Managerial Autism: Threat–Rigidity and Rigidity's Threat

Abstract

The global financial crisis had a sharply asymmetrical impact on the Australian economy, with a minority of firms growing rapidly during 2005–2010. These gazelle firms experienced internal stress – often positive stress or eustress – parallel to macroeconomic shocks, and these internal stresses were largely independent of external factors. Staw, Sandelands and Dutton's heavily cited threat–rigidity theory (‘Threat rigidity effects in organizational behavior: a multilevel analysis’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, pp. 501–552, 1981) suggests that, when exposed to threat, either internal or external, decision-makers respond conservatively, adhering to previously learned solutions rather than responding innovatively. This study examines five young gazelle firms, established just prior to the economic downturn. It explores management responses to internal and external threats and suggests that rigidity plays a role as an independent variable as well as a consequence of crisis. Drawing on the literature on resilience of individuals in the face of trauma, the study finds that autistic managerial response in approaches to performance management in emerging firms during a crisis is likely to produce additional stress. The paper suggests an organizational model for response to stressors based on Lazarus and Folkman's cognitive appraisal model (Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Berlin: Springer, 1984).

Too cool in a crisis

A re-reading of those 13 dangerous, sleep-deprived days from the context of classic decision-making theory suggests that the cool brinkmanship that commentators admired was, in fact, not the key to a solution to the crisis, but a response to the stress that the decision-makers experienced. Threat–rigidity theory proposes that, in crises such as these, entities such as leadership groups react by reverting to over-learned behaviours, repressing discriminative abilities and reducing sensitivity to stimulation or peripheral cues (Plotnick, Turoff and Van Den Eede, 2009; Staw, Sandelands and Dutton, 1981). Such responses can be adaptive for familiar or ritual threats (Kavanagh, 2008), but crises by their very nature are often rare, unexpected and novel, what Rittel and Webber (1973) call ‘wicked problems’ – such as the Cuban missile crisis. Economic crises, described by Meyer (1982) as ‘transient perturbations whose occurrences are hard to foresee and whose effects on organizations are disruptive and potentially inimical’, share these characteristics and form the background to this study.In reality, Kennedy was both more flexible than the early post-mortems suggested and more sensitive to the Soviet need to salvage something positive from the crisis … The appropriate lesson that should have been drawn from [President Kennedy's] behaviour, then, is that flexibility, compromise, and respect for an adversary's calculus of its vulnerability is essential for the peaceful outcome of a crisis. Instead, the traditional view of what is needed in a crisis – toughness and inflexibility – seemingly has guided U.S. officials for decades, in confrontations from Vietnam to Iraq. (Blight and Brenner, 2007, pp. 28–29)

The threat–rigidity response, that is, the tendency when exposed to externally sourced stress to access only a subset of information or engage in what has been called in the psychological literature premature closure (Keinan, Friedland and Ben-Porath, 1987) has its roots in the work of psychiatrist J. A. Easterbrook in the 1950s (Easterbrook, 1959). Easterbrook's work gave rise to an explanation of the Yerkes Dodson law, which proposes an inverted ‘U’-shaped relationship between threat and cognitive processing, and which came to be known as the Easterbrook hypothesis (Anderson and Revelle, 1982). He suggested that, as arousal increased, the ability to focus on peripheral cues was eroded: threat, in other words, led as much to over-simplicity as rigidity. Prior to this special issue, there were remarkably few articles explicitly touching on performance management systems (PMS) and environmental jolts or shocks, let alone the impact on PMS of internal sources of stress. In relation to threat–rigidity studies specifically linking the phenomenon with PMS, we are not aware of any published papers in the field. However, there is a large and growing literature showing that managers revert to low-risk strategies when organizational performance falls below an aspiration level (e.g. Bromiley, Miller and Rau, 2001; Nickel and Rodriguez, 2002), a crisis not so much in performance as in expectations of performance.

There is a limited spread of papers examining the impact of external stressors, such as the availability of staff, on PMS (Brewer, 2005), and there is an extensive crisis management literature (Smith, 2005) which can be fruitfully applied to the current topic. Euske, Lebas and McNair (1993) do consider the impacts of crises, although the analysis is peripheral to the spine of an otherwise fascinating study. The team examined a handful of large firms in Europe and the USA using a three-phase field, questionnaire and interview approach. They conclude that, when faced with a crisis, ‘organisations abandoned both their formal and informal control mechanisms to exert specific, high intensity forms of control over the “errant” systems’ (p. 275). We suggest that this characteristic of rigidity, a limited ambit of focus combined with a tendency towards a habitual, rote or repetitive response, constitutes managerial autism, by which we infer the primary characteristics of autism, an inward focus, and a tendency to looped responses (Kanner, 1943).

Euske's study hints at a qualitatively different kind of response to that proposed by a simple threat–rigidity hypothesis, and calls into the equation the work by Lazarus and Folkman (1984), who, through their work on coping, have opened up a detailed theoretical and empirical literature, heavily founded on laboratory studies, on the range of responses to stress. Like threat–rigidity theory and Euske's study, however, this body of work has one curious shortcoming. The problem is best understood by posing a question: if threat commonly leads to rigidity, what does rigidity lead to?

Janis and Mann hint at the ‘serious consequences’ and ‘drastic penalties’, but the literature is largely silent on what these consequences and penalties are. This study focuses on the role that rigidity plays in mediating managerial response to a crisis, drawing insights from the psychological literature in suggesting that rigidity is a non-adaptive response to threat, and can lead to a recursive increase in threat or stress.is constantly aware of pressure to take prompt action … He superficially scans the most obvious alternative open to him, and may resort to a crude form of satisficing, hastily choosing the first one that seems to hold promise of escaping the worst danger. In doing so, he may overlook other serious consequences, such as drastic penalties for failing to live up to a prior commitment. (Janis and Mann, 1977, p. 74)

There is no integrated literature or theory on rigidity as a causal variable. Rigidity-like variables can be found in a large range of studies ranging from societal (‘loose–tight’) variability to individual settings (e.g. Oreg et al., 2009). In one of the key early studies on organizational climate, House and Rizzo (1972) developed an organizational scale which gave rise to five dimensions, including formalization, tolerance of error and conflict and inconsistency, rigidity-related constructs that were borne out in empirical work. Similarly, in familial studies, Skinner, Johnson and Snyder (2005) identify autonomy, coercion, chaos and structure as four of their six ‘core dimensions’ (p. 186). What Mellahi and Wilkinson call the ‘curse of success’ literature (2004) suggests that successful firms – and the current study focuses on winners – can become trapped in conservatism in an effort to cope with the competitive pressures associated with rapid growth. Smaller firms such as those investigated in this study, tend to be characterized by informality, even in their routines (Wilkinson, 1999). It is not, however, a ‘curse’ merely of the gazelle – companies which we have defined in this paper as those that have grown to have at least 20 arm's-length employees in the five years since birth. Mellahi, Jackson and Sparks' (2002) exploration of one giant ‘gazelle’ that came to grief, Marks and Spencer (M&S), suggests that one of the core causes of the M&S failure was what they called ‘organizational atrophy’ (p. 26), where internal levers were not pulled sufficiently rapidly in response to external change.

Coping in a crisis

The global financial crisis has been described by former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd as one of the ‘greatest assaults on global economic stability to have occurred in three-quarters of a century’ (Rudd, 2009, p. 20), but ironically, the crisis brought with it bonanza for some Australian companies. Munificence associated with government attempts at stimulus led to a surge in growth in companies positioned to benefit. The impact of the financial crisis on the Australian economy was softened partially – and to a much greater degree than elsewhere in the world economy – through heavy investment in infrastructure-related industries, the continued strength of mining (Gruen, 2010) and $12.7 billion in one-off bonus payments to individuals. The stimulus package not surprisingly had asymmetrical effects on the economy. This paper explores the transit through the crisis of a small subset of companies which not only stayed dry, but thrived, during the storm: start-ups that attained gazelle status during the period 2005–2010, companies benefiting directly or indirectly from an influx of Commonwealth money, but experiencing what Turner, Ledwith and Kelly (2010, p. 745) refer to as the ‘crisis of growth’.

This paper uses the OECD definition of a gazelle firm, that is, one with a staff of at least 20 within five years of establishment. By focusing on small and medium enterprises (SMEs), the paper helps to fill a gap in the PMS literature, which has been dominated by large corporations (Hudson, Smart and Bourne, 2001).

Research exploring the prevalence and practice of PMS in SMEs indicates that performance management is a largely informal process, which does not fit well with typologies of existing PMSs (Hudson, Smart and Bourne, 2001; Tennant and Tanoren, 2005), and SMEs typically have management teams with lower levels of formal qualifications (Fuller-Love, 2006) and fewer formally qualified human resources (HR) staff, making it easier to explore managerial response to crises as a function of the degree to which they are formally equipped to do so.

In this paper, we define PMS, following de Waal (2003), as the formal routines deployed by managers to maintain organizational stasis or progress, with this paper focusing in particular on the personnel aspect of PMSs and the way in which their routines are modified by organizational stress. The literature suggests that managers of SMEs generally orient towards short-term activities, resulting in suboptimal management of staff, information systems and innovation (Tennant and Tanoren, 2005), which suggests that their crisis management capacities will be immature.

A highly evolved literature on response to crises can be found in the work on the psychology of coping, although, from a management perspective, the literature suffers from an overly individual focus. Dominant among the models to emerge from decades of intense research activity in the field is the cognitive appraisal model of response to stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), which, as the name suggests, is more complex and mediated than earlier models of response to stress. Stress, as the title of a paper by one of the pioneers of the field, Hans Selye, put it, was initially considered to be merely ‘a syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents’ (Selye, 1998, p. 230). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) foregrounded the interaction between the ‘nocuous agents’ and the individual's response to that agent. Stress, they posit, occurs when the demands posed by the environment are appraised or perceived to exceed the resources of the respondent. Such perceptions may be false positives, that is, those occasions where individuals believe they are capable of dealing with the crisis, but they are not, or false negatives, where individuals believe they are not capable of dealing with the threat, but they are. Regardless, short of this tipping point, the individual may in fact respond positively to stress (experienced as ‘eustress’, a term introduced earlier by Selye (1998)). Dealing with a threat below this threshold may count as a challenge rather than a stressor. Equally, it is possible to experience threat and challenge simultaneously. There is limited literature linking coping models with managerial response to crises (exceptions include D'Aveni and MacMillan (1990) and Lee and Ashforth (1993)), but the role of flexibility/rigidity in this process is clear: if the assessor is able to modify responses as the nature of the threat changes in time, stress is likely to reduce.

Bonanno (2005; Mancini and Bonanno, 2009) proposes a breakdown of coping styles into two broad categories: pragmatic coping and flexible adaptation, and while he regards both as being potentially adaptive responses to temporary stressors, pragmatic coping is associated with rigid personality characteristics, and the flexible adaptation can become a stable characteristic, enhanced or reduced by developmental experience (Flores, Cicchetti and Rogosch, 2005). Avoidant coping styles are perhaps the ultimate in rigid responses to stressors, capable of freezing response at all stages of the threat response process.

Figure 1 adapts the Lazarus model to managerial coping in a crisis, and draws in the role of rigidity in determining response. It sorts the cognitive appraisal process into key questions, from an initial assessment of the relevance of the crisis through to an assessment of the effectiveness of the response. This appraisal process allows for the possibility that a habitual response, however rigidly applied, may nevertheless be appropriate.

A crisis response model based on the cognitive appraisal model of coping

The model in Figure 1 suggests at least two points where rigidity can arise as a response. First, it may arise at an early stage of assessment, where the manager perceives the crisis cannot be effectively responded to and takes a ‘ride out the storm’ approach. Alternatively, it may arise later in the cycle where, having responded ineffectively, the manager decides not to change tack but, rather, repeats the same response in hope of a better outcome.

The following study focuses particular attention on the role of knowledge of formal performance management processes as a mediator of responses to stress. Specifically, it posits that formal education in such processes – and, more generally, knowledge itself – may set up expectations that can facilitate or impede such responses. Scholars in the management literature generally assume, no doubt intuitively, that ‘learning helps to manage uncertainty’ (Moynihan, 2008, p. 1540), but we suggest that a priori this will only be the case if the learning encourages a flexible approach which allows management to match their response to the crisis. Parker, Storey and van Witteloostuijn (2010) make this point, suggesting that routine application of even ‘best practice’ management strategies is ‘unlikely to foster firm growth in a changing economic environment’ (p. 203). This infers a consonance hypothesis, which presumes that, where organizational structure matches a challenge, performance should be optimized, although such an approach applies to crises somewhat awkwardly. Crises are, by their nature, non-routine and thus intrinsically more difficult to manage (Dynes, 1970). Logic suggests that disjuncture between performance management style and the source of the threat is more likely where managers rely on a set of deeply embedded procedures (Hedberg, Bystrom and Starbuck, 1976), which Hannan and Freeman (1984) suggest will occur in older and larger companies – not the younger and smaller ones examined in the current study. Learning can thus be one of the risk factors in managerial stress, when over-learning leads to a routinized response set in times of crisis. Increasingly, performance management is incorporating reflexive and recursive processes which allow systems to respond flexibly to emerging crises (Bae, 2006). The role of prior experience in generating expectancy and, in turn, the role of expectancy in generating distress are established in the psychological literature (e.g. Harwood, McLean and Durkin, 2007; Janzen et al., 2006; Jarrat, 2008).

This paper takes the exploration of PMS systems in SMEs deeper than the mere presence/absence of a formal PMS system and, recognizing the dearth of such formal systems in SMEs, explores instead the degree of formality of PMS as a causative agent. It examines the response of management strategies of five Australian SME gazelles during the emerging financial crisis during 2005–2010.

The paper explores our earlier question: if threat leads to rigidity, what does rigidity lead to? The model suggests that rigidity in response ultimately gives rise to a new threat: stress. It further attempts to tease out the role that formal PMS systems play in mediating the presence of rigidity in organizational responses.

Methodology

Isolating the participants

By tightly constraining selection requirements, the researchers were able to identify a very small complete population of companies, from which 71% agreed to participate in the study. Subjects were identified by a process of hierarchical elimination (Tversky and Sattath, 1979). The raw data set from which participants were extracted was the 2009 Dun and Bradstreet's Who's Who in Business Australian database. Filters to extract only those participants with at least 20 employees established in the previous five years were applied. The field was then further narrowed down to only those companies based in greater Brisbane, Queensland. The subsequent list of 303 companies was further interrogated to remove companies that had ceased to exist or had been placed under administration, as well as subsidiary companies or joint ventures. This list was cross-referenced with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission in Australia database to ensure that companies established at the same address but under a different name prior to the five-year limit were eliminated from the results, removing false positives from the list. The resulting list of was further reduced by removing amalgamations of professionals (e.g. dentists) and mining companies. The 13 remaining companies were contacted, and a further six companies were eliminated on the basis that they had ceased to trade or violated either the youth or employee count parameter. Of the seven remaining, one declined to participate, one declined to participate immediately, and five agreed to participate immediately in the study. This study focuses on these five firms.

Design

The design of this study is qualitative, using a case-study format (Baxter and Jack, 2008). Interviews and site visits were conducted over a period of four months, with researchers taking a cross-sectional approach to each of the five companies identified in the selection process. Fifty-two formal and informal semi-structured interviews were conducted with staff holding senior, middle and entry-level roles, supplemented with non-participant observation and a documentary review where appropriate. The following analysis focuses, however, on the seven owner-managers of the five companies identified for study. All formal interviews were taped, transcribed and coded in NVivo by categories such as managerial stress, the level of business and formal education, and degree of formality in policy frameworks and adoption. These categories were subsequently ranked by two independent raters.

In addition to taking a company history and gaining an insight into overall company functioning, questioning focused on the employment relations aspects of PMS, and potential sources of innovation/change in the way employment relations were handled. The questions probed the presence of formal policy, the evolution of policy, and the presence or absence of teams, and team-building, formal feedback systems and employee flexibility provisions (both shaped under federal Fair Work Act provisions or developed on an ad hoc basis for the company). The managers were all asked about working hours, stress levels, company financial performance, staff turnover, sense of control and sense of social support interior and exterior to the company, in order to build a picture capable of answering the research question. Direct questioning aimed at uncovering PMS was eschewed in favour of detailed questioning of practice, particularly relating to non-financial goals, enabled PMS systems, both formal and informal, to be revealed in an unobtrusive manner.

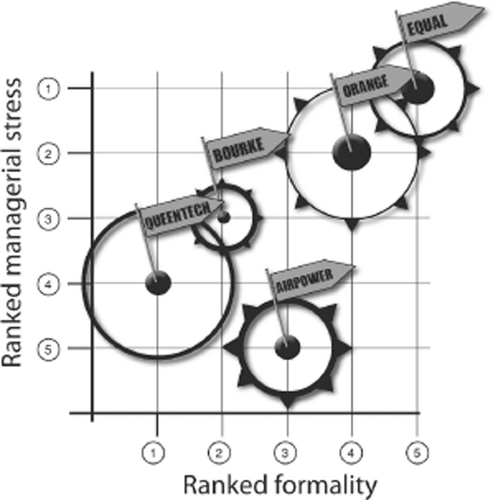

Clustered iconographic charts

Concept mapping was developed at Cornell University by a team headed by Joseph Novak (1990), as a means of physically representing the emerging science knowledge of students, but has since spread to many disciplines, including management (e.g. Kolb and Shepherd, 1997). Concept mapping has its theoretical origins in constructivism, which holds that meaning is recursively constructed by individuals, drawing on their experience (Jonassen, 1991). Concept mapping offers a structured visual representation of variables, very different from the traditional graph or table, created through a more reflective process, and emphasizing complex causation (Kinchin, Hay and Adams, 2000). However, studies have questioned whether concept maps are capable of truly intuitive interpretation (Kolb and Shepherd, 1997). Furthermore, the maps can be difficult to interpret (Turns, Atman and Adams, 2002), and can produce large, unwieldy and idiosyncratic results which are ‘difficult to interpret and impossible to compare’ (Brumby, 1983, p. 9).

This paper is the first in the management literature to deploy a technique of visually assembling and displaying knowledge, clustered iconographic charts (abbreviated as CIX) (Muurlink, 2011; Muurlink and Islam, 2010), introducing four key changes to concept mapping. First, it reintroduces the traditional axes of the graph. By restoring this element of the Cartesian coordinate system, it allows two concepts out of three or more concepts to be emphasized in a familiar two-dimensional representation. Secondly, CIX foregrounds ranked instead of ordinal relationships. By combining ranked and categorical variables (as opposed to any attempt at absolute or scaled values), the method preserves the reflective processes of concept mapping, but allows inter-rater agreement to approach absolute levels in qualitative research, although in using ranking to order data, it needs to be acknowledged that no stringent assumptions about the population other than the ordinal nature of the findings are being supported (Siegel, 1957). Thirdly, unlike traditional concept mapping, CIX makes use of ‘natural signs’ where possible: that is, visual representations that are intuitively related to the concept being represented. Finally, as the name suggests, clustered iconography encourages the simultaneous presentation of a number of variables in a single cluster of icons relating to a single organization. It has become customary to reveal descriptive statistics even in largely qualitative studies, but the CIX approach additionally allows the audience access to greater detail in the data itself. The approach thus complements trends in social science towards an ‘open source’ approach to research (Bodie, 2007; Willinsky, 2005).

Results

Overview of participants: formality of PMS

While the five companies to emerge from the selection process are sectorally diverse, the group also have a number of characteristics in common. For the owner/managers of four of the five firms, this was their first owned-managed enterprise; however, all but one of the managers, the youngest, came from highly paid, senior positions prior to establishing these businesses. The owner managers also had a high degree of variability in the degree to which they were formally educated, in particular in HR. This anticipated variability in both formal and informal HR knowledge provided a good matrix from which to examine the question of response to crisis as a function of knowledge and experience.

- Equal Training's managing director was formally trained in HR at a postgraduate level, and had working experience in a senior HR role. Not surprisingly, only Equal and Airpower's principals explicitly referred to ‘performance management’ as one of their roles. The company was set up with a complement of well-thought-out policies, drawing on the manager's experience as well as professional outside advice, and the formality of the performance management structure was increasing as the company aged. In recent times, the manager had introduced a ‘performance development’ system, which took a holistic view of individual staff performance, and integrated with training opportunities and performance review processes. The manager's attempt to influence the direction of the business was much more detailed:

So we've got five values in the organisation which I live and breathe and I'm trying to get the organisation to live and breathe. So I've taken those five values and built a number of competencies around them that are job specific and from those competencies there will be a number of job specific behaviours.

- Orange Retail has the most extensive formal management structure of the five cases, with a board of directors, a full-time HR manager, an internal company accountant and a health and safety officer. Driving the company's direction, however, is a dynamic young CEO with no formal business experience, but a formal business education. The CEO recognizes the risks and limitations of his age, and has empowered a team of older specialists around him. Owing to the tight margins characteristic of supermarket retail, performance management at the CEO level is, not surprisingly, focused on financial markers (‘the figures always paint the picture’), but owing to consciousness about his age, the CEO did place considerable emphasis on team-building and distributed control.

- Airpower's principals are a former senior power station engineer and an experienced accounting executive. Their company went through a significant incubation period, but while the business had significant formal footings as a result, many of the PMSs became more ad hoc as the company aged. The principals, both tertiary educated, also have actively recruited line managers capable of taking responsibility and managing performance in their teams. As one of the principals put it:

So I guess it comes down to I've got a belief that rules don't make people perform, it's their own motivation and trying to strive towards a common goal, expectations of the company.

- Bourke Civil, the smallest and simplest of the companied identified for the study, was also unique in that it required a high degree of formal education of all its key staff, owing to the nature of the business. The sole principal, like the principals of Airpower, was tertiary trained in a technical field, passionate about the company and highly involved in both the personal and professional lives of his staff. In his own words, it was a ‘pretty chummy sort of outfit, without living in each other's back pockets’. Performance management was focused on economic and quality control issues with a strong client perspective, with the principal, an engineer, developing his own unique project management system with a strong reputation for pulling beleaguered projects back in line. The nature of the company's business was such that it tended to ‘populat[e] a whole bunch of other people's organisational charts’, providing staff on an as-needs basis to complete particular projects.

- Queentech, the one manufacturing firm in our sample, provided the clearest contrast to Equal Training, in that it was formed with a loose business plan by principals with neither extensive HR nor other formal tertiary education, or indeed extensive business management experience. Nevertheless, in the five years since establishment, it had grown to be the largest in our sample, partly driven by the sales acumen of the senior partner and strong quality control in a competitive market sector. Quality was the only sector where management exerted tight control. The company's two principals, however, did show an at times extraordinarily high degree of paternalistic interest in developing staff to their potential.

I'm always just seeing people, analysing what they've doing as I'm walking past and I'll think, okay well, I'm going to put a bit of time into you and see if I can mould you, because they're young, they've got ambition, drive, motivated and they want to learn.

These interventions included helping staff to secure loans from banks.

Stress and formality

My old house, it was owned by the Hargraves families back in 1885, the people behind the Edgells canning factory, and the Hargraves through the depression in the '30s had 400 staff and all their profits went to keeping all these people on, it was like one big family. Then they'd ordered all this tin for all their cans, ex-England, and they couldn't make the £20,000 payment on it and the bank manager at the time stepped in and took over the whole place for that one £20,000 debt … It's a daily reminder to me.

The relationship between formality and managerial stress

With these two exceptions, the ‘weather outside’ was clearly subsidiary to significant internal stressors for the managers of the five case study firms, as they grew from concept to substantial operations in less than five years. Chief among the sources of internal stress were frustrations relating to staff, either the absence of what one manager described as ‘the care factor, the think factor’ – that is, employees passively fulfilling their roles – or the emerging need for policy to cope with staff requests. Witness the case of Equal's manager, who began with a suite of off-the-shelf policies, but found a need to add and adjust policies: for example, private vehicle use reimbursements:And it went one day, ‘She's all over Karl. Sorry …’ And that project was a huge part of our workload at the time … Suddenly we just had job after job, we had half a dozen jobs fall over. And so we had an issue with, well we just didn't have the work, and there was no prospect of other work coming. [We were thinking] … where's our next breakfast coming from?

Turning to the crisis response model presented in Figure 1, we proposed two different points at which rigidity could arise. First, at the early appraisal stage, one might observe a form of studied non-observance (Goffman, 1963) of threats, which arises when the actor (in this case, the manager) recognizes that there is a threat which cannot be effectively accommodated by the firm. A form of ‘sticking to the knitting’ response could be observed in the participants in their negation of the role of the broader financial crisis in their performance management radar. Two of the participants explicitly referred to a deliberate inward focus in their attitude to external crises. As the general manager of Orange Retail pointed out in discussing one of the company's growth-through-acquisition strategies, ‘we can't sit on hindsight; we've got to move forward’. Bourke Civil, which did experience the greatest direct impact of the global financial, resisted the temptation to diversify its operations other than making a deliberate push into an offshore market.Well, I'm trying to [build a business] except for all these people snipping at my heels trying to drag me down with their kilometre reimbursement rates. Oh, Christ [laughing].

Equal's recruitment strategy, for example, used a deliberately ‘high hurdle’ approach, with the manager emphasizing repeatedly a deliberate approach to recruiting excellence. ‘I'm hiring people who match the values of our business’, the manager said. ‘I have very high expectations.’ The manager admitted the approach was not working, and expressed frustration at the lack of autonomous behaviour on the part of even senior staff. The manager's attempts to shape staff behaviour around ‘concrete measurable behaviours’ was, in her own words, failing:We've recently moved towards a … performance development model … where we have a six-monthly and a 12-monthly review and then we go through all of … their performance and what's happening in the marketplace with salaries for this type of job and what's happening with the business and is the business performing well?

According to the manager, the formal PMS had been on the cusp of implementation for six months without success, with staff showing resistance to it, and the manager having insufficient time and energy to ram the system through to implementation.So that's the performance development framework I've tried to develop and then with some people I've put in place these bonuses which then have to be tied to KPI's as well so it's extremely complex. I'm tired just thinking about it. People are so frustrating.

As the model presented in Figure 1 indicates, this manager was caught, to some degree, in a looped response, attempting to impose a method that may not have been adapted to the crisis of growth. As Figure 2 indicates, Equal Training also was relatively financially stressed at the time of the case study work, but this in itself cannot explain the stress experienced by the manager, as the manager also owned a second, highly successful company, and was married to a successful senior professional providing an additional income stream. It is interesting to note that, after the case study was completed, Equal recruited a part-time HR manager.

Conversely, the company with the most flexible response to internal stressors, Queentech, had the least formally educated management team. The two managers described the early phases of growth as highly stressful, but engaged in a non-cyclical response to both external and internal stressors. ‘We're learning by the seat of our pants’, the younger of the two managers admitted. Particularly in terms of HR management, the pair clearly went through a cycle of failure, and reflection, with over 100% turnover of staff in the first year of operation clear evidence of their inexperience at the outset. By the five-year mark, their approach was beginning to pay off.

The two companies without formal business training in their managerial cadre expressed a level of distrust for HR theory at times reaching contemptuousness. For example, Bourke's principal declared: ‘I'm sceptical of expert businessmen who make their living selling books, rather than running a business.’

Similarly, Queentech's general manager had abandoned his one attempt at tertiary business training after just a fortnight: ‘I thought the whole university structure of “you're not allowed to have an opinion, you've got to quote everything from everyone” – that wasn't me.’

For this same manager, however, the early years as noted in the summary earlier, were characterized by frustration, as his untried, intuitive systems came into contact with a messy reality. His ‘training’ in performance management began with a cataclysmic first year, from a staff turnover perspective:I like to mentor and mould [the new apprentices]. If I see a shining light out of the bunch I like to put more time into them. Obviously, my key people, they're always the people that I put time into, but I like to have a select few that are shining through, self-motivated shining through.

Later, his approach modified: ‘You have to be structured, you know, like … I'm trying to set up a bit more of a structure’, ‘Sam’ admitted. ‘Sam's’ unease in adjusting to a more formal role remains, however:In the beginning [turnover] was massive. It was huge, like, 30 in one year, out of a staff of 20. And their attitude, was going out, getting trashed, come to work trashed, not focused, just fucking pissing me off. But I was very, it was zero tolerance. ‘Mate, you're not doing your job. Piss off’, which wasn't the right way to approach it.

Airpower's senior team, with more management experience, adopted a more confident, laissez faire attitude to staff which appeared to be one of the factors underpinning remarkably low managerial stress relative to the other four. As ‘Gordon’, the company's installation and technical-oriented manager put it:I am starting to get the right people. But at the beginning it was just growing that quickly that to try and train people into one of those roles it was just quicker to do it myself. Or just say, mate, can you grab that and put it in that bucket and bring it out here, but really the only way to train someone is for them to understand why they are doing it. But I'm just, it was like, I felt like … it was just like steering a ship and, brrr, it was all: pull jig, it was almost captain like …

His business partner shared this approach to delegating and, as a result, the Airpower workforce had a highly dispersed chain of command: ‘Yeah, and people probably have different styles as well. I've probably delegated to the point of maybe appearing lazy [laughs], I don't know …’It is really quite rewarding to see people employed for one role and then grow into another role [but] … you don't need an army of chiefs … And realistically we've got a lot of tradesmen who are very very happy and comfortable with being tradesmen have got absolutely zero motivation to do any more, and then you have other tradesmen who are young and keen and don't always want to be on the tools and have some ambition and drive …

Whereas companies such as Equal and Orange were highly cognizant of legislative requirements in dealing with performance management challenges and structured their performance management approach accordingly. Airpower, Queentech and Bourke dealt with problems on an ad hoc basis, particularly in relation to staff management. Their innovation arose at least partially from an ignorance of convention combined with their general flexibility in managerial approach.

Parallel to the notion of formality/rigidity in PMS, the study allowed an exploration of innovation in staff management. The lay concept of innovation as the expression of some sort of epiphany on the part of a creative mind or minds (Berkun, 2010) has its place, but in terms of management research, a Schumpeterian view of innovation as merely new to the unit of production, rather than more generally novel (Carland et al., 1984) prevails. The vast product innovation literature preferences the former view, while managerial literature leans toward the latter. It is interesting to note that, of the five companies, Equal demonstrated the highest levels of product innovation: its product had few competitors, none of which had realized the core idea in quite as complete a manner. Apart from Queentech, the other firms showed relatively low levels of product innovation, following well-worn business models. However, Queentech was clearly the most innovative of the five firms in the way it handled staff, and reflected, in a sense, the ignorance of the small, core senior management (who lacked support staff) as to the conventional ways of dealing with performance management issues.

Conclusions

The period 2005–2010 presented two challenges to managers of new gazelles: a destabilized macroeconomic environment, and the challenge of managing rapid growth without the legacy of institutional and cultural knowledge of more established firms. The results confirm that SME PMSs, particularly in relation to our focus on employment relations, are informal (Wilkinson, 1999). Instead, young and relatively small firms such as the five cases explored in this paper, tend to display less structural inertia being ‘little more than extensions of the wills of dominant coalitions or individuals’ (Hannan and Freeman, 1984, p. 158), and thus capable of changing as rapidly as managerial choice dictates.

This study extends previous work on SME PMS, however, by suggesting, in a sequel to stress–rigidity theory, that rigidity itself can be a source of managerial stress, particularly during a crisis. The formality of a PMS is only a single determinant of the ‘rigidity’ or otherwise of a business or managerial response to a crisis, but it forms a particularly interesting pivot in threat–rigidity–stress calculations. It indicates that managers equipped with extensive formal knowledge of business practices, such as performance management concepts, were, if anything, handicapped by their knowledge. The link between formality and rigidity is not necessarily linear. Formal systems enable the efficient processing of information, and can expedite decision-making during a crisis. However, when a ‘wicked’ crisis strikes, one that presents severe and novel challenges, decision-makers – particularly if they lack schemata giving their guidance on how to respond – are forced to extemporise essentially innovative responses. Our findings, then, suggest that ignorance is bliss, not in reducing a sense of responsibility, but in allowing managers a more flexible approach when crises strike.

Thus, this paper posits a possible answer to the central question: if threat leads to rigidity, what does rigidity lead to? It suggests that, just as that threat leads to rigidity, rigidity may lead to three threats to the adaptive functioning of a business: stress, and the autistic characteristics of inward focus and a dysfunctional tendency to repeat responses, regardless of adaptive value. In the most extreme case described in this paper, a company experiencing both the crisis of growth and profitability worries, the principal was the mostly high educated and familiar with formal performance management. The principal's response to the crisis, however, was to some degree formulaic, shaped by training and knowledge rather than by intuition or circumstances.

In this paper, we focused on the role played by education in determining flexibility and drew a link between this relationship and that between education and innovation, which involves relatively novel responses to business challenges. Early studies of this latter connection were predicated on a more-the-merrier view: for example, that innovation in agribusiness was linked to the educational level of farm managers (Nelson and Phelps, 1966). Our study suggests a potential paradox in relation to the dangers of formal education in shaping managerial expectations. It is not the first to do so. Baumol (2004) is a particularly trenchant critic of conventional education as a source of innovation in general, arguing plausibly that true innovation may require responses untrammelled by conventionally structured knowledge. Others have focused on disciplinary differences and their impact on flexibility. Wiersema and Bantel (1992) assayed the top management teams at 87 large manufacturing firms, examining education level as well as discipline. With regard to discipline, they grouped science and engineering training together as being theoretically orientated to greater acceptance of change as opposed to an education in business or the humanities. ‘Science and engineering’, they controversially posit, ‘are concerned with progress, invention, and improvement.’ They found evidence to support their hypothesis that those with an engineering or science education were more open to strategic change. This study supports that finding, but suggests a framework to reinterpret the relationship. The key variable is the degree to which education hardens the cognitive set toward new problems or, alternatively, the ability to generate novel responses. Education can lead to over-learning and the generation of stereotypical responses that are relatively resistant to change (e.g. Devine, 1989), and needs to recognize that business managers operate ‘with messy, incomplete, and incoherent data – [where] statistical and methodological wizardry can blind rather than illuminate’ (Bennis and O'Toole, 2005, p. 3).

It is interesting to speculate that, unless experience happens to provide heterogeneous challenges, it may only increase the formality of response to future crises. Such a suggestion complements relatively new research on the value of failure as a learning tool in business (McGrath, 1999; Minniti and Bygrave, 2001). A lack of familiarity with failure may lead to an avoidant attitude towards future challenges with failure potential, leading to what we suggest can be described as managerial autism in response to crises. This tendency towards looped, inward-looking responses to challenges may not only ultimately cause stress, as this study suggests, but could also potentially lead to business failure.

Biographies

Dr Olav Muurlink is a psychologist working as a Research Fellow, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University.

Professor Adrian Wilkinson is Director of the Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing. He holds Visiting Professorships at Loughborough University, Sheffield University and the University of Durham.

Professor David Peetz is Professor of Employment Relations at Griffith University.

Dr Keith Townsend is Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing.