Does corporate governance matter in competitive industries? Evidence from brokerage mergers and closures

Abstract

We document that firms in competitive industries experience significantly more deterioration in financial reporting quality after a reduction in analyst coverage due to brokerage closures or mergers, as compared to firms in noncompetitive industries. Most of the effects are mainly driven by firms with smaller initial analyst coverage, lower institutional ownership and greater financial constraints. Importantly, we further show that after brokerage exits, managerial slack increases more for firms in noncompetitive than competitive industries. Consistent with the notion that agency manifestation can take different forms, we provide evidence that competition may curtail some agency issues, such as managerial slack, while also exacerbating other agency issues, such as financial misreporting.

1 INTRODUCTION

Although there is a general consensus in the accounting and finance literature that product market competition affects agency problems, research thus far has documented mixed evidence on the direction of this impact. Product market competition can serve as a strong governance mechanism that reduces agency costs by exerting a disciplinary effect and mitigating managerial slack; however, it can also have undesired consequences. For example, Shleifer (2004) argued that firms facing higher competition are more likely to manipulate earnings to signal strong performance.1 Understanding the effect of competition on agency conflicts and the possible resultant conflicts has profound implications for policymakers and corporate stakeholders in designing optimal governance structures.

The shareholder–manager agency conflict can take many non-mutually exclusive forms, such as managerial slack (Holmström, 1979), empire building (Jensen, 1986; Stulz, 1990), overconfidence (Roll, 1986), career incentive problems (Holmström, 1999) and creative accounting to manipulate shareholder beliefs (Tirole, 2006). Although competition is often seen as an effective mechanism to mitigate these agency issues, it is unlikely to address all on its own and cannot be treated simply as a “good” or “bad” governance mechanism that mitigates all agency costs. Instead, we argue that competition may reduce certain agency problems, such as managerial slack (i.e., the disciplining side of competition), whereas encouraging other agency problems, such as creative accounting practices and financial manipulation (i.e., the dark side of competition). When faced with severe industry competition, managers have incentives to inflate performance or engage in earnings smoothing in an attempt to make earnings look less variable over time (Goel & Thakor, 2003). The engagement in earnings manipulation does not need to coincide with empire-building or managerial slack. Rather, earnings management can be used to manipulate the market perception and “portray business as normal” to meet capital market expectations. This raises an interesting point: solving one agency problem may give rise to a different one.2

The key rationale behind our argument is that both reductions in managerial slack and involvement in earnings management can offer firms a better chance of survival. Competition unambiguously reduces a firm's survival prospect as it lowers the firm's market power and profit margins, heightens predation risk, raises the cost of capital, increases the cost of proprietary disclosure, and elevates managerial career concerns. Under intense competitive pressure, firms can either strive to stay the fittest by cutting managerial slack and improving corporate efficiency or adopt measures, such as earnings management, to create the appearance of being the fittest to increase their chance of survival. When there is a disequilibrium of corporate governance, the marginal benefits of misreporting exceed the marginal costs for firms operating in highly competitive industries where survival is a first-order priority. This argument predicts that firms in competitive industries misreport more relative to noncompetitive industries when corporate governance is weakened.

To empirically test the role of competition in financial reporting, we incorporate two quasi-natural experiments: staggered brokerage closures and brokerage mergers.3 Analyst terminations resulting from brokerage closures and mergers generate a decrease in analyst coverage that is unrelated to treated firms’ fundamentals. These events provide an ideal research setting for testing the effect of competition on financial reporting quality when corporate governance weakens, as the governance role of analysts is well documented in the literature (Chen et al., 2015; Yu, 2008).4 We employ a triple difference-in-differences approach (DDD). The first two differences compare the financial reporting quality before and after analyst coverage shocks for treatment and control groups. The third difference estimates whether the effect of the reduction in analyst coverage is different for firms in competitive and noncompetitive industries.

We proxy for financial reporting quality using two commonly used measures in the literature: the absolute value of discretionary accruals and accounting restatements. Because managers have incentives to manage earnings not only upward but also downward to achieve a stable earnings performance, we use absolute discretionary accruals to capture earnings management in both directions. As discretionary accruals may be subject to estimation errors, we also use accounting restatements to capture intentional misrepresentation. Additionally, we incorporate various alternative measures, including signed discretionary accruals, entropy-balanced accruals, discretionary current accruals and financial statement frauds reported in the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC) Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAERs). These proxies provide a holistic approach to measuring a firm's financial quality. Our main measure of competition is the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index calculated using sales, and we supplement it with alternative measures, including firm-by-firm pairwise similarity scores and firm-level product fluidity from the 10-K text-based industry classification and Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) measured by the Census Bureau's Economic Survey, which covers both public and private establishments.

Using a sample from 1988 to 2018 covering 58 brokerage closures and mergers, we find that discretionary accruals and financial restatements in treated firms significantly increase after reductions in analyst coverage. More importantly, consistent with the dark side view of competition, we find that the increase in financial misreporting after brokerage closures and mergers is more significant for competitive than noncompetitive industries. The economic significance is meaningful: A one standard deviation increase in competition is associated with an 8.3% increase in discretionary accruals and a 14.4% increase in restatements after a reduction in analyst coverage. These findings show that product market competition alone cannot effectively reduce financial manipulation; on the contrary, it creates pressure for more misreporting when analyst monitoring is weakened. We confirm that the main results are not sensitive to alternative variable measures or model specifications. We further perform a dynamic test and show that reverse causality is not a concern and that there is an immediate consequence to the disequilibrium in corporate governance. Our findings call attention to the incentive for firms to misreport and highlight the severity of pressure from industry competition.

We conduct several cross-sectional analyses to provide further support for our main findings. Our first set of tests shows that the main results are more pronounced for firms where analyst coverage is more important: those with lower initial analyst coverage, those losing higher quality analysts and those with lower institutional ownership. These findings substantiate our argument of the dark side view of competition that firms in competitive industries may benefit from increased monitoring. Our second set of tests reveals that the main results are more pronounced for firms with higher financial constraints, consistent with the notion that firms in competitive industries face more pressure than noncompetitive industries to manage earnings, mitigate financial constraints and survive. In additional analyses, we show that competition reduces other types of agency manifestations, such as managerial slack and expropriation (Chen et al., 2015; Giroud & Mueller, 2010). Interestingly, we find no evidence that firms in competitive industries manage real activities more than noncompetitive industries when governance monitoring weakens, presumably because real activities management negatively impacts a firm's future performance, impairing its competitive status against industry rivals. Collectively, these results corroborate our claim that managerial misbehavior within the agency context is multidimensional, and that competition may have a different effect and policy implication depending on the manifestation of the agency issue.

We contribute to the existing literature on product market competition and add to the debate regarding the effectiveness of competition as a corporate governance mechanism. Specifically, we reconcile seemingly inconsistent prior studies and highlight the multifaceted nature of agency conflicts: Although competition improves overall corporate efficiency and reduces managerial slack, it also incentivizes managers to manipulate financial statements when analyst monitoring weakens. The findings in our study imply that managers facing intensive pressure from product market competition are more inclined to exploit the decline in market monitoring. Our study concludes that competition cannot fully substitute for effective corporate governance, which offers important policy implications for regulators and corporate leaders. We advocate that highly competitive industries still benefit from market monitoring to deter certain opportunistic behavior, such as financial misreporting.

We also contribute to the understanding of the choice between real earnings management and accrual earnings management under the natural experiments setting. We find that the relationship between competition and earnings management decisions hinges upon the relative cost to a firm's competitive position; we also find that managers do not treat these decisions equally, consistent with the idea that real activities management deviates from optimal operational decisions and may harm a firm's long-term performance (Graham et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2018; Zang, 2012).

2 HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

There are two competing views on the role of product market competition in corporate governance. Traditionally, economists consider competition a powerful driving force for efficiency because inefficient managers who fail to maximize a company's value are likely to be exploited and eliminated by competitors (e.g., Alchian, 1950; Hart, 1983). In support of this stance, empirical studies find that industries with lower levels of competition tend to display weaker performance (Jiang et al., 2015; Nickell, 1996), and the effect of corporate governance on firm value decreases as competition intensifies. This disciplinary view of competition concludes that competition can substitute for rigorous corporate governance, and that firms in a noncompetitive industry benefit more from a sound governance structure (e.g., Bodnaruk et al., 2013; Chhaochharia et al., 2017; Giroud & Mueller, 2010). However, this perspective has faced many challenges, with studies indicating that product market competition has a dark side that may exacerbate agency problems (e.g., Datta et al., 2013; Karuna, 2007; Markarian & Santalo, 2014; Scharfstein, 1988; Shi et al., 2018; Stein, 1988). This dark side view of competition contends that competition may, in some instances, intensify agency problems and, at best, should be considered a complement to corporate governance.

We choose to focus on financial misreporting as our area of study, as it provides a valuable context for exploring the governance role of competition. Financial reporting outcomes are presented directly to external stakeholders to represent a firm's financial performance, and managers have substantial discretion in this regard. Instances like WorldCom and Enron, alongside academic research, have demonstrated financial misreporting as an agency problem (Jensen, 2005). For example, empirical studies show that a lack of strong corporate governance mechanisms, such as independent board of directors, effective audit committee or well-designed ownership structure, is linked to a greater likelihood of firms reporting financial restatements and higher levels of discretionary accruals, indicating financial misreporting is a consequence of weak corporate governance (e.g., Agrawal & Chadha, 2005; Baber et al., 2012; Bowen et al., 2008; Cornett et al., 2008; Dechow et al., 1996; Klein, 2002). Building upon this literature, we study financial misreporting as it offers an interesting and direct context to investigate the governance effect of competition.

- H1a: Financial misreporting increases more in noncompetitive industries relative to competitive industries when corporate governance weakens.

- H1b: Financial misreporting increases more in competitive industries relative to noncompetitive industries when corporate governance weakens.

It is important to note that H1b does not necessarily contradict prior research that finds competition decreases managerial slack. We surmise that the key to reconciling these seemingly contradictory viewpoints lies in recognizing the multifaceted nature of agency issues. The effect of competition within an agency context varies depending on the specific agency issue under examination. “While we agree that product market competition is probably the most powerful force toward economic efficiency in the world, we are skeptical that it alone can solve the problem of corporate governance” (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997, p.738). Competition may effectively mitigate certain agency problems, such as managerial slack, but it can also exert pressure on management to deliver superior financial performance (Shleifer, 2004). In summary, we contend that competition alone cannot entirely eliminate agency problems and may, in some cases, exacerbate specific agency issues, such as financial misreporting.

Both increases in financial misreporting and decreases in managerial slack can be outcomes of market competition, even though they may appear opposite when viewed from the perspective of reducing agency costs. In a competitive market, survival becomes paramount, and managers may feel compelled to adopt any available strategy possible to avoid being eliminated. Models by Stein (2003) and Tirole (2006) suggest a greater likelihood of herding behavior among managers facing greater market competition. Their models imply that when one firm decides to reduce managerial slack to enhance efficiency or manage earnings to project an appearance of efficiency, peer firms in a more competitive industry are more likely to imitate these behaviors. This is because the marginal benefit (or the opportunity cost) of such strategies becomes more significant when survival becomes a top priority in highly competitive industries. We do not formally hypothesize managerial slack, as the effect of competition on managerial slack has been documented in prior research by Giroud and Mueller (2010) and Chen et al. (2015). Instead, we revisit their findings and incorporate them into our research setting in Section 5.3, as we explore these dynamics further.

3 EMPIRICAL DESIGN

3.1 Research setting

To test our hypotheses, we use brokerage closures and brokerage mergers as two quasi-natural experiments and incorporate a DDD research design. Many existing studies have validated this empirical setting and showed that analyst coverage is likely to be exogenously reduced after brokerage closures and mergers (e.g., Chen et al., 2015; Derrien & Kecskés, 2013; Hong & Kacperczyk, 2010; Irani & Oesch, 2013; Kelly & Ljungqvist, 2012). As analyst coverage in equilibrium is likely endogenous, the drop in analyst coverage in these quasi-natural experiments mitigates concerns of omitted variables and reverse causality that may bias our estimation results.

We begin by verifying the assumption that brokerage closures and mergers lead to a decrease in analyst coverage. To show the validity of this assumption, we plot the mean difference in analyst coverage between the treatment group (i.e., firms that experience a brokerage closure or merger in year t) and the control group (i.e., firms that have not experienced a brokerage closure or merger by year t) during a 6-year period around the events. Figure 1 shows that the difference in mean analyst coverage between treatment and control firms is 0.05 analysts pretreatment. This difference changes to −0.94 analysts immediately posttreatment, a significant decrease of 0.99 analysts between year t-1 and year t. This figure suggests that brokerage closures and mergers lead to a decrease in analyst coverage in treatment firms relative to control firms. Consistent with prior literature, the figure also shows that most of the treatment firms regain their analyst coverage within 3 years of the termination and that the termination effect mainly occurs within 1 year of the closure or merger (Chen et al., 2015; Derrien & Kecskés, 2013).

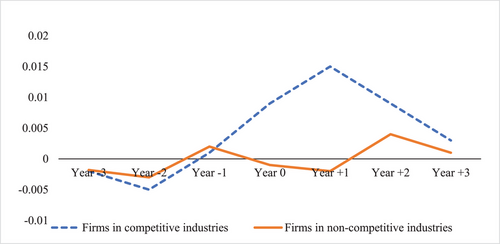

The identification of a DDD method relies on the parallel trends assumption. That is, outcome variables move in parallel trends in the absence of the treatment. Although the assumption is not directly testable, we follow Roberts and Whited (2012) to visualize the changes in discretionary accruals over the 6-year period around the treatment. Figure 2 plots the mean difference in discretionary accruals between treatment and control firms during the 3 years before and after analyst terminations. Two notable findings are presented in the graph. First, the change in financial reporting quality occurs only after the shocks, alleviating the threat of reverse causality. Second and more importantly, the effect is mostly driven by the difference between treatment and control firms within competitive industries. These results mitigate concerns about the parallel trends assumption and provide an initial outlook for our empirical findings.

3.2 Variable definitions

We proxy for financial reporting quality using two measures commonly used in the literature: earnings management, calculated as the absolute value of discretionary accruals and accounting restatements. Earnings management is calculated using the modified Jones model controlling for performance (Kothari et al., 2005). We use the absolute value of discretionary accruals, ABS_DA, to capture both upward and downward earnings management (Armstrong et al., 2013; Bergstresser & Philippon, 2006; Yu, 2008).6 Following Armstrong et al. (2013), we retain accounting restatements related to fraud, misreporting or a Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) investigation in the Audit Analytics dataset to focus on only restatements related to intentional misrepresentation rather than clerical errors. Restatement is set to one if a firm i restates year t’s annual statement and zero otherwise. Our primary measure of product market competition is the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (Competition), defined based on the 3-digit SIC code, a compromise between too coarse and too narrow a partition (Giroud & Mueller, 2010). We multiply it by minus one so that a higher Competition implies stronger competition.7

We follow the literature in selecting our control variables: the natural logarithm of total assets to control for firm size, market-to-book ratio to account for investment opportunities, return on assets (ROA) for financial performance, the asset growth rate for growth and total debt-to-asset ratio for leverage. We also control for cash flow volatility, as Hribar and Nichols (2007) demonstrated that earnings management can be correlated with cash flow volatility. We provide more detailed variable definitions in Appendix A.

3.3 Data and sample construction

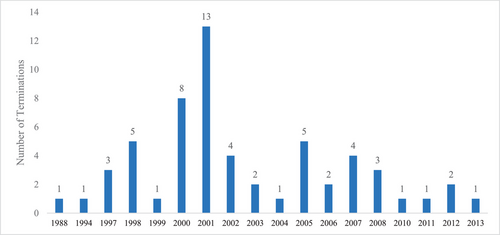

Our sample construction process begins with all firms in the Compustat universe between 1988 and 2018.8 We use brokerage merger events identified in Hong and Kacperczyk (2010) and follow Kelly and Ljungqvist (2012) to collect brokerage closure events. Specifically, Kacperczyk identifies broker mergers from Thomson's SDC Mergers and Acquisition database and requires the target to come from the Security Brokers, Dealers and Flotation Companies industry (SIC code 6211), with both merging houses covering at least two of the same stocks. We identify broker closures as those that disappeared from I/B/E/S during our sample period. We manually search press releases in Factiva to confirm the closures. In total, we identify 58 analyst termination events, including 22 brokerage closures and 36 brokerage mergers. Figure 3 plots a histogram of the 58 analyst termination events, and Table 1 lists the annual distribution of the brokerage closures and brokerage mergers.

| (1) | (2) | (1) + (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Brokerage closures | Brokerage mergers | Analyst terminations |

| 1988 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1994 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1997 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1998 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 1999 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2000 | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| 2001 | 2 | 11 | 13 |

| 2002 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 2003 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2004 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2005 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 2006 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2007 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 2008 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2010 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2011 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2012 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2013 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 22 | 36 | 58 |

- Note: This table reports the annual distribution of a total of 58 analyst termination events, including 22 brokerage closures and 36 brokerage mergers.

We exclude firms in the utilities and financial industries and require each firm-year observation to have at least one analyst following, a minimum of $1 million in total assets, and nonnegative total sales. Table 2 provides the summary statistics of all variables used in the main analyses. To mitigate the effect of outliers, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The mean value of ABS_DA is 0.062, comparable to previous studies. The mean value of Restatement is 0.052, indicating that about 5% of our sample experiences an accounting restatement. Competition has an average of −0.198 across all firms, and Treat has a mean value of 0.026, indicating about 2270 out of a total of 87,310 firm-year observations in our sample experience an analyst termination event.

| N | Mean | Std. Dev | p25 | Median | p75 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main variables | ||||||

| ABS_DA | 87,310 | 0.062 | 0.079 | 0.016 | 0.037 | 0.076 |

| Restatement | 45,626 | 0.052 | 0.222 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Competition | 87,310 | −0.198 | 0.169 | −0.255 | −0.143 | −0.082 |

| Treat | 87,310 | 0.026 | 0.124 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Ln (Assets) | 87,310 | 5.608 | 2.191 | 3.937 | 5.488 | 7.132 |

| MTB | 87,310 | 1.920 | 1.524 | 1.046 | 1.420 | 2.158 |

| Leverage | 87,310 | 0.175 | 0.192 | 0.003 | 0.122 | 0.283 |

| ROA | 87,310 | 0.073 | 0.109 | 0.041 | 0.108 | 0.166 |

| Asset Growth | 87,310 | 0.130 | 0.388 | −0.043 | 0.053 | 0.186 |

| Cash Flow Volatility | 87,310 | 0.091 | 0.136 | 0.019 | 0.042 | 0.099 |

| Additional variables | ||||||

| Entropy Balanced DA | 87,310 | 0.053 | 0.063 | 0.013 | 0.032 | 0.069 |

| Discretionary Current Accruals | 87,310 | 0.049 | 0.062 | 0.009 | 0.028 | 0.065 |

| AAER | 87,310 | 0.021 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Competition_Census | 87,310 | −0.109 | 0.150 | −0.118 | −0.065 | −0.011 |

| TotalSimilarity | 78,789 | 3.350 | 5.719 | 1.075 | 1.435 | 3.036 |

| Product Fluidity | 78,013 | 6.586 | 3.377 | 4.164 | 6.001 | 8.354 |

| RM | 87,310 | 0.291 | 0.287 | 0.082 | 0.197 | 0.406 |

- Note: This table reports descriptive statistics for the variables used in our analyses. Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. All continuous variables are winsorized at 1% and 99% level.

- Abbreviations: AAER, Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release; ROA, return on assets.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

4.1 Main results

We report our baseline DDD regression results from estimating equation (1) in Table 3. Panel A uses a continuous Competition measure, and Panel B converts the continuous Competition into a binary indicator, Competition_High. In Column (1) of Panel A, we use ABS_DA as the dependent variable and find that the coefficient on Treat is positive and statistically significant, indicating that earnings management increases when analyst coverage decreases.9 We find that the coefficient on Competition is not statistically significant. In Column (2), we add the interaction between Treat and Competition into the regression and find that Treat × Competition loads significantly positive at 1%. The economic significance is also meaningful: A one standard deviation increase in Competition is associated with a 0.039 × 0.169 = 0.66 percentage point or 8.3 (0.66%/0.079 = 0.083) percentage increase in discretionary accruals. This finding suggests a greater increase in earnings management following the reduction of analyst coverage as competition intensifies. In Columns (3) and (4), we switch the dependent variable to Restatement and repeat our analyses. Column (3) shows a similar effect to Column (1): financial restatements increase when analyst coverage decreases. In Column (4), where the interaction between Treat and Competition is included, we find that the coefficient on Treat × Competition is significantly positive at 1%. A one standard deviation increase in Competition is associated with a 0.189 × 0.169 = 3.19 percentage point or 14.4 (0.0139/0.222 = 0.144) percentage increase in restatements after analyst coverage reduces. This suggests that the impact of the reduction in analyst coverage on financial restatement exacerbates as competition intensifies. Thus, hypothesis H1a on the governance effect of competition on financial misreporting is rejected, and hypothesis H1b on the dark side of competition is supported.

| Panel A: Continuous competition measure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | ABS_DA | Restatement | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.005** | 0.011*** | 0.046*** | 0.076*** |

| (2.51) | (3.53) | (3.83) | (4.11) | |

| Competition | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.026 |

| (0.74) | (0.68) | (1.26) | (1.23) | |

| TreatCompetition | 0.039*** | 0.189** | ||

| (3.96) | (2.30) | |||

| ROA | −0.085*** | −0.085*** | −0.043*** | −0.043*** |

| (−18.42) | (−18.42) | (−3.49) | (−3.49) | |

| MB | 0.002*** | 0.002*** | −0.002* | −0.002* |

| (5.69) | (5.70) | (−1.72) | (−1.68) | |

| Leverage | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.024* | 0.024* |

| (−0.54) | (−0.55) | (1.96) | (1.94) | |

| Asset Growth | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0.017*** | 0.017*** |

| (−1.45) | (−1.45) | (4.10) | (4.11) | |

| Cash Flow Volatility | 0.194*** | 0.194*** | 0.052*** | 0.052*** |

| (32.21) | (32.22) | (3.63) | (3.61) | |

| Ln (Assets) | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.012*** | 0.012*** |

| (−1.32) | (−1.32) | (4.02) | (4.03) | |

| Observations | 87,310 | 87,310 | 45,626 | 45,626 |

| R2 | 0.371 | 0.371 | 0.045 | 0.045 |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Panel B: Binary Competition measure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | ABS_DA | Restatement | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.005** | 0.009*** | 0.046*** | 0.075*** |

| (2.52) | (3.05) | (3.84) | (4.75) | |

| Competition_High | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.005 | −0.006 |

| (−1.01) | (−1.17) | (−0.74) | (−0.93) | |

| Treat Competition_High | 0.011*** | 0.085*** | ||

| (3.07) | (3.95) | |||

| ROA | −0.085*** | −0.085*** | −0.043*** | −0.043*** |

| (−18.41) | (−18.41) | (−3.49) | (−3.47) | |

| MB | 0.002*** | 0.002*** | −0.002* | −0.002* |

| (5.70) | (5.71) | (−1.71) | (−1.65) | |

| Leverage | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.024** | 0.024* |

| (−0.53) | (−0.53) | (1.97) | (1.95) | |

| Asset Growth | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.017*** | 0.017*** |

| (−1.46) | (−1.47) | (4.06) | (4.05) | |

| Cash Flow Volatility | 0.194*** | 0.194*** | 0.053*** | 0.052*** |

| (32.21) | (32.22) | (3.67) | (3.65) | |

| Ln (Assets) | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.012*** | 0.012*** |

| (−1.25) | (−1.25) | (4.13) | (4.15) | |

| Observations | 87,310 | 87,310 | 45,626 | 45,626 |

| R2 | 0.371 | 0.371 | 0.044 | 0.044 |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Panel C: Reverse causality | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | Restatement |

| Treat Year (−1) | −0.002 | −0.004 |

| (−0.96) | (−0.27) | |

| Treat Year (0) | 0.006*** | 0.080*** |

| (3.48) | (3.57) | |

| Treat Year (1) | −0.002 | 0.003 |

| (−1.29) | (0.23) | |

| Treat Year (2+) | −0.003 | −0.019 |

| (−1.52) | (−1.46) | |

| Treat Year (−1) Competition | −0.002 | 0.020 |

| (−0.21) | (0.31) | |

| Treat Year (0) Competition | 0.045*** | 0.183** |

| (2.91) | (1.99) | |

| Treat Year (1) Competition | −0.007 | 0.011 |

| (−0.98) | (0.16) | |

| Treat Year (2+) Competition | −0.003 | −0.049 |

| (−0.57) | (−0.76) | |

| Competition | 0.004 | 0.025 |

| (1.05) | (0.92) | |

| ROA | −0.038*** | −0.060*** |

| (−9.84) | (−3.51) | |

| MB | 0.002*** | −0.004*** |

| (5.87) | (−2.60) | |

| Leverage | −0.008*** | 0.019 |

| (−2.93) | (1.12) | |

| Asset Growth | 0.015*** | 0.021*** |

| (14.20) | (3.82) | |

| Cash Flow Volatility | 0.057*** | 0.041** |

| (12.09) | (2.09) | |

| Ln (Assets) | −0.005*** | 0.015*** |

| (−6.88) | (3.87) | |

| Observations | 57,242 | 32,633 |

| R2 | 0.391 | 0.054 |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the regression results of equation (1). Panel A uses a continuous measure of Competition, and Panel B uses a binary competitive industry indicator, Competition_High. Panel C replaces Treat with four treatment-year indicators. Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. T-statistics in parentheses and corresponding p values are calculated using standard errors clustered by firm and year. *, ** and *** indicate p values that are significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviation: ROA, return on assets.

In Panel B, we create a Competition_High indicator to capture competitive industries with a Competition above the sample median and find very similar results to those in Panel A. In particular, the significant and positive coefficients on Treat × Competition_High in Panel B show that relative to noncompetitive industries (i.e., Competition_High = 0), competitive industries (i.e., Competition_High = 1) experience larger increases in both earnings management and accounting restatements when analyst coverage reduces. In summary, the results in Table 3 reject H1a and support H1b. They provide evidence that the increase in earnings management and restatements is higher in more competitive industries when analyst coverage decreases. These findings are consistent with the argument that product market competition exacerbates financial misreporting when corporate governance weakens.

4.2 Reverse causality

Although the inclusion of firm- and year-fixed effects in equation (1) alleviates concerns of time-invariant omitted variable bias, another threat to our preferable interpretation is reverse causality or the “selection effect” story. That is, a higher likelihood of financial misreporting tends to occur in competitive industries, leading to endogenous brokerage closure or merger decisions.10 To address this issue, we follow Bertrand and Mullainathan (2003) and replace the Treat dummy in equation (1) with four dummies: Treat Year (−1), Treat Year (0), Treat Year (1) and Treat Year (2+). Treat Year (−1) is a dummy that takes the value of one if a firm experiences a brokerage closure or merger 1 year from now. Similarly, Treat Year (0), Treat Year (1) and Treat Year (2+) take the value of one if a firm experiences a brokerage closure or merger in the current year, 1 year ago and 2 or more years ago, respectively. If analyst terminations were a response to more financial misreporting in competitive industries, we would expect to observe an “effect” before the treatment year. In other words, a positive and significant coefficient on Treat Year (−1) Competition would indicate reverse causality.

As is demonstrated in Table 3 Panel C, the coefficient on Treat Year (−1) Competition is virtually zero and statistically insignificant, which suggests that reverse causality is not a concern and supports the causal interpretation of our results. We also note two important observations. First, the effect of the terminations mostly concentrates in the treatment year, suggesting that firms in competitive industries immediately begin to manipulate earnings when an equilibrium of analyst monitoring is disrupted. Second, consistent with the observation that treatment firms typically regain their analyst coverage within 3 years of the event (Chen et al., 2015; Derrien & Kecskés, 2013), we do not detect a significant coefficient on Treat Year (1) Competition or Treat Year (2+) Competition. These two observations highlight the immediate effect of the competitive pressure on firms’ financial misreporting decisions when they experience a loss in the monitoring channel and speak to the value of our study.

4.3 Monitoring channel

The above results indicate that the loss of a governance monitoring channel, such as analyst coverage, is more detrimental in highly competitive industries where managers face substantial competitive pressure to deliver satisfying financial performance. To further substantiate this finding, we conduct a set of cross-sectional analyses consisting of three partitions along the monitoring channel.

Our first partition compares firms with high versus low initial analyst coverage. Chen et al. (2015) found that the effect of the reduction in analyst coverage is greater in firms with initially low analyst coverage, where losing an individual analyst is more significant. Along this line, we expect the loss of analyst coverage to have a more pronounced effect on the relationship between competition and financial misreporting in firms with lower initial analyst coverage. To test this prediction, we split the sample into high and low initial analyst coverage subsamples by the treatment sample's median value 1 year before brokerage closures and mergers.11 We rerun equation (1) and report the cross-sectional results in Table 4 Panel A. We find that the coefficient on Treat × Competition is significantly positive in the low initial analyst coverage subsample in Columns (1) and (3), using both measures of financial reporting quality, but statistically insignificant in Columns (2) and (4), the high initial analyst coverage subsample. When we compare the coefficients on Treat × Competition cross-sectionally, we find that the difference is statistically significant at 1% (10%) for the earnings management (accounting restatement) regressions. These findings suggest that our main results are mostly driven by firms with low initial analyst coverage, which supports the notion that losing a monitoring channel such as analyst coverage is particularly important for competitive industries in reducing financial misreporting.

| Panel A: High vs. low initial analyst coverage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Low initial analyst coverage | High initial analyst coverage | Low initial analyst coverage | High initial analyst coverage | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | ABS_DA | Restatement | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.020*** | 0.002 | 0.117*** | 0.016 |

| (2.94) | (1.22) | (2.86) | (1.06) | |

| Competition | −0.004 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.035 |

| (−0.52) | (0.51) | (0.43) | (1.45) | |

| TreatCompetition | 0.075*** | 0.004 | 0.199*** | 0.036 |

| (3.33) | (0.68) | (2.79) | (0.13) | |

| Observations | 43,394 | 43,916 | 16,852 | 28,774 |

| R2 | 0.439 | 0.283 | 0.056 | 0.035 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test for equality of the interaction terms across subsamples: | ||||

| p = 0.001 | p = 0.054 | |||

| Panel B: Dropping high vs. low-quality analysts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Dropping high quality analysts | Dropping low quality analysts | Dropping high quality analysts | Dropping low quality analysts | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | ABS_DA | Restatement | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.012*** | 0.006 | 0.081*** | 0.030 |

| (3.40) | (1.02) | (3.72) | (0.71) | |

| Competition | −0.003 | 0.008** | 0.037 | 0.040 |

| (−0.54) | (2.06) | (1.26) | (1.12) | |

| Treat Competition | 0.065*** | 0.018 | 0.215** | 0.024 |

| (4.50) | (0.98) | (2.14) | (0.14) | |

| Observations | 36,227 | 51,083 | 18,212 | 27,414 |

| R2 | 0.416 | 0.361 | 0.067 | 0.045 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test for equality of the interaction terms across subsamples: | ||||

| p = 0.025 | p = 0.001 | |||

| Panel C: High vs. Low Institutional Ownership | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Low institutional ownership | High institutional ownership | Low institutional ownership | High institutional ownership | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | ABS_DA | Restatement | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.028 | 0.035 |

| (1.62) | (1.30) | (1.45) | (1.43) | |

| Competition | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.047 | 0.016 |

| (0.27) | (0.84) | (1.44) | (0.39) | |

| Treat Competition | 0.058** | 0.003 | 0.221** | -0.024 |

| (2.12) | (0.44) | (2.55) | (−0.19) | |

| Observations | 34,644 | 35,148 | 18,007 | 18,413 |

| R2 | 0.395 | 0.289 | 0.064 | 0.029 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test for equality of the interaction terms across subsamples: | ||||

| p = 0.028 | p = 0.035 | |||

- Note: This table reports the results of cross-sectional analyses of equation (1) by monitoring strength. Panels A, B and C split the sample into high and low initial analyst coverage, quality analysts and institutional ownership subsamples, respectively, based on the sample median 1 year before brokerage mergers. Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. T-statistics in parentheses and corresponding p values are calculated using standard errors clustered by firm and year. *, ** and *** indicate p values that are significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

Our second partition compares firms dropping high- versus low-quality analysts due to brokerage closures and mergers. Yu (2008) documented that analysts serve as a strong monitor in discouraging earnings management, as they track corporate disclosures on a regular basis and have substantial financial knowledge and industry background. They also exert a monitoring effect on managers by directly interacting with them during earnings announcements and conference calls. We expect the loss of analyst coverage to have a more pronounced effect on the relationship between competition and financial reporting quality in firms dropping higher-quality analysts. Following Derrien and Kecskés (2013), we calculate analyst quality using the broker's relative earnings forecast accuracy.

We partition our sample into high- and low-quality analysts subsamples based on sample median and rerun equation (1). Table 4 Panel B shows the results. Consistent with our prediction, the coefficients on Treat × Competition are significant and positive in firms dropping high-quality analysts in Columns (1) and (3) but statistically indistinguishable from zero in firms dropping low-quality analysts in Columns (2) and (4). These findings suggest that the effect of competition on financial reporting quality is more pronounced in firms losing high-quality analysts following analyst terminations, reinforcing our argument that analysts exert more monitoring effect in reducing financial misreporting in competitive (vs. noncompetitive) industries.

Our third partition is based on institutional ownership. Institutional investors are another commonly studied corporate governance mechanism that disciplines managers and improves financial reporting quality (Graham et al., 2005; Ramalingegowda & Yu, 2012). We expect a reduction in analyst coverage to have a more substantial impact on the relationship between competition and financial misreporting when firms have lower institutional ownership, thus less outside scrutiny. To test this prediction, we partition our samples into high and low institutional ownership subsamples based on the sample median. We rerun equation (1) and present the cross-sectional analyses in Table 4 Panel C. We find that our main result concentrates in the low institutional ownership subsample. The coefficients on Treat × Competition are significantly positive in Columns (1) and (3) for firms with low institutional ownership but not in Columns (2) and (4) for firms with high institutional ownership, and the cross-sectional difference is significant at the 5% level for both ABS_DA and Restatement measures, consistent with our prediction that when corporate governance is weaker, the loss of analyst coverage is more damaging in the context of financial misreporting to competitive than noncompetitive firms. In summary, the results in Table 4 bolster our monitoring channel argument: Product market competition creates pressure for managers to misreport earnings, and the monitoring effect from analysts in curtailing this opportunistic behavior is more significant in competitive industries.

4.4 Financial constraints

Next, we examine to what extent the effect of analyst coverage on the relationship between competition and financial reporting quality depends on financial constraints. We reason that firms facing financial constraints are more likely to manipulate earnings to signal positive prospects and ease funding constraints. The combined pressure from financial constraints and competition may incentivize earnings manipulation when analyst coverage is reduced. This implies that we should observe a stronger effect of our main findings in financially constrained firms.

To test this prediction, we divide our sample into financially constrained and unconstrained firms using two common measures of financial constraints following prior literature: the HP Index (Hadlock & Pierce, 2010) and the WW Index (Whited & Wu, 2006). We define a firm as financially constrained if its HP Index (WW Index) is below (above) the sample median and reestimate Equation (1) across the subsamples. Table 5 presents the results, with Panel A using the HP Index and Panel B the WW Index. In both panels, we find that the coefficients on Treat × Competition are significantly positive in the financially constrained subsample but not in the financially unconstrained subsample. This suggests that following the reduction of analyst coverage, competitive firms are more likely than noncompetitive firms to misreport earnings when they are financially constrained. When we compare the cross-sectional difference in the coefficients, we observe that the coefficients on Treat × Competition are significantly more positive in the financially constrained subsample using both proxies of financial misreporting across both panels of the financial constraint measures. Collectively, evidence in Table 5 corroborates our finding that competitive firms are more likely to manipulate earnings when corporate governance is weaker because managers are under greater pressure to deliver strong financial performance.

| Panel A: HP Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Financially constrained firms | Financially unconstrained firms | Financially constrained firms | Financially unconstrained firms | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | ABS_DA | Restatement | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.008*** | 0.005 | 0.081*** | 0.044 |

| (4.65) | (1.46) | (3.86) | (1.22) | |

| Competition | 0.000 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.089** |

| (0.11) | (1.32) | (−0.07) | (2.47) | |

| Treat Competition | 0.050*** | −0.000 | 0.229*** | 0.002 |

| (4.26) | (−0.02) | (3.11) | (0.01) | |

| Observations | 43,655 | 43,655 | 21,835 | 23,791 |

| R2 | 0.380 | 0.352 | 0.049 | 0.041 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test for equality of the interaction terms across subsamples: | ||||

| p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | |||

| Panel B: WW Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Financially constrained firms | Financially unconstrained firms | Financially constrained firms | Financially unconstrained firms | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | ABS_DA | Restatement | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.008*** | 0.003 | 0.040** | −0.008 |

| (3.95) | (0.80) | (2.44) | (−0.23) | |

| Competition | -0.000 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.089** |

| (−0.04) | (0.86) | (0.52) | (2.15) | |

| Treat Competition | 0.053*** | −0.003 | 0.237*** | −0.144 |

| (3.51) | (−0.18) | (2.74) | (−0.75) | |

| Observations | 35,807 | 35,799 | 17,898 | 19,473 |

| R2 | 0.474 | 0.204 | 0.050 | 0.040 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F-test for equality of the interaction terms across subsamples: | ||||

| p = 0.012 | p = 0.001 | |||

- Note: This table reports the results of cross-sectional analyses of equation (1) by financial constraints. Panels A and B proxy for financial constraints using the Hadlock and Pierce (2010) index, HP Index and the Whited and Wu (2006) index, WW index, respectively. Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. T-statistics in parentheses and corresponding p values are calculated using standard errors clustered by firm and year. *, ** and *** indicate p values that are significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

5 ROBUSTNESS TESTS AND ADDITIONAL ANALYSES

5.1 Alternative variable measures

We conduct several robustness tests to ensure our results withstand different empirical specifications in this section. First, we perform robustness tests using alternative measures of financial reporting quality, which include entropy-balanced discretionary accruals, discretionary current accruals, AAER enforcement actions and signed discretionary accruals. We calculate Entropy Balanced DA following McMullin and Schonberger (2020), which illustrates that entropy-balanced accruals significantly reduce biases relative to linear accrual process and are superior to propensity-score matched models in detecting accruals manipulation. The discretionary current accruals are from Teoh et al. (1998), who find that managers have more discretion over short-term discretionary accruals. We calculate Discretionary Current Accruals as the current working capital accruals adjusted by industry means. AAER enforcement actions represent more severe cases of financial misreporting identified by the SEC, and we set AAER to equal one if the SEC identifies an accounting fraud or misrepresentation for a firm during the year and zero otherwise. Table 6 Panel A illustrates the results using these alternative measures. We continue to find a significantly positive coefficient on Treat × Competition across all alternative measures, consistent with our baseline regression results.12

| Panel A: Alternative measures of financial reporting quality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| D. V.= | Entropy Balanced DA | Discretionary Current Accruals | AAER |

| Treat | 0.011*** | 0.007*** | 0.053*** |

| (3.46) | (4.56) | (4.84) | |

| Competition | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| (1.01) | (0.80) | (1.01) | |

| Treat X Competition | 0.038*** | 0.025*** | 0.139*** |

| (3.90) | (3.64) | (3.00) | |

| Observations | 87,310 | 87,310 | 87,310 |

| R2 | 0.391 | 0.401 | 0.121 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Panel B: Alternative measures of product market competition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | Restatement | ABS_DA | Restatement | ABS_DA | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.000 | 0.021 | −0.007 | −0.008 | 0.007*** | 0.057*** |

| (0.11) | (1.30) | (−1.42) | (−0.28) | (2.73) | (3.43) | |

| Total_Similarity | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| (1.15) | (0.05) | |||||

| Treat Total_Similarity | 0.001** | 0.006*** | ||||

| (2.34) | (2.85) | |||||

| Product_Fluidity | 0.000* | −0.000 | ||||

| (1.83) | (−0.19) | |||||

| Treat Product_Fluidity | 0.002* | 0.008** | ||||

| (1.91) | (2.53) | |||||

| Competition_Census | 0.001 | 0.019 | ||||

| (0.48) | (1.44) | |||||

| Treat ompetition_Census | 0.019** | 0.114* | ||||

| (2.05) | (1.76) | |||||

| Observations | 78,789 | 39,814 | 78,013 | 39,527 | 87,310 | 45,626 |

| R2 | 0.446 | 0.042 | 0.447 | 0.041 | 0.371 | 0.043 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the regression results of equation (1), estimated using alternative measures of financial reporting quality and product market competition in Panels A and B, respectively. Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. T-statistics in parentheses and corresponding p values are calculated using standard errors clustered by firm and year. *, ** and *** indicate p values that are significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

Second, we rerun Equation (1) using three alternative measures of product market competition. TotalSimilarity is a firm-by-firm pairwise similarity score by parsing the product descriptions from the firm 10-Ks used in Hoberg and Phillips (2016). ProductFluidity is a firm-level measure capturing the degree to which changes in rival firms’ product descriptions in the 10-K relative to a firm's products used in Hoberg et al. (2014). TotalSimilarity and ProductFluidity address the concerns that Competition is an industry-level measure and may only capture some form of competition. Competition_Census is the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index calculated based on a Census Survey that covers private and public firms. In Panel B of Table 6, we report the regression results of equation (1) using these alternative competition measures. In all columns where higher values of TotalSimilarity, ProductFluidity and Competition_Census capture more competition, we find significantly positive coefficients on TreatTotalSimilarity, Treat ProductFluidity and Treat Competition_Census using both discretionary accruals and restatement as the dependent variable. Taken together, we find robust results using alternative competition measures.

5.2 Alternative model specifications

Next, we conduct two analyses to confirm that our results are not sensitive to model specifications. First, we replace the year-fixed effects in equation (1) with industry-by-year fixed effects to allow for time-varying industry trends. This alternative specification eliminates the possibility that our results might be driven by shocks at the industry level that affect firms’ incentives to misreport financial statements. We present the results in Table 7 Panel A and confirm that our results remain unchanged.13 Second, we remove all control variables from equation (1) because the inclusion of control variables in a regression should not change the treatment effect if the shocks are likely to be exogenous. In Panel B, we show the results after removing all control variables and only keeping firm- and year-fixed effects. Results in both columns are statistically significant. In summary, Table 7 shows that our findings are not sensitive to model specifications.

| Panel A: Industry-by-year fixed effects | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.011*** | 0.102*** |

| (3.11) | (5.16) | |

| Treat Competition | 0.036*** | 0.386*** |

| (2.93) | (4.32) | |

| ROA | −0.080*** | −0.036*** |

| (−16.58) | (−2.79) | |

| MB | 0.002*** | −0.002 |

| (4.89) | (−1.63) | |

| Leverage | −0.001 | 0.019 |

| (−0.37) | (1.54) | |

| Assets Growth | -0.000 | 0.018*** |

| (−0.39) | (4.29) | |

| Cash Flow Volatility | 0.195*** | 0.047*** |

| (31.57) | (3.13) | |

| Ln (Assets) | −0.002** | 0.011*** |

| (−2.20) | (3.48) | |

| Observations | 87,310 | 45,626 |

| R2 | 0.382 | 0.059 |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Industry-Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Panel B: Removing “Bad” Controls | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| D. V.= | ABS_DA | Restatement |

| Treat | 0.012*** | 0.077*** |

| (3.45) | (4.15) | |

| Competition | −0.002 | 0.029 |

| (−0.46) | (1.40) | |

| Treat Competition | 0.043*** | 0.191** |

| (4.10) | (2.32) | |

| Observations | 87,310 | 45,626 |

| R2 | 0.277 | 0.043 |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the regression results of equation (1) using alternative model specifications. Panel A replaces year-fixed effects with industry-by-year fixed effects, and Panel B removes all control variables from equation (1). Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. T-statistics in parentheses and corresponding p values are calculated using standard errors clustered by firm and year. *, ** and *** indicate p values that are significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviation: ROA, return on assets.

5.3 Additional analyses—managerial expropriation and slack

Our main argument is that whether competition exerts a disciplining or damaging effect on managerial behavior depends on the specific form of the agency problem. While our study primarily focuses on financial misreporting and shows that competition produces a damaging effect when analyst monitoring weakens, we revisit two prior studies on managerial expropriation and managerial slack to illustrate that competition can simultaneously induce a disciplining effect by reducing certain managerial misbehavior. We revisit Chen et al. (2015) using CEO compensation and Giroud and Mueller (2010) using ROA. Our results are consistent with those studies and show that competition can mitigate the managerial expropriation type of agency conflict as well as managerial slack. Detailed analyses and results are presented in Appendix B.

5.4 Additional analysis—real activities management

In this final section, we perform additional analysis to check whether our findings also apply to real activities management. Unlike accruals management, which manipulates accounting accruals, real activities management involves manipulating operational activities. Examples of real activities management include cutting discretionary expenditures and overproduction to reduce the cost of goods sold. Research finds that firms facing pressure to meet earnings expectations engage in real activities management (Graham et al., 2005; Roychowdhury, 2006), but because real activities management deviates from optimal operational decisions and hurts a firm's long-term performance, it is constrained by industry competition, among other factors (Shi et al., 2018; Zang, 2012).

It is ex-ante unclear whether firms in competitive industries are more or less likely to manage real activities when governance monitoring weakens. On the one hand, survey evidence suggests that executives are willing to sacrifice long-term value when facing short-term earnings pressures (Graham et al., 2005), suggesting that firms facing more competitive pressure from industry peers might conduct more real activities management when analyst coverage reduces. On the other hand, because real activities management negatively impacts a firm's future performance, impairing its competitive status against industry rivals, firms in competitive industries might conduct fewer real activities management than noncompetitive industries when analyst coverage reduces.

We follow Roychowdhury (2006) and calculate the total amount of real activities management, RM, and rerun equation (1) with RM as the dependent variable. Results are presented in Table 8. Column (1) of Table 8 reports a significantly positive coefficient on Treat, suggesting that when analyst coverage decreases, real activities management, on average, increases. We do not find a significant coefficient on Competition, suggesting that competitive industries do not seem to engage in more real activities management relative to noncompetitive industries, on average. In Column (2), we include TreatCompetition and do not find a statistical significance, indicating that there is no significant difference in engagement in real activities management in competitive industries relative to noncompetitive industries after analyst coverage decreases. Overall, evidence suggests that the main effect we document on financial misreporting does not transfer to real activities management, and firms in competitive industries do not manage real activities more or less than those in noncompetitive industries when governance monitoring weakens.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| D. V.= | RM | RM |

| Treat | 0.014*** | 0.015** |

| (3.34) | (2.39) | |

| Competition | 0.002 | −0.002 |

| (0.12) | (−0.12) | |

| TreatCompetition | 0.003 | |

| (0.13) | ||

| Observations | 87,310 | 87,310 |

| R2 | 0.764 | 0.764 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the regression results of equation (1) using real activities management as the dependent variable. Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. T-statistics in parentheses and corresponding p values are calculated using standard errors clustered by firm and year. *, ** and *** indicate p values that are significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

6 CONCLUSION

This paper shows that firms in competitive industries engage in more financial misreporting than noncompetitive industries when analyst coverage exogenously reduces. This finding holds across various alternative measures of financial misreporting and product market competition and is robust in different model specifications. In addition, we document that the effect is stronger in firms where analyst coverage is more important and when firms experience financial constraints. We interpret these findings as evidence that illustrates the dark side of competition: competitive pressure incentivizes managers to misreport financial statements when analyst monitoring is weaker.

We also revisit prior studies and show that managerial slack increases more for firms in noncompetitive versus competitive industries after analyst coverage reduces, demonstrating the disciplinary side of competition. Our study highlights the multifaceted manifestations of managerial misbehavior in an agency context and offers a reconciliation of two streams of studies that reach seemingly contradictory conclusions about competition's role in corporate governance. We advocate that competition cannot be simply viewed as a “good” or “bad” corporate governance mechanism. Overall, our paper shows that competition can curb managerial slack and simultaneously encourage financial misreporting when analyst monitoring weakens. This finding offers important policy implications for regulators and corporate stakeholders in designing corporate governance structures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewer and the editor from Journal of Business Finance and Accounting for their constructive comments.

APPENDIX A: VARIABLE DEFINITION

| Variable | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Main variables | ||

| ABS_DA | The absolute value of discretionary accruals is calculated using the modified Jones model controlling for performance. | Compustat |

| Restatement | An indicator variable that equals one if a firm restates year t’s annual statement and zero otherwise | Audit analytics |

| Competition | The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, calculated as the sum of the squared market share of sales for all firms in an industry (3-digit SIC) in a year multiplied by minus one | Compustat |

| Competition_High | An indicator variable that equals one if an industry has a Competition greater than the sample median and zero otherwise | Compustat |

| Treat | An indicator variable that equals one if a firm experiences a brokerage closure or merger by the year and zero otherwise | Hand collected |

| Control variables | ||

| Ln (Assets) | The natural logarithm of total assets | Compustat |

| MTB | Total assets, less book value of equity, plus market value of equity, scaled by total assets | Compustat |

| ROA | Income before extraordinary items, scaled by total assets | Compustat |

| Asset Growth | Change in total assets from year t-1 to t | Compustat |

| Leverage | The ratio of the book value of long-term debt to the lagged book value of total assets | Compustat |

| Cash Flow Volatility | The ratio of the standard deviation of the past eight earnings changes to the average book assets size over the past eight quarters | Compustat |

| Cross-sectional variables | ||

| Initial Analyst Coverage | The number of analysts covering a firm one year before a brokerage merger | I/B/E/S |

| Analyst Quality | The broker's relative earnings forecast accuracy following Derrien and Kecskés (2013). First, we calculate the earnings forecast accuracy for each analyst as the absolute difference between analyst forecasted earnings per share and the actual earnings, scaled by the beginning-of-quarter price for each analyst before brokerage mergers. We then rank all analysts covering the same firm, on a scale of zero to one, based on their earnings forecast accuracy. For each broker, we calculate the mean accuracy rank, on a scale of zero to one, across all firms its analysts cover as our measure of analyst quality | I/B/E/S |

| Institutional Ownership | The average quarterly institutional ownership within a year | Thompson Reuters 13F |

| HP Index |

The Hadlock and Pierce (2010) financial constraint index, calculated as

where Ln (Asset) is the natural logarithm of total assets and Age is the number of years since the inception date in Compustat |

Compustat |

| WW Index |

The Whited and Wu (2006) financial constraint index, calculated as

where is the ratio of operating cash flow to total assets, is an indicator of cash dividends in a year, is the industry sales growth based on 3-digit SIC code, and is the firm-level sales growth |

Compustat |

| Alternative measures | ||

| Entropy Balanced DA |

Entropy-balanced discretionary accruals following McMullin and Schonberger (2020):

where Accruals is total accruals, Treat is previously defined, and X is a vector of accruals determinants used the modified Jones model (Log_AT, PPE, ΔREV and ROA) |

Compustat |

| Discretionary Current Accruals | Current working capital accruals adjusted by industry mean following Teoh et al. (1998) | Compustat |

| AAER | An indicator variable that equals one if the SEC identifies an accounting fraud or misrepresentation for a firm during the year and zero otherwise | AAER |

| Positive DA | The absolute value of positive discretionary accrual calculated using the modified Jones model controlling for performance | Compustat |

| Negative DA | The absolute value of negative discretionary accrual, calculated using the modified Jones model controlling for performance | Compustat |

| Competition_Census | The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, calculated as the sum of the squared market share of sales for all firms in an industry (3-digit SIC) based on Census Survey in a year multiplied by minus one | Census Survey and Hand collected |

| Total_Similarity | Firm-by-firm pairwise similarity scores by parsing the product descriptions from the firm 10°Ks from Hoberg and Philips (2016) | Hoberg and Philips website |

| Product_Fluidity | The degree to which changes in rival firms’ product descriptions in the 10-K relative to a firm's products from Hoberg, et al. (2014) | Hoberg and Philips website |

| Additional variables | ||

| Treat Year (−1) | An indicator variable that equals one if a firm experiences a brokerage closure or merger one year from now and zero otherwise | Hand collected |

| Treat Year (0) | An indicator variable that equals one if a firm experiences a brokerage closure or merge in the current year and zero otherwise | Hand collected |

| Treat Year (1) | An indicator variable that equals one if a firm experiences a brokerage closure or merge one year ago and zero otherwise | Hand collected |

| Treat Year (2+) | An indicator variable that equals one if a firm experiences a brokerage closure or merge two or more years ago and zero otherwise | Hand collected |

| Ln (Total Compensation) | The natural logarithm of a CEO's total compensation from salary, bonus, stocks, options and any other annual pay | ExecuComp |

| Excess Compensation | The CEO's excess compensation, calculated as the residuals from regressing CEO total compensation on firms’ total market value following Chen et al. (2015) | ExecuComp |

| RM | Total amount of real activities management from abnormal cash flows from operations, abnormal production costs and discretionary expenditures estimated for each firm-year following Roychowdhury (2006). We multiply the residuals of discretionary expenditures and abnormal cash flows from operations by −1 | Compustat |

APPENDIX B: ADDITIONAL ANALYSES—MANAGERIAL EXPROPRIATION AND SLACK

Although our main results primarily focus on financial misreporting and illustrate that competition produces a damaging effect when analyst monitoring weakens, in this section, we revisit two prior studies on managerial expropriation and managerial slack to illustrate that competition can simultaneously induce a disciplining effect by reducing certain managerial misbehavior. First, we revisit Chen et al. (2015) using CEO compensation. Employing the same analyst termination research setting, the authors find that managers extract excess compensation (and more private benefits in total) after a reduction in analyst monitoring, and the effect is more severe in noncompetitive industries. Along with similar results from cash holdings and value-destroying acquisitions, Chen et al. (2015) concluded that analyst coverage mitigates managerial expropriation of shareholders, and that competition substitutes this monitoring effect.14

To measure Total Compensation, we add a CEO's total compensation from salary, bonus, stocks, options and any other annual pay and take the natural logarithm. Excess compensation is calculated as the residuals from regressing CEO total compensation on firms’ total market value, following Chen et al. (2015). We report the results in Table B.1 Panel A.15 When we follow Chen et al. (2015) and partition the sample into less and more product market competition based on the HHI industry median, we find the effect of termination of analyst coverage has differential impact along the competition dimension. The coefficient of Treat dummy is highly positive and significant in all models, showing an increase in managerial compensation after analyst termination. However, the interaction term, Treat Competition_High, is negative and significant across Columns (2) and (4) for both Total Compensation and Excess Compensation, suggesting that CEO total and excess compensation increase less in competitive industries after analyst terminations. These findings show that competition can mitigate the managerial expropriation type of agency conflict, which is consistent with Chen et al. (2015).

| Panel A: Managerial Compensation (Chen et al., 2015) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| D. V.= | Ln (total Compensation) | Ln (total Compensation) | Excess Compensation | Excess Compensation |

| Treat | 0.229** | 0.544*** | 0.200** | 0.408*** |

| (2.21) | (3.55) | (2.11) | (2.66) | |

| Competition_High | 0.018 | 0.028 | −0.036 | −0.029 |

| (0.34) | (0.53) | (−0.79) | (−0.64) | |

| Treat Competition_High | −0.561*** | −0.392** | ||

| (−2.84) | (−1.97) | |||

| Observations | 11,756 | 11,756 | 11,756 | 11,756 |

| R2 | 0.485 | 0.485 | 0.493 | 0.493 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Panel B: ROA (Giroud & Mueller, 2010) | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| D. V.= | ROA | ROA |

| Treat | −0.002*** | −0.001 |

| (−2.94) | (−0.57) | |

| TreatCompetition | 0.019** | |

| (2.08) | ||

| Observations | 77,211 | 77,211 |

| R2 | 0.719 | 0.719 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table reports the regression results of equation (1) using CEO compensation and ROA as the dependent variable in Panels A and B, respectively. Detailed variable definitions are listed in Appendix A. T-statistics in parentheses and corresponding p values are calculated using standard errors clustered by firm and year. *, ** and *** indicate p values that are significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviation: ROA, return on assets.

We also revisit Giroud and Mueller (2010) using our analyst termination setting. Giroud and Mueller (2010) study the effect of the passage of business combination (BC) laws that weaken corporate governance. They find that firms’ ROA decreases after BC laws, and that the reduction is higher for firms in noncompetitive industries. They conclude that competition mitigates managerial slack and improves operating efficiency.16 We replace the dependent variable equation (1) with ROA and include firm-fixed effects and year-fixed effects. We strictly follow Giroud and Mueller (2010) to use the continuous variable Competition instead of the dummy variable Competition_high. The results presented in Table B.1 and Panel B are consistent with Giroud and Mueller (2010). In Column (1), we find that ROA significantly decreases when governance monitoring weakens. In Column (2), we find that the decrease in ROA is less severe in competitive industries, consistent with the notion that competition mitigates managerial slack.

The results in Table B.1 show that managerial slack and expropriation increase more in noncompetitive industries when analyst coverage reduces, which supports the disciplinary view of competition. Combining these results and our main findings, evidence supports our claim that competition can reduce managerial slack while simultaneously incentivizing financial misreporting. Therefore, simply treating competition as a “good” or “bad” governance mechanism in the agency context fails to capture its multidimensional impact on managerial behavior.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data are either available from data providers or publicly available. The data sources are given in the Appendix A.

REFERENCES

- 1 Anecdotal stories from The Wall Street Journal suggest that earnings manipulation becomes pervasive (Maurer, 2021, 2023).

- 2 Previous literature provides evidence that competition can lead to an inefficient outcome in different settings, such as labor market pressure and short-term performance (Narayanan, 1985), takeover threat and earnings manipulation (Stein, 1988) and capital market pressure and venture capital fundraising (Baker, 2000; Gompers, 1996).

- 3 Following Derrien and Kecskés (2013) and Chen et al. (2015), we treat both types of events as homogeneous to analyst coverage. In an untabulated test, we find that the difference between merger events and closure events on financial reporting quality is not statistically different.

- 4 Our theoretical framework does not differentiate the effect between internal and external corporate governance mechanisms. Empirically, we focus on external corporate governance because our setting leverages analyst termination events.

- 5 Our results are also robust to and more conservative than other clustering methods, such as at brokerage shock level, industry level and industry and year level.

- 6 We follow the literature to use the absolute value of discretionary accruals in our main tests. In additional analyses, we split the sample according to the sign of discretionary accruals and find consistent results.

- 7 The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index has faced some criticisms in the literature. First, it is an industry-level measure of competition that does not reflect firm-level variations. Second, it neglects private firms, which may introduce estimation bias (Ali et al., 2014). Third, it captures only one dimension of competition based on sales, and it is unclear whether a higher HHI indicates less intense competition as it depends on how HHI is formed (i.e., in duopolies). We address these concerns using three alternative measures of competition in Section 5.

- 8 Our sample begins in 1988 because the absolute value of discretionary accruals, our main dependent variable, is not available prior to 1988. Our sample ends in 2018, 5 years after the last analyst termination shock we are able to identify in 2013. This sample is consistent with that used in other studies (e.g., Derrien & Kecskés, 2013; Hong & Kacperczyk, 2010; Kelly & Ljungqvist, 2012). Our results are robust to a 2 or 3-year posttreatment window.

- 9 The economic magnitude in our paper is comparable to that documented in Chen et al. (2015).

- 10 Prior studies that use the same empirical setting rely on the assumption that the brokerage shock is less likely affected by firm-level outcomes. Nevertheless, an alternative story may invalidate this assumption: A higher level of financial misreporting (conditional on being undetected) results in better overall performance for firms in competitive industries, which leads to brokerage firms strategically reducing analyst coverage on these firms. We address this concern by doing the dynamic test in Table 3 Panel C.

- 11 All cross-sectional analyses are based on partitions that are computed prior to the analyst terminations throughout the study.

- 12 We also examine signed discretionary accruals to separately capture upward and downward earnings management. We calculate Positive DA and Negative DA as the absolute value of positive and negative discretionary accruals, respectively, using the modified Jones model controlling for performance. We observe a similar magnitude on the coefficients of the interaction term for both. This suggests that competitive industries are more likely than noncompetitive industries to manage earnings both upward and downward when analysts’ monitoring is weaker. This finding is consistent with prior literature, highlighting various managerial opportunistic motives for directional earnings management.

- 13 The Competition variable is subsumed by the industry-year fixed effects.

- 14 Chen et al. (2015) also examined the impact of analyst coverage on earnings management, proxied by the absolute value of discretionary accruals, and found that managers manager earnings more after analyst terminations. However, they do not test whether this effect is different between competitive versus noncompetitive industries.

- 15 We lose a significant portion of the sample in Panel A of Table B.1 after merging with ExecuComp, which covers only S&P 1500 firms. In Panel B of Table B.1, we require the firms to be incorporated in the United States to determine the application of BC laws; therefore, the sample size is also reduced compared to other tables.

- 16 In one of the additional tests, Giroud and Mueller (2010) also looked at whether the BC laws affect earnings management and whether the impact is different for competitive versus noncompetitive industries. They do not find any significant results for either relationship. The insignificant results may be attributable to a lack of power in their earnings management measure, as they use the directional discretionary accruals rather than the absolute discretionary accruals.