CONCURRENT MEDICAL CONDITIONS AND LONG-TERM OUTCOME IN DOGS WITH NONTRAUMATIC INTRACRANIAL HEMORRHAGE

Work was done at: Davies Veterinary Specialists, Manor Farm Business Park, Higham Gobion, Hitchin, SG5 3HR, England and Animal Health Trust, Centre for Small Animal Studies, Newmarket, Suffolk, CB8 7UU, England.

Abstract

Nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage is bleeding originating from the brain or surrounding structures. It results from blood vessel rupture and may be primary or secondary in origin. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) characteristics of 75 dogs with nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage were reviewed to determine signalment; intracranial compartment involved, size and number of lesions; type and prevalence of concurrent medical conditions; and long-term outcome. Hemorrhagic lesions were intraparenchymal (n = 72), subdural (n = 2) or intraventricular (n = 1). Thirty-three of 75 dogs had a concurrent medical condition. A concurrent condition was detected in 13 of 43 dogs with a single lesion ≥5 mm and included Angiostrongylus vasorum infection, intracranial lymphoma and meningioma. Of the 20 dogs with multiple lesions ≥5 mm, 7 had A. vasorum infection, 2 had hemangiosarcoma metastasis, 5 had suspected brain metastasis, and 1 was septicemic. Of the 12 dogs with multiple lesions, 2 had hyperadrenocorticism, 2 had chronic kidney disease, and 1 had hypothyroidism. Of these five dogs, all were hypertensive and four died within 12 months. No dog had a single lesion <5 mm. Long-term outcome was favorable in 26 of 43 dogs with single lesions ≥5 mm, 6 of 20 dogs with multiple lesions ≥5 mm, and 8 of 12 dogs with multiple lesions <5 mm. A. vasorum infection was the most common concurrent condition in dogs with nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage (16/75), with an excellent outcome in 14 of 16 dogs. Prognosis in nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage is reported in terms of concurrent medical conditions and the number and size of lesions. © 2012 Crown copyright. This article was written by M. Lowrie, F. Llabrés-Diaz and L. Garosi of Davies Veterinary Specialists and L. De Risio and R. Dennis of the Animal Health Trust. It is published with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland

Introduction

Cerebrovascular disease is a pathologic brain process resulting in compromised blood supply. A cerebrovascular accident or stroke is the most common clinical presentation of cerebrovascular disease, and is characterized by acute neurologic signs persisting for more than 24 h. Strokes can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. Ischemic stroke is more common, accounting for approximately 80% of all human strokes.1 Canine ischemic stroke carries a fair prognosis, although a concurrent medical condition increases the likelihood of subsequent infarcts and results in a less favorable prognosis.2

Hemorrhagic stroke is typically associated with vessel rupture or a coagulopathy, leading to extravasation of blood and an intraaxial hematoma or diffuse infiltrate within the neuropil or an extraaxial hematoma in the intraventricular, subdural or subarachnoid space.3 This may cause an increase in cerebral volume, brain edema, brain herniation, ischemia, brainstem compression, and development of deep pontine hemorrhages.4 Hemorrhagic stroke occurs in approximately 20% of human stroke patients.1 The incidence and prognosis of hemorrhagic stroke in dogs is unknown.

Nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage in dogs occurs from primary and secondary causes. Primary nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage is bleeding resulting from spontaneous rupture of penetrating vessels in the absence of vascular malformation or coagulopathy. In people it is attributed commonly to hypertension or amyloid angiopathy and accounts for 10% of all intravascular events.5 Hemorrhage secondary to hypertension occurs rarely in dogs6, 7 although cerebral amyloid angiopathy has been documented in a population of older dogs.8 Secondary nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage is the result of a vascular abnormality, coagulopathy, or hemorrhagic conversion of an ischemic stroke or tumor. Causes of secondary cerebral hemorrhage reported in animals include primary6, 9-13 and secondary14, 15 brain tumors; disseminated intravascular coagulopathy,16, 17 bacterial infection,18 Angiostrongylus vasorum infection;19, 20 hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic lesions;21 congenital vascular malformations;22-24 acquired vascular malformations;25 necrotizing vasculitis;26 and brain atrophy causing tearing of blood vessels leading to subarachnoid or subdural hemorrhage, for example, in storage disorders.27

In people, multiple small hemorrhages, termed cerebral microbleeds, appearing as small (<5 mm) focal hypointensities on T2* gradient-echo (T2*-GRE) sequences, occur in association with hypertension, aging, and ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.28, 29 These small hemorrhages are small focal deposits of blood breakdown products adjacent to histologically abnormal small vessels, resulting from blood leakage through fragile vessel walls.28 Their significance is uncertain but they may be the result of small vessel disease and some consider them to be a distinct entity compared to hemorrhages ≥5 mm.30 Multiple small cerebral hemorrhages <5 mm have been described in dogs.31

So far, studies on canine nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage involve patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis.6, 9-15, 22-27 Therefore, these reports are skewed toward individuals with a poorer prognosis. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based study offers a broader assessment, reduces bias, and allows identification of concurrent medical conditions. This is important as the concurrent medical conditions and outcome associated with nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage in dogs have not been characterized. Therefore, our aims were to evaluate dogs with nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage to determine signalment, size and number of lesions, intracranial compartment involved, type and prevalence of concurrent medical conditions, and long-term outcome.

Materials and Methods

The records of dogs that underwent MRI of the head at two veterinary referral institutions between January 2005 and August 2010 were reviewed. Only dogs undergoing MRI within 7 days of presenting with neurologic signs were included. Dogs had to have newly diagnosed intracranial hemorrhage and follow-up information for at least 6 months or until death. Patients with trauma were excluded. The location of the hemorrhage on MRI had to be consistent with the clinical neurolocalization.

Signalment, onset, progression and duration of signs, results of neurologic examinations, and concurrent medical conditions were recorded. Concurrent medical conditions were evaluated in all dogs by means of a complete blood count, serum biochemical panel, adrenal and thyroid function testing, urinalysis, indirect arterial blood pressure measurement, Baermann fecal examination, thoracic radiographs, and abdominal ultrasound. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was only performed if the attending clinician was not concerned about increased risk of collection. If a concurrent medical condition was not identified based on these investigations then coagulation profiling and cardiac ultrasound were performed. Results from histopathologic and postmortem examination were recorded when performed.

Thyroid function assessment included a minimum of total serum thyroxine (TT4) and serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) quantification. Adrenal function testing consisted of an ACTH stimulation test, low dose dexamethasone suppression test, or both. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were reviewed when available. Noninvasive systolic blood pressure measurements were recorded from conscious patients and values were only acceptable when determined as per the ACVIM consensus guidelines.32 Hypotension was defined as systolic pressure ≤90 mmHg and hypertension was defined as systolic pressure ≥180 mmHg.32 Coagulation profiles included a minimum of platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). D-dimers results were recorded when performed.

MRI was performed on either a 0.4T1 or a 1.5T2 magnet. The examination consisted of a minimum of transverse, sagittal and dorsal T2-weighted images, transverse T2-FLAIR, transverse T1-weighted images before and after intravenous paramagnetic contrast medium injection, and a transverse T2*-GRE sequence. Intracranial hemorrhage was defined as a hypointense lesion on T2*-GRE images. Dogs were included only if >50% of the cross-sectional area of the lesion was hemorrhagic. This was done to exclude large nonhemorrhagic lesions with small hemorrhagic foci.

The intracranial compartment containing hemorrhage was classified as intraparenchymal, intraventricular, subdural or subarachnoid. The characterization of intraparenchymal and intraventricular hemorrhage is straightforward. Subdural hemorrhage was defined as a crescent-shaped or medially concave mass not limited by suture lines and confined only by dural reflections such as the tentorium cerebelli or falx cerebri.33 Subarachnoid hemorrhage, in contrast, was limited by the arachnoid trabeculae that connect the arachnoid mater to the pia mater and therefore hemorrhage in this location did not expand the subarachnoid space.34

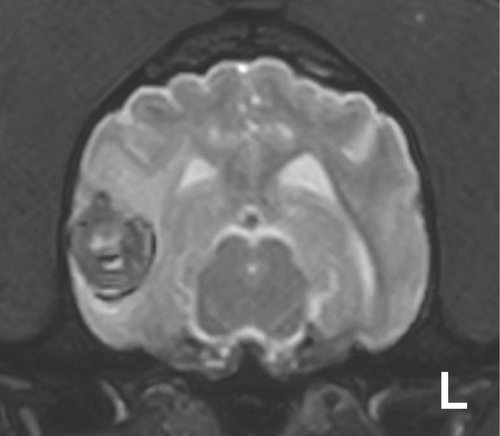

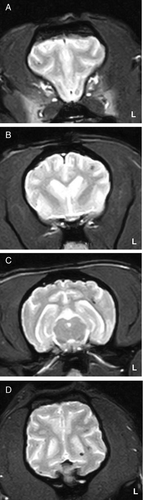

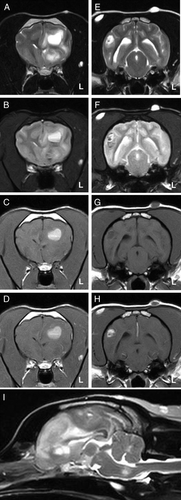

Lesions were divided into two groups based on whether they were single or multiple, and then were subdivided further according to whether the lesion(s) measured <5 mm or ≥5 mm on T2*-GRE images. This was done because cerebral hemorrhages <5 mm and ≥5 mm are considered to be distinct entities in people.30 (Figs. 1-3).

Long-term outcome, evaluation for more than 6 months following diagnosis or until the date of death, was recorded. Follow-up information was obtained by telephone consultation with the owner and/or referring veterinarian and combined with information from medical records. Outcome was graded excellent if the dog had returned to normal; good if the dog improved from first diagnosis but was still abnormal and poor if the dog had failed to improve, suffered recurrent neurologic signs or was euthanazed. Dogs that died within six months of imaging were considered to have a poor outcome. For dogs in which seizures were the sole clinical presentation, a poor outcome was assigned to those dogs in which seizures occurred with a frequency of more than one per month, or if status epilepticus or cluster seizures were present. However, if seizure frequency was less than one per month, with or without antiepileptic medication, then a good outcome was assigned.

Results

Seventy-five dogs were identified. Forty-two were male (22/42 neutered) and 33 were female (29/33 neutered). Median age was 9 years (range: 1–15 years). There were 34 different breeds. Seventy-two of 75 dogs had intraparenchymal hemorrhage (72/75) one had intraventricular hemorrhage, and two had subdural hemorrhage. Hemorrhage occurred in the telencephalon (60/75), thalamus/midbrain (2/75), cerebellum (3/75), or was multifocal (10/75).

Forty-three dogs had single hemorrhagic lesions. Thirty-eight had a lesion in the telencephalon, two had a lesion in the thalamus/midbrain and three had a lesion in the cerebellum.

Thirty-two dogs had multiple lesions. Twenty-two of 32 dogs with multiple lesions had disease confined to the telencephalon while the remaining 10 had multifocal disease; all of which had telencephalic involvement plus lesions in at least one other neuroanatomic region.

All single lesions were ≥5 mm in size. Multiple lesions <5 mm in size were seen in 12 of 32 dogs whereas multiple lesions ≥5 mm in size were seen in 20 of 32 dogs. No dog had multiple lesions that measured both ≥5 mm and <5 mm. A concurrent medical condition was identified in 31 of 75 dogs (Table 1).

| Lesion Type | Concurrent Medical Conditions |

|---|---|

| Single NTIH ≥5 mm Lesions (43/75) | Angiostrongylus vasorum infection (9) |

| Intracranial angiotropic T-cell lymphoma (1) | |

| Meningothelial meningioma (1) | |

| No concurrent medical condition identified (32) | |

| Multiple NTIH ≥5 mm Lesions (20/75) | Angiostrongylus vasorum infection (7) |

| Suspected primary extracranial neoplasia with suspected metastases to the brain (5) | |

| Confirmed primary splenic hemangiosarcoma with suspected metastases to the brain (2) | |

| Bacterial septicemia (1) | |

| No concurrent medical condition identified (5) | |

| Multiple NTIH <5 mm Lesions (cerebral microbleeds; 12/75) | Hyperadrenocorticism + hypertension (2) |

| Chronic kidney failure + hypertension (2) | |

| Hypothyroidism + hypertension (1) | |

| No concurrent medical condition identified (7) |

Eleven of 43 dogs with a single lesion had a concurrent medical condition, the most common of which was A. vasorum infection (9/43). Of two dogs undergoing postmortem examination, one had angiotropic T-cell lymphoma and the other meningioma. Two dogs had a presumptive large ischemic lesion with hemorrhagic transformation, but no concurrent medical condition. Hemorrhagic transformation was diagnosed based on T2-hyperintensity confined to a vascular territory.35 Thirty-two of 43 dogs with a single lesion did not have a concurrent medical condition.

Of 20 dogs with multiple lesions ≥5 mm, 15 had a concurrent medical condition. Two had a splenic hemangiosarcoma with presumed brain metastasis, five had multiple lung (1/5) or splenic (4/5) masses, but histopathologic evaluation was not performed. One dog had septicemia and seven had A. vasorum infection.

Of 12 dogs with multiple masses <5 mm, five had a concurrent medical condition. Two had azotemia and low urine specific gravity, two had hyperadrenocorticism and one was hypothyroid. All five of these dogs were hypertensive.

Of the 16 dogs with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection, a coagulopathy was present in five dogs based on an elevated PT, or elevated aPTT. D-dimers were measured in 4 dogs having elevated PT and/or PTT and these were elevated in 2. Mild thrombocytopenia was present in 2 dogs. Overall, 11 of 16 dogs with A. vasorum infection did not have a coagulopathy.

Three dogs underwent postmortem examination. Of these, two had a single lesion ≥5 mm and one had multiple lesions ≥5 mm. Dogs with a single lesion had intracranial angiotropic T-cell lymphoma and hemorrhagic meningothelial meningioma while the dog with multiple lesions had septicemia originating from the lungs.

Long-term follow-up ranged from 6 to 51 months (median, 22 months; Table 2). Long-term outcome in dogs with a single lesion ≥5 mm was good or excellent in 26 of 43 (60%); outcome was excellent in 16 dogs, good in 10 dogs, and poor in 17 dogs (Table 2). Nine dogs with a good outcome had continued seizures. Of the 17 dogs with a poor outcome, 2 with A. vasorum infection died because of the severity of the neurologic status, 14 died or were euthanized because of the severity of their neurologic status and one remained the same with bilateral central blindness, mild tetraparesis and cluster seizures.

Of the 20 dogs with multiple lesions ≥5 mm, outcome was excellent in six and poor in 14. All six dogs with an excellent outcome had A. vasorum infection. The 14 dogs with a poor outcome were euthanazed due to the severity of their neurologic status immediately or shortly following imaging.

Of the 12 dogs with multiple lesions <5 mm, outcome was excellent in 3, good in 5 dogs and poor in 4. The three dogs with an excellent outcome had no concurrent medical condition. The five dogs with a good outcome included one with hypothyroidism and hypertension and four with no concurrent medical condition. They all had recurrent generalized seizures. Of the 4 dogs with a poor outcome, two had chronic kidney disease and 2 had hyperadrenocorticism. Overall, 8/12 (66%) dogs with multiple lesions <5 mm had a good or excellent outcome.

| Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Type | Excellent | Good | Poor |

| Single NTIH ≥5 mm Lesions (43/75) | Angiostrongylus vasorum infection (7)No concurrent medical | No concurrent medical condition identified (10 – including one dog with an ischemic lesion with hemorrhagic transformation) | Angiostrongylus vasorum infection (2)Intracranial angiotropic T-cell lymphoma (1) |

| condition identified (9) | Meningothelial meningioma (1) | ||

| No concurrent medical condition identified (13) | |||

| Multiple NTIH ≥5 mm Lesions (20/75) | Angiostrongylus vasorum infection (6) | N/A | Suspected primary extracranial neoplasia with suspected metastases to the brain (5) |

| Confirmed primary splenic hemangiosarcoma with suspected metastases to the brain (2) | |||

| Bacterial septicemia (1) | |||

| Angiostrongylus vasorum infection (1) | |||

| No concurrent medical condition identified (5) | |||

| Multiple NTIH <5 mm Lesions (cerebral microbleeds; 12/75) | No concurrent medical condition identified (3) | Hypothyroidism + Hypertension (1) | Hyperadrenocorticism + hypertension (2) |

| No concurrent medical condition identified (4) | Chronic kidney disease + hypertension (2) | ||

Discussion

MRI is the gold standard for imaging intracranial hemorrhage in humans.36 The signal characteristics of hemorrhage are determined by the paramagnetic effects of the breakdown products of hemoglobin, magnetic field strength, pulse sequence and other technical and biological factors.37 As a hematoma ages it becomes less oxygenated with intracellular oxyhemoglobin converting first to deoxyhemoglobin and then methemoglobin within the first few days following hemorrhage.38 Erythrocytes then lyse due to utilization of remaining glucose reserves, releasing methemoglobin that is broken down by macrophages into ferritin and hemosiderin. While conventional T1- and T2-weighted sequences are fairly sensitive for the detection of blood, they are not specific. Alternatively, hemorrhage can be detected accurately using T2*-GRE pulse sequences that are sensitive to static magnetic field inhomogeneity.39-41 Hypointensity on T2*-GRE sequences is not specific for hemorrhage and can be seen with mineralization, gas, fibrous tissue and iron deposits although it offers enhanced sensitivity compared to spin echo sequences at standard field strengths for detecting hemorrhage.42

One dog (Fig. 3) with multiple lesions ≥5 mm and A. vasorum infection had multiple regions of signal void on a T2*-GRE sequence compatible with hemorrhage plus a separate lesion (Fig. 3, images A–D) that was hyperintense on a T2*-GRE and precontrast T1-weighted sequence. Causes of an increased signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences include methemoglobin, fat, proteinaceous fluid, melanin, calcification, paramagnetic substances such as iron or manganese and necrosis.20, 39, 43-47 It is possible this imaging feature is compatible with necrosis.47 However, the presence of a fluid line and the acute history of neurological signs that resolved with an excellent outcome following treatment for A. vasorum infection implicates hemorrhage. T2*-GRE sequences are not 100% sensitive to the detection of all stages of intracranial hemorrhage because, following erythrocyte lysis, methemoglobin moves into the extracellular space and becomes distributed homogeneously in plasma. Thus, the magnetic field within the voxel also becomes homogeneous causing loss of the susceptibility artifact.48

We dichotomized hemorrhagic lesions according to size into those measuring ≥5 mm vs. those <5 mm. This was based on the observation in people of hemorrhagic lesions of these sizes arising from distinct mechanisms.30 Multiple lesions <5 mm are seen in people due to small-artery diseases.28 The importance of such lesions is yet to be fully understood although histopathologic data supports a correlation with small vessel disease, notably cerebral amyloid angiopathy.29 The occurrence of multiple hemorrhagic lesions <5 mm in dogs is not characterized completely.8, 31 Nine dogs with multiple lesions <5 mm have been described, including four patients with neurologic signs.8 Histopathologically, there was cerebral vessel amyloid angiopathy in six of the nine dogs. It was hypothesized that amyloid deposition resulted in weakness of the cerebral vessels and concurrent medical diseases may have exacerbated this resulting in intracranial hemorrhage. Neurologic and imaging findings were described in four dogs with multiple lesions <5 mm.31 The imaging findings were similar to ours, and in one dog having histopathologic evaluation of the lesions, there were cavitated areas containing extravasated erythrocytes and numerous hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Unfortunately no dog in our study with multiple lesions <5 mm underwent postmortem examination.

Hypertension is commonly seen in association with multiple hemorrhages <5 mm in people29 which is similar to our results where hypertension was present in 5 of 12 dogs with such hemorrhages. Furthermore, hypertension was only seen in dogs with hemorrhages <5 mm and this conveyed a poorer prognosis than in normotensive dogs.

We used two magnetic field strengths, 0.4 T and 1.5 T although small hemorrhages were detected at both. Susceptibility artifact distortion is proportional to magnetic field strength.48, 49 Therefore, the actual size of the hemorrhages may have varied between scanners as the size of the susceptibility artifact was larger at 1.5 T. However, categorization of lesion size was only performed to distinguish lesions larger or smaller than 5 mm and all dogs in this study fell comfortably within one of these parameters. Without the addition of a T2*-GRE sequence in the 12 dogs with lesions <5 mm, the hemorrhages would have gone undetected as they were visible only on this sequence.

The concurrent medical conditions in dogs with nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage included A. vasorum infection, hypertension, metastatic hemangiosarcoma, chronic kidney disease, hyperadrenocorticism, intracranial angiotropic T-cell lymphoma, meningothelial meningioma, bacterial septicemia and hypothyroidism. The presence of any of these conditions in a patient with nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage does not mean that it was the cause of the hemorrhage. In certain instances the concurrent disease, such as A. vasorum infection19, 20 and metastasis,15 could be related to the hemorrhage.

Hypertension is the most important risk factor for development of nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage in humans.50 The identification of hypertension in our dogs was a poor prognostic indicator, with 4 of 5 patients relapsing between 3 and 12 months following diagnosis resulting in death or euthanasia. Systemic hypertension is a sequel to chronic kidney disease, hyperadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism and all five dogs with hypertension in this study had one of these conditions.51 It is possible that hypertension in these dogs predisposed to nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage. A similar relationship between hypertension and canine ischemic stroke has been observed.2

Angiostrongylus vasorum infection was the most common concurrent condition identified in dogs with nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage, because this parasite is endemic in the region where the dogs originated.19 The relationship between bleeding diatheses and A. vasorum infection is well known19, 20 with coagulopathy representing the second most common clinical manifestation of this parasite.52 We identified 11 dogs with A. vasorum infection that did not have a coagulopathy. The pathophysiology of the coagulopathy is not understood although disseminated intravascular coagulation, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia,53 von Willebrand factor deficiency16 and a decrease in coagulation factors V and VIII54 have all been seen in association with A. vasorum infection. It is suspected that the 11 dogs without a coagulopathy did have a bleeding diathesis and further investigations, such as buccal mucosal bleeding time, may have identified this.

Outcome in this study was reported relative to the number and size of lesions as well as any concurrent medical condition. Twenty-six of 43 (60%) dogs with single lesions ≥5 mm had a good or excellent outcome. The only concurrent condition in these dogs was A. vasorum infection. It is suspected that many dogs without a concurrent condition had a primary or secondary brain tumor, or a vascular malformation but this was not assessed at postmortem except in two patients that had meningothelial meningioma and intracranial angiotropic T-cell lymphoma. Six of 20 (30%) dogs with multiple lesions ≥5 mm had a good or excellent outcome. All these dogs had A. vasorum infection. Therefore the only diagnosis with a favorable outcome in dogs with multiple lesions ≥5 mm was A. vasorum infection. Eight of 12 (66%) dogs with multiple lesions <5 mm had a good or excellent long-term outcome. Hypertension was present in five of 12 (42%) dogs with such lesions and was always found in association with hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism, or chronic kidney disease. Four of five (80%) dogs with hypertension had a poor outcome. The lack of a concurrent condition in dogs with multiple lesions <5 mm led to good or excellent outcome in all dogs in this study.

The inclusion criteria for intracranial hemorrhage was hypointensity on T2*-GRE sequences. This criterion may have excluded some dogs with hemorrhage due to the variation in signal intensity as a function of hematoma evolution. Also, CSF analysis was not performed in every dog and this may have underestimated the prevalence of concurrent conditions.

Prognosis in nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage is reported in terms of concurrent medical conditions and the number and size of lesions. Concurrent conditions relating to single lesions ≥5 mm were most commonly associated with A. vasorum infection and neoplasia. Whereas concurrent conditions relating multiple lesions <5 mm were most commonly associated with endocrinopathies and hypertension. In dogs with multiple lesions ≥5 mm, A. vasorum was the only concurrent condition with a good outcome. Eighty percent of dogs with hypertension had a poor outcome. Long-term outcome was good to excellent in 61% dogs.

DISCLOSURE

None of the other authors of this paper has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of this paper