Evidenced-based clinical practice guideline for upper tract urothelial carcinoma (summary – Japanese Urological Association, 2014 edition)

Abstract

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma is more rare than bladder cancer, although they are both categorized as urothelial carcinoma. Because of the low incidence, little clinical evidence is available regarding the treatment of the former. However, recently such evidence has slowly begun to accumulate. The guideline presented herein was compiled for the purpose of ensuring proper diagnosis and treatment by physicians involved in the treatment of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. We carefully selected 16 clinical questions essential for daily clinical practice and grouped them into four major categories: epidemiology, diagnosis, surgery and systemic chemotherapy/other matters. Related literature was searched using PubMed and Japan Medical Abstracts Society databases for articles published between 1987 and 2013. If the judgment was made on the basis of insufficient or inadequate evidence, the grade of recommendation was determined on the basis of committee discussions and resultant consensus statements. Here, we present a short English version of the original guideline, and overview its key clinical issues.

Abbreviations & Acronyms

-

- BCG

-

- bacillus Calmette–Guérin

-

- CIS

-

- carcinoma in situ

-

- CQ

-

- clinical questions

-

- CR

-

- complete response

-

- CSS

-

- cancer-specific survival

-

- CTU

-

- computed tomography urography

-

- eGFR

-

- estimated glomerular filtration rate

-

- GC

-

- gemcitabine and cisplatin

-

- GFR

-

- glomerular filtration rate

-

- IVU

-

- intravenous urography

-

- JAMAS

-

- Japan Medical Abstracts Society

-

- LN

-

- lymph node

-

- LND

-

- lymph node dissection

-

- LVI

-

- lymphovascular invasion

-

- MRI

-

- magnetic resonance imaging

-

- MVAC

-

- methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin

-

- OS

-

- overall survival

-

- PS

-

- performance status

-

- RFS

-

- recurrence-free survival

-

- RNU

-

- radical nephroureterectomy

-

- RP

-

- retrograde pyelography

-

- UTUC

-

- upper tract urothelial carcinoma

1. Introduction

UTUC, along with bladder cancer, are histopathologically categorized as urothelial carcinomas. These types of cancers share a number of common risk factors, and are very similar in terms of current regimens of systemic chemotherapy. Unfortunately, UTUC is much less common than bladder cancer. Therefore, little clinical evidence is available, and no attempt has been made in Japan to compile a treatment guideline for UTUC to date. However, such evidence has recently begun to accumulate, albeit slowly, prompting our plan to establish an evidence-based guideline for the proper diagnosis and treatment of the uncommon cancer type. For this purpose, we, the preparation committee, determined CQ of the highest priority with regard to UTUC targeted at physicians' involved in its treatment, gathered as much related evidence as possible and obtained answers. After clarifying the inadequacy of evidence at the time of compilation, we aimed to produce a guideline that would stimulate further build-up of clinical evidence. We also developed the grades of recommendation through unanimous agreement. This guideline is expected to help standardize the diagnosis and treatment of UTUC, and improve the treatment outcomes.

Guideline development process

When we first planned to create a guideline for physicians for the treatment of UTUC, a total of 19 committee members were chosen (Table 1). The committee carefully determined 16 CQ essential for daily clinical practice, and grouped them into four major categories: epidemiology, diagnosis, surgery and systemic chemotherapy/other matters. Specific keywords were identified for each CQ and searched in two databases, PubMed and JAMAS, to locate articles published between 1987 and 2013. Based on the findings of the literature search, each member of the guideline committee drafted a review of the topic along with answers to CQ with descriptions. The content of the draft was then polished through several critical readings by multiple committee meetings, leading to a unanimous final draft. The grades of recommendation used in this guideline are shown in Table 2. When the evidence was insufficient or of an inappropriate level to make the judgment, the grade of recommendation was determined according to committee discussions and resultant consensus statements.

| Chairperson | Mototsugu Oya | Professor, Department of Urology, Keio University School of Medicine |

| Committee members | Tomohiko Ichikawa | Professor, Department of Urology, Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine |

| Hiroyuki Nishiyama | Professor, Department of Urology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba | |

| Masahiro Jinzaki | Professor, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Keio University School of Medicine | |

| Takao Kamai | Professor, Department of Urology, Dokkyo Medical University | |

| Akihiro Kawauchi | Professor, Department of Urology, Shiga University of Medical Science | |

| Hiromitsu Mimata | Professor, Department of Urology, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University | |

| Tsunenori Kondo | Associate Professor, Department of Urology, Tokyo Women's Medical University | |

| Atsushi Takenaka | Professor, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Tottori University Faculty of Medicine | |

| Hirotsugu Uemura | Professor, Department of Urology, Kinki University Faculty of Medicine | |

| Hideyasu Matsuyama | Professor, Department of Urology, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine | |

| Masato Fujisawa | Professor, Division of Urology, Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine | |

| Haruki Kume | Associate Professor, Department of Urology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo | |

| Tomohiko Asano | Professor, Department of Urology, National Defense Medical College | |

| Norio Nonomura | Professor, Department of Urology, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine | |

| Naoya Masumori | Professor, Department of Urology, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine | |

| Chikara Ohyama | Professor, Department of Urology, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine | |

| Document retrieval | Shiro Hinotsu | Professor, Center for Innovative Clinical Medicine, Okayama University Hospital |

| Executive office | Eiji Kikuchi | Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, Keio University School of Medicine |

| Grades of recommendation |

|---|

| A. Implementation is highly recommended on the basis of robust scientific evidence. |

| B. Implementation is recommended on the basis of some scientific evidence. |

| C1. Implementation is recommended, but no scientific evidence is available. |

| C2. Implementation is not recommended because of lack of scientific evidence. |

| D. Implementation is not recommended on the basis of scientific evidence demonstrating ineffectiveness or hazard. |

Clinical questions and answers addressed in this guideline

Table 3 shows the 16 CQ and answers addressed in this guideline.

| Category | CQ number | CQ | Answer | Recommendation grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | 1 | What are the risk factors of UTUC, including cigarette smoking? | Smoking and occupational exposure to aromatic amines are risk factors in common with bladder cancer. Those specific to UTUC include exposure to phenacetin or aristolochic acid. | |

| 2 | What is the association between UTUC and bladder cancer? | Urothelial carcinoma is characterized by multiple tumors, both spatially and temporally, found anywhere along the urinary tract. After treatment for UTUC, bladder cancer occurs in 15–50% of cases. A history of concurrent bladder cancer is also not uncommon. UTUC is closely associated with bladder cancer. | ||

| Diagnosis | 3 | Is CTU effective in the diagnosis of UTUC? | When UTUC is strongly suspected, IVU, along with ultrasonography, has been the method of choice for detecting UTUC; however, recently, CTU is recommended as the first choice. CT is also used for clinical staging. Thus, CTU is the first-choice approach for both diagnosis and clinical staging of UTUC. | B |

| 4 | Is ureteroscopy effective in the diagnosis of UTUC? | Ureteroscopy is effective for the detection and definitive diagnosis of UTUC. However, ureteroscopic tumor biopsy has an unfavorable positive predictive value for definitive cancer diagnosis; thus, results of urine cytology and finding of ureteroscopy should also be taken into account for making a final diagnosis. | C1 | |

| Surgical treatment | 5 | Is laparoscopic surgery recommended for RNU? | For UTUC, laparoscopic surgery is less invasive and does not have a worse oncological outcome in ≤T2 cases than open surgery; thus, it is recommended for RNU when performed by an adequately skilled surgeon. | B |

| 6 | Is LND recommended for RNU? | LND has both diagnostic and therapeutic roles. The diagnostic role is stratification of poor prognosis patients with positive LN metastasis derived from LND. The therapeutic role is also supported by a number of studies, showing prognostic advantages of LND in ≥pT2 cases. Therefore, LND is recommended in cases of progressive UTUC with suspected muscle invasion. | C1 | |

| 7 | What techniques are available for bladder cuff excision in RNU? | Extravesical, transvesical and endoscopic approaches are available, each with its own surgical techniques. At present, the best technique should be selected case-by-case in considering various factors, such as the possibility of local recurrence or tumor seeding, procedural invasiveness and operator's skillfulness. | C1 | |

| 8 | Is RNU recommended for pure CIS of the upper urinary tract? | RNU is recommended for pure CIS of unilateral upper urinary tract accompanied by a healthy contralateral kidney. | B | |

| 9 | Is neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy recommended for RNU? | Adjuvant chemotherapy may be considered for ≥pT3 or pN+ UTUC. | C1 | |

| 10 | What are intravesical recurrence rates after RNU and related prognostic factors? | Following RNU, intravesical recurrence occurs in approximately 15–50% of cases. Many prognostic factors for intravesical recurrence have been suggested; however, none of them have been validated. | ||

| 11 | What examinations are recommended during postoperative follow up of RNU? | No clear follow-up protocols are available; however, periodic CT examination is essential to monitor local recurrence/metastasis and recurrence in the contralateral upper urinary tract. Cystoscopy and urine cytology are also recommended to monitor intravesical recurrence. | B | |

| 12 | What cases are indicated for ureteroscopic kidney-sparing surgery? | Kidney-sparing surgery can be considered in cases of localized UTUC in solitary kidney or bilateral localized UTUC, those with impaired renal function, or those with poor PS to preserve renal function and avoid hemodialysis. | C1 | |

| Systemic chemotherapy and others | 13 | Is instillation of BCG or an anticancer drug into the upper urinary tract recommended as kidney-sparing therapy? | Long-term preservation of renal function may become possible in some cases of pure CIS of the upper urinary tract after anterograde or retrograde instillation of BCG into the upper urinary tract. The approach can be considered for cases of pure CIS of the upper urinary tract in solitary kidney or bilateral cases, those with impaired renal function, or those with poor PS. | C1 |

| 14 | What chemotherapeutic regimens are available for metastatic or recurrent UTUC? | Regimens employed for metastatic/recurrent (local recurrence) UTUC include GC or MVAC therapy, the same regimens for metastatic/recurrent bladder cancer. | B | |

| 15 | What chemotherapeutic regimens are available for patients with impaired renal function? | No chemotherapeutic regimens have been established for cases of UTUC with impaired renal function. Because renal function is inevitably reduced after RNU, cisplatin-based perioperative chemotherapy should preferably be administered as neoadjuvant therapy, particularly when renal function requires careful management. | C1 | |

| 16 | Is radiation therapy alone effective for UTUC? | No reports exist on treatment outcomes of radiation therapy alone for cases of UTUC without a history of surgical treatment. As adjuvant postoperative therapy, radiation therapy has been evaluated by small-scale, retrospective studies only; thus, no clear evidence on the effectiveness of radiation therapy is available at present. | C2 |

2. Epidemiology

Cancerous lesions of the renal pelvis and ureter are malignant tumors that arise from the urothelial (transitional cell epithelium) mucosa of the renal pelvis or ureter. Over 90% of these tumors are histopathologically categorized as urothelial carcinoma, whereas few cases are identified as squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma. UTUC is much less common than bladder cancer, and only accounts for approximately 5% of all urothelial carcinoma cases. Ureteral tumors are particularly rare; their incidence rate is approximately one-quarter of that of renal pelvic tumors.1 UTUC is mostly found in patients aged in their 50s to 70s, and its incidence is twofold higher in men than in women.2, 3

Causes

Risk factors of UTUC are cigarette smoking, medication, chronic infection, exposure to carcinogenic chemicals and occupational carcinogenesis. Of these, smoking is by far the most important, with a threefold higher risk of onset in smokers and 7.2-fold higher risk in long-term (≥45 years) smokers than in non-smokers.4 With regard to medication, long-term exposure to or abuse of cyclophosphamide5 or phenacetin6 can increase the risk of onset. Chronic bacterial infection associated with urolithiasis or urinary obstruction is another risk factor, particularly in histological squamous cell carcinoma. Furthermore, occupational exposure to substances used in industries, such as petroleum, coal, asphalt and tar, has been linked to a four- to fivefold increase in the risk of onset. Other factors include exposure to aristolochic acids, such as those found in certain plants endemic to the Balkan Peninsula that are known to cause Balkan endemic nephropathy, or those present in herbal medicine used in Taiwan that lead to the onset of Chinese herbs nephropathy; both are linked to UTUC.7, 8

Association between UTUC and bladder cancer

Urothelial carcinoma is characterized by multiple tumors, both spatially and temporally, which are found anywhere along the urinary tract, including the renal pelvis, ureter, bladder and urethra. The occurrence of multiple tumors at different sites in the renal pelvis/ureter is often associated with bladder cancer, either before or synchronous with the time of diagnosis. In fact, a previous history of bladder cancer is present in 10–20% of patients with UTUC, and 8.5–13% of patients with UTUC have synchronous bladder cancer according to previous reports.9-11 Even in patients with no history of bladder cancer, the onset (recurrence) of bladder cancer is common after surgical treatment of UTUC, occurring in 15–50% of cases mostly within 2 years after surgery.12, 13 Therefore, screening of the entire urinary tract is necessary when UTUC or bladder cancer is diagnosed.

The mechanisms of onset of bladder cancer concurrent with UTUC are thought to involve the downstream seeding of cancerous or cancer precursor cells from the upper tract or the effect of urinary mutagens to which the entire urinary tract is exposed. Investigations to determine the mechanisms are ongoing using approaches such as gene expression profiles, genetic mutation screening and microsatellite markers; however, the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated.14, 15

3. Diagnosis

The TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors has been widely used to stage UTUC. Physical, imaging and endoscopic examinations are used to evaluate T (the extent of primary tumor growth into the wall), N (regional LN) or M (distant metastasis). In addition, histological or cytological evidence must be available on diagnosis.

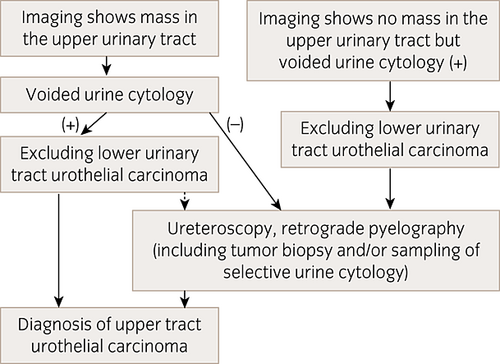

The diagnostic algorithm for UTUC is presented in Figure 1.

Diagnostic algorithm for UTUC. Dotted arrows indicate that ureteroscopy and retrograde pyelography can be selected.

(1) Imaging examinations

CTU

IVU, along with ultrasonography, has been the method of choice for detecting UTUC. However, the effectiveness of CTU has recently been reported. When the diagnostic power was compared between IVU and CTU, the detection capability of CTU (93.5–95.8% sensitivity, 94.8–100% specificity and 94.2–99.6% accuracy) was significantly greater than that of IVU (75.0–80.4% sensitivity, 81.0–86.0% specificity and 80.8–84.9% accuracy).16, 17 Another study has reported that the diagnostic capability of CTU is equivalent to that of RP.18 False negative CTU results can occur in the case of CIS or small (≤1 cm) masses, whereas false positive findings can be associated with benign tumors, chronic inflammation, hematomas or renal papillary hypertrophy. CTU has several advantages over IVU. For example, it provides images of urinary tract walls and outer views besides luminal aspects, allows easy identification of obstructions, even in a severe case of hydronephrosis, and also allows simultaneous cancer staging. Although it is dependent on patient body size, the CTU radiation dose is typically 15–35 mSv, which is significantly higher than the IVU radiation dose of 5–10 mSv.16 Hence, lowering the exposure is one of the challenges associated with CTU.

Staging of UTUC is also based on CT examination. Reports on the use of CT for cancer staging are scarce; however, the available data show a diagnostic accuracy of overall cancer staging of 87.8% using multidetector CT scanning.19 However, in staging of cT3, microscopic infiltration of the renal parenchyma (pT3a) is prone to false negative CT findings, whereas inflammatory alteration of surrounding adipose tissue tends to produce false positive results.19

MRI

The sensitivity of MRI examination for detecting UTUC is approximately 80% overall and 74% in small (<2 cm) tumors.20, 21 Accordingly, CTU is the preferred method in terms of diagnostic capabilities, and MRI serves as an alternative in patients who are unsuitable for CTU because of, for example, allergy to iodine contrast agents.20 However, attention should be paid to the fact that gadolinium-based contrast agents should not be administered to patients with GFR of 30 mL/min or less because of the risk of developing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.22

According to recent staging studies, utilizing diffusion-weighted MRI resulted in 70% accuracy for staging of ≤T2 and ≥T3 renal pelvic cancer, and 93% accuracy for staging of microscopic infiltration of the renal parenchyma (T3a) and macroscopic infiltration of the renal parenchyma or peripelvic fat (T3b).23 It is also worth noting that an apparent diffusion coefficient obtained from diffusion-weighted imaging correlates with tumor grade and the prognosis of UTUC.23, 24

(2) Urine cytology, retrograde pyelography and ureteroscopy

Urine cytology

A positive urine cytology finding in voided urine with a negative cystoscopy raises the suspicion of UTUC, particularly when biopsy results have excluded CIS of the bladder or prostate. However, urine cytology generally shows poor sensitivity and limited correlation with cancer staging in UTUC, even in high-grade cases, relative to bladder cancer.25

The cytology of catheterized renal pelvic/ureteral urine or urine obtained through ureteroscopy urine shows 40–70% sensitivity toward UTUC.26, 27 A high false negative rate of 50% was recorded in low-grade cancers,28 whereas a diagnostic accuracy of 75% was noted in high-grade cancers.29

RP

RP has a limited diagnostic value when diagnostic imaging, such as CT or MRI, is also carried out. Recent research regards RP, involving ureteral catheterization or ureteroscopy, merely as an optional test coinciding with selective urine cytology sampling.18 Nevertheless, RP can be worthwhile if the patient is contraindicated for CT or MRI because of allergy to contrast agents, or if there is any difficulty in inserting the ureteroscope.

Ureteroscopy

Ureteroscopy is valuable for the detection and definitive diagnosis of UTUC. However, ureteroscopic biopsy has relatively poor performance with regard to its positive predictive value for definitive cancer diagnosis and staging prediction. Guarnizo et al. investigated upper urinary tract lesions (n = 45) by ureteroscopic biopsy and diagnosed UTUC in 40 lesions.30 They found that 10 out of 22 cases (45%) staged as Ta by ureteroscopic biopsy had to be upstaged to ≥T1 in surgical specimens of RNU, and they concluded that ureteroscopic biopsy is not useful to predict cancer stages. In addition, Clements et al. carried out multivariate analysis of 238 cases that underwent preoperative ureteroscopic biopsy followed by RNU. Their results showed that the biopsy-based tumor grading significantly correlated with the tumor grade and with muscle-invasive cancer in surgical specimen of RNU, whereas the biopsy-based clinical staging had no correlation with these parameters.31

(3) Prediction of pathological stage by combined diagnostic tools

Imaging, urine cytology or ureteroscopic biopsy cannot produce accurate diagnosis or prognosis predictions of UTUC when used alone. Thus, recent studies have focused on the combined use of these techniques to obtain more accurate clinical staging and prognosis predictions. For example, a retrospective study of 659 cases of UTUC that underwent RNU revealed a preoperative nomogram covering three factors, namely grade (high grade vs low grade), architecture (sessile vs papillary) and location (renal pelvis vs ureter) of tumor, and achieved 76.6% accuracy in predicting non-organ-confined cancer.32 In another retrospective study of 274 cases of UTUC treated with RNU, an increased accuracy of predicting muscle-invasive or non-organ-confined cancer was observed for cases with high-grade tumor determined by either ureteroscopic biopsy or urine cytology when accompanied by local invasion on imaging.33 Similarly, another 172 cases of UTUC treated with RNU were retrospectively studied to evaluate preoperative variables as predictors of pathological stage. The study showed that the combination of the presence of hydronephrosis, high-grade status based on ureteroscopic biopsy and positive urine cytology was associated with muscle-invasive cancer in 89% of cases, and non-organ-confined cancer in 73% of cases when all three variables were positive. In contrast, no cases were detected as muscle-invasive or non-organ-confined cancer when all three variables were negative.34

Accordingly, the use of ureteroscopic biopsy along with imaging findings (clinical T stage and presence or absence of hydronephrosis) and urine cytology can significantly enhance the prediction of pathological stage and prognosis prediction; hence, it is expected that this combination will be useful in clinical decision-making. However, it should not be overlooked that this conclusion is entirely based on retrospective analyses of observational data; therefore, the aforementioned findings are yet to be externally validated. Further research is required to develop a reliable preoperative model for accurate prediction of pathological stage and prognostic prediction of cancer.

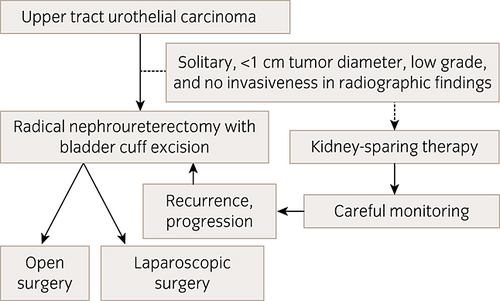

4. Surgical treatment

RNU is the gold standard surgical treatment for UTUC. However, as an open surgery technique, the procedure is not less invasive, because it often requires two incisions and increases the risk of developing postoperative chronic kidney disease, as renal function is reduced after RNU. Recent advances in endourology have shown that laparoscopic RNU can now be carried out safely, except for ≥T3 cases or for patients with suspected LN metastasis. In addition, further research is required to determine whether RNU should be carried out in all cases of low-grade, solitary or small cancer lesions.

Figure 2 shows the therapeutic algorithm for surgical treatment of UTUC.

Therapeutic algorithm for surgical treatment of UTUC. NB: Dotted arrows indicate that kidney-sparing therapy can be selected as an option.

(1) Radical nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff excision: Procedures and treatment outcomes

Outcomes of open versus laparoscopic surgery

It has been frequently reported that compared with open surgery, the amount of bleeding, postoperative pain and duration of hospitalization can be reduced by carrying out laparoscopic surgery. In their review of recurrence risks associated with open and laparoscopic surgeries, Eng et al. concluded that laparoscopic surgery was the gold standard for the treatment of organ-confined UTUC.35 Rassweiler et al. found no significant differences between open and laparoscopic surgeries with regard to bladder recurrence (24.0% vs 24.7%), local recurrence (4.4% vs 6.3%) and distant metastases (15.5% vs 15.2%) in their systematic review of nine comparative studies comparing the two procedures.36 In contrast, a small-scale, single-center, randomized comparative study showed that the 3-year CSS rate was higher and RFS duration was significantly longer with open surgery than with laparoscopic surgery in pT3 and high-grade cases.37 Laparoscopic surgery is yet to be thoroughly assessed with regard to its oncological effectiveness against non-organ-confined UTUC. Therefore, further larger-scale, randomized, comparative studies are required to reach a final conclusion about this topic.

Open surgery remains the primary treatment for UTUC, and it is recommended in ≥T3 cases or cases with suspected LN metastasis. Nevertheless, laparoscopic surgery is equally effective in ≤T2 cases in terms of long-term prognosis, and coupled with its low invasiveness, it can be a useful approach.

Significance of LN dissection

LN metastasis generally occurs in 30–40% of cases of UTUC, suggesting that proper management of LN metastasis likely leads to a better prognosis.38, 39

One of the important clinical roles of LND lies in its diagnostic value or depends on whether the procedure has an effect on prognostic stratification, including subsequent planning of adjuvant therapy. Existing data support the positive diagnostic significance; the prognosis was better in the pN0 group (pathologically negative LN metastasis) than in the pNx group (without LND), whereas a poor prognosis was noted in the pN+ group (pathologically positive LN metastasis).40, 41

With regard to therapeutic significance, conclusive evidence is yet to be presented, although, to date, a number of reports have shown that LND is associated with improving prognosis in ≥pT2 cases. According to a study of 1453 cases from 13 institutions, survival rates did not differ significantly between the LND group and the no LND group. Focusing on pN0 cases, however, a significantly better prognosis was observed in cases where eight or more LN were removed than in those where fewer than eight LN were removed, indicating the impact of the extent of LND on prognosis.42 Another multicenter study involving 785 cases of local invasive cancer that underwent LND showed that compared with the pNx group, the risks of recurrence and cancer death were reduced in the pN0 group.43 In contrast, a population-based study of 2824 cases detected no significant differences in CSS rates between the pN0 and pNx groups, and concluded that LND has no therapeutic significance.44

In summary, there is still a lack of convincing evidence to support the therapeutic significance of LND. Matters that need to be addressed include the fact that the extent of LND has not been standardized, and that its superiority is yet to be shown through randomized studies. More detailed analyses are warranted for establishing the therapeutic significance of LND in muscle-invasive UTUC.

Types of distal ureter and its orifice excision

RNU involves excision of the distal ureter, including its intramural segment, along with the surrounding bladder wall. Several techniques are available for this purpose.

Extravesical approaches include resection through an incision in the bladder wall made near the ureteral orifice,45 resection by clipping without bladder wall incision46 and resection by stapling.47 The transvesical approach is carried out after cystotomy, and the confirmation of the ureteral orifice through the bladder by incising the adjacent bladder mucosa through the full thickness of the bladder.48 Although this approach allows complete removal of the intramural ureter, it is not only relatively invasive, but also prone to tumor spillage. The endoscopic approach is also known as the pluck technique, and involves a transurethral incision from the bladder mucosa around the ureteral orifice through the full thickness of the bladder.49 Various modifications to the pluck method have been described, including the use of laparoscopic forceps50 and the uncommon “stripping” technique wherein only the distal ureter is transurethrally removed after deliberate intussusception.51 These methods are relatively non-invasive; however, they are also susceptible to tumor spillage.

No prospective studies have been carried out to directly compare oncological outcome and invasiveness between each of the aforementioned techniques. Nearly all existing reports are retrospective, involving a limited number of samples, and none has identified a significant difference between the techniques. One exception is the recent large-scale, multicenter, retrospective study involving 2681 cases.46 Although the OS rates, CSS rates and RFS rates excluding intravesical recurrence were not significantly different between the techniques, intravesical recurrence was significantly higher for the endoscopic approach than for the transvesical or extravesical approach (5-year intravesical RFS rates were 40%, 71% and 64%, respectively).

Treatment of pure CIS of the upper urinary tract

There have been an extremely limited number of reports on treatment outcomes regarding pure CIS of the upper urinary tract. Karam et al. retrospectively assessed 1363 cases treated with RNU between 1987 and 2007, and reported the clinical outcome of 28 cases (2%) with pure CIS of the upper urinary tract. They reported favorable findings, such as a 3-year RFS rate of 84%, 3-year CSS rate of 89% and just three cases of cancer death with a median observation time of 42.8 months.52 In contrast, a separate study involving pure CIS of upper urinary tract cases showed no significant difference in long-term oncological outcome between RNU and BCG instillation into the upper urinary tract.53

Effectiveness of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy

The only prospective trial on perioperative chemotherapy of RNU was carried out by Bamias et al. The phase II study showed that the use of paclitaxel and carboplatin as an adjuvant chemotherapy was effective in reducing the risk of distant metastasis in patients with ≥pT3 or pN+ UTUC.54 Another study reported a reduction in intravesical recurrence in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy after RNU.55 In contrast, one retrospective study showed that adjuvant chemotherapy did not lead to improved prognosis.56

No definitive evidence exists regarding whether perioperative chemotherapy should be initiated preoperatively (neoadjuvant setting) or postoperatively (adjuvant setting). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy might have survival benefit for UTUC, because strong evidence supports that neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves the long-term prognosis in cases of invasive bladder cancer with a same histological type of urothelial carcinoma. Furthermore, other advantages in the neoadjuvant setting for UTUC include the availability of cisplatin-based chemotherapy before renal impairment caused by RNU, and the possibility of assessment for the effect in RNU specimens, which could provide prognostic information.57 Possible disadvantages include the likelihood of unnecessarily administering chemotherapy to patients whose prognosis would have been favorable anyway, as well as prolongation of the preoperative phase.

The key parameter that affects treatment outcomes of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is pathological CR rate. In fact, pathological CR rates were reported to be approximately 13–15%, with adequate long-term prognosis being observed in most pathological CR cases.58, 59

Postoperative follow up after RNU

Local recurrence or distant metastasis occurs in approximately 25% of patients treated with RNU.60, 61 Periodic CT examination is essential for monitoring the occurrence of local recurrence and distant metastasis. Unfortunately, no evidence-based follow-up schedule exists for UTUC. Ideally, each patient should undergo periodic cystoscopy and urine cytology, considering the relatively high intravesical recurrence rate of 15–50%.62

Increased efforts should be directed toward the development of an evidence-based follow-up schedule in the near future, covering not only prognostic factors, such as recurrence and survival rates, but also health economics aspects.

(2) Prognostic factors for local recurrence, distal metastasis and intravesical recurrence after radical nephroureterectomy

Prognostic factors for local recurrence and distant metastasis

Previous studies reported that postoperative local recurrence or distant metastasis occurred in 24–28% of patients treated with RNU.60, 61 In these reports, intravesical recurrence was not included in these local recurrence cases. The first occurrence of local recurrence or distant metastasis was noted within 10–12 months postoperatively on average, and most of them were found within 3 years postoperatively.60, 61 Meanwhile, various reports have described possible risk factors for poor prognosis of UTUC. They can be largely divided into three categories: patient background factors, histopathological factors and surgical technique-related factors.

(a) Patient background factors

Patient background factors that have been suggested to affect prognosis include age,63 sex,64 initial symptoms,65 history of smoking,66 tumor location,67, 68 clinical T stage,69 biopsy tumor grade70 and presence or absence of hydronephrosis.69, 71 With regard to tumor location, retrospective analysis of accumulated data that was carried out as a multicenter study in France showed a significantly poorer prognosis in solitary ureteral cancer than in solitary renal pelvic cancer, whereas multiple tumors were analyzed separately.67 In contrast, the results of an international, multicenter, retrospective review of accumulated data showed no clear difference in prognosis between ureteral and renal pelvic cancers.68

Risk classification by patient background factors is expected to help in the decision-making process when selecting surgical techniques, in determining whether to carry out LND and to what extent, and in determining whether to carry out neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

(b) Histopathological factors

Histopathological factors that have been reported to be of prognostic value include the pathological T stage,60, 72, 73 tumor grade,74 presence or absence of LN metastasis,75 presence or absence of concurrent CIS,76 presence or absence of LVI,77, 78 multiplicity79 and tumor diameter.80 Of these, the pathological T stage is the most promising possible prognostic factor. For example, the documented 5-year RFS rates are 88.0%, 71.4%, 48.0% and 4.7%, and 5-year CSS rates are 92.1–97.8%, 74.7–84.1%, 54.0–56.3% and 0–12.2% in pTa-1, pT2, pT3, and pT4 cancers, respectively.60, 72, 73 Several other studies have shown the usefulness of the subclassification of pT3 tumor as a prognostic factor.81, 82 In addition, reports have shown that the presence or absence of LVI in a tumor specimen is a critical prognostic factor, and the status of LVI can be an independent prognostic factor in UTUC without LN metastasis.77, 78

Taken together, risk assessment derived from histopathological factors is likely to provide appropriate guidance for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy selection, as well as for establishing appropriate postoperative follow-up protocols.

(c) Surgical technique-related factors

Differences in surgical techniques can also affect prognosis, such as technical approach for the treatment of a primary tumor (open or laparoscopic)37, 83 or the type of bladder cuff excision46 and extent of LND.39, 84

A prognostic nomogram for the prediction of recurrence/metastasis and survival rates has been developed on the basis of a combination of multiple risk factors through large-scale, retrospective analysis of accumulated data.85 Prognostic nomograms are considered to be useful for more accurate prognostic predictions, and have a certain impact on treatment planning. However, in terms of daily clinical practice, their effectiveness has not been formally validated.

Prognostic factors for intravesical recurrence

After RNU, intravesical recurrence generally occurs in approximately 15–50% of cases, most of which occur within approximately 2 years postoperatively.62

Clinicopathological factors that have been reported as prognostic factors for intravesical recurrence include the number of tumors,12, 86, 87 tumor diameter,86, 88, 89 pathological T stage,86, 87 sex,90, 91 history of bladder cancer,88 tumor location,91 tumor grade62 and renal function.12 Among these, multiple or large-diameter tumors were found to be risk factors by several studies; thus, they are considered to be fairly reliable prognostic factors for intravesical recurrence. Many studies have also used multivariate analysis to assess the association between intravesical recurrence and surgical techniques of RNU. However, with a few exceptions, the technical approach (open or laparoscopic)36, 92 and type of bladder cuff excision48, 50 were reported to have no significant effect on intravesical recurrence.

Recently, several researchers began to report the preventive effect of a single dose of an anticancer agent on intravesical recurrence immediately after RNU. In a randomized, multicenter study (n = 284) in the UK, intravesical recurrence was significantly reduced in patients who received a single intravesical instillation of mitomycin C just before the removal of the urethral catheter (approximately 1 week postoperatively) than in patients in the control group who received no instillation of anticancer drug.93 In line with this, a Japanese, randomized, multicenter trial (n = 77) showed a significant reduction of intravesical recurrence in patients who received a single intravesical instillation of pirarubicin within 48 h postoperatively than in control patients who received no anticancer drug.94 These data strongly indicate the preventive value of postoperative single intravesical instillation of an anticancer drug on intravesical recurrence. More thorough data are required on the optimal method of dosing and safety of this novel approach to establish its utility in clinical settings.

(3) Kidney-sparing surgery and the treatment outcomes

Kidney-sparing surgery is enabled by endoscopic therapy via ureteroscope or percutaneous pyeloscopy, or partial ureterectomy; however, these techniques have not been directly compared with RNU in randomized clinical trials. The primary aim of carrying out kidney-sparing surgery is to maintain renal function and avoid the need for hemodialysis in cases of UTUC in a solitary kidney or bilateral UTUC, those with impaired renal function, or those with poor PS. Ureteroscopic or percutaneous kidney-sparing surgery has been carried out in cases of small, low-grade and low-stage tumors even in the presence of a healthy contralateral kidney, and has produced favorable treatment outcomes.95

Endoscopic therapy via ureteroscope typically involves the use of a holmium:YAG or neodymium:YAG laser that coagulates and vaporizes the tumor. The results of ureteroscopic kidney-sparing therapy carried out on low-grade, low-stage UTUC showed 13–54% 5-year RFS rates, and 10–33% of cases subsequently underwent RNU. Factors that were associated with recurrence were the tumor grade, presence or absence of multicentric tumors, tumor diameter and presence or absence of a history of bladder cancer.96-99 It is also important to fully inform the patient preoperatively of the need for strict postoperative monitoring.

The percutaneous approach using pyeloscopy is selected for tumors affecting the renal pelvis, calyx or proximal ureter that are hard to reach using a ureteroscope. To date, this technique has yielded positive outcomes. For example, Palou et al. treated 34 cases of renal pelvic or proximal ureteral cancers by this technique and noted a recurrence rate of 41.2% during the 51-month follow-up period, while achieving a kidney preservation rate of 73.5%.100 However, recent advances and the development of small-diameter flexible ureteroscopes have resulted in a decline in the percutaneous approach using pyeloscopy.

Partial ureterectomy and ureterovesiconeostomy are applicable as kidney-sparing therapies for distal ureteral tumor. The Boari flap or Psoas hitch technique is available when the residual ureter is well-separated from the bladder. These approaches are considered for non-invasive solitary tumors located in the distal one-third of the ureter, and require confirmed absence of tumors in the renal pelvis/proximal ureter.

5. Systemic chemotherapy and others

Systemic chemotherapy for metastatic upper tract urothelial carcinoma

For metastatic or recurrent bladder cancer, GC or MVAC combination therapy is administered as a scientifically validated regimen. Unfortunately, no chemotherapy has been properly validated for therapeutic effectiveness especially focusing on metastatic or recurrent UTUC. Thus, at present, chemotherapy regimens used for UTUC are indeed the same as those originally established for bladder cancer treatment, based on the notion that both cancers are a form of urothelial carcinoma. Meanwhile, Tanji et al. administered GC therapy consisting of at least two courses to 71 cases of metastatic urothelial carcinoma, including UTUC.101 According to their results, response rates in renal pelvic, ureteral, and bladder cancers were 35% (6/17), 43% (9/21) and 50% (16/32), respectively, among patients with no prior chemotherapy or those with recurrence of more than 6 months after first chemotherapy. Further evidence is required to justify the administration of bladder cancer regimens in cases of UTUC, because treatment sensitivity can be variable between bladder cancer and UTUC, even if both are the same histological type of urothelial carcinomas.102 Furthermore, most patients with metastatic or recurrent UTUC have impaired renal function, which results from RNU.103 In cases of impaired renal function, dose reduction of cisplatin-based chemotherapy is generally required, which might reduce its efficacy in UTUC. It should also be mentioned that there are no validated second- or third-line chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of UTUC, although the same is true in the case of bladder cancer.

Recently, Tanaka et al. reported the prognosis of 132 patients with metastatic or recurrent UTUC after RNU and who underwent systemic chemotherapy including MVAC or GC. Their multivariate analysis showed three independent factors that significantly affected both CSS and OS: PS (0–1 vs 2–4) at the initiation of chemotherapy, presence or absence of liver metastasis and the number of recurrence or metastatic sites (1 vs ≥2).104

Chemotherapy in patients with impaired renal function

To date, no standard chemotherapy regimens are available for UTUC patients with renal impairment. Although the use of carboplatin-based, non-platinum chemotherapy has been reported, its efficacy remains to be validated.

On consideration of perioperative chemotherapy in patients treated with RNU, adjuvant chemotherapy is indicated in only a limited number of cases, because renal impairment is inevitable after RNU. Lane et al. retrospectively investigated 336 cases of UTUC treated with RNU, and assessed the association between renal function preoperatively and postoperatively, and the proportion of patients who were eligible to receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy.103 Patients with eGFR of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were regarded as having chronic kidney disease and as ineligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The results showed that 48% of the patients were indicated for chemotherapy before RNU; however, this number significantly declined to 22% postoperatively. The authors suggested cisplatin-based chemotherapy should be carried out as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients treated with RNU.

Although very few studies have examined the effect of cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy after RNU on renal function, rare cases of hemodialysis have been reported.105

Instillation of BCG or anticancer drug into the upper urinary tract

Instillation of BCG into the upper urinary tract has been used for cases of pure CIS of the upper urinary tract in solitary kidney or bilateral cases, those with impaired renal function or those with poor PS to preserve renal function.106 Instillation of BCG into the upper urinary tract can be anterograde through a percutaneous nephrostomy tube, retrograde through a ureteral catheter or through an indwelling double-J stent; however, the method of choice is yet to be established. In addition, instillation of BCG has been evaluated only in small-scale, retrospective studies; thus, there is no consensus on procedural details, such as the BCG dose, dosing concentration, dosing duration and frequency of instillation. Giannarini et al. described clinical outcomes of BCG perfusion through percutaneous nephrostomy tube in 42 cases of pure CIS of the upper urinary tract.106 This resulted in 40% recurrence and 5% progression, with a mean observation period of 42 months.

Only a few attempts have been made to assess the preventive effect for recurrence by adjuvant instillation of BCG or anticancer drugs into the upper urinary tract after endoscopic resection. Therefore, no conclusions have been drawn on the efficacy of such approaches.107-109

Radiation therapy

The efficacy of radiation therapy for UTUC has been evaluated in a limited number of retrospective studies as adjuvant therapy to RNU. Unfortunately, their findings are inconsistent, with some studies showing the survival benefit resulting from postoperative irradiation with or without cisplatin-based chemotherapy, whereas other equivalent studies show no survival benefit.110-113

Conflict of interest

None declared.