Factors Influencing Staff Perceptions of Inpatient Psychiatric Hospitals: A Meta-Review of the Literature

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals ultimately impact a range of organisational and care-related variables, including staff retention and quality of care for inpatients. The aim of this study was to conduct a meta-review to synthesise themes reported by staff to influence their perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews. PsycINFO, CINAHL, MEDLINE and EMBASE were systematically searched. Reviews were eligible for inclusion if they examined the perception/experience of paid staff involved in caring for adults with mental illnesses admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital. Eligible reviews were assessed for methodological quality and bias. Thematic synthesis was used to merge thematically similar findings into an aggregate summary. Fifteen reviews were included, from which seven themes were reliably extracted: staff and patient safety, views on inpatients' experiences, relationships on the ward, ward rules, knowledge and experience, service delivery issues and coercive measures. Confidence in the evidence underlying each theme was analysed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation—Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) criteria. Results indicate that staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals overlap with inpatients' perspectives, particularly regarding the therapeutic relationship, coercive measures and ward safety, in addition to unique experiences. Factors identified can help guide ways to improve staff retention, satisfaction and quality of treatment.

1 Introduction

Staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals impact staff-related and organisational decision-making processes (De Benedictis et al. 2011; Laker et al. 2020), job satisfaction (Scanlan, Devine, and Watkins 2021; Van Bogaert et al. 2013), staff burnout rates (Laker et al. 2012, 2020; Van Bogaert et al. 2013), staff retention (Van Bogaert et al. 2013), the effectiveness of training and/or interventions (Botega et al. 2007; De Benedictis et al. 2011), quality of care (Van Bogaert et al. 2013) and patient1 outcomes (Joseph, Plummer, and Cross 2022). Moreover, staff perceptions influence how care is provided for patients (Awenat et al. 2017; De Benedictis et al. 2011; Rytterström et al. 2020). For instance, staff perceptions and beliefs about suicidality have been reported to influence the degree to which staff are willing to engage with and treat suicidal patients (Awenat et al. 2017). Furthermore, consider the high postdischarge suicide rates in inpatient psychiatric hospitals internationally (Forte et al. 2019; Haglund et al. 2019; Madsen et al. 2020; Walsh et al. 2015), which stand at up to 44 times the global suicide rate and do not appear to be a mere function of acuity of clinical presentation alone (Chung et al. 2017). Given this context, it is vital to understand the factors influencing staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals.

Before the move to deinstitutionalisation, with its consequent emphasis on community care from the late 20th century onwards, staff in inpatient psychiatric hospitals largely consisted of nurse attendants (Vrklevski, Eljiz, and Greenfield 2017). Internationally, the largest group within the inpatient psychiatric hospital workforce is still nurses (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2022; Jones 2006), making up 44% of the total mental healthcare workforce (Søvold et al. 2021). However, it is worth noting that psychiatric nursing staff are not a monolithic group. International standards of qualification and training of psychiatric nurses vary widely. For example, UK psychiatric nurses are specialised in mental health care without training in physical health care, whereas in Australia and New Zealand a psychiatric nurse's education is based on a generic nursing curriculum that only includes a limited amount of mental health specific knowledge and skills (McIntosh and Gournay 2017; Walker and McAndrew 2015).

Deinstitutionalisation further diversified workforce characteristics and staff work practices within inpatient psychiatric hospitals (Vrklevski, Eljiz, and Greenfield 2017). That is, in contemporary inpatient psychiatric hospitals, the workforce typically consists of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs). The term MDT broadly refers to a team of staff, commonly led by a psychiatrist, including members of different disciplines, such as social workers, psychologists and peer workers, who work in combination to provide comprehensive patient care (Burke et al. 2000; Jones 2006; Mitchell, Tieman, and Shelby-James 2008). However, in practice, the distinction between occupational roles is often blurred, with considerable overlap and even competition between role functions and duties, particularly for the delivery of care and treatment in inpatient psychiatric hospitals (Jones 2006; Maddock 2015; Vrklevski, Eljiz, and Greenfield 2017). As such, staff's self-reported perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals are both complex and varied.

Clarifying the factors that influence staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals is necessary for determining where resources can be most effectively targeted and policy changes and/or interventions implemented to retain well-trained staff, reduce turnover, enhance care and provision of training of new staff, and improve patient care and outcomes both during inpatient stays and postdischarge. Previous work has identified the factors (themes) that influence inpatients' perceptions of psychiatric hospitals, including relationships on the ward, the ward environment, coercive measures, legal status, autonomy, feeling deserving of care and expectations of care at admission and discharge (Modini, Burton, and Abbott 2021). However, there is a need to identify staff perceptions and assess whether inpatient and staff perceptions align.

Furthermore, though various reviews have been published examining factors that influence staff perceptions of working in inpatient psychiatric hospitals, these reviews typically only focus on a particular subset of factors. For instance, research may focus on select classes of staff (e.g., psychiatric nurses; Delaney and Johnson 2014), specific patient presentations (e.g., borderline personality disorder; Westwood and Baker 2010), patient populations (e.g., women; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021), treatment issues (e.g., self-injury; Bosman and van Meijel 2008) or workplace practices (e.g., use of seclusion and/or restraint; Al-Maraira and Hayajneh 2019). As far as has been possible to determine, no published review, meta-analysis or meta-review has yet sought to provide a comprehensive overview of all the factors that influence staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals.

Given the variety of systematic reviews and other reviews that have previously focused on a subset of the factors that influence staff perception of inpatient psychiatric hospitals, a meta-review is the most relevant and efficient method available to systematically collate the available research and provide a comprehensive synthesis of these factors. A meta-review is a review of reviews and is sometimes called an umbrella review (Aromataris et al. 2020). A meta-review provides a comprehensive, systematic summary and synthesis of the best available evidence from already available reviews on a topic of interest (Aromataris et al. 2020). For this research, the critical advantage of utilising a meta-review method is that it allows researchers to answer a broader question than any of the individual reviews included in the meta-review might have set out to address (Booth 2016).

A meta-review of staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals provides insight into the day-to-day running of inpatient wards and determines the degree to which staff and inpatient perceptions correspond. Therefore, the main aim of this research is to systematically identify, summarise and synthesise evidence from reviews and meta-analyses investigating the factors staff report that influence their perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals via a meta-review. We hope that the findings of this meta-review will assist in identifying areas for improvement and highlight already established beneficial workplace practices in inpatient psychiatric hospitals.

2 Method

2.1 Protocol, Registration and Reporting Structure

The meta-review was registered with the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews in October 2021: CRD42021260221. It followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA; Page et al. 2021) and reporting guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

2.2 Scoping Search

Before the meta-review, a scoping search was conducted using Google Scholar to map out the extent and nature of previous studies. Studies were initially examined for key themes without quality checking or full descriptions of their results. The results of the scoping search were used to determine whether a systematic review, meta-analysis or meta-review would be the most appropriate format for the main review, prior to designing search and eligibility criteria.

2.3 Search Strategies

Guided by the results of the scoping search, a search was conducted of the academic databases PsycInfo, MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL from inception to October 2022 for reviews and meta-analyses examining factors that influence staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals. The literature search was confined to a search of academic databases because a broader search would have involved contacting multiple local health districts, which was not feasible and would limit generalisability to an international context. Search strategies were tailored to each database using a combination of keywords and subject headings, such as ‘Health Personnel’, ‘Psychiatric Hospital’, ‘Perception’ and ‘Systematic Review’. Individual database search strategies are listed in Appendix A.

2.4 Eligibility Criteria

2.4.1 Reviews Were Included if They

- Examined the perception/experience of paid staff involved in the care of adults with mental illnesses admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital, and;

- Were a peer-reviewed systematic review, integrative review, rapid review, meta-analysis, meta-synthesis or literature review, and;

- Were written in the English language.

2.4.2 Reviews Were Excluded if

- They only examined children's, adolescents', ‘young persons'’, adult inpatients', service users', carers' and/or family members' perceptions of an inpatient psychiatric hospital, or;

- The setting was predominantly a correctional/prison hospital or focused on the care of inpatients with intellectual developmental disorders, or;

- They were a meta-review/umbrella review, conference presentation or a review of the psychometric properties of quality measures, or;

- They involved a narrative review based solely on the logic of configuration (i.e., a synthesis exceeding any specific findings of primary studies, merging thematically diverse findings into a model or theory) as the findings of such reviews cannot be de-configured and subsequently analysed at the level of primary studies (Petrovskaya, Lau, and Antonio 2019) as this review aimed to do, or;

- They only contained author opinion/commentary, or;

- Staff members' perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals were insufficiently differentiated from others' perceptions.

Where reviews contained perceptions of both staff and others in an inpatient psychiatric hospital, only data regarding staff experiences were extracted.

2.5 Review Selection

Following deduplication, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two authors (K.A.T. and M.M.) using the eligibility criteria and cross-checked for agreement before full-text articles were obtained. Full-text reviews were then independently assessed for inclusion in the meta-review (K.A.T. and M.M.). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion between raters.

2.6 Data Extraction

The data extraction form was created using Excel (version 2209). This form was pretested by author K.A.T. using data collected from three included reviews and used to correct any problems/issues with the form. The same author then used the revised form to extract data from all reviews, including citation details, review type (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods), quality rating, key aims, relevant findings, extracted factors/themes and the primary studies related to each extracted factor (Table 2). Only factors that staff reported affected their perception of inpatient psychiatric hospitals were extracted. Subsequently, a second author (M.M.) conducted a quality check of ~10% of the extracted data. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus.

When conducting a meta-review, it is important to consider the degree of potential duplication of extracted data where multiple studies of the included reviews have analysed data from the same primary studies (Petrovskaya, Lau, and Antonio 2019). Therefore, to minimise bias introduced by overlapping studies, the data extraction table listed the primary studies referenced in each included review for each extracted factor, allowing for the subsequent removal of duplicate studies. This approach aimed to neither overestimate nor underestimate the degree of overlap between studies, that is neither counting evidence twice and thereby magnifying its relevance nor excluding evidence from reviews that included the same primary studies but that extracted nonoverlapping data from those primary studies (Petrovskaya, Lau, and Antonio 2019). Where it was unclear whether the data were overlapping, a conservative approach was used in which it was assumed that there was overlap, and the duplicate study was removed.

2.7 Quality and Risk of Bias Assessments

The quality of all included reviews was independently evaluated using the AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al. 2017) appraisal tool (K.A.T. and M.M.). The AMSTAR 2 is a validated tool for assessing the quality of systematic reviews, including randomised and nonrandomised studies of healthcare interventions. As many of the included reviews analysed qualitative data, a few changes were made to the AMSTAR 2 items using peer-reviewed guidelines from the Joanna Briggs Institute (2017) critical appraisal checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses. It is noted that the AMSTAR 2 is regarded as validly modifiable as appropriate (Shea et al. 2017). Disagreements between evaluators were resolved through discussion.

For this meta-review, Items 1 and 7 were amended, as described in Modini, Burton, and Abbott (2021). Item 7 asks if ‘the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify exclusion’. It was amended to ‘Did the authors provide a tally, with explanations given, of full-text studies excluded?’. This was to align with the PRISMA guidelines used in this review, which do not specify the need for a list of excluded studies. Changes were also made to Item 8. Item 8 in its original form focuses largely on intervention outcomes. Therefore, Item 8 was amended to reflect the largely qualitative nature of the reviews in this meta-review: It was amended to include criteria for assessing whether included qualitative noninterventive studies were described in adequate detail; that is, a determination of ‘partial yes’ considered or at least described the risk of bias in the method, results or discussion; and a ‘yes’ also assessed risk of bias using a validated tool or, in the case of older studies, reviewed findings with peers and/or field experts.

In line with its author's recommendations for the use of the AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al. 2017), an overall confidence rating was made for each included review: high (no or one noncritical weakness); moderate (one or more noncritical weakness); low (one critical flaw with or without noncritical weaknesses); critically low (more than one critical flaw with or without noncritical weaknesses). Reviews determined to be ‘critically low’ were excluded from the meta-review to enhance confidence in the findings of the meta-review (Abdalrahim 2013; Al-Maraira and Hayajneh 2019; Bosman and van Meijel 2008; Jansen, Dassen, and Groot Jebbink 2005; Johnson 2004; Lelliott and Quirk 2004; Loukidou, Ioannidi, and Kalokerinou-Anagnostopoulou 2010; Moreno-Poyato et al. 2016, 2021; Morse et al. 2012; Odes et al. 2021; Papoulias et al. 2014; Paris and Hoge 2010; Sailas and Wahlbeck 2005; Stevenson and Taylor 2020; Stewart et al. 2009; van der Merwe et al. 2009, 2013; Wynn 2018). There was total agreement between evaluators on the reviews to be included in the meta-review.

Additionally, following Petrovskaya, Lau, and Antonio's (2019) umbrella review protocol, modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation—Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual; Lewin et al. 2015) criteria were applied at the level of individual findings to examine the confidence in the evidence in each extracted theme for qualitative data (Colvin et al. 2018; Lewin, Bohren, et al. 2018; Lewin, Booth, et al. 2018; Munthe-Kaas et al. 2018; Glenton et al. 2018; Noyes et al. 2018). Confidence was assessed with respect to this meta-review's aims rather than the included reviews' aims. A ‘middle ground’ decision rule was decided upon by the authors before the analysis (i.e., after reviewing the confidence ratings given to each factor, the final confidence rating represented an overall judgement of confidence rather than just the lowest or highest rating given to any single factor). This decision rule was used to make overall judgements about the confidence level of each theme in line with suggestions made in the CERQual guidelines (Lewin, Bohren, et al. 2018). Confidence was judged with regards to the three CERQual criteria thus far validated for use with meta-reviews: coherence (inappropriate oversimplification of data), adequacy (data richness) and methodological limitations (appropriate assessment of the risk of bias) (Lewin, Bohren, et al. 2018). The results of this appraisal are outlined in Table 1.

| Theme | Number of studies contributing to the extracted theme after deduplication | GRADE-CERQual confidence descriptora | Explanation of confidence assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety | 84 | Moderate | Minor–moderate concerns about coherence across all reviews. Minor–moderate concerns about methodological limitations in 4/11 reviews. Moderate concerns about adequacy in 3/11 reviews. |

| Views on inpatients' experiences | 14 | Moderate | Minor–moderate coherency concerns in all 3 reviews. Moderate methodological concerns in 1/3 reviews. Minor concerns about adequacy in 1/3 reviews. |

| Relationships on the ward | 90 | Low | Minor–moderate concerns about coherence across all 10 reviews. Moderate concerns about methodological limitations in 5/10 reviews. Moderate concerns about adequacy in 3/10 included reviews. |

| Ward rules | 31 | Low | Minor–moderate concerns about coherence in all 10 reviews. Minor–moderate concerns about adequacy in 7/10 reviews. Moderate concerns about methodology in 3/10 reviews. |

| Knowledge and experience | 26 | Low | Minor—moderate concerns about coherence across all 9 reviews. Moderate concerns about methodological limitations in 5/9 reviews. Moderate concerns about adequacy in 3/9 of the included reviews. |

| Service delivery issues (e.g., staffing levels, policies, resourcing) | 38 | Low | Minor–moderate concerns about coherence across all 5b reviews. Moderate concerns about methodological limitations in 3/5 reviews. Moderate concerns about adequacy in 2/5 reviews. |

| Coercive measures | 138 | Very low | Minor–moderate concerns about coherence across all eight reviews. Moderate concerns about adequacy in 4/8 reviews. Moderate concerns about methodological limitations in 4/8 reviews. |

- a Moderate confidence = extracted theme is likely to be a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest; low = theme is possibly a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest; very low = unclear if the theme is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest (Lewin, Booth, et al. 2018).

- b Data from the sixth review contributing to this theme (Richards et al. 2006) were not included here as they only formed part of the descriptive rather than thematic synthesis.

2.8 Data Synthesis

- Data describing staff perspectives and experiences of inpatient psychiatric hospitals were coded using Excel. A coding frame was created, guided by key themes identified in the scoping review and consisting of codes derived from a line-by-line examination of the synthesised data in the included reviews (Thomas and Harden 2008). Coding was performed by the first reviewer (K.A.T.).

- Codes were grouped into descriptive themes that captured and described similarities/categories in the data across studies (Thomas and Harden 2008). The descriptive form of these themes allowed for data from all included reviews, no matter the study design, to be pooled and summarised (as per Modini, Burton, and Abbott 2021).

- Data were synthesised across reviews, and analytical themes were developed and contextualised with reference to the meta-review's aims, leading to a final set of extracted themes or evidence findings (Table 2). Thematic extraction was judged complete at the point of data saturation. That is, when no new theme was being identified in the included reviews when compared to the already extracted themes (Fusch and Ness 2015; Saunders et al. 2018). As pointed out by Fusch and Ness (2015), failure to reach data saturation negatively affects the quality and validity of the resulting data synthesis.

- A second author (M.M.) independently conducted a reliability analysis to ensure all extracted themes could be inferred from the included studies.

- Confidence in the evidence from the thematic synthesis was assessed (Table 1).

| Author(s) | Year | Review type | Number of included studies | Quality rating | Relevant aim(s)a | Key finding(s)b | Extracted factor/theme(s)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander & Bowers | 2004 | Literature review: Included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. | 37 | Low | Investigate the relationship between flexibility/inflexibility of ward nursing rules and consumer outcomes in adult inpatient psychiatric wards. | Despite considerable heterogeneity in the findings of the included studies, the authors identified four main factors influencing nurses' perceptions: Job satisfaction, perceived control, attitudes and moral judgements of patient (mis)behaviours, and ward conflict management strategies. |

Coercive measures Knowledge and experience Relationships on the ward Safety Ward rules |

| Delaney & Johnson | 2014 | Meta-synthesis: Included only qualitative studies. | 16 | Low | Learn how inpatient psychiatric nurses depict their work with patients. | Seven themes were identified relating to psychiatric nurses' experiences in inpatient wards: Patient engagement, maintaining safety, patient education, nurses' attitudes to rules, nurses' self-directedness, role complexity and role difficulties. |

Coercive measures Knowledge and experience Relationships on the ward Safety Service delivery issues Ward rules Views on inpatients' experiences |

| Doedens et al. | 2020 | Systematic review: Included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. | 84 | Moderate | Summarise nurses' attitudes towards coercive measures and examine the influence of staff characteristics on the use of coercive measures in acute mental health inpatient settings. | The authors identified two key themes regarding nurses' attitudes towards coercive measures:

|

Coercive measures Knowledge and experience Safety Service delivery issues |

| Fletcher et al. | 2021 | Integrative review: Included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. | 30 | Low | Compare staff's and patients' perspectives on the causes of aggression and violence in inpatient environments. | Staff reportedly perceived the causes of aggressive/violent incidents related to five factors: Staffing, policies, resourcing, patient diagnosis and personality factors, and poor interpersonal skills. Both staff and patients perceived therapeutic relationships were protective against aggression. Authors concluded that the key factor differentiating between aggressive/violent outcomes or a resolution of an incident was staff use of patient-centred communication skills. |

Relationships on the ward Safety Ward rules |

| Gee et al. | 2017 | Rapid realist review: Included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. | 51 | High | Identify what factors enable, or inhibit, lasting change when multidisciplinary teams working in an adult mental health inpatient rehabilitative setting participate in a work-based training programme aimed at increasing their engagement with recovery-oriented practice. | Recovery-oriented training programmes significantly increased staff perceptions of factors including patient ‘input into care alters their treatment’, the amount of time staff spent directly engaging consumers, positive postdischarge prognoses, staff autonomy and evidence-based practice. | Knowledge and experience |

| Hallett et al. | 2014 | Systematic review: Included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. | 37 | Low | Identify psychiatric staffs' perceptions of the prevention of adult inpatient violence and aggression with a particular focus on primary and secondary measures. |

Staff perceived that violence in inpatient psychiatric wards could be prevented by a range of staff-related, organisational/environmental and patient-related factors. Staff perceptions of the preventability of violence varied, which the Authors suggested might influence staffs' choice of intervention. |

Relationships on the ward Safety Service delivery issues Ward rules |

| Jackson et al. | 2018 | Systematic review: Included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies as well as expert opinion articles. | 12 | Low | Explore what factors influence the decision-making of mental health professionals working in inpatient settings when releasing a consumer from seclusion. | Authors described four factors related to staff's decision to release patients from seclusion: Safety, external influences, patient compliance and release/reflection. Seclusion reduction programmes did not reduce the frequency of seclusion use compared to alternative practices, and staff remained universally approving of it, if more critical. |

Coercive measures Knowledge and experience Relationships on the ward Safety Service delivery issues |

| Laukkanen et al. | 2019 | Integrative review: Included quantitative and mixed methods studies. | 24 | Moderate | Synthesise psychiatric nursing staffs' attitudes towards containment methods in inpatient psychiatric care. | Overall, the authors found variability in nursing staff's attitudes to containment measures, with some evidence suggesting this may be a function of how much experience staff had implementing coercive practices, staff gender and age. |

Coercive measures Knowledge and experience Safety Views on inpatients' experiences Ward rules |

| Muir-Cochrane & Oster | 2021 | Qualitative synthesis review: Included qualitative studies. | 17 | Low | Synthesise and review staff's experiences of chemical restraint in adult mental health settings. | Staff reportedly regarded chemical restraint as justified in response to challenging behaviours and appropriate with respect to service delivery constraints, though sometimes violent in practice and resulting from lack of training in other risk management strategies. There was reported heterogeneity in staffs' perceptions of outcomes of chemical-restraint use for patients. Physicians and security guards were reported to experience a lack of choice in using chemical restraint due to needing to manage ward safety with physicians regarding it as a ‘last resort’. |

Coercive measures Knowledge and experience Relationships on the ward Safety Views on inpatients' experiences Ward rules |

| Nelstrop et al. | 2006 | Systematic review: Included qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. | 36 | Moderate | Assess staff perspectives on physical intervention and seclusion as interventions for the short-term management of disturbed/violent behaviours in inpatient psychiatric settings. | Staff were reported to have more favourable attitudes towards coercive measures than patients. Nurses were reported to adopt a more authoritarian approach to the use of coercive measures because of a perceived need to justify their actions. Nurses preferred seclusion over physical restraint, though acknowledged it was open to possible abuse. |

Coercive measures Ward rules |

| Richards et al. | 2006 | Systematic review: Included quantitative and mixed methods studies. | 34 | Moderate | Review the literature on the prevalence of indicators of low staff morale in acute inpatient mental healthcare staff. | Authors stated there was too much heterogeneity across primary studies to meta-analyse or support the idea that staff on acute and other inpatient wards experience very high levels of burnout, stress and low morale. | N/A. Descriptive synthesis only—no relevant qualitative data reported. |

| Scholes et al. | 2021 | Systematic review: Included qualitative and mixed methods studies. | 18 | oderate | Synthesise staff experiences of providing care to female patients in inpatient mental health services. | Nurses were reported to emphasise the buffering role of teamwork and professional supervision and the importance of attachment and trust for the therapeutic relationship. Occupational therapists were noted to highlight the need for female patients to have access to female staff. Under-resourcing decreased staff's sense of safety on the ward, as did the greater severity of self-harming behaviours and likelihood of assault in women's wards. |

Relationships on the ward Safety Ward rules |

| Westwood & Baker | 2010 | Literature review: Included qualitative and quantitative studies. | 8 | Low | Synthesise the literature on registered mental health nurses' attitudes towards patients in acute mental health inpatient settings with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and to identify if views held by nursing staff influence their practice and treatment of this patient group. |

Nurses were largely reported to have negative views of patients with BPD and distance themselves from these patients. Nurses were reported to perceive patients with BPD as inauthentic and manipulative and to feel devalued and used by them. However, some nurses were described as more optimistic in their views of patients with BPD because they were starting to believe BPD was treatable, providing nurses with hope for recovery. |

Relationships on the ward |

| Wilson et al. | 2021 | Integrative review: Included qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies. | 10 | Low | Explore mental health nurses' attitudes and experiences of trauma-informed care in adult inpatient mental health units. | Nurses were reported to sometimes experience the ward as (re)traumatising. Trauma-informed care training was noted to increase nurses' sense of confidence, therapeutic engagement, intention to change work practices and empathy/reflective capacity about the impact of childhood trauma on patients. However, nurses perceived several competing demands in their role, including a mismatch between trauma-informed, person-centred care and hospitals' task-based, efficiency-focused approach. |

Knowledge and experience Relationships on the ward Safety Ward rules |

| Wyder et al. | 2017 | Systematic narrative synthesis: Included qualitative and quantitative studies. | 21 | Low | Explore nursing staff's experiences of delivering care in acute inpatient units. | Nurses were noted to emphasise the role of person-centred care, teamwork and strong leadership in their work and find it challenging to balance restrictive practices with patients' rights. Nurses reportedly perceived teamwork was negatively impacted by competing understandings of care between different staff disciplines. |

Coercive measures Knowledge and experience Relationships on the ward Safety Service delivery issues Ward rules |

- a Only aims pertinent to staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals are reported.

- b Key findings = Findings reported in included reviews, which are relevant to the aims of this meta-review.

- c Extracted factor/theme(s) = Theme(s) identified via narrative synthesis of the reviews included in this meta-review.

There were insufficient data to conduct statistical meta-analyses. Therefore, quantitative findings from the included reviews were descriptively synthesised and integrated into the results of the thematic synthesis. One review (Gee et al. 2017) also included theory building following data extraction. In keeping with the logic of aggregation used in this meta-review, data were extracted only from the presynthesised summary of findings reported by Gee et al. (2017), which could be analysed at the level of primary studies.

3 Results

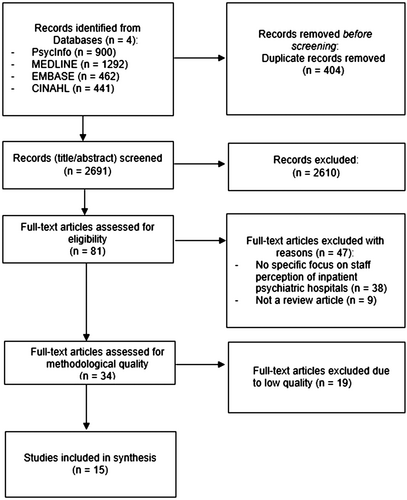

The systematic database search identified 3095 manuscripts. Following the deduplication and screening of these manuscripts, 34 reviews were eligible for inclusion. Of these, 19 were deemed ‘critically low’ in methodological quality using the AMSTAR-2 and excluded. No similar meta-reviews were found. Most reviews that were excluded because of methodological quality did not adequately analyse the risk of bias or provide summary explanations of included studies in their review. This resulted in 15 reviews being included in this meta-review (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Doedens et al. 2020; Fletcher et al. 2021; Gee et al. 2017; Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Laukkanen et al. 2019; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Nelstrop et al. 2006; Richards et al. 2006; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021; Westwood and Baker 2010; Wilson et al. 2021; Wyder et al. 2017). The review selection process is outlined in Figure 1.

Unfortunately, analysis of a ‘cohort effect’ (change over time) in staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals could not be investigated though it had been an aim listed in the preregistration protocol. This was because, with one exception (Doedens et al. 2020), the reviews included in this meta-review did not contain sufficient relevant detail to support a cohort effect analysis.

Table 2 summarises the 15 included reviews, including key results. Seven factors influencing staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals were extracted: staff and patient safety, views on inpatients' experiences, relationships on the ward, ward rules, knowledge and experience, service delivery issues and coercive measures.

3.1 Staff and Patient Safety

Eleven reviews examined the role of ward safety in influencing staff perceptions of inpatient hospitals (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Doedens et al. 2020; Fletcher et al. 2021; Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Laukkanen et al. 2019; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021; Wilson et al. 2021; Wyder et al. 2017). Overall confidence in this evidence was moderate (Table 1).

Nurses were reported to agree that establishing ward safety was a core aspect of psychiatric nursing (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Wyder et al. 2017) and a duty/responsibility (Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018) that took precedence over their caring role when faced with patient violence (Fletcher et al. 2021). However, there was reported heterogeneity within nursing staffs' use of violence prevention strategies, with some relying solely on restraint (Laukkanen et al. 2019) and others endorsing debriefing, training, enhanced staff–patient and staff–staff interaction, increased staffing and addressing lack of patient privacy and overcrowding (Fletcher et al. 2021).

Nurses were reported to think they needed to remain vigilant of risk on the ward (Delaney and Johnson 2014; Fletcher et al. 2021) and felt overloaded by a hostile work environment (Fletcher et al. 2021). Nurses' perceptions of ward safety were reportedly positively influenced by trauma-informed practices (Wilson et al. 2021), limit setting (Alexander and Bowers 2004), increased autonomy in decision-making, consultation with colleagues, effective crisis management (Delaney and Johnson 2014), training, knowledge of patient history, pro-active de-escalation techniques (Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014) and patient engagement (Wyder et al. 2017). Factors that were noted to decrease staff perceptions of safety included under-resourcing (Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021), relocating from a ‘mental institution’ to a general hospital setting (Alexander and Bowers 2004), being the victim/witness of patient assault (Doedens et al. 2020) and the relatively greater severity of self-harming behaviours and likelihood of assault in women's-only wards (Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021).

3.2 Views on Inpatients' Experiences

Three reviews described staff perceptions of inpatients' experiences on the ward (Delaney and Johnson 2014; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Laukkanen et al. 2019). Overall confidence in this evidence was low (Table 1).

Nurses were reported to believe that the therapeutic relationship positively impacted patient and staff perceptions of ward life and increased patient empowerment (Delaney and Johnson 2014). There was some heterogeneity in staff perceptions of inpatients' experiences of coercive measures, though staff largely thought patients were negatively impacted, particularly emotionally (Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Laukkanen et al. 2019).

3.3 Relationships on the Ward

Ten reviews highlighted the importance of relationships on the ward for staff in inpatient hospitals (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Fletcher et al. 2021; Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021; Westwood and Baker 2010; Wilson et al. 2021; Wyder et al. 2017). Overall confidence in this evidence was low (Table 1).

3.3.1 Therapeutic Relationship

Nursing staff were reported to agree that the therapeutic relationship was integral to care delivery (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021; Westwood and Baker 2010; Wilson et al. 2021; Wyder et al. 2017) and was facilitated by interpersonal skills (Delaney and Johnson 2014; Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Wyder et al. 2017), teamwork (Fletcher et al. 2021; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021; Wyder et al. 2017) and professional supervision (Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021). However, nurses and patients were reported to universally agree that negotiation could be more effectively used to manage patient aggression and violence (Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014).

Delaney and Johnson (2014) reported that nurses believed collaborative engagement with patients was meaningful and professionally satisfying in its own right, not just as it facilitated treatment. Therapeutic engagement was reportedly enhanced by staff finding meaning in patients' recovery journey on the ward, shared sense of humanity with patients, attunement, particularly at times of increased ward tension, maximising time with patients, rapport building through authentic, present and respectful communication, and being nonjudgmental and curious about patients' experiences of mental illness (Delaney and Johnson 2014). Nurses were also described as deliberately reducing the distinctiveness of their role on the ward and projecting an ‘unobtrusive’ manner in their interactions with patients to strengthen therapeutic engagement (Delaney and Johnson 2014).

Additionally, staff role modelling of trust and reliability with patients was reported to facilitate therapeutic engagement (Wilson et al. 2021), as was providing person-centred, recovery-oriented care. Examples provided to demonstrate the latter included using pro re nata medication or increasing observation (Wyder et al. 2017); however, it is unclear how ‘recovery-oriented’ these are in practice. Alexander and Bowers (2004) also reported that staff perceived that making morally censorious judgements of patient noncompliance contributed to therapeutic engagement. However, the authors noted that this might have been related to patient behaviours being decontextualised in the primary research study and/or that nurses' personal experiences of assault may influence their moral stance.

Nurses were described as believing that the most significant factors contributing to patient aggression were verbal abuse by staff and/or patients and patient mental illness, followed by limit setting, and interpersonal conflict (Fletcher et al. 2021). Hallett, Huber, and Dickens (2014) also reported that staff and patients believed changing the physical ward environment could prevent aggression even though it may not be regarded as a direct causal risk factor for violence.

3.3.2 Teamwork

Staff had mixed perceptions of the team atmosphere and collegial functioning in inpatient wards. Four reviews reported on staff's negative perceptions (Fletcher et al. 2021; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021; Wyder et al. 2017). Two reviews reported positive perceptions of staff, with collegiality and teamwork contributing to nurses' job satisfaction (Delaney and Johnson 2014) and strong leadership and having a shared vision of care and ward goals being reported to minimise perceived work-related stress (Wyder et al. 2017). In contrast, nurses were reported to think that teamwork was negatively impacted by competing understandings of care between different staff disciplines (Wyder et al. 2017) and between senior and junior nurses in acute wards (Fletcher et al. 2021). Furthermore, nurses were reported to believe that staff in other health professions tended to avoid complex clinical situations (crisis management and family liaison) (Delaney and Johnson 2014) and to experience frustration with colleagues, management and the health system (Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021).

3.4 Ward Rules

Ten reviews discussed the impact of ward rules on staff perceptions of inpatient wards (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Fletcher et al. 2021; Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014; Laukkanen et al. 2019; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Nelstrop et al. 2006; Scholes, Price, and Berry 2021; Wilson et al. 2021; Wyder et al. 2017). Overall confidence in this evidence was low (Table 1).

All the above reviews, except Fletcher et al. (2021), highlighted the idea that staff enforced ward rules in contrast to their values, beliefs or principles of trauma-informed care. Nurses were reported to perceive that they had little control over their nursing practice, yet, at the same time, they were aware they had substantial control over the day-to-day functioning of inpatient wards (Wyder et al. 2017). Similarly, physicians were described as perceiving they lacked choice about using chemical restraint, given the need to maintain the safety of service users and staff and the pressure to meet the needs and expectations of nursing staff (Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021). Nurses were described as simultaneously believing they provided ‘questionable’ care, given the circumstances, yet having pride in their ability to meet patients' needs while working in a flawed system (Delaney and Johnson 2014). Nurses were also reported to perceive a mismatch between restrictive hospital policies and ‘unreasonable’ organisational expectations to use a trauma-informed, person-centred approach that was simultaneously quantifiable, time-limited and task-focused (Wilson et al. 2021; Wyder et al. 2017).

Nurses were noted to find it challenging to balance restrictive practices with patients' rights and to sometimes disagree with aspects of involuntary treatment, perceiving that the necessity of enforcing such policies interfered with their capacity to provide authentic nursing care (Alexander and Bowers 2004) and that inpatients directed their anger and frustration about involuntary treatment at staff (Wyder et al. 2017). Furthermore, nurses were reported to believe there was a ‘subtle mismatch’ between the type of knowledge required to work within the medical model of psychiatry and the knowledge required to understand a patient's suffering (Delaney and Johnson 2014).

Additionally, ward routines and rules were reported to be important to staff perceptions of aggressive incidents (Fletcher et al. 2021) and violence prevention (Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014) and sometimes pose barriers to patient care if not applied flexibly (Delaney and Johnson 2014). Physician, nurse, occupational therapist and social worker perceptions of having low controllability of patients' aggression were linked to negative emotions towards patients, whereas low perceived patient controllability over their own emotions was linked with positive staff emotions because it denoted staff acceptance of the patient as a suffering individual rather than a deliberate perpetrator (Fletcher et al. 2021). It is perhaps not surprising then that clear ward routines and guidelines were reported to facilitate staff's sense of controllability over patient aggression (Fletcher et al. 2021) and that enhancing ward rule clarity was reported to boost staff–patient communication and staff morale (Alexander and Bowers 2004).

3.5 Knowledge and Experience

Nine reviews examined the impact of staff's knowledge and experience on their perceptions of inpatient wards (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Doedens et al. 2020; Gee et al. 2017; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Laukkanen et al. 2019; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Wilson et al. 2021; Wyder et al. 2017). Overall confidence in this evidence was low (Table 1).

Recovery-oriented training for all staff of adult and forensic units was found to significantly increase staff perceptions that ‘what [patients] say makes a difference in their treatment’, ‘staff spend time talking to and doing things with’ patients and that patients ‘would get out of the hospital and not come back’ as well as staff's perceived autonomy (Gee et al. 2017).

Nurses were reported to perceive that their experience and expert knowledge were important in supporting treatment adherence for pharmacotherapy (Wyder et al. 2017). Similarly, nurses were noted to link their level of experience with decision-making about coercive practices like seclusion and restraint (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Doedens et al. 2020; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Laukkanen et al. 2019). However, reviews varied in their reports of the direction of this effect. That is, whether greater seniority increased or decreased nurses' approval of coercive measures, which Doedens et al. (2020) suggested may be indicative of a cohort effect with nursing staff's attitudes reportedly becoming more critical of coercive practices since about 2010.

3.6 Service Delivery Issues

Six reviews examined the role of service delivery issues in influencing staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals (Delaney and Johnson 2014; Doedens et al. 2020; Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Richards et al. 2006; Wyder et al. 2017). Overall confidence in this evidence was low (Table 1).

Staff were described as facing service delivery issues, including clinical (intense and low visibility work), administrative (responsibility for non-nursing tasks) and organisational (lack of support) issues (Delaney and Johnson 2014) as well as perceiving that poor staffing and training levels interfered with violence prevention (Hallett, Huber, and Dickens 2014). Sociopolitical factors were also identified as influencing nurses' attitudes towards coercive measures (Doedens et al. 2020; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018), with nurses perceiving they were in a double bind where they might be blamed by (future) society for using coercion and for the detrimental effects of not using coercion (Doedens et al. 2020).

Nurses were reported to perceive that they experienced high levels of burnout, occupational stress and psychological distress (Delaney and Johnson 2014; Wyder et al. 2017) due, in part, to service delivery issues, though this was not supported by Richards et al.'s (2006) quantitative analysis of these issues. However, Richards et al.'s analysis was hampered by the heterogeneity and low quality of available data on these issues.

3.7 Coercive Measures

Eight reviews reported on staff perceptions of coercive measures (seclusion, physical restraint and/or chemical restraint) (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Delaney and Johnson 2014; Doedens et al. 2020; Jackson, Baker, and Berzins 2018; Laukkanen et al. 2019; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Nelstrop et al. 2006; Wyder et al. 2017). Overall confidence in this evidence was very low (Table 1).

There was considerable heterogeneity in nursing staff's reported attitudes towards the use of coercive measures, with variation according to the restrictiveness of the measure (Doedens et al. 2020; Laukkanen et al. 2019; Muir-Cochrane and Oster 2021; Nelstrop et al. 2006), country (Alexander and Bowers 2004; Laukkanen et al. 2019), gender of staff and patients, staff age and experience level (Doedens et al. 2020). Another review stated that other allied health staff believe coercive measures violate patient integrity and damage the therapeutic alliance (Laukkanen et al. 2019).

4 Discussion

This meta-review aimed to identify, summarise and synthesise the factors that staff report influence their perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals. Seven themes were identified from 15 included reviews: staff and patient safety, views on inpatients' experiences, relationships on the ward, ward rules, knowledge and experience, service delivery issues and coercive measures. There was considerable overlap in themes, as would be expected, given that improvements in one area can have a positive impact on other areas as well as staff perceptions of ward life.

As with inpatients (Modini, Burton, and Abbott 2021), staff tended to focus on ward safety, relational factors and coercive measures when expressing their views of inpatient psychiatric hospitals. Unsurprisingly, staff had a relational focus not only on staff–patient relationships but MDT relationships. Interestingly, unlike inpatients (Modini, Burton, and Abbott 2021), staff knowledge and experience, including training and treatment approach, was a relatively prominent theme in this meta-review. Although Modini, Burton, and Abbott (2021) suggested that inpatients routinely expect adequate treatment and benefit from it, it is not necessarily a salient factor for them. Whereas this review found that the literature on staff perceptions of ward life makes training and treatment approach a focal point, perhaps because it is a core aspect of care delivery that is readily modifiable with measurable benefits for treatment outcomes.

Additionally, staff had unique concerns about ward rules and routines, as well as service delivery issues, particularly their experiences of being overburdened by competing clinical, administrative and organisational priorities and demands to implement person-centred, recovery-oriented care within the task-focused medical model typically used in psychiatric hospitals. This supports calls in recent literature for new models of care in inpatient psychiatric hospitals (Ward-Miller et al. 2021), including clearer and more holistic standards, practices and training for staff (Gabrielsson et al. 2020; McIntosh and Gournay 2017; McKenna et al. 2014; Walker and McAndrew 2015), and self-determination regarding changes affecting psychiatric nurses (McIntosh and Gournay 2017). Although many hospital organisations and MDTs may be aware of the challenges and constraints of ward life outlined in this meta-review and may commonly employ strategies to minimise staff stress, maximise retention and improve ward culture, inpatient psychiatric hospitals struggling with staff burnout, conflictual ward cultures, high turnover rates and mental health staff shortages should directly target these issues. For example, facilitating more protected time for staff to interact with patients.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

Much of the literature reviewed here focused on staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals in the last 20–30 years. Only one included review directly considered whether staff views had changed over time. Most perceptions were drawn from staff working in inpatient psychiatric hospitals after the major shift away from ‘asylums’ towards greater community care of patients. Furthermore, the majority of included reviews did not differentiate between the age or experience levels of staff in reporting their perceptions of inpatient settings. Therefore, we likely did not see as much of a ‘cohort effect’ as we might have had the included reviews gone back further in time or delineated staff perceptions by age and experience levels. Future primary research should consider exploring this further.

Similarly, much of the literature in the included reviews focused on the perceptions of nursing staff rather than staff from other disciplines. although the views of nursing staff are important, with nurses making up the largest proportion of the mental health workforce internationally (AIHW 2022; Jones 2006; Søvold et al. 2021), their views are not the only ones worthy of consideration. Most notably, the perceptions of psychiatrists were absent. Psychiatrists tend to have leadership roles in MDTs, managing inpatient teams for long periods. They may therefore provide valuable insight not only into their role but into changes in staff perceptions over time. Consequently, future research into the perceptions of other staff should be prioritised.

Strengths of this meta-review include using a preexisting protocol for conducting meta-reviews of qualitative literature to maximise the systematic nature of the process and using the AMSTAR 2, a validated tool to assess the methodological quality of healthcare reviews, to assess for bias. Although a number of potential reviews were excluded as part of this latter process, this ensured that only the highest quality reviews were summarised and synthesised, enhancing confidence in the results of this meta-review. Similarly, a particular strength of this meta-review was the additional assessment of the quality of evidence at the level of each extracted theme, including the deduplication of fully overlapping data from original primary studies. However, this does not negate the fact that recall or selection bias in the original primary studies in the included reviews may carry over to this meta-review.

Overall, the highest quality evidence included in this meta-review came from the examination of themes of safety and staff views on inpatients' experiences, offering a reasonable basis for confidence in conclusions drawn from these findings. Other themes (relationships on the ward, ward rules, knowledge and experience, ward rules and service delivery issues) were rated low in confidence or very low in the case of coercive measures. The two most common issues affecting the confidence in the evidence underlying the identified themes were methodological quality (inappropriate/lack of examination of the risk of bias) and coherence. Issues with coherence affected all themes, indicating that the included reviews tended to inappropriately smooth out data, leaving out lower frequency cases (e.g., perspectives of non-nursing staff) or merging data across settings (acute and other wards) and time. To some extent, this smoothing over is inevitable in the review process, which typically aims to identify overarching patterns/themes. However, it suggests more focused research is warranted into these ‘smoothed over’ areas. It is also important to recognise that this meta-review used thematic synthesis to explore staff perceptions, which incorporates a degree of subjectivity, and over which there is debate as to the degree of bias this may introduce (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009). Efforts were made to minimise subjective bias by using a data saturation approach to maximise the thoroughness of data extraction and involving a second independent reviewer to assess that this had been achieved. Additionally, there were insufficient quantitative data to perform meta-analyses to judge the overall levels of staff morale, job satisfaction or burnout. This is another avenue for future research.

5 Conclusion

The findings of this meta-review suggest that a range of factors influence staff perceptions of inpatient psychiatric hospitals, some of which are specific to staff and others in concert with those identified by inpatients. Considering the perceptions of staff and patients is vital in making progress towards more humane, recovery-oriented and efficacious treatment in psychiatric hospitals. Failure to do so may have detrimental effects on factors like staff stress levels and retention rates, delivery of care and, potentially, treatment outcomes for inpatients.

6 Relevance to Clinical Practice

The themes identified by this meta-review offer avenues for the potential modification of policies, practices and organisational training programmes in inpatient psychiatric hospitals to benefit staff, inpatients and hospital organisations. For example, ways to increase staff retention and satisfaction and quality of patient treatment. This may, in turn, contribute to the reduction in high postdischarge suicide rates though further research is still required into the precise determinants of this.

Additionally, the themes identified through this meta-review provide insight into changing attitudes of inpatient psychiatric hospital staff over time and highlight present areas of concern to inpatient staff, which may be useful to senior staff and hospital management in appropriately directing staff support services and ensuring staff have avenues to raise concerns about related issues and advocate for innovation.

Author Contributions

All of the listed authors meet authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, and all authors are in agreement with the submission of this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnote

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.