The link between trait and state professional skepticism: A review of the literature and a meta-regression analysis

Funding information: Charles Sturt University, Grant/Award Number: Early Career Research funding

Abstract

Motivated by the need to better understand the trait–state skepticism relationship, and also building upon prior literature syntheses, this study examines the literature that empirically investigates the trait–state skepticism relationship using experimental methodology. A meta-regression analysis is conducted on Pearson correlations between trait skepticism and state skepticism to identify the overall effect and key drivers of this relationship. On average, there is no noticeable effect size for the relation between trait and state skepticisim across the studies; however, there are three key determinants of the correlation across studies mainly (1) the use of the Inverse Rotter trait measure compared to other measures reduces the correlation, (2) the use of graduate auditor samples compared to seasoned professionals intensifies the correlation and (3) the use of a low risk environment in the research design reduces correlation. The review and analysis are timely as the literature re-examines how professional skepticism is conceptualized and operationalized moving forward.

1 INTRODUCTION

Professional skepticism continues to be an issue of interest and debate in audit research, where issues with audit quality are attributed, in part, to a lack of professional skepticism (Hurtt, 2010; Nelson, 2009; Nolder & Kadous, 2018). The criticism appears to be directed towards auditors for not sufficiently exercising appropriate levels of professional skepticism in their duties. For example, insufficient exercise of professional skepticism may manifest in an auditor's inability to respond adequately to the risk of material misstatement (audit judgment) or even in difficulties faced when assessing the risk of material misstatement (audit action). In response to these criticisms of the audit profession, there is continued research in the audit literature on professional skepticism where the main challenge faced by this stream of research is reliably capturing the conceptual variable of professional skepticism.

Professional skepticism is clearly prescribed in the auditing standards, since the International Standards on Auditing requires that ‘the auditor shall plan and perform an audit with professional skepticism recognizing that circumstances may exist that cause the financial statements to be materially misstated’ (International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, or IAASB, 2018). A major challenge faced by audit research in investigating conditions under which auditors exercise professional skepticism is the inherent difficulty in capturing skepticism both as a trait and state construct. If professional skepticism is accurately captured as a construct, then there should be a strong association between an auditor's innate level of professional skepticism (i.e. trait skepticisim and their beliefs) and skepticism as it is applied as a state in an audit context (i.e. state skepticisim and their actions and judgments). It appears that the existing body of literature has not identified a consistent strong association between trait and state skepticisim (Hammersley, 2011). The nature of this relationship also appears to vary among experimental studies in the literature. The main purpose of this study is to assess whether, across all previous studies on average, a positive relationship exists between trait and state skepticism and whether factors such as study design, sample choice and other factors explain the variation in results across these experimental studies.

Trait skepticism is a persistent personality construct that individuals have at different levels, whereas state skepticism is the observed application of this trait in a given context, such as audit judgments and actions (Hurtt, 2010; Naylor, 1981; Nelson, 2009). Recent research suggests that the literature is moving away from examining innate traits in isolation and instead focusing more on situational determinants within the audit context. This development is important given the unique nature of an increasingly complex audit engagement environment, which can span multiple teams and work settings (Nolder & Kadous, 2018).

The profession has debated whether audit firm hiring policies should consider the skeptical dispositions of aspiring auditors, in terms of evidence of engaging in skeptical actions as opposed to auditors' underlying skeptical beliefs (e.g. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, 2012; Westermann et al., 2019). This debate is relevant as skeptical belief as a construct (measured using a scale) does not appear have a strong consistent association with observed skeptical actions and judgments (i.e. state skepticism) based on research findings to date (Hurtt et al., 2013; Nolder & Kadous, 2018). Despite some evidence that the academic literature is moving away from traits and increasing its focus on situational determinants, in the professional sphere, the role of traits is still considered to be as important as situational determinants (Nelson, 2009; Nolder & Kadous, 2018).

The unclear relationship between trait skepticism and state skepticism is evident in Hurtt et al.'s (2013) literature review, which reveals how the direction of this relationship (positive/negative) varies among studies, and in some studies, no significant associations are identified. Clarity on how professional skepticism is measured and applied in an audit context is important for both research and practice (Stevens et al., 2019). Hence, it is important to also examine how the literature has measured and operationalized professional skepticism as a trait construct, and its association with skeptical actions and/or judgments (i.e. state skepticism).

This paper differs from prior literature reviews (Hurtt et al., 2013; Nelson, 2009) in that it provides a descriptive summary of the main measures used to operationalize skepticism in the accounting and audit literature and, as its key contribution, a meta-regression analysis (MRA) of the correlations of the trait–state skepticism across studies.1 The purpose of conducting the MRA on published correlations is to first estimate the overall average correlation between trait skepticism and state skepticism documented in the literature and second to identify the key determinants of the variation in observed correlations between trait and state skepticism found among studies. After controlling for publication bias, the analysis reveals that there is no statistically significant empirical association between trait and state skepticism. Further, the MRA identifies important and intuitive key drivers of the trait–state relationship, particularly the nature of the sample employed in terms of the level and experience of the auditors, as well as situational factors in the audit environment in terms of the apparent level of risk. The MRA is unique in that it calculates and documents a quantitative empirical result to validate prior interpretations and implications of the trait–state skepticism relationship reported in experimental studies.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: to provide the appropriate context, Section 2 discusses the key concepts and seminal developments in the professional skepticism literature. Section 3 presents the process for the meta-analysis and general descriptive findings for measuring professional skepticism. Section 4 reports the MRA by examining published correlations between trait skepticism and state skepticism. Finally, Section 5 provides concluding remarks regarding the literature synthesis as informed by the findings of the MRA.

2 TRAIT AND STATE SKEPTICISM

In conducting the meta-analysis, it is important to understand the development of the trait–state skepticism framework in the audit literature. The first conceptual model was presented by Nelson (2009) and operationalized by Hurtt (2010), and these papers provide a framework for the experimental examination of professional skepticism. Nolder and Kadous (2018) recently developed and proposed a new framework and model for professional skepticism as a way forward for the literature.

Nelson (2009) reviewed the literature and offered a seminal framework and conceptualization of the trait–state skepticism relationship. The literature review identified traits (among other antecedents) as determinants of skeptical judgment and skeptical action (both proxies for state skepticism). Although the study primarily focused on skepticism as an observable state (as either action or judgment, or both), it also provided an understanding of how an individual's traits and dispositions can be reflected in state skepticism. In light of Nelson's framework, our study distinguishes between audit action and audit judgment when identifying and operationalizing state skepticism (as either skeptical action or skeptical judgment).

Hurtt (2010) developed the 30-item skepticism scale that has since been widely tested and validated. Since the scale's publication, more than 35 studies (including seven working papers) have utilized it to measure and report trait skepticism. This scale measures trait skepticism as a construct with six distinct dimensions: self-confidence, interpersonal understanding, a questioning mind, suspension of judgment, the search for knowledge and self-determination. In developing a measure for trait skepticism, Hurtt (2010) also presented a model based on the findings of Nelson (2009), where state skepticism is viewed as a reflection of trait skepticism, operationalized as judgments and/or actions taken by auditors.

Nolder and Kadous (2018) introduced and proposed a new framework and model for professional skepticism, one that presents a unique duality in the conceptualization of professional skepticism, by presenting skepticism as both a mindset and an attitude influenced by situational factors within the audit context. Guided by this novel understanding of professional skepticism, one which situates traits within the audit work environment and its unique features, the authors also proposed ways in which trait skepticism could be measured in a manner consistent with this proposed dual conceptualization of skepticism, one that is more situated in the audit context.

Nolder and Kadous (2018) strongly reaffirmed the notion of professional skepticism as an ill-defined and mis-measured construct given the mixed findings reported in the literature (Hurtt et al., 2013). In light of these mixed findings in the literature, the application of professional skepticism has not been clear in professional practice, as it remains unclear why auditors have not been able to meet expectations when it comes to professional skepticism (Hammersley, 2011; Nelson, 2009). To better understand the overall average effect and then subsequently identify the key drivers and determinants of the trait–state skepticism relationship, it is important to have a clear understanding of how the literature has measured and operationalized the trait skepticism construct to date.

Prior to Nolder and Kadous (2018), the proposed theoretical framework underlying professional skepticism (Hurtt, 2010) suggested an intuitive positive relationship between trait skepticism and state skepticism. High levels of trait skepticism present in an individual should logically result in high levels of state skepticism being reflected in the individual's judgments and actions (Hurtt, 2010; Nelson, 2009; Nolder & Kadous, 2018). Despite this intuitively designed and validated framework, the findings of experiment-based studies are not always consistent with the intuition that there should be a positive and significant relationship between trait and state skepticism (Hurtt et al., 2013). Specifically, higher levels of measured trait skepticism are not always apparent in higher levels of state skepticism measured in audit judgments and actions (Hammersley, 2011). In some instances, the findings reported in these studies have indicated otherwise (Harding & Trotman, 2017). This could be largely due to differences in experimental design, which could also be why the findings tend to differ when investigating the trait–state skepticism relationship, and despite operationalizing trait skepticism using common, validated scales.

Consistent with theoretical expectations, some experimental studies on professional skepticism in the audit literature reaffirmed a positive relationship between trait skepticism and state skepticism (Eutsler et al., 2018; Farag & Elias, 2012). However, most studies provided statistically weak and sometimes non-significant evidence of a positive trait–state skepticism relationship, and in some instances found the opposite; a negative relationship between trait and state skepticism (Carpenter & Reimers, 2013; Harding & Trotman, 2017). Understanding how trait skepticism has been operationalized in the experimental literature is imperative to better understanding the trait–state skepticism relationship measured in the literature.

The main purpose of our meta-analysis is to summarize what other researchers have characterized as a literature with mixed findings on professional skepticism. The analysis will partly seek to describe the findings to date in terms of the manner in which professional skepticism has been measured and operationalized. This is then followed by the MRA on published trait–state skepticism correlations.

3 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS

3.1 Procedure

Consistent with Hay's (2019) call, we employ best practice techniques to conduct the meta-analysis. The procedures for the literature search and collating, coding and analysing the data follow the guidelines developed by the MAR-Net group (Stanley et al., 2013). Explicit details of the techniques for reporting and summarizing the data and developing the MRA were provided by Stanley and Doucouliagos (2012). We employ these methods and some more recent developments in developing meta-regression models (e.g. Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2014, 2017).

A search of the literature in October 2018 was conducted by a university librarian on subscribed journals and databases available within the university's electronic library resources, covering the databases of Taylor & Francis, ProQuest Business, Wiley Online Library, Scopus, Emerald Insight and Springerlink. The search criteria included material published between 1996 and 2018, and the keywords skepticism/scepticism, professional skepticism/scepticism and audit were used. The researchers also conducted their own literature search, using the same criteria via Google Scholar. The literature synthesis conducted by Hurtt et al. (2013) also served as a useful guide and reference in the search, in addition to the concise summary of studies collated by Robinson et al. (2018) that measured skepticism using the Hurtt (2010) scale.

The first search, in October 2018, focused on articles published only in journals. This was followed by a second search a month later, in November 2018, which focused on working papers and other publications (e.g. peer-reviewed book chapters) found in the Social Science Research Network (SSRN). In shortlisting the articles, care was taken to ensure only experimental studies that measured professional skepticism were included in the meta-analysis. This implies that all editorials, professional commentaries and any publication that was qualitative were excluded. A final replication search was completed by a different university librarian in March 2020. This search followed the same parameters as prior searches and extended it to additional databases, namely, Business Source Complete, ABI, Web of Science and Research Gate.

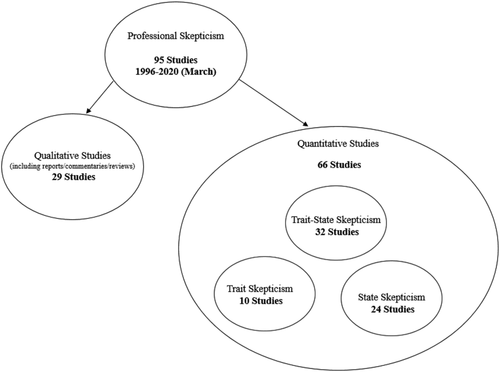

The search, which included working papers, identified 95 studies that differed in terms of the research methods employed. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of how the studies are classified and selected. For the purpose of the meta-regression, we focus on quantitative research, for which 66 studies are identified. Of these studies, 32 measured and tested the empirical relationship between trait skepticism and state skepticism.

The meta-analysis of measures of trait skepticism includes 35 studies, and the MRA uses the Pearson correlations between trait and state skepticism reported in 14 studies. The authors completed the coding on their own. First, the authors each coded a few papers and then compared notes. Following this, one author completed the remainder of the coding, with the other author conducting regular checks. In the initial coding, certain variables were identified from the outset; however, subsequent observations resulted in additional variables being coded, as shown in Table 1.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Panel A: | Initial variables collected |

| Journal rank | A*, A, B, C, unranked (U), or working paper (WP) |

| Publication year | Year of publication (20XX) |

| Study year | Year of study (20XX) |

| Sample size | Number of participants (n) |

| Location | Sample country of origin |

| Experiment mode | Controlled or uncontrolled |

| Language | Language in which the study materials were presented |

| Student/practitioner | Whether the sample comprised students or practitioners |

| Trait skepticism (measure) | The scale used to measure trait skepticism |

| Trait skepticism (mean) | The mean score of the skepticism measure |

| Trait skepticism Cronbach's α | Cronbach's α of the skepticism measure |

| Trait skepticism standard deviation | Standard deviation of the skepticism measure |

| Manipulated variables | List of variables manipulated in the experiment design |

| Other variables | Inclusion of any other variables (controls) in the experiment |

| State skepticism measure | Operationalization of state skepticism |

| State skepticism judgment/action | Whether state skepticism was a judgment or action |

| State skepticism mean | Mean score of the skepticism measure |

| State skepticism standard deviation | Standard deviation of the skepticism measure |

| Pearson correlation | Pearson correlation coefficient between trait and state skepticism |

| t-value | Pearson correlation t-value |

| p-value | Pearson correlation p-value |

| Panel B | Variables collected after preliminary analysis |

| Risk environment | High-, low -, or neutral-risk experiment case environment |

| Risk assessment | Whether the experiment material involved making a risk assessment |

| Direction of trait skepticism | Whether the scale score indicated increasing or decreasing levels of trait skepticism |

| Direction of state skepticism | Whether the score indicated increasing or decreasing levels of state skepticism |

| State skepticism Cronbach's α | Cronbach's α of the skepticism measure |

3.2 Trait skepticism measures

Table 2 lists all the scales that have been used to date to measure trait skepticism. Trait skepticism has predominantly been measured using the Hurtt (2010) scale and the inverse of Rotter's (1967) Interpersonal Trust scale. The Hurtt scale has represented the neutrality perspective of professional skepticism, whereas the inverse of the Rotter scale has represented the presumptive doubt perspective of professional skepticism. These have been the two predominant perspectives on professional skepticism in the audit literature (Cohen et al., 2017; Quadackers et al., 2014). Some studies have also used self-created measures, but their application and generalizability have not been as widespread as the aforementioned measures captured by Hurtt and Rotter.

| Scale | Items | Score range | Mean | Studies | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurtt | 30 | 30–180 | 135.23 | 35 |

High: 0.97 Low: 0.68 |

| Inverse rotter interpersonal trust | 25 | 25–125 | 74.77 | 4 |

High: 0.82 Low: 0.76 |

| Interdependent self-construal | 12 | 12–60 | 45.00 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Independent self-construal | 12 | 12–60 | 42.70 | 1 | 0.70 |

| Locus for control | 23 | 0–23 | 10.06 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Need for closure | 42 | 42–252 | 154.85 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Independent self-created measure | - | - | - | 5 | 0.88 |

Our descriptive summary primarily focuses on the Hurtt (2010) scale to measure professional skepticism as a trait, because this has been the predominant manner in which professional skepticism has been operationalized in the literature. It is also the scale that has guided the discipline in terms of how professional skepticism is measured and operationalized and then subsequently communicated to both researchers and professionals (Cohen et al., 2017). The following section discusses how the Hurtt scale has been employed in professional skepticism research.

3.3 Hurtt trait skepticism measure

As collated in Table 3, the literature search reveals that 35 studies (including seven working papers) have utilized the Hurtt (2010) scale. In the wider sample of studies collected, 12 studies also used alternative measures for professional skepticism (with or without the Hurtt measure), including the inverse of the Rotter (1967) Interpersonal Trust Scale and other self-created measures.

| Paper | Journala | ABCD rank | Publication year | Study year | Sample | Location | Experiment mode | Language | Student/practitioner | Type | Skepticism (measured) | Skepticism (Cronbach) | Skepticism (mean) | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ying et al. (2020) | ABR | A | 2020 | 2019 | 115 | China | Uncontrolled | Chinese | Practitioner | Associate, senior, manager, and partner | Hurtt | 0.892 | 132.46 | ANOVA |

| Ciołek and Emerling (2019) | S | C | 2019 | 2017 | 432 | Poland | Controlled | Polish | Student | Undergraduate, graduate | Hurtt | 0.81 | ANOVA | |

| Ghani et al. (2019) | PJMS | U | 2019 | 2018 | 94 | Malaysia | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Internal | Hurtt | 0.884 | Regression | |

| Rahim et al. (2019) | JA | U | 2019 | 2017 | 40 | Indonesia | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Senior, junior, and partner | Hurtt | 0.97 | SEM and PLS | |

| Yustina and Gonadi (2019) | JAK | U | 2019 | 2018 | 163 | Indonesia | Uncontrolled | English/Indonesian | Practitioner | Associate, junior, senior, manager, and supervisor | Hurtt | 0.918 | 2.969 | SEM and PLS |

| Eutsler et al. (2018) | AJPT | A* | 2018 | 2014 | 49 | United States | Controlled | English | Student | Postgraduate | Hurtt | 0.87 | 135.7 | GEE |

| Favere-Marchesi & Emby, 2018 | AH | A | 2018 | 2015 | 140 | United States and Canada | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Manager | Hurtt | ANOVA | ||

| Fatmawati & Fransiska, 2018 | UKMJM | U | 2018 | 2017 | 227 | Indonesia | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate, professional | Hurtt | 0.831 | 136.44 | ANOVA |

| Knechel et al. (2018) | WP | WP | 2018 | 2014 | 702 | Sweden | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Big 4 lead auditor | Hurtt | 0.887 | 75.86 | Regression |

| 1196 | Sweden | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Non-big 4 lead auditor | Hurtt | 0.887 | 76.61 | Regression | |||||

| Boritz et al. (2018) | WP | WP | 2018 | 2017 | 275 | Canada | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | 125.62 | ANOVA | |

| Robinson et al. (2018) | AJPT | A* | 2018 | 2016 | 126 | United States | Controlled | English | Practitioner | Senior | Hurtt | 0.88 | 131.2 | Factor analysis |

| 64 | United States | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | 0.92 | 139.5 | Factor analysis | |||||

| 54 | United States | Controlled | English | Student | Graduate | Hurtt | 0.86 | 146.1 | Factor analysis | |||||

| Cohen et al. (2017) | AOS | A* | 2017 | 2015 | 176 | United States | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | 10 staff, 100 senior auditors, 66 managers | Hurtt | 0.87 | 4.69 | PLS |

| Winardi & Pernama, 2017 | JRAI | U | 2017 | 2016 | 107 | Indonesia | Controlled | English | Student | 53 undergraduate students, 46 postgraduate students, 8 professional students | Hurtt | 0.866 | ANOVA | |

| Yazid & Suryanto, 2017 | IJEP | C | 2017 | 2016 | 115 | Indonesia | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Staff | Hurtt | 0.963 | SEM | |

| Agarwalla et al., 2017 | AIA | A | 2017 | 2015 | 90 | India | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Manager, CA | Hurtt | 0.71 | ANOVA and regression | |

| Aschauer et al., 2016 | BRIA | A | 2016 | 2014 | 233 | Germany | Uncontrolled | German | Practitioner | Dyads (lead and concurring auditors) | Hurtt | 0.675 | 5.36 | OLS |

| Bhaskar et al., 2016 | WP | WP | 2016 | 2014 | 152 | United States | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate, graduate | Hurtt | 133.5 | OLS | |

| Farag and Elias (2016) | JAE | B | 2016 | 2014 | 293 | United States | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | 136.32 | ANOVA | |

| Koch et al. (2016) | WP | WP | 2016 | 253 | Germany | Controlled | German | Practitioner | 87 senior auditors, 120 managers, 42 partners, 4 unknown | Hurtt | 0.87 | 135.3 | ANOVA and SEM | |

| Kwock et al. (2016) | CJAS | U | 2016 | 2014 | 127 | China | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | Factor analysis | ||

| Ho et al. (2015) | JBS | C | 2015 | 2014 | 127 | China | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | Factor analysis | ||

| Rasso (2015) | AOS | A* | 2015 | 2013 | 58 | United States | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Staff, senior, manager, and partner | Hurtt | 129.71 | ANOVA | |

| Hussin and Iskandar (2015) | EAF | C | 2015 | 2014 | 56 | Malaysia | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | 27 junior auditors, 17 senior auditors, 10 managers, 2 partners | Hurtt | Factor analysis | ||

| Law and Yuen (2015) | AE | A | 2015 | 2014 | 401 | United States | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | 217 big N and 184 non-big N auditors | Hurtt | Regression | ||

| 373 | China | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | 190 big N and 183 non-big N auditors | Hurtt | Regression | |||||||

| Noviyanti and Winata (2015) | CMR | U | 2015 | 2013 | 62 | Australia | Controlled | English | Practitioner | 20 senior auditors, 42 junior auditors | Hurtt | 0.747 | 82.5806 | ANOVA |

| Peytcheva (2014) | MAJ | B | 2014 | 2012 | 78 | United States | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | 0.88 | 74.27 | Regression |

| 85 | United States | Controlled | English | Practitioner | 27 associates, 28 senior auditors, 18 managers, 12 partners | Hurtt | 0.84 | 75.51 | Regression | |||||

| Pike and Smith (2014) | JFSA | C | 2014 | 2013 | 319 | United States | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | CFE | Hurtt | 144.9 | Factor analysis | |

| 294 | United States | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | CPA | Hurtt | 137.3 | Factor analysis | ||||||

| Quadackers et al. (2014) | CAR | A* | 2014 | 2011 | 96 | Netherlands | Controlled | Dutch | Practitioner | 25 partners, 41 managers, 27 senior auditors | Hurtt | 0.834 | 133.09 | Regression |

| Carpenter and Reimers (2013) | BRIA | A | 2013 | 2011 | 80 | United States | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | Big 4 managers | Hurtt | 140.99 | ANOVA | |

| Urboniene et al. (2013) | IJGBMR | U | 2013 | 2012 | 109 | Lithuania | Controlled | Lithuanian | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | 110.5 | ANOVA | |

| Castro (2013) | WP | WP | 2013 | 2012 | 199 | Canada and United States | Uncontrolled | English | Practitioner | 40 staff, 20 supervisors, 45 managers, 39 directors, 55 executives | Hurtt | 0.897 | ANOVA | |

| Farag and Elias (2012) | PREA | B | 2012 | 2011 | 278 | United States | Uncontrolled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | 134.9 | ANOVA | |

| Popova (2012) | MAJ | B | 2012 | 2009 | 79 | United States | Controlled | English | Student | Undergraduate | Hurtt | 131.5 | ANOVA | |

| Quadackers et al. (2009) | WP | WP | 2009 | 2006 | 181 | Netherlands | Controlled | Dutch | Practitioner | 26 partners, 91 managers, 59 senior auditors, 2 staff | Hurtt | 0.821 | 131.66 | Regression |

| Hurtt et al. (2008) | WP | WP | 2008 | 2007 | 83 | United States | Controlled | English | Practitioner | Hurtt | 138.7 | ANOVA |

- aU, unranked publication; WP, working paper.

The 30-item Hurtt scale elicits responses on a 6-point agree/disagree scale, with each item added up (after reverse-coding eight items) to calculate a score from 30 to 180. The mean skepticism score across all studies (based on 28 reported means) is 135.2.2 This figure is consistent with the means reported by Hurtt (2010) during the development and validation of the scale itself, where the mean skepticism scores for the student and professional samples were 132.7 and 138.6, respectively (Hurtt, 2010, p. 161). On average, the self-reported means are sufficiently high across both student and practitioner samples, and the scale has proven to be reliable, as shown in Table 2, where the highest reported Cronbach α is 0.97, which indicates greater reliability than the other competing measures used in the skepticism literature. It should also be noted that the lowest reported Cronbach α for the Hurtt skepticism measure is 0.68, with an average of approximately 0.85. Overall, since its publication in 2010, the Hurtt measure for trait skepticism has proven to be consistently reliable in measuring trait skepticism, as well as reliably distinctive between individuals with higher/lower levels of trait skepticism. The sample, on average, reports the levels of trait skepticism consistent with expectations in the profession when compared with the initial benchmark scores reported by Hurtt (2010) during the scale's development.

The basis for the discipline favouring the Hurtt measure over other measures of trait skepticism goes beyond its statistical reliability and generalizability. The Hurtt measure appears to reflect the neutrality assumption of professional skepticism (Cohen et al., 2017; Quadackers et al., 2014), an assumption that is consistent with the definition of professional skepticism in the audit profession, which has guided research in operationalizing professional skepticism. Other competing measures have generally been consistent with the presumptive doubt assumption, which is generally incompatible with how the audit profession understands and communicates professional skepticism (International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board [IAASB], 2017; Lee et al., 2013).

The intent of Hurtt's measure of trait skepticism is not to discriminate between individuals with innately higher/lower levels of professional skepticism, because this has limited practical implications, but rather to better understand how their innate skepticism is then subsequently applied to audit judgment and/or audit action as state skepticism. Research has indicated that, regardless of an individual's innate level of skepticism, it is not always applied fully as state skepticism, and in some instances, the contrary has occurred. This means even individuals with higher levels of trait skepticism are not exhibiting high levels of professional skepticism in their audit actions and/or audit judgments. Therefore, it has always been the case that both research and practice are interested in achieving a stronger trait–state skepticism relationship, rather than simply distinguishing between individuals, or even discriminating individuals, on the basis of their trait skepticism (Hammersley, 2011; Hurtt et al., 2013).

With an understanding of how trait skepticism has been operationalized and measured in the literature, we now investigate the trait–state skepticism relationship to determine key drivers and determinants that can provide insight into how trait skepticism is applied as state skepticism. In the following section, an MRA is conducted on correlations reported between trait skepticism and state skepticism.

4 META-REGRESSION ANALYSIS

4.1 Approach and descriptive results

The body of literature investigating the relationship between trait and state skepticism employs a series of methods to analyse relationships, including multiple regression, Pearson correlations and ANOVA-related methods. The number of estimates from multiple regression and ANOVA-related techniques is too small to permit any meaningful quantitative meta-analysis. In contrast, 73 correlation estimates were identified, potentially providing enough information to analyse the relationship between trait and state skepticism across studies. In most cases, the studies employed controlled experimental designs, and simple correlations could thus adequately capture the relationship between trait and state skepticism without contamination by extraneous factors. In cases for which the design was such that other variables impacted the relationship, those impacts are accounted for through the MRA analysing the variation of correlations across studies (Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2012). MRA permits us to explain why the correlations differ among the studies and how this could partly be due to the variables captured by various experimental designs employed.

A total of 15 separate studies reported Pearson correlations between trait and state skepticism. Table 4 presents a descriptive summary of the papers used in the MRA. An initial inspection of the regression results and plots identified an outlier; its removal resulted in 72 separate correlation estimates from 14 studies for subsequent analysis.3 For the data analysis, given the important variability in research design among the studies, we do not employ an average or ‘best correlation estimate’ from each study. Rather, we use all the estimates and explicitly account for multiple estimates from individual studies by using research design variables and cluster error techniques.

| Paper | Independent variables | Dependent variables | Research questions | Research design | Number of tests | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghani et al. (2019) | Scepticism, self-efficacy, climate | Ethical judgment | H1: There is a significantly positive relationship between professional scepticism and ethical judgment. H2: There is a significantly positive relationship between self-efficacy and ethical judgment. H3: There is a significant relationship between ethical climate and ethical judgment. | Exploratory 2 × 1 experimental survey | 44 | H1 not supported, H2 not supported, H3 supported |

| Yustina and Gonadi (2019) | Time budget pressure, auditor independency | Scepticism | H1: Time budget pressure has a negative effect on auditor independence. H2: Auditor independence has a positive impact on professional skepticism. H3: Auditor independency mediates the relationship between time budget pressure and professional skepticism. | Exploratory survey | 27 | H1 supported, H2 supported, H3 supported |

| Rahim et al. (2019) | Professional skepticism, work experience, red flag | Fraud detection | H1: Red flags have a significant positive influence on the detection of fraud financial statement. H2: The auditor's work experience has a significant positive influence on fraud detection. H3: Auditors' professional skepticism has a significant positive influence on fraud detection. H4: Red flags have a significant positive influence on professional skepticism. H5: The auditor's work experience has a significant positive influence on professional skepticism. H6: There is a significant positive relation between red flag and fraud detection through professional skepticism. H7: There is a significant positive relation between auditor work experience and fraud detection through professional skepticism. | Exploratory survey | 24 | H1 supported, H2 not supported, H3 supported, H4 supported, H5 supported, H6 supported, H7 supported |

| Knechel et al. (2018) | Professional skepticism, firm size, certification, gender, industry experience, industry expertise, assets audited, clients audited, geographic location, Lead auditor | Income earned, audit opinion | H1a: There is no association between professional skepticism and auditor compensation. H1b: There is a positive association between professional skepticism and auditor compensation for big 4 auditors, whereas there is no association between professional skepticism and auditor compensation for non-big 4 auditors. H2a: There is a positive association between professional skepticism and audit quality. H2b: There is a positive association between professional skepticism and non-clean audit reports for non-big 4 auditors, whereas there is no association between professional skepticism and non-clean audit opinion for big 4 auditors. | Archival survey | 965 | H1a supported, H1b supported, H2a supported, H2b supported |

| Boritz et al. (2018) | Audit risk, risk propensity, order effect | Professional skepticism, inverse of trust | H1: HPSS and RITS measures provide invariant results for different audit risk assessment scenarios, when using these scales to measure the level of professional skepticism judgments, while controlling for individual level of risk propensity. H2: HPSS and RITS scales used to measure the level of professional skepticism (as the degree of neutrality versus presumptive doubt, respectively) are robust for different timings for the administration of the scales and audit scenarios, while controlling for the timing of the administration of the individual risk propensity test. H3: The timing/order in which BART is used to measure the level of the individual risk propensity should not affect the HPSS and RITS. | 3 × 2 × 2 experiment | 254 | H1 not supported, H2 supported, H3 not supported |

| Nugraha and Suryandari (2018) | Audi judgment, audit experience, experience perception, professional skepticism | Accuracy of opinion | H1: The auditor's experience positively influences opinion accuracy. H2: The auditor's experience positively affects audit expertise. H3: Experience has a positive effect on professional scepticism. H4: Experience has a positive effect on audit judgment. H5: Audit expertise has a positive effect on opinion accuracy. H6: Professional scepticism has a positive influence on opinion accuracy. H7: Audit judgment has a positive influence on opinion accuracy. H8: Audit expertise mediates the effect of experience on opinion accuracy. H9: Professional scepticism mediates the influence. H10: Audit judgment mediates the influence of experience on opinion accuracy. | Exploratory survey | 12 | H1 supported, H2 supported, H3 supported, H4 supported, H5 supported, H6 not supported, H7 supported, H8 supported, H9 not supported, H10 supported |

| Mardijuwono and Subianto (2018) | Professional skepticism, professionalism, auditor Independence | Audit quality | H1: Auditor independence is positively and significantly related to the resulting audit quality. H2: Auditor professionalism has a positive and significant impact on the resulting audit quality. H3: The auditor's professional skepticism attitude is positively and significantly related to the quality of the resulting audit. | Exploratory survey | 15 | H1 not supported, H2 supported, H3 supported, |

| Robinson et al. (2018) | Trait skepticism | State skepticism | Scale development | Exploratory survey | 75 | NA |

| Cohen et al. (2017) | Professional skepticism, inverse of trust | Perceived partner support, perceived organizational support, | H1: Auditors with higher levels of presumptive doubt PS will report lower levels of perceived partner support for PS. H2: Auditors with higher levels of neutral PS will report higher levels of perceived partner support for PS. H3: Perceived partner support for PS will be positively related to perceived organizational support. H4a: Presumptive doubt PS will have a negative indirect effect on perceived organizational support and OCB, and a positive indirect effect on turnover intention. H4b: Neutral PS will have a positive indirect effect on perceived organizational support and OCB and a negative indirect effect on turnover intention. H4c: Perceived partner support for PS will have a positive indirect effect on OCB and a negative indirect effect on turnover intention. | Exploratory survey | 80 | H1 supported, H2 supported, H3 supported, H4 supported |

| Aschauer et al. (2016) | Trust, confidence, auditor gender, firm size, client gender, auditor age, audit tenure | Professional skepticism | H: There is a positive relationship between interpersonal trust and auditor skepticism in well-functioning dyads of auditors and their respective client management. | Exploratory survey/mixed methods | 123 | H supported |

| Farag and Elias (2016) | Professional skepticism, NEO big 5, | Anticipatory socialization | H1a: There is a positive relationship between the personality characteristics of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience and trait professional skepticism among accounting students. H1b: There is a negative relationship between neuroticism and trait professional skepticism among accounting students. H2a: There is a positive relationship between the personality characteristics of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience and anticipatory socialization among accounting students. H2b: There is a negative relationship between the personality characteristic of neuroticism and the anticipatory socialization of accounting students. H3: There is a positive relationship between accounting students' levels of trait professional skepticism and their levels of anticipatory socialization. | Exploratory survey | 18 | H1 supported, H2 supported, H3 supported |

| Koch et al. (2016) | Professional skepticism, effort | Belief revision | H1: In a setting where evidence is presented sequentially and judgments are required after each piece of evidence, auditors with higher degrees of trait skepticism (particularly its evidence-related subconstruct) will exhibit fewer recency effects, compared to those with lesser degrees of trait skepticism. H2: In a setting with a complex task where evidence is presented simultaneously and judgments are asked for at the end of the evidence presentation, auditors with higher degrees of trait skepticism (particularly its evidence-related subconstruct) will exhibit greater cognitive effort mitigating the recency bias, compared to auditors with lower levels of trait skepticism. | 2 × 2 experiment | 85 | H1 supported H2 supported |

| Enofe et al. (2015) | Accounting ethics, audit experience, audit fee, audit tenure | Professional skepticism | H1: The length of auditor–client tenure has an effect on the auditor's professional skepticism. H2: The audit fee paid by the client has a significant relationship with the auditor's professional skepticism. H3: The auditor's experience has no effect on the auditor's professional skepticism. H4: The auditor's experience has an effect on the auditor's professional skepticism. | Exploratory survey | 32 | H1 supported, H2 supported, H3 supported, H4 supported |

| Quadackers et al. (2014) | Professional skepticism, inverse of trust, control environment risk | Management explanation accuracy, fraud likelihood, alternative explanations, error explanations, weight of explanations, budgeted hours | H: Presumptive doubt will be more strongly associated with auditors' skeptical judgments and decisions than neutrality, particularly when the control environment risk is higher. | 2 × 1 experiment | 98 | H supported |

| Farag and Elias (2012) | Professional skepticism, earnings management intent, earnings management | Ethical perception | H1: There is no difference in the ethical perceptions of earnings management actions based on managers' intent or type of action. H2: There are no differences in the perceptions of the ethics of earnings management based on gender, age, or class grade. H3: Individuals with greater trait professional skepticism will view earnings management actions as more unethical compared to those with lower trait skepticism. | 2 × 3 experiment | 35 | H1 not supported, H2 not supported, H3 supported |

To account for the regression error variability among studies and the use of multiple estimates from single studies in the MRA, robust and cluster-robust standard errors are employed (Angrist & Pischke, 2008). Robust standard errors capture variability through the specification of a general form of heteroscedasticity but ignore the correlation among estimates from the same study. In contrast, cluster-robust standard errors recognize both a general form of heteroscedasticity and the correlation from using estimates from the same study. Our sample contains 14 clusters, which could imply significant bias in cluster-robust standard error estimation (Angrist & Pischke, 2008, pp. 233–234). Consequently, we also report on wild bootstrap cluster-robust p-values, which have been shown to perform well with small cluster sizes (Cameron et al., 2008).

The use of multiple estimates from single studies and the recognition of subsequent error correlation among errors from the same study through cluster robust estimation techniques is now common practice in MRA studies. For example, Oczkowski and Doucouliagos (2015) examine the relation between wine prices and quality ratings using 184 estimates from 36 studies. Chaikumbung et al. (2016) use 1432 estimates from 379 studies to evaluate the economic value of wetlands, whereas Hirsch (2018) examines the persistence of firm profits using 413 estimates from 36 studies.

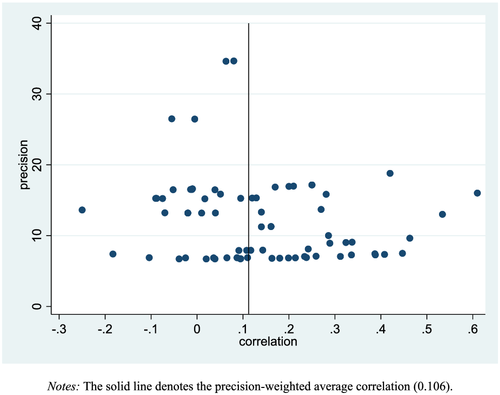

Figure 2 presents a funnel plot of the correlations, illustrating their relation to precision. Precision is measured as the inverse of the associated standard error (Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2012, p. 40). A well-developed funnel plot typically has an inverted V shape, where the estimates of the effect converge to a value with a similarly high degree of precision (Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2012, pp. 53–60). This is not obvious in our case, in which high levels of precision are associated with a variety of correlation estimates. However, consistent with the inverted V shape, the variation in correlation estimates is greater for low levels of precision. Approximately 24% (17) of the correlations are negative and 76% (55) positive. At the 5% level of significance, 6% (one of 17) of the negative correlations and 44% (24 of 55) of the positive correlations are statistically significant. The unweighted average correlation is 0.139, whereas the precision-weighted average correlation is 0.106, which is regarded as a small correlation, according to Cohen's (1988) guidelines. We can tentatively conclude, on average, that there is only a weak empirical association between trait and state skepticism.

It is potentially important to recognize that measurement scales are employed to measure the key constructs of interest. The measurement error associated with the use of multi-item scales implies that the correlations suffer from attenuation bias (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). Sufficient information has been provided in studies to correct for this bias, using Cronbach's α coefficients for trait skepticism only.4 The average of the corrected correlation estimates in unweighted form is 0.155, and the precision-weighted average is 0.118. The differences between the reported and attenuated bias-corrected averages are less than 0.02, which appears to be practically unimportant.

An important requirement of meta-analysis estimates is they be comparable. We assess data comparability by determining whether the quality of the article unduly influences the results. We test whether the correlation estimates and their precision differ according to the quality of the article. Three measures of article quality are considered: (1) the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC, at abdc.edu.au) journal quality ratings, (2) the number of Google Scholar citations and (3) the number of Google Scholar citations per year (measured from the publication year). Given that working papers are included in the data set, the measures based on journal quality ratings will not adequately reflect the quality of all articles. Additionally, any journal quality measure does not necessarily reflect the quality of any particular article in the journal. In contrast, the use of individual article citations could be considered a ‘revealed quality preference’ approach to measuring study comparability (Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2012, p. 34). The use of the total number of citations compared with the number of citations per year favours older papers, which might not necessarily be superior in quality to more recent papers. Table 5 presents estimates for the correlations and their precision and their relation to article quality measures, using various estimators that recognize error variability and correlation.

| Correlation (1) | Correlation (2) | Correlation (3) | Precision (4) | Precision (5) | Precision (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.165 | 0.117 | 0.118 | 17.38 | 15.88 | 16.96 |

| (3.91)*** | (3.81)*** | (3.32)*** | (11.6)*** | (15.3)*** | (14.9)*** | |

| [2.69]** | [2.57]** | [2.25]** | [6.14]*** | [7.40]*** | [7.68]*** | |

| {0.032}** | {0.032}** | {0.052}* | {0.000}*** | {0.000}* | {0.000}*** | |

| ABDC journal ranking | −0.010 | −2.006 | ||||

| (−0.81) | (−4.99)*** | |||||

| [−0.54] | [−2.10]** | |||||

| {0.574} | {0.058}* | |||||

| Google scholar total citations | 0.001 | −0.078 | ||||

| (1.15) | (−7.79)*** | |||||

| [1.14] | [−3.83]*** | |||||

| {0.276} | {0.002}*** | |||||

| Google scholar citations per year | 0.002 | −0.531 | ||||

| (0.86) | (−7.90)*** | |||||

| [0.79] | [−4.20]*** | |||||

| {0.454} | {0.002}*** | |||||

| R2 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.364 | 0.380 | 0.414 |

- Note: N = 72 from 14 studies. The dependent variable in columns (1) to (3) is the correlation and that in columns (4) to (6) is its precision (the inverse of the standard error). Heteroscedastic robust t-ratios are in parentheses, cluster-robust t-ratios (based on study IDs) in brackets, and wild bootstrap (based on cluster study IDs) p-values in braces.

- * Significance at the 10% level.

- ** Significance at the 5% level.

- *** Significance at the 1% level,

Table 5 suggests that the various measures of article quality do not significantly impact correlations, but they do impact precision. For precision, all three measures suggest the better the article quality, the weaker the precision of the estimates. This result is contrary to expectations, where better quality papers will tend to report more precise estimates. The reasons for this finding are not obvious but could partly be due to the absence of other important variables in these regressions. Of the three quality measures, the number of citations per year has the best explanatory power for precision, as indicated by higher R2 values and a more statistically significant estimate.

The results in Table 5 suggest that estimates in the meta-analysis dataset might not be comparable and may depend on article quality. One approach to mitigating any consequences of the non-comparability of MRA results is to include a measure of article quality as a control variable in the meta-regressions (Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2012, p. 35). Given our results, the number of citations per year will be included in subsequent analyses for the MRA.

4.2 Publication selection bias

It is important to examine whether publication selection bias influences the study results. Generally, publication selection bias is the notion that only ‘significant results’ are published. Because of the vagaries of publishing research, statistically non-significant results could be underreported in a body of literature (Roberts & Stanley, 2005). Stanley (2005, 2008) advocates a funnel asymmetry precision effect size test (FAT–PET) for publication bias. The FAT–PET involves regressing the correlations against a constant and the correlation's standard error. If there is no publication selection bias, then estimated correlations will not be correlated with their standard errors (Egger et al., 1997). In other words, publication bias exists if there is a significant correlation between the correlations and their standard errors, due to the practice of publishing significant estimates only.

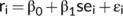

(1)

(1)The FAT–PET results are presented in Table 6. Column (1) employs the reported correlations. The results of a series of robustness checks are also presented: column (2) uses Fischer's z-transformed correlations.5 Column (3) employs the trait skepticism attenuated bias–corrected correlations. Column (4) reports on the precision effect estimate with standard error (PEESE), where se2 is used as a regressor, rather than se (Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2014). The PEESE could more accurately identify selection bias than using the standard error. In all cases, when using estimation procedures that recognize error correlation due to clustering, β0 = 0 cannot be rejected, but β1 = 0 can be rejected at the 5% level of significance. This result implies significant publication selection bias and no statistically significant effect size. In other words, the correlation between trait and state skepticism is not significantly different from zero, after the publication selection bias is recognized. The estimates in Table 6 (columns (1) to (3)) suggest a correlation effect size of approximately 0.03, which is very small.

| FAT–PET (1) | FAT–PET Fischer's z (2) | FAT–PET attenuated corrected r (3) | PEESE (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.031 | 0.033 | 0.037 | 0.074 |

| (0.86) | (0.86) | (0.93) | (2.60)** | |

| [0.72] | [0.70] | [0.76] | [1.92]* | |

| {0.488} | {0.512} | {0.494} | {0.122} | |

| Standard error | 1.136 | 1.189 | 1.089 | |

| (3.06)*** | (3.06)** | (2.89)*** | ||

| [2.71]** | [2.59]** | [2.55]** | ||

| {0.000}*** | {0.000}*** | {0.000}*** | ||

| Standard error squared | 5.777 | |||

| (2.60)** | ||||

| [2.09]* | ||||

| {0.072}* | ||||

| R2 | 0.053 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.041 |

- Note: N = 72 from 14 studies. The dependent variables in columns (1) and (4) are the Pearson correlations. In column (2), Fischer's Z transformation of the Pearson correlations is used, and in column (3), attenuated bias-corrected correlations are employed. All models are based on WLS, where the inverse values of the squared standard errors are used as weights. Heteroscedastic robust t-ratios are in parentheses, cluster-robust t-ratios (based on study ID) in brackets [], and wild bootstrap (based on cluster study ID) p-values in braces {}.

- * Significance at the 10% level.

- ** Significance at the 5% level.

- *** Significance at the 1% level,

4.3 Meta-analysis regression of trait and state skepticism correlations

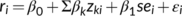

(2)

(2)The regressors proposed for Equation 2 and their summary statistics are outlined in Table 7. Three variables are employed to capture differences in research design across studies: (1) uncontrolled (vs. controlled) experiment setting, (2) student (vs. practitioner) participants and (3) low-risk (vs. high-risk or neutral-risk) environment.6 For our meta-analysis dataset, 47% of the estimates are coded as conducting the experiment in an uncontrolled environment, and 53% as conducting the experiment in a controlled environment. Student participants were employed in 22% of the cases and practitioners of various types in 78% of cases. The studies differed in the type of risk environment employed by the research design, with 17% having a low-risk environment, 44% a high-risk one and 39% a neutral-risk environment. Two variables are employed to capture differences in the measures used by the studies. For trait skepticism, 25% of the estimates used Rotter's scale, 64% employed Hurtt's measure and 11% other measures. For state skepticism, 49% of the estimates used judgment scenarios to capture this variable, whereas 51% of the estimates used action scenarios. The numbers of citations per year are also included in the MRA, with the results in Table 5, as is the possibility of article quality affecting the precision of the correlation estimates.

| Label | Definition | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect measure | |||

| Correlation | Correlation between trait and state skepticism | 0.139 | 0.171 |

| Meta-analysis regressors | |||

| Standard error | Standard error of the correlation estimates | 0.099 | 0.039 |

| Research design | |||

| Uncontrolled experiment | Design employs an uncontrolled experiment = 1, otherwise = 0 (base controlled experiment) | 0.472 | 0.503 |

| Student participants | Design employs student participants = 1, otherwise = 0 (base practitioner participants) | 0.222 | 0.419 |

| Low-risk environment | Design employs a low-risk environment = 1, otherwise = 0 (base neutral and high risk environments) | 0.167 | 0.375 |

| Measures | |||

| Rotter trait measure | Study employs the rotter trait skepticism scale = 1, otherwise = 0 (base Hurtt and other measures) | 0.250 | 0.436 |

| Judgment state measure | Study employs a judgment state skepticism measure = 1, otherwise = 0 (base action measures) | 0.486 | 0.503 |

| Citations per year | Number of Google scholar citations per year | 8.963 | 7.328 |

- Note: N = 72 from 14 studies.

The MRA estimates for Equation 2 using the regressors in Table 7 are presented in Table 8. We also considered fixed effects due to individual studies. Only the study by Cohen et al. (2017) impacted the results, and interactions between the other variables and studies also proved to be unimportant in terms of their impact on the estimates.7 Consequently, Table 8 also includes the impact of Cohen et al. (2017) on the correlation estimates. The standard WLS model results with various standard error estimates are presented in column (1). The results of four robustness checks are provided in columns (2) to (5). Column (2) uses Fischer's z correlation transformation. Column (3) corrects the correlations and their standard errors for trait skepticism measurement error. Column (4) replaces the standard error by its square, according to the PEESE procedure. Column (5) presents robust regression estimates (Rousseeuw & Leroy, 1987) that account for the impact of extreme observations.

| Variable | WLS (1) | Fischer's z WLS (2) | Attenuated corrected WLS (3) | PEESE WLS (4) | Robust regression WLS (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.025 | 0.031 | 0.037 | 0.069 | −0.010 |

| (0.25) | (0.28) | (0.36) | (0.92) | (−0.13) | |

| [0.25] | [0.28] | [0.36] | [0.88] | ||

| {0.820} | {0.796} | {0.748} | {0.444} | ||

| Standard error | 0.928 | 1.017 | 0.617 | 0.579 | |

| (0.78) | (0.79) | (0.58) | (0.68) | ||

| [0.74] | [0.75] | [0.53] | |||

| {0.482} | {0.470} | {0.602} | |||

| Uncontrolled experiment | 0.120 | 0.131 | 0.131* | 0.116 | 0.098 |

| (1.85)* | (1.85)* | (1.86)* | (1.79)* | (1.79)* | |

| [1.72]* | [1.72] | [1.73] | [1.67] | ||

| {0.140} | {0.126} | {0.150} | (0.144} | ||

| Student participants | 0.072 | 0.070 | 0.092 | 0.077 | 0.088 |

| (1.52) | (1.39) | (1.69)* | (1.74)* | (2.13)** | |

| [1.67] | [1.50] | [1.86]* | [1.87]* | ||

| {0.190} | {0.222} | {0.152} | {0.144} | ||

| Low-risk environment | −0.073 | −0.074 | −0.087 | −0.071 | −0.096 |

| (−0.88) | (−0.84) | (−0.94) | (−0.87) | (−0.94) | |

| [−1.65] | [−1.46] | [−1.78]* | [−1.76] | ||

| {0.002}*** | {0.002}*** | {0.002}*** | {0.002}*** | ||

| Rotter trait measure | −0.077 | −0.075 | −0.084 | −0.076 | −0.071 |

| (−1.78)* | (−1.63) | (−1.81)* | (−1.80)* | (−1.29) | |

| [−1.34] | [−1.24] | [−1.78]* | [−1.34] | ||

| {0.316} | {0.336} | {0.312} | {0.326} | ||

| Judgment state measure | −0.133 | −0.148 | −0.147 | −0.140 | −0.084 |

| (−1.74)* | (−1.72)* | (−1.77)* | (−1.82)* | (−1.92)* | |

| [−1.75]* | [−1.71] | [−1.77] | [−1.78]* | ||

| {0.110} | {0.108} | {0.108} | {0.116} | ||

| Citations per year | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.012 |

| (0.95) | (0.81) | (1.27) | (1.03) | (1.96)* | |

| [0.92] | [0.80] | [1.21] | [0.95] | ||

| {0.460} | {0.502} | {0.326} | {0.448} | ||

| Cohen et al. (2017) | −0.159 | −0.173 | −0.177 | −0.153 | −0.134 |

| (−2.26)** | (−2.28)** | (−2.30)** | (−2.14)** | (−2.06)** | |

| [−2.66]** | [−2.61]** | [−2.74]** | [−2.49]** | ||

| {0.44}** | {0.038}** | {0.048}** | {0.066}* | ||

| Standard error squared | 2.992 | ||||

| (0.40) | |||||

| [0.35] | |||||

| {0.690} | |||||

| R2 | 0.267 | 0.260 | 0.267 | 0.259 |

- Note: N = 72 from 14 studies. The dependent variables in columns (1), (4), and (5) are the Pearson correlations. In column (2), Fischer's Z transformation of the Pearson correlations is used, and in column (3), attenuated bias-corrected correlations are employed. All models are based on WLS, where the inverse of the squared standard errors are used as weights. Heteroscedastic robust t-ratios are in parentheses, cluster-robust t-ratios (based on study ID) in brackets [] and wild bootstrap (based on cluster study ID) p-values in braces {}.

- * Significance at the 10% level.

- ** Significance at the 5% level.

- *** Significance at the 1% level.

For the standard WLS model, the constant estimate in the MRA is 0.025, which indicates a correlation close to zero.8 The standard error and standard error squared estimates all indicate that there is no significant publication selection bias, after including the additional research design variables. This finding suggests the significant publication bias identified in Table 6 is not actually publication bias but, rather, could be due to heterogeneity in research design features across studies. Across most model types, the number of citations per year appears to be both statistically and practically unimportant in terms of their impact on the estimates. This implies that the impact of the article quality on the precision of the correlation estimates presented in Table 5 could also be due to the variation in research design and not to article quality per se.

In terms of statistical significance, the importance of variables appears to differ depending on which standard errors are employed. The use of robust standard errors suggests that uncontrolled experiments, student participants, the Rotter trait measure, the judgment state measure and the study by Cohen et al. (2017) have significant effects on the majority of alternative models. When cluster standard errors are used, statistically significant variables do not arise for the majority of models, except for the variables for student participants, the judgment state measure and the study by Cohen et al. (2017). When using the wild bootstrap clustered standard errors, only the low-risk environment and the study by Cohen et al. (2017) are statistically important. In part, the absence of statistical significance for most of the variables and the variability in results across the use of standard errors could be due to the relatively small sample size used for the MRA.

The values of the estimated coefficients are reasonably consistent across all model types and point to potentially important results. The study by Cohen et al. (2017) has the greatest impact reducing correlations by approximately 0.16, on average, across all five specifications. The use of a judgment state measure reduces the correlation between trait and state skepticism by approximately 0.13. The next largest impact occurs for uncontrolled experiments, whose use increases the correlation by approximately 0.12. The other impacts are less than 0.1 in absolute value and hence less important. The use of a low-risk environment and Rotter's trait measure in a research design both reduce the correlation by approximately 0.08, whereas the use of student participants increases it by approximately 0.08.

4.4 Discussion

The MRA of published correlation estimates in the experimental audit literature found, at best, that there was a weak positive correlation between trait and state skepticism. The unweighted average correlation is 0.14 among studies, whereas the precision weighted correlation is 0.11. Importantly. however, this association did not hold once publication bias in studies was recognized, with the correlation falling to a statistically insignificant r = 0.03, indicating no discernable correlation. In other words, there is no statistically significant or practically important relation between trait and state skepticism once the publication bias in studies has been recognized.

The findings of the meta-regression analysis identified some key drivers and determinants of the trait–state skepticism relationship that were otherwise not clearly identified (Hammersley, 2011; Nolder & Kadous, 2018) in the audit literature. The MRA results call into the question of the efficacy of capturing trait skepticism as a proxy for professional skepticism and how it is then applied in audit settings as state skepticism. Therefore, the knowledge of the key drivers and determinants of the trait–state skepticism relationship is necessary, in order for the application of trait skepticism as state skepticism to be effective in meeting audit quality standards and expectations. To address these issues and claims, this study documented the trait–state skepticism relationship in the experiment-based literature to calculate the overall average correlation in the literature to date, as well as identify this effect's key drivers. This process also involved documenting all the scales and measures used in the literature to capture trait skepticism as a construct.

The meta-analysis and meta-regression also provide some reaffirmation that the Hurtt (2010) measure is an appropriate operationalization for professional skepticism as a trait, given that it improved the strength of the trait–state skepticism relationship as opposed to alternative measures such as the inverse of Rotter's (1967) Interpersonal Trust Scale.9 However, even with the Hurtt (2010) measure, the weak relationship between trait skepticism and state skepticism is driven by contextual factors, as revealed by the MRA, which systematically impact the trait–state skepticism relationship.

One of the main findings of the MRA indicate how the student sample proves to be more effective than the practitioner sample in demonstrating a positive trait–state skepticism relationship. This finding supports the observation that student/graduate auditors tend to apply professional skepticism in a manner that is unhindered by professional experience or pressures (Farag & Elias, 2012; Farag & Elias, 2016; Peytcheva, 2014; Popova, 2012)10 This finding is useful, because it is important for the profession to not only screen new graduates with regard to qualities underlying appropriate professional skepticism but also investigate whether the profession has succeeded in providing an environment that can encourage and nurture professional skepticism.

Another finding in the meta-regression suggests audit environments where risk is high tend to induce higher levels of professional skepticism and hence strengthen the positive association in the trait–state skepticism relationship. However, in the absence of such obvious risk factors, auditors do not appear inclined to exercise appropriate professional skepticism, which weakens the positive association in the trait–state skepticism relationship (Glover & Prawitt, 2014; Payne & Ramsay, 2005). This finding is important, because the general expectation of the profession is for auditors to exercise appropriate skepticism at all times, even in the absence of obvious red flags in the audit environment (International Accounting Standards Board [IAASB], 2018). This expectation for professional skepticism also aligns with the neutrality assumption of professional skepticism (Cohen et al., 2017; Hurtt, 2010; Quadackers et al., 2014).

The meta-regression analysis also provides insight on additional variables, namely, the experiment setting (controlled vs. uncontrolled) and the manner in which state skepticism has been operationalized (i.e. as either an audit action or audit judgment), but the implications of these findings require further investigation. Regarding experiment setting, uncontrolled experiment settings appear to be capturing a stronger trait–state skepticism relationship, and the reasons for this are difficult to understand, but it is possible that uncontrolled settings allow participants to respond more freely without pressure of social desirability, given that there is far more anonymity guaranteed than in controlled settings (Dandurand et al., 2008). Regarding the operationalization of state skepticism, the MRA findings indicate that the trait–state skepticism relationship was stronger in actions than in judgments. This may be due to the fact that auditors are more likely to exercise professional skepticism when conducting actions, whereas the pressure of making a judgment often means that there are potentially other influences, such as superior/managerial preferences, which may reduce the extent to which they apply their skepticism to judgments (Carpenter & Reimers, 2013; Nelson, 2009; Noviyanti & Winata, 2015). However, this observation needs to be made carefully, as the literature moves towards better understanding how audit actions and audit judgments interact in complex audit work environments (Kadous & Zhou, 2019; Nolder & Kadous, 2018).

5 CONCLUSION

Motivated by the mixed findings in the conceptualization and operationalization of professional skepticism in audit research (Hammersley, 2011; Hurtt et al., 2013), this study conducted a meta-analysis on studies that examined the trait–state skepticism relationship using scales to measure trait skepticism as a construct. The Hurtt (2010) scale was the predominant method in the literature for measuring and operationalizing professional skepticism, and our study found 35 studies (including seven working papers) had used it to operationalize professional skepticism as trait skepticism. A descriptive analysis of the data demonstrates that the Hurtt scale has consistently and reliably measured trait skepticism across student and practitioner samples. This finding implies that, as a construct, the Hurtt scale is reliable and valid in what it is measuring. However, it is still not clear whether the construct being measured fits within the audit context as intuitively as theorized or whether the audit environment (and the manner in which it is operationalized in experimental settings) has provided a context in which trait skepticism, as a construct, can be fully applied to audit actions and audit judgments (or even measured) as state skepticism. This speculation is largely due to the mixed findings in the experimental literature regarding the size and direction of the trait–state skepticism relationship.

Following this descriptive meta-analysis, an MRA was conducted on 14 studies which examined the trait–state skepticism relationship and reported Pearson correlations. The MRA indicated a positive correlation between trait skepticism and state skepticism overall, albeit a very weak one, which did not hold once publication bias was controlled. Effectively, even though a number of studies have identified statistically important positive correlations between trait and state skepticisim, these are balanced out by other studies to result in no practically important correlation for the entire body of literature once publication bias is recognized. Reasons for the existence of positive, zero and negative correlations in the literature are provided by the key drivers and determinants identified in the MRA of the trait–state skepticism relationship. These findings are important to future research and have implications for audit practice because the audit profession encourages auditors who exhibit appropriate skeptical disposition in their actions and judgments (IAASB, 2018). However, if an auditor's inherent skeptical disposition (trait skepticism) is not strongly reflected in audit actions and audit judgments (as state skepticism), then not only has the broad discipline not fully understood the application of professional skepticism but also the audit profession could be falling short of expectations and standards when it comes to encouraging professional skepticism. An incomplete understanding of trait–state skepticism makes it difficult to identify appropriate levels of professional skepticism in practice and greatly limits the effectiveness of any efforts to encourage its application (Harding & Trotman, 2017; Nelson, 2009; Nolder & Kadous, 2018).

Despite the relatively weak trait–state skepticism relationship documented in the literature, the MRA identified important key drivers and determinants of this relationship. The findings suggest that the use of the inverse Rotter scale, compared with other trait scales, reduces the strength of the trait–state skepticism relationship, providing further evidence in favour of the Hurtt scale, which follows the neutrality assumption of professional skepticism rather than the presumptive doubt assumption of the inverse Rotter scale. The results of the meta-analysis also reaffirm the notion of how graduate/student auditors are able to exhibit and apply a given level of skepticism, one unhindered by contemporaneous factors, which can influence more seasoned auditors (e.g. the experience and pressures of their work environment and role). Finally, as Nelson (2009) also implies, a number of contemporaneous factors can influence the manner in which trait skepticism is applied in an audit setting as state skepticism. The meta-analysis reveals the level of apparent risk present in the audit environment is a factor that can increase the extent to which a given level of trait skepticism is applied as state skepticism, where higher levels of perceived risks lead to higher levels of skeptical application. However, in the absence of apparent risk, this skeptical application was weak.

Another important finding, one which also limited the meta-regression, is the analysis method employed by the professional skepticism stream of research in the audit discipline. A majority of the studies collated employed ANOVA methodology to compare skepticism between treatment conditions, and a few studies measured the effect using multiple/linear regression methods, which did not provide sufficient information for a meaningful MRA as beta coefficients would, for example, provide a meaningful statistic, which most experimental skepticism studies do not compute and/or report. These limitations not only limit the findings and conclusions that can be drawn from a meta-analysis, but also indicate how both practice and research need to understand the true effect of trait–state skepticism before drawing any conclusions and acting upon them. This would involve the investigation of regression models, as done in studies such as Quadackers et al. (2014), for example.

This MRA is timely as it provides a systematic review of the experimental professional skepticism literature published to date, and although the key finding is a weak trait–state skepticism relationship (when not controlled for publication bias), the MRA reveals a number of key drivers of this relationship, which provide some new insights and practical implications. These insights have the potential to help us understand the application of professional skepticism in audit settings, and how the literature can continue to better examine this relationship given existing methods. As a way forward, future research needs to better define professional skepticism, while better understanding and operationalizing the audit environment in experimental settings (Nolder & Kadous, 2018). Future research also needs to employ a rigorous methodology in experimental investigations of professional skepticism, ideally being able to model and measure the true effect of the trait–state skepticism relationship, through multivariate regression methods whereby meaningful conclusions can be drawn from the effect sizes (such as reporting beta coefficients). This is crucial before further developments and conclusions are drawn regarding how trait skepticism can be measured, and how it is operationalized in experimental settings to observe it as state skepticism.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the following: Angie Williamson (Faculty Liaison Librarian, Deakin University) for completing the literature search replication in 2020 for this revision; Professor Tom Stanley, Professor Chris Dubelaar and the Deakin Lab for Meta-Analysis of Research for the training and resources provided to Mohammad Jahanzeb Khan; the organizers and participants at the inaugural Auditing and Assurance for Listed and Non-Listed Entities Conference (2020) for their comments and suggestions; Carla Daws (Information Librarian & Faculty Liaison Librarian, Charles Sturt University) for completing the initial literature search in 2018; and the Research Office and Research Faculty at Charles Sturt University for the Early Career Research funding in the training of Jahanzeb Khan in Meta-Analysis via the Australian Consortium for Social and Political Research. The submitted manuscript also benefited from editorial services provided by AcademicWord, the provision of these services was supported by faculty research funding from the Faculty of Deakin Business and Law at Deakin University.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants performed by any of the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mohammad Jahanzeb Khan and Eddie Oczkowski contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, and to the writing of the manuscript.

ENDNOTES

- 1 Correlations are used because of the limited number of regression effects (betas) reported in the experimental skepticism literature, with the majority of experimental studies using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

- 2 Whenever a study reported a Hurtt skepticism mean score using a 100-point or 6-point average scale, these scores were converted to an equivalent score out of 180.