Granulomatous Dermatitis in a Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus holbrooki)

Case Presentation

An 8-month-old spadefoot toad (Scaphiopus holbrooki) was presented to the North Carolina State University (NCSU) for evaluation of a proliferative to ulcerative dermatitis of 1-month duration. On physical examination, the toad appeared to be in good body condition. Examination of the skin revealed multiple distinct to coalescing white, raised foci of various sizes, from 1 mm to 5 mm in diameter. Several of the lesions were ulcerated. Though the skin was diffusely affected, the lesions appeared to be concentrated on the lateral surface of the animal and in the inguinal and axillary regions. A biopsy of the skin lesions was obtained, and touch imprints were submitted for cytologic examination (Figure 1).

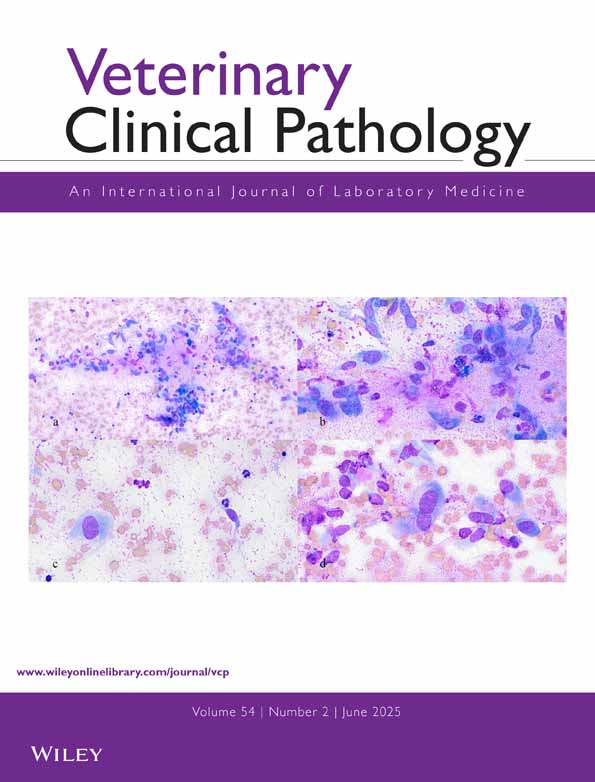

Touch imprint of a white, raised skin lesion on a spadefoot toad (A, B). Wright-Giemsa, ×60.

Cytologic Interpretation

Cytologic examination of 2 slides that were moderately cellular and mildly hemodiluted revealed a mixed cell population consisting primarily of equal numbers of nondegenerate neutrophils and macrophages. A moderate number of eosinophils and lower numbers of small lymphocytes were noted. Multinucleated giant cells were observed frequently. Several dark blue-green pigmented septate fungal hyphae, approximately 4 μm in width, were scattered throughout the specimen (Figure 1). A moderate number of sclerotic bodies also were observed, both alone and in small clusters. These structures were spherical, approximately 10–15 μm in diameter, and had a thick dark wall with a blue-green color. The pyogranulomatous inflammation was compatible with a fungal infection. The primary differential for the fungal hyphae and sclerotic bodies was chromomycosis.

Histologic Interpretation

Histologic examination of the skin biopsy revealed findings similar to those observed in cytologic specimens. The hematoxylin and eosin-stained skin sections were characterized by multilobular to coalescing dermal masses composed primarily of macrophages and multi-nucleated giant cells. A moderate number of eosinophils was scattered throughout the granuloma. Lower numbers of neutrophils and lymphocytes were also observed. Scattered within the granulomas were moderate numbers of spherical, thick-walled septate sclerotic bodies (Figure 2). The sclerotic bodies were seen individually, in small clusters, and occasionally within multinucleated giant cells. Brown-pigmented septate hyphae were also observed infrequently throughout the specimen. Both tissue forms of the fungus were present within the epidermis, along with mild mononuclear inflammation. The histologic diagnosis was granulomatous dermatitis with an intralesional fungus, consistent with chromomycosis.

Histologic section of a skin mass from a spadefoot toad. Note the sclerotic bodies and fungal hyphae. Hematoxylin and eosin, ×60.

Skin samples were submitted for fungal cultures at multiple temperatures; however, isolation of the fungus was not possible because of bacterial overgrowth. The diagnosis of chromomycosis was based on cytologic and histologic findings.

Discussion

Chromomycosis, more commonly referred to as chromoblastomycosis in the human medical literature, is a chronic disease of skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by a group of pigmented saprophytic fungi.1,2 Etiologic agents include certain species of fungi of the genera Phialophora, Cladosporium, Fonsecaea, and Rhinocladiella. Although present worldwide, the disease tends to occur more frequently in tropical and subtropical regions.3 Chromomycosis is an infrequent disease of human beings, and rare cases have been reported in a cat, horse, and snake.4–6 The disease has zoonotic potential, and precautions must be taken, particularly by those who are immunocompromised.3,4

The organism is transmitted primarily through contact with a contaminated environment. The fungus is usually traumatically implanted into the skin and subcutaneous tissues.3,4 Skin lesions may include raised, white papular to vesicular lesions that may ulcerate.4 Lower limbs are typically affected, and the disease tends to be localized to the skin and subcutaneous tissues in mammals.4,5 A systemic form of chromomycosis can be seen in amphibians such as the toad and frog, resulting in granulomatous disease of internal organs.7–9 Toads appear to be more susceptible to the disease when they are debilitated and stressed.3,10 This affected toad died 1 week after presentation at NCSU. Systemic disease could not be confirmed because a necropsy was not performed.

The diagnosis of chromomycosis by cytologic or histologic examination requires identification of sclerotic bodies (the hallmark of chromomycosis) in the specimen.2 Sclerotic bodies are the nonbudding fungal form.2 This tissue form reproduces by septation and appears either singly or in clusters as round to oval cells, approximately 4–12 μm in diameter with thick walls that appear dark brown in histologic specimens.2 Brown-pigmented hyphal forms also may be observed. Because of the pigmentation, special stains are not required for detection.2 Fungal culture can be performed to identify the exact species involved. The inflammatory response associated with chromomycosis is typically granulomatous. Variable numbers of multinucleated giant cells may be observed, and the organism may be found within these cells.1–3

Another consideration for the presence of pigmented hyphae and spherical structures is phaeohyphomycosis. The agents of phaeohyphomycosis are commonly observed in tissues as yellow-brown septate, sometimes branched hyphae that are 2–4 μm in diameter, often with swollen, rounded areas between septa.11 Spherical forms may be brown and thick walled; however, they lack the longitudinal and transverse septa characteristic of the sclerotic bodies of chromomycosis.2,11 Chytridiomycosis, a mycotic infection that has recently been demonstrated to cause disease in amphibians, is another possible differential diagnosis for the presence of round to oval structures. The structures associated with this disease are fungal cell bodies known as thalli, which contain multiple discrete, 2–3 μm in diameter round to oval basophilic spores. Empty thalli also can be seen.12 Sclerotic bodies are not observed in chytridiomycosis.