COXOFEMORAL JOINT RADIOGRAPHY IN STANDING CATTLE

Abstract

The objective of this study was to establish a technique for radiographic examination of the coxofemoral joint and adjacent bony structures in standing cattle. Left (or right) 30° dorsal–right (or left) ventral radiographic views of the coxofemoral joint region of standing cattle (n = 10) with hind limb lameness were evaluated retrospectively. In addition, an experimental study of oblique laterolateral views of the coxofemoral joint region of a bovine skeleton at angles of 15–45° was carried out to determine the optimal position for visualization of the hip region. In the 10 clinical patients, the bodies of the ilium and ischium, the acetabulum and proximal third of the femur could be assessed. Six of these cattle had fractures of the body of the ilium and body of the ischium, five with and one without involvement of the acetabulum, two had craniodorsal and one caudoventral luxation of the femur and one had a femoral neck fracture. The described laterodorsal–lateroventral radiographs of the hip region in standing cattle were suitable for assessing the coxofemoral joint, the proximal aspect of the femur and parts of the ischium, ilium and pubis. After testing the optimal angle on the skeleton, it was seen that distortion and superimposition were minimized by positioning the X-ray beam at an angle of 25° to the horizontal plane. It can be concluded that the described technique improves the evaluation of injuries of the coxofemoral region in cattle. With the appropriate angle, the technique can also be applied in recumbent cattle.

Introduction

Diseases of the bovine coxofemoral joint are a diagnostic challenge. Clinical signs range from moderate and usually mixed hind limb lameness to inability to stand.1 Sedation or general anaesthesia is required to make pelvic radiographs of cattle and the required doses of radiation are very high with settings of 100 kV and 200 mAs.1-5 Furthermore, the procedure is time consuming and there is a risk of exacerbating existing fractures during the recovery phase. There are also drug withdrawal times to consider when sedating or anaesthetising cattle.

In 1991, a technique for obtaining standing equine pelvic radiographs was described.6 The X-ray tube was positioned ventrally under the abdomen of the horse and cranial to the pelvic limbs, and the cassette was placed dorsally on the sacrum. Good images of the iliac bodies were achieved with the X-ray beam at an angle of 20–25° to the vertical plane. With an angle of 30–35°, good images of the acetabulum and caudal pelvic region were obtained. The advantages of this technique compared with conventional methods were that the cranial parts of the acetabular rim and the coxofemoral joint space could be seen, sedation was not required in the majority of horses and the coxofemoral joint could be evaluated during weight bearing. A disadvantage was poor visualization of the caudal parts of the acetabular rim and the coxofemoral joint space. Settings of 150 kV and 400–500 mAs are required to obtain images of this region,5 which means that portable X-ray machines are not suitable. The long exposure time resulted in blurred images because of movement of the patient. This technique was not feasible in small horses and ponies because of limited space for the X-ray tube under the abdomen.

In 2006, another technique for obtaining pelvic radiographs in the standing horse was described.7 Laterodorsal–lateroventral views were made with the X-ray beam at a 30° angle to the horizontal plane. There was slight superimposition and only minimal distortion of the imaged structures of the coxofemoral joint farthest from the beam, the proximal third of the femur and the ilium and ischium. Thus, a variety of lesions involving these structures could be diagnosed, although many parts of the pelvis were not accessible.

This same technique has been used in our clinic for diagnosing diseases of the coxofemoral region in cattle since 2007. The goal of this retrospective study was to evaluate the quality of radiographs obtained using this technique with respect to location of the lesion and age of the cattle. The radiographic method was also assessed using a bovine skeleton to determine whether the technique could be standardized and/or improved.

Materials and Methods

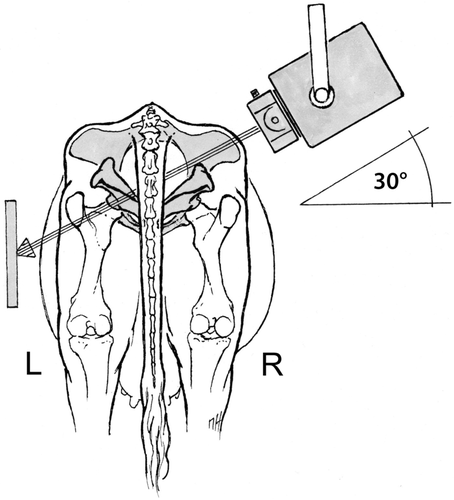

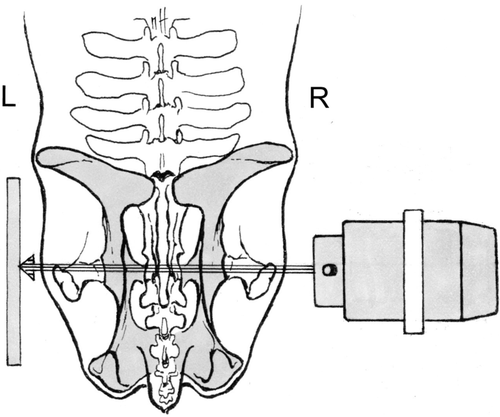

Ten cattle, including five mature cows (four Brown Swiss and one Red Holstein 560–630 kg) and five heifers (two Brown Swiss, two Holstein Friesian and one Red Holstein 300–350 kg) were evaluated between June 2007 and March 2011 because of pelvic limb lameness. Three animals were acutely lame and seven had been lame for more than 1 week. A mixed lameness was diagnosed in seven animals, supporting leg lameness in two and swinging limb lameness in one. Radiographs of the pelvis were made in standing animals with a movable overhead Siemens Polydoros 80 X-ray machine1 and CR cassettes2 with a linear grid, fixed in a cassette holder. The radiographs were made by various trained personnel using settings of 70–80 kV and 40–80 mAs. All radiographic views of the coxofemoral joint were laterodorsal–lateroventral views at an angle of about 30° to the horizontal plane (Figs. 1 and 2).

Radiographs were centered over the affected region, which was the left hip in seven animals and the right hip in three. Radiographs of the contralateral hip region were made for comparative purposes in three patients. Radiographs were evaluated by various radiologists, but all were assessed again by the same radiologist (RH) for this study.

A complete articulated bovine skeleton was used to determine whether the technique for pelvic radiography could be standardized and to establish the optimal angle for the X-ray beam in relation to the horizontal plane. A portable X-ray machine3 and a CR cassette were used with settings of 56 kV and 2.5 mAs. The cassette was positioned in a holding device with the cranial edge at the level of the coxal tuber. The angle of the X-ray tube and vertical placement of the cassette were the only variables. The X-ray tube was positioned at 15°, 22.5°, 25°, 30°, 37.5°, and 45° to the horizontal plane. The X-ray beam was directed from dorsal on the healthy side toward the affected coxofemoral joint ventrally (Figs. 1 and 2). The focus-to-film distance was 1 m.

Results

A fracture of the body of the ilium and body of the ischium with involvement of the acetabulum was diagnosed in five patients (Figs. 3 and 4), a fracture of the body of the ischium and ilium with no acetabular involvement in one other. Craniodorsal luxation of the femur was diagnosed in two cattle, caudoventral luxation in one. In one cow, fracture of the femoral neck (collum ossis femoris) was suspected, but the radiographic findings were inconclusive.

In all radiographs, the body of the ilium and body of the ischium had minimal overlapping and were assessed easily. The cranial branch of the pubis and the body of the ischium were seen adequately for evaluation in only three patients. The cranial branch of the pubis with the pectineal line was seen in only one patient. Assessment of the acetabulum was possible in seven patients; it could be differentiated easily from the surrounding bone mainly because of good visualization of the joint space. In contrast to the caudoventral luxation in one patient (Fig. 5) the acetabulum could not be identified clearly in the two patients with craniodorsal femoral head luxation. This precluded visualization of the joint space, which is critical for identification of the acetabulum. The greater trochanter, femoral head, proximal femoral metaphysis and the proximal part of the femoral diaphysis were seen readily and evaluated in all 10 patients. However, the neck of the femur could only be seen in the patient with a femoral fracture and in the two patients with craniodorsal femoral luxation because of slight rotation of the femur. In the remainder of patients, the greater trochanter and the neck of the femur were always superimposed. In addition, in the patient with a femoral fracture the distance between the femoral head and greater trochanter was reduced.

Eight of the 10 animals were slaughtered without treatment and one pregnant cow near term and in good general condition with only mild lameness of the affected limb was discharged with the recommendation to slaughter her after calving. One heifer with femoral luxation was operated using open reduction followed by stabilisation of the dorsal joint capsule with a mesh.8

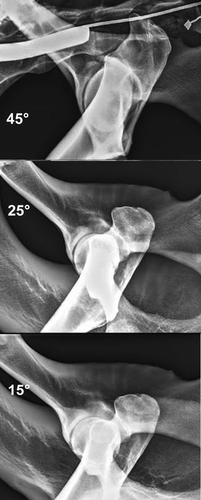

In laterodorsal–lateroventral radiographs of the pelvis of the bovine skeleton, there were various degrees of superimposition or distortion of the contralateral coxofemoral joint, proximal third of the contralateral femur and contralateral ilium and ischium, depending on the angle of the X-ray beam (Table 1). To position the coxofemoral joint centrally on the film, when an angle of 45° was used, the upper edge of the cassette had to be placed at the level of the palpable projection of the greater trochanter. It was necessary to increase the height at which the cassette was positioned as the angle of the X-ray beam decreased. Thus, to have the coxofemoral joint positioned centrally on the film when an angle of 15° was used, the upper edge of the cassette had to be placed approximately 5 cm ventral to the coxal tuber. With angles of 45° and 37.5° (Fig. 6), there was marked dorsoventral distortion and superimposition of the greater trochanter, ilium and sacrum. Superimposition and distortion were minimal with an X-ray beam angle of 25° or 30° (Fig. 6). Using an angle of 15° or 22.5°, there was superimposition of parts of the contralateral coxofemoral joint, body and acetabular branch of the ischium, with the ischial spine closest to the X-ray machine (Fig. 6). However, with an angle of 30°, the ischial spine was only partially visible and superimposition of the structures on the contralateral side was minimal. The least amount of distortion was achieved using an angle of 25°; at the same angle, the dorsal margin of the ischial spine closest to the X-ray machine was fully visible and not superimposed on the coxofemoral joint and bony structures dorsal to the joint on the contralateral side (Fig. 6).

| Angle of X-ray Beam | 15° | 22.5° | 25° | 30° | 37.5° | 45° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body of the ilium | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Ischial spine | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Body of ischium | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Branch and body of ischium | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Body with pecten pubis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Acetabulum | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Proximal femoral metaphysis | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Femoral diaphysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Femoral head | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Greater Trochanter | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

- 0 not assessable, 1 partially assessable, 2 assessable but distorted, 3 assessable.

Discussion

We have used a technique analogous to the one described for radiography of the pelvis in standing horses7 in cattle for a number of years. The ventrodorsal technique6 in standing animals is of limited use in lactating cows because insufficient penetration of the X-rays through the mammary tissue results in markedly reduced radiographic detail.

The technique used in mature cows in this study required less radiation (70–80 kV and 40–80 mAs) than a ventrodorsal view in dorsal recumbency in a horse (100 kV and 200 mAs) or a ventrodorsal view in a standing horse (150kV and 400–500 mAs). The muscle layers that were penetrated by the X-rays were less dense in the standing animal, especially in dairy cattle. Also, radiation exposure for personnel was minimal because a device was used to hold the cassette. Gas in the rectum created a contrast to the bony structures and increased the level of detail in laterolateral views. This can be achieved by manually removing faeces from the rectum just before radiography. Compared to conventional methods, obtaining oblique laterolateral radiographic views of the pelvis in the standing animal has a number of advantages. There is less input of time and decreased risk of exacerbating fractures or the clinical condition of the patient. In addition, sedation is not required in the majority of patients, which means that withdrawal times are not a limiting factor in cattle destined for slaughter because of a poor prognosis. The described method can also be used to obtain oblique laterolateral radiographs in downer cows. Downer cows are positioned in lateral recumbency with the cassette placed underneath the relevant acetabular area, and the beam is directed from dorsolateral at a 25–30° angle to a imaginary line through both coxal and ischial tubers.

Only the coxofemoral region closest to the X-ray cassette could be visualized on radiographs. Because most fractures of one side of the pelvis are accompanied by a fracture of the other hemipelvis, it is recommended to make radiographs of both sides, especially when treatment is planned.

The radiographic technique used in this study is a rapid method of evaluating diseases and fractures of the bony structures of the coxofemoral joint, body of the ilium, body of the ischium and proximal part of the femur. Fractures of the greater trochanter and proximal third of the femur as well as femoral luxations can be imaged optimally using an oblique view. The acetabulum could be readily assessed in patients with the femoral head in situ; however, in two patients with craniodorsal femoral luxation, superimposition of the displaced femur made assessment of the acetabulum difficult. Oblique views were inadequate for evaluating fractures of the pecten pubis, minimally displaced fractures of the femoral neck or the femoral growth plate. For diagnosis of these injuries, dorsoventral or ventrodorsal views may be indicated. For diagnosis of injuries of the sacrum, coxal and ischial tuber, additional horizontal laterolateral, tangential, ventrodorsal or dorsoventral views are required.

In our study, the location of the injury, but not the age of the patient, determined whether radiographs were of diagnostic value. However, the diagnosis of pelvic fractures in young calves can be difficult because of open growth plates, especially the three acetabular physes. Additional views, including those of the contralateral side of the pelvis are helpful for comparative purposes.

The radiographic diagnosis could be confirmed intraoperatively (femoral luxation) in one patient and at necropsy in four. The diagnosis based on clinical and radiographic findings could not be confirmed in the remaining five patients because they were slaughtered elsewhere with no opportunity for a postmortem examination; however, in four patients the fractures were palpable clinically and were visible on radiographs.

Positioning the X-ray beam at an angle of 22.5–30° produced the least distortion and least superimposition of the structures of interest on the contralateral ischial spine; the best radiographs with respect to these two factors were achieved using an angle of 25° to the horizontal plane. In a recent study a magnification technique was revisited and reapplied for radiography of various body parts using state of the art equipment to minimize the effects of superimposition.9 It may be possible to apply these principles to blur out the bony structures of one coxofemoral joint while obtaining images of diagnostic quality of the contralateral coxofemoral joint in cattle.

To avoid superimposition of the contralateral side, we recommend using an angle of 25° for evaluation of the coxofemoral joint and surrounding anatomic structures in standing cattle. In patients that do not stand squarely because of pain caused by a fracture, the pelvis may be skewed. In these patients, the correct angle of the X-ray beam is achieved using an imaginary line drawn through both coxal and ischial tubers for orientation and adjustment of the angle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff of the Division of Diagnostic Imaging and the Institute of Veterinary Pathology for their assistance and Matthias Haab for the illustrations.

REFERENCES

- 1 Siemens Schweiz AG, Dietikon, Switzerland.

- 2 ST5, Fujifilm AG, Dielsdorf, Switzerland.

- 3 Gierth HF 200, Gierth X-ray international GmbH, Riesa, Germany.