STOMACH WALL EVALUATION USING HELICAL HYDRO-COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Part of this study was presented at the 2010 ESVONC Annual Meeting, in Turin, Italy.

Abstract

In helical hydro-computed tomography (helical hydro-CT), water is used as a neutral luminal contrast medium together with intravenous iodine contrast medium for the diagnosis and staging of human gastric neoplasia. We evaluated the feasibility of helical hydro-CT in 11 healthy animals (nine dogs and two cats). Adequate uniform gastric distension was obtained with 30 ml water/kg body weight. Fourteen client-owned dogs and four cats with suspected or diagnosed gastric neoplasia then underwent helical hydro-CT followed by intravenous contrast medium administration. Focal thickening with moderate contrast enhancement was found in 10 dogs and 3 cats. The extent of the lesion was assessed easily in all these patients. Three dogs and one cat had a normal stomach wall. One dog had multifocal thickening of the antrum but no histopathologic diagnosis was made. Helical hydro-CT, followed by intravenous contrast medium administration, is a simple technique for assessing the stomach wall.

Introduction

In humans, the diagnosis of gastric disorders is done by means of endoscopy and double-contrast radiographic studies, which enable the detection of small-sized lesions. However, these techniques only allow visualization of the mucosa, thus preventing the assessment of transmural and extraserosal extension of disease. Additionally, these techniques cannot detect metastases, which makes them unsuitable for tumor staging.1 Therefore, transabdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and endoscopic ultrasound are preferred for staging, mostly being used in combination, as none of these modalities alone is sufficiently accurate.1, 2

Standard CT examinations are limited in their usefulness for the diagnosis of gastric cancer due to the presence of gas- and fluid artifacts and the difficulty of evaluating gastric wall thickening when the stomach is distended incompletely.1 The accuracy of CT in the diagnosis and staging of gastric cancer improves when helical CT of the stomach is performed after the oral administration of water. This procedure, which is termed helical-hydro CT, is followed by the intravenous injection of contrast medium to enhance the image of the gastric wall.1

In veterinary medicine, endoscopy and ultrasonography are used most commonly to evaluate gastric disorders.3 Sonographically, wall thickening and wall layer identification are key features for the detection and characterization of gastric lesions, particularly to differentiate inflammatory and neoplastic lesions. Commonly, the stomach is empty during the ultrasound evaluation, which precludes accurate assessment of wall thickness.4 Virtual endoscopy has not been widely assessed in companion animals and is not considered useful compared to conventional endoscopy.5

Our aims were to describe and optimize the technique for helical-hydro CT in dogs and cats and to evaluate the applicability of this technique in patients suspected of having a gastric tumor.

Materials and Methods

Nine healthy female adult crossbreed dogs and two healthy female domestic shorthair (DSH) cats were studied to optimize the technique. Their body weight ranged from 5 to 45 kg for the dogs and 3.5–4 kg for the cats. The animals were fasted for 15 h before the examination. They were anesthetized with intravenous diazepam, followed by intravenous propofol. After endotracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with isofluorane and oxygen.

A single slice helical scanner was used for the normal animal study1. All the animals were in sternal recumbency and scanned from the caudal border of the heart to the left kidney. The slice thickness was 3 mm and the pitch was 2:1. The animals were hyperventilated during the procedure to produce temporary apnea for the purpose of reducing motion artifacts. Four different volumes of tepid water (10, 20, 30, and 40 ml/kg) were given via a gastric tube, and CT images were acquired immediately after each volume was given. The whole procedure was performed over a period of 5 min to minimize gastric emptying between the different volume administrations. After the last water administration, the gastric tube was withdrawn partially and the CT study repeated after intravenous administration of 800 mg/kg of nonionic iodinated contrast medium with a power injector at 5 ml/s. Scanning was started about 30 s after the beginning of the contrast medium injection. All the studies were reconstructed with 1 mm slice thickness and reviewed using soft tissue and bone algorithms.

After the study of the normal animals, 14 adult dogs and 4 adult cats underwent helical-hydro CT. These 18 patients were all undergoing staging of confirmed (n = 11) or suspected (n = 7) gastric neoplasia. They were each given 30 ml/kg of water via gastric tube, which was considered appropriate based on the study on the normal animals. The patients were imaged before and after the administration of intravenous contrast medium (800 mgI/kg). Various scanners were used. These included a single-slice CT* in seven dogs and one cat, a 16-slice multidetector scanner2 in six dogs and three cats, and a 4-slice multidetector scanner3 in one dog. The slice thickness was 1.2–3.0 mm, depending on the machine. All the images of the normal and clinical animals were reviewed by a board certified radiologist (M.V.), who was unaware of the histopathologic diagnosis in patients for which it was available. The seven patients with suspected neoplasia underwent endoscopic biopsy (n = 6) or ultrasound-guided biopsy (n = 1) to confirm or to exclude the CT diagnosis.

Results

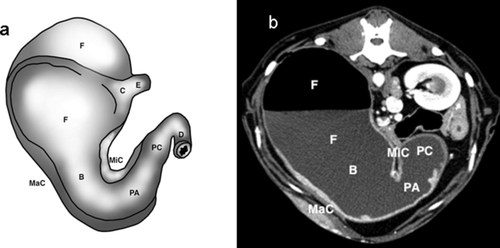

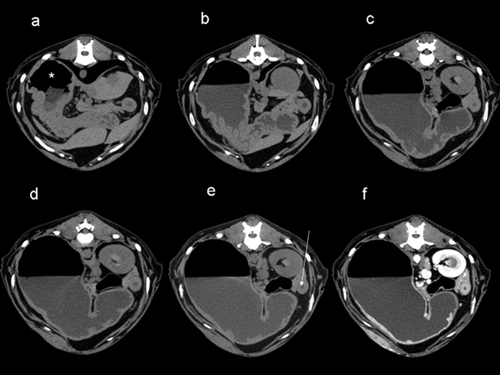

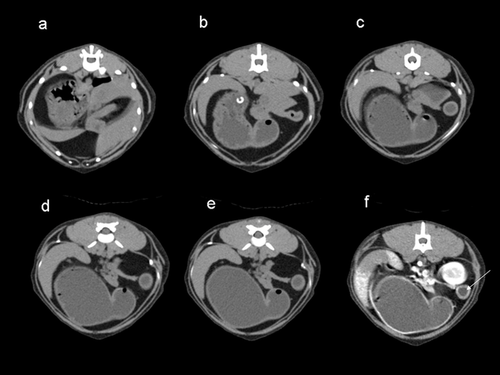

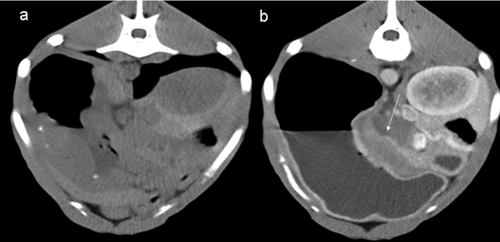

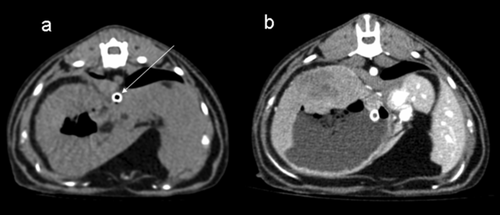

In the healthy dogs and cats, the stomach wall appeared thickened before water administration because the stomach was collapsed and the gastric lumen was poorly visible, if at all. After the administration of 10 ml/kg, there was insufficient distension of the gastric wall in all the dogs and cats. The fundus was slightly distended, but the body, pyloric antrum and pyloric canal were still collapsed, thus preventing evaluation of the wall. After 20 ml/kg, the gastric wall was thinner in all regions. However, in the pyloric part and at the junction between the body and the pylorus, pronounced stomach folds were still visible and in contact with each other. With a total volume of 30 ml/kg, gastric distension was satisfactory, even though small rugal folds were still visible in the pyloric region and at the body-pyloric junction. After 40 ml/kg, the stomach was distended and there were no rugal folds visible. All parts of the stomach could be assessed clearly with the 30 ml/kg and the 40 ml/kg distension. After intravenous administration of contrast medium, uniform moderate contrast enhancement of the gastric wall, especially of the mucosa, was observed (Figs. 1, 2A–F, and 3A–F). However, it was not possible to differentiate the layers of the gastric wall either before or after intravenous administration of the contrast medium. The comparison between the reconstructed images showed that the bone algorithm, despite its better spatial resolution, did not add further information.

Fourteen of the 18 patients with either histologically diagnosed or suspected gastric neoplasia had an abnormal gastric wall with helical-hydro CT. Further, histopathologic evaluation revealed gastric adenocarcinoma in eight dogs, low-grade leyomyosarcoma in one dog, and lymphoma in one dog and three cats. One dog with an abnormal gastric wall on CT did not undergo biopsy because of owner refusal. Three dogs and one cat originally suspected of having a neoplastic lesion on ultrasonography had a normal gastric wall on helical hydro-CT and neoplasia had been excluded on later histopathology.

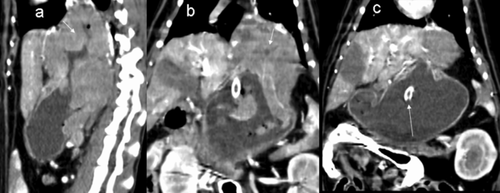

In the eight dogs with adenocarcinoma, the CT findings corresponded to a focal, moderate gastric wall thickening with inhomogenous contrast enhancement and hyperattenuating mucosa. The lesions were in the lesser curvature in five dogs, in the pyloric antrum in two dogs and in the fundus/body in one dog (Fig. 4A and B). The dog with a low-grade leiomyosarcoma had a discrete round mass filling almost all of the pyloric antrum and marked peripheral contrast enhancement. One dog with lymphoma had a moderate circumferential thickening of the gastric body and fundus with moderate inhomogenous contrast enhancement of the lesion and hyperattenuating mucosa. Of the three cats with lymphoma, one had moderate to severe gastric wall thickening at the cardias/fundus, another at the lesser curvature, and the third at the fundus/body (Fig. 5A–B). All three had moderate heterogeneous contrast enhancement of the lesion. One cat also had a hiatal hernia (Fig. 6A–C). In the dog that did not undergo biopsies, a multifocal thickening at the pyloric antrum was found, with marked contrast enhancement of the lesion and hyperattenuating mucosa.

Three dogs and one cat had a normal gastric wall on CT, thus excluding a neoplastic lesion. Multiple biopsies were taken of the stomach wall, and histopathologic evaluation confirmed the absence of neoplasia. In two dogs, the gastric lymph nodes were enlarged, and heterogeneous, and were found to be metastatic.

No adverse effects of the procedure were detected.

Discussion

Helical CT with water-filling of the gastric lumen followed by the administration of intravenous contrast medium has led to improvement in the detection and characterization of gastric cancer in humans6 and is the method of choice for preoperative imaging of gastric carcinoma.7 The main CT findings of gastric cancer are local or diffuse thickening of the gastric wall with variable contrast enhancement and an intraluminal soft tissue mass. Tumors can also infiltrate into perigastric tissue, encroach on adjacent organs and metastasize to distant sites.

We found that the wall of the normal collapsed, empty stomach appeared thickened before the administration of water, thus preventing the performance of reliable evaluation. After distension of the stomach with 30 ml water/kg body weight, all parts of the stomach could be satisfactorily assessed. The administration of intravenous contrast medium after the administration of water led to hyperattenuation of the mucosa in all normal dogs.

In the clinical patients, the thickening of the gastric wall on helical hydro-CT was highly indicative of a gastric tumor in 14 of the 18 patients, and the absence of thickening excluded a tumor in 4 of the 18 patients. Seventeen of 18 patients had the diagnosis confirmed by histopathologic examination. Intravenous contrast studies in the clinical patients were characterized mainly by heterogeneous contrast enhancement of the mass with a hyperattenuating mucosa. A specific pattern was not found that would have enabled differentiation of the different types of gastric tumors.

The intravenous contrast study is mandatory for tumor staging to assess the presence of metastasis in lymph nodes and various other perigastric organs. In humans, the accuracy of helical hydro-CT is acceptable for staging of distant metastasis, but inadequate for staging lymph node metastasis of gastric carcinoma.8 Helical hydro-CT also has a higher (86.0%) accuracy than that of conventional CT (72%) for staging gastric cancer.6 In this study, two dogs had enlarged gastric lymph nodes that appeared to be metastatic on cytologic examination. Nonetheless, helical hydro-CT is very useful for choosing between tumor resection and conservative treatment in patients with gastric tumors.

Helical hydro-CT can provide useful information about the location and extent of gastric lesions, as was shown in our study, and if surgery is an option. Helical hydro-CT is also valuable for excluding a gastric lesion suspected on other imaging modalities. In this study, three dogs and one cat suspected of having a gastric tumor on ultrasonography had a normal stomach on helical-hydro CT. However, the ultrasonographic studies were performed without dilation of the stomach by water, which may explain the different interpretation. However, it is more relevant to compare native ultrasonography with helical hydro-CT. The main advantage of ultrasonography compared to CT is that it can be performed with no, or less, chemical restraint. Having to anesthetize the patient to administer water for ultrasonography would clearly diminish the biggest advantage of this sonography in comparison with CT.

In veterinary medicine, the most frequent modalities used to study gastric lesions are ultrasonography and endoscopy.3, 4 Although we did not perform a direct comparison of these techniques with helical-hydro CT, we feel that hydro-helical CT could be superior to ultrasonography and endoscopy for evaluating the location and local invasiveness of the lesion. On the other hand, ultrasonography and endoscopy are probably superior for taking adequate biopsies.

Another possibility for dilating the stomach and studying the gastric wall more accurately with CT would be to fill the stomach with air. However, this technique cannot be standardized because it is not possible to predict or measure the quantity of air that escapes from the stomach. Additionally, the use of air carries the theoretical risk of vascular embolization or gastric volvulus. With the use of water, no complications were observed. Reasonable amounts of water simply pass through the stomach, as usual.

The images reviewed with a bone algorithm did not add further information, therefore it appears that a standard algorithm can be satisfactory for this technique.

In conclusion, helical-hydro CT is easy to perform and is useful for the diagnosis of gastric tumors in dogs and cats. The recommended dose of water is 30 ml/kg, and the hydro-CT study should be followed by the administration of intravenous contrast medium. Adequate distension of the stomach and optimally timed administration of intravenous contrast medium are mandatory to obtain high quality images and to detect and characterize the disease process.