Exploring the Stepped Care Model in Delivering Primary Mental Health Services—A Scoping Review

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

The stepped care model (SCM) is a patient-centred approach to mental health care, offering a range of services from least to most intensive, tailored to individual needs. This scoping review examines the adoption, effectiveness, challenges and implications associated with applying SCM within primary mental health service delivery. Evidence from global sources suggests the model is viable, effective and useful. This review explores the literature available, clarifies fundamental concepts and identifies existing knowledge gaps. The literature search included CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus, the Federation University library, Google and Google Scholar databases. A systematic keyword-based search using terms like “stepped care model,” “mental health,” and “primary care”; and a combination of keywords and subject headings, were used. The search strategy was refined by considering factors such as relevance, publication date, objectives and outcomes. This strategy yielded 20 papers compiled in this review. They include randomised controlled trials and cross-sectional studies. The review supports SCM adoption in primary mental health care but acknowledges the need for further research. Key inclusions of the review include cost-effectiveness, diverse diagnoses, efficacy and the model's structural configuration. Clear treatment details, delivery methods, intervention durations and chronological sequences are essential. This systematic approach enhances generalisability across different SCM models and areas, strengthening reliable inferences. In summary, the SCM holds promise for enhancing mental health service delivery. However, there is a need to further examine the factors that determine its effectiveness and understand the different ways in which SCM is implemented. Such inquiry forms the foundation for implementing and advancing mental health care services in Australia and internationally.

1 Introduction

Mental health challenges are a global concern and equally prevalent in Australia. Worldwide, 1 billion people experience mental health disorders, with depression and anxiety accounting for over 50% of these cases (World Health Organization [WHO] 2022). In Australia, 22% of individuals aged 16 and over, and 14% of those aged 4–17 have experienced mental illness over the past year (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2024b). For Australians, mental illness is the second-largest contributor to years lived in ill health and ranks fourth in reducing total years of healthy life, following cancer, cardiovascular diseases and musculoskeletal disorders (AIHW 2024b).

Since the transition from large psychiatric asylum hospitals to community-based care began in the mid-1950s, significant changes have occurred in mental healthcare delivery. This deinstitutionalisation process involved closing isolated psychiatric institutions and relocating facilities to main hospital sites, where integration with mainstream health services became the norm (Calabria and Cullen 2024). Diverging from lifelong institutional care models, community-based care now plays a significant role in delivering mental health services. Extended inpatient admissions are diminishing with limited and brief admissions being standard practice (Gooding 2016).

In current healthcare systems, services are generally delivered across primary, secondary and tertiary care settings. In Australia, primary health care is generally the initial point of contact for people seeking healthcare interventions (AIHW 2024a). These services do not operate in isolation and are interconnected with the broader healthcare system (AIHW 2024a). Primary mental health care delivers multiple interventions from early to complex stages, often resulting in referrals of patients to other areas (Isaacs and Mitchell 2024). Its services include mental health promotion and prevention, early identification and diagnosis of mental health disorders, treatment of highly prevalent disorders, management of complex yet stable disorders and referrals to other mental health services if required (Isaacs and Mitchell 2024). Across Australia, health professionals delivering mental health services include GPs, psychiatrists, mental health nurses, social workers, occupational therapists and Aboriginal health workers (Department of Health [DoH] 2019).

The Stepped Care Model (SCM) is a staged model of care designed to deliver patient-centred care through a graduated suite of services, ranging from the least to the most intensive based on individual needs (DoH 2019). The SCM in primary mental health aims to provide tailored, optimal and dynamic patient-centred care. As the needs of patients evolve, SCM services should be continuously adapted and enhanced, made possible through a skilled workforce and cutting-edge care delivery methods, including the use of modern technology (DoH 2019).

The SCM emerged in 2006 as part of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health [NCCMH] 2023). This initiative aimed to provide structured services that were easily accessible and evidence-based. It is also aligned with contemporary clinical policies for the treatment of high-prevalence disorders (NCCMH 2023). According to the source, the IAPT initiative and specifically the IAPT programme, formed part of UK government-funded reforms established to respond to the challenges of mental health services postdeinstitutionalisation. These challenges included disintegration of care, poor coordination, inadequate funding, population growth and an increasing demand for services (National Health Service [NHS] 2017; Gandré et al. 2019). Key principles of the programme included evidence-based approaches and ensuring an adequately skilled workforce with services based on the SCM (NCCMH 2023).

Since its inception, the SCM has gained acceptance and has been endorsed and implemented in countries such as France, Germany, Holland, the United States of America, Canada and New Zealand (Franx et al. 2012; Gandré et al. 2019; Maehder et al. 2021; NHS 2017).

Numerous international studies have scrutinised primary mental health services, delving into and analysing the SCM, its efficacy and the ramifications for individuals accessing this model of care delivery (Anderson et al. 2020; Chatterton et al. 2019; Delgadillo, Gellatly, and Stephenson-Bellwood 2015). Within this body of research, investigations have discerned that there are benefits to SCM service delivery. Additionally, studies have contended that the SCM manifests economic viability, thereby constituting a financially pragmatic approach with both patients and clinicians reporting positive experiences with the model (Collins et al. 2020; Muntingh et al. 2014; Salomonsson et al. 2018).

1.1 Aim

This review aims to explore the existing literature on the SCM. The review uncovers the modes of SCM delivery and the experiences of patients and healthcare professionals. In addition, this review identifies the knowledge gaps within Australia's primary mental health context.

The following primary question guided the review:

What is known from the existing literature about the SCM in delivering primary mental health services?

- What are the different modes of delivery within the SCM?

- What factors are pertinent to the effectiveness of the SCM delivery?

- Is the SCM an economically viable model of primary mental health care delivery?

- What are the reported stakeholder experiences involved with the SCM?

2 Methods

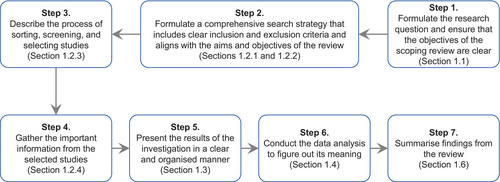

The study explored the breadth of the SCM through a scoping review. Scoping reviews are suitable when considering the available evidence identified from an initial search. A scoping review helps to identify and address gaps in knowledge, by facilitating the identification and analysis of key concepts derived from existing evidence (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). This review adhered to the methodology initially developed by Arksey and O'Malley (2005) and, later improved by Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien (2010) and the Johanna Briggs Institute (JBI) institute (Pollock et al. 2021). The review followed seven stages, including the methodology for conducting the literature search, reviewing evidence and synthesising findings as explained by Pollock et al. (2021). Figure 1 below outlines this process.

2.1 Inclusion Criteria

The main objective of the review was to systematically gather and evaluate articles on SCM primary mental health services, to contribute to a thorough comprehension of the approach to service delivery. The review established initial inclusion criteria to systematically identify relevant articles. The criteria, however, were refined during and after the searches as the understanding of the current literature evolved. To be included, evidence sources had to (a) focus on mental health care services specifically delivered through the SCM and (b) be set within the realm of primary mental health care.

2.2 Literature Search Strategy

The literature search included the following databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Scopus. An additional search was conducted on Google Scholar, and the Federation University's Library which encompasses all book and e-book titles, University library collections, most journal articles and the institution's research repository. A Google search of literature was also conducted, which focused on government reports, Primary Health Network reports and other organisations involved in delivering SCM services.

A systematic search was conducted, and Table 1 below 1 presents the search terms used in each database and the combinations of search concepts. A review of the bibliographies of articles included in the review was also conducted.

|

1. CINAHL search (stepped N6 (care OR healthcare) OR “stratified step*” OR “progressive stepped”) AND (MH “Primary Health Care” OR “primary care” OR “primary healthcare” OR “primary health care” OR “community care”) |

|

2. MEDLINE search (stepped N6 (care OR healthcare) OR “stratified step*” OR “progressive stepped”) AND (MH “Primary Health Care” OR “primary care” OR “primary healthcare” OR “primary health care” OR “community care”) |

|

3. PsycINFO search (stepped N6 (care OR healthcare) OR “stratified step*” OR “progressive stepped”) AND (DE “Primary Health Care” OR DE “Integrated Services” OR DE “Community Psychiatry” OR “primary care” OR “primary healthcare” OR “primary health care” OR “community care”) |

|

4. Scopus search (stepped W/6 (care OR healthcare) OR “stratified step*” OR “progressive stepped”) AND (“primary care” OR “primary healthcare” OR “primary health care” OR “community care”) |

2.3 Articles Screening and Selection

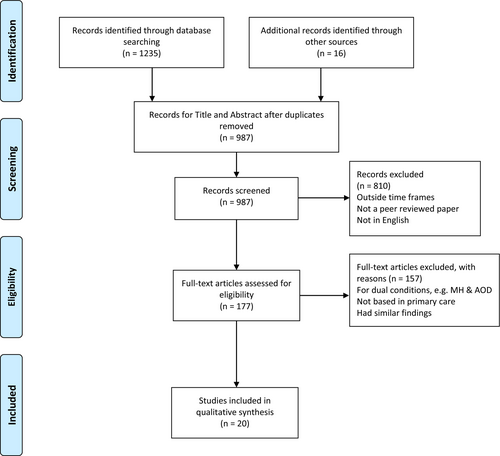

The search strategy (outlined in Section 2.2) produced 1251 papers. Duplicates were removed, and additional screening was conducted. The title and abstract were reviewed, and full-text articles that met the following criteria were included: (a) papers published between 2012 and 2024, (b) peer reviewed papers, (c) papers written in English and (d) studies focusing on the SCM and outcomes of interest. This screening resulted in 177 papers.

The first author conducted additional eligibility assessments. This included reviewing the papers and excluding (a) studies that looked at mental health together with another condition, (b) studies not based in primary care, and (c) studies that focused on mental health conditions and had similar findings. The last author undertook an independent review of decisions for inclusion and exclusion. This resulted in the exclusion of a further 157 papers. Following the described process, a total of 20 papers were included in this literature review. Figure 2 below, the PRISMA diagram, summarises the search process, which aligns with the JBI scoping review methodology, that was followed to arrive at the papers included in Section 3.

2.4 Data Extraction Procedure

During data collection, the following information was captured for every entry: authors and country; aim; demographics, diagnosis, sample size; methodology; measures; and major result. The literature data charting Table 2 on pp. 8–13 summarises this information across all 20 sources that were included in the scoping review.

| Authors and country | Aim | Demographics, diagnosis, sample size | Methodology | Measures | Major result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (2020), Australia | To explore SCM's acceptance among GPs, GP staff and patients |

|

Codesign and feasibility study |

|

|

| Apil et al. (2014), the Netherlands | To determine the feasibility and effectiveness of a Stepped Care Program in preventing relapse of depression in participants 55+ |

|

RCT |

|

|

| Boyd, Baker, and Reilly (2019), England | To explore the impact of progressive SCM compared to stratified SCM in improving access to psychological intervention services |

|

Observational cohort study analysing retrospective data |

|

|

| Brettschneider et al. (2020), Germany | To assess the cost-effectiveness of SCM versus TAU in treating depression |

|

Prospective cluster RCT |

|

|

| Chatterton et al. (2019), Australia | To evaluate the economic feasibility of SCM in managing childhood anxiety disorders |

|

RCT comparing SCM to a validated, manual treatment |

|

|

| Collins et al. (2020), Ireland | To evaluate the effectiveness of a stepped care primary care psychology service | Data from:

|

A mixed method study with repeated measures for clinical outcomes and an online and postal survey with quantitative and qualitative elements |

|

|

| Delgadillo, Gellatly, and Stephenson-Bellwood (2015), England | To investigate factors influencing clinician decisions to prolong or conclude treatment in cases with little evidence of therapeutic gains |

|

Cross-sectional survey |

|

|

| Franx et al. (2012), the Netherlands | To explore clinicians' insights on their experience with the SCM |

|

Qualitative study |

|

|

| Goorden et al. (2014), the Netherlands | To determine societal costs of SCM & CAU in treating panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder in primary care |

|

Two-armed cluster RCT |

|

|

| Haugh et al. (2019), United States | To explore patients' and clinicians' general attitudes towards SCM, the individual steps and the treatments offered within each step |

|

Cross-sectional survey |

|

|

| Hermens et al. (2014), the Netherlands | To examine the gap between CAU and SCM care and explore facilitators and barriers that affect provision of SCM |

|

Exploratory qualitative study |

|

|

| Hopkins et al. (2021), Australia | To understand consumers' needs and experiences in navigating SCM services in their mental health journey. |

|

Qualitative study |

|

|

| Kampman et al. (2020), the Netherlands | To compare outcomes of SCM versus CAU in treating panic disorder |

|

RCT |

|

|

| Lee et al. (2021), Australia | To explore the cost-effectiveness of a Dutch SCM intervention for treating depression and/or anxiety when adapted to the Australian context |

|

A model-based cost utility analysis |

|

|

| Maehder et al. (2021), Germany | To explore collaboration within SCM |

|

Qualitative process evaluation of a cluster RCT |

|

|

| Muntingh et al. (2014), the Netherlands | To evaluate the effectiveness of SCM for treating anxiety disorders in adult primary care patients |

|

Pragmatic cluster RCT |

|

|

| Oosterbaan et al. (2013), the Netherlands | To explore collaborative SCM and CAU for common mental disorders |

|

Cluster RCT |

|

|

| Salomonsson et al. (2018), Sweden | To examine SCM in treating participants with highly prevalent disorders in primary care by:

|

|

RCT |

|

|

| Silverstone et al. (2017), Canada | To examine if screening patients for depression in primary care and then treating them with different modalities was better than CAU alone. |

|

RCT |

|

|

| Yan et al. (2019), Canada | To analyse cost-effectiveness of a randomised study of depression treatment options in primary care |

|

RCT |

|

|

- Abbreviations: ACE, Assessing Cost-Effectiveness model; ACQ, Dutch versions of the Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; CAU, Care as Usual; CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression of Improvement Scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale; CSC, Collaborative Stepped Care; DALYs, Disability-adjusted life years; EQ-5D, EuroQol; EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version as an effect measure; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5-dimension with a five-level scale; FARAH-Q, Factors Associated with Referral And Holding Questionnaire; GAD7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; HRQoL, PHQ-9 Health-related quality of life; MADRS-S, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale-Self Rated; OASIS, Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; OQ-45, The Dutch version of the Outcome Questionnaire-45; PAS, The Dutch version of the Panic and Agoraphobia Scale; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; Pragmatic cluster RCT, Pragmatic cluster randomised control trial; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; QALY, Quality-adjusted life years; RCBT, Regular cognitive behavioural therapy; RCT, Randomised control trial; SF-HQL, Health and Labor Questionnaire; TAU, Treatment as Usual; TiC-P, Questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric Illness; Trimbos/IMTA, Trimbos/IMTA; WTP, Willingness-to-pay.

2.5 Data Analysis

A descriptive methodology was employed to analyse the information captured in literature data charting Table 1. This approach encompassed a rudimentary coding method to facilitate organisation and categorisation of the data (Pollock et al. 2021). The subsequent section expounds upon the outcomes of the thematic analysis more comprehensively.

3 Results

The thematic analysis of the literature collected yielded five key themes related to delivering primary mental health care, based on SCM. These are (1) SCM versus other CAU options, (2) cost-effectiveness of SCM, (3) operationalising SCM, (4) collaboration within SCM and (5) stakeholders' experience of SCM. The following subsections discuss these themes in further detail.

3.1 Theme 1: SCM Versus Other CAU Options

Four papers included in this review compared SCM to alternative models of care delivery adopted in primary care, such as Care as Usual (CAU), also called Treatment as Usual (TAU) (Apil et al. 2014; Kampman et al. 2020; Muntingh et al. 2014; Silverstone et al. 2017). Such CAU or TAU models are defined as primary care psychological support provided by clinicians or organisations who do not use a SCM approach (Grenyer et al. 2018).

Muntingh et al. (2014) evaluated the effectiveness of SCM versus CAU in treating the anxiety symptoms of adult primary care patients with a DSM IV diagnosis of panic disorder or generalised anxiety disorder, using a pragmatic cluster random control trial (RCT). Based in the Netherlands, 180 patients were included in the study, of whom 114 received SCM care and 66 received CAU. At 12 months, CAU patients showed deteriorating anxiety as opposed to sustained improvement shown by the SCM patients, with no notable differences in response and remission rates. The study concluded that SCM proved to be more effective in alleviating anxiety symptoms than CAU.

Also based in the Netherlands, Kampman et al. (2020) evaluated the effectiveness of SCM versus TAU in treating panic disorder in 128 participants, using an RCT. The SCM approach involved a 10-week guided self-help programme (in a pen-and-paper format), followed by, if necessary, a 13-week structured face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), with medication, if prescribed, remaining unchanged. The TAU treatment consisted of a 23-week standard face-to-face CBT, with medication, when prescribed, also maintained at a constant level. Consistent with findings by Muntingh et al. (2014), the results from Kampman et al. (2020) showed that 74.4% of the patients who accessed SCM remitted, compared to 53.3% who accessed CAU. However, SCM had a dropout rate twice that of the TAU option, and the second phase of the SCM did not yield significantly improved outcomes.

In their study carried out in the Netherlands, Apil et al. (2014) compared the effectiveness of the SCM versus CAU in preventing relapse, also using an RCT. The study involved 136 participants who had suffered at least an episode of major depression in the past and had received mental health treatment through an SCM approach or a CAU approach. The SCM approach encompassed four stages: (1) watchful waiting, (2) bibliotherapy, (3) individual cognitive behavioural therapy and (4) indicated treatment. The CAU option entailed either psychotherapy from a mental health clinician with or without prescription of antidepressant medication from their GP or other mental health practitioners. The primary outcome measure was the incidence of a new depressive episode. In contrast to Muntingh et al. (2014) and Kampman et al. (2020), the study by Apil et al. (2014) found the SCM approach was not more effective than CAU in preventing relapse of depression. Also, the study highlighted that though ‘watchful waiting’ may be a common initial step in SCM services, its appropriateness in high-risk populations is contentious as it delays treatment, leading to further deterioration before accessing care.

Silverstone et al. (2017) examined whether depression outcomes in adults attending family practice improved by SCM versus TAU, also using an RCT. Based in Canada, the study involved 1489 participants randomised across four groups, over 12 weeks. Group #1 consisted of controls who underwent PHQ-9 assessment with results not shared and Group #2 underwent screening followed by TAU. Group #3 underwent screening followed by both TAU and access to an online cognitive CBT programme, and Group #4 utilised an evidence-based SCM for depression. The results suggest that a considerable proportion of mild depression identified in primary care tends to naturally resolve and that the patient's model of care or intervention does not appear to make any difference. The findings challenge the belief that more complex treatment programmes or pathways, such as the SCM, result in better depression outcomes in primary care settings. It does, however, acknowledge that the limited participation of clinics resulted in only one clinic taking part, which uses the SCM. This resulted in a smaller participant group and may have impacted the results.

3.2 Theme 2: Cost-Effectiveness of SCM

Six papers focused on the cost-effectiveness of the SCM in treating mental illness (Brettschneider et al. 2020; Chatterton et al. 2019; Goorden et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2021; Salomonsson et al. 2018; Yan et al. 2019). This aspect has received more attention in recent years due to the growing mental health needs of communities in contrast to the limited resources available for mental health services within health systems. This theme describes the costs associated with the SCM compared with other CAU models in primary mental health.

Based in Sweden, Salomonsson et al. (2018) examined SCM in treating 396 participants with common mental disorders, using RCT. Findings showed a significant reduction in symptoms for highly prevalent mental health disorders with 40% of patients with clinical baseline ratings achieving remission after 9 weeks of guided self-help. Findings also showed an additional positive impact of face-to-face treatment for those who did not respond initially, with 39% of these patients' attaining remission. The study concluded that SCM proves to be successful and cost-effective in managing highly prevalent mental health issues in primary care, resulting in notable remission rates.

Lee et al. (2021) explored the cost-effectiveness of a Dutch collaborative SCM for treating highly prevalent disorders in Australia, by applying a model-based cost utility analysis to an RCT by Oosterbaan et al. (2013). The SCM had a step-by-step approach of guided self-help with a mental health nurse at a primary care clinic and a step-up referral to specialised mental healthcare. Outcomes were measured in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) resulting from remission of symptoms. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated in 2019 Australian dollars ($AUD) for each DALY prevented. In line with Salomonsson et al. (2018), this study indicated that SCM adoption has a very high probability, 99.6%, of being cost-effective in Australian primary care, compared to CAU. The stability of ICERs remained largely unaffected by variations in model parameters and assumptions.

Goorden et al. (2014) explored the societal costs of using SCM in treating highly prevalent disorders in the Netherlands, using a two-armed cluster randomised controlled trial (CRCT). The study included 43 primary care practices with 180 patients: 114 for collaborative SCM and 66 for CAU. As a measure of societal costs, both indirect productivity costs and productivity costs related to the absence of work were found to be less in the SCM recipients compared with CAU. Combined with the results from Lee et al. (2021) and Goorden et al. (2014), the study's findings provide further justification for the adoption of the SCM in the delivery of primary mental health care.

Chatterton et al. (2019) evaluated the economic feasibility of SCM in managing childhood anxiety disorders in 281 young Australians aged 7–17 with a diagnosed anxiety disorder, also using RCT. The study compared the SCM approach to a validated clinician-delivered CBT programme. It reinforced the societal benefits with findings that it was less costly to deliver from a societal perspective. Though clinical outcomes and health system costs seem comparable across SCM and CAU, factoring in caregivers' time introduced a significant difference. In tandem to societal benefits findings by Goorden et al. (2014), the results revealed that implementing SCM cost $198 lower from a societal perspective than the CAU, primarily due to the reduced cost of parental time required for its delivery.

Yan et al. (2019) performed a cost-effectiveness analysis of SCM versus TAU, and online CBT, for treating depression in adults in a randomised study. The Canadian-based analysis of 1400 participants found no clinically significant differences between the two; however, concluded that a more expansive SCM approach could result in substantial cost savings in overall healthcare expenses compared to the standard treatment. Though additional efforts should determine the most clinically effective iterations of an SCM, the results imply that the SCM pathway holds significant potential to enhance the value of the healthcare system by exhibiting a lower incremental cost-effectiveness ratio compared to both treatments as usual and online-based cognitive behavioural therapy. This result is parallel to the findings of Lee et al. (2021).

The German-based Brettschneider et al. (2020) study also examined the cost-effectiveness of the SCM approach in comparison with treatment as usual, using a prospective cluster RCT. The study included 737 patients with depression. The intervention group received services from a stratified four-step SCM and collaborative care programme, including GPs, psychiatrists, psychotherapists and psychiatric inpatient units. Step 1 involved active monitoring, and Step 2 utilised bibliotherapy, internet-based self-care and telehealth psychotherapy. Step 3 consisted of outpatient psychotherapy or antidepressant medication, and Step 4 involved a blend of psychotherapy and medication. In contrast, the CAU received approved care outside the SCM, including outpatient and inpatient psychotherapeutic or psychiatric services. In contrast to results from Salomonsson et al. (2018), the study found service costs to be higher in the SCM than in the CAU. The study, however, acknowledges the differences in SCM implementation, which could explain the differences in findings compared with other studies and, as such, indicates the need to analyse various implementation adaptations of the SCM.

3.3 Theme 3: Operationalising the SCM

Three studies focused on explicating the implementation and operationalisation of the SCM, elucidating different permutations and approaches that can be adopted to effectively facilitate the delivery of care in practical settings (Boyd, Baker, and Reilly 2019; Delgadillo, Gellatly, and Stephenson-Bellwood 2015; Hopkins et al. 2021).

Based in England and including 82 clinicians comprising mental health nurses, counsellors and psychotherapists, the qualitative study using FARAH-Q questionnaires explored factors influencing patient discharge during care episodes (Delgadillo, Gellatly, and Stephenson-Bellwood 2015). Findings revealed a four-factor decision-making process shaped by nuanced interactions of beliefs, attitudes, subjective norms and self-efficacy. Correlation analysis demonstrated that the likelihood of holding patients in treatment increases when: There are perceived obstacles to referring the patient for additional treatment, the therapist has a positive relationship and therapeutic alliance with the patient, and the therapist is confident in achieving a positive outcome by extending the treatment. Besides evidence-based practices and guidelines, the clinician's decision-making process within the SCM are strongly influenced by beliefs, norms and attitudes.

Boyd, Baker, and Reilly (2019) used an observational study to explore the impact of a progressive SCM in improving access to psychological intervention services. In stratified SCMs, the assessing, intake clinician determines the level of care that the patient needs. In progressive SCMs, clinicians provide initial low-intensity treatment, with the patient stepping up if there is no improvement. The study analysed retrospective data of 16 723 patients over a period of 4 years period in an IAPT service in England, comparing the outcomes of patients who completed treatment in a stratified SCM and a progressive SCM. The study found that patients in the progressive SCM were up to 1.5 times more likely to attain improvement. However, the authors highlighted comparing outcomes and assessing the model's overall effectiveness is made more difficult because of the diverse definitions and variations in the implementation of the model in research and routine practice.

Based in Australia, Hopkins et al. (2021) qualitative study explored the experience of patients diagnosed with severe mental illness, who accessed different nonacute mental health services within the SCM. Involving 18 patients across various community facilities, the study presented results contrary to those of Boyd, Baker, and Reilly (2019). Noting patients' nonlinear progression within the SCM, the findings emphasised the need for a tailored model, which aligns with policy imperatives for person-centred care and will shorten the recovery period of individuals with severe mental illnesses. A dynamic model will enable flexible access and transition between services in response to changes in patient's mental health status.

3.4 Theme 4: Collaboration Within SCM

Three papers explored collaboration within the SCM delving into the intricacies of collaborative efforts within the model and scrutinising the dynamics, strategies and implications associated with interprofessional cooperation (Hermens et al. 2014; Maehder et al. 2021; Oosterbaan et al. 2013).

Hermens et al. (2014) conducted an explorative study on SCM implementation for depression, involving 6 GPs and 22 primary mental health clinicians. Based in the Netherlands, the study's findings highlighted the collaboration of GPs and other mental health practitioners at both the clinician's level and systemic level, as a defining criterion for optimal care. This would facilitate sharing seamless and effective communication, such as discharge summaries and patient referrals.

Maehder et al. (2021) conducted a process evaluation of a CRCT focusing on collaborative SCM compared to CAU. Based in Germany, the qualitative study involved 24 participants, comprising various primary mental health clinicians. They found that effective collaboration within SCM care, is characterised by regular interprofessional communication, expedited referrals and streamlined care processes. Reinforcing the perspectives indicated by Hermens et al. (2014), the study also offered valuable suggestions for enhancing collaboration, emphasising the establishment of localised networks, the integration of additional professions and the augmentation of mental health care resources and compensation, particularly in collaborative endeavours.

Based in the Netherlands, Oosterbaan et al. (2013) used CRCT to explore collaborative SCM and CAU among 20 GPs and 8 psychiatric nurses in high prevalent disorders care. Collaborative SCM improved response and remission rates by up to 4 months compared to CAU. In parallel to findings from Hermens et al. (2014) and Maehder et al. (2021), the study indicated that improved collaboration within the SCM between healthcare providers benefited all stakeholders. In addition, patients favoured the collaborative approach compared to CAU.

3.5 Theme 5: Stakeholders' Experience of SCM

Four papers focused on the experience of stakeholders involved with the SCM, namely patients accessing care, clinicians working within the SCM and clinicians referring patients to the SCM (Anderson et al. 2020; Collins et al. 2020; Franx et al. 2012; Haugh et al. 2019).

Collins et al. (2020) conducted a mixed-methods 360° evaluation of stepped care psychotherapy, involving data from 34 referrers and 125 patients. By triangulating the data, the study provided an in-depth understanding of SCM. Patients expressed significant satisfaction with the service, highlighting therapists' interpersonal qualities and customising service delivery as key elements. Referring clinics expressed high overall satisfaction with the SCM, emphasising the promptness of response to referral and the duration of intervention as crucial. This study illustrates that the overall interpersonal experience often holds more significance in evaluating a service than clinical outcomes.

Franx et al. (2012) Netherlands-based qualitative study used semi-structured group interviews to explore clinicians' insights on their experience with the SCM. In general, SCM was well-received. Clinicians identified quality improvement cycles, the importance of local support structures, the model's implementation locally and multidisciplinary team meetings, as contributing to SCM's success. However, they also identified barriers such as poor information systems, conflicting clinical views among the MDT and limited resources. Overall, SCM was well-received, with clinicians highlighting the importance of structured improvement processes after implementation, identifying changes and generating solutions.

Anderson et al. (2020) Australian codesign and feasibility study involving 32 GPs, 22 practice staff and 418 patients, found the SCM to be acceptable. Echoing the findings of Collins et al. (2020), participants commended key processes such as intake, monitoring and feedback, while GPs found the model to assist in recognising and addressing prevalent mental health issues among their patients. These findings hold implications for both policy development and the implementation of the SCM in Australian primary mental health care.

Haugh et al. (2019) conducted a cross-sectional survey to explore patients' and clinicians' attitudes towards various elements of Structured Clinical Management (SCM) in treating depression, involving 141 patients and 32 clinicians from the northeastern United States. In line with evidence from Collins et al. (2020) and Anderson et al. (2020), both parties perceived the SCM as acceptable and an improvement on CAU. However, there were distinct preferences within the model in this study, with clinicians favouring a combination of psychotherapy and medication, while patients preferred psychoeducation and self-help.

4 Discussion

Primary health care remains a significant aspect of mental healthcare delivery in most nations (World Health Organization [WHO] 2022). This scoping review explored various elements of SCM by examining the existing literature on the delivery of primary mental health services based on the model. A total of 20 papers were included, with four papers comparing SCM to other CAU options, six papers exploring the cost-effectiveness of SCM, three papers focusing on implementing and operationalising SCM, another three papers exploring collaboration within SCM, and four papers focusing on consumers' and clinicians' experiences of SCM.

Studies have highlighted how the SCM is an innovative alternative to CAU treatments (Muntingh et al. 2014; Kampman et al. 2020). Focusing on anxiety disorders, these studies reveal a striking commonality: A significant improvement observed in individuals with mental illnesses engaging with the SCM. What sets these findings apart from CAU treatment, is the presence of self-help options within the SCM framework. This factor emerges as a noteworthy and shared element contributing to positive outcomes in both investigations. This shared emphasis on self-help resources within the SCM aligns with contemporary approaches in mental health care (Haugh et al. 2019). The self-help approach underscores the model's adaptability and effectiveness in catering to the diverse needs of individuals experiencing anxiety disorders (Kampman et al. 2020). This common thread not only emphasises the promising nature of the SCM but also suggests that its innovative features, particularly the incorporation of electronic self-help components, are likely to play a pivotal role in fostering positive therapeutic outcomes within anxiety disorders.

Despite Muntingh et al. (2014) and Kampman et al. (2020) highlighting the advantage of the SCM over CAU there remains a need for further evidence to prove SCM's superiority over CAU options (Apil et al. 2014; Silverstone et al. 2017), neither study indicated that SCM resulted in better outcomes. The primary mental health landscape's complexities necessitate more comprehensive comparative analyses, considering the different variables such as patient diagnosis, treatment modalities, service locations and variations in the implementation of the model (Brettschneider et al. 2020). In addition, the noted advantages of the SCM could vary based on the specific mental health condition being addressed, the severity of symptoms and the characteristics of the patient population. This makes establishing the SCM's superiority across diverse contexts a complex undertaking that requires thorough investigation (Boyd, Baker, and Reilly 2019). Therefore, further research is warranted to determine whether the SCM consistently leads to superior treatment outcomes compared to various TAU options. Rigorous comparative studies that carefully consider different patient profiles, diagnostic categories and treatment modalities are essential (Boyd, Baker, and Reilly 2019). The authors highlight that it is imperative for such research to delve into the nuances of patient experiences, engagement and short- and long-term outcomes to provide a comprehensive assessment of positive outcomes that can be linked to the SCM.

Recent years have seen an increased focus on the cost-effectiveness of employing models without sacrificing the quality of care in the treatment of mental illness. This is driven by escalating mental health demands within communities and the inherent limitations in resources allocated to mental health services within broader health systems (Chatterton et al. 2019). The balance between the optimum allocation of resources while ensuring high-quality mental health care has prompted a revaluation of existing treatment models. Studies in this review have positively reported on the cost-effectiveness of the SCM across diverse mental health settings (Chatterton et al. 2019; Goorden et al. 2014; Salomonsson et al. 2018). These studies provide valuable insights into the economic viability of the SCM, emphasising its potential to offer efficient and economical mental health interventions. Furthermore, with its tiered and flexible approach to care delivery, SCM not only aligns with the evolving needs of diverse mental health conditions but also proves economically advantageous (Chatterton et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2021). By providing a spectrum of interventions tailored to the severity of individual cases, the SCM demonstrates the potential of optimising resource allocation without compromising the quality of care.

Yet, some studies question the model's cost-effectiveness. Brettschneider et al. (2020) found no evidence for the cost-effectiveness of the SCM in comparison to treatment as usual. Using quality-adjusted life years (QALY) as an effect measure, their study argues that cost-effectiveness assessment considers broader factors than just the direct benefits to the patient. Rather, the expense implications to society and the health system should also be considered. This knowledge is crucial in supporting and shaping policy and the decision-making process, especially in the context of finite resources (Brettschneider et al. 2020). Though most of the studies in this review indicate that the SCM is cost-effective in delivering mental health services, there is a need to exercise caution when concluding, as most studies focused on specific components or settings rather than the entire SCM (Chatterton et al. 2019). Lee et al. (2021) support this notion by indicating that the SCM has the potential to be more cost-effective than traditional models. However, the author also states modifications may be required to adjust to the local healthcare systems to enhance comprehension of the practical cost-effectiveness of SCM in various settings. Yan et al. (2019) also caution to consider administration and setup costs, as these are often overlooked but may significantly impact cost-effectiveness. Overall, there is a need for a more comprehensive evaluation of cost-effectiveness that considers not only short-term savings but also potential long-term benefits. Such evaluation should consider the best practice guidelines and the various implementation variables of the SCM (Lee et al. 2021).

This review also uncovered variations in implementing and operationalising the SCM. These variations may not be weaknesses, as there is a need for the SCM to respond to the local needs, challenges, resources and opportunities. According to DoH (2018), variations in local approaches align with the objective of the Australian Government which intentionally established the commissioning bodies known as primary health networks. These organisations are mandated to ensure the delivery of the SCM in a way that addresses the specific gaps in services at the local level (DoH 2018). There is, however, a need for organisations and professionals involved to understand the SCM approach that they are adopting. Such shared clarity will ensure smooth care delivery. It will also ensure that clinicians provide an adequate number of sessions and, where required, referrals to other services are made in a timely and seamless manner that improves the overall effectiveness of the SCM (Delgadillo, Gellatly, and Stephenson-Bellwood 2015).

Boyd, Baker, and Reilly's (2019) investigation into operationalising the SCM, particularly the impact of a progressive SCM on enhancing access to psychological intervention services, offers valuable insights and prompts significant considerations for the literature review's discussion. The study critically distinguishes between the stratified and progressive SCM variations. Notably, the study highlights a critical gap in the existing evidence concerning the effectiveness of the SCM delivery model. The diversity in definitions and variations in the model's implementation, both in research and routine practice, poses challenges for comparing outcomes and comprehensively assessing the model's overall effectiveness. Overall, though, there is support for the effectiveness of the treatment options used in the SCM. Further exploration is required, especially in analysing the implementation of the SCM. Such research should focus on the approach adopted in implementing the model, the resources required at each step, and the interventions that yield the most desirable impact.

Three noteworthy studies by Oosterbaan et al. (2013), Hermens et al. (2014) and Maehder et al. (2021) examined the theme of collaboration within the SCM. Hermens et al. (2014) underscored the importance of collaboration, not merely as a factor but as a defining criterion for optimal care, at both the clinician and systemic levels. This systemic collaboration is crucial for fostering seamless communication, including exchanging information such as discharge summaries and patient referrals. Maehder et al. (2021) also emphasised the role of collaboration in effective SCM care. They provided valuable suggestions for improving collaboration, including establishing localised networks, integrating additional professions, and augmentation of mental healthcare resources and compensation, particularly in collaborative endeavours. The research by Oosterbaan et al. (2013) revealed that enhanced cooperation among healthcare providers, a key distinctive feature of the SCM, was preferable and yielded positive outcomes for all parties. These studies contribute nuanced perspectives on the significance and potential enhancements of collaboration within the SCM framework, emphasising the need for a comprehensive and systemic approach to achieve optimal care outcomes.

Finally, this review has incorporated stakeholder experiences within the SCM, considering insights from patients, clinicians within the SCM, and those referring to it. Across all studies, the SCM emerged as universally acceptable (Franx et al. 2012; Anderson et al. 2020; Collins et al. 2020; Haugh et al. 2019). Patients' satisfaction was intricately linked to the qualities of their therapeutic relationships with clinicians and the extent to which the service was tailored to their specific needs, highlighting the importance of service customisation (Collins et al. 2020). Referring clinics also expressed satisfaction, particularly appreciating the SCM's prompt response to referrals, as emphasised by Collins et al. (2020). A noteworthy revelation from this study is that interpersonal experiences often hold greater significance in service evaluation than clinical outcomes alone. Furthermore, Franx et al.'s (2012) study accentuated the positive SCM experience for clinicians, who value quality improvement cycles and local support structures as critical contributors to the SCM's success. These nuanced insights contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of stakeholder perspectives on the SCM, paving the way for informed policy decisions and further advancements in the implementation of the model.

5 Gaps in Research

This review has identified a paucity of research in several areas. First, the existing literature on SCM reveals a consistent oversight in acknowledging the roles of caregivers, families and natural supports in the care process, an ongoing issue that has been identified in mental health (Happell et al. 2017). Despite being recognised as integral to the SCM (DoH 2019), there is an absence of evidence detailing this. Consequently, the authors noted a gap in evidence outlining the extent and significance of their involvement, emphasising the need for research to investigate their roles within the SCM. Exploring the role of carers in the SCM presents an opportunity to enhance overall outcomes, emphasising the importance of their inclusion in the research agenda.

Secondly, integrating the SCM into the broader mental health system remains lacking in comprehensive research. While the SCM shows potential in areas covered in this study, the integration of this model into the existing Australian healthcare systems remains insufficiently explored (Chatterton et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2021). Research should include the challenges of embedding the SCM within the broader system, and examining organisational and systemic barriers that hinder integration. In addition, strategies to foster collaboration among stakeholders in the ecosystem require thorough investigation to facilitate the model's effective incorporation into existing systems.

Thirdly, there is also a lack of studies that have delved into the roles of various healthcare professionals delivering care under the SCM. Understanding the nuanced roles and responsibilities of professionals such as mental health nurses, psychologists, occupational therapists and social workers within the SCM is crucial for optimising its implementation and efficacy. Future research endeavours should prioritise investigating and documenting these roles, shedding light on how interdisciplinary collaboration can be leveraged to enhance the delivery of mental health services within the SCM framework. Such insights will not only deepen the understanding of the model but also provide practical guidance for policymakers and organisations seeking to enhance the SCM.

Lastly, there is a notable dearth of research on the application and efficacy of the SCM in Australia. Despite the nationwide adoption of the SCM, there is a significant gap in understanding the implementation and outcomes of SCM interventions in the Australian context. This gap is crucial given Australia's distinct healthcare landscape and diverse population needs. Research should investigate various factors influencing the implementation and effectiveness of the SCM in Australia. Addressing these research gaps is imperative for informing policies, advocating evidence-based practices and improving mental health outcomes for individuals nationwide.

6 Conclusion

This scoping review investigated the application of the SCM within primary mental health, aiming to scrutinise the existing literature on this model of service delivery. Numerous critical elements have emerged in the examination of 20 papers, shedding light on key aspects of the SCM's implementation, efficacy and impact. There is a paucity of studies that examine elements such as the effectiveness of different steps within the SCM, the role of caregivers and the overall patient experience within the model. While the SCM holds promise for optimising resource allocation and enhancing the efficiency of mental health service delivery, some of the critical areas that require further exploration have been highlighted. This imperative is accentuated by the evolving landscape of mental health care, calling for an in-depth understanding of the nuanced dynamics and contextual factors that influence the success of the SCM in diverse primary care settings.

7 Relevance to Clinical Practice

In essence, this scoping review highlights the current state of knowledge regarding the SCM and emphasises the crucial avenues for future research, particularly in the Australian context. Despite the national implementation of the SCM from 2016 onwards, research on its implementation, operationalisation and effectiveness in Australia has been notably scarce. This review is relevant in advancing knowledge and clinical practice in primary mental healthcare settings, offering valuable insights for policymakers, PHNs, service providers and clinicians. The findings from the review provide an opportunity for these stakeholders to refine their approaches and stay informed about the latest developments in SCM implementation. The identified gaps in existing studies are particularly informative as starting points for recognising areas where the SCM may require improvement. The call for further research aligns with a commitment to continuous quality improvement and evidence-based, patient-centred care. This proactive stance towards ongoing enhancement and refinement of mental healthcare services is needed in the face of ever-increasing mental health service delivery needs in Australia, and beyond.

Author Contributions

S.M. led the idea conception, project design, spearheaded literature search and manuscript write up. M.O. provided project oversight, literature search, selection of articles, reporting of results, manuscript review and contributed to discussions. L.Z. contributed to manuscript review, literature search and discussions. M.C.W. participated in manuscript review, literature search and discussions. All authors involved in this manuscript have met the authorship criteria and have unanimously consented to the final version.

Acknowledgements

An Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Fee-Offset Scholarship through Federation University Australia supports S.M. S.M. acknowledges that the ‘Babe’ Norman Scholarship award, funded by the Rosemary Norman Foundation and administered by the Australian Nurses Memorial Centre, is facilitating his postgraduate studies. Open access publishing facilitated by Federation University Australia, as part of the Wiley - Federation University Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.