Direct oral anticoagulants in skin surgery: a systematic review of their complications and recommendations for perioperative management

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding source: None.

Abstract

Introduction

Many patients undergoing cutaneous surgery are prescribed at least one anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent. With the recent emergence of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), there is a deficit of knowledge regarding optimal perioperative management. This review aims to evaluate the evidence and risk surrounding management of DOACs in patients undergoing skin surgeries.

Methods

Systematic review of EMBASE, Scopus, and PubMed, with inclusion of studies that detailed perioperative management of DOACs in those undergoing skin surgery. Primary outcome measures were perioperative hemorrhagic and thromboembolic complications.

Results

Seven thousand seven hundred and forty-one abstracts were identified, with 13 articles meeting inclusion criteria. Two studies investigated complication risk associated with DOAC continuation in skin surgery and found an average rate of hemorrhagic complications of 1.74%. Two studies evaluated complications associated with DOAC cessation prior to skin surgery, with a pooled thromboembolic complication rate of 0.15%. Articles comparing continuation and cessation discovered no decreased risk of bleeding with DOAC cessation prior to surgery (P = 0.93). Seven of the 13 articles compared complications in a control vs a DOAC group undergoing cutaneous procedures. Evidence was conflicting but may have suggested a small increase in bleeding risk in those on DOAC therapy.

Conclusion

Optimal management of anticoagulants perioperatively is difficult because of conflicting information, complicated by advent of novel agents. Risk of hemorrhagic complications with both continuation and interruption of DOAC therapy was low. Perioperative DOAC management can be guided by procedural bleeding and patient clotting risk and can often be continued in minor dermatologic procedures.

Introduction

Many patients undergoing skin surgery are prescribed at least one anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent.1 Skin cancer is rising around the world, with over 2 million new diagnoses of skin cancer each year and a death attributed to melanoma every 4 minutes.2, 3 As a consequence, skin surgery is becoming increasingly more common. For best patient outcomes and in order to minimize patient harms, it is imperative that the skin surgeon is aware of patient factors that may influence the safety of the procedure and perioperative course.

Complicating the landscape is the advent of newer anticoagulant agents, principally the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist (VKA), has been the mainstay of oral anticoagulation over the last five decades.4 However, since the pivotal studies that demonstrated the safety, non-inferiority, and increased convenience of DOAC agents, DOACs have been increasingly prescribed at the expense of VKAs.5

The benefit of cessation or continuation of these during skin surgery is conflicting. There is limited evidence resulting in variations between surgeons regarding patient instructions perioperatively. A recent survey of dermatologists in the United Kingdom demonstrated that 78% of them advised patients to continue their DOAC as usual, with differences depending on the procedure (Mohs micrographic surgery [MMS] vs simple excision) and the optimal timeframe in which to recommence the DOAC if it was paused.6 Of note, 82% of respondents were unaware of a recent update in guidance by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which stipulated that procedures that have “no clinically important bleeding risk”, such as skin excisions, can be performed either just prior to the next dose (with no interruption to DOAC therapy) or by omitting only a single dose.7

Many guidelines and reviews heavily support individualizing one's anticoagulation in the perioperative period on a case-by-case basis or simply recommend their continuation throughout the skin surgery period.8-10 This may be due to the definition of skin surgery varying between simple skin biopsies, to flaps and grafts, to MMS.

Commonly reported limitations of reviews in the field are a paucity of studies that seek to comprehensively describe the effects of DOAC therapy in skin surgeries.11-13 The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the literature on hemorrhagic and thromboembolic complications associated with all perioperative DOAC management in those undergoing skin surgery.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The systematic review follows the reporting guidelines set out by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022311861). A systematic review of the literature was carried out on June 1, 2022, using the databases EMBASE (Ovid), PubMed (Ovid), and Scopus to search for eligible studies. A standardized search approach utilized the Boolean search terms “AND” or “OR”. The search included a combination of terms: Antithromb*, Anticoag*, Direct Oral Anticoag*, Novel Oral Anticoag* AND Dermatosurgery, Cutaneous surgery, Skin surgery: with synonyms, related terms, and subject headings also utilized (see Appendix S1). Given that DOACs entered the prescribing market in 2010 after FDA and TGA approval, the search strategy was limited to January 1, 2010, onwards. No language or species filter was employed in the initial title/abstract search strategy. Reference lists of the eligible articles were also screened to further identify eligible studies.

Inclusion criteria

Levels of evidence to be included in the review include retrospective and prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Included in the review were patients currently prescribed a DOAC, for any reason, and undergoing a cutaneous or dermatological skin procedure. Procedures included in the review were skin excisions and incisions, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), curettage and electrodessication, skin grafts, and skin flaps.

Exclusion criteria

Levels of evidence that were excluded in the review were case reports, case series, and other review articles. Studies without English translation available were excluded from the review. Pediatric (<18 years of age) patients were excluded from the review, as well as any adult patient taking an anticoagulant or antithrombotic therapy that was not a DOAC (e.g., warfarin, heparin, aspirin, clopidogrel, etc.). Those who were taking a DOAC in conjunction with another agent were included if the study authors provided a control subgroup analysis in their work (aspirin vs aspirin and DOAC) or were included as a subgroup analysis in the review separate to DOACs. Procedures were excluded if deemed beyond the scope of the skin surgeon (e.g., reconstructive procedures, large body contouring and liposuction, and procedures relating to other specialties such as oculoplastic procedures performed by ophthalmologists).

Bias

Search results were independently screened by two reviewers (PI & LB) with screening of title and abstracts, with disagreement between eligibility for inclusion settled by a third author (SS). Two authors (PI & LB) assessed the risk of bias in all studies that met eligibility for inclusion and were subject to full-text availability. For prospective and retrospective observational studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Assessment Scale was implemented to assess the risk of bias.14 The Risk of Bias Version 2 (RoB-2) tool was used to assess the risk of bias in eligible RCTs. Data extraction was performed by two authors (PI & LB) working independently utilizing a standardized template.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures were perioperative hemorrhagic complications such as hemorrhage or hematoma, as well as perioperative thromboembolic complications, including but not limited to deep vein thromboses (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), myocardial infarction (MI), and cerebrovascular episodes (stroke, transient ischemic attack, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis).

Results

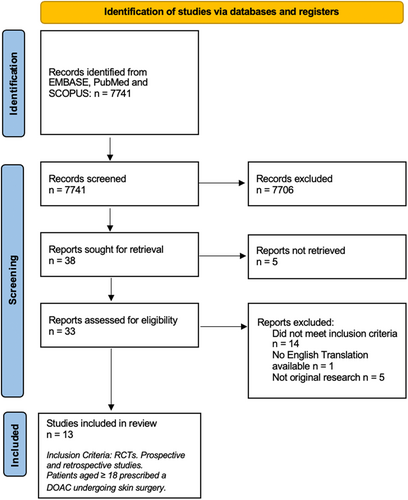

Across the three databases, 7,741 abstracts were identified. Individual screening of the titles and abstracts by authors PI & LB revealed 35 articles for further full-text analysis. Further screening of the full texts of these articles by PI identified 13 articles that met inclusion criteria and were subsequently eligible for analysis and synthesis (Figure 1). Of the 13 articles, four were prospective observational cohort studies, one was a retrospective case–control study, and the remaining eight were retrospective observational cohort studies (Appendix S1).15-27

Over 12 years, there were 10,750 patients who underwent cutaneous surgery, with 1,312 of them performed on patients prescribed a DOAC. The mean participant age ranged from 68 to 78.8 years of age, with a male predominance (49.9–81.8%). The most common indication for anticoagulation with a DOAC was atrial fibrillation. The most common disease being treated was basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and, if location was stated, most commonly involved the head, face, and/or scalp. MMS was the most common cutaneous procedure featured in the relevant articles (7/13 studies), followed by direct excision with a variety of methods of closure (direct closure, healing by secondary wound intention, flaps, and grafts). Complexity and duration of procedures were not described in any included articles.

Given that all the literature eligible for inclusion were observational cohort studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Assessment tool was used to appraise the risk of bias. The majority of studies had a low-medium risk of bias, with two having a high risk of bias.18, 20 Meta-analysis was not feasible due to the significant heterogeneity in methodologies and outcomes.

The included articles studied four areas: (1) complication rate in those who continued DOAC therapy,15, 16 (2) complication rate in those who ceased DOAC therapy prior to undergoing skin surgery,17, 18 (3) complication rate between patients who had their DOAC therapy ceased vs continued,19 and (4) comparing complication rate in patients anticoagulated with a DOAC agent vs a control group not on a DOAC agent (Table 1).20-27

| Author/year | Study design | Relevant medication | Procedures/patients | Body site | Procedure | Outcome | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al. 202120 | Retrospective cohort | Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran |

Total n = 2,386 patients, 2,732 procedures 114 on DOAC therapy 1345 control not on any anticoagulation |

Not stated | MMS |

28 hemorrhagic complication (1.0%) 1 in patient on DOAC (0.9%) 50% of bleeding in patients taking alternative antithrombotic therapy |

Similar risk of bleeding in those on DOAC therapy vs not anticoagulated |

| Langan et al. 202121 | Prospective cohort | Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran |

Total n = 120 8 patients on DOAC therapy 62 not on any anticoagulation |

Not stated | “Skin cancer surgery” | No DVT in 120 patients | Further research is required |

| Jorgensen et al. 202022 | Prospective cohort | Rivaroxaban and apixaban |

Total n = 187 patients on DOAC therapy 76 patients not on any anticoagulation |

Scalp (39), face (106), upper extremities (12), neck and trunk (4), lower extremities (26) | Full thickness or split skin grafting |

17/76 patients not on anticoagulation experienced hemorrhagic complication 1/3 patients who continued DOAC experienced hemorrhagic complication 0/2 patients who interrupted DOAC experienced hemorrhagic complication |

Given limited number, unable to draw conclusions or make recommendations |

| Artamonova et al. 201923 | Retrospective cohort | DOAC and DOAC + Aspirin |

Total n = 528 19 patients were on a NOAC, 3 patients were on a combination of aspirin + DOAC 364 procedures not on any anticoagulation |

Head & face (48.7%), trunk (15.7%), upper extremity (15.4%) | Excision with direct closure, graft, flap, dermal regeneration template or secondary intention |

7/346 (1.92%) not on anticoagulation experienced hemorrhagic complications 0/22 (0%) of those on DOACs experienced hemorrhagic complications |

No statistically significant increased risk of bleeding on DOACs Given low numbers, statistical tests may be underpowered |

| Eilers et al. 201824 | Retrospective case–control | DOAC and DOAC + Aspirin |

Total n = 1,800 procedures 52 patients were on a DOAC, while 12 patients were on a DOAC + aspirin 1226 patients on aspirin (control) |

Zone 1 (833), zone 2 (715), zone 3 (252) | MMS |

26 hemorrhagic complications 4 in patients on DOAC (DOAC or DOAC + aspirin) DOAC vs aspirin had odds risk of 6.7 (P = 0.004) for hemorrhagic complication DOAC and aspirin vs. aspirin had odds risk of 10 for hemorrhagic complication (P = 0.034) |

DOAC or DOAC + Aspirin were significantly associated with hemorrhagic complications |

| Arguello-Guerra et al. 201925 | Retrospective cohort | Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran |

Total n = 655 patients 6 patients on DOAC therapy |

Face, ears, scalp, and limb | Excision with direct closure, flap, graft, or secondary intention healing |

1/443 (0.02%) not on any anticoagulation experienced hemorrhagic complication 0/6 (0%) of those on DOAC experienced hemorrhagic complication |

Antithrombotic therapy may be continued in those with comorbidities undergoing dermatological surgery |

| Heard et al. 201726 | Retrospective cohort | Rivaroxaban |

Total n = 918 procedures 15 patients on rivaroxaban undergoing 18 procedures |

Range of sites | MMS | 3/918 procedures complicated by hemorrhagic complication, all in DOAC group (3/18–17%). 2/3 of these occurred in setting of large random flaps | Continuation of antithrombotic (including rivaroxaban) therapy in those undergoing MMS. |

| O'Neill et al. 201427 | Prospective cohort | Dabigatran |

Total n = 2,418 2 patients on dabigatran 1184 patients not on anticoagulation |

Head & neck, face, trunk, extremities & not reported | MMS |

3/1,184 (0.25%) not on any anticoagulation developed hemorrhagic complication 0/2 (0%) on DOAC experienced hemorrhagic complication |

Cessation of antithrombotic therapy does not appear warranted, however unable to advise given small sample size |

Outcomes

DOAC continuation

Antia et al.15 evaluated 76 MMS on patients who were prescribed a DOAC, resulting in one mild bleeding complication in a person taking rivaroxaban (1.32%). Chang et al. conducted 46 procedures in patients on DOAC therapy (41 on dabigatran and five on rivaroxaban).16 There was one mild bleeding complication in the dabigatran group (2.44% of the dabigatran group, 2.17% of all DOAC), and no complications in the rivaroxaban group. Pooled mean from Antia et al. and Chang et al. gives a hemorrhagic complication rate of 1.71% in patients anticoagulated with DOACs undergoing skin procedures.

DOAC cessation

In Siscos et al.,17 750 patients underwent 806 MMS, all adhering to a DOAC interruption protocol involving cessation of their DOAC 1 day before surgery and resuming 1 day after. One patient sustained a TIA (0.12%), while two patients sustained minor bleeding complications (0.25%). Schulman et al.18 used a specific protocol based on creatinine clearance and invasiveness of the procedure in order to cease dabigatran and investigate the safety of this cessation. Five hundred and forty-one procedures were performed, of which 16 were skin procedures. Thirteen of 16 skin procedures were classified as ‘standard risk’, while 3/16 procedures were classified as ‘high risk’ (defined as a procedure in which complete hemostasis is required). Only pooled outcomes were published with no dermatologic procedure subgroup. Of the 541 total patients, 10 patients had major bleeding (1.85%), 28 patients had minor bleeding (5.18%), and a TIA occurred in one patient (0.18%).

DOAC cessation vs. continuation

Sheikh et al.19 evaluated 1412 procedures, of which 129 procedures were skin procedures on patients taking a DOAC. One hundred twelve patients (86.8%) continued their DOAC therapy, while 17 patients (13.2%) had their DOAC regime interrupted. There were 11 (9.82%) bleeding complications in the continuation group and three (17.65%) in the patients who had their DOAC interrupted. Overall, there was a reported slightly decreased risk of any bleeding events with DOAC interruption (P = 0.03) for pooled procedures; however, individual analysis found no decreased risk of bleeding (P = 0.93) for the dermatologic procedures' subgroup. There were no differences in thromboembolic events or deaths between the two groups.

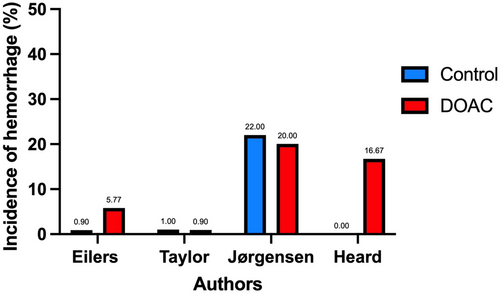

DOAC vs. control

Eight of the 13 articles evaluated the rate of hemorrhagic complications in patients undergoing skin surgery (Table 1), comparing those on a DOAC with a control group (Figure 2).20-27 Studies with non-events were excluded from graphical comparison.

Discussion

This systematic review analyzed 13 articles evaluating 10,750 patients who underwent cutaneous surgery. Of these, there were 1,312 procedures performed on patients who were prescribed a DOAC. As a whole, the evidence surrounding the perioperative management of DOACs in patients who undergo skin surgery offered no single unifying recommendation.15-27 Many authors deemed the continuation of DOAC therapy throughout the procedure to be safe or that there was no increased risk of hemorrhagic complications.15, 16, 23, 25 In contrast, various authors found that interrupting DOAC therapy conferred little thromboembolic risk while minimizing hemorrhagic complications.17-19 Two studies concluded that DOAC therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding when compared to a control group.24, 26 Many of the authors go on to describe that given the small sample size of patients on DOAC therapy or those who experienced complications, limited conclusions could be derived from the studies and that further research is required for more definitive recommendations.16-18, 25

The optimal management of a patient's anticoagulation is a difficult balance for the clinician to perfect; on one hand, arterial or venous thromboembolic complications are a very real and devastating concern. Conversely, continuing one's anticoagulation unnecessarily perioperatively can predispose to serious sequelae, including hemorrhage, poor wound healing, and infection.28 In the skin surgery setting, this can lead to poor cosmetic outcomes, dehiscence, and tissue necrosis requiring extended antimicrobial regimes and take-back procedures.28, 29

There exists a paucity in the literature of RCTs that evaluate the periprocedural management of DOACs in skin surgery, and hence there were none eligible for inclusion. Several studies have addressed the issue from a broader perspective, providing recommendations for use in varying clinical contexts based on findings derived from other fields of medicine.30, 31 Unfortunately, they often provide little stratification for the bleeding risk of dermatologic specific procedures.

Skin procedures are diverse and heterogeneous in nature, ranging from small biopsies and simple excisions to reconstructive plastic surgeries requiring large flaps and full-thickness grafts which may pose a higher risk of bleeding. Despite this, the vast majority of cutaneous procedures are defined as those posing a minimal or low bleeding risk, described as a 0–2% chance of incurring major bleeding, commonly defined as bleeding into a critical anatomic site, lowering hemoglobin by ≥20 g/l or requiring ≥2 units of packed blood cell transfusions.32

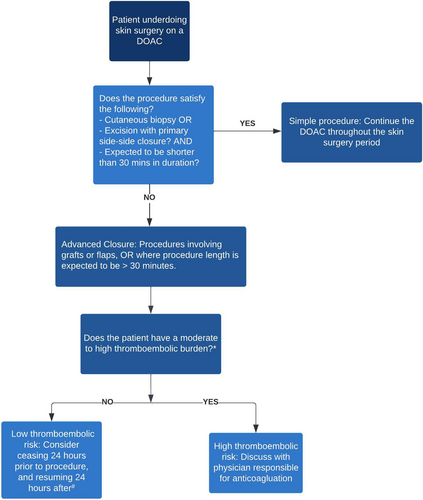

In light of the literature, we recommend an approach that considers these issues in the perioperative period: (1) What is the inherent bleeding risk associated with the procedure? and (2) What is the thromboembolic risk in this patient?

For procedural bleeding risk in skin surgery, the authors recommend the following approach detailing two levels of bleeding risk. The first level includes minor dermatologic procedures such as cutaneous biopsies (excluding full-thickness excision), excision with primary side-to-side closure, and procedures with expected duration <30 minutes. The second level includes procedures where advanced closure is required, including grafts and flaps, or where duration is >30 minutes.

Secondly, determining the thromboembolic propensity of the patient is vital in underpinning optimal perioperative anticoagulation management. Patients can be defined as low, moderate, or high risk of thromboembolism (Table 2).31

| Low | Moderate | High | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation |

|

|

|

| Venous thromboembolism (VTE) |

|

|

|

- CHADS2, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke or TIA previously.

Based on bleeding and thromboembolic risk, the authors propose recommendations based on these two levels and subsequent perioperative management of DOACs (Figure 3).

Please note that following this decision tree is to be used as a guide only and should not supersede clinical gestalt. If the decision to withhold anticoagulants is made, counseling the patient on the increased risk of thromboembolic disease must be carried out. In addition, the review undertaken and the recommendations made are only applicable to low-risk dermatologic procedures involving DOACs. This decision process should not be applied to any other type or procedure or any other antithrombotic agent due to differences in pharmacokinetics and bleeding risk. The decision to continue or interrupt one's DOAC regime based on clinical decision tools needs to be validated and ideally further studied in RCTs.

It was the view of the authors to include all types of skin procedures (ranging from minor biopsies to full-thickness skin grafts) that have served as delineation points in other reviews, so as to capture all relevant evidence. Subspecialist procedures relating to the skin that were not covered by skin surgeons, such as reconstructive oculoplastic procedures performed by ophthalmologists, were deemed less relevant to the skin surgeon and were thus excluded from the review. Of note, however, it was recently reported that there are “no studies investigating the safety of continuing DOACs perioperatively in patients undergoing oculoplastic and lacrimal surgery”.33

Many studies included did not have a sufficient sample size of patients receiving DOAC therapy to amount to statistical power,16-18, 20, 25 and either did not have a comparator control cohort15-18 or had a control cohort without clinician blinding.21, 22, 27 Often, there was very little definition provided for hemorrhagic complication and the level of intervention required to achieve hemostasis, while only one study attempted to stratify patients based on the dose of their DOAC (low-dose vs high-dose apixaban and rivaroxaban).19 Only one study attempted to account for confounders associated with hemorrhagic or thromboembolic complications (e.g., smoking, comorbidities, procedure, and closure type).19 Studies could serve to benefit from detailing complexity of procedure and procedure length, as while patients who were on DOACs may not have experienced postoperative hemorrhagic complications, procedural length may have increased in order to achieve intraoperative hemostasis.34 Direct comparison of outcomes was difficult across studies given the heterogeneity in reporting outcomes and measured parameters.

In studies nonspecific to dermatological or cutaneous surgeries, often no subgroup analysis of cutaneous procedures was performed or reported, meaning that any complications and conclusions made were extrapolated based on findings of procedures deemed to be of a similar risk profile.19 The methodology implemented for the identification and reporting of complications in the postoperative period was extremely heterogeneous and subject to bias and imprecision. While some studies had a follow-up organized at a specified time with the reporting clinician, one study relied on patients to re-present within 3 weeks if they noticed a complication.21 The majority of the procedures were MMS and skin cancer excisions performed on either the head, face or scalp, meaning that any conclusions drawn should only be applied to similar clinical contexts.

Indeed, in the absence of high-quality evidence or consistent international guidelines providing a consensus on ideal management of DOAC therapy in cutaneous surgery, several surveys of dermatologist practice undertaken globally reflect a trend toward individualized approaches. Chiang et al. surveyed 67 dermatologists across the UK with respondents generally recommending to their patients the continuation of DOAC therapy pre- and postoperatively in low bleeding-risk procedures such as minor skin excisions.6 Logically, as the size of the excision or complexity of the surgical procedure increased, the proportion of dermatologists recommending uninterrupted DOAC therapy decreased. Similarly, a more recent survey of over 250 German dermatological surgeons found the vast majority (>70%) continued rivaroxaban in the setting of small (e.g., nevus) and large (e.g., melanoma) skin excisions with practices remaining consistent between hospital and office-based clinicians.35 For larger excisions and sentinel lymph node biopsies (procedures only performed by the hospital-based dermatologists surveyed), the proportions of those continuing DOAC therapy was reduced to between 15 and 30%. Han et al. found dermatological surgeons were more likely to continue DOAC therapy when compared with plastic and reconstructive surgeons in a survey of US-based clinicians performing cutaneous surgery, likely reflecting the increased complexity and invasivness of cutaneous surgery performed by plastic surgeons.36

While there is no unifying recommendation, guidelines lean in favor of continuing DOACs in skin surgery in the majority of instances. Given this, one has to ask the question as to why many clinicians continue to withhold DOACs in skin procedures. As previously described, DOACs have been in one's armamentarium for as little as 10 years, suggesting that the prejudice of dermatologists to discontinue these agents may be based on their familiarity with medications such as warfarin and aspirin. Some studies document that the risk of hemorrhagic complications in patients taking warfarin can be up to three-fold higher than their non-anticoagulated counterparts, warranting consideration for interruption perioperatively.37 Efforts need to be made to reassure dermatologic surgeons that minor skin procedures can be performed in patients without changes to their DOAC regime, especially in those with higher thromboembolic burden.

Conclusion

The evidence characterizing the literature of anticoagulants in skin surgery is conflicting, often differing based on the antithrombotic agent and the nature of the procedure. This systematic review largely found that either the continuation or cessation of DOAC therapy in the perioperative period was safe, with minimal complications of hemorrhage or thromboembolism, often comparable to the general population.

The authors present a set of recommendations based on two levels of skin surgery, defined as simple or those requiring advanced closure. Those performing skin surgery should feel reassured that continuing a patient's DOAC will be safe and practical in the majority of procedures. Future studies validating this approach would serve to benefit the sphere of literature on perioperative DOAC management.

Acknowledgment

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Author contributions

All authors satisfied the ICMJE criteria for authorship. Patrick Ireland – conceptualization, selection criteria, data screening, data collection and synthesis, manuscript drafting, manuscript editing. Luca Borruso – conceptualization, data screening, data collection and synthesis, manuscript drafting. Sascha Spencer – conceptualization, manuscript editing. Richard Rosen – conceptualization, manuscript editing. Robert Rosen – conceptualization, selection criteria, manuscript editing, supervision. All authors were involved in the organization, coordination, conduction, critical review of the manuscript, and approval of the final version.

Open Research

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.