Investigating low rates of compliance to graduated compression therapy for chronic venous insufficiency: A systematic review

Abstract

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is a chronic lower limb progressive disorder with significant burden. Graduated compression therapy is the gold-standard treatment, but its underutilisation, as indicated in recent literature, may be contributing to the growing burden of CVI. The aim of this systematic review is to determine the reasons for poor compliance in patients who are prescribed graduated compression therapy in the management of chronic venous insufficiency. A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify the reasons for non-compliance in wearing graduated compression therapy in the management of chronic venous insufficiency. The keyword search was conducted through Medline, PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane library, AMED, and Embase databases from 2000 to April 2023. Qualitative and quantitative studies were included with no study design or language limits imposed on the search. The study populations were restricted to adults aged over 18 years, diagnosed with chronic venous insufficiency. Of the 856 studies found, 80 full-text articles were reviewed, with 14 being eligible for the review. Due to the variability in study designs, the results were summarised rather than subjected to meta-analysis. There are five main overarching themes for non-compliance, which are physical limitations, health literacy, discomfort, financial issues, and psychosocial issues with emerging sub-themes. Graduated compression therapy has the potential to reduce the burden of chronic venous insufficiency if patients are more compliant with their prescription.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is a common lower limb disorder that presents significant burden in terms of morbidity, healthcare costs, and decreased quality of life.1 The progressive stages of CVI are classified by the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, and Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification system (Table 1). The disorder is a significant problem in Australia with a prevalence of 25%–40% in women and 10%–20% in men, and annual incidence rates of 2%–6% and 1.9% in women and men, respectively.2 The most serious complication of CVI are venous leg ulcers (VLUs),3 which are responsible for 70% of all lower limb chronic ulcers,1, 4-6 and have a prevalence of 3.3/1000 in people over the age of 60 years.7 Current data suggests that the prevalence and burden of CVI will continue to grow due to the increase in the older and obese populations, who are most at risk of developing CVI.8, 9 Currently, 67% of Australians are overweight or obese, and It is estimated that more than 18 million Australians will be overweight or obese by 2030.10 As of June 2020, 16% of the Australian population was aged 65 years or over, and figures suggest that by 2066 this will increase beyond 23%.11

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| C0 | No visible/palpable signs of venous disease |

| C1 | Telangiectasias or reticular veins |

| C2 | Varicose veins |

| C3 | Oedema |

| C4 | Skin changes secondary to chronic venous disease (haemosiderin, lipodermatosclerosis, atrophie blanche) |

| C5 | Healed ulcer |

| C6 | Recurrent active venous ulcer |

VLUs, the final stage of CVI, are estimated to cost the Australian healthcare system $400-500 AUD million per year,12 and Australian patients $27.5AUD million.13 In 2016, varicose veins (VVs) alone were estimated to cost over $400 AUD million globally, a figure expected to surpass $600 AUD million in the coming years.14 Importantly, all stages of CVI have a significant impact on a person's quality of life.15 Pain is the main limitation described by people who have progressed to a VLU, with 45% of people becoming housebound,16 50% suffering with daily activities, and 25% suffering with anxiety or depression.3

In Australia, a patient who presents to their general practitioner (GP) with early signs of the disease is referred for further vascular assessment involving duplex ultrasound and vascular specialist consultation.17, 18 This will identify the cause of swelling/varicosities, to grade the severity of the venous valvular incompetency, and to assess lower limb arterial blood supply.17 Depending on the severity of CVI, a patient is then offered a series of interventions to treat the disorder and prevent its progression. The most conservative of these is the ‘gold-standard’, which includes the use of graduated compression therapy (GCT), and the adoption or maintenance of a healthy lifestyle including smoking cessation, a balanced diet, and exercise. GCT has been shown to be less invasive, readily available, and more cost-effective19 compared to other treatment options, which include the use of medications, thermal and laser ablation, sclerotherapy, and venous ligation.20

Although GCT is considered the mainstay treatment, like all treatments, it is not without limitations. Consequently, patients do not always adhere to health recommendations.21 Recent literature suggests that there is an underutilisation of GCT.19, 22 VLUs, therefore, remain an ongoing challenge, with 60–80% recurring within three months.1, 5, 23 The skin is the most vulnerable three months after healing and it has been shown that for every additional day of wearing GCT the chance of recurrence halves.24

The aim of this systematic review is to understand the reasons of non-compliance to GCT as a treatment and prophylactic modality in CVI. Understanding the barriers to wearing GCT may guide future research to improve the management of CVI and decrease the burden associated with the disease. In Australia, patient compliance in wearing GCT to prevent the progression of CVI, and to prevent recurrence of a VLU, has the potential to save the government $1.4AUD billion annually.13

2 METHODS

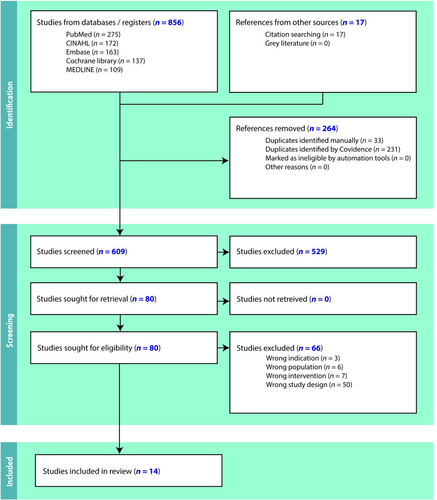

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify the reasons for non-compliance in wearing GCT in the management of CVI. The protocol was registered on the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (ref: CRD42023413592) prior to commencement of database searches. This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.25

One reviewer (ES) independently extracted relevant data from included full-text articles. Quality appraisal of the research was undertaken independently by two authors (ES and MB) (Appendix 1). The appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS) was used for critical appraisal, which has been shown to have high validity and reliability.26, 27

2.1 Search strategy

The search strategy was developed via Medline and adapted to the syntax of the other databases searched (Appendix 2). All searches were conducted through Medline, PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane library, AMED, and Embase databases from 2000 to April 2023. Further studies were retrieved from backward manual searches of references listed in included studies. Additionally, PROSPERO was searched for any relevant, ongoing, or completed reviews of a similar nature.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included with no study design or language limits imposed on the search. The study was limited to publications from the year 2000 onwards that included adults aged over 18 years with a diagnosis of CVI. Studies focusing on practitioner compliance and prescription rates, compression bandages only, other leg ulcers (e.g., diabetic or arterial) were not included.

2.3 Study selection

Following the database searches, initial literature results were uploaded to Covidence28 to facilitate collaboration among reviewers. The title and abstract screening were performed independently by two authors (ES and MB), any conflicts were resolved via discussion between the two reviewers. Upon agreement of the initial screen, full-text extraction was conducted by two authors independently (ES and MB) against the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed above. Any discrepancies were resolved either by discussion between the two reviewers or by a third author (AC) until consensus was reached.

3 RESULTS

Of a total of 873 articles that were identified through the database searches, 80 articles were deemed eligible for full-text screening. From this, 66 full texts were excluded, leaving a total of 14 studies eligible for inclusion (Figure 1).

3.1 Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 14 studies included: primary author of the study, publication year, country, sample size, study design, and study aim (Table 2). Included are nine quantitative studies and five qualitative studies that were published between 2005 and 2023.

| Authors name and country | Sample size | Study design | Study aims |

|---|---|---|---|

Ayala et al. (2019)29 Colombia |

1414 | Prospective cohort | To describe compliance rates of compression therapy in a cohort of patients with chronic venous disease and also to describe frequent causes of non-compliance. |

Cataldo et al. (2012)30 Brazil |

3414 | Prospective, descriptive, cross-sectional, multi-centre study | To analyse the medical indication and the use of elastic compression stockings, and to assess patient adherence to treatment in different regions of Brazil. |

Coral et al. (2021)42 Brazil |

240 | Cross-sectional observational study | To analyse the rate of adherence to wearing graduated compression stockings and to understand the problem of treatment non-adherence. |

Dereure et al. (2005)39 France |

2842 | Prospective observational study | To evaluate concordance with compression therapy in ambulatory patients with venous leg ulcers. |

Dialsingh et al. (2022)31 Caribbean |

193 | Prospective, observational study | To determine the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with Chronic Venous Disease (CVD) across the Caribbean, and to evaluate patients' compliance to conservative therapy and the effectiveness of such therapy in reducing patients' CVD symptoms. |

Gong et al. (2020)40 China |

10 | Descriptive qualitative study—semi-structured, in-depth, face-to-face interviews | To explore the comprehensive reasons for patients' non-compliance with graded elastic compression stockings (GECS) as the treatment for lower limb varicose veins. |

Perry et al. (2023)38 UK |

25 | Interpretive, qualitative, descriptive study | To explore barriers to, and facilitators of, adherence to compression therapy, from the perspective of people with venous leg ulcers. |

Raju et al. (2007)32 USA |

3144 | Retrospective, qualitative face-to-face interviews | To understand the use, compliance, and efficacy of compression stockings. |

Rastel (2014)41 France |

140 | Observational study | To study patient compliance towards compression stockings |

Shannon et al. (2013)37 USA |

71 | Cross-sectional study | To describe patients' adherence to clinical recommendations for preventing recurrent venous leg ulcers (VLUs). |

Soya et al. (2017)33 Africa |

200 | Retrospective cross-sectional study | To determine factors in compliance with wearing elastic compression stockings. |

Stansal et al. (2013)36 France |

100 | Prospective observational cohort study | To evaluate compression therapy for venous leg ulcers in terms of adherence, acceptability, quality, and effectiveness. |

Torres-Martinez et al. (2015)34 Mexico |

150 | Observational, descriptive, cross-sectional cohort correlation study | To describe how adherence to the use of compression stockings modifies the perception of quality of life in health in patients with chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). |

Ziaja et al. (2011)35 Poland |

16 770 | Cross- sectional survey | To evaluate non-compliance with compression stockings in chronic venous disorder (CVD) patients. |

3.2 Study outcomes

The outcomes of the studies included: prescribing practitioner, type of compression therapy, compression class, compliance rates, and main reasons for non-compliance (Table 3). Of the included studies, 57% focused on the various stages of CVI,29-35 29% focused on VLUs,36-39 and 14% focused on VVs.40, 41 Compression class was only stated in 36% of the studies29, 31, 33, 36, 41 and type of compression garment used was only stated in 79% of the studies.29-33, 36-41 In 64% of the included studies, female was the predominant sex that participated.5, 29-32, 34, 36, 41, 42 One study did not record the sex.39

| Author and study type | Prescribing practitioner | Condition | Type of compression therapy | Compression class | Compliance rates | Main reasons for non-compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ayala et al. (2019)29 Prospective cohort study |

Vascular specialist | CVI | Stockings (95.6%)

Bandages (4.4%)

|

Light = <8 mm Hg (6.2%) Mild = 8–15 mm Hg (55%) Moderate = 15–20 mm Hg (36.2%) Strong = 20–30 mm Hg (2%) Very strong = 30–40 mm Hg (0.6%) |

Compliant (31.8%) Mostly compliant (31.4%) Sometimes compliant (28.3%) Never compliant (8.5%) |

|

Cataldo et al. (2012)30 Prospective, descriptive, cross-sectional, multi-centre study |

Not stated | CVI | Stockings

|

Not stated | Compliant (66.8%) |

|

Coral et al. (2021)43 Cross-sectional observational study |

Not stated | CVI | Not stated | Not stated | Compliant (55.8%) |

|

Dereure et al. (2005)39 Prospective observational study |

General practitioner | VLUs | Stockings (43.9%) Bandages (52.6%) Intermittent pneumatic compression (3.5%) |

Not stated | Compliant (78.5%) Mostly compliant (18.7%) Never compliant (2.8%) |

|

Dialsingh et al. (2022)31 Prospective observational study |

Vascular specialist | CVI |

Stockings (17.6%)

Bandages (8.9%)

|

Light (3.6%) Mild (18.7%) Moderate (11.4%) Strong (2.1%)* mm Hg not mentioned |

Compliant (76.2%) |

|

Gong et al. (2020)40 Descriptive qualitative study |

Not stated | VVs | Stockings | Not stated | Never compliant (100%) |

|

Perry et al. (2023)38 Interpretive, qualitative, descriptive study |

Not stated | VLUs | Stockings alone (8%) Bandages (68%)

Bandages and stockings (8%) Inelastic compression wraps (12%) Other (4%) |

Not stated | Compliant (84%) Sometimes compliant (12%) Never compliant (4%) |

|

Raju et al. (2007)32 Retrospective qualitative face-to-face interviews |

General practice or vascular specialist | CVI | Stockings | Not stated | Compliant (21%) Compliant most days (12%) Sometimes compliant (4%) Never compliant (63%) |

|

Rastel (2014)41 Observational study |

Not stated | VVs | Stockings (percentages unclear)

|

CCL1 (6.7%) CCL2 (83.1%) CCL3 (3.4%) Unknown (6.7%) |

Compliant (29.2%) Never compliant (70.8%) |

|

Shannon et al. (2013)37 Cross-sectional study |

Not stated | VLUs | Stockings | Not stated | Compliant (73%) Sometimes compliant (18%) Missing data (9%) |

|

Soya et al. (2017)33 Retrospective, cross-sectional study |

Not stated | CVI | Stockings

|

CCL2 (36.6%) CCL3 (63%) CCL4 (0%) |

Compliant:

|

|

Stansal et al. (2013)36 Prospective, observational, cohort study |

General practitioner (n = 15) vascular specialist (n = 85) | VLUs | Stocking (25.8%) Bandages (74.2%)

|

CCL1 (3.3%) CCL2 (13.5%) CCL3 (9%) |

Compliant (89%) |

|

Torres-Martinez et al. (2015)34 Observational, descriptive, cross-sectional, cohort, correlation study |

Not stated | CVI | Not stated | Not stated | Compliant (21.3%) Sometimes compliant (12%) Never compliant (66.6%) |

|

Ziaja et al. (2011)35 Cross-sectional survey |

General practitioner or vascular specialist | CVI | Not stated | Not stated | Compliant (25.6%) |

|

The literature search revealed diverse reasons for non-compliance, with significant overlap between the studies. For this reason, the thematical interpretation of the results has been categorised into the five main overarching reasons for non-compliance, with emerging sub-themes. The main reasons for non-compliance to GCT are physical limitations, health literacy, discomfort, financial issues, and psychosocial issues.

4 DISCUSSION

Compliance rates varied considerably between included studies. Soya et al. (2017) followed 200 subjects over a 22-month period and found that compliance rates were initially 58.5%, but this significantly decreased throughout the study to 11%.33 Compliance rates were generally highest in the studies where participants were prescribed GCT and were reviewed at a follow-up appointment between one week and three months after prescription.29-31, 39 There was a correlation found between disease severity and likelihood of compliancy, where with VLUs participants were more compliant than participants with earlier stages of CVI.35-39, 43 Another study that only interviewed participants who were always non-compliant found that many participants did not know VVs were a condition with serious complications.40 Adherence was also found to be better when participants were being managed by a vascular specialist compared to a nurse or GP.36

The main reasons found for non-compliance are physical limitations, health literacy, discomfort, financial issues, and psychosocial issues. Similarly, Bainbridge et al. (2013) and Chitambira et al. (2019) found comparable reasons for non-compliance when they reviewed GCT in the treatment and prevention of VLUs.21, 44

4.1 Physical limitations

Each study in this review noted that physical limitations, leading to difficulty in garment application and removal, influenced compliancy. The application of a compression stocking requires a person to have the flexibility, coordination, strength, and dexterity to correctly and safely pull a garment on and off, and both age and obesity make this task extremely difficult, or impossible.45

This analysis found that patients not only have application/removal difficulties, they also often require assistance, cannot reach their feet, have weak and painful hands, or they find it difficult to put footwear on with the garments in place.32, 36-38, 41

Interestingly, none of the included studies mentioned an association between difficulty in application and age or body mass index (BMI). Six of the 14 studies noted that difficulty of garment application was one of the main reasons for non-compliance.29-31, 36, 37, 39 Interestingly, most of these studies involved patients with active ulcers, suggesting that difficulty in application may be related to the pain associated with a VLU and/or the requirement to apply a garment over a primary wound dressing.

4.2 Health literacy

Understanding the benefit of GCT and the progressive nature of CVI will influence compliance with prescription. Of the included studies, 10 mentioned lack of health literacy as a contributing factor to non-compliance.29, 32, 34-36, 38-41, 46 This included, but was not limited to, poor understanding as to why they need to wear GCT, a feeling the therapy is ineffective or unnecessary, a belief that CVI is not a serious disease, and a lack of understanding of the benefits of the therapy in general.

Health literacy is also a concern from the healthcare provider (HCP) perspective with some not prescribing GCT when indicated, and others failing to adequately explain the benefits and requirements of the prescription.32, 34-36, 38-40 One study found that there was a reduced prescription rate among GPs when GCT was warranted.35 Participants in Dereure et al. (2005)'s study on compliance in patients with VLUs indicated that they felt GCT may in fact worsen their ulcer, perhaps indicating problems in the delivery of GCT education.39 Both Gong et al. (2020) and Raju et al. (2007) included participants who were never recommended GCT by their HCP.32, 40

Harker et al. (2000) found that patients want to understand as much information about their condition as possible, however, felt they were given inadequate information at times by their HCP, which can result in low compliance towards treatment.47 Regarding the ineffectiveness of the therapy, it cannot be concluded if participants followed the HCP's instructions and adhered to the recommended time for an effect to occur or the benefits and timeframe were not thoroughly discussed by the HCP.

4.3 Discomfort

A variety of subjective terms were used by participants to describe reasons for non-compliance, which we have collectively classified as ‘discomfort’ for the purposes of this review. Discomfort included such terms as itchiness, heat, pain, worsening symptoms, skin issues, tightness, and incorrect fit. Poorly fitted GCT not only reduces the adequacy of compression to treat the disorder, possibly potentiating the CVI symptoms, it can lead to tightness, pain, and even tissue necrosis.48 For this reason, it is important for a patient to have correct measurements taken of their limb to ensure the therapeutic and comfortable fit of a garment from a manufacturer with a wide range of sizes.

Despite the worsening of symptoms of CVI during hotter weather, there was no association found between climate and discomfort due to heat as a reason for non-compliance. For example, a Caribbean study found that sweating was only a minor reason (9.1%) for non-compliance.31 In the same instance in a Abidjan (West Africa) study heat was not a reason, however, the work environment was selected by 8.7% of participants and it was found that the participants who were less compliant due to work environment were working at multiple sites.33 This may mean that being outdoors was more likely to contribute to over-heating from the garments and this may, in turn, lead to poorer compliance. Interestingly, studies conducted in France and Poland, where the climate is cooler compared to tropical regions, had heat, or sweating as one of the main reasons for non-compliance.35, 39, 41 Another way to interpret these results is that people in colder climates may have a lower heat tolerance compared to people living in warmer climates, and perhaps influencing compliance in different ways in different geographical regions.

4.4 Financial issues

The treatment and prevention of progression of CVI is continuous due to the chronic nature of the disorder. Once diagnosed, it is recommended that patients wear GCT long-term to prevent progression of the condition.49 GCT needs to be replaced every 3–6 months due to the loss of elasticity (and therapeutic effect) of the garments due to normal wear and tear.50 The retail price of GCT is variable across medical compression companies, particularly depending on the style, compression class, material, and size range of compression.

Participants in several studies documented that cost-to-purchase was one of the reasons they did not comply with their prescription.30, 32, 34-37, 40, 46 The two studies that indicated cost-to-purchase as one of the lowest contributing factors were both American studies.32, 37 Armstrong et al. (2017) reported that in the USA insurance companies often cover the costs of GCT, while in other international countries, the patient, regardless of health cover must cover the cost.51 In Australia, private health funds will cover up to 2–4 pairs per year.52 One Polish study of 16 770 participants indicated that 33% of the study population did not wear GCT due to the cost-to-purchase which was the main outcome of the study.35 The thematic analysis of cost- to-purchase is likely to be skewed by the sociodemographic area that the research was conducted in.

4.5 Psychosocial issues

The psychosocial issues impacting compliance that were identified in the studies included a lack of self-discipline to wear the garments and their perceived unappealing nature. Five studies noted a lack of self-discipline as a reason for non-compliance.30, 32, 33, 37, 46 Patients simply did not want to wear them, could not be bothered to put them on, or did not prioritise the time for application.

Among the studies who found the garments to be aesthetically unappealing, female was the predominant sex within the participant population.29-32, 34, 42 This indicates a potential association between the female gender and unwillingness to wear GCT, since they are more likely to want to wear clothing that exposes the legs and feet, compared to the male population.

5 LIMITATIONS

This review was limited by the fact that many of the studies included in the analysis failed to directly specify the type and class of compression used, or who prescribed and managed the therapy. Furthermore, when the articles did specify the above information, there was considerable variation between the authors in the clinical terminology used for the type of compression (i.e., elasticated stockings vs. inelastic wraps, vs. multi-layer compression bandages), the class of compression (i.e., ‘light’, mild’, ‘strong’ vs. the standardised CCL1, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4), and the therapy prescriber (i.e., GP, vs. vascular specialist, vs. nurse). As a result of these deficits and inconsistencies, it was difficult to make associations between precise indications for GCT, their specific treatment modalities, and the participant's reasons for non-compliance.

Another limitation was the variation between study designs, with some studies employing a quantitative approach compared to a qualitative one. As such, the nature of questions asked to participants varied greatly between the studies, with only some overlap. This complicated efforts to precisely compare patient reasons, leading to a more generalised, thematic interpretation.

6 CONCLUSION

This systematic review has highlighted a range of reasons for non-compliance with GCT prescription. The participant justifications are complex and diverse with substantial overlap between the included studies. Early diagnosis, treatments, and management plans to prevent the progression or recurrence have the potential to significantly reduce the substantial healthcare costs and improve patients' quality of life.

At present, limited data is available regarding compliance rates and reasons for compliance or non-compliance in Australia, despite a rise in the prevalence and incidence of CVI. Further research is required locally to comprehensively understand patient attitudes towards their prescription and the barriers to compliance in the Australian context to improve the management of CVI and reduce its growing burden.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Newcastle, as part of the Wiley - The University of Newcastle agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [Elise Stevenson] at http://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.14833.