Effect of a care-coordinated responsive parenting intervention on obesogenic risk behaviours among mother–infant dyads enrolled in WIC

Summary

Background

Integrating health care and social care presents opportunities to deliver responsive parenting (RP) interventions for childhood obesity prevention.

Objectives

This analysis examined the effect of an integrated RP intervention on infant obesogenic risk behaviours.

Methods

This secondary analysis included 228 mother–infant dyads in the Women, Infants, and Children Enhancements to Early Healthy Lifestyles for Baby (WEE Baby) Care study, a pragmatic randomized clinical trial that integrated care between paediatric clinicians and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) nutritionists to encourage RP. Mothers were randomized to a 6-month RP intervention or standard care. The Early Healthy Lifestyle risk assessment tool was completed at infant ages 2 and 6 months. Logistic regression examined study group effects on obesogenic risk behaviours, while t-tests assessed study group effects on a total obesogenic risk behaviour score. Models adjusted for milk type and parity.

Results

RP mothers were less likely to report nighttime feedings at 2 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.21, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.07–0.62) and 6 months (aOR 0.36, 95% CI 0.16–0.81); pressure to finish the bottle (aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30–0.93) and using screens when feeding/playing at 2 months (aOR 0.34, 95% CI 0.17–0.67); and putting their infant to bed after 8:00 PM at 6 months (aOR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21–0.97). RP mothers had significantly lower obesogenic risk behaviour scores at 2 months (p = 0.009) but not at 6 months (p = 0.06) compared to standard care.

Conclusions

The WEE Baby Care intervention decreased some obesogenic risk behaviours among WIC mother–infant dyads. Integrated care in health and social settings can be used to provide patient-centred RP guidance to improve early obesogenic risk behaviours in high-risk populations.

Abbreviations

-

- AAP

-

- American Academy of Paediatrics

-

- aOR

-

- adjusted odds ratio

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- EHL

-

- Early Healthy Lifestyle

-

- HALF

-

- Healthy Active Living for Families

-

- INSIGHT

-

- Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- REDCap

-

- Research Electronic Data Capture

-

- RP

-

- responsive parenting

-

- SD

-

- standard deviation

-

- SNAP-Ed

-

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education

-

- TV

-

- television

-

- WEE Baby

-

- Women, Infants, and Children Enhancements to Early Healthy Lifestyles for Baby

-

- WIC

-

- the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

1 INTRODUCTION

Obesity affects one in five children in the United States.1 Excess weight gain in infancy increases the risk of obesity and obesity-related comorbidities in later life.2, 3 Responsive parenting (RP) interventions that encourage developmentally appropriate, prompt and contingent parenting responses to infants' needs4 have improved child weight outcomes.5, 6 RP messaging has also improved parent feeding practices,7, 8 dietary intake,9 infant sleep,10 tummy time and reduced screen exposure,11 and other modifiable obesogenic risk factors.12 RP interventions delivered using the home-visiting model show promise in reducing these risks and promoting a healthy weight trajectory.5, 6 Social care settings, particularly the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), offer another opportunity for implementing RP interventions, as nearly half of U.S. children are eligible.13 Leveraging these established systems may offer a more sustainable, affordable and scalable approach to implementing pragmatic interventions that evaluate the real-world effectiveness of RP strategies in early childhood obesity prevention.

Children qualifying for government programmes such as WIC and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) may receive care in both health care and social care settings.14 However, coordinated care between settings is lacking,15 which can result in inconsistent prevention messaging that leads to inefficiencies in obesity prevention messaging and strategies.16 For example, WIC mothers reported receiving conflicting messaging and guidance on parenting and feeding from paediatric clinicians and WIC nutritionists.17 Dietz et al. proposed a clinical-community integrated framework,18 which emphasizes fostering partnerships and collaboration between health care (e.g., paediatric clinics) and social care (e.g., WIC programmes) settings to integrate and coordinate care to optimize strategies for the prevention of childhood obesity to advance health equity.19 Since integration and care coordination between health care and social care settings may hold promise in the collective effort to address childhood obesity,20 it may also offer opportunities to deliver RP messaging between settings.

To address these gaps, the Women, Infants, and Children Enhancements to Early Healthy Lifestyles for Baby (WEE Baby) Care study, a pragmatic randomized clinical trial tested the integration of health (paediatric clinicians) and social (WIC nutritionists) care delivery. The trial was effective at promoting responsive parenting and reducing infant body mass index (BMI).21 This secondary analysis aims to examine the effects of the WEE Baby Care RP intervention on obesogenic risk behaviours during early infancy among mother–infant dyads enrolled in WIC. We hypothesized that mothers in the RP intervention would be less likely to use obesogenic risk behaviours compared to mothers in standard care.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and participants

This is an analysis of secondary data from the WEE Baby Care study. Detailed information regarding the study design has been published.22 Briefly, mothers and their newborn infants were recruited between July 2016 and May 2018 from Geisinger in northeastern Pennsylvania. Mothers were eligible if they were ≥18 years with a full-term (≥37 weeks) singleton delivery, planned to attend well-child visits at a participating Geisinger clinic, were English-speaking, and enrolled in WIC. Mother–infant dyads were excluded if the infant weighed <2500 g at birth, the mother anticipated transferring to a non-participating paediatric clinic within the next 9 months or lived outside the service area of a participating WIC clinic, or either the mother or infant had a medical condition that would impact participation (e.g., feeding disorder). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Geisinger (IRB #03692) and The Pennsylvania State University (IRB #2015–0554) and is registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03482908).

2.2 Responsive parenting intervention

Mother–infant dyads were randomized to either a 6-month WEE Baby Care RP intervention (n = 131) or standard care (n = 157). Both groups were encouraged to attend standard well-child visits with paediatric clinicians at infant ages 3–5 days (newborn) and at ages 1, 2, 4 and 6 months, and attend standard visits with WIC nutritionists between birth to 2, 2–4 and 4–6 months.21 The RP intervention utilized advanced health information technology to integrate data, enabling care coordination between paediatric clinicians and WIC nutritionists to deliver personalized, responsive parenting messages.23 The RP intervention included: (1) RP curriculum training for paediatric clinicians and WIC nutritionists and RP curriculum delivered by WIC nutritionists during regularly scheduled visits, (2) a patient-reported outcome measure, the Early Healthy Lifestyles (EHL) risk assessment tool, offered to mothers before each well-child visit and (3) data integration to inform counselling and care coordination between paediatric clinicians and WIC nutritionists. RP intervention messaging included guidance related to infant feeding, soothing, sleep and interactive play, which was informed by the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) Healthy Active Living for Families (HALF) curriculum24 and selected messages from the Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) study.5, 25 Participants in the RP intervention group received RP messages through: (1) mailed handouts following randomization; (2) from paediatric clinicians at each well-child visit and (3) from WIC nutritionists with discussion on study team-developed education topics during scheduled visits up to infant age approximately 6 months, the last visit of this study.22 For the mailed curriculum, participants received a welcome packet specific to their randomized groups that included information about what to expect in the first few days with their newborn directly following randomization. The RP intervention group also received a comprehensive packet with RP curriculum that included anticipatory guidance arranged by development from birth to 8 months (Table 1). Additionally, WIC nutritionists disseminated and discussed the same RP curriculum at infant intake, 3 and 6 months WIC visits.

| WEE Baby Care RP content | Welcome packet | 0–3 Month packet | 4–6 Month packet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding | |||

| Baby's belly/stomach size | X | ||

| Hunger and fullness cues | X | X | X |

| Bottle feeding practices | X | X | X |

| Fruit juice/sugar-sweetened beverages | X | X | X |

| Timing of the introduction of solids | X | ||

| Repeated exposure | X | X | |

| Shared responsibility of feeding | X | ||

| Food and beverages to offer and avoid | X | ||

| Portion size of solid foods | X | ||

| Emotion regulation/soothe | |||

| Reasons for crying, not just hunger | X | ||

| Soothing strategies | X | X | |

| Temperament | X | ||

| Crying norms | X | ||

| Sleep | |||

| Recommended amount of sleep | X | X | X |

| Safe sleep | X | X | X |

| Goal to put baby to bed drowsy but awake | X | X | X |

| Early bedtime is best | X | ||

| Establishing a consistent bedtime routine | X | X | |

| Turn the TV off at bedtime | X | ||

| How to handle night wakings, calming baby at night | X | X | |

| Naptime routine | X | ||

| Interactive play | |||

| Tummy time | X | X | |

| Limit time in restrictive equipment (swing, seat, etc.) | X | X | X |

| Ways to play with your baby | X | X | X |

| Supporting motor milestones and social skills | X | ||

| Redirecting baby's attention to stop unwanted behaviours | X | ||

- Abbreviation: WEE Baby, Women, Infants, and Children Enhancements to Early Healthy Lifestyles for Baby.

3 MEASURES

3.1 Sociodemographic characteristics

Maternal sociodemographic characteristics included self-reported annual household income, parity, marital status, race, ethnicity, education level and age. Child characteristics, obtained from patient electronic health records at enrollment, included infant sex, gestational age, date of birth, birth weight and birth length.

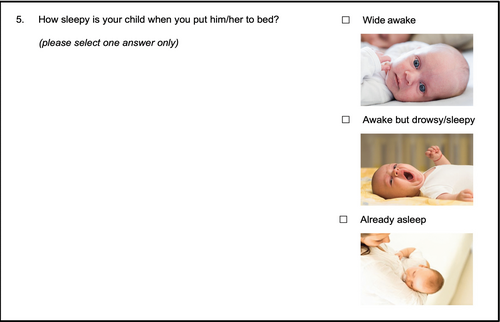

3.2 EHL risk assessment tool

The study team developed the 15-item patient-reported EHL risk assessment tool (see Table S1), a patient-reported outcome measure, based on the Infant Feeding Practices Study II,26, 27 the INSIGHT study5, 25 and the HALF curriculum.24 Two items assessed obesogenic behaviours related to infant diet, five items assessed feeding practices, four items assessed infant sleep, two items assessed parent–child interactive play, one item assessed appetitive traits and one item assessed the caregiver's relationship to the infant. The EHL risk assessment tool addresses lower health literacy and numeracy skills with the use of images and white space (Figure 1) and can be completed in ~2 min. The EHL risk assessment tool was completed when infants were approximately ages 2 and 6 months. These time periods represent critical developmental windows where rapid changes occur in various areas like dietary intake, motor skills, cognitive abilities, social–emotional interaction and language development.28-30 Mothers in the RP intervention completed EHL risk assessment tool in the electronic health record patient portal or in the waiting room on a tablet prior to their clinic visit. Responses were immediately available in the infant's electronic health record to facilitate tailored preventative counselling by paediatric clinicians. The EHL risk assessment tool, clinical counselling and vital signs were securely shared with WIC nutritionists. Subsequently, WIC nutritionists discussed RP messaging tailored to obesogenic behaviours reported on the EHL risk assessment tool. The standard care group completed the EHL risk assessment tool online via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) or paper questionnaires. These data were not integrated into the infant's electronic health record or used to facilitate tailored preventive counselling by paediatric clinicians or WIC nutritionists. Mothers who did not complete the EHL risk assessment tool at either time point (n = 60) were excluded from the current analysis, resulting in an analytic sample of 228 mother–infant dyads.

3.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including means and standard deviations (SD) as well as frequencies and percentages summarized the main study variables. T-tests and χ2 tests tested study group effects on continuous and categorical sociodemographic variables, respectively. Twelve items on the EHL risk assessment tool were categorized as binary variables including: developmentally inappropriate bottle sizes (defined as either <3 or ≥5 oz. at 2 months; defined as either <5 or >8 oz. at 6 months),24 food to soothe, pressure to finish the bottle, nighttime feeding, using screens when feeding/playing, putting their infant to bed after 8:00 PM,10 frequent night wakes (wakes ≥2 times per night),31 having the television (TV) on in the room where the infant sleeps, putting their infant to bed already asleep instead of drowsy but awake,10 limited active play or tummy time (none or once per day),24 and using cellphone or TV while playing (sometimes or more often),24 and perceiving their infant always being hungry. Several items on the EHL risk assessment tool were not considered in this analysis due to the low frequency of reported use among parents of infants less than 6 months of age including: feeding beverages other than breastmilk or infant formula, feeding energy-dense processed foods and perceiving their infant does not eat enough, eats too much, spits out food or is a picky eater. One item on the EHL risk assessment tool, perceiving their infant eats the right amount, was excluded because it is highly correlated with perceiving their infant always being hungry (r = −0.76, p < 0.0001). Logistic regression models examined study group effects for binary variables on the EHL risk assessment tool at infant ages 2 and 6 months. At each time point, we analysed 12 obesogenic risk behaviours (i.e., feeding practices, infant sleep, parent–child interactive play and infant appetitive traits), before and after adjusting for covariates. Covariates included milk type (any breastmilk vs. exclusive infant formula) and parity (first child vs. not), factors that impact child weight.32 Lastly, we created a composite score for these 12 obesogenic risk behaviours, scores ranging from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater use of obesogenic risk behaviours by parents. T-tests were conducted to test the impact of the study group (RP intervention vs. standard care) on the total obesogenic risk behaviour scores at infant ages 2 and 6 months. Cohen's d was calculated to determine the effect size of group differences. Moderation analyses examined whether the effect of the study group on any obesogenic risk behaviour or the total obesogenic risk behaviour scores varied by milk type (any breastmilk vs. exclusive infant formula) and parity. Data were analysed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

4 RESULTS

4.1 Participant characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics of mother–infant dyads are described in Table 2. About half of infants were male, and the mean gestational age was 39.6 weeks. The majority of mothers were white (65.2%), non-Hispanic (74.8%) and had annual household incomes <$25 000 (63.7%). A total of 27.6% of the infants in this study were firstborns. Sociodemographic characteristics did not significantly differ by study group. Exclusive infant formula feeding rates increased from 65.6% at 2 months to 78.4% at 6 months, whereas any breastfeeding decreased from 34.5% at 2 months to 21.6% at 6 months.

| Total sample (n = 228) | RP intervention (n = 93) | Standard care (n = 135) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant | |||

| Male, no. (%) | 118 (51.8) | 49 (52.7) | 69 (51.1) |

| Gestational age, mean (SD) (weeks) | 39.6 (1.1) | 39.7 (1.1) | 39.5 (1.2) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD) (kg) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.5) |

| Birth length, mean (SD) (cm) | 49.5 (2.3) | 49.3 (2.2) | 49.6 (2.4) |

| Mother | |||

| Age, mean (SD) (years) | 27.5 (5.4) | 27.8 (5.5) | 27.3 (5.3) |

| Parity, first child, no. (%) | 63 (27.6) | 27 (29.0) | 36 (26.7) |

| Race, no. (%) | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) |

| Asian | 3 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.5) |

| Black or African American | 32 (14.1) | 15 (16.3) | 17 (12.6) |

| White | 148 (65.2) | 62 (67.4) | 86 (63.7) |

| Othera | 42 (18.5) | 14 (15.2) | 28 (20.7) |

| Hispanic, no. (%) | 54 (25.2) | 19 (21.8) | 35 (27.6) |

| Marital status, no. (%) | |||

| Married/living with partner | 113 (52.8) | 45 (51.7) | 68 (53.5) |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 101 (47.2) | 42 (48.3) | 59 (46.5) |

| Annual household income, no. (%) | |||

| <$10 000 | 50 (25.3) | 16 (19.3) | 34 (29.6) |

| $10 000–$24 999 | 76 (38.4) | 39 (47.0) | 37 (32.2) |

| $25 000–$49 999 | 66 (33.3) | 26 (31.3) | 40 (34.8) |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 6 (3.0) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (3.5) |

| Education, no. (%) | |||

| Some high school or less | 22 (10.3) | 7 (8.1) | 15 (11.8) |

| High school graduate | 112 (52.3) | 45 (51.7) | 67 (52.8) |

| Some college | 61 (28.5) | 27 (31.0) | 34 (26.8) |

| College graduate or more | 19 (8.9) | 8 (9.2) | 11 (8.7) |

- Note: No statistically significant study group differences for any sociodemographic characteristic at p < 0.05 (t-test compared mean (SD) and chi-squared compared n [%]).

- Abbreviations: RP, responsive parenting; SD, standard deviation.

- a Participants self-reported as Puerto Rican, Mexican and multiracial.

4.2 Study group effects on the Early Healthy Lifestyle risk assessment tool

4.2.1 Mothers' feeding practices

As shown in Table 3, at 2 months, mothers in the RP intervention were less likely to pressure to finish the bottle (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.53, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.30–0.93), to report nighttime feedings (aOR 0.21, 95% CI 0.07–0.62), and to use screens when feeding/playing with their infant (aOR 0.34, 95% CI 0.17–0.67) compared to standard care. At 6 months, mothers in the RP intervention were also less likely to report nighttime feedings (aOR 0.36, 95% CI 0.16–0.81) compared to standard care. There were no study group effects on the use of developmentally inappropriate bottle sizes or food to soothe.

| RP Intervention (n = 93), % | Standard carea (n = 135), % | OR (95% CI) | aORb (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers' feeding practices | ||||

| Developmentally inappropriate bottle size | ||||

| 2 months | 50.7 | 47.8 | 1.12 (0.63, 2.01) | 1.15 (0.63, 2.10) |

| 6 months | 19.6 | 15.5 | 1.33 (0.55, 3.25) | 1.65 (0.63, 4.33) |

| Food to soothe | ||||

| 2 months | 36.6 | 34.9 | 1.08 (0.60, 1.92) | 1.07 (0.59, 1.94) |

| 6 months | 33.3 | 38.5 | 0.80 (0.40, 1.60) | 0.81 (0.40, 1.64) |

| Pressure to finish the bottle | ||||

| 2 months | 45.1 | 60.3 | 0.54 (0.31, 0.95) | 0.53 (0.30, 0.93) |

| 6 months | 45.1 | 59.8 | 0.55 (0.28, 1.07) | 0.53 (0.27, 1.04) |

| Nighttime feeding | ||||

| 2 months | 81.7 | 95.5 | 0.21 (0.07, 0.61) | 0.21 (0.07, 0.62) |

| 6 months | 64.7 | 83.9 | 0.35 (0.16, 0.79) | 0.36 (0.16, 0.81) |

| Use of screens when feeding or playing | ||||

| 2 months | 17.1 | 37.0 | 0.35 (0.18, 0.69) | 0.34 (0.17, 0.67) |

| 6 months | 17.7 | 20.5 | 0.83 (0.36, 1.94) | 0.83 (0.35, 1.96) |

| Infant sleep | ||||

| Put to bed after 8:00 PM | ||||

| 2 months | 82.9 | 79.4 | 1.26 (0.62, 2.59) | 1.27 (0.62, 2.62) |

| 6 months | 66.7 | 81.7 | 0.45 (0.21, 0.95) | 0.46 (0.21, 0.97) |

| Frequent night wakes | ||||

| 2 months | 42.7 | 52.8 | 0.67 (0.38, 1.17) | 0.66 (0.37, 1.18) |

| 6 months | 31.4 | 37.6 | 0.76 (0.38, 1.53) | 0.79 (0.38, 1.61) |

| TV on in room when sleeping | ||||

| 2 months | 28.1 | 40.9 | 0.56 (0.31, 1.02) | 0.57 (0.31, 1.03) |

| 6 months | 31.4 | 29.9 | 1.07 (0.53, 2.18) | 1.10 (0.54, 2.24) |

| Put bed already asleep | ||||

| 2 months | 29.3 | 43.2 | 0.54 (0.30, 0.98) | 0.55 (0.30, 1.00) |

| 6 months | 13.7 | 23.1 | 0.53 (0.21, 1.31) | 0.52 (0.21, 1.30) |

| Interactive play | ||||

| Limited active play or tummy time | ||||

| 2 months | 24.4 | 22.8 | 1.09 (0.57, 2.09) | 1.06 (0.55, 2.05) |

| 6 months | 2.0 | 3.5 | 0.56 (0.06, 5.14) | 0.73 (0.07, 7.28) |

| Use of cellphone or TV while playing | ||||

| 2 months | 32.9 | 42.1 | 0.68 (0.38, 1.21) | 0.66 (0.37, 1.18) |

| 6 months | 29.4 | 40.2 | 0.62 (0.31, 1.26) | 0.64 (0.31, 1.33) |

| Appetitive traits | ||||

| Infant always hungry | ||||

| 2 months | 17.1 | 21.3 | 0.76 (0.37, 1.56) | 0.76 (0.37, 1.56) |

| 6 months | 5.9 | 12.0 | 0.46 (0.13, 1.68) | 0.46 (0.13, 1.69) |

- Note: Significant results are bolded for emphasis. Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; RP, responsive parenting.

- a Reference group for all models is standard care.

- b Adjusted for milk type and parity.

4.2.2 Infant sleep

As shown in Table 3, at 2 months, mothers in the RP intervention were more likely to put their infant to bed drowsy but awake (odds ratio [OR] 0.54, 95% CI 0.30–0.98) compared to standard care, but this effect was no longer significant in an adjusted model. At 6 months, mothers in the RP intervention were less likely to put their infant to bed after 8:00 PM (aOR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21–0.97) compared to standard care. There were no study group effects on frequent night wakes or having the TV on in the room where the infant sleeps.

4.2.3 Infant interactive play

As shown in Table 3, there were no study group effects on limited active play or tummy time, or the use of cellphone or TV while playing.

4.2.4 Appetitive traits

As shown in Table 3, there were also no study group effects on mothers' perception of infant always being hungry at 2 (aOR 0.76, 95% CI 0.37–1.56) and 6 months (aOR 0.46, 95% CI 0.13–1.69).

4.2.5 Total scores of obesogenic risk behaviours

As shown in Table 4, the mean total obesogenic risk behaviour score was 5.29 (SD = 2.01) and 4.03 (SD = 2.00) at 2 and 6 months, respectively. Mothers in the RP intervention had significantly lower obesogenic risk behaviour scores compared to standard care at 2 months (p = 0.009, Cohen's d = −0.37); however, this difference was no longer significant at 6 months (p = 0.06, Cohen's d = −0.32).

| Total score | Mean (SD) | Range | RP intervention mean (SD) | Standard care mean (SD) | p-Value | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 months | 5.29 (2.01) | 1–11 | 4.84 (1.88) | 5.58 (2.04) | 0.009 | −0.37 |

| 6 months | 4.03 (2.00) | 0–9 | 3.59 (1.98) | 4.22 (1.99) | 0.06 | −0.32 |

- Note: Significant results are bolded for emphasis. Abbreviation: RP, responsive parenting; SD, standard deviation.

4.3 Moderating effect of milk type and parity on the effect of study group on obesogenic risk behaviours

Higher order two-way interactions revealed that milk type (any breastmilk vs. exclusive infant formula) and parity did not moderate the effect of study group on any obesogenic risk behaviour or the total obesogenic risk factor scores (data not shown).

5 DISCUSSION

This analysis examined the effect of the WEE Baby Care RP intervention on obesogenic risk behaviours at infant ages 2 and 6 months. Mothers in the RP intervention were less likely to report nighttime feedings at both time points; pressure to finish the bottle at 2 months; screen use when feeding/playing at 2 months; and putting their infant to bed after 8:00 PM at 6 months compared to mothers in standard care. There was no difference in mothers' perception that their infant was always hungry, possibly due to genetic influences and these traits being less amenable to change.33 Reports of infants not eating enough, spitting out food or being picky eaters were rare, as these behaviours may emerge at a later age.34 Mothers in the RP intervention had significantly lower total obesogenic risk behaviour scores than those in standard care at 2 months with a moderate effect size, but there were no significant differences in the obesogenic risk scores at 6 months. These findings suggest that the WEE Baby Care RP intervention positively influenced parenting behaviours related to obesity risk in early infancy among WIC mother–infant dyads. Integrating RP messaging through coordinated care between paediatric clinicians and WIC nutritionists, tailored to meet the needs of each unique family, may help reduce infant obesogenic risk behaviours and promote positive child health outcomes.

Our main findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the WEE Baby Care RP intervention in reducing obesogenic risk during infancy. By targeting multiple obesogenic risk behaviours rather than a single behaviour, this study takes a novel approach to understanding how early interventions can shape healthier infant feeding, eating, sleep and play/activity patterns. The significant reduction in total obesogenic risk behaviour scores among RP intervention participants suggests that addressing a combination of behaviours such as nighttime feedings, pressure to finish bottles, screen use and sleep timing can lead to meaningful improvements in infant health trajectories. Notably, the effectiveness of WEE Baby Care in reducing obesogenic risk behaviours did not differ by milk type (any breastmilk vs. exclusive infant formula) or parity (firstborn vs. not). This finding suggests that our intervention can benefit a wide range of families regardless of infant feeding practices or birth order. Using a total obesogenic risk behaviour score provides a more comprehensive and practical approach to assessing early obesity risk than evaluating individual behaviours in isolation. Findings suggest that the total obesogenic risk behaviour score could serve as an early screening tool. Paediatric clinicians and WIC nutritionists may use the score to identify families needing additional support and allow for tailored guidance to promote long-term healthy eating and growth patterns.

To better understand the effect of the WEE Baby Care RP intervention, we also tested the impact of our intervention on 12 key obesogenic risk behaviours. First, we observed that mothers randomized to the RP coordinated care intervention were less likely to report nighttime feeding. Previous research has shown that reducing the probability of nighttime feeding during night wakings lowered infant BMI.35 Instead of feeding infants back to sleep, WEE Baby mothers were encouraged to use low-stimulus soothing strategies (e.g., rubbing their back and waiting to see if infants fall asleep alone) when their baby did not show signs of hunger.24 Using low-stimulus soothing strategies may help infants learn to self-soothe without feeding,10, 36 which may help prevent overfeeding and promote healthy infant growth.35 It is important to note that even though mothers in the RP intervention used fewer nighttime feeding strategies compared to mothers in standard care, more than half of the mothers in both groups reported nighttime feeding. These data contradict the expectation that infants typically can sleep for longer durations without feeding after 2 months of age.37 More strategies to reduce nighttime feeding may be considered for this population. For example, Brown et al. found infants who consumed fewer calories in the day were more likely to have nighttime feedings, and those who received more milk or solid feedings during the day were less likely to receive nighttime feedings.38

Second, we found that mothers in the RP intervention were less likely to use screens during feeding or playing at 2 months, consistent with a previous study that demonstrated infants in the RP intervention group were more likely to meet the AAP guidelines for daily screen time duration.11 However, it is notable that no such effects were observed at 6 months, suggesting a potential decline in adherence to guidance. Similarly, previous research has shown an increase in screen time as the infant ages.39 Establishing long-term goals to meet AAP recommendations40 may increase parent motivation to reduce screen time during parent-infant interactions. Additionally, two other screen or television exposure-related behaviours—using cellphone or TV while playing and having the TV on in the room when the infant sleeps—were not significantly different between RP intervention and standard care. Screen time and television exposure have been associated with risks such as being overweight,41 poor sleep42 and reduced parent–child interactions.43 Given these risks, it is important to consider enhanced intervention strategies, specifically focusing on reducing screen-based activities during parent-infant interactions.

Our third key finding showed that mothers in the RP intervention were less likely to put their infant to bed after 8:00 PM at age 6 months. Although sleep duration was not collected in this study, previous research suggests that earlier bedtimes are associated with longer sleep duration at night.44 In addition, the AAP recommends that parents put infants to bed drowsy but awake instead of waiting until infants are asleep,24 and our study observed that more mothers in the RP intervention followed this guidance at 2 months of age. This finding is particularly notable as prior research has highlighted the positive effects of RP messaging on earlier bedtimes, longer sleep duration, self-soothing and fewer night wakings in a predominantly white, middle-income sample.10 In contrast, our study extends these findings by including mother–infant dyads enrolled in WIC, a low-income context, which presents unique challenges in establishing healthy sleep habits. Family living in low-income context may experience noise,45 bed- or room-sharing46 and unpredictable work schedules,47 which could be barriers to setting goals and intentions for establishing and maintaining bedtime routines. These challenges should be considered in future interventions targeting families with lower incomes.

Engaging the parent in self-assessment via the EHL risk assessment tool provides clinicians with comprehensive data that complements BMI screening and informs personalized preventive counselling. The validation of this EHL risk assessment tool is currently underway, which would contribute to its implementation and dissemination to achieve broader public health impact. Beyond RP, this analysis enhanced our understanding of integration between clinical and WIC settings to coordinate care and contributes to the advancement of strategies to integrate health and social care delivery.19 In this analysis, mothers' responses recorded in the EHL risk assessment tool, clinical notes and clinician counselling in the RP intervention were shared with WIC nutritionists to boost preventive counselling in the social care setting,23 which benefited BMI outcomes,21 as previously reported. Other studies have demonstrated associations between parent assessments of behavioural and environmental factors in clinical care and healthier BMI outcomes among children.48, 49 Further efforts are necessary to promote equitable access to the EHL risk assessment tool and clinician utilization,50 as well as coordinate health and social care delivery19 to optimize healthy child growth and development.

6 CONCLUSION

A patient-centred, care-coordinated RP intervention decreased the use of obesogenic risk behaviours in feeding and sleep among WIC-enrolled mother–infant dyads. Findings from this study suggest that behaviour-based assessment tools allow parents to evaluate obesogenic risk behaviours and practices with paediatric clinicians and WIC nutritionists to intervene upon them. Findings indicate that personalized screenings for obesogenic risk behaviours impacted the total obesogenic risk behaviour score among a high-risk population. Promoting coordinated care between health care and social care settings may facilitate patient-centred, evidence-based and consistent RP messaging delivery, thereby enhancing efforts to reduce childhood obesity in low-income populations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: YM, AMM, CFR, JSS; Formal analysis: YM, AMM, JSS; Writing—original draft preparation: YM; Writing—intellectual content, review and editing: LB-D, AMM, CFR, CFM, JSS; Supervision: AMM, JSS; Funding acquisition: LB-D, JSS. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their invaluable contributions to this study. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sakshi Bhargava, who served as a research data analyst, for her assistance in data cleaning for this study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Maternal and Child Health Field-initiated Innovative Research Studies Program. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number TL1TR002016. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to the article to disclose.