An integrative review exploring the physical and psychological harm inherent in using restraint in mental health inpatient settings

Abstract

In Western society, policy and legislation seeks to minimize restrictive interventions, including physical restraint; yet research suggests the use of such practices continues to raise concerns. Whilst international agreement has sought to define physical restraint, diversity in the way in which countries use restraint remains disparate. Research to date has reported on statistics regarding restraint, how and why it is used, and staff and service user perspectives about its use. However, there is limited evidence directly exploring the physical and psychological harm restraint may cause to people being cared for within mental health inpatient settings. This study reports on an integrative review of the literature exploring available evidence regarding the physical and psychological impact of restraint. The review included both experimental and nonexperimental research papers, using Cooper's (1998) five-stage approach to synthesize the findings. Eight themes emerged: Trauma/retraumatization; Distress; Fear; Feeling ignored; Control; Power; Calm; and Dehumanizing conditions. In conclusion, whilst further research is required regarding the physical and psychological implications of physical restraint in mental health settings, mental health nurses are in a prime position to use their skills and knowledge to address the issues identified to eradicate the use of restraint and better meet the needs of those experiencing mental illness.

Introduction

The primary focus of this review is to explore the physical and psychological impact of physical restraint for people receiving inpatient mental health care. International agreement has sought to define physical restraint, describing it as ‘any action or procedure that prevents a person's free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to his/her body by the use of any method, attached or adjacent to a person's body that he/she cannot control or remove easily’ (Bleijlevens et al. 2016; p. 2307). In the United Kingdom (UK), physical restraint has been defined as ‘any direct contact where the intervener's intention is to prevent, restrict, or subdue movement of the body of another person’ (Department of Health (DH), 2014; p. 26). For the purpose of this integrative review, physical restraint refers to ‘any occasion in which staff physically hold the patient preventing movement, typically in order to prevent imminent harm to others, or self, or to give treatment, or to initiate others methods of containment’ (Bowers et al. 2012; p. 31), and will exclude restraints by means of equipment and technology.

For some time, progressive and critical service users have expressed concerns about the legitimacy and potentially harmful impact of coercion and restrictive practices (Cusack et al. 2016; Duxbury 2015; McKeown et al. 2017; Rose et al. 2015). Such concerns have contributed to recent interest in models of trauma informed care, particularly to the extent to which services may retraumatize individuals (Bloom & Farragher 2010; Muskett 2014; Sweeney et al. 2016). The more radical survivor movements argue that the use of physical restraint reveals a more extensive or epistemic violence visited by psychiatric services upon individual (Lieggo 2013; Russo & Berseford 2014). Representative staff organizations have claimed restraint as an employment relations issue, with a mixture of progressive and regressive strategies (McKeown & Foley 2015).

Background

Countries differ in their use of different forms of restraint, with containment methods used in some countries, yet not in others (Bowers et al. 2007); the same divergence has been evident in international policy (Royal College of Nursing 2008). However, in more recent years there has been an international policy shift to reduce restrictive interventions (McKenna 2016). For example, in the UK the DH (2014) has produced guidance for health and care staff in reducing restrictive interventions, whilst the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued guidelines on managing violence and aggression (NICE 2015). In addition to statutory organizations, campaign groups have also produced guidance to support individuals in challenging how restraint is used in mental health services (Mind 2015). Positive initiatives to promote patient-centred care, such as the ‘Safewards’ model, have also been implemented internationally (Bowers 2014).

Looking to a legal context, from a human rights perspective, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities arguably renders aspects of compulsion and coercion unlawful (Minkowitz 2006; Plumb 2015). More precisely, Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (2003) prohibits inhumane and degrading treatment, with poor practice in restraint falling within this category. Physical restraint can also be challenged under Article 8, respect for private life, and under Article 5, regarding deprivation of liberty/unlawful detention. Whilst specific international legislation around restrictive interventions will inevitably vary, in England and Wales the Mental Health Act 1983: Code of Practice (Department of Health 2015) identifies best practice in the use of restrictive interventions for people within mental health settings and detained under the Mental Health Act (1983, amended 2007). Additionally, from a safeguarding perspective, the Care Act (2014) in England sets out the legal framework for local authorities and partner agencies, in seeking to protect adults at risk of abuse or neglect. This would include any abuse or neglect experienced as a result of physical restraint.

Whilst international policy and legislation seeks to minimize restrictive interventions, research studies suggest physical restraint continues to raise concerns. For example, in the 10-year period, 2002–2012, there were 38 restraint-related deaths in the UK (Duxbury 2015) and approximately 1000 incidents of physical injury reported following restraint in 51 mental health trusts in England (Mind 2013). Regardless of policy, incidents of restraint in more recent years have increased, with 66 681 restraint episodes reported in 50 of 58 mental health trusts in England, 12 347 of which involved face-down restraint (Merrick 2016), leading to serious concern about its use (Care Quality Commission (CQC), 2017).

The misuse of physical restraint, deemed as abuse, also appears to be underreported by service users. Whilst some service users have reported the use of excessive force in their experiences of physical restraint (Brophy et al. 2016; Whitlock 2009), others believe they would not be taken seriously when reporting such practice (Cusack et al. 2016; Whitlock 2009). For some nurses, restraint is seen as a ‘necessary evil’ in controlling behaviour and preventing violence, thus leading to the normalization of restraint practice (Perkins et al. 2012). Evidence suggests at times restraint is used all too quickly, with nurses in one study referring to the use of restraint equating to a ‘bouncer mentality’ (Lee et al. 2003). Such beliefs and actions are often enmeshed within the culture of the ward and may contribute to the difficulties of introducing change (Pereira et al. 2006). In contrast, other studies have reported nurses expressing discomfort with using restraint, suggesting it can be demeaning for service users (Bonner et al. 2002; Duxbury 2002; Lee et al. 2003). These are important issues that nursing staff are well placed to address. Demonstrating compassionate attitudes and behaviours towards service users, and acting as positive role models for neophyte nurses and other healthcare staff may help to reduce, and subsequently eradicate, restraint (Bloom 2010). Chapman (2010) describes how this transmission of practices can occur in the course of forms of debriefing that serve simply to justify and reify the use of restraint, rather than learn constructive lessons.

Whilst research to date has reported on statistics regarding restraint, how and why it is used, and staff and service user perspectives about its use, there is limited evidence that directly explores the physical and psychological harm it causes to people being cared for within mental health inpatient settings. As a result, this integrative review aimed to explore this phenomenon.

Aim of the integrative review

The aim of this integrative review was to explore the physical and psychological impact of physical restraint on people admitted to mental health care inpatient settings.

Method

In undertaking this integrative review, both experimental and nonexperimental researches were included to ensure all findings were included (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). An integrative review was deemed as an effective approach, in that it ‘reviews, critiques and synthesises representative literature on a topic in an integrated way’ (Torraco 2005; p. 356). Cooper's (1998) framework for research synthesis was followed, which recommends a five-stage approach when undertaking a literature review: problem identification; literature review; data evaluation; data analysis; and presentation of results.

Problem identification

The focus of this review was to appraise and synthesize the available findings regarding the practice of physical restraint and the physical or psychological impact it has when used on those receiving care in mental health inpatient settings. Whilst Whitlock (2009) suggested underreporting of abuse caused by the misuse of physical restraint within mental health services, there appears to be a lack of comprehensive appreciation of how such abuse manifests in physical and psychological harm. Exploring and synthesizing the evidence relating to these phenomena may assist in developing a future research agenda.

Literature search

Using terms related to the components of the topic area (Table 1), five databases were searched, including CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and Cochrane. Hand-searching of reference lists within identified papers was also undertaken, resulting in further research for consideration. Journal searching, professional networking, and searches of the published work of authors, from key titles in the associated field of research, were undertaken to further ensure a detailed search was employed (Aveyard & Sharp 2013).

| Setting AND | Perspective AND | Intervention AND | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | Vulnerable adults | Behaviour control | Violence |

| OR | OR | OR | OR |

| Psychiatric hospitals | Adults at risk | Coercion | Abuse |

| OR | OR | OR | OR |

| Institutional setting | In-patient | Containment | Abuse of patients |

| OR | OR | OR | OR |

| Institution | Psychiatric patients | Control | Patient abuse |

| OR | OR | OR | OR |

| Institutional care | Mental health patients | Manual restraint | Abusive practice |

| OR | OR | OR | OR |

| Psychiatric unit | Consumer | Physical restraint | Sexual abuse |

| OR | OR | OR | OR |

| Nursing care | Client | Restraint | Trauma |

| OR | OR | OR | OR |

| Psychiatric nursing | Service user | Restraint physical | Risk |

| OR | OR | OR | |

| Psychiatric ward | Restrictive intervention | Risk of injury | |

| OR | OR | ||

| Psychiatric service | Adverse effect | ||

| OR | OR | ||

| Psychiatric unit | Adverse health care event | ||

| OR | OR | ||

|

Psychiatric care Psychiatric setting |

Adverse impact | ||

| OR | OR | ||

| Mental health ward | Elder abuse | ||

| OR | OR | ||

| Mental health setting | Harm | ||

| OR | OR | ||

| Mental health unit | Injury risk | ||

| OR | |||

| Physical abuse | |||

| OR | |||

| Safeguarding | |||

| OR | |||

| Safety behaviour | |||

| OR | |||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder |

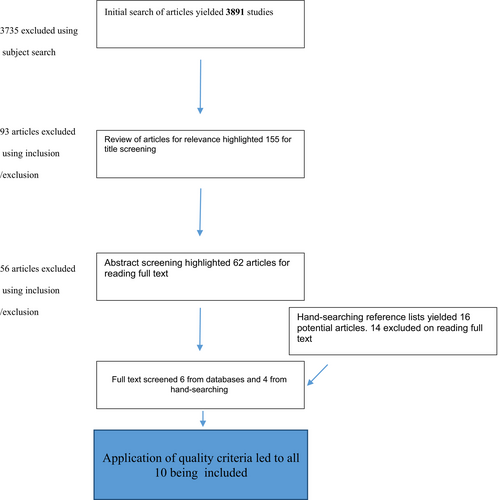

To avoid drift and further refine the search, inclusion and exclusion criteria were introduced (Aveyard 2010). As physical restraint can be used abusively, the year 2000 was deemed pivotal, as this was when the first national guidance attempting to define and address adult abuse in health and social care settings was published in the UK (Department of Health 2000). In the light of this, studies published from 2000 to October 2017 were included in the search. Other inclusion criteria were as follows: adults (over 18), mental health inpatient settings, physical and psychological harm as a result of restraint, and articles written in the English language. Exclusion criteria were as follows: those under 18, non-mental health inpatient settings, other forms of restraint, grey literature, and research papers in other languages. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies were included in the review. Given the lack of evidence to date, no systematic review was found. Figure 1 shows the literature search and papers retrieved during each phase of the search.

Data evaluation

There were three stages for screening the articles retrieved. The first stage included a database search through journal titles, where papers were set aside for further reading of the abstract. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were used to retrieve potentially relevant articles. The second stage involved reading the abstracts of each paper, again screening for relevancy, using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The third stage involved reading the residual articles in full and making the final decision as to whether they were relevant for inclusion in the review. Although duplicates are generally automated within the database platforms, some duplicates within individual databases had to be manually removed (Clapton 2010).

In line with the next stage of Cooper's Framework (1998), papers which met the inclusion criteria were then appraised. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools were used for this purpose. Although the CASP was developed to critique a wide range of literatures (Whittaker & Williamson 2011), an appraisal tool was not available for mixed-methods studies. In the light of this, Riahi's (2016) modified CASP appraisal tool was applied. Following Cooper's framework (1998), methodological features were assessed for overall quality. Additionally, papers were evaluated using Walsh and Downe's (2006) Quality Summary Score. This quality assessment tool gives evaluations from A to D, ranging from no or few flaws to significant flaws compromising the quality of the study, and D-rated papers are deemed of poor quality, and therefore, a decision was made to remove any papers assessed as a D rating at this stage. However, no papers were rated as D, which meant that all papers at this stage were included in the review. Each paper was appraised by three reviewers, and a comparison of findings took place to ensure rigour and consistency.

Ten papers were finally included in the review (see Fig. 1). Of the 10 papers included in the final analysis, one was quantitative (Steinert et al. 2007), two were mixed-methods (Haw et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2003), and seven were qualitative studies (Bonner et al. 2002; Brophy et al. 2016; Knowles et al. 2015; Sequeira & Halstead 2002, 2004; Wilson et al. 2017; Wynn 2004). Included in the seven qualitative studies, two papers reported on findings from the same study; however, each of these investigated differing participant perspectives, one being from the views of staff whilst the other exploring service user views. A decision was made to keep these separate for the purposes of this review, as each study identified some key differences within the themes.

Data analysis

Following the next stage of Cooper's (1998) framework, an analysis of data presented in the papers was undertaken. This encompassed constant comparison across the included papers to identify themes, patterns, and variations within the emergent findings, whilst splitting quantitative from qualitative findings. Constant comparison is acknowledged as an approach, which allows for systematic categories to form (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). A grid was devised to assist this process, and articles were read and reread, allowing distinct themes to emerge and variations to be acknowledged. In total, eight main themes emerged, with the focus of physical or psychological harm for users of mental health inpatient services who have experienced physical restraint. Table 2 summarizes the studies and the key themes arising within each paper, as well as the quality grading of individual papers.

| Authors, year, country | Study type and analysis | Aim | Sample and setting | Main themes from physical restraint | Quality grading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bonner et al. (2002) UK |

Qualitative semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis |

To establish feasibility of using semi-structured interviews with patients following restraint. To gather information on factors which patients and staff felt helpful or unhelpful in their experience of restraint following restraint and to report on lived experiences of people involved | 12 staff and six patients in an inpatient mental health ward in South of England |

Trauma/retraumatization Feeling ignored Inhumane conditions Distress Fear |

C |

|

Brophy et al. (2016) Australia |

Qualitative focus groups Inductive analysis (NVivo software) |

To examine the lived experiences of service users and carers around the use of seclusion and restraint | 30 mental health service users and 26 carers in four cities and one regional centre |

Trauma/retraumatization Inhumane conditions Fear Control Power |

C |

|

Haw et al. (2011) UK |

Mixed methods Qualitative thematic analysis Quantitative statistical analysis |

To report on forensic rehabilitation of inpatients’ experiences and preferences for physical restraint, seclusion, and sedation | 57 patients in a forensic psychiatric setting |

Feeling ignored Distress Dehumanization Power Calm |

B |

|

Knowles et al. (2015) UK |

Qualitative interviews Thematic analysis |

To examine the impact on the staff–patient therapeutic alliance | 8 patients on a medium-secure unit |

Power Dehumanization Trauma/retraumatization |

C |

|

Lee et al. (2003) UK |

Mixed methods Qualitative thematic analysis Quantitative SPSS statistical analysis |

To seek views of psychiatric nurses in their experience in use of restraint | 338 psychiatric nurses in regional, secure, and psychiatric intensive care units in England and Wales |

Dehumanization Power |

C |

|

Sequeira and Halstead (2002) UK |

Qualitative (grounded theory). Semi-structured interviews |

To examine the experiences of physical restraint procedures from a service user perspective | 14 inpatients in a secure mental health setting |

Power Distress Fear Control Calm |

A |

|

Sequeira and Halstead (2004) UK |

Qualitative (grounded theory). Semi-structured interviews |

To examine the experience of physical restraint by nursing staff in a secure mental health setting | 17 nurses in a secure mental health setting |

Trauma/retraumatization Distress Power |

A |

|

Steinert et al. (2007) Germany |

Quantitative SPSS statistical analysis | To look at how seclusion and restraint might cause post-traumatic stress disorder and revictimization | 117 mental health inpatients | Trauma/retraumatization | A |

|

Wilson et al. (2017) UK |

Qualitative thematic analysis | To improve understanding of restraint for both staff and patients, who have direct experience or have witnessed restraint | 13 patients and 22 staff in adult mental health inpatient environments |

Fear Power Dehumanization Distress |

A |

|

Wynn (2004) Norway |

Qualitative grounded theory Interpretive analysis |

To allow patient to share experiences of physical restraint | 12 mental health inpatients |

Trauma/retraumatization Distress Fear Control Power Calm |

B |

Results

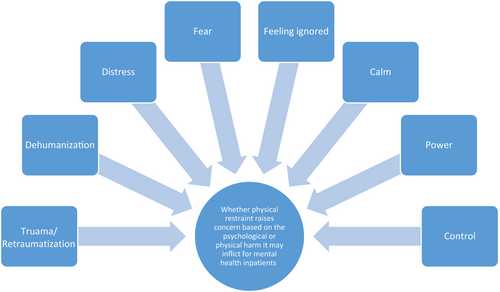

All 10 papers involved primary research, emanating from different countries – one from Norway, one from Germany, one from Australia and seven from the UK. The papers include both service user and staff perspectives on the use of physical restraint. The possibility of restraint being used abusively is implicit in some of these papers (Brophy et al. 2016; Haw et al. 2011; Knowles et al. 2015; Wynn 2004). Although eight differing themes emerged related to the aims of this review, several themes were naturally interrelated. One example is the themes of power and control, and this will be elaborated upon within this review. The eight themes which emerged from this review are Trauma/retraumatization; Distress; Fear; Feeling ignored; Control; Power; Calm; and Dehumanizing conditions. These are visually displayed in Figure 2.

Trauma/retraumatization

The theme of trauma and retraumatization was identified in five studies (Bonner et al. 2002; Brophy et al. 2016; Sequeira & Halstead 2004; Steinert et al. 2007; Wynn 2004). Three (50%) of the participants in one study (Bonner et al. 2002), which sought to examine people's experiences following a restraint incident, reported how physical restraint retraumatized them due to past abusive incidents. For one participant, this had involved a previous experience of rape, whilst for another, physical restraint brought back memories of childhood abuse. Likewise, in Wynn's (2004) study, focusing on patients’ experiences of physical restraint, two of three female participants and one male participant reported physical restraint had brought back memories of previous trauma. The male participant reported how difficult feelings were brought back from childhood experience in hospital, whilst both female participants described how physical restraint reignited memories of sexual abuse, with one reporting how it had reminded her of ‘awful things that happened to me as a child’ (Wynn 2004; p. 132).

Staff perspectives concerning the use of restraint and its impact of retraumatization were reported by Sequeira and Halstead (2004); however, in the same study other staff described how they were ‘hardened’ to the experience of restraint, with a significant number suggesting that they had no emotional reactions. Brophy et al. (2016), focusing on the lived experiences of people who had been restrained, suggested the trauma of actually being physically restrained was ‘antirecovery’; many participants raised concerns, not only about retraumatization, but how being restrained led to fear regarding future treatment. One participant, a carer, explained how her son was in fear of being readmitted to mental health wards, due to past restraint (Brophy et al. 2016).

Similarly, trauma was a concern raised by Knowles et al. (2015). Indeed, one patient was distracted within the research interview itself by the thoughts of previous restraint and reported how much of their time was occupied with vivid thoughts and dreams about restraint, which further suggests continued trauma because of the restraint episode itself.

Feeling ignored

Another emerging theme was the sense of participants feeling that their wishes and feelings were ignored by staff. In Bonner et al.'s (2002) study, three (50%) of the participants interviewed reported feeling distressed prior to restraint, but believed this was ignored by staff. One participant articulated how being ignored caused her to start shouting and screaming, and it was at this point staff restrained her. The psychological effects of being ignored, and her consequential behaviour, led her to experience feelings of shame and isolation following her restraint. Such feelings were seen as important issues by the participants, who believed if staff had intervened earlier in a more positive way, they might have de-escalated the situation.

In contrast, a study by Haw et al. (2011) reported on forensic inpatients’ experiences and preferences for physical restraint, seclusion, and sedation. When asked about making an advance statement about physical restraint, some participants reported how physical restraint was unacceptable to them. An advance statement would allow a written plan to be made about how best to manage their behaviour if they became agitated. However, in this study 10.5% of participants stated how they had made an advance statement about restraint, but there was no evidence of this in their case notes or care plans. This could be seen as another way in which service users are ignored. In the UK, the Mental Capacity Act (2005) is clear that advance statements should be considered part of the decision-making process within all healthcare settings. Of the 79 inpatients interviewed in Haw et al.'s study, 43 felt physical restraint should not be used at all, 38 suggested how talking might calm them down, and 39 participants felt sitting up during restraint would assist breathing. Haw et al. (2011) concluded it is best practice for patients to be fully involved in decisions made about their care as far as possible, perhaps going some way to demonstrate how their opinions and personal knowledge of self are valued and respected by staff.

Dehumanization

Another predominant theme in several of the studies reviewed was that of dehumanization in the perceived inhumane conditions present when people were restrained. One participant in Bonner et al.'s (2002) study described being left in urine soaked clothing for 3 hours following restraint, and reported being too ashamed to tell anyone. In Brophy et al.'s (2016) study, participants made links to poor practice, with feelings of being treated as ‘subhuman’ in the act of physical restraint, perhaps reinforcing any existing feelings of worthlessness.

In two of the studies (Brophy et al. 2016; Haw et al. 2011), patients found staff to lack empathy, with some describing staff as uncaring. Patients in Wilson et al.'s (2017) study echoed the feeling of being treated as ‘subhuman’, describing how they had they found physical restraint to be dehumanizing, with one participant feeling that they were not treated as ‘decent human beings’ (Wilson et al. 2017; p. 504).

Excessive force was reported to be used by staff during physical restraint. Lee et al. (2003) suggested restraint was being reported as a ‘legal’ way to hurt people, rather than being used as a last resort. In Lee et al.'s (2003) study, concerns were raised regarding joint locks and flexion being used to induce pain and achieve adherence. Haw et al. (2011) found that excessive force and pain were also reported, the former being a feature of care and the latter being the commonest sensation reported. In the same study, participants expressed concern that staff were punishing them and exerting power over them. Feeling ‘punished’ could reinforce feelings of self-blame, worthlessness, and/or low self-esteem, whilst experiencing powerlessness can lead to a person believing they are no longer in control of their life. One participant said that they felt staff ‘abused them’ and told them that they were ‘stupid’.

Similarly, concerns about excessive force were reported by Knowles et al. (2015), and patients reported that its presence during restraint made them feel abused, worthless, helpless, and demeaned. The potentially abusive nature of restraint and helpless felt by patients can also be linked with the imbalance and misuse of power, which is another theme within this review.

Distress

Given the previous theme, it is not surprising that the most common theme to emerge from the papers in this review was the distress caused by physical restraint. In Bonner et al.'s (2002) study, there was particular concern from two female participants when restrained by male staff members. One participant felt staff were going to kill her. Nurses also reported personal distress, describing feeling uncomfortable about undertaking restraint. This distress continued following restraint for both service users and staff, with fear of future incidents occurring in both groups (Bonner et al. 2002).

In Haw et al.'s (2011) study, 15 of the 57 participants reported how restraint brought about unpleasant thoughts, accompanied by feelings of humiliation and loss of dignity. Again the theme of distress resonates, in part, with the theme of dehumanization. In Wynn's (2004) study, participants reported how restraint harmed their integrity, making them feel anxious, angry, hostile, and distrustful of staff. Others reported that restraint had been unnecessary and that they had been unfairly treated. One participant went so far as to suggest restraint was abusive. In comparison, others felt it was necessary to contain a situation; however, no one perceived it to be positive (Wynn 2004).

In Wilson et al.'s study Wilson et al. (2017), the most common theme found was the distressing impact of restraint reported both by staff and by patients, particularly so when witnessed for the first time. In this study, one patient reported being ‘horrified’ (Wilson et al. 2017; p. 503) about the amount of physical restraint they had witnessed on the ward. However, two staff members in this study reported no emotional impact on themselves and suggested restraint was a necessary part of the job, perhaps implying that staff did not envisage a restraint-free environment (Wilson et al. 2017).

Sequeira and Halstead (2002) found that most participants reported negative psychological impact, describing a sense of fear and panic at the possibility of restraint being carried out, and that ‘something horrible was going to happen’ (Sequeira & Halstead 2002; p. 13). Participants reported the way in which nurses spoke during restraint was particularly upsetting, with one participant reporting ‘they talk and joke amongst themselves…You get angry, I get angry then’ (Sequeira & Halstead 2002; p. 13). It was suggested nurses use laughter to reduce stress during physical restraint, whilst others reported no emotional response and working on automatic pilot during restraint (Sequeira & Halstead 2004). Gender and status appeared to play a role with regard to experiences of restraint. Several female qualified staff expressed substantial distress about restraint, whilst unqualified male staff more commonly reported a degree of detachment and indifference to service users being restrained. Some staff reported anger towards service users who were perceived as intentionally bringing about having to use physical restraint on a frequent basis (Sequeira & Halstead 2004).

Fear

Staff are frightened…. there's a culture of fear in Australia like fear of difference, I think it adds to it (Brophy et al. 2016; p. 8)

In Wynn's study (2004), participants reported being fearful of future restraint because of their previous experiences, with one female participant reporting how restraint itself made her feel increasingly scared and aggressive. These findings are in keeping with earlier research (Sequeira & Halstead 2002), whereby participants’ fear of future restraint is based on their experience of previously being restrained and its long-lasting effects, such as poor sleep and nightmares. Similarly, fear, both during and following restraint, was also reported in Wilson et al.'s (2017) study, where a culture of fear was reported as being present throughout the patient journey. One patient described her fear of future restraint was because of a previous incident, when excessive force had been used by four staff members, as she had been dragged to the floor, on her knees, and taken to her bedroom. Although staff members in this study acknowledged fear felt by patients, a large proportion of staff also cited their own fear. This was particularly so when witnessing or carrying out restraint, for the first time. This suggests that restraint is a negative experience for both staff and patients.

Control

Brophy et al. (2016) found that restraint was deemed as a way to control patients, using excessive force. One participant reported the use of excessive force involving multiple staff. Furthermore, restraint was reported as a first, rather than last resort in responding to patients with mental health distress. Lack of de-escalation was linked to poor practice, the latter being the result of organizational cultures and staff attitudes (Brophy et al. 2016). Wynn (2004) found several participants reported that an approach, which would have affirmed their security in an unthreatening way, may have calmed the situation. Participants believed they were ‘pushed’ to defend themselves as a means of control. One participant commented ‘I think things would have turned out better…if they had left me alone in my room’ (Wynn 2004; p. 131). Other participants reported that they understood their behaviour needed to be controlled due to risks to themselves or others because of their distress.

Sequeira and Halstead (2002) found participants’ loss of control over their behaviour left them feeling degraded and out of control. A subset of female participants felt that their agitation, before restraint, made them feel out of control, and they wanted staff to take control. The women in this subset also reported how they purposely brought about restraint to gain control over the way they were starting to feel. However, as discussed previously, staff felt anger at patients who they felt purposely brought about restraint (Sequeira & Halstead 2004).

Power

Power and its potential misuse were evident in the findings of several studies. Such power manifested in excessive force being used in restraint (Brophy et al. 2016; Haw et al. 2011; Knowles et al. 2015), or when used as a first resort for managing a patient, to control them (Knowles et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2003).

Wynn (2004) took the ideology of control one step further, suggesting restraint to be an abuse of power, used by staff to display power over patients. Several participants reported that they were frightened of restraint occurring if they failed to follow staff directions. This fear continued after the restraint episode, as several participants expressed ongoing anxiety about restraint being used again. Serious concerns were raised by Lee et al. (2003) over the potential abuse of power by staff, with reports of them adopting a ‘bouncer mentality’. Many patients alleged they had experienced physical pain or injury because of physical restraint, which also evoked worries about being injury.

Haw et al. (2011) also found participants believed restraint was used to punish them, and excessive power and undue force were used.

Similarly, Sequeira and Halstead (2002) reported restraint being used as a punishment, with several participants feeling this led to further violence and aggression, and therefore further additional restraint.

Knowles et al. (2015) suggested that the power imbalance between staff and patients might add to an abusive dynamic, with several patients in this study reporting how they viewed staff as powerful perpetrators, with patients being the victims. Patients also characterized restraint as barbaric, mediaeval, and torturous. In the same study, two patients reported being interviewed in seclusion by staff following physical restraint, during which time they were asked to admit fault for the restraint occurring, with one participant saying that they admitted fault for fear that they would not be released from seclusion, unless they did so.

Brophy et al. (2016) reported restraint made participants feel powerless and invoked a sense that they would not be believed if they reported abusive practice. In Brophy et al.'s study, the use of excessive force to prevent further escalation of a potential situation and combat risk was deemed as poor practice. The harm caused by this was perceived as being the result of the deep-rooted effect of excessive force and the breaching of human rights, particularly in respect of dignity. Carers also felt powerless, especially when not being listened to by staff, yet they believed they knew the patient best (Brophy et al. 2016). The harm viewed by service users and carers was deemed as long-standing and usually retraumatizing (Brophy et al. 2016).

Similarly, Wilson et al. (2017) found how restraint was considered a demonstration of power that staff have over patients, leaving them with a wholly negative experience, following restraint. One patient made comparisons to being in prison, referring to some staff being like ‘prison wardens’ (Wilson et al. 2017; p. 505). One staff member in this study acknowledged the patient–staff power dynamic, recognizing restraint as a ‘symbol of strength and power that staff have over patients’ (Wilson et al. 2017; p. 504).

Calm

A surprising theme that emerged from the review was the calming aspect of being physically restrained, which was highlighted in three of the studies. Wynn (2004) found that whilst participants reported anxiety, fear, and anger at being restrained, some participants reported how physical restraint had a calming effect. Female participants were found to instigate restraint to release feelings of upset and agitation, but only when being restrained by female members of staff (Sequeira & Halstead's 2002). A similar finding was reported by Haw et al. (2011), who suggested that whilst seclusion was reported to have a more calming effect than that of physical restraint, the latter was deemed to have the potential to de-escalate the situation and promote personal reflection. However, Haw et al. (2011) argue that the negative impact of physical restraint far outweighs any positive implications.

Discussion

The emerging themes from this review suggest that physical restraint in some instances can and does lead to physical and/or psychological harm for those being cared for within inpatient mental health settings. Such harm can manifest in several ways. Service users can be traumatized due to the restraint itself or retraumatized following past trauma (Bonner et al. 2002; Brophy et al. 2016; Knowles et al. 2015; Sequeira & Halstead 2004; Steinert et al. 2007; Wynn 2004). Fear, and its potential for becoming a feature of care, from the perspectives of staff and service users before, during, and following restraint, was evident (Bonner et al. 2002; Brophy et al. 2016; Sequeira & Halstead 2002; Wilson et al. 2017; Wynn 2004). Further physical and psychological impacts of physical restraint include excessive control by ward staff, the physical harm being caused through physical pain or injury and the latter, psychological harm, being a feeling loss of control over one's life (Brophy et al. 2016; Knowles et al. 2015; Sequeira & Halstead 2002; Wynn 2004). Such physical and psychological implications can result in fear and anxiety around future restraint (Brophy et al. 2016; Knowles et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2017; Wynn 2004).

Dehumanization was also a felt experience associated with restraint (Bonner et al. 2002; Brophy et al. 2016 Haw et al. 2011; Knowles et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2017). Patients feeling ignored when they need support (Bonner et al. 2002) will have a negative psychological impact within the studies in which participants who experienced this described feeling ‘subhuman’, having a sense of ‘otherness’ both during and following restraint (Brophy et al. 2016; Knowles et al. 2015). The ignoring of individual's preferences through advance statements has been defined in legislation through the Mental Capacity Act (2005), and it is best practice for patients to be fully involved in their care as far as possible (Haw et al. 2011). The distressing experience of restraint from the perspectives of both patients and staff can impact on person's well-being (Bonner et al. 2002; Haw et al. 2011; Sequeira & Halstead 2002, 2004; Wynn 2004). For some participants within the studies, it was felt their life was threatened during restraint (Bonner et al. 2002). Conversely, for a minority of participants, physical restraint was reported as a positive intervention, being viewed as a way to calm them, letting others take control of their behaviour (Haw et al. 2011; Sequeira & Halstead 2004; Wynn 2004).

These findings are not unique in that other studies, in different settings and with different service user groups, report findings similar to those identified in this review. Studies of restraint in other types of settings, such as in learning disability facilities (Fish & Culshaw 2005; Jones & Kroese 2006), report how restraint techniques have the potential to cause physical and psychological harm (Parkes 2002; Parkes et al. 2011; Stubbs & Hollins 2011). Service users in other settings also reported the physical and psychological implications of harm as a result of physical restraint, particularly when it was misused. For example, physical harm related to being sat on, patients having their thumbs bent back, whilst psychological harm resulted from verbal abuse (Fish & Culshaw 2005; Jones & Kroese 2006).

Those who are restrained may be the most vulnerable service users. In a study by Hammer et al. (2010), 70% of patients who were secluded and restrained had histories of childhood abuse, reflecting the theme of trauma and retraumatization found in this current review. Furthermore, patients who experience seclusion and restraint most frequently have been reported as being 75 times more likely to have been subjected to physical abuse (Beck et al. 2008). Restraint use has been reported as a first response by staff, when they have perceived that their safety or the safety of others has been at risk (Duxbury 2002; Foster et al. 2007; Perkins et al. 2012), but evidence suggests an overestimation of risk based on service user behaviour (Foster et al. 2007). Additionally, fear based on incidents escalating to violence has led to an overestimation of the perceived threat and may prevent staff from looking for alternative ways of providing more therapeutic encounters (Duxbury 2002; Foster et al. 2007; Perkins et al. 2012). In a study by Perkins et al. (2012), nurses reported that restraint is a ‘necessary evil’ in controlling behaviour, and when staff consider individuals to be dangerous, aggressive, or difficult to manage, restraint can often be used in an arbitrary way (Gudjonsson et al. 2004; Keating & Robertson 2004). Likewise, such views can be part of a ward culture and this can prove challenging to change (Pereira et al. 2006). Good mental health nursing is predicated on therapeutic partnerships between service users and staff (Warne & McAndrew 2004), with good communication and interpersonal skills having the potential to prevent or minimize the need for restraint (Cusack et al. 2016). In the light of this and the evidence presented in this study, mental health nurses are well positioned to use their skills and knowledge positively to promote therapeutic engagement and eradicate physical restraint.

Limitations

A limitation of this integrative review is the small number of papers meeting the inclusion criteria. Generalization in other countries and settings may be limited, as restraint is practised differently across the globe which may favour different forms of restraint, such as equipment (Bowers et al. 2007), making comparisons difficult.

Conclusion

New insights have been gained through synthesizing findings from primary studies and providing new information, which adds to an existent, but small body of evidence regarding the physical and psychological implications of restraint from a service user perspective. Retraumatization, dehumanization, distress, fear, abuse of power, control – both wanted and unwanted – and feeling of being ignored were all important themes emerging from the data. All of these themes could be readily addressed by those working within mental health settings. There appears to be a gap in knowledge surrounding the narratives of service users who have experience of being physically restrained. This group of service users have unique and invaluable insight, and the future exploration of personal stories regarding the physical and psychological implications of physical restraint in mental health settings would be helpful in gaining a more in-depth understanding of this phenomenon and thus enable the quality of inpatient mental health care to be improved.

Implications for Practice

Nurses within mental health services represent the majority of the workforce; therefore, their ability to engage service users as active partners in their care may reduce restraint-related incidents. In the light of this, education and training will have a pivotal role in seeking to reduce restrictive interventions by promoting initiatives, such as ‘Safewards’ (Bowers 2014) and ‘Restrain Yourself’ (Advancing Quality Alliance 2014), the latter being adapted from the six core strategies of restraint reduction (Huckshorn 2005). Such initiatives are fundamental to promoting positive therapeutic alliances between service users and staff, as well as managing challenging behaviour. Recognizing service users as active partners in their care should be the foundation of good practice. Involving service users in their own care planning has the potential to ensure they are empowered, promoting feelings of being more in control of their lives, and acknowledging their unique knowledge in relations to their illness experiences.

Likewise, further studies are needed to explore the perceptions of service users who have experienced physical restraint within mental health settings to improve services and better meet the needs of those experiencing mental distress.