Effectiveness of the mentalisation-based serious game ‘You & I’ for adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities: A randomised controlled trial

Abstract

Background

Mentalising and stress regulation pose challenges for adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (MBID), emphasising the importance of an intervention program. The study examined the effectiveness and social validity of the serious game ‘You & I’ in enhancing mentalising and stress regulation among adults with MBID.

Method

A randomised controlled superiority trial with experimental and waitlist-control groups was conducted with 159 adults with MBID (Mage = 36) at baseline, post-test, and follow-up. Analyses investigated the effects on aspects of mentalising, stress regulation, and social validity.

Results

The experimental group showed decreased stress from negative interpersonal relations, while the control group experienced increased stress (d = 0.26). There were no significant effects on mentalising, but positive user expectations and experiences were reported.

Conclusions

This initial study on ‘You & I’ provides limited evidence of its effectiveness for people with MBID, warranting further examination of the potential of serious games.

1 INTRODUCTION

For people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, the development of positive interpersonal relationships is important for enhancing their quality of life and supporting their mental well-being. Due to factors like social isolation, communication difficulties, and challenges in understanding and expressing emotions, individuals with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities are more susceptible to developing mental health issues, which can consequently hinder their access to positive interpersonal relationships (Baglio et al., 2016; Sigafoos et al., 2017). A key determinant for the development of these relationships is the capacity for mentalising (Allen, 2003), which allows us to understand our own and others' behaviour in terms of mental states. Mentalising is the result of a dynamic interplay between complex social cognitive skills, such as reflective functioning, emotion recognition, perspective taking, and interpreting one's own and others' intentions in social situations (also called theory of mind) (Allen et al., 2008; Arioli et al., 2021). Improving the social cognitive skills and thus mentalising of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities can be beneficial in strengthening their social functioning.

According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, people are classified with a mild to borderline intellectual disability when they have an intelligence quotient between 50 and 85 and development opportunities in adaptive behaviour (social adaptability) (Schalock et al., 2010). Due to developmental delays in the domains of cognition, language, and social cognition, mentalising can be challenging. Indeed, people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities appeared to have difficulties with perspective taking (Benson et al., 1993), emotion recognition (Scotland et al., 2015), and theory of mind (Wagemaker et al., 2022). Moreover, research has shown difficulties in stress regulation for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (Schuengel & Janssen, 2006), which is intertwined with the capacity to mentalise. Mentalising is essential for successfully coping with stress (Allen, 2003), while stressful circumstances also negatively influence the opportunity to learn and apply mentalising skills (Fonagy & Luyten, 2009). Intervention programmes that focus on mentalising together with stress regulation are therefore advised.

Current interventions that promote mentalising are characterised by actively talking and thinking about mental states, thereby promoting curiosity about feelings and thoughts of others and themselves (Feenstra & Bales, 2015). In mentalisation-based treatment (MBT), for example, a therapist asks questions to strengthen the patient's mentalising, such as ‘How do you think and feel about yourself and others?’. Also, according to theory of mind training, participants are asked about the feelings, thoughts, and beliefs of the person. Corrective feedback is provided to prevent participants from accidentally learning incorrect skills (Hofmann et al., 2016). Emotion recognition in people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities is usually taught by repeatedly practicing the recognition of emotions based on facial expressions on pictures or photographs (McKenzie et al., 2000). Cognitive therapy, and specifically the ABC model (i.e., the model that explains how beliefs (B) about events (A) influence emotional/behavioural responses (C); Ellis, 1977) has been used in people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities to improve the recognition of stress signals in the body and to promote strategies to alleviate distress (Jahoda et al., 2017). Thus, diverse kinds of interventions for specific elements within the mentalisation-based approach have been developed during the past two decades.

The efficacy of MBT has been demonstrated in randomised trials, by small to moderate improvements in interpersonal and social functioning of adolescents and families (Byrne et al., 2020). However, no studies on MBT have yet been found in people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. For theory-of-mind training, promising results have been found in children (Hofmann et al., 2016), but mixed results were found for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (Adibsereshki et al., 2014; Ashcroft et al., 1999). Training on emotion recognition has shown to be effective in people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (Wood & Kroese, 2007), and results of CBT to ultimately improve stress regulation in people with intellectual disability are promising (Bruce et al., 2010). Therefore, more research on the effect of mentalisation-based interventions for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities can provide valuable insights to the existing literature.

Current treatments for improving (important abilities for) mentalising are time-consuming, require supervision from professionals, and are very expensive (Bales et al., 2012; Laurenssen et al., 2016). These interventions may not take sufficient account of the needs of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (Montoya-Rodríguez & Molina-Cobos, 2019). In learning new abstract skills, special attention needs to be focussed on working memory, short-term memory capacity, cognitive development, and the attention span of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (De Wit et al., 2012; Van Nieuwenhuijzen et al., 2011). Also, people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities benefit from a safe and predictable environment to practise abilities without risks or consequences (Torrente et al., 2012). Innovative intervention methods, such as serious games, take these needs into account. Serious games are computer applications designed to combine self-paced learning and serious aspects with playful elements (Terras et al., 2018; Torrente et al., 2012). They offer a safe, predictable, and reassuring test environment to solve dilemmas and practise abilities. Serious games also provide an opportunity to include key elements of social-cognitive skills training, such as a voice-over to provide instructions and ask questions, and the identification with a character. Serious games can be used at low cost and provide the opportunity to practice new skills in a setting that is (un)likely to occur in everyday life. Also, by using repetition and offering ‘ready-made’ explicit representations of complex concepts (Terras et al., 2018; Torrente et al., 2012), serious games can particularly support the learning of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities.

With the intention to improve mentalising and stress regulation of adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, the serious game ‘You & I’ was developed (Derks et al., 2022) in co-operation with people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. In the present study, we examined the effectiveness of the serious game ‘You & I’ through a parallel superiority randomised controlled trial (RCT), asking the following questions: (a) Does the serious game ‘You & I’ significantly improve mentalising of adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities? And (b) does the serious game ‘You & I' significantly improve stress regulation in adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities? Based on the underlying learning principles of the game, four concepts were included to measure mentalising: (1) reflective functioning, (2) perspective taking, (3) emotion recognition, and (4) theory of mind. We hypothesised that playing the serious game ‘You & I’ would be associated with an improvement in all four abilities, as well as an improvement in stress regulation. We also examined how the serious game ‘You & I’ was evaluated in terms of social validity. We predicted that before (expectations) and after (experiences) the intervention, the participants rate the game as useful, pleasant, and suitable for improving mentalising and stress regulation through playing the serious game.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

We conducted a parallel superiority RCT (Spieth et al., 2016) with two parallel conditions (an intervention condition, and a control condition), with three repeated measures. The experimental group played the serious game ‘You & I’, whereas the control group was placed on a waitlist. Effects were measured at baseline (T0), post-test (T1, 5 weeks after baseline), and follow-up (T2, 6–8 weeks after post-test). The study was registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR7418) and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Amsterdam, the Netherlands (METc VUmc 2018.007, NL60353.029.17). For the details of the study protocol, see Derks et al. (2019).

2.2 Participants

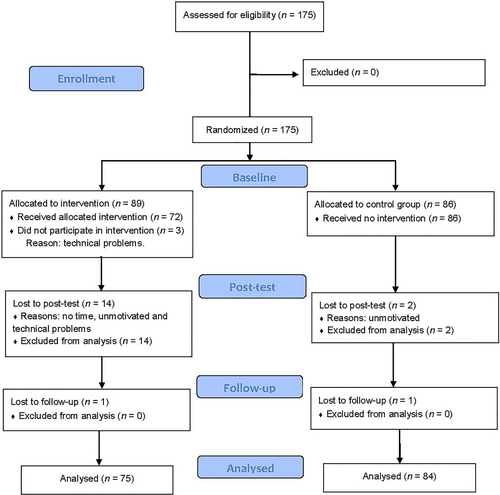

A total of 175 adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (aged ≥18 years) were recruited to participate in the study. Deaf and/or blind participants as well as participants with serious mobility impairments for whom computer operation is not possible were excluded. After baseline, 16 participants dropped out and could not be included in the analyses, so retaining 159 participants. Figure 1 shows the enrolment and drop-out of participants in the study based on the Consort 2010 Statement (Schulz et al., 2010). Post hoc power analysis showed that this sample size yielded sufficient statistical power (β = .80) to detect a within (baseline, post-test, and follow-up) and between (experimental and control group) effect size of d ≥ 0.101 (G*power 3.1.9.4; Faul et al., 2007).

The student t-test was used to assess attrition bias in the experimental group. No significant baseline differences were found between participants and drop-outs regarding demographic variables, autistic traits, or wellbeing. Moreover, Levene's tests were non-significant, indicating equal variances in the experimental and control groups.

2.3 Procedure and randomisation

Data collection occurred between October 2018 and July 2019. Participants were recruited from the populations of four Dutch care organisations (ASVZ, Cordaan, Bartiméus, Ons Tweede Thuis) specialised in providing care or support for people with disabilities, through social media (e.g., announcements on websites, Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook), letters and informational brochures and presentations for possible participants and caregivers. Participants could register using a form at their care organisation or on the website, or by emailing the researcher. Registered participants received a participant number, for pseudonymization of the questionnaires. An independent researcher used a computerised random number generator to perform individual randomisation into two parallel groups through block randomisation within the four care organisations and a category ‘other’ with block sizes varying between four and six.

Before baseline assessment, an informed consent form was signed by the participant. In case the signing of official forms could not be done (only) by the participant, their legal representative signed an informed consent with the agreement of the participant. Independent researchers with a signed confidentiality agreement (students and research assistants) assisted participants in completing the questionnaires during all assessments, following a standard protocol with detailed instructions. Each digital questionnaire programmed in Qualtrics software took approximately 90 min to complete and was filled out at the home or care home of the participant. After completing baseline assessment, participants were informed by the independent researcher the group to which they were assigned. Both participants and researchers were blinded until after baseline, whereafter blinding became impossible for participants and researchers. Participants assigned to the control group were placed on a waitlist but could receive care-as-usual. Apart from inquiries related to their care and work and/or day care, neither the control group nor the experimental group was closely monitored between baseline and post-test assessments.

Participants assigned to the experimental group had the opportunity to play the serious game ‘You & I’, in a comfortable setting, such as a place where they could concentrate best. The serious game had eight levels, each taking between 30 to 45 min to complete. Participants were instructed to play two levels per week, to spread playtime over the week, and to complete one level at a time. The independent researchers, not present when participants played the game, contacted participants either in person, via e-mail or by phone with reminders to play the game (the frequency varied depending on the individual progress) and to confirm post-test assessment (verify the appointment at least the day before and check whether the entire game was played). Most participants were able to finish the game in 3–3, 5 weeks on average (SD = 2.23; retrieved from available but not complete game statistics), some with extra support and encouragement. When participants had not finished the game within 4 weeks, it was discussed whether the game could be finished within a certain period of time, with a new appointment for post-test. Follow-up assessments were completed 6–8 weeks after post-test. Control group participants were then also able to play the serious game.

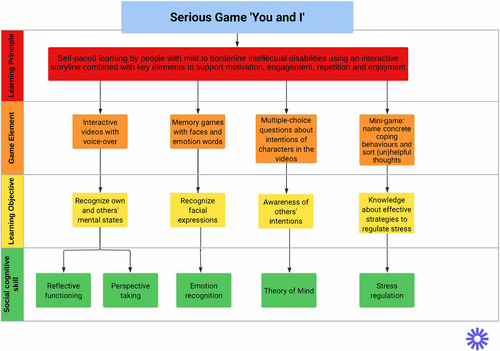

2.4 Intervention

The serious game ‘You & I’ was developed by a researcher who coordinated the co-creation process and did not participate in this RCT study. The last author was the supervisor during the development of the game and the first and second author were not involved in the development of the game (Derks et al., 2022). The game aims to improve mentalising and stress regulation in adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. The game is based on the principles of active talking and thinking of mental states (Bateman & Fonagy, 2013), and the specific learning needs of people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (Torrente et al., 2012). The game comprises of four game elements, included to contribute to the training of mentalising skills (Figure 2). First, based on the key elements of MBT, a voice-over indirectly instructs participants to recognise and name their mental state and that of others, expected to contribute to reflective functioning and perspective taking. Second, a memory game uses matching of facial expressions with emotions, to promote emotion recognition. Third, videos on interactions between characters are followed-up by questions about intentions of others, and the participants' feelings, expected to promote theory of mind. Fourth, concrete behaviours (e.g., counting to 10, phoning somebody, taking a deep breath) and thoughts (e.g., ‘It is OK if things do not go according to plan’, ‘It is OK to make mistakes’) are explained and practiced to help clients when experiencing stress.

The serious game is story based and revolves around a main character called Mo, whom the player follows on a trip, while experiencing his thoughts, feelings, wishes and needs. Players were stimulated to relate these to themself and others and to learn which strategies contribute to better mentalising and stress regulation. Each level has its own theme (e.g., one's own thoughts or thoughts of others) and content (related to the theme of the level) but consists of the same structure and elements as other levels. These elements are videos following Mo's journey, multiple-choice questions, an emotion picture game, a stress measurer, and a game about stress. This information was provided to the participants before the start of the game. For more comprehensive details on the co-creation process of the serious game ‘You & I’, see the associated article (Derks et al., 2022).

2.5 Primary outcome measures

At baseline, post-test, and follow-up, mentalising was examined using four measures described below.

2.5.1 Mentalising

Reflective functioning was assessed with the Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (RFQ) adapted for use among people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (Derks et al., 2023). The RFQ is a brief self-report screening originally developed by Fonagy et al. (2016) to measure inabilities of mentalising along two subscales: more extreme levels of certainty (hypermentalising) and uncertainty (hypomentalising) about mental states. However, in recent papers, it was concluded that the two-factor structure in the original 8-item RFQ, in which four items loaded on both factors, is problematic because of the dependence between these items (Müller et al., 2021; Woźniak-Prus et al., 2022). Therefore, a one factor solution was proposed, measuring mentalising as a unidimensional construct with seven items (omitting original item seven (‘I always know what I feel’) given its low factor loading). Derks et al. (2023) validated this version for people with intellectual disabilities and added three items with a specific focus on cognitions and emotions of the other. The adapted RFQ has 10 items, such as ‘I don't always know why I do something’ and ‘It is easy for me to know what other people are thinking and feeling’. A 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) was used. Factor analysis agreed that two subscales could be created: one with items focused on the self and one's own feelings and thoughts (subscale Self with items 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) and one with items focused on the self in relation to the feelings and thoughts of others (subscale Other with items 1, 8, 9, and 10). For the Self subscale, Cronbach's alphas were .74, .67, and .75 for baseline, post-test, and follow-up, respectively. For the Other subscale, Cronbach's alphas were .60, .43, and .62, respectively, indicating poor to good internal consistency of the two subscales.

Perspective taking was assessed using the Perspective Taking (PT) subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1980). The PT measures the ability to adopt the psychological point of view of others using seven self-reported items scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from does not describe me well (1) to describes me very well (5). Items were either positively formulated (e.g., ‘I believe that there are two sides to every question and try to look at them both’) or negatively formulated (e.g., ‘If I'm sure I'm right about something, I don't waste much time listening to other people's arguments’). This measure was also adapted for adults with intellectual disabilities by removing unnecessary wording, simplifying concepts, and asking for feedback from adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. The complete IRI with custom response categories (none, sometimes, and all times) was previously adequately reliably (Cronbach's α = .71) used in a sample of adults with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities (Michie & Lindsay, 2012).Negative items were positively recoded and after excluding these two items with double denial that appeared problematic, Cronbach's alpha increased to .64 at baseline, .57 at post-test, and .70 at follow-up, indicating more acceptable internal consistency. The mean score on the PT is based on five remaining items, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of perspective taking.

Emotion recognition was assessed using the Radboud Faces Database (RaFD; Langner et al., 2010). Participants viewed 50 colour photographs of unfamiliar faces of different Caucasian and Moroccan adults, each displaying either anger, fear, happiness, sadness, and neutral, which participants had to name. The photographs included averted gaze (left and right), as well as direct frontal gaze orientations, of which eight could be classified as ‘difficult’ for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities (Van Rest, 2020). Based on the number of incorrect (0) and correct (1) answers, the mean score was calculated for each participant. With an agreement rate of 82% between chosen and intended expressions at baseline (median 86%, SD = 12.8%, N = 149), the RaFD had good psychometric qualities in the current sample of adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities.

Finally, theory of mind was assessed with the non-verbal Frith-Happé Animations Test. The test, which has previously been used in children with intellectual disabilities (Abell et al., 2000). It consists of a series of computer-presented animations featuring one large red and one small blue triangle moving around the screen in three types of animations (i.e., theory of mind, goal-directed action, and random animations) each lasting between 34 and 45 s. Two practice animations were shown to the participants to ensure that they understood the task. After watching each clip, the participants were asked, ‘What happened in the animation?’ Verbal descriptions were recorded and scored by two independent coders, who were trained in using the scoring criteria for the complexity of mental state terms used (i.e., intentionality; 0–3) and the accuracy of the answer given (i.e., appropriateness; 0–2). Higher scores indicated the answers better matched the animations. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs; mean-rating (k = 3), consistency-agreement, 2-way mixed-effects model, 95% confidence interval) were calculated between the scores of the coders with the aim of achieving an inter-coder reliability of 70%. First calculations revealed an ICC < .70. Participants on which the coders differed by more than one point (n = 24) were discussed and a joint score reached. The final inter-rater reliability at baseline (ICC appropriateness score = .76; ICC intentionality score = .80), post-test (ICC appropriateness score = .70; ICC intentionality score = .83), and follow-up (ICC appropriateness score = .71; ICC intentionality score = .83) was acceptable to good.

2.6 Secondary outcome measures

Stress regulation was assessed at baseline, post-test, and follow-up using two measures described below.

2.6.1 Stress regulation

The Lifestress Inventory (LI) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 30 items to measure the experience and impact of the stress in people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities using themes that represent their experiences (Fogarty et al., 1997). This measure was translated into Dutch and checked by adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. Participants were asked to indicate the impact of the stressor ranging from 1 (no stress) to 4 (a great deal of stress), whether they had experienced a potential stressor in a certain situation (e.g., Do people treat you as though you are different? Do people interrupt you when you are busy?). This score, called the Impact Score, was calculated with the answers ‘not experienced’ and ‘experienced but it caused no stress’ taken together. Higher scores indicated an increased stress experienced from a stressor. Equivalent to the subscales in Fogarty et al. (1997), three scores could be calculated: General Worry, Negative Interpersonal Relations, and Competency Concerns. Adequate reliability was found, with Cronbach's alphas of .66 at baseline, .68 post-test, and .71 at follow-up for General Worry; .74 at baseline, .75 post-test, and .76 at follow-up for Negative Interpersonal Relations; and .67 at baseline, .70 post-test, and .74 at follow-up for Competency Concerns.

A short, non-invasive nine-item stress self-efficacy questionnaire was developed using Bandura's guide for constructing self-efficacy scales (Bandura, 2006), specifically focussing on the skills learned in the serious game ‘You & I'. Participants were asked, on a scale from 0 (not at all sure) to 10 (very sure), how certain they were about how they can know, feel, and cope with stress. Higher scores indicated better self-efficacy. With a Cronbach's alpha of .77 at baseline, .83 post-test, and .86 at follow-up, the items on the perceived self-efficacy scale were reliable for measuring self-efficacy regarding stress regulation.

2.7 Demographic variables – minimal dataset (MDS)

Demographic variables were measured at baseline using the minimal dataset (MDS) ‘Basic MDS’ and ‘Basic MDS for adults with an intellectual disability’ (Kunseler et al., 2019), including the Personal Wellbeing Index – Intellectual Disability (PWI-ID; Cummins & Lau, 2005). The MDS is a set of questions on demographic variables for everyone who collects data on people with intellectual disabilities. The PWI-ID measured the satisfaction of participants in eight life domains by rating their happiness on each domain on a scale of 1 (not happy at all) to 10 (very happy). Participants reported their care organisation, age, gender, education, received care, work and/or day care, and personal wellbeing.

2.8 Social validity scale (SVS)

To assess the usefulness, pleasantness and suitability of the intervention procedure, the Social Validity Scale (SVS) was added based on Seys (1987). The SVS questionnaire used a 5-point Likert scale with different formulations of response categories but corresponding from completely disagree (1) to neutral (3) to completely agree (5). The individual items indicating usefulness, pleasantness, suitability to develop mentalising and stress regulation stress were determined both at baseline (expectations) and post-test (experiences). Participants in the experimental and control groups answered seven questions about expectations at baseline. Post-test, the participants in the experimental group completed 10 questions about experiences. Examples of questions were ‘Playing the serious game “You & I” seems to me… (pleasant)’ and ‘Playing the serious game “You & I” was… (pleasant)’.

2.9 Autism spectrum quotient (AQ-10)

Autistic traits were examined at baseline using the autism spectrum quotient to study potential confounding effects of autistic traits (AQ-10; Allison et al., 2012). The self-report questionnaire consists of 10 items measured on a 4-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from definitely agree (1) to definitely disagree (4). As the AQ-10 has not yet been used for adults with intellectual disabilities, it was adapted for adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities by simplifying the concepts and was checked by co-researchers with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities to align with our target group. A mean score was calculated, with higher scores indicating more autistic traits. Allison et al. (2012) reported good psychometric properties of the AQ-10 in an adult sample, with a Cronbach's alpha of .85. A Cronbach's alpha of .42 was found in the current study.

2.10 Data analysis

Intention-to-treat analysis including participants with data for at least T1 or T2 (all participants completed baseline) were performed. The variables were critically studied for outliers and skewness. No problematic outliers were detected. The appropriateness score of the Frith-Happé animations test, and the impact score of the LI subscales were positively skewed, ranging from 0.58 to 1.15, indicating low scores for most participants. The subscales of the RFQ, the PT, RaFD, the intentionality score of the Frith-Happé animations test, and the self-efficacy scale were negatively skewed, ranging from −0.175 to −1.03, indicating high scores for most participants. Missing values analyses using Little's MCAR test showed that missing values were completely random (χ2 (43, N = 158) = 53.12, p = .139).

Potential confounding effects of demographic variables (age, gender, education, received care, work and/or day care), diagnoses of autism, autistic traits, care organisation, and personal wellbeing were assessed to determine which covariates may require inclusion in the linear mixed models. Covariates that significantly improved the model fit (based on −2Log likelihood criterion) and individually significantly related to the outcome measures were included as potential random effects (see Supplemental information, Table S1 for the covariates included in each model).

To assess the effect of the serious game on primary and secondary outcomes (i.e., mentalising and stress regulation), linear mixed effects modelling was used. A model was fitted in SPSS (version 27) separately for each outcome variable. Data were restructured, combining post-test and follow-up measures into one variable for each outcome and modelled as linear change model (Twisk, 2006). A time variable was computed to indicate the assessment point. To control for baseline differences, the baseline measurement was entered as a predictor and time as a fixed effect and as a random effect, controlling for slope variation between participants. Next, additional random effects of covariates were added to the model. Lastly, group and the group x time interaction were added as fixed effects. The best fitted models were selected based on significant improvement through the −2 Log likelihood criterion. When time, group, and the time × group interaction were entered, covariance type was set to the identity of the variance–covariance structure of the data (Twisk, 2006).

Finally, social validity of the serious game was described by the ratings at baseline and post-test. A one-sample t-test with the value 3 as the reference score (neutral) was used to determine whether the scores on the social validity scales were significantly greater than 3 (neutral).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Preliminary analysis

The demographic variables of the sample are provided in Table 1. No significant differences were found between the experimental and control group at baseline.

| Group | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | |||

| n = 75 | n = 84 | |||

| Care organisationa | 1 | 6 | 9 | 15 |

| 2 | 7 | 5 | 12 | |

| 3 | 23 | 30 | 53 | |

| 4 | 9 | 9 | 18 | |

| 5 | 30 | 31 | 61 | |

| Gender | Male | 43 | 45 | 88 |

| Female | 32 | 39 | 71 | |

| Age, years | M (SD) | 37 (12.70) | 36 (12.39) | 36 (12.51) |

| Country of birth | Netherlands | 69 | 80 | 149 |

| Suriname | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Indonesia | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Germany | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Education | None to regular primary educationb | 30 | 27 | 57 |

| Secondary (special) education | 37 | 46 | 83 | |

| Vocational secondary education | 7 | 7 | 14 | |

| Receiving care | 24/7 | 31 | 42 | 73 |

| Less than 24/7 | 33 | 30 | 63 | |

| Work and/or daytime activity | Work (paid to voluntary) | 31 | 39 | 70 |

| No work (school to home stay) | 43 | 44 | 87 | |

| Extra care | Mentor | 54 | 61 | 115 |

| Administrator | 58 | 69 | 127 | |

| Curator | 14 | 17 | 31 | |

| Autistic traits | M (SD) | 2.5 (0.42) | 2.5 (0.48) | 2.5 (0.45) |

| Personal wellbeing | M (SD) | 7.9 (1.26) | 8.0 (1.23) | 8.0 (1.24) |

- a 1–3 = specific care facilities for persons with intellectual disabilities, 4 = care facility for persons with visual and intellectual disabilities, 5 = additional care facilities for persons with intellectual disabilities.

- b This includes primary special education.

3.2 Effects of the intervention

The mean total scores for the abilities important for mentalising and stress regulation at all three assessments are given in Table 2. Except for a slight significant difference for the LI subscale General Worry, no significant differences were found in outcome measures at baseline between participants in the experimental and waitlist-control groups.

| Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | |||||

| (n = 75) | (n = 84) | |||||

| Baseline | Post-test | Follow-up | Baseline | Post-test | Follow-up | |

| Mentalisation | ||||||

| Reflective functioning | ||||||

| Self | 4.36 (1.38) | 4.60 (1.10) | 4.29 (1.33) | 4.17 (1.31) | 4.39 (1.28) | 4.24 (1.26) |

| Other | 3.96 (1.30) | 4.05 (0.95) | 4.15 (1.24) | 3.98 (1.26) | 4.17 (1.22) | 3.91 (1.28) |

| Perspective taking | 3.67 (0.84) | 3.70 (0.75) | 3.69 (0.88) | 3.67 (0.83) | 3.78 (0.77) | 3.79 (0.84) |

| Emotion recognition | 0.82 (0.13) | 0.85 (0.11) | 0.83 (0.13) | 0.81 (0.13) | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.82 (0.14) |

| Difficult pictures | 0.60 (0.18) | 0.67 (0.17) | 0.67 (0.18) | 0.62 (0.18) | 0.65 (0.21) | 0.65 (0.20) |

| Theory of mind | ||||||

| Appropriateness | 0.51 (0.26) | 0.56 (0.29) | 0.55 (0.29) | 0.55 (0.25) | 0.52 (0.24) | 0.50 (0.24) |

| Intentionality | 1.15 (0.41) | 1.14 (0.42) | 1.12 (0.42) | 1.19 (0.38) | 1.18 (0.38) | 1.16 (0.42) |

| Stress regulation | ||||||

| Stress experience and impact | ||||||

| General Worry | 1.17 (0.24) | 1.17 (0.23) | 1.18 (0.28) | 1.27 (0.35) | 1.28 (0.36) | 1.27 (0.35) |

| Negative interpersonal relations | 2.08 (0.64) | 1.96 (0.65) | 1.82 (0.56) | 2.07 (0.67) | 1.93 (0.58) | 1.96 (0.64) |

| Competency Concerns | 1.59 (0.47) | 1.56 (0.49) | 1.57 (0.52) | 1.68 (0.55) | 1.64 (0.56) | 1.63 (0.57) |

| Stress self-efficacy | 6.24 (1.53) | 6.43 (1.75) | 6.55 (1.76) | 6.17 (1.86) | 6.25 (2.02) | 6.52 (1.91) |

- Note: Data are given as mean (standard deviation).

No significant differences were found for mentalising or stress regulation measures, regardless of study condition.

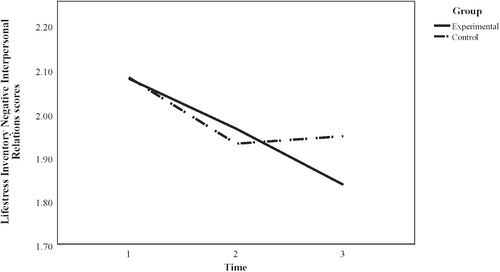

A significant interaction effect of time by group was found for the LI subscale Negative Interpersonal Relations, with a small to medium effect size (B = 0.16, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.02–0.31], p = .022, d = 0.26). Although the perceived impact of stressors decreased in both groups from baseline to post-test, the scores increased again in the control group but decreased further in the experimental group (Figure 3). No other significant group x time effects were found.

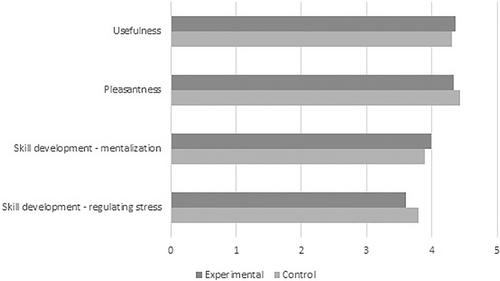

3.3 Social validity results

Figure 4 shows the baseline expectations on the social validity subscales. Pre-intervention scores indicated that the participants expected the intervention to be useful, pleasant, and suitable for improving mentalising and stress regulation through playing the serious game. No significant baseline differences were found between the two groups (all p ≥ .153). Furthermore, a one-sample t-test showed that, for the experimental group, the mean post-test scores for all subscales differed significantly from the neutral value (i.e., higher than 3.0; see Table 3). The results suggested that also after the intervention, the participants rated the game as valuable and pleasant. Moreover, participants reported that they progressed in developing mentalising and stress regulation through the serious game, indicating the intervention was experienced as suitable for improving these abilities.

| Experimental group | t | df | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min – Max | M | SD | ||||

| Usefulness | 2–5 | 4.14 | 0.64 | 15.041 | 70 | .000 |

| Pleasantness | 1–5 | 4.11 | 0.84 | 11.195 | 70 | .000 |

| Skill development – mentalisation | 3–5 | 3.67 | 0.57 | 9.840 | 70 | .000 |

| Skill development – regulating stress | 2–5 | 3.46 | 0.61 | 6.468 | 70 | .000 |

- Note: t-test results represent the one sample t-test with the value 3 as a reference score (neutral) to determine significant positive post-test evaluations. Original scale ranges from 1 to 5.

4 DISCUSSION

The present study examined whether the serious game ‘You & I’ could improve mentalising and stress regulation in adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. In conclusion, only limited evidence is found for the effectiveness of the serious game ‘You & I’. No significant benefits of the game were found on mentalising. However, the intervention significantly improved one indicator of stress regulation. Specifically, participants who played the serious game ‘You & I’ during the study period showed a continuous decrease in the perceived impact of stressors regarding negative interpersonal relations compared to participants who were in the waitlist-control group.

The results showed that stress regulation but not mentalising was improved in participants playing the serious game ‘You & I’. The game specifically pays attention to actions that regulate stress, such as concrete behaviours (e.g., counting to 10, phoning somebody, taking a deep breath) and thoughts (e.g., ‘It is OK if things do not go according to plan’, ‘It is OK to make mistakes’) to help unwind when experiencing stress. These skills may be used in concrete situations in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities, including negative interpersonal interactions, such as arguments and bullying (Fogarty et al., 1997). Stress regulation skills may prevent immediate negative responses and help provide a better overview of the situation, which in turn may reduce friction and stress.

The serious game was not able to improve the various aspects of mentalising, in this study operationalised as reflective functioning, emotion recognition, perspective taking, and theory of mind. First, the lack of support for the effectiveness of these aspects might result from the inability of the game (elements) in its current form to improve mentalising. A second explanation could be that the translation and generalisation to the events of daily life may still be too far away from in game exercises of situations experienced by the main character (Mo). Another explanation lies in the additional time required for improvements in mentalising resulting from the intervention. That is, first, due to the complexity of mentalising, is it difficult and time-consuming to notice any significant changes in this cognitive process. Second, the internalising and integrating of the acquired knowledge may take longer in individuals with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities, for example, because of the hindered information processing (Van Nieuwenhuijzen et al., 2011). Third, considering the interaction between mentalising and stress regulation, the development of stress regulation may in turn offer opportunities to improve mentalising later in time.

The social validity scale showed that before (expectations) and after (experiences) the intervention, the participants rate playing the game as useful, pleasant, and suitable for improving mentalising and stress regulation. The co-creation process of the serious game ‘You & I’ (Derks et al., 2022) aimed to develop an effective intervention aligned to the needs and wishes of the end-users. This may have contributed to the indications of the game as ‘fun to play’ and ‘an apt way to learn and develop mentalising and stress regulation’. Therefore, the serious game seems to match the interests and abilities of the participants, which can be essential support for implementing the game in health care for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities.

4.1 Limitations and implications for future research

Although RCTs are suitable for investigating the effectiveness of interventions because of reduced susceptibility to bias, this does not mean the process is bias-free. In this study, bias due to partial blinding, responses, and differential drop-out need to be mentioned.

First, blinding was partially possible due to awareness of the assignment to the experimental or waitlist-control group and the continuity of independent researchers supporting the same participants in completing the questionnaires throughout the study. This could have caused control group participants to seek out other interventions to compensate and biased assessments by the independent researchers (Higgins et al., 2021). However, attempts have been made to minimise this form of bias by offering control group participants the intervention later, using a protocol for the independent researchers to assess outcomes and using at least participant-reported outcomes, free of the judgements of the researchers.

In addition, the wait-list control group was considered the most appropriate for the current RCT study due to the practical burden that no other comparable intervention was available. However, including a wait-list control group as control condition increases the chance of finding the largest effect (Mohr et al., 2009). Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that the effects found in the RCT might have been influenced, at least partially, by other factors. Specifically, factors like feeling essential, valued, and heard (i.e., core condition for therapeutic change; Rogers, 1957) or positive expectations on improvement due to participation in the intervention condition. While efforts were made to minimise potential side effects associated with the intervention condition, such as participants playing the game individually, it would be beneficial for future studies to examine these effects more comprehensively. One approach could involve comparing the serious game intervention group with another group undergoing a (non-)game-based intervention.

Second, response biases can occur due to the interference between the use of self-report questionnaires about mentalising and stress regulation, in particular about mentalising and the reflective abilities of the participants. As mentalising is the abstract ability sought to be improved in the game, reflection can be challenging, especially in the RFQ and PT, leading to participants' answers being inconsistent with reality (Finlay & Lyons, 2001). Related to this are the mediocre Cronbach's alphas found for RFQ Other subscale and the perspective taking subscale, indicating poorer internal inconsistency (Ponterotto & Ruckdeschel, 2007). Furthermore, as the results from the RaFD indicate, the participants had relatively high scores on emotion recognition skills at baseline than initially expected, providing little room for improvement (ceiling effect). The skewness of the RaFD scores may have also reduced the effect sizes due to greater measurement error (Kheradmandi & Rasekh, 2015). Although the RFQ, PT, and RaFD were validated for this population (Derks et al., 2023; Langner et al., 2010; Michie & Lindsay, 2012), these limitations may have increased the probability of finding non-significant effects (type II errors; Ponterotto & Ruckdeschel, 2007). Sharing an important lesson learned, it might be advisable to conduct a pilot or feasibility study before performing an RCT study. This can test whether the proposed outcome measures are suitable and sensitive for possible change during the intervention (Eldridge et al., 2016).

This also applies to the AQ-10, indicating that items are not perfect error-free indicators of the underlying construct of autistic traits. Kent et al. (2018) published their study on the reliability of the AQ-10 and a revised AQ-10 for people with intellectual disabilities. Future research is therefore advised to use the revised AQ-10, including additional analyses to examine the effects of autism with regards to the serious game ‘You & I’. Future research could moreover use multi methods to take into account the disadvantage of self-report questionnaires, such as in the form of proxy reporting through caregivers who answer as if they were in the shoes of their client (Emerson et al., 2013).

Though the study had a sufficient sample size given its power calculation, the size of the experimental group was smaller than the control group due to differential drop-out in the experimental group. Consequently, participants that were included in the analyses may systematically differ from the ones that were excluded from the analyses. This is called attrition bias (Higgins et al., 2021). A check of assumptions revealed no significant differences between participants and drop-outs in the demographic variables at baseline and no difference in the test for equality of variances. Therefore, no complications or distortion of the results are expected due to differential drop-out.

Finally, using a serious game to significantly improve mentalising and stress regulation in people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities requires further investigation. Expected improvements were not (consistently) found, raising at least two questions. First, is a serious game (in its current form) an appropriate intervention to improve mentalising? Second, were participants able to internalise the difficult-to-learn mentalising concept? If so, do certain individuals (such as those facing specific challenges in mentalising) obtain increased gains from playing the game? Future research could gain further insights and refine the serious game ‘You & I’ to enhance its effectiveness and impact. That is, for example, by focusing on the effects of the game for and the underlying learning process of different people, the effects of different game elements, or the effects of including extra elements such as homework. As could have been performed prior to the start of the RCT, to carry out the refinements in advance, a pilot or feasibility RCT study can be conducted (Thornicroft et al., 2011). Moreover, a recent study recommended the involvement of professionals in the learning process of people with intellectual disabilities to enhance the effect of a serious game and facilitate the transfer of what has been learned in the serious game into practical settings such as real-life situations with others (Tsikinas & Xinogalos, 2019). This potential positive effect of playing the game together with the caregiver should be examined.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Although the RCT revealed a reduction in stress after the intervention and users scored the serious game as useful, pleasant, and suitable on the social validity scale, no significant results on mentalising were found. The serious game ‘You & I’ is the first game focussed on mentalising and stress regulation for adults with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities. This brief intervention, specifically developed for the user group (Derks et al., 2022), has several features that enhance usability, such as a small-time investment (30 to 45 min twice per week for 4 weeks) and a low playing threshold as a web-based program with a personal log-in, which only requires a workable internet connection and a personal computer or tablet (smaller mobile devices are not recommended due to limited visibility). With these features but only limited effects of the game in its current form, the potential of a serious game for people with mild to borderline intellectual disabilities should be further examined.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all participants in our study. We thank Suze van Wijngaarden for initiating the study of the effectiveness of the serious game ‘You & I’ and her contribution to the development of the game. Also our research assistant, student assistants, and students for their commitment during the data collection. We are grateful for the help within the care organisations in encouraging and recruiting participants for our study. Special thanks to our contact persons at ASVZ, Bartiméus, Cordaan, and Ons Tweede Thuis. Last but not least, we thank the co-researchers for their active participation in the study, especially during the development of the game and the recruitment of participants.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development ZonMw, Postbus 93 245, 2509 AE Den Haag The Netherlands. Project number 845004004.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.