*** | 0.008* | −0.089*** | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.089) | (0.000) | ||||||

| (14) EQTA | −0.028*** | 0.189*** | 0.144*** | −0.096*** | 0.024*** | 1.000 | |||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| (15) LOANS | −0.031*** | 0.012*** | 0.039*** | −0.022*** | −0.192*** | 0.054*** | 1.000 | ||

| (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| (16) ROA | −0.081*** | −0.050*** | −0.074*** | 0.050*** | −0.053*** | −0.026*** | −0.163*** | 1.000 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| (17) COST-TO-INCOME | −0.047*** | 0.074*** | 0.048*** | −0.073*** | 0.043*** | 0.231*** | 0.143*** | −0.043*** | 1.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| (18) NONINT | 0.060*** | −0.115*** | −0.066*** | 0.118*** | −0.326*** | −0.168*** | 0.043*** | −0.033*** | −0.427*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (19) COVID (2020–2022) | 0.017** | −0.027*** | 0.010** | −0.025*** | 0.071*** | 0.045*** | 0.053*** | −0.268*** | 0.064*** |

| (0.027) | (0.000) | (0.037) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (20) UNEMP | 0.122*** | −0.104*** | −0.025*** | −0.190*** | 0.131*** | −0.118*** | −0.001 | −0.048*** | 0.034*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.730) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (21) INF | 0.346*** | −0.130*** | −0.088*** | 0.182*** | −0.068*** | −0.072*** | 0.032*** | −0.057*** | −0.029*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (22) GDP VARIANCE | 0.025*** | 0.090*** | 0.224*** | −0.060*** | −0.006 | 0.049*** | 0.037*** | −0.138*** | 0.067*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.146) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (23) (NON-)CORRUPTION | 0.284*** | 0.092*** | 0.244*** | −0.017*** | −0.004 | −0.006 | 0.040*** | −0.094*** | 0.025*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.298) | (0.327) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (24) ARTICLES | −0.022*** | −0.271*** | −0.098*** | 0.104*** | −0.015*** | −0.085*** | −0.119*** | 0.305*** | −0.111*** |

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| (25) DEMOCRACY | −0.112*** | −0.192*** | −0.132*** | 0.206*** | 0.028*** | −0.090*** | −0.108*** | 0.194*** | −0.114*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Part 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | (21) | (22) | (23) | (24) | (25) | |

| (17) COST-TO-INCOME | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (18) NONINT | −0.021*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||||

| (19) COVID (2020–2022) | −0.062*** | 0.016*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||

| (20) UNEMP | 0.056*** | 0.126*** | −0.103*** | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

| (21) INF | −0.053*** | −0.003 | 0.116*** | −0.002 | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.527) | (0.000) | (0.580) | ||||||

| (22) GDP VARIANCE | −0.039*** | 0.038*** | 0.070*** | 0.077*** | 0.068*** | 1.000 | |||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| (23) (NON-)CORRUPTION | 0.138*** | −0.077*** | −0.019*** | −0.117*** | −0.355*** | −0.101*** | 1.000 | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| (24) ARTICLES | 0.124*** | −0.177*** | 0.072*** | −0.129*** | −0.210*** | −0.111*** | 0.506*** | 1.000 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| (25) DEMOCRACY | 0.200*** | −0.036*** | −0.034*** | 0.005 | −0.279*** | −0.099*** | 0.798*** | 0.404*** | 1.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.195) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

- Note: p-values are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 4 lists all countries with banks in our sample, ranked by PRESS FREEDOM. The table also shows the regime and economic outlook of the countries. We observe that countries with higher levels of press freedom have developed economies and mostly full democracies, while countries with lower levels of press freedom tend to have emerging economies and authoritarian regimes.

| N. | COUNTRY | PRESS FREEDOM | REGIME | ECONOMIC OUTLOOK | N. | COUNTRY | PRESS FREEDOM | REGIME | ECONOMIC OUTLOOK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Canada | 0.554 | Full democracy | Developed | 25 | Poland | 0.106 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 2 | Portugal | 0.551 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 26 | Peru | 0.104 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 3 | Finland | 0.536 | Full democracy | Developed | 27 | South Africa | 0.041 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 4 | Norway | 0.536 | Full democracy | Developed | 28 | South Korea | −0.015 | Full democracy | Developed |

| 5 | Denmark | 0.492 | Full democracy | Developed | 29 | Colombia | −0.166 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 6 | Ireland | 0.461 | Full democracy | Developed | 30 | Indonesia | −0.222 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 7 | USA | 0.452 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 31 | Brazil | −0.242 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 8 | Austria | 0.446 | Full democracy | Developed | 32 | Singapore | −0.518 | Flawed democracy | Developed |

| 9 | Germany | 0.439 | Full democracy | Developed | 33 | Malaysia | −0.593 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 10 | France | 0.424 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 34 | Nigeria | −0.599 | Hybrid regime | Emerging |

| 11 | Chile | 0.422 | Flawed democracy | Emerging | 35 | Mexico | −0.735 | Hybrid regime | Emerging |

| 12 | United Kingdom | 0.409 | Full democracy | Developed | 36 | Thailand | −0.795 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 13 | Belgium | 0.399 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 37 | Pakistan | −0.872 | Hybrid regime | Emerging |

| 14 | The Netherlands | 0.395 | Full democracy | Developed | 38 | India | −1.113 | Flawed democracy | Emerging |

| 15 | Switzerland | 0.388 | Full democracy | Developed | 39 | Türkiye | −1.119 | Hybrid regime | Emerging |

| 16 | Spain | 0.368 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 40 | Kuwait | −1.212 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 17 | Japan | 0.334 | Full democracy | Developed | 41 | Vietnam | −1.217 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 18 | Australia | 0.330 | Full democracy | Developed | 42 | Qatar | −1.230 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 19 | Italy | 0.256 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 43 | Bahrain | −1.365 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 20 | Slovakia | 0.241 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 44 | United Arab Emirates | −1.417 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 21 | Romania | 0.220 | Flawed democracy | Emerging | 45 | Russia | −1.458 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 22 | Czechia | 0.132 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 46 | Saudi Arabia | −1.491 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 23 | Greece | 0.130 | Flawed democracy | Developed | 47 | China | −1.526 | Authoritarian | Emerging |

| 24 | Israel | 0.112 | Flawed democracy | Developed |

- Note: The table presents the list of countries with banks used in our sample ranked by their median level of PRESS FREEDOM. PRESS FREEDOM is the level of press freedom of the bank's host country measured with the first principal component of the change in the country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index, and the Freedom House index. Regime refers to the country's political regime provided by V-Dem. The economic outlook is provided by the IMF.

4 Main Empirical Results

Table 5 presents our baseline regressions that test our hypotheses H1, H2, and H3. We initially present the baseline regressions without control variables and gradually introduce our bank- and country-level variables in the estimations. In the last two columns, we introduce the interaction terms of PRESS FREEDOM with GDP and CRISIS. The results generally confirm our expectations. The coefficient of PRESS FREEDOM is negative and highly statistically significant in all regressions. The relationship is also economically significant as a one standard deviation increase in our press freedom measure is associated with a decrease of up to 2 percentage points in bank systemic risk. Moreover, the coefficient of the interaction term with GDP is positive and highly significant, while the coefficient of the interaction term with CRISIS is negative and highly significant.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | |

| PRESS FREEDOM | −0.017** | −0.018** | −0.018** | −0.034*** | −0.013* |

| (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.007) | |

| PRESS FREEDOM*GDP | 0.601** | ||||

| (0.296) | |||||

| PRESS FREEDOM*CRISIS | −0.196*** | ||||

| (0.054) | |||||

| VaR | 0.260*** | 0.260*** | 0.260*** | 0.262*** | |

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | ||

| LNTA | −0.084* | −0.080 | −0.085* | −0.101* | |

| (0.050) | (0.049) | (0.050) | (0.054) | ||

| MB | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.006 | |

| (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.025) | ||

| EQTA | −1.052 | −1.061 | −1.156* | −1.119* | |

| (0.652) | (0.649) | (0.643) | (0.642) | ||

| LOANS | −0.473** | −0.470** | −0.470** | −0.533*** | |

| (0.198) | (0.200) | (0.201) | (0.204) | ||

| GDP | 0.269 | 0.645 | |||

| (0.529) | (0.609) | ||||

| CRISIS | 0.053 | ||||

| (0.049) | |||||

| COVID (2020–2022) | 0.424*** | 0.419*** | 0.443*** | ||

| (0.110) | (0.110) | (0.116) | |||

| CONSTANT | 0.878 | 2.294 | 2.227 | 2.316 | 2.658 |

| (0.100) | (0.874) | (0.860) | (0.868) | (0.943) | |

| BANK FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| TIME FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| OBS. | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 |

| N. OF BANKS | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 |

| R2 WITHIN | 0.082 | 0.272 | 0.272 | 0.273 | 0.277 |

- Note: The table reports fixed-effects regressions. The dependent variable is ΔCoVaR, which measures banks’ contribution to systemic risk. PRESS FREEDOM is the level of press freedom of the bank's host country measured with the first principal component of the change in the country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index, and the Freedom House index. VaR stands for Value at Risk. LNTA is the natural logarithm of total assets. MB is the market-to-book ratio. EQTA is the ratio of total equity to total assets. LOANS is the ratio of total loans to total assets. GDP is the annual GDP growth of the bank's country. CRISIS equals 1 if the bank's host country has experienced a banking crisis in the given year, 0 otherwise. COVID (2020–2022) equals 1 if the year is 2020, 2021, or 2022 and 0 otherwise. Robust standard errors clustered at the bank level are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Our results reveal that banks have a lower contribution to systemic risk in countries with greater press freedom, in line with our Hypothesis H1. This finding can be attributed to three different mechanisms. First, bank managers perform under tighter market scrutiny and discipline when the press is independent. Second, a free and independent press communicates all information to market participants quicker and thus reduces information asymmetries, enabling bank stability through a more efficient financial system. Finally, a country with higher press freedom is more likely to have a corporate and political culture free from corruption and other unfavorable social phenomena that can prevent the stability of the banking sector.

At the same time, we find that economic growth and banking crises play an important role in the relationship between press freedom and systemic risk. The results suggest that during economic growth, press freedom is not as useful for the banking sector which confirms our Hypothesis H2b. Moreover, consistent with our Hypothesis H3b, press freedom appears to be more useful during banking crises when a free press can stand as a reliable disseminator of information and mitigate the heightened uncertainty, thus enabling all market participants in making informative decisions.

The signs of the statistically significant coefficients of our control variables are generally as expected. ΔCoVaR exhibits a strong positive time-series relationship with value-at-risk (VaR) consistent with Adrian and Brunnermeier (2016). This relationship does not imply causation but rather reflects the commonality in their underlying risk concepts and the way they respond to market dynamics, especially during stressed periods. On the other hand, ΔCoVaR is marginally negatively related to bank capital (EQTA), suggesting that regulators’ efforts to increase capital requirements in recent years are well-placed as more capital helps banks limit their systemic risk. It is also marginally negatively related to bank size (LNTA), which may reflect that larger banks diversify their assets more effectively, implement stronger risk management practices, or benefit from economies of scale, which reduce their vulnerability to shocks. ΔCoVaR has a stronger negative relationship with the share of loans in bank portfolios (LOANS) in our sample, which may occur if loans, particularly well-diversified and lower-risk loans, offer more stable and predictable returns, compared to other, riskier assets. A loan-heavy portfolio might also signal more conservative banking practices, reducing the likelihood of sudden losses or liquidity crises that could destabilize the broader financial system. Finally, the coefficient of COVID (2020–2022) is positive and highly significant, reflecting the extraordinary challenges faced by the global financial system due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the geopolitical turbulence in this period.

5 Robustness Tests

5.1 Alternative Variables

In the first robustness test, we use various alternative measures of systemic risk,11 press freedom, and economic growth. Our main alternative measure of systemic risk is the MES as explained in Section 3.2.2. We also present the results using VaR as the dependent variable that captures banks’ idiosyncratic risk. These results are presented in Table 6. In both cases, the direct relationship with press freedom is negative and highly significant, while the moderating role of GDP growth is also confirmed but only in the regression with VaR as the dependent variable. On the other hand, the coefficient of the interaction term with CRISIS is highly significant in both regressions with the alternative dependent variables.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MES | MES | MES | VaR | VaR | VaR | |

| PRESS FREEDOM | −0.228*** | −0.269*** | −0.163*** | −0.027** | −0.056*** | −0.020 |

| (0.066) | (0.086) | (0.063) | (0.013) | (0.018) | (0.013) | |

| PRESS FREEDOM*GDP | 1.508 | 1.061*** | ||||

| (1.893) | (0.395) | |||||

| PRESS FREEDOM*CRISIS | −0.990** | −0.247*** | ||||

| (0.453) | (0.080) | |||||

| GDP | −0.139 | 0.804 | 0.570 | 1.234 | ||

| (3.643) | (3.873) | (0.868) | (0.935) | |||

| CRISIS | 3.911*** | 0.160 | ||||

| (0.580) | (0.104) | |||||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| BANK FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| TIME FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| OBS. | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 |

| N. OF BANKS | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 |

| R2 WITHIN | 0.428 | 0.428 | 0.456 | 0.061 | 0.062 | 0.064 |

- Note: The table reports fixed-effects regressions. The dependent variables are MES, which measures banks’ contribution to systemic risk, and VaR, which stands for value at risk and measures idiosyncratic risk. PRESS FREEDOM is the level of press freedom of the bank's host country measured with the first principal component of the change in the country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index, and the Freedom House index. GDP is the annual GDP growth of the bank's country. CRISIS equals 1 if the bank's host country has experienced a banking crisis in the given year and 0 otherwise. The same control variables as the ones in Table 5 are used in these regressions. Robust standard errors clustered at the bank level are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

As alternative measures of press freedom, we use the three variables that we employ in our principal component analysis as well as the inverse of the number of killings of journalists in a more limited sample. These results are presented in Table 7 and we observe that our results of the direct relationship between PRESS FREEDOM and ΔCoVaR generally hold as all relevant coefficients are negative and highly significant apart from the coefficient of ΔFEI. At the same time, the coefficients of the interaction term with CRISIS are all negative and highly significant. On the contrary, the coefficients of the interaction term with GDP, although all positive, are generally statistically insignificant as only the one in Column 2 in significant at the 10% level.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | |

| ΔRSF | −0.002** | −0.004** | −0.001 | |||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||||||||||

| ΔFEI | −0.091 | −0.494* | −0.042 | |||||||||

| (0.193) | (0.269) | (0.188) | ||||||||||

| FREEDOM HOUSE | −0.010*** | −0.010*** | −0.010*** | |||||||||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | ||||||||||

| KILLINGS_INV | −0.073*** | −0.054 | −0.029*** | |||||||||

| (0.013) | (0.065) | (0.006) | ||||||||||

| X*GDP | 0.073* | 14.445 | 0.001 | 0.949 | ||||||||

| (0.039) | (10.074) | (0.011) | (2.145) | |||||||||

| X*CRISIS | −0.012*** | −6.347** | −0.006*** | −0.215*** | ||||||||

| (0.005) | (3.031) | (0.002) | (0.051) | |||||||||

| GDP | 0.213 | 0.367 | 0.289 | 0.481 | 0.169 | 0.103 | 4.317*** | 4.877*** | ||||

| (0.536) | (0.560) | (0.533) | (0.528) | (0.524) | (0.696) | (1.280) | (0.933) | |||||

| CRISIS | −0.006 | −0.034 | 0.497*** | −0.154*** | ||||||||

| (0.045) | (0.046) | (0.166) | (0.041) | |||||||||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| BANK FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| TIME FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| OBS. | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 823 | 823 | 823 |

| N. OF BANKS | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| R2 WITHIN | 0.272 | 0.273 | 0.275 | 0.271 | 0.272 | 0.272 | 0.275 | 0.275 | 0.277 | 0.417 | 0.369 | 0.342 |

- Note: The table reports fixed-effects regressions. The dependent variable is ΔCoVaR, which measures banks’ contribution to systemic risk. ΔRSF is the change in the country's RSF ranking. ΔFEI is the change in the freedom of expression index. FREEDOM HOUSE is the Freedom House index. KILLINGS_INV is the inverse of the number of killings of journalists. X denotes the respective measure of press freedom used in each model. GDP is the annual GDP growth of the bank's country. CRISIS equals 1 if the bank's host country has experienced a banking crisis in the given year and 0 otherwise. The same control variables as the ones in Table 5 are used in these regressions. Robust standard errors clustered at the bank level are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Considering that in most regressions presented in Tables 6 and 7 the results with GDP do not hold, we also employ industrial production growth12 as an alternative to GDP growth to further test this finding in our baseline regressions. We present the results of this test in Table 8 using PRESS FREEDOM and its components as the main independent variables. Although these results are presented for a constrained sample, we observe that our findings hold as the coefficient of the interaction term with INDPROD is positive and highly significant in three of the four regressions.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | |

| PRESS FREEDOM | −0.033** | |||

| (0.013) | ||||

| ΔRSF | −0.003** | |||

| (0.001) | ||||

| ΔFEI | −0.547* | |||

| (0.313) | ||||

| FREEDOM HOUSE | −0.012** | |||

| (0.005) | ||||

| X*INDPROD | 0.831*** | 0.091*** | 21.396*** | 0.020 |

| (0.213) | (0.030) | (6.375) | (0.015) | |

| INDPROD | −0.469 | −0.551 | −0.297 | −2.163* |

| (0.404) | (0.388) | (0.423) | (1.297) | |

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| BANK FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| TIME FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| OBS. | 2315 | 2315 | 2315 | 2315 |

| N. OF BANKS | 173 | 173 | 173 | 173 |

| R2 WITHIN | 0.313 | 0.313 | 0.309 | 0.311 |

- Note: The table reports fixed-effects regressions. The dependent variable is ΔCoVaR, which measures banks’ contribution to systemic risk. PRESS FREEDOM is the level of press freedom of the bank's host country measured with the first principal component of the change in the country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index, and the Freedom House index. ΔRSF is the change in the country's RSF ranking. ΔFEI is the change in the freedom of expression index. FREEDOM HOUSE is the Freedom House index. KILLINGS_INV is the inverse of the number of killings of journalists. X denotes the respective measure of press freedom used in each model. INDPROD is the annual industrial production growth of the bank's host country. The same control variables as the ones in Table 5 are used in these regressions. Robust standard errors clustered at the bank level are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

5.2 Expanded Set of Bank- and Country-Level Control Variables

If there are consistent variations in country-level characteristics, and these variations influence both our measures of press freedom and systemic risk, excluding these country-level variables could lead to potential issues of endogeneity. At the same time, the omitted variables bias can also arise from bank-level variables that may affect bank systemic risk. To alleviate this concern, we expand our baseline regressions by incorporating more bank- and country-level variables. More specifically, we further control for non-interest income (NONINT), profitability (ROA), operational efficiency (COST-TO-INCOME), macroeconomic uncertainty (GDP VARIANCE), inflation (INF), unemployment (UNEMP), and control of corruption ((NON-)CORRUPTION). We present these results in Table 9. We observe that GDP VARIANCE that was previously found to contribute to systemic risk (Anginer, Demirguc-Kunt, and Zhu 2014) has a negative and significant coefficient. Moreover, (NON-)CORRUPTION has a negative and highly significant coefficient. This suggests that as corruption decreases (or control of corruption improves), systemic risk is reduced, highlighting the stabilizing effect of better governance on the banking sector. Despite the inclusion of these new control variables, our results hold.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | |

| PRESS FREEDOM | −0.024*** | −0.042*** | −0.019** |

| (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.008) | |

| PRESS FREEDOM*GDP | 0.694** | ||

| (0.351) | |||

| PRESS FREEDOM*CRISIS | −0.216*** | ||

| (0.054) | |||

| NONINT | 0.044 | 0.049 | 0.077 |

| (0.152) | (0.153) | (0.159) | |

| ROA | −0.611 | −0.918 | −1.049 |

| (4.838) | (4.904) | (5.227) | |

| COST-TO-INCOME | −0.109 | −0.105 | −0.159 |

| (0.208) | (0.208) | (0.227) | |

| GDP VARIANCE | −0.367* | −0.337* | −0.383** |

| (0.195) | (0.193) | (0.185) | |

| INFLATION | 0.613 | 0.497 | 0.382 |

| (0.768) | (0.777) | (0.765) | |

| UNEMPLOYMENT | 0.928 | 0.911 | 1.214 |

| (0.755) | (0.753) | (0.741) | |

| (NON-)CORRUPTION | −0.206** | −0.214*** | −0.183** |

| (0.079) | (0.080) | (0.078) | |

| PREVIOUS CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES |

| BANK FE | YES | YES | YES |

| TIME FE | YES | YES | YES |

| OBS. | 3145 | 3145 | 3145 |

| N. OF BANKS | 259 | 259 | 259 |

| R2 WITHIN | 0.282 | 0.283 | 0.288 |

- Note: The table reports fixed-effects regressions. The dependent variable is ΔCoVaR, which measures banks’ contribution to systemic risk. PRESS FREEDOM is the level of press freedom of the bank's host country measured with the first principal component of the change in the country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index, and the Freedom House index. NONINT is the ratio of non-interest income to total revenue. COST-TO-INCOME is the ratio of operating cost to operating income. ROA stands for the return on assets. GDP VARIANCE is the variance of the bank's host country's GDP growth in the previous five years. INFLATION is the annual inflation rate of the bank's host country. UNEMPLOYMENT is the total unemployment rate of the bank's host country. (NON-)CORRUPTION is the Control of Corruption index by Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). GDP is the annual GDP growth of the bank's host country. CRISIS equals 1 if the bank's host country has experienced a banking crisis in the given year and 0 otherwise. The same control variables as the ones in Table 5 are also used in these regressions. Robust standard errors clustered at the bank level are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

5.3 2SLS

We also attempt to control for endogeneity by using the instrumental variables 2SLS estimator. The level of systemic risk in a banking sector may eventually influence the extent of press freedom. During times of crisis or heightened risk, there might be pressures on the media to align with government narratives, avoid reporting that could exacerbate panic, or self-censor to maintain social stability. As a result, governments may impose restrictions on information flow, impacting the ability of the press to operate freely.

Our first instrument is the level of academic freedom in the bank's host country. Declines in press freedom are more common in countries with lower average levels of education (J. Nguyen et al. 2021) since the latter acts as a key predictor of the demand for press freedom (Nisbet and Stoycheff 2013). When scholars, educators, and researchers are afforded the liberty to explore diverse perspectives, question prevailing narratives, and engage in rigorous intellectual inquiry without fear of censorship or repercussions, it establishes a precedent for a broader culture of openness. This culture, extending from academic institutions to the media, fosters an environment where journalists feel empowered to critically examine and report on various issues without constraints. The protection of academic freedom, with its emphasis on free expression and the pursuit of knowledge, contributes significantly to the overall health of a democratic society (Cole 2017). This, in turn, fosters a robust and independent press that plays a crucial role in holding power accountable and informing the public. We measure academic freedom using the volume of scientific articles published in the bank's host country (measured by the natural logarithm of the total number of articles) on the basis that academic freedom is the freedom to do academic work. As a result, a higher volume of scientific publications reflects greater academic freedom.

Our second instrument is the level of democracy in the bank's host country. Democratic regimes facilitate press freedom by fostering a system where diverse voices can be heard, promoting transparency and accountability, which are essential pillars for free and vibrant media. On the other hand, in an autocratic system dominated by the supremacy of political authority, which dictates the legal, political, and economic parameters within which journalists function, those in power may exploit their influential position to manipulate the press, disseminate propaganda, and control information channels. The empirical literature supports democracy as an important determinant of press freedom showing that democracies lead to significantly higher levels of media freedom (Stier 2015) and that democratic regimes are more transparent (Hollyer, Rosendorff, and Vreeland 2011).

The results of the 2SLS regressions are presented in Table 10 and fully confirm our findings. First, the results of the first stage regressions confirm our expectations regarding the contribution of academic freedom and democracy to press freedom as the coefficients of both our instruments are positive and highly significant. Second, the coefficients of PRESS FREEDOM and its interaction terms with GDP and CRISIS maintain the original signs and are also highly significant. In Columns 2, 3, and 4, the p-value of the Sargan–Hansen test suggests that we cannot reject the null hypothesis, which increases our confidence that the instruments selected are appropriate.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRESS FREEDOM | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | |

| PRESS FREEDOM | −0.225** | −0.034*** | −0.013* | |

| (0.114) | (0.011) | (0.007) | ||

| PRESS FREEDOM*GDP | 0.601** | |||

| (0.296) | ||||

| PRESS FREEDOM*CRISIS | −0.196*** | |||

| (0.054) | ||||

| GDP | 0.142 | 0.645 | ||

| (0.559) | (0.609) | |||

| CRISIS | 0.053 | |||

| (0.049) | ||||

| ARTICLES | 0.298*** | |||

| (0.088) | ||||

| DEMOCRACY | 0.162*** | |||

| (0.053) | ||||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| BANK FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| TIME FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| OBS. | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 | 3381 |

| N. OF BANKS | 259 | 259 | 259 | 259 |

| R2 WITHIN | 0.082 | 0.152 | 0.273 | 0.277 |

| SARGAN–HANSEN | 0.679 | 0.987 | 0.324 | |

| IV STAGE | FIRST-STAGE | SECOND-STAGE | SECOND-STAGE | SECOND-STAGE |

- Note: The table reports fixed-effects 2SLS regressions. The dependent variable in the first stage is PRESS FREEDOM, which is the level of press freedom of the bank's host country measured with the first principal component of the change in the country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index, and the Freedom House index. The dependent variable in the second stage is ΔCoVaR, which measures banks’ contribution to systemic risk. GDP is the annual GDP growth of the bank's country. CRISIS equals 1 if the bank's host country has experienced a banking crisis in the given year and 0 otherwise. ARTICLES and DEMOCRACY are used as instruments. ARTICLES is the natural logarithm of the number of scientific and technical journal articles published in the bank's host country. DEMOCRACY is the democracy index by the Economist Intelligence Unit of the bank's host country. The same control variables as the ones in Table 5 are used in these regressions. Robust standard errors clustered at the bank level are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

5.4 Subsample Analysis

Our sample consists of banks from various countries with a diverse background. Some countries may have a completely different bank regulatory framework compared to the international standards that prevail in the advanced economies. At the same time, different political regimes could play an important role in press freedom too. In this test, we attempt to account for such discrepancies by conducting subsample analysis, and the results are presented in Table 11. First, we exclude the banks that do not operate in countries that are member states of the BCBS. Although the BCBS standards can vary in their application across legislations, they aim to create a level playing field in the international banking sector with a homogeneous set of rules for banks. Our results hold for banks in countries that are BCBS member-states. Second, we split the sample based on the type of regime that holds in the bank's host country, that is, Democratic (including fully democratic, flawed democratic and hybrid regimes) and Authoritarian.13 We observe that the direct relationship holds in both samples, and it is stronger in authoritarian regimes. The coefficients of the interaction terms have the expected signs in the democratic regimes sample, although only the coefficient of the interaction term with CRISIS is highly significant. The coefficients of the interaction terms have the opposite signs in the authoritarian regimes sample, and the coefficient of the interaction term with GDP is also slightly significant at the 10% level. We contend that this discrepancy is a result of the adeptness shown by authoritarian regimes in shielding their banking systems from external risks, consequently diminishing interconnectedness. In such a context, the impact of press freedom on mitigating systemic risk during times of crisis or lower economic growth appears limited.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCBS | Democratic regimes | Authoritarian regimes | |||||||

| ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | ΔCoVaR | |

| PRESS FREEDOM | −0.019* | −0.046*** | −0.013 | −0.019** | −0.033*** | −0.012 | −0.055*** | −0.027 | −0.063*** |

| (0.010) | (0.014) | (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.007) | (0.019) | (0.026) | (0.020) | |

| PRESS FREEDOM*GDP | 1.090*** | 0.532 | −0.927* | ||||||

| (0.366) | (0.348) | (0.528) | |||||||

| PRESS FREEDOM*CRISIS | −0.198*** | −0.281*** | 0.169 | ||||||

| (0.057) | (0.064) | (0.122) | |||||||

| GDP | 0.529 | 1.051 | −0.080 | 0.193 | −0.361 | −1.667 | |||

| (0.741) | (0.891) | (0.701) | (0.754) | (0.713) | (1.091) | ||||

| CRISIS | 0.045 | 0.100* | 0.330* | ||||||

| (0.052) | (0.051) | (0.181) | |||||||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| BANK FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| TIME FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| OBS. | 2674 | 2674 | 2674 | 2768 | 2768 | 2768 | 613 | 613 | 613 |

| N. OF BANKS | 202 | 202 | 202 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| R2 WITHIN | 0.285 | 0.288 | 0.291 | 0.291 | 0.292 | 0.299 | 0.279 | 0.282 | 0.281 |

- Note: The table reports fixed-effects regressions. The dependent variable is ΔCoVaR, which measures banks’ contribution to systemic risk. PRESS FREEDOM is the level of press freedom of the bank's host country measured with the first principal component of the change in the country's RSF ranking, the change in the freedom of expression index, and the Freedom House index. GDP is the annual GDP growth of the bank's country. CRISIS equals 1 if the bank's host country has experienced a banking crisis in the given year and 0 otherwise. Columns 1 to 3 include only banks in countries that are member-states of the BCBS. Columns 4 to 6 include only banks in countries with a regime classified as full democratic, flawed democratic, or hybrid, while Columns 7 to 9 include only banks in countries with a regime classified as authoritarian. The same control variables as the ones in Table 5 are used in these regressions. Robust standard errors clustered at the bank level are reported in parentheses.

- ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

5.5 Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA)

- 1.

Why will Y be absent if X is absent? If there is an absence of press freedom, it implies limited or no independent scrutiny of financial institutions and government policies. Press freedom serves as a check and balance system by providing information, investigating potential risks, and holding institutions accountable. Without press freedom, there is a higher likelihood of unchecked financial practices, lack of transparency, and inadequate disclosure of risks. This lack of oversight can lead to an environment where systemic risk in the banking sector can go unnoticed and unaddressed until it escalates to a critical level.

- 2.

Why will X always be present if Y is present? When systemic stability exists in the banking sector, it often correlates with a broader stability in the economic and political landscape. This stability creates an environment where various sectors can thrive, including the media and information industry. In a financially secure and stable setting, there is generally a higher likelihood of press freedom being present. The reason lies in the symbiotic relationship between a stable banking sector and a robust information ecosystem. A financially stable environment fosters the growth of media outlets, investigative journalism, and independent voices, contributing to a society where the absence of undue pressure on the media allows for the free flow of information and scrutiny of institutions, which is essential for press freedom.

- 3.

Why can other concepts not compensate for the absence of X? While a country without press freedom may have other advantages, such as economic resources or strategic geographical location, these factors cannot adequately compensate for the absence of press freedom when it comes to mitigating systemic risk. Press freedom plays a unique role in providing unbiased information, fostering transparency, and acting as a watchdog over financial institutions and government policies. Other advantages may attract investment but cannot replace the essential function of the press in ensuring that risks are identified, communicated, and addressed promptly. Therefore, a lack of press freedom creates a critical gap in the oversight mechanism that other positive attributes cannot fully substitute.

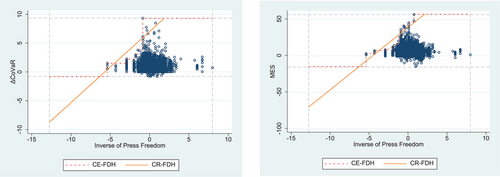

The results presented in Figure 3 support our arguments. We use the lagged values of the inverse14 of PRESS FREEDOM and show the effect on ΔCoVaR and MES. Using the CE-FDH and CR-FDH ceilings, the effect size on ΔCoVaR is 0.510 (p-value = 0.000) and 0.625 (p-value = 0.000), respectively. The relevant effect size values for MES are 0.516 (p-value = 0.000) and 0.634 (p-value = 0.000). According to Dul (2016), the effects on ΔCoVaR and MES can be considered as large suggesting that the absence of press freedom is indeed a necessary condition for Systemic risk.

5.6 Price Informativeness and Corruption

In our theoretical framework, we argue that press freedom can reduce bank systemic risk by reducing information asymmetries or signaling cultural differences, such as higher levels of corruption in countries with limited press freedom. While we explore these channels as potential mediating effects, our findings do not provide confirming evidence. First, we do not find a connection between press freedom and price informativeness measured by bid–ask spreads and price synchronicity as Kim et al. (2014) suggest. Second, although we find a negative association between press freedom and corruption, we fail to find a mediating effect of corruption in the relationship between press freedom and systemic risk. As it can be seen in Table 9, the coefficient of press freedom increases rather than decreases when we add corruption as an independent variable. For this reason, we suggest that a combination of these factors may explain the negative relationship between press freedom and systemic risk.

6 Conclusions and Policy Implications

The press can exert significant market discipline on banks through various channels when unbiased. However, even countries with advanced economies suffer from poor levels of press freedom and whether this affects the stability of the banking sector has been largely neglected by the extant literature. In this paper, we aim to fill this apparent gap by examining the relationship between press freedom and systemic risk, as well as the moderating role of economic growth and banking crises.

Our empirical analysis shows in different ways that press freedom is negatively associated with bank systemic risk. We argue that this finding can be attributed to the market discipline imposed by the press, the reduction of information asymmetries, and cultural characteristics in countries with high press freedom, such as low corruption. Our results also indicate the importance of economic growth and banking crises in this relationship. More specifically, we show that press freedom is less useful for bank stability during economic growth but more useful during banking crises. During economic downturns or banking crises, information asymmetries increase and the press can prove more effective in disseminating information to market participants who can make informed decisions.

These findings have important policy implications across different areas. First, they highlight that restricting press freedom's ability to report the truth can have wider repercussions that influence the financial sector. The United Nations has recently expressed the need for urgent action to prevent the observed decline in media freedom (Khan 2022), while in the same direction, the UK government established the National Action Plan for the Safety of Journalists in 2021. Our results support the introduction of these policies by showing that a declining press freedom has broader consequences. Second, our findings indicate that policymakers need to look closer into the build-up of systemic risk during periods of economic growth. More importantly, regulators need to encourage greater levels of press freedom in countries that are experiencing economic and financial adversities, as it can potentially help mitigate systemic risk more, compared to periods of economic growth. Third, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, a series of tighter capital and liquidity requirements among others have been introduced by international and national regulatory bodies. Our results indicate that policymakers must place particular emphasis to the wider cultural environment that banks operate in to ensure a stable banking system that supports economic growth and social welfare.

Future research may investigate the role of financial literacy in enhancing the impact of press freedom on the financial sector. Limitations in the measurement of financial literacy at the moment prevent this important research, which can be essential for understanding how well-informed citizens can leverage media transparency to improve financial decision-making.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.