Vertical Integration in Ecuador: The Case of Fresh-Cut Pineapples

Abstract

Telesignos, a fruit producer and exporter in Guayaquil, Ecuador, was considering vertical integration into pre-cut pineapple production. Fruit processing skills, favorable image/reputation, as well as access to a new market could be obtained by linking with a company like Del Monte to produce fresh-cut fruit products under the Del Monte brand. The decision is whether it would make sense for Telesignos to invest in a fresh fruit processing facility in Ecuador to export fresh-cut pineapple to the United States.

Carlos was relaxing in a chair while staring out at the Pacific Ocean. His home on the beach provided a breeze but humidity was a way of life in coastal cities like Guayaquil in Ecuador. He had a cold glass of Quito Orange drink made from naranjilla fruit that helped keep him refreshed.

For a long time, he had dreamed about vertically integrating his mango and pineapple fruit plantation and export business into further processing of pre-cut fruit. He was thirty-eight years old with five children and had a degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Hartford and a master's degree in agribusiness from Kansas State University. As CEO of Telesignos, he was constantly looking for new business opportunities. His business sold fresh fruit to brokers in various Caribbean countries and the United States. Moving into the pre-cut fruit market would require all of the company's capital and management expertise. It offered a great deal of potential because of the added value but there were risks involved in such a venture.

Telesignos was owned by four Ecuadorian investors. The company had acquired a plantation in 1993 and planted mangoes and pineapples. It owned about $1 million in assets and exported fresh mangoes to the United States, Canada, and the European Union. The pineapples were nearly ready to produce their first crop and Telesignos wanted to decide how to market the fruit.

Vertical integration into production of pre-cut fruit would permit Telesignos to capitalize on its potential growth opportunities. However, forward vertical integration required high capital investment, fruit processing skills, a favorable image, and access to new markets. The shareholders of Telesignos could provide the money to build a fresh fruit processing facility. The banking system in Ecuador had recently suffered from instability, so it would be difficult for Telesignos to borrow money from banks to pursue this venture. The other requirements could be obtained by linking with a company such as Del Monte (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2002) to produce fresh-cut fruit products to be sold under the Del Monte brand name. Pineapples and mangoes are two fruits that are suitable for fresh-cut products in Ecuador. The majority of mangoes are produced under contract and attaining enough fruit would be a problem. However, pineapples are in great supply and many are not being contracted. As such, Carlos had to decide whether it would make sense for Telesignos to invest in a fresh-cut pineapple processing facility in Ecuador to export to the United States.

The Fresh Fruit Industry

Carlos had gathered a great deal of information about the fresh pineapple (fruit) industry. There were many things to consider before becoming vertically integrated.

Production and Technology

Fruit usually produces one crop each year and is highly perishable. When yields are high, prices in export markets often drop to where it does not pay the producer to ship fresh fruit. High-yielding fruit crops depend upon the right weather conditions. Pests and disease detract from the cosmetic appearance of fruit. They also affect the overall yield of a plantation. Fresh fruit importers in export markets are looking for suppliers that have broad product offerings and year-round supply. Currently, Telesignos sells its fresh mangoes through brokers who receive high commissions. Supermarket chains and/or fresh produce importers will not buy direct from Telesignos unless the company can supply them with large quantities of a broad variety of fruits year round.

In recent years, differentiation has occurred among pineapples in the form of varieties. Del Monte introduced the MD-2 variety called “Del Monte Gold Extra Sweet Pineapple” into Costa Rica in the mid 1990s. This variety was immediately successful in the fresh pineapple market. Asian pineapples (excluding the Philippines) are primarily used for processing or juice whereas pineapples from northwest Africa, Latin America, and South America are used in the fresh market.

Potential growth opportunities arise from consumers in export markets wanting convenience foods like ready-to-eat fruits. Many consumers do not want to peel, core, and slice fresh fruit. Fruit that is trimmed, peeled, cut into a 100% usable product, and bagged or prepackaged offers consumers nutrition, convenience, flavor, and freshness. Carlos chose to focus on the fresh-cut pineapple due to its high fiber content that made it easier than mangoes to cut and retain its form.

Market Environment and Opportunities

Since the 1980s, the fresh-cut produce industry has enjoyed double digit growth rates. The International Fresh-Cut Produce Association estimated that the 1999 U.S. fresh-cut produce (e.g., fruit) market was as large as $10 billion annually (about 10% of total produce sales including retail and foodservice) and the segment was expected to more than double by 2005. Another study from the association found that 85% of consumers are buying fresh-cut produce with 76% purchasing it at least once a month. The growing number of immigrants from Latin America and southeast Asia are also important markets for fresh pineapple.

The fresh-cut produce industry is global as rival firms compete in many different countries. Competition is especially strong in countries where sales are large and volume is strategically important to building a strong global position in the industry. For example, Dole Food Co. (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2003b) distributes its fresh fruit and vegetables to more than ninety countries worldwide. However, sales by Dole in the United States and Japan accounted for 42% and 14% of their total worldwide sales, respectively, in 1999.

With only three firms holding a significant market share, the fresh-cut produce industry is concentrated. Dole Food Company, Del Monte Foods Company, and Chiquita (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2003a) brands are the largest firms. There are a number of other companies in this industry, although none with a substantial share of total industry sales or widespread buyer recognition. Buyers of fresh-cut produce include virtually every food retailer. Del Monte Foods markets its products to the U.S. military and food processors as well.

Wholesalers and retailers were consolidating and restructuring as the potential for new technology to extend economies of size contributed to the plethora of mergers and acquisitions. These new entities have become increasingly important produce buyers as a result. Recently, mass merchandisers have also become large produce buyers. For example, Wal-Mart accounted for more than 10% of Del Monte's sales in 1999.

The Fresh-Cut Fruit Industry

Carlos recognized that the fresh-fruit industry was different from the fresh-cut fruit industry.

Production and Technology

Production of fresh-cut fruit is accomplished with a variety of machines and methods that have different effects on product quality and yield. The market to which the fruit is sold determines the quality of product and type of packaging required.

When cutting fresh fruit, yield differs daily. The quality of the fruit entering the plant affects the portion of the fruit that can be utilized. Damaged skin requires special trimming, a reduction of yield and increased labor. The best quality fruit, in both appearance and flavor, results in high yield and an excellent finished product. Most machinery cannot duplicate the motion of the human hand and therefore cannot remove all the fruit flesh. The benefit of using machinery is the reduced exposure to human hands (and improved food safety) and increased efficiency and uniformity of the finished product. However, processing of some fruit requires human handling.

Sweetness, measured by the brix level, determines the best fruit for fresh-cut processing. Although the brix level is generally a good indicator of flavor, fruit with the highest brix levels is not always best for a fresh-cut product. A high brix level can indicate that the pineapple is too ripe, which leads to cutting and handling problems and shortened shelf life. Tropical fruits need to be firm and sweet to make high-quality fresh-cut product. The physiology of fruit makes shelf life and flavor retention management difficult.

Market Environment and Opportunities

Consumers desire fresh foods that are convenient and safe to eat. Advancements in technology enable processors to provide fresh-cut produce to consumers more efficiently using a process called modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), which extends product shelf life and better preserves product freshness. MAP achieves these benefits by reducing produce respiration rates, retarding biochemical ripening and aging reactions, slowing browning reactions of cut surfaces, and altering microbe population dynamics. However, MAP is not a substitute for temperature control (proper temperature controls throughout the cold chain must be in place), does not stop microbial growth (efficient sanitation practices and proper sanitizing equipment are required in the process), and does not improve the quality of poor product. In addition, fresh-cut processors implement quality programs, such as Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs), Sanitation Standard Operation Procedures (SSOPs), and Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP), which help achieve these goals.

Packaging designs of new products are often recloseable, reusable, recyclable, and some have more than one tamper-proof seal. In addition, packaging features very bright graphics with tropical colors to create eye-catching appeal and make products an impulse item. Fresh-cut fruit processors today market not only single-fruit products but also tropical fruit salad mixes.

Market Risks and Opportunities of Vertical Integration in the Fresh-Cut Fruit Industry

Carlos' plan was to vertically integrate into fresh-cut fruit production. However, there was a great deal of competition. Two main producers in this industry, Dole and Chiquita, had integrated forward into manufacturing, packing, transportation, and distribution. Backward integration into production of fresh produce generated cost savings and allowed these companies to offer their buyers the highest quality and widest variety of produce.

Del Monte Foods, a processor and packer, had also integrated forward into distribution. Integrating backward required radically different skills and business capabilities by Del Monte. Consequently, the company concentrated on canning and distributing produce. There are two basic types of distribution channels to access buyers of fresh produce: retail and foodservice. Forward integration into transportation and logistics is done through contractual relationships rather than actual ownership. Small companies are at a disadvantage because many Latin and South American countries such as Ecuador, have limited fast delivery services due to differing air regulations. Thus, companies in some countries that sought to export to the United States did not have the same access to logistical options due to differing policies. Table 1 describes the various activities associated with the value chain for fresh-cut pineapple.

| Value Chain Activities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchasing | Operations | Distribution | Sales & Marketing | Advertising & Promotion |

| Strict specifications on raw fruits and vegetables | Extending product shelf life, improved user convenience, enhanced product appearance | Fast delivery of finished product, handling of refrigerated products | Product attributes and convenience, freshness, and shelf life attributes | Brand extensions to product line of fresh and fresh-cut fruit |

Purchasing and procurement activities affect the performance or quality of a company's end product. For example, Del Monte is one of the best-known processed fruit, vegetable, and tomato brands in the United States partly because it has very strict specifications on the raw fruits, vegetables, and tomatoes it purchases. Contracting is important in attaining this raw fruit and vegetable quality. Higher-quality products begin with excellent raw material selection, time and temperature controls for raw and finished goods, and excellent sanitation practices. The modified atmosphere packaging of finished products also provides potential differentiation.

Telesignos could use the following to enter this new industry: acquisitions, strategic alliances such as joint ventures, and internal growth. Growth through acquisitions is the easiest way to enter an industry, but requires a strong balance sheet as debt capital is often used to acquire the assets. Strategic alliances such as joint ventures enable firms to share assets in an organization such as a limited liability company. This enables companies to share the costs of the new assets with one or more other firms and results in less capital being required. Often the partner in a joint venture is a local firm in another country who knows the industry in that country. However, it is difficult to build size and scale through a joint venture. Internal growth is another option, but using this approach is a lot slower as a startup venture is often smaller scale.

Del Monte Foods has grown through acquisitions and new product development. This type of growth was not only less expensive than building new facilities but was also faster. For example, in September 2000, Del Monte Foods paid over $14 million to acquire the Sunfresh brand (citrus and tropical fruits) along with a Texas-based distribution center from the UniMark Group. In addition, Del Monte acquired the S&W brand of canned fruits and vegetables, tomatoes, dry beans, and specialty sauces from Tri Valley Growers for over $40 million in early 2001.

There were some political risks that needed to be considered. For example, inflation was a big problem in Ecuador and it was increasing. The country had recently adopted the U.S. dollar as its currency, which helped stabilize the currency. However, it did not mean that the Ecuadorian consumer or producer had purchasing power parity with U.S. consumers and producers. Countries neighboring Ecuador, such as Venezuela and Colombia had unstable governments. Peru had recently defeated the rebels that had been engaged in a guerilla war with the government. Brazil had recently devalued its currency making Ecuadorian exports more expensive. Despite the political problems that surrounded Ecuador, much of its exports went to the United States with whom it had a strong relationship. Ecuador had never nationalized any assets other than a railroad over 100 years ago and this has since been privatized.

The Decision

The decision whether to enter a new market was crucial for Telesignos. Carlos was aware that a bad decision could put the company out of business. He began his research by analyzing the fresh-cut produce industry, estimating Telesignos' operating expenses as well as costs to build a processing facility.

He had already decided that it made sense to process only pineapples because mangoes had more watery pulp and would not retain shelf life. In addition, the demand for fresh-cut pineapple was much stronger. The plant would process pineapples because they retain flavor better and have a longer shelf life than other tropical fruits. He had the support of Del Monte and Dole, which had indicated that they would consider buying the pineapples if a plant was built. They did not own any assets in Ecuador at that time but were interested in expansion opportunities, especially since production of pineapples had increased in that country in recent years. A key concern was whether the supply of pineapples in Latin America and South America was growing faster than the U.S. demand.

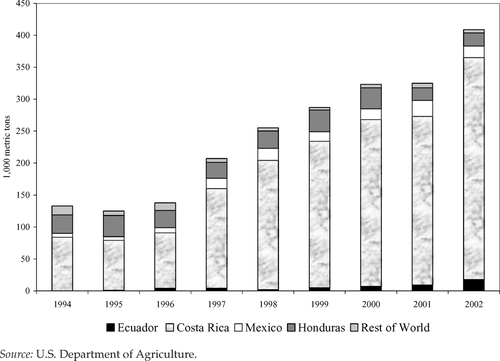

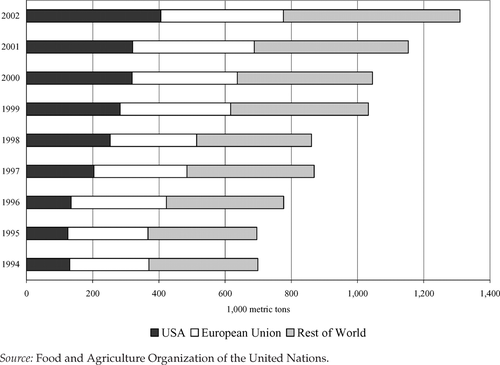

Pineapple production has increased in several Latin American countries since 1994, including Brazil, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela. In particular, Costa Rica was the major exporter to the United States while Ecuador had increased from an insignificant level to third highest (figure 1). In addition, total U.S. pineapple imports had been increasing faster than global imports (figure 2). The vast majority of U.S. imports were fresh whole pineapple (FAO). It was important for Carlos to understand why these trends had occurred and what these trends might mean for the future.

Table 2 contains a list of assumptions underlying the financial projections Carlos had developed. Several of these assumptions were important in determining the financial feasibility of the project. First, Carlos had assumed that the plant would only run ninety days during the first two years and then increase by thirty days every three years. The plant capacity would exceed the existing amount of land planted to pineapples to allow Carlos the opportunity to add more land as the business grew. A 65% cutting yield was assumed based on average industry yields. Production was assumed at eight hours per day with a fresh-cut fruit production rate of 450 kilograms per hour. Thus, total fresh-cut production in year 1 was 324,000 kilograms (e.g., ninety days multiplied by eight hours per day multiplied by 450 kilograms of fruit per hour). Consequently, 498,462 kilograms of raw pineapple were needed to run the plant (e.g., 324,000 kilograms divided by 65% yield).

| Year | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Data | |||||||||||

| Fresh-cut fruit production (kg/hour) | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 |

| Production day (hours) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Operation (days/year) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 180 | 180 |

| Fresh-cut fruit production (kg/year) | 324,000 | 324,000 | 324,000 | 432,000 | 432,000 | 432,000 | 540,000 | 540,000 | 540,000 | 648,000 | 648,000 |

| Yield (%) | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| Raw fruit consumption (kg/year) | 498,462 | 498,462 | 498,462 | 664,615 | 664,615 | 664,615 | 830,769 | 830,769 | 830,769 | 996,923 | 996,923 |

| Average raw fruit price ($/kg) | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 1.07 | 1.18 | |

| Average fresh-cut fruit price ($/kg) | 4.40 | 4.49 | 4.58 | 4.67 | 4.76 | 4.86 | 4.96 | 5.05 | 5.16 | 5.26 | |

| U.S. inflation rate (%) | 2 | ||||||||||

| Ecuador inflation rate (%) | 10 | ||||||||||

| Total hourly labor cost | 7.30 | 8.03 | 8.83 | 9.72 | 10.69 | 11.76 | 12.93 | 14.23 | 15.65 | 17.21 | |

| Total hourly utility cost | 14.49 | 15.94 | 17.53 | 19.29 | 21.21 | 23.34 | 25.67 | 28.24 | 31.06 | 34.17 | |

| Total packaging cost ($/kg) | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | |

| Shipping and handling cost ($/kg) | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.59 | |

| Fixed assets | |||||||||||

| Main building | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 | $312,686 |

| Process area | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 | $89,446 |

| Equipment | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 | $500,000 |

| Gross fixed assets | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 | $902,132 |

| Cash | $800,000 | $597,555 | $663,312 | $736,618 | $811,454 | $888,055 | $966,692 | $1,047,668 | $1,131,328 | $1,218,061 | $1,308,305 |

| Account payables (%) | 95.0 | 95.0 | 92.5 | 90.0 | 87.5 | 85.0 | 82.5 | 80.0 | 77.5 | 75.0 | |

| Working capital | $800,000 | $870,213 | $940,426 | $1,010,639 | $1,080,853 | $1,151,066 | $1,221,279 | $1,291,492 | $1,361,705 | $1,431,918 | $1,502,132 |

- Source: Piana.

Leading exporters of pineapples to the United States

Leading pineapple importers

It was difficult to estimate the price of fresh-cut or raw pineapples and companies like Del Monte did not have long-term contracts with a fixed price. The price of fresh-cut pineapples was the 1999–2000 average of $4.40 per kilogram (Piana) and was assumed to increase at the rate of inflation in the United States. The raw pineapple price was $0.50 per kilogram and was assumed to increase at the rate of inflation in Ecuador. This was a conservative estimate but it was one that was comfortable given that there were no reliable public data on prices of wholesale fresh-cut pineapple in Ecuador.

Total hourly labor costs and utility costs were estimated at $7.30 and $14.49, respectively, and increased at the rate of inflation in Ecuador. Total packaging and shipping and handling costs were $0.13 and $0.25 per kilogram, respectively. (The cost of shipping from Ecuador to Miami by ocean freight was $0.25 per kilogram compared to $30 per kilogram by air freight.)

Gross fixed assets were $902,132 and consisted of a $312,686 main building, $89,446 processing area, and $500,000 in equipment. Straight-line depreciation was assumed with a $200,000 salvage value for all gross fixed assets and a ten-year depreciable life for the buildings and equipment.

The project would be equity-financed due to the difficulty of obtaining debt capital in Ecuador and other Latin American countries. Carlos' investors required that 100% of the net income be paid in dividends each year. This environment caused Carlos to begin with an initial working capital of $800,000 in cash. The working capital requirements would likely increase as production increased. Carlos anticipated that his accounts payable policy would require a short payment period initially, which could be stretched after the processing plant was established (table 2). Based upon his fresh fruit business, he anticipated he would receive 80% of the sales in the year they were sold and the remainder the following year.

Other factors needed consideration. For example, Ecuador recently adopted the U.S. dollar as its official currency. Thus, Carlos' projections were based on his knowledge of prices and costs prior to the country's adoption of the dollar that had helped to reduce Ecuador's inflation rate. However, it also meant that it linked Ecuador's purchasing power to the relative strength of the U.S. dollar. Thus, some of his assumptions regarding costs might be understated if the Ecuadorian economy adjusts to the historical strength of the dollar.

Marketing fresh-cut fruit also meant bypassing food brokers because he would be in direct competition with large multinational companies. This was risky because these companies had more volume and longer relationships with retailers.

Carlos used the data in spreadsheet tables to calculate a net present value and an internal rate of return for the potential investment. The Telesignos Board of Directors required a 20% rate of return for this type of project in Ecuador due to the potential issues with the dollarization of the Ecuadorian economy. In addition, the market for fresh-cut fruit was rather volatile and Carlos wondered if the investment would be wise if the price of their products dropped by 33% or by 50%.

His thoughts were interrupted. It was time for supper and his wife and five children were hungry.