Regional Preferential Trade Agreements: Trade Creation and Diversion Effects†

This paper was presented at the Principal Paper session, “Trade Liberalization: Welfare Distribution and Costs,” Allied Social Sciences Association annual meeting, Boston, January 6–8, 2006.

The articles in these sessions are not subject to the journal's standard refereeing process.

There has been a significant increase in the number of regional preferential trade agreements (RPTA) since the 1950s. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) have been notified of 254 preferential trade agreements since 1948, with nearly half occurring after 1995. Many preferential trade agreements extend their coverage to agricultural commodities (Grethe and Tangermann; Tangermann and Josling). The European Union (EU), the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM), the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) are examples of such trade agreements. The EU recently expanded to include ten additional countries. In addition, the United States is negotiating with thirty-two Latin American countries to create the largest free-trade area in the world. While preferential trade arrangements are considered beneficial among the member countries, their effect on nonmember countries may be negative. This is especially true if a large number of countries are included in the agreement.

The main objective of this study is to examine the effects of RPTAs on agricultural trade. The paper focuses both on the benefits accruing to member countries (trade creation) and the negative impact on nonmember countries (trade diversion). Special attention is given to selected RPTA (e.g., ASEAN Free Trade Agreement [AFTA], Andean Community [CAN], EU, and NAFTA) and their effects on trade volume through trade creation and trade diversion. These effects of RPTAs are measured using a dummy-variable approach (Ghosh and Yamarik, 2002, 2004) in a gravity model framework (Anderson; Bergstrand, 1985, 1989).

Trade-Creation and Diversion Effects

An RPTA creates a free-trade area by eliminating trade barriers on goods between member countries. Thus, the agreement increases trade volume among the member countries through trade-creation and -diversion effects. Trade creation is defined as an increase in trade volume through the replacement of domestic products with low-priced imports from trading partners. Trade diversion is defined as an increase in trade volume through the replacement of imports from third countries with low-priced imports from trading partners in the free-trade area.

Under NAFTA, the United States increased imports of fruits and vegetables from Mexico where these products are cheaper to produce. This increase in imports of fruits and vegetables from Mexico is known as trade creation. On the other hand, the United States increased imports of textile products from Mexico by shifting its import source from China and India. Prior to NAFTA, China and India were lowerpriced suppliers of textile products to the United States than Mexico. NAFTA eliminated the U.S. import duties on textile products imported from Mexico, while maintaining duties on products from China and India. Therefore, Mexico became the lower priced supplier of textile products to the United States. This increase in imports of textile products from Mexico is known as trade diversion, which is harmful to nonmember exporters such as China and India.

Trade-creation and -diversion effects occur through interindustry trade and/or intraindustry trade. While interindustry trade can be trade-creating and trade-diverting, intraindustry trade tends to be more trade-creating. For example, the United States and Canada have similar resource endowments, while those between the United States and Mexico are less similar. As a result, the U.S. trade with Mexico under NAFTA tends to be interindustry. The United States is a capital- and technology-abundant country compared to Mexico, while Mexico is labor-abundant. Mexico, therefore, has a comparative advantage over the United States in producing labor-intensive commodities, such as leather and textile products, and will export them to the United States. The United States has a comparative advantage in producing capital-intensive goods, such as computers, automobiles, and aircraft, and will export these to Mexico. In addition, Mexico has a comparative advantage in producing tropical fruits and vegetables based on the differences in weather conditions. As a result, Mexico exports these products to the United States. On the other hand, the United States has a comparative advantage over Mexico in producing grains and oilseeds because of weather conditions and soil types and exports these products to Mexico.

Trade between the United States and Canada is better characterized as intraindustry based on increasing returns to scale (Krugman, 1980) and national product differentiation (Head and Riess). For example, in spite of similar resource endowments, trade volume between the United States and Canada has increased under NAFTA. This growth is not explained by differences in resource endowments (Heckcher-Olin theorem). Under the assumption that firms produce with increasing returns to scale technology, if countries seek to increase production and marketing efficiency, they do not produce the complete range of products individually. Countries will produce a few similar, but differentiated products to reach external or internal economies of scale and then exchange these products. Under intraindustry trade, producers benefit from improved production and marketing efficiency while consumers are given a wider range of product choices.

In the national product differentiation model, products are distinguished by country of origin, and the number of varieties supplied by each country is fixed. As a result, goods are differentiated by nationality even though they may be quite similar. The countries increase trade of similar products because goods are imperfectly substitutable. Under NAFTA, both monopolistic competition and national product differentiation have played an important role in explaining agricultural trade patterns between the United States and Canada.

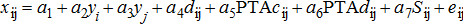

The Model

(1)

(1)The original gravity relation does not include other factors, Sij. However, many studies include them either because of theoretical considerations derived from other trade models (e.g., Aitken; Thursby and Thursby; Feenstra, Markusen, and Rose; Frankel and Rose; Harris and Mátyás; Ghosh and Yamarik, 2002, 2004) or because they believe the variables can help explain bilateral trade flows. Geographic factors such as countries sharing a common border, being landlocked, or located on an island are usually included. We also incorporate historical factors such as colonial history and common language, monetary factors including exchange-rate volatility and exchange-rate regimes, trade policy factors, per capita GDP or per capita income, and factors that measure relative factor endowment.

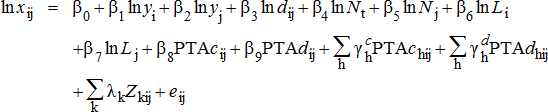

(2)

(2)A set of variables that is usually included in a gravity equation can potentially lead to an endogeneity problem. In particular, income and RPTA dummies, along with other variables, can be correlated with the error term. We do not expect this to be a significant problem in the case of agricultural trade because policies that affect GDP or a decision to form a RPTA are unlikely to be dependent on the volume of agricultural trade.

Data and Estimation Procedures

Cross-sectional data are used in the estimation. We use the latest available data for 1999. Data on agricultural trade flows were obtained from the World Bank Trade and Production Database. Since import data are generally more reliable than export data (Nicita and Olarreaga), we used mutual imports to calculate overall agricultural trade between each country pair. The WTO website provided information on current preferential trade arrangements. We accounted for 131 preferential trade arrangements reported to the WTO. Data on agricultural income (agricultural value added), population, land area, and gross domestic product were obtained from the World Development Indicator database maintained by the World Bank. The Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook was the source for data on common currencies, languages, landlocked countries, and border sharing. Distances between countries, measured between their capitals, were calculated using a computer program developed by John A. Byers that contained data on latitudes and longitudes of major cities in the world.

The use of cross-sectional data requires researchers to make adjustments to usual ordinary least squares (OLS) and instrumental variable (IV) estimators used to estimate the model since error terms in cross-sectional regressions tend to be heteroskedastic. The standard OLS and IV estimators produce unbiased estimates of regression coefficients. However, the estimates of the variance-covariance matrix are inconsistent in the presence of heteroskedasticity, therefore leading to incorrect test results. To correct for heteroskedastic bias in the variance-covariance matrix, we use White's estimator for OLS (see Greene) and IV regressions (see Baum, Schaffer, and Stillman).

Estimation of the Gravity Relationship for Agricultural Trade

RPTAs differ in their size and coverage. Their effect on agricultural trade is estimated in this analysis. Several regional trade agreements were chosen that are representative of different parts of the world, including the NAFTA and the CAN to represent the Western Hemisphere; AFTA to represent Asia; and the EU for Europe. Each of these RPTAs extends its coverage to agricultural commodities.

The effects of RPTAs are introduced in the model using dummy variables. We use a trade-creation dummy to see if common membership in one or several regional trade agreements generates more trade between countries, in addition to the trade predicted by a gravity relationship. Using a preferential trade dummy, we measure the trade effects of RPTAs on agricultural trade. If RPTAs generate positive trade, this can improve agricultural income provided agricultural trade and income are positively related.

We also measure the effects of nonparticipation in a RPTA using a trade-diversion dummy. This variable is expected to have a negative sign since trade is likely to be diverted from nonmember countries. However, there are several reasons why the trade-diversion dummy may have a positive sign. In this study, agricultural trade is highly aggregated. Therefore, if agricultural products traded with member and nonmember countries are not substitutes, increased trade with member countries from the preferential trade agreement may not preclude expansion of agricultural trade with nonmember countries. Also, agricultural products often constitute a small part of the wide variety of products and services included in preferential trade arrangements. Increased trade between RPTA members can generate an income effect, resulting in increased demand for imports from both member and nonmember countries.

Another explanation is that member countries of an RPTA may not maintain the same level of protection against exports from nonmember countries, thus allowing the transshipment of goods. Transshipped commodities may require an additional level of processing in a member country, which may not be sufficiently restrictive to discourage exports from nonmember countries. Finally, a trade-diverting dummy of a particular preferential trade agreement can be correlated with trade-creating dummies that are not explicitly accounted for if member countries participate in other trade agreements with nonmember countries. Inclusion of a trade-creating dummy that reflects the combined effect of preferential trade agreements mitigates this effect.

Table 1 presents the estimation results. Variables PTAcij and PTAdij represent the combined trade-creating and trade-diverting effects of RPTAs. The trade-creating and trade-diverting dummies isolate the effects of AFTA, CAN, EU, and NAFTA.

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | −26.763 | 1.324*** |

| Ln(GDPi) | 0.951 | 0.046*** |

| Ln(GDPj) | 0.938 | 0.043*** |

| Ln(Distanceij) | −0.872 | 0.068*** |

| Ln(Populationi) | −0.306 | 0.049*** |

| Ln(Populationj) | −0.312 | 0.063*** |

| Ln(Landi) | 0.191 | 0.039*** |

| Ln(Landj) | 0.185 | 0.041*** |

| Landlockedij | −0.796 | 0.141*** |

| Bordersij | 0.865 | 0.267*** |

| Currencyij | 0.6 | 0.218*** |

| Languageij | 1.116 | 0.155*** |

| Historyij | 0.639 | 0.212*** |

| PTAcij | 0.673 | 0.244*** |

| AFTAcij | 2.369 | 0.31*** |

| CANcij | 0.814 | 0.694 |

| EUcij | 0.24 | 0.278 |

| NAFTAcij | −1.224 | 0.843 |

| PTAdij | 0.42 | 0.167** |

| AFTAdij | 0.817 | 0.171*** |

| CANdij | −0.834 | 0.164*** |

| EUdij | 0.209 | 0.126 |

| NAFTAdij | −0.584 | 0.149*** |

- Notes: R2 = 0.646 Trade creation and diversion = 0; χ2(10) = 155.7 Trade creation = 0; χ2(5) = 102.5 Trade diversion = 0; χ2(5) = 76 Number of observations = 1,356

- *** significant at 1%

- ** significant at 5%

The regression results show that most traditional gravity variables have a statistically significant impact on agricultural trade. Countries' GDPs have positive and statistically significant impact on agricultural trade. The effect of the distance between countries was negative and statistically significant, suggesting that countries located close to each other will trade more. Population had a negative and statistically significant effect on agricultural trade. These results may suggest that larger countries would be less involved in international trade, replacing it with domestic commerce. The land-area variable had a statistically significant and positive effect on agricultural trade in most cases. A positive coefficient for the land-area variable is expected because; accounting for population and GDP, long distances within a country relative to the proximity of nearby countries may encourage international trade.

If countries do not have direct access to sea or ocean transportation, their ability to engage in agricultural trade is diminished. The coefficient of the landlocked variable was negative and statistically significant. If countries shared a common border, their bilateral agricultural trade tended to increase. Common currency, language, and colonial history also had a statistically significant, positive effect on agricultural trade, as expected.

On average, RPTAs had a positive and statistically significant effect on agricultural trade. The overall trade-creation coefficient was positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (table 1). The overall trade-diversion effect was positive and statistically significant at the 5% level. The trade-creation coefficient supports the hypothesis that, despite less coverage of agricultural commodities in preferential trade agreements compared to manufacturing products, the agreements create trade opportunities for agricultural producers. The positive effect of a trade-diverting dummy indicates that additional trade due to preferential trade arrangements does not necessarily divert trade with nonmember countries because agricultural products traded with member and nonmember countries may not be substitutes, thus not precluding agricultural trade expansion with nonmember countries. Preferential trade arrangements may stimulate demand for agricultural products from countries outside an arrangement by increasing countries' overall income. There is also a possibility of transshipments, due to nonuniform external trade protection levels in countries who are members of a preferential trade agreement.

The trade-creation effects of selected regional trade agreements were positive with the exception of NAFTA, but most were not statistically significant. The estimated trade-creation coefficient for NAFTA was negative but not statistically significant. Only AFTA had a statistically significant, positive impact on agricultural trade. This could occur because of a strong trade relationship resulting from close proximity (common borders). AFTA had the most prominent effect on agricultural trade, being four times higher than the average effect of all preferential trade arrangements. The trade-creating effect of the Andean agreement was slightly above average and the trade-creating effect within EU was below average, although neither was statistically significant.

CAN and NAFTA had negative and statistically significant trade-diverting effects, as expected. AFTA and the EU had positive trade-diverting effects, although the trade-diverting effect of the EU was not significant. This result may be explained in the same way as for an average trade-diverting dummy if those regional trade arrangements result in additional demand for imports from nonmember countries or traded agricultural products exhibit a low degree of substitutability. However, positive trade diversion effects in the case of a particular RPTA can simply proxy other preferential trade agreements with nonmember countries that were not explicitly included in the regression. The EU can be an example of the latter argument since EU member countries have preferential trade agreements with countries in Eastern Europe and North Africa.

The net effects of preferential trade agreements on agricultural trade, obtained by comparing trade-creating and trade-diverting effects, were positive overall. However, the Andean agreement and NAFTA were trade-diverting since these coefficients were negative and statistically significant and trade-creating coefficients corresponding to those agreements were not statistically different from zero.

Finally, we tested for the overall statistical significance of trade-creating and trade-diverting effects (table 1). The hypothesis that trade-creation and trade-diversion effects were zero was rejected at conventional statistical levels. The trade-creation effects were positive, as expected. However, the trade-diverting effects were also positive, although slightly smaller than the trade-creation effects. This may indicate that the demand-increasing income effect of RPTAs outweighs any trade-diversion effect.

Conclusions

The effect of preferential trade arrangements on agricultural trade were analyzed using a gravity model. The overall effects of RPTA are positive and significant, indicating that RPTAs, in general, increase trade volume among member countries through both inter- and intraindustry trade. The trade-creation effects of NAFTA were not significant, possibly because these countries already have a strong trade relationship as a result of their close proximity. The overall trade-diverting effect was positive, indicating that RPTAs do not displace agricultural trade with nonmember countries. One reason may be because of a low degree of substitutability between traded products. Another potential reason for this result is that the trade-creating effect of RPTAs could increase overall demand to such an extent that the income effect outweighs the trade-diversion effect of the agreements.

Although the benefits of RPTAs are greater for member countries than for nonmembers, the results of this analysis indicate that RPTAs are not harmful to nonmember countries. This suggests that RPTA improve global welfare by increasing agricultural trade volume among member countries and, to a lesser degree, among nonmember countries. This implies that, in general, RPTA are welfare enhancing with respect to agriculture for both member and nonmember countries.