Experiences of Respite Care Among Carers or Relatives Who are Responsible for Caring for Individuals With a Mental Illness: An Integrative Literature Review

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

An integrative review methodology was employed, following PRISMA guidelines and Whittemore and Knafi's method for integrative review. Thus, the review synthesised the findings of empirical literature published between 2005 and 2023 drawn from four databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Scopus. From the seven studies that met the inclusion criteria, a number of themes emerged: (a) relief of carer burden; (b) benefits for individuals with Mental Illness (MI); (c) barriers to accessing respite care; and (d) inappropriate services model for respite care for individuals with MI. The review findings indicate that using respite care services can decrease a carer's burden and can positively impact both carers and individuals with MI. Conversely, respite care may cause an increase in carers' stress levels due to the lack of service availability, insufficient knowledge and understanding about respite care services for carers, respite accessibility challenges accessible for people with MI and the reluctance of people with MI to accept respite care.

1 Introduction and Background

On a global scale, mental illnesses (MIs) are surpassing the incidence of physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and cancer (Vigo, Thornicroft, and Atun 2016). Globally, 5% of the population have reported living with depression, while 3.8% have reported living with an anxiety disorder (World Health Organization [WHO] 2021). Furthermore, it is estimated that approximately 20 million people worldwide are diagnosed with schizophrenia (WHO 2019). MI can result in significant disabilities in comparison to other disorders (Brighton et al. 2016). People with MI may experience severe anxiety, feel suicidal or have psychotic episodes, all issues that can cause psychosocial disability (Steele, Maruyama, and Galynker 2010).

Individuals with MI frequently require support and in many circumstances receive this support from carers (Brighton et al. 2016). Many people provide care for others, and the term informal carers is used to refer to those who offer unpaid care to family members or acquaintances with a disability, MI or chronic condition (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2021). Being a carer for people with MI can demand a high level of responsibility from close relatives or friends, in terms of helping with everyday living. As a result of the changes in life circumstances and dramatically varying symptoms among people with MI, these carers take on considerable obligations (Brighton et al. 2016).

Major responsibilities taken on by carers can result in carer burden—which Platt (1985), a leader in carer burden research, defined as the difficulties that impact the carer's life while taking care of loved ones. Carer burden can occur for many reasons, but Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson (2005) suggest the responsibility for financial and social costs that fall on the carers is a major source. According to Kavanagh (1992), carers' burdens can be considered objective and subjective. The objective viewpoint is concerned with the behaviour of the individual with MI and how it affects the carer's health, along with economic and social activities. The subjective perspective is taken to mean the carers' reactions, such as grief or humiliation.

Caring for someone with MI can negatively influence the health and well-being of the carer. For example, in terms of an objective burden, carers may experience physical and psychological stress that in turn, leads, to cardiovascular disease, cancer, depression or persistent anxiety (Galla et al. 2015). According to Carers UK (2021), one in four UK adults provided unpaid care for their ill relatives or friends in 2020. Moreover, 25% of carers reported having a physical health problem, and 30% suffered from mental health issues. Carers may also experience mental distress while providing care. For example, one study revealed that 40% of carers for people with MI were themselves living with MI (Östman and Hansson 2004). Additionally, as Brighton et al. (2016) observed, carer burden also impacts leisure activities, meaning that informal carers frequently do not participate in recreational activities because such pastimes may conflict with their caring responsibilities.

Among the potential solutions to the problem of carer burden, respite care offers a practical way to help reduce the burden of caregiving (Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson 2005). Along these lines, there has been study of the impacts of informal carers' use of respite care (see, e.g., Strunk 2010; Vandepitte et al. 2016; Yoong and Koritsas 2012). However, many of the studies on this topic have focused on the implications of using respite care for those who care for people with physical disabilities or various forms of dementia (Strunk 2010; Vandepitte et al. 2016), not MI.

Greater understanding of the effects of respite care for both carers and people with MI is needed. Accordingly, this integrative literature review focuses on the experiences of using respite care among carers or relatives who are responsible for caring for individuals with MI.

2 Methods

This integrative review follows the guidelines and strategies framework suggested by Whittemore and Knafl (2005). This framework enables the accomplishment of a comprehensive meaning of a phenomenon by synthesising past research on that phenomenon. Five major stages form the framework: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation of results. This approach also follows Christmals and Gross (2017) in utilising a thematic analysis for data analysis.

2.1 Problem Identification

Caring for people who live with MI (consumers)—can cause what is often known as carer burden, which can have negative physical and psychological impacts on carers due to the associated stress. Respite care has the potential to decrease the burdens or fatigue carers experience from caring for consumers with MI (Lund et al. 2014). Respite care refers to any intervention aimed at providing rest or relief to carers (Maayan, Soares-Weiser, and Lee 2014). The study was based upon the research question: What are the experiences of using respite care among carers or relatives who are responsible for caring for individuals with MIs?

2.2 Literature Search (Search Strategy)

The researchers established that studies eligible for inclusion in the review must have reported primary quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods data and have been published in English between January 2005 and May 2023. The initial date of 2005 was chosen as the last substantive literature review was published by Jeon and her colleagues in that year (Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson 2005).

This study's inclusion criteria selected studies that reported participants aged 18–65 years who were caring for a person as an adult aged 18 years or over with a primary diagnosis of MI as eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if the primary focus was on carers for participants with a physical health condition or disability, children (age <18), carers for people with substance use disorders, elderly people patients with Alzheimer's or ‘cognitive impairment’ or ‘memory loss’ and/or dementia. Finally, the reported focus of the study must have included the experiences of informal carers regarding respite care services.

A systematic search process using electronic databases was conducted to identify studies that were relevant to the research question. This process began with a preliminary search that was carried out to assist in keyword selection and question refinement. An initial review of the articles that emerged in this primary search revealed that using the terms ‘carer’, ‘mental health condition’ and ‘respite care’ proved unhelpful in finding useful articles.

As a different approach, various combinations of these terms were used along with asterisks (‘*’) to expand the search terms, resulting in the broadest selection of research literature (Table 1).

| Search strategy | |

|---|---|

| Population | Carer* OR caregiver* OR family OR relative |

| Intervention | respite OR ‘short care’ OR ‘short-term care’ |

| Context | mental OR psychiatric |

| Outcome | benefit OR importance OR impact OR effect OR “quality of life” |

| NOT (dementia OR alzheimer* OR children OR ‘physical* Disab*’) | |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Sources | Books; grey literature |

| Language | Papers published in languages other than English |

| Timeframe | Papers published before 2005 |

| Geographical location | Nil |

| Types of studies | Secondary research; Systematic reviews |

| Types of participants |

Children under the age of 18 or adults over 65 years NOT (dementia OR alzheimer* OR children OR ‘physical* Disab*’) |

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Sources | Primary research; published in peer-reviewed journals |

| Timeframe | Publication date 2005–2021 |

| Geographical location | All geographical areas included |

| Types of participants | Adult's aged 18 to 65 years, caring for people with mental illness |

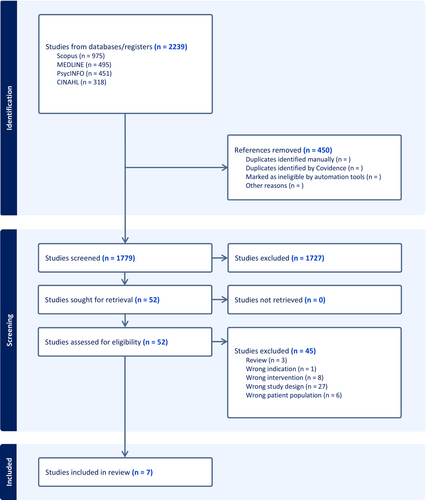

The electronic databases used for the literature search included the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), SCOPUS and PsycINFO (Psychology). MEDLINE and CINAHL they are recognised nursing and health focussed databases. Meanwhile, the American Psychological Association's PsycINFO, which offers an optimal resource for locating psychological literature, was used to identify the impacts of respite care in carers of people with MI. In addition, a search was performed using Google Scholar with the same search terms and fields (Figure 1).

The screening was conducted using Covidence Systematic Review Software. A total of 2239 references were initially included for screening, representing 2239 individual studies. After removing 450 duplicate articles, 1779 studies remained. Each article was reviewed by two authors. These studies underwent evaluation based on their title and abstract, with a primary focus on respite care for mental health.

Specific attention was given to respite care for individuals with mental health conditions. Studies involving children with disabilities, particularly intellectual or developmental disabilities, as well as investigations related to cancer, HIV/AIDS, stroke, neurological disorders such as Parkinson disease and multiple sclerosis, and other terminal illnesses were excluded from the analysis.

Among the 52 studies assessed for full-text eligibility, 45 studies were excluded due to inappropriate study design (n = 27), incorrect intervention (n = 8), incorrect patient population (n = 6), not being primary studies (n = 3) and incorrect indication (n = 1). Ultimately, seven studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis, focusing solely on respite care for mental health.

The main aim of the analysis was to focus solely on primary research studies to ensure a more direct examination of the original data and findings. This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the specific research topic or questions at hand. Table 2 provides a summary of the articles.

| References | Title | Journal | Vol./no./ pages | Country | Study aims | Sample characteristics (n) Total: and sitting | Study design | Data collection | Data analysis | Findings and limitation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brighton et al. (2016) | The effect of respite services on carers of individuals with severe mental illness | Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services | 54 (12), 33–38 | Australia | Study aimed to address the benefits to carers of several days relief from their caring responsibilities | Carers (n = 9) of a cohort of individuals with SMI who attended a therapeutic recreation initiative, Recovery Camp, were surveyed in late May 2015 | Qualitative study | A custom-designed instrument using open and closed questions was administered | Constant- comparative method (Strauss & Corbin,1990) |

* Caring Impact on health and well-being. * Caring Impacted on leisure Activities. * Benefits of respite. The research adds to the body of knowledge of the benefits of respite and the necessity for carers to engage with respite services. This study doesn't describe in detail the relationship between researchers and participants |

| 2 | Gillieatt et al. (2018) | Evaluation of a West Australian residential mental health respite service | Health and Social Care in the Community | 26 (3), e442–e450 | Australia | Study aimed to evaluate a pilot residential respite service |

Eight family members/carers and four consumers using the service, and five service providers Respite service in Western Australia |

Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke,2006) |

The research adds to the body of knowledge of the experience of respite from 3 different perspectives. Discussion revolves around the issues related to planning for respite, complex and unmet needs and the appropriateness of respite models. Overall, respite services for people with MI that is built upon the aged and disability services models do not ‘fit’ mental health. This study doesn't describe in detail the relationship between researchers and participants |

| 3 | Jardim and Pakenham (2009) | Pilot investigation of the effectiveness of respite care for carers of an adult with mental illness | Clinical Psychologist | 13 (3), 87–93 | Australia | Study involved a pilot investigation of the effectiveness of accessing respite care for carers of individuals with a mental illness |

Participants were 20 carers recruited through carer organisations; 10 carers who accessed respite and 10 carers who had never accessed respite recruited through support organisation |

Quantitative study | A pre- and post-respite assessment, and 3-month follow-up design. A total of 25 questionnaire packages | Non parametric test were used due to small sample size (Quantitative) |

This study reported respite care has results in a decrease of care burden. no differences between two groups but decrees objective burden and increase stress after respite care no changes for subjective burden, depression, anxiety, relation, life and health. The limitation the sample size is too small |

| 4 | Jardim and Pakenham (2010a) | Carers of adults with mental illness: Comparison of respite care users and non-users | Australian Psychologist | 45 (1), 50–58 | Australia | Study aimed to investigate the rate, type and duration of respite care use in carers of an adult with mental illness, and the differences between respite care users and non-users on demographic, caregiving context and adjustment variables |

106 carers of an adult with MI recruited through two carer support organisations in QLD. These agencies were—ARAFMI & Carers QLD |

Quantitative study | Survey questionnaire. |

Quantitative Chi-squared tests ANOVA MANOVA |

the study provides foundational data on respite care in mental health carers. Implications are that respite care services for mental health carers need to be varied, available for carers on a weekly-monthly basis with a range in duration but catering for higher use of 2 days respite periods. 16–18% of 106 participants indicated elevated levels of distress. The limitation of this study Participants were not ‘followed up |

| 5 | Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) | Carers' views on respite care for adults with mental disorders. Advances in Mental Health | Advances in Mental Health | 9, 84–97 | Australia | Study aimed to examine informal mental health carers' perceptions of respite care |

106 carers caring for an adult with mental illness recruited through carer support organisations |

Qualitative study | Carers provided written responses to open-ended questions covering four areas: barriers, positive and negative aspects, and improvements associated with respite care | Content analysis | The research adds to the body of knowledge with regard to understating the experience of respite care. As with other research—barriers were identified. Suggested improvements for respite care were also highlighted. This study doesn't describe in detail the relationship between |

| 6 | Jeon et al. (2006) | Give me a break’– Respite care for older carers of mentally ill persons | Journal of Caring Sciences | 20, 417–426 | Australia | Study aimed to explore older family carers' needs for, access to and use of respite services when caring for people with a mental illness (excluding dementia) in the community |

26 mental health professionals, 21 family carers aged over 55 years and 25 respite service providers The Eastern suburbs of Sydney |

Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Content analysis (Morse and Field) NUD*IST 6 |

The research adds to the body of knowledge of the experience of respite about * limited respite care utilisation*limited respite care availability, provision and flexibility and limited knowledge of respite care services. This study doesn't describe in detail the relationship between researchers and participants |

| 7 | Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh (2007) | Factors influencing the use and provision of respite care services for older families of people with a severe mental illness | International Journal of Mental Health | 16 (2), 96–107 | Australia | Study aimed to identify and examine the factors influencing the use and provision of respite services for older carers of people with a mental illness |

72 from older family carers, care recipient and mental health care professionals The Eastern suburbs of Sydney |

Qualitative study | Semi- structured, in-depth interviews, and structured self-completed questionnaires | Content analysis (Morse and Field) |

The research adds to the body of knowledge with regard to understanding the experience of respite care.—barriers were identified. A lengthy series of recommendations was identified. Limitation for this study The researcher has not overtly described their relationship to the participants |

2.3 Data Evaluation

The first author initially screened the studies by title or abstract, and then all research team members discussed the results until a consensus was reached. Next, the authors appraised all of the included papers individually, followed by a group discussion of the appraisal results.

The authors sought to enhance credibility by selecting valid, well-authenticated electronic databases and assessing the representativeness of each study included to ensure that these studies were relevant to the aim of the review. The studies selected for this review came from primary sources. Each of the study authors appraised the quality of evidence independently using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) framework (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2018). The CASP comprises a group of critical appraisal tools covering a wide range of research. The CASP provided a comprehensive checklist to assess the quality of methodology for each qualitative study. Using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) involved focusing on the rigour of the qualitative studies explored, the justification of study aims, sampling and recruitment strategies, data analysis strategies and the discussion in the study report. None of the qualitative studies described in detail the relationship between researchers and participants (Brighton et al. 2016; Gillieatt et al. 2018; Jardim and Pakenham 2010b; Jeon et al. 2006; Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

The quantitative studies were appraised using The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for quasi-experimental studies (Barker et al. 2024) and the JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies (The Joanna Briggs Institute 2017). The JBI review process is essentially an analysis of the available literature (i.e., evidence) and a judgement of the effectiveness or otherwise of a practice, involving a series of complex steps. JBI takes a particular view on what counts as evidence and the methods utilised to synthesise those different types of evidence. In line with this broader view of evidence, JBI has developed theories, methodologies and rigorous processes for the critical appraisal and synthesis of these diverse forms of evidence in order to aid in clinical decision-making in healthcare (Tufanaru et al. 2024).

In the Brighton et al. (2016) study, compelling evidence was found to support the favourable impact of respite care on the well-being of caregivers. The use of the CASP tool for critical appraisal affirmed the study's validity, reliability and applicability. The findings hold both statistical and clinical significance, offering valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners in the field of mental health services. Gillieatt et al. (2018) highlight that the benefits of respite services, including enhanced mental health and reduced stress, outweigh any potential drawbacks or costs. This study provides strong evidence to support the positive influence of residential respite services on both caregivers and care recipients. Employing the CASP tool for critical appraisal reaffirms the study's validity, reliability and applicability. The findings carry statistical significance and deliver valuable insights for the development and implementation of similar services in different regions.

The study by Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) provides valuable insight into respite care for adults with MI from the carers' perspective. The study discusses implications for practice, policy and future research, highlighting areas for improvement in respite care services. The study is valuable for informing practice and policy, contributing to the improvement of respite care services and support for carers.

The studies by Jeon et al. (2006) and Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh (2007) offer practical recommendations and significant insights to improve support and respite care services for older carers and families of people with severe MI. The researchers highlight the unique needs of this population and discuss implications for practice, policy and future research, all conducted with methodological rigour and ethical considerations. The findings are well-documented and offer significant insights into the provision and use of respite care services.

As indicated, the JBI checklist was used to assess validity and reliability of the quantitative studies by exploring whether the project addressed a clearly focused issue, the process of recruitment, if the authors identified all of the important confounding factors, the clarity of the study results and the implications of the study findings. The study by Jardim and Pakenham (2009) provides preliminary evidence on the effectiveness of respite care for carers of adults with MI, with significant findings on reduced burden but increased stress post-respite. The study is a valuable pilot investigation highlighting both potential benefits and risks associated with respite care for mental health carers. The use of rigorous methods and validated outcome measures (19-item Burden Assessment scale) enhances the reliability of the findings, although the small sample size and attrition limit the generalisability. Further research is recommended to explore these findings in larger and more diverse populations.

The study by Jardim and Pakenham (2010a) demonstrates clear definitions and detailed descriptions and employs valid and reliable measurements. Furthermore, the study is well-designed and provides valuable insights into the impact of respite care on carers of adults with MI. The use of standardised measurement tools and appropriate statistical methods (Relationship quality, 18-item inventory of caregiving tasks, burden assessment scale, 15-item SRGS, 21-item depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, DASS-21, satisfaction with life scale) strengthens the validity of the findings. The study meets the necessary criteria for inclusion, providing a strong analysis of the differences between respite care users and non-users among carers of adults with MI. No study was excluded based on this data evaluation (Whittemore and Knafl 2005).

Tables 3–5 illustrate the critical appraisal of articles using CASP for qualitative JBI checklist for quantitative studies.

| References | Title | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brighton et al. (2016) | The effect of respite services on carers of individuals with severe mental illness. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | Gillieatt et al. (2018) | Evaluation of a West Australian residential mental health respite service | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | N | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3 | Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) | Carers' views on respite care for adults with mental disorders. Advances in Mental Health | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | N | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 4 | Jeon et al. (2006) | Give me a break’– Respite care for older carers of mentally ill persons. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | C | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5 | Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh (2007) | Factors influencing the use and provision of respite care services for older families of people with a severe mental illness | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | C | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

- Abbreviations: C, can’t tell; N, no; Y, yes.

| References | Title | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Include study | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Jardim and Pakenham (2009) | Pilot investigation of the effectiveness of respite care for carers of an adult with mental illness. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

- Abbreviations: N, no; Y, yes.

| References | Title | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Include study | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Jardim and Pakenham (2010a) | Carers of adults with mental illness: Comparison of respite care users and non-users | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

- Abbreviation: Y, yes.

2.4 Data Analysis

The first author (CI) coded the results to extract the themes which were refined and developed with the research team via observing the emergence of the concepts and finding similarities. At the same time, the research team iteratively developed initial thoughts on key findings (Ingram et al. 2006). In the initial phase of analysis, the CI identified and defined all possible codes. Thereafter, the data was based on respective definitions under each code. Upon completion of the study, the coded data were used to identify similarities and differences. Finally, the researchers grouped similar data under the shared experience's theme.

3 Findings

3.1 Study Selection

Seven articles were included in this review. All were based on research conducted in Australia. Five studies used qualitative methodology, while the remaining two were quantitative. Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the studies included in the article and provides the findings for each individual study.

3.2 Synthesis of Findings

Four overarching themes were identified in terms of informal carers. Each theme incorporated sub-themes linked to emerging key concepts, which enabled the authors to distinguish the essence of meaning (Hewitt-Taylor 2017).

The identified themes are: (a) carers' relief of carer burden; (b) benefits for individuals with MI; (c) barriers to accessing respite care, including a discussion of the lack of suitable respite services, insufficient knowledge and understanding of respite care for carers, respite accessibility challenges accessible for people with MI, the reluctance of people with MI to go into respite care and increasing stress and anxiety for carers; and (d) inappropriate services model for respite care for individuals with MI. This theme incorporated a discussion on the knowledge deficit about MI, inappropriate activities and lack of awareness/ understanding of cultural and diverse needs (Table 6).

| No. | References | Titles | Themes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relief of carers burden | Benefits for consumers | Barriers to accessing respite | Inappropriate services model for respite care | |||||||||

| Lack of respite services | Insufficient knowledge and understanding of respite care | Lack of respite flexibility | Consumer reluctance to go into respite care | Respite accessibility challenges accessible for people with MI | Knowledge deficit about mental illness | Inappropriate activities | Lack of awareness/ understanding of cultural and diverse needs | |||||

| 1 | Brighton et al. (2016) | The effect of respite services on carers of individuals with severe mental illness. | * | |||||||||

| 2 | Gillieatt et al. (2018) | Evaluation of a West Australian residential mental health respite service | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| 3 | Jardim and Pakenham (2009) | Pilot investigation of the effectiveness of respite care for carers of an adult with mental illness. | * | * | * | |||||||

| 4 |

Jardim and Pakenham (2010a) |

Carers of adults with mental illness: Comparison of respite care users and non-users. |

* | * | * | |||||||

| 5 | Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) | Carers' views on respite care for adults with mental disorders. Advances in Mental Health | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

| 6 | Jeon et al. (2006) | Give me a break’– Respite care for older carers of mentally ill persons. | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| 7 | Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh (2007) | Factors influencing the use and provision of respite care services for older families of people with a severe mental illness | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

- Note: ‘*’ indicates the presence of the theme in the article.

3.3 Relief of Carer Burden

This overarching theme focused on the relief of the carer burden described in the primary studies related to informal carers' experiences when using respite care services.

Six out of the seven chosen papers explored the impact of utilising respite services by informal carers through the lens of a respite care relief carer burden (Brighton et al. 2016; Gillieatt et al. 2018; Jardim and Pakenham 2009, 2010a, 2010b; Jeon et al. 2006). According to the study findings, most of the informal carers experienced relief from burden during their use of respite care.

Carer burden has been defined as a ‘multidimensional response to the negative appraisal and perceived stress resulting from taking care of an ill individual’ (Kim et al. 2012, 846). In that light, a solution that relieves or alleviates carer burden could be expected to result in a positive perception of the experience on the part of the carer.

According to the studies analysed, the major impact of the use of respite care was the time it gave informal carers to participate in leisure activities, rest, socialise and cope better with difficulties in the long term, as well as feel more comfortable overall. For example, Jeon et al. (2006) explored the perceptions of older adults who served as family carers for people with MI who needed access to and use of respite services. In the study's semi-structured interviews, seven carers described their positive experiences in using respite care services in terms of having time to themselves.

Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) also identified a decrease in their objective burdens (including financial problems, limitation of personal activity, household disruptions, social disturbance) as a result of having time for themselves. This outcome meant that these carers could cope better with the tasks necessary to continue to care for their relatives.

Similarly, Brighton et al. (2016) examined the impact of enabling people with MI to attend Recovery Camp as a respite service that gave carers several days of relief from their caring responsibilities. All the carers who were interviewed confirmed that they experienced some benefits from this respite. They had time for themselves and spent this time engaging in pursuits such as shopping, going to the hairdresser, having a meal at a restaurant or simply engaging in leisure activities. Some of them also described using the break to look after their physical health, as one carer remembered, stating, ‘I've just had surgery on my spine, so my time was fully spent in resting my back. I have only been allowed to venture out to keep doctors' appointments for quite a while’ (Brighton et al. 2016, 37). In addition, Brighton et al. (2016) report that respite care allowed carers to spend time with each other as a couple, carers thought caring for people with MI had a negative effect on the relationship.

Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) offered similar findings. Their study, which examined 106 carers' perceptions of respite care, found that fewer than half (36%) of the participants had used respite care, while the majority (64%) had never accessed respite care. The study found that the carers who did experience this service used their respite time as an opportunity to relax and engage in activities that gave them pleasure. In short, they simply enjoyed taking a break from their caring role. Moreover, this respite enabled them to cope better when their caring role resumed.

A study by Gillieatt et al. (2018) involved family/carers, people with MI and service providers' experiences of respite service in Western Australia. According to the researchers' findings, six out of eight carers had a positive experience regarding the respite service. Specifically, carers described how they felt relaxed and that this was possible because the respite facility was an asylum (meaning a place of safety). One carer emphasised ‘feeling peace of mind that their loved one was safe’ (Gillieatt et al. 2018, e446). The authors concluded that a safe, calm environment and having staff available to help and support residents at all times can give carers peace of mind.

Similarly, Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) described how some carers felt that a safe environment with non-judgemental staff who are willing to try and engage with consumers is an essential aspect of using respite care.

It can be concluded, therefore, that services that offer respite care provide the necessary security for informal carers to place their family members in care. Furthermore, this peace of mind enables carers to perceive the respite experience positively.

3.4 Benefits for Individuals With MI

The second theme that carers in the selected studies described was the benefits for people with MI. Three out of the seven studies explored the impact of utilising respite services by informal carers through the lens of respite care benefits for individuals with MI (Gillieatt et al. 2018; Jardim and Pakenham 2010b; Jeon et al. 2006).

The first factor that emerged in our analysis was a sense of universality in that opportunities were provided for the people with MI to socialise with people who had a similar condition (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b; Jeon et al. 2006). People with MI were able to enjoy activities such as sports or playing cards or other games and further developed friendships (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b; Jeon et al. 2006). Gillieatt et al. (2018) found that people with MI in their study felt adequately cared for and supported during their respite experience. Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) and Jeon et al. (2006) also found that respite offered time for individuals with MI to practice independence and freedom by having a break from their families. Three studies, Gillieatt et al. (2018), Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) and Jeon et al. (2006), agreed that using respite care services was advantageous for people with MI in some perspectives.

3.5 Barriers to Accessing Respite Care

The third theme in this review was that not all carers' experiences of respite care were helpful. Six out of seven of the analysed papers revealed how respite care affected some carers adversely (Gillieatt et al. 2018; Jardim and Pakenham 2009, 2010a, 2010b; Jeon et al. 2006; Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

The carers who participated in the studies under consideration discussed many barriers to accessing respite care that created difficulties for them in terms of their ability to utilise services. A number of subthemes related to barriers emerged during our analysis, including lack of suitable respite services available for people with MI, insufficient knowledge and understanding about respite care services for carers, respite accessibility challenges accessible for people with MI, the reluctance of patients with MI to go into respite care and increased stress and anxiety on the part of carers during respite care.

3.5.1 Lack of Suitable Respite Services

Carers described the availability of respite care services, in general, as being limited, and at least one study reported that most of these services focused on care for older adults and/or people with physical disabilities (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). Jeon et al. (2006) also described a lack of respite services for people with mental health issues among government or non-government programmes and that the effort to focus more broadly on mental health in the Australian health care system was inadequate, which in turn has resulted in a lack of funding specifically assigned for respite care.

The relative difficulty in accessing services for people with MI compared to people with other disabilities and forms of dementia led carers to describe their negative feelings about this difficulty. In particular, carers believed that society, in general, and health care services, in particular, could not cope with people with MI due to a lack of knowledge about how to care for them (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). For example, among the participants in a study by Jardim and Pakenham (2010b), 47% of carers reported that the respite care that was available to them was not suitable. Among the quotations that the researchers included in their report were various observations that their participants made, such as, ‘There isn't any suitable respite … [the] few services that are around just don't offer what young adults with depression and anxiety want’ and ‘We do not have a respite situation in our city which would be suitable’ (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b, 92).

3.5.2 Insufficient Knowledge and Understanding of Respite Care for Carers

Carers consider a lack of knowledge and understanding of respite care a common barrier to utilising respite services. For some carers, the actual meaning of respite care was not clear (Jeon et al. 2006), while others defined respite care as a physical or mental break from the caring role. Carers also did not relate their need for a break to the use of respite services (Jeon et al. 2006). According to Jeon et al. (2006), carers also reported that they did not know what respite care services could offer them. The criteria for using respite was unclear for carers as well as health care professionals, and some carers believed that respite care was limited to care for older adults and/or people with dementia (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). Moreover, the timing for using respite services remained unclear for some carers, as they thought that respite was available only in times of crisis management or during emergencies (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

3.5.3 Respite Accessibility Challenges Accessible for People With MI

Our review and analysis revealed that entering respite care was restricted by the use of specific criteria such as the patient's health condition, diagnosis, geographical location, age, length of the caring role and ethnicity. All these restrictions had the potential to negatively impact access to respite care due to a lack of flexibility for carers to meet the demands that respite service providers levied (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

Respite rules and regulations that many services stipulated also had a negative impact on flexibility, such as the lack of freedom to undertake activities as desired by a patient with MI or, for example, restrictions on smoking (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b). Irregular and inflexible access to services was also considered a barrier for carers (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b). Although the carers considered respite care necessary, they found the inflexible timing associated with existing services frustrating (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). Planning for respite became a challenge for carers, who experienced long waiting times compared with the short time allowed for access (Gillieatt et al. 2018).

Jardim and Pakenham (2010a) reported a mean duration of respite in their study of 2 days. Such a short period is insufficient to impact the physical health and life satisfaction of either the carer or the people with MI, and along with the lack of flexibility, this limitation affects the use of respite services negatively.

3.5.4 Reluctance of People With MI to Go Into Respite Care

Respite care is a service for carers and people with MI, making it essential to provide a positive experience for both (Jeon et al. 2006; Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). The reluctance on the part of patients with MI towards using respite care is a significant barrier to accessing respite services. For example, Jardim and Pakenham (2010b) discovered that 74% of their participating carers indicated that people with MI had rejected respite opportunities. Reasons given included anxiety about changing their environment or daily routine, being afraid to venture outside the home, disagreeing with the view that they have an illness and a refutation of any need to use respite services. Furthermore, patients' rejection of respite care led to conflicts between carers and their relatives (Jeon et al. 2006). Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh (2007) found that carers decided not to use respite care or had a passive attitude toward it because they were concerned about their relative's health and well-being and worried about causing conflicts between them and their relative over the issue. According to these findings, reluctance expressed by patients with MI can hamper carers from utilising respite care.

3.5.5 Increasing Stress and Anxiety for Carers

This review revealed that while respite services offered a positive benefit related to the objective burden, the subjective burden (shame, stigma, guilt, resentment, grief, worry) remained unaffected. Regarding this aspect, carers reported experiencing an increased stress level (Jardim and Pakenham 2009). For example, some researchers observed elevated levels of depression (22%), anxiety (16%) and distress (28%) of 106 carers (Jardim and Pakenham 2010a). The quantitative studies were congruent with the results of the qualitative research, where participants expressed feelings of anxiety, guilt, stress and worry (Jardim and Pakenham 2010a). As a result, because of negative experiences, 15% of 106 carers who participated in one of the studies surveyed described their reluctance to utilise respite care due to poor past experiences and did not ask for help again from respite care services (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b). According to these findings, increased stress and anxiety for carers can create barriers to seeking respite care.

3.5.6 Inappropriate Service Model for Respite Care for Individuals With MI

The fourth theme in this review emerged to be the inappropriate service model for respite care for individuals with MI. Five out of seven of the analysed papers revealed how respite care affected some carers adversely (Gillieatt et al. 2018; Jardim and Pakenham 2010a, 2010b; Jeon et al. 2006; Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

Historically, respite care services were established in the older adult care and disability sectors but not specifically for the mental health sector; therefore, the needs of people with MI have not been met and remain mismatched with carers' expectations (Gillieatt et al. 2018). These inappropriate service models, in turn, have had an impact on staff, who were found to have insufficient skills to deal with people with MI, provided inappropriate activities and offered poor support related to reflecting the cultural diversity of patients with MI.

3.5.6.1 Knowledge Deficit About MI

This review revealed that carers viewed staff who worked in respite services as having insufficient skills to care for people with MI. Overall, the articles detail how carers view health professionals as unable to provide safe care for people with MI (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b; Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). For example, one carer specified that the ‘respite worker was not able to provide a sense of safety/care’ (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b, 92). Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh (2007) also described how staff had difficulty establishing rapport with carers, and sometimes, they provided information that lacked adequate explanation.

3.5.6.2 Inappropriate Activities

The studies examined how inappropriate service models for respite care impacted the activities provided. Carers and patients with MI in the studies under consideration described respite services as providing care for a variety of people simultaneously, including older adults, patients with disabilities and those with MI; moreover, the activities offered tended to be unsuitable for all participants (Gillieatt et al. 2018; Jardim and Pakenham 2010b). Among the participants described Jardim and Pakenham (2010b), 40% of people with MI encountered a lack of suitable activities.

3.5.6.2.1 Lack of Awareness/Understanding of Cultural and Diverse Needs

This review also uncovered a general lack of attention to cultural diversity because of the inappropriate service model for respite care. Some carers believed that language differences that appeared due to cultural diversity should be considered in the context of respite care, but they found attention in this area lacking (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). Thus, insufficient support from health care providers or other services such as, for example, translation services were missing (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

Carers' values and beliefs about caring and family tend to vary from one culture to another (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). A lack of cultural understanding among mental health workers and regarding Indigenous Australians has also raised a barrier to accessing respite care (Jeon et al. 2006; Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). Such factors impacted the carers' ability to place their trust in respite care services, leading them to be hesitant to use these services again. In this sensitive context, carers' dissatisfaction with the services they have tried can arise from a single negative experience (Gillieatt et al. 2018).

4 Discussion

This integrative literature review aimed to investigate empirical evidence about the experiences of those who care for people living with MI when using respite care services. This study represents the first review to examine the carers perspectives for people with MI since the study by Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson (2005). Such a scarcity of studies on this topic reflects the limited amount of research focusing on the lives of carers of people with MI. This study builds on the findings by Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson (2005) identifying similar positive and negative impacts of respite care services for carers. However, despite the ensuing years and the increased recognition of the need for respite care more broadly, significant issues remain to be addressed.

This integrative review highlighted the benefits that informal carers perceived from using respite care. Such services offered these individuals a break from caring when they felt their loved ones would receive adequate social and emotional support. These results are consistent with the previous review by Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson (2005), and also by Utz (2022) which also reported advantages and necessity of using respite care.

As indicated, the focus of research on respite care mainly concerns people living with dementia. Such studies consistently found that respite generated positive experiences for carers and people with dementia and decreased burden. For example, Vandepitte et al. (2016) identified properly structured care settings enable people with dementia to have increased autonomy and opportunity to socialise. O'Connell et al. (2012) found that people with dementia benefitted from respite care, and that respite services would be recommended to others. The same study noted that people with dementia experienced benefits from using respite care. Hence, all participants generally had high satisfaction levels from using respite care services.

Stirling, Dwan, and McKenzie's (2014) study of carers for people with dementia found that participants did not feel guilty that their relatives had used respite care services, that 80% of carers enjoyed the break, and 56% reported that people with dementia experienced increased social interactions. These results are similar to the findings of Mason et al. (2007) who conducted a systematic review to analyse evidence about respite care for older adults, including people with dementia and their carers. Mason et al. (2007) found many positive impacts of respite care services.

Similar to the findings of this current review, despite positive respite experiences of many people with dementia and their carers, there were also negative experiences. In a literature review by Neville et al. (2015) that examined respite care for people with dementia, negative outcomes included sleep disruptions, disorientation, exhaustion and changes in their routines while positive experiences included improved socialisation and the chance to have some time out of the house and away from family, improving self-esteem (Neville et al. 2015). Notably, however, the short period in which respite care has been utilised has increased the difficulty of assessing its effectiveness (Vandepitte et al. 2016).

Turning to people with MI, the studies reported in this current review found that barriers to accessing services and largely inappropriate service models resulted in negative experiences for carers. Lack of adequate respite time, long wait times for access and inflexible processes, such as the requirement to fill in many forms, were reported as reasons that carers did not use respite care (Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson 2005).

This integrative literature review identified that the negative aspects of utilising respite services included feeling guilty and increased anxiety and stress on the part of most carers. This finding is in line with those Neville et al. (2015) regarding the use of respite by carers of people with dementia, where the authors suggested that carers also experienced feelings of emotional devastation, guilt and despondency because of perceptions of abandoning their relative with dementia and failing in their family duty.

Researchers clearly documented the need for carers to have qualified staff working in respite care services. Jeon, Brodaty, and Chesterson (2005) reported on this issue nearly two decades ago. A study that explored carers' perspectives of respite care O'Connell et al. (2012) identified carers' concerns about the quality of care provided, including inadequate staff, limited programmes and rigid communication among staff and carers. Such negative experiences were enough to cause carers to refuse to utilise such services again. Neville et al. (2015), reported that respite services could not adequately support culturally and linguistically diverse clients. This finding is in contrast with descriptions provided by Stirling, Dwan, and McKenzie (2014), who found that carers reported staff as being kind and willing to care and said that they experienced effective communication. Thus, the findings of the current review confirm the importance of supporting carers and improving respite services to encourage carers to utilise them.

4.1 Suggestions and Recommendations

- Encourage carers to increase their access to respite care by empowering them to explore their needs, educating them about MI and involving them in decision-making (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

- Increase the awareness and acceptance of the need for respite care by carers of people with MI.

- Encourage respite care providers to seek more government funding and collaborate with other services to enhance the quality of their services (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

- Re-conceptualise respite care by placing it centrally as a critical part of mental health services and including it in discharge planning and rehabilitation programmes (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

- Improve the quality of services by providing suitable and enjoyable activities appropriate to different ages, genders and mental and physical conditions (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b).

- Allocate time for therapy and assistance within routine activities (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

- Improve services by enhancing staff competence (Jardim and Pakenham 2010b). This goal can be achieved by providing regular education about caring and effective communication strategies in dealing with people with MI. This approach would involve teaching staff about psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery and learning how to build trust and rapport with carers and patients (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007).

- Help carers identify the best time and appropriate amount of time for them to utilise respite services (Jeon, Chenoweth, and McIntosh 2007). Encourage carers to use respite frequently and at regular times to improve relations between carers and relatives and staff (Jardim and Pakenham 2009).

4.2 Limitations

The strength of this review is its specific focus on the experience of those who care for individuals living with MI regarding the use of respite care services. All reviewers independently appraised all the studies reviewed.

Limited evidence was found that focused specifically on the experiences of carers for people with MI during their use of respite care. The lack of attention to this population in terms of the study topic in this field impacted the number of articles; moreover, some studies may have been missed. Assistance from a qualified university librarian was sought to mitigate this limitation. The librarian also responded with a small group of returned results. The lack of existing evidence uncovered in this review, therefore, demonstrates a gap in the research.

An interesting result was all of the studies that emerged during the search process were conducted in Australia, which could be argued as a limitation given the homogeneity of the geographical setting.

5 Conclusion

This review identified a distinct shortage of research exploring the use of respite care by those who care for people with MI. Although the findings revealed that respite was essential to relieve the burden of care, both positive and negative experiences arose from the utilities of respite care. On the positive side, utilising respite care services can reduce the caregiver's workload and have a positive impact on both caregivers and individuals with MI. However, respite care can also lead to an increase in caregiver stress levels due to the lack of available services and a lack of understanding and knowledge about respite care services. Carer experiences were thought to affect the use of respite and the impact was felt by both carers and care recipients. Respite is known to yield benefits and ease carer fatigue but only it is perceived as appropriate if the model of care is fit for purpose. Notably, the study findings yielded helpful suggestions for improving respite care and increasing respite service for this important cohort in the future.

6 Implications for Mental Health Nursing Practice

Mental Health Nursing is a comprehensive and patient-centred practice that involves working closely with both consumers and carers. To ensure a recovery-oriented approach that is inclusive of all stakeholders involved in a person's journey to recovery, it is paramount to have a deep understanding of the needs of carers of individuals with MI. Such an understanding will help improve the quality of care provided and foster better relationships with the carers involved.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission and Imam Abdulrahman University in Saudi Arabia. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Wollongong, as part of the Wiley - University of Wollongong agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.