ULTRASONOGRAPHIC DIAGNOSIS—IDIOPATHIC MUSCULAR HYPERTROPHY OF THE SMALL INTESTINE IN A MINIATURE HORSE

No funding sources were used.

Signalment

Twenty-year-old, 115 kg American Miniature Horse gelding.

History

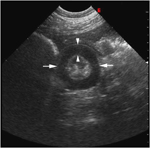

The gelding had been evaluated previously by us for chronic, intermittent colic, and mild weight loss. There were no significant findings on physical examination, abdominal radiographs, or gastroscopy. Severe annular thickening of multiple loops of small intestine and moderate peritoneal effusion (Fig. 1) were identified sonographically at that time. The thickening primarily involved the muscular layer of the small intestine. Differential diagnoses included neoplasia, idiopathic muscular hypertrophy, and severe enteritis; although, a nonvisible luminal and/or mural obstructive lesion could not be ruled out. A presumptive diagnosis of idiopathic muscular hypertrophy of the small intestine was made based on the absence of regional lymphadenopathy and lack of corroborating hematologic or serum biochemistry abnormalities for neoplasia or severe enteritis. Surgical exploration at that time was declined by the owner due to financial constraints. The gelding was discharged with instructions to feed a complete pelleted diet.

Transverse ultrasound image from the initial ultrasound examination. Note the thickened small intestine loop (arrows) found in the right caudoventral abdomen. The anechoic muscular layer (arrowheads) has symmetric annular thickening and measures 7.7 mm. Small intestinal loop diameter measures 2.8–3 cm. Minimal echogenic feed material is visible between the thickened and folded mucosal and submucosal layers. Image was obtained with a 4–8 MHz curvilinear transducer set at 7.5 MHz. Scanning depth=9 cm.

The clinical signs did not change, and the gelding was presented for reevaluation and possible exploratory celiotomy 10 months after the initial visit. When reevaluated, the gelding was mildly underweight but there were no other physical or laboratory abnormalities.

Abdominal Ultrasound

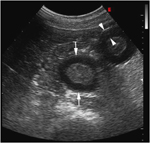

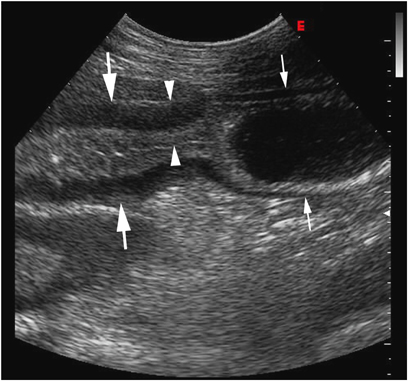

Several small intestine loops in the caudoventral abdomen were characterized by severe annular thickening. Wall thickness ranged from 5.8 to 13.2 mm with the majority measuring >8–9 mm. The muscular layer was most affected with symmetric thickening of 7.3–9.7 mm (Fig. 2). Segmental thickening was present with severely thickened loops continuous with mildly thickened loops (Fig. 3). Motility was markedly reduced within the severely thickened loops with minimal to absent luminal opening during peristaltic waves. No large intestine abnormalities were seen, and there was no evidence of regional lymphadenopathy. Moderate anechoic peritoneal effusion was seen in the cranioventral abdomen. Compared with the previous abdominal ultrasound examination, the bowel thickening had only slightly increased. There did not appear to be significant progression into previously unaffected small intestine based upon a similar location of abnormal small intestine loops within the abdomen. Differential diagnoses for the severe segmental annular thickening of the small intestine were unchanged from the initial exam; however, due to a subjective lack of progression into unaffected bowel in the 10-month interim, similar thickening of affected small intestinal loops between exams, and continued absence of visible enlarged cecal lymph nodes, idiopathic muscular hypertrophy remained the primary differential diagnosis.

Transverse ultrasound image of thickened small intestine loops (arrows) in the right caudoventral abdomen obtained 10 months after the image in Fig. 1. Note the similar degree of intestinal thickening. Small intestinal loop diameter measures 2.8–3.6 cm. The muscular layer (arrowheads) measures 7.3 mm. Image was obtained with a 2–5 MHz curvilinear transducer set at 4.0 MHz. Scanning depth=11 cm.

Longitudinal ultrasound image obtained 10 months after the image in Fig. 1. Note the segmental small intestinal thickening. Mild thickening (5.1 mm, small arrows) of the small intestinal wall with luminal distension is seen orad to severely thickened small intestine (large arrows). Maximal wall thickness is 13.2 mm (arrowheads). Image was obtained from the right inguinal region using the same technique as in Fig. 2.

Treatment

A ventral midline celiotomy was performed, and multiple, discrete segments of markedly thickened small intestine were identified extending from the mid-jejunum to proximal ileum. The affected segments were tubular and noncompressible, with segmental serosal hypervascularity. Each abnormal segment was approximately 15–30 cm in length and was separated from other segments by 30–75 cm lengths of comparatively normal bowel. The multifocal and extensive involvement necessitated en bloc resection of the 4-m segment of affected bowel, and an end-to-side jejunocecostomy was performed.

Routine postoperative medications were discontinued within 4 days of surgery, and the gelding was discharged 7 days after surgery. Twenty-eight months after surgery, the gelding had returned to his normal body condition and there were no signs of chronic colic.

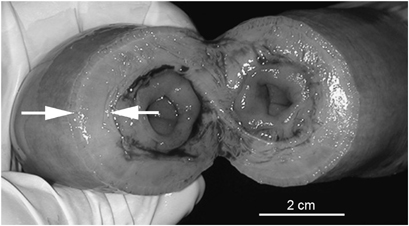

Histopathology

The segmental thickening of the intestine was caused by severe smooth muscle hypertrophy, primarily involving the internal circular layer of smooth muscle (Fig. 4). There was lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the lamina propria of the mucosa, and follicular hyperplasia of regional lymph nodes. The histopathologic diagnosis was chronic, severe, multifocal, segmental smooth muscle hypertrophy, and chronic, moderate lymphoplasmacytic enteritis.

Photograph of abnormally thickened small intestine, Note the severe muscular hypertrophy (arrows). The gross appearance correlates well to the ultrasound appearance of the bowel.

Discussion

Idiopathic muscular hypertrophy of the small intestine has been described in many species and occurs without mechanical obstruction as a stimulus for compensatory hypertrophy.1–4 Secondary hypertrophy can occur when an obstructive or stenotic lesion is present to predispose the orad segment to become hypertrophic.1,3 In this horse, idiopathic muscular hypertrophy was diagnosed because of the lack of an initiating obstructive lesion. Chronic, recurrent abdominal pain resulted from partial obstruction secondary to the reduced luminal diameter and decreased distensibility of the affected segment, which caused distension of the unaffected intestine orad to the lesion.

Idiopathic muscular hypertrophy of the small intestine in horses tends to involve the ileum1,2 and duodenum.4 Surgical bypass without resection has been used successfully for treatment.1,2 This patient was unusual in that multiple, separated segments of the jejunum and proximal ileum were involved, and the ileal segment was least affected. En bloc resection of the affected bowel was performed in this horse because of the extensive area involved and the concern that the multifocal involvement signaled a progressive lesion.

Abdominal ultrasound was critical in diagnosing the source of chronic, recurrent colic in this patient. The small size of this patient precluded use of rectal examination, which is an important diagnostic modality in evaluating colic in horses. Although abdominal ultrasound was not helpful in allowing identification of the cause of the muscular thickening, localization of the lesion to the muscular layer of the small intestine and the annular pattern of thickening helped prioritize the list of differential diagnoses.

Abnormalities of the small intestine are characterized by functional changes, such as reduced or absent motility and intestinal distension, and physical changes, such as increased wall thickness and loss of layering. Five intestinal wall layers may be identified in normal ultrasound images of the small intestine, with a normal wall thickness measuring 3 mm.5,6 These intestinal wall layers consist of a hyperechoic mucosal surface, hypoechoic mucosa, hyperechoic submucosa, hypoechoic muscularis, and hyperechoic serosa.6,7 Differentiation of intestinal wall layers can be difficult in equine patients, due to depth of penetration and attenuation of the ultrasound beam.6 Therefore, loss of layering is not as useful in guiding decision making in equine abdominal ultrasound as in smaller patients.6,7 In this patient, the increased wall thickness was associated with the muscular layer, which was consistent with the final diagnosis; however, partial disruption of the normal layered appearance, such as may occur with intestinal lymphosarcoma,7 could not be ruled out. Fortunately, supportive evidence in this patient included the uniform appearance of the annular thickening,6,7 absence of regional lymphadenopathy,5,6 and lack of progression in the 10-month interval between sonographic examinations.

This patient highlights the importance of ultrasound in evaluating problems originating from the abdominal cavity in horses. Abnormal findings that may be detected include identification of the site and severity of the problem, increased wall thickness, loss of symmetry or layering, characterization of intestinal contents, and regional or systemic involvement.6,7 In this patient, abdominal ultrasound accurately localized and characterized the nature and extent of the lesion, and there was excellent correlation between sonographic, surgical, and pathologic findings.