External auditors' reliance on management's experts: The effects of an early-stage conversation and past auditor–client relationship

Abstract

This study examines the impact of an early-stage conversation with a management's expert on auditors' decisions within the context of auditor–client relationships. We conducted a 2 × 2 between-subjects experiment with 69 experienced auditors in Australia. Our results suggest that an early-stage conversation can adversely affect perceived client flexibility towards proposed audit adjustments, particularly under contentious client conditions. Our results further indicate that an early-stage conversation results in auditors relaxing, which otherwise might be a more contentious approach towards difficult clients. While we do not find direct evidence that auditors succumb to pressure and accept the work of the management's expert without any changes, our results suggest that auditors are willing to propose an adjustment that meets the interests of both auditor and client.

1 INTRODUCTION

Reliance on the work of management's experts (MEs) continues to be a focus of attention for the Australian regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the audit profession. On the one hand, the use of experts continues to increase in both frequency and significance as accounting estimates become increasingly prevalent and significant in financial reporting frameworks (Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, 2019; Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, 2018). On the other hand, the ASIC continues to identify instances where auditors failed to adequately challenge, or obtain sufficient evidence to support the reasonableness of MEs' assumptions and forecasts (Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2019b, para 108).1 Such concerns are shared by public oversight boards around the world (International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators, 2020), and as a result, standard setters and professional bodies are seeking to provide additional guidance to audit practitioners. For example, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board in the United States issued a Staff Guidance, providing an overview of the new requirements in using the work of a company's specialist (Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, 2019). The Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB) further revised its Guidance Statement on the use of the work of MEs to enhance audit quality and bring consistency across audit firms (AUASB, 2020). Similarly, the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants provided additional guidance on the application of International Auditing Standards in relation to using the work of experts (South African Institute of Chartered Accountants, 2020), and Chartered Professional Accountants Canada provided a list of steps to help assurance providers to comply with the requirements in relation to using the work of an ME within the Canadian Auditing Standards (Chartered Professional Accountants Canada, 2019).

Researchers have also responded to these concerns by attempting to identify the factors that bias auditor judgement and impair audit quality. For example, prior research indicates that ME attributes, including an ME's size, experience, reputation and integrity (Goodwin, 1999; Goodwin & Trotman, 1996), proximity of an ME to the audit client (Weisner & Sutton, 2015), the sourcing of an ME (Griffith, 2015) and the degree of quantification in an ME's report (Joe, Vandervelde, & Wu, 2017) can bias auditor judgement and decisions. Researchers argue that the perceived independence of third-party MEs and a lack of knowledge about the methods and the models used by MEs may lead the auditors to focus on the information related to the expert (i.e. expert opinion heuristic) rather than the work undertaken by the ME (i.e. systematic processing). A favourable evaluation of the ME's work due to an expert opinion heuristic may thus explain inspection findings, indicating a lack of adequate audit effort (Brown-Liburd, Mason, & Shelton, 2014).

A few other studies attempt to identify factors that can potentially improve auditors' judgement and decisions in the context of using MEs' work. For example, prior literature shows that a switch of the auditors' mindset from implemental to deliberative (Griffith, Hammersley, Kadous, & Young, 2015), the presentation of data in graphical format instead of a text format (Backof, Carpenter, & Thayer, 2018), a prompt to consider regulatory concerns about the inadequate evaluation of assumptions and valuation methods (Joe et al., 2017) and an emphasis on audit quality (Pyzoha, Taylor, & Wu, 2016) can improve auditor judgement and decisions in relation to the work of MEs.2 Despite the growing attention to auditors' use of MEs' work from the regulators, standard setters, professional bodies and researchers, continually observed audit file deficiencies suggest a critical need for further research in relation to auditors' use of the work of MEs. Studies have particularly called for future researchers to identify various expert-specific, environmental, regulatory or firm-specific factors (Hux, 2017) that may influence audit planning judgements (Messier, 2010), actual audit evidence decisions (Brown-Liburd et al., 2014) and the resolution of inconsistent audit evidence (Griffith, 2015).

Our study addresses the call for additional research by investigating the impact of a regulatory factor—an ‘early-stage conversation’ between an auditor and an ME—on the auditor's judgement in the context of using MEs' work. An early-stage conversation refers to an auditor's communication with an ME as early as possible to determine if the ME's intended methodology and approach towards the task are appropriate for financial reporting purposes (GS 005, para 22). As one of the recommendations made by the new Guidance Statement GS 005 of the AUASB, the aim of having such a conversation is to improve audit quality by ensuring that all involved parties agree upon the use of the experts' work and the approach used towards its completion (GS 005, para 22). Although the Guidance Statements are recommendations and are not authoritative, whether a recommendation has achieved its intended goal is critical to the standard-setting process as monitoring of the outcomes of a standard can lead to further amendments or new standards (Boland, Brown, & Dickins, 2020).

In spite of the intended benefits of an early-stage conversation on audit quality, we propose that an early-stage conversation can have an unintended negative impact on auditors' decision-making. We argue that an early-stage conversation can increase perceived client expectation of a ‘no-surprise’ audit, which may exert more pressure on auditors. This is because a client might expect auditors to discuss and resolve all potential issues with the ME during the early-stage conversation and not to raise them once the work is completed. In the current context, we consider the client pressure as the auditors' perception of a client's flexibility towards an adjustment to the work of the ME. We examine whether having an early-stage conversation reduces auditors' perception of a client's flexibility towards an adjustment to the work of the ME.

We further examine whether having an early-stage conversation increases auditors' acquiescence to a client-preferred position. Relying on the theory of motivated reasoning, evidence from prior literature demonstrates that auditors may commit to directional goals under client pressure, provided there is ambiguity of interpretation (Blay, 2005; Ng & Tan, 2007). Given that an early-stage conversation between an auditor and an ME would increase the perceived client pressure as a result of clients' expectations of a no-surprise audit, we expect that an early-stage conversation can trigger the adoption of self-interest directional goals and consequently facilitate a greater likelihood of auditors accommodating the client's preferences.

In addition, we predict that the unintended negative impact of early-stage conversation is more pronounced under contentious auditor–client relationships. Prior research shows that auditors take a more contending position and approach towards the disposition of detected misstatements with difficult clients (Brown-Liburd & Wright, 2011; Gibbins, McCracken, & Salterio, 2010). However, when auditors perceive their bargaining power to be low (Cannon & Bedard, 2017; DeZoort, Hermanson, & Houston, 2003), they contend less, particularly when negotiating with contending clients (Brown-Liburd & Wright, 2011). The presumed credibility of an ME along with perceived auditors' failure to identify and resolve all potential issues in the early stages is likely to weaken the auditors' bargaining power and make it difficult for an auditor to argue successfully for an adjustment. This perceived difficulty may result in auditors taking a less rigid stand, particularly when negotiating with contending clients. Hence, we expect an early-stage conversation to have a greater impact on perceived client flexibility towards audit adjustments and consequently on auditors' accommodation of the client's interest under a contentious auditor–client relationship.

We conducted a 2 × 2 between-subjects factorial experiment with 69 experienced auditors in various Australian accounting firms. The dependent variables are perceived client pressure measured by perceived client flexibility to proposed audit adjustments and auditors' acquiescence to a client's interests. We manipulate the existence of an early-stage conversation (presence vs. absence) and the auditor–client relationship (collaborative vs. contentious). We find support for our initial concerns that an early-stage conversation reduces perceived client flexibility towards proposed adjustments, particularly under a contentious auditor–client relationship. Although we do not find evidence that an early-stage conversation increases auditors' acquiescence to client's interests, our findings do indicate that early-stage conversation softens auditors' contending approach towards difficult clients.

This study makes the following contributions. First, by examining the impact of an early-stage conversation on auditors' judgements, this study examines the unintended consequences of a recommendation made by the new Guidance Statement GS 005. Although the early-stage conversation is supposed to improve audit quality by bringing all parties (i.e. the ME, auditor and client) in alignment, this study provides evidence that the recommendation may not play out in the way the standard setters intended. Our findings alert audit practitioners to the potential adverse effects of early-stage conversation on audit quality and thereby highlight the need to use caution in implementing the recommendation made by GS 005.

Second, our findings add to the prior literature that examines audit settings, audit contexts and factors that meet the conditions, allowing and instigating directional reasoning by auditors through the lens of motivated reasoning (Blay, 2005; Hackenbrack, 1992; Hatfield, Jackson, & Vandervelde, 2011; Kadous, Kennedy, & Peecher, 2003; Koch & Salterio, 2017; Peecher, Piercey, Rich, & Tubbs, 2010). Our paper highlights another important condition in which an early-stage conversation with the MEs allows auditors' directional reasoning and thus softens their approach towards difficult clients. In addition, although we do not directly observe that auditors over-rely on the work of MEs in light of inconsistent audit evidence, the findings on auditors' willingness to accept an adjustment that meets auditors' minimum requirements without adversely affecting the client's interests across the treatment conditions are suggestive of motivated reasoning behaviour. Even though the extent of auditors' acquiescence to client's interests appears to be driven by reciprocity rather than an early-stage conversation, auditors continued use of motivated reasoning raises concerns about auditor independence and audit quality.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a background on the use of MEs. Section 3 discusses the hypotheses development, and Section 4 outlines the methodology. Section 5 reports the results, and Section 6 concludes by discussing the implications of the findings and providing avenues for future research.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Management's expert

The Australian auditing standard ASA 500 (identical to the equivalent International Standard on Auditing ISA 500) defines an ME as ‘an individual or organisation possessing expertise in a field other than accounting or auditing, whose work in that field is used by an entity to assist the entity in preparing the financial report’ (ASA 500, para 5e). Examples of expertise that may be classified as being provided by MEs include the valuation of complex financial instruments, land and buildings, plant and machinery, jewellery, art, intangible assets, assets and liabilities acquired in business combinations, information used for impairment assessments, estimation of resources such as oil and gas reserves, valuation of environmental liabilities, actuarial calculations, provision of engineering data required in the valuation of roads and the interpretation of contracts and laws (Agrawal, Tarca, & Woodliff, 2020; AUASB, 2020; Chartered Professional Accountants Canada, 2019; South African Institute of Chartered Accountants, 2020).

If an auditor intends to use information provided by an ME as audit evidence, then auditing standards require the auditor to evaluate the capabilities of the ME to undertake the assigned task along with the appropriateness and reasonableness of the work undertaken by the ME (ASA 500, para 8). In spite of the guidance provided by the auditing standards, the ASIC continues to find instances where the audit files did not contain sufficient evidence to support auditors' reliance on MEs [ASIC's Audit Inspection Reports issued in 2011 (para 72,74), 2012 (para 47), 2014 (para 76), 2015 (para 86), 2017 (para 90), 2019a (para 102), 2019b (para 108)]. This suggests that auditors tend to over-rely on MEs.

To address concerns raised by audit practitioners about the lack of authoritative guidance on the use of experts and their work (Bratten, Gaynor, McDaniel, Montague, & Sierra, 2013; Griffith, 2013; Griffith et al., 2015) and the regulator about auditors' over-reliance on MEs, the AUASB issued additional guidance by revising its Guidance Statement GS 005 in March 2015 and then again in March 2020.3 The latest revisions to GS 005 provide additional guidance on procedural matters in relation to determining when an individual is considered as an ME, identifying when and how management uses MEs, assessing an ME's credibility, and on issues auditors have to consider when evaluating the work of MEs (AUASB, 2020). The updates aim at enhancing audit quality in the area of the auditor's use of MEs, improving consistency among audit firms of all sizes, reflecting requirements of current and revised auditing standards [ASA 620, 2010, ASA 540, 2018b (revised), and ASA 500] and aligning the guidelines to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board amendments to the auditing standard for using the work of specialists (AS 1105, 2020, Appendix A).

2.2 Early-stage conversation

One of the recommendations made by GS 005 is for auditors to have an early-stage conversation with MEs and confirm whether the ME's intended approach and methodology is appropriate for financial reporting purposes (GS 005, para 22).4 The aim is to ensure that all involved parties agree upon the use of the ME's work and the expert's approach towards the task.

Based on interview findings, Agrawal (2018) reported that although an early-stage conversation is recommended by GS 005, auditors do not always consider it necessary to engage with the ME in the early stages. Auditors are more likely to initiate an early-stage conversation with an ME when the task is a one-off, unusual or complex. The author also reports that although the primary aim of an early-stage conversation may be to understand and to agree upon the experts' intended methodology and approach towards the task, auditors often use this opportunity to ensure that the ME understands the purpose and intended use of their work. In addition, auditors clarify their expectations regarding the extent of documentation and the depth of information required. In return, they gain insights into the ME's mindset and views regarding the assigned task. Therefore, an early-stage conversation with an ME appears to allow auditors to get a better understanding of what to expect and to raise concerns, if any, in a timely manner. Given the cost involved in engaging MEs, sorting out the issues prior to the commencement of the task is presumably beneficial to all the parties involved.

3 HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

One can assume that if auditors do have an early-stage conversation, their discussion with the ME might provide them with evidence that is either consistent or inconsistent with their expectations. Hence, to examine the full impact of an early-stage conversation on auditors' decision-making, an experimental study should examine the following three scenarios: no early-stage conversation, early-stage conversation confirming auditor expectations and early-stage conversation contradicting auditor expectations.

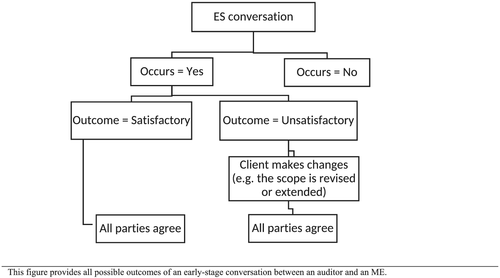

According to Agrawal (2018), if auditors do not agree to an ME's intended methodology and approach towards the valuation or they believe that the scope of the work assigned is not appropriate for financial reporting purposes, auditors are likely to raise their concerns with the client. As shown in Figure 1, the client then takes necessary action and ensures that auditor requirements are met (e.g. expand the scope of the work of the expert). Once the issue is resolved, all parties are in basic agreement, and the initial disagreement is unlikely to have a follow-up effect on auditors' judgements and decision-making. Furthermore, the interviewees in Agrawal (2018) explained that issues were rarely identified during the early-stage conversation because clients are generally knowledgeable and MEs are aware of the financial reporting requirements. Issues, if any, were largely due to a restricted or incomplete scope assigned to the ME.

Consequently, this study focuses on examining the impact of the presence or absence of an early-stage conversation on auditors' decision-making, assuming that an early-stage conversation confirms auditors' expectations. We propose that in spite of all the intended benefits of an early-stage conversation on audit planning, an early-stage conversation can also have an unintendedly negative impact on auditors' decision-making. We predict that an early-stage conversation will reduce perceived client flexibility towards auditor-proposed adjustments and, consequently, increase auditors' acquiescence to a client-preferred position.

The following paragraphs discuss the rationale behind the proposed hypothesis of an unintentional negative impact, caused by an early-stage conversation on auditors' judgement and decisions.

3.1 Impact of early-stage conversation on perceived client pressure

DeZoort and Lord (1997, p. 47) defined client pressure as ‘the pressure to yield, or the anticipation of the pressure to yield, to a client's wishes or influence whether appropriate or not’. Similarly, Brown and Johnstone (2009, p. 67) defined client pressure as the ‘extent of persuasion believed to be necessary to make the client move towards a more conservative alternative’. Prior literature identifies various economic considerations and environmental conditions that may exert pressure on auditors to acquiesce to clients' interests. For example, research finds that auditors' economic interests (Felix, Gramling, & Maletta, 2005; Hatfield et al., 2011; Trompeter, 1994); client pressure to reduce fees (Ettredge, Fuerherm, & Li, 2014; Gramling, 1999); fear of losing a client (Arnold, Bernardi, & Neidermeyer, 1999); lack of authoritative guidance (Salterio & Koonce, 1997); subjectivity of the accounting issue (Hackenbrack & Nelson, 1996); audit tenure and prior knowledge of a client's position (Brown & Johnstone, 2009; Ng & Tan, 2007; Salterio & Koonce, 1997); and perceived client flexibility (Gibbins et al., 2010; Hatfield, Houston, Stefaniak, & Usrey, 2010) can result in bias surviving the audit process. Because ‘audit firms' commercial success requires profitable audit engagements’ (Messier & Schmidt, 2018, p. 338), motivations to meet clients' expectations and accommodate their interests continue to persist.

Agrawal et al. (2020) raise concerns that MEs' perceived cognitive authority status increases the risk of insufficient scepticism exercised by auditors in seeking and evaluating audit evidence. This is because auditors tend to perceive MEs as being specialists in their field, so consequently ‘know what they are talking about’ and ‘know something that auditors do not know’. This perceived credibility of MEs enhances the reliability of the information provided by MEs (Griffith, 2015) and, thus, makes it difficult for auditors to challenge them (Cannon & Bedard, 2017). Following on from the prior literature, we argue that the inherent difficulty in persuading the client to make changes to the work of someone who is considered as an expert further increases when auditors fail to uncover the issue(s) during the early-stage conversation.

The primary purpose of an early-stage conversation is to agree on the intended methodology and basis of valuation prior to the ME undertaking the task (GS 005). Hence, it would not be unreasonable to assume that a client might expect auditors to discuss and resolve all potential issues with the ME during the early-stage conversation and not raise them once the work is completed. The anticipation that the client may not favourably look upon an auditor raising issues after the ME has completed their work will create a pressure to yield to the client's wishes of a no-surprise audit. The adverse impact of an early-stage conversation on perceived client flexibility to proposed audit adjustments presents yet another condition of client pressure that an auditor needs to withstand.

Hence, by measuring client pressure as the auditors' perception of client flexibility to an adjustment proposed to the work of the ME, we propose that

H1.Having an early-stage conversation with an ME adversely affects perceived client flexibility towards audit adjustments proposed post early-stage conversation.

3.2 Impact of an early-stage conversation on auditors' acquiescence to a client's interests

In her seminal work in social psychology, Kunda (1990) suggested that goals or motives can affect reasoning. Kunda (1990) proposed that the motivated reasoning phenomena are driven by two types of goals: accuracy and directional. When people are motivated to be accurate, they are likely to put more cognitive effort into issue-related reasoning, attend to information more carefully and process it more deeply (Kunda, 1990). When people are motivated to arrive at a desired conclusion, they attempt to construct a reasonable justification for their preference. In other words, their belief construction, evidence collection and evaluation become biased by directional goals (Kunda, 1990). Kunda (1990) argued that motivated reasoners make self-interested goal-consistent judgements but they are subject to the ‘reasonableness constraint’. That is, they cannot display unrestrained self-interest but attempt to be rational and construct a justification for their desired conclusion that would persuade a ‘dispassionate observer’.

Both the accuracy and directional goals are present in an audit context. Auditors are responsible for ensuring that a client's financial statements are free from material misstatement to warrant an unqualified audit opinion. Failure to provide an appropriate (‘accurate’) audit opinion may result in disciplinary actions against the firm (Lennox & Li, 2020) and cause reputational damage to both the audit firm and its clients (Chaney & Philipich, 2002; Davis & Simon, 1992; Dechow, Ge, & Schrand, 2010; Dechow, Sloan, & Sweeney, 1996; Wilson & Grimlund, 1990). Hence, auditors' actions and decisions will be driven by accuracy goals. However, research also indicates that in an auditor–client relationship, auditors are the relationship managers whose job is also to see that the client remains ‘happy’ (McCracken, Salterio, & Gibbins, 2008). The damage that a confrontation would cause to the auditor–client relationship and client retention exposes auditors to directional goals and may result in introducing a subconscious bias into auditors' judgements, decisions and actions. The ‘reasonableness’ criteria would however require auditors to be able to justify their decision as being unbiased and reasonable.

Consistent with the theory of motivated reasoning, Blay (2005) found that auditors' interpretation of information related to issues of going concern aligns with management when they perceive a threat of losing the engagement. Similarly, Hackenbrack and Nelson (1996) observed that auditors interpret accounting standards to justify a client's aggressive financial reporting. Ng and Tan (2007) found that auditors' propensity to insist on an adjustment is reduced in the presence of expressed client concerns, particularly when the audit difference is subjective and the auditors' decision to acquiesce to the client can be reasonably justified. Various archival studies also provide evidence that auditors are more likely to accept client-preferred outcomes (i.e. driven by directional goals) when the audit difference is subjective (Braun, 2001; Libby & Kinney, 2000; Nelson, Elliott, & Tarpley, 2002; Ng, 2007; Wright & Wright, 1997). The subjectivity involved not only provides an opportunity to rationalise the client's preference but also makes it difficult for auditors to define what is reasonable and appropriate and, consequently, justify and insist on an adjustment.

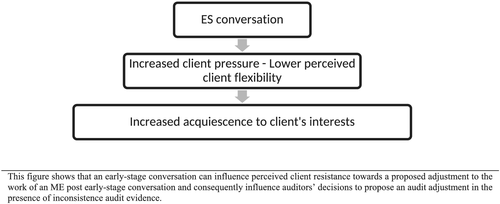

As noted earlier, an early-stage conversation allows auditors to work with the ME and to confirm whether the ME's intended approach and methodology is appropriate for financial reporting purposes. A satisfactory early-stage conversation will consequently assist the auditor in planning the audit. It is also reasonable to assume that a client might expect auditors to discuss and resolve all potential issues with the ME during an early-stage conversation and not raise them once the work is completed. Taken together, a subjective audit difference, perceived high capabilities of an ME and perceived pressure to yield to the client's expectations of a no-surprise audit (because of an early-stage conversation) may weaken an auditor's relative bargaining power. Other things being equal, this may reduce the likelihood of auditors succeeding in a negotiation. As depicted in Figure 2, this may trigger the adoption of self-interest directional goals (e.g. preventing confrontation and keeping the client happy) that facilitate a greater likelihood of auditors accommodating the client's preferences, provided that support for the decision can be reasonably provided.

Accordingly, we propose that

H2.Auditors are more likely to acquiescence to a client's interests when auditors had an early-stage conversation with the ME, compared with when auditors did not have such an early-stage conversation with the ME.

3.3 Auditor–client relationship

Auditor–client negotiations are not a one-time occurrence (Beattie, Fearnley, & Brandt, 2000; Gibbins, Salterio, & Webb, 2001). Past experiences with a client will allow auditors to predict how a particular client is likely to react to a proposed adjustment and be better prepared for the negotiation (Brown & Wright, 2008; Brown-Liburd & Wright, 2011; Gibbins & Salterio, 2000; Trotman, Wright, & Wright, 2005). When an auditor faces the prospect of negotiating with a difficult and contentious client, the auditor is likely to anticipate that the client will challenge the auditor's position and strongly object to any adjustment proposed. However, as a relationship manager, it is the role of the auditor to come up with strategies to negotiate (Hatfield, Agoglia, & Sanchez, 2008), determine appropriate persuasion tactics (Perreault & Kida, 2011), develop potential solutions that will satisfy the client, ensure at least minimum compliance to the GAAP and maintain the ongoing relationship with the client (McCracken et al., 2008). Accordingly, many researchers have investigated the impact of the auditor–client relationship on the negotiation process. For example, a past auditor–client relationship can influence auditors' pre-negotiation planning (Brown-Liburd & Wright, 2011), auditors' negotiation strategies (Brown-Liburd & Wright, 2011; Fu, Tan, & Zhang, 2011; Gibbins et al., 2010; Hatfield et al., 2008) and the eventual outcome of negotiations (Fu et al., 2011; Gibbins et al., 2001; Ng & Tan, 2003).

Evidence from prior literature suggests that auditors generally adopt a reciprocity approach when dealing with clients. Accordingly, studies examining auditor–client negotiations find that auditors take a contending approach with difficult clients by making higher initial offers and making fewer concessions during the negotiation. A contentious approach adopted by a client during past negotiations results in auditors forming a negative perception about the client (Rennie, Kopp, & Lemon, 2010), thereby resulting in auditors taking a tougher stand (Pruitt & Carnevale, 1993). Further, a tougher stand during negotiation legitimises the professional role of auditors in the eyes of the client (Bame-Aldred & Kida, 2007; Beattie, Fearnley, & Brandt, 2004; Beattie, Fearnley, & Hines, 2015), sets the tone for future negotiation (Emby & Favere-Marchesi, 2010; Gibbins et al., 2001; Kleinman & Palmon, 2000) and prevents future exploitation by the counterparty (Roering, Slusher, & Schooler, 1975). However, when auditors perceive their bargaining power to be low due to a weak audit committee, ambiguous accounting standards or estimation uncertainties (Cannon & Bedard, 2017; DeZoort et al., 2003), auditors are found to contend less by adopting a more accommodating approach when negotiating with contending clients (Brown-Liburd & Wright, 2011; Ng & Tan, 2003).

Following on from the prior research, we expect that a client's expectation of a no-surprise audit adds additional pressure on auditors, which may lower their perceived bargaining power. Consequently, to protect their own self-identity that they have professional expertise and did not err in the past by not resolving all potential issues during the early-stage conversation, it is likely that auditors' acquiescence to the client's interests will be more pronounced when the past auditor–client relationship is contentious. In contrast, if the past experiences with a client suggest that the client is collaborative and receptive, it is likely that the client will continue to work with the auditors openly on contentious issues, irrespective of the early-stage conversation. Due to the amenable nature of the client, we expect an early-stage conversation to have a smaller impact on perceived client flexibility towards audit adjustments and, consequently, on auditors' accommodation of the client's interest.

Consequently, we propose that

H3.An early-stage conversation with an ME has a larger adverse effect on auditors' perceived client flexibility when the client is contentious than when the client is collaborative.

H4.An early-stage conversation with an ME has a larger effect on auditors' acquiescence to a client's interests when the client is contentious than when the client is collaborative.

4 RESEARCH METHOD

To examine the impact of an early-stage conversation on perceived client pressure and auditors' acquiescence to a client's interests, this study employs a 2 × 2 between-subjects factorial experimental design with independent variables: (i) early-stage conversation (present vs. absent) and (ii) auditor–client relationship (collaborative vs. contentious).

4.1 Sample and administration

Participants were drawn from eight accounting firms, including both Big 4 and non-Big 4 firms located in Australia.5 An invitation letter with a link to the experiment was sent to audit partners for distribution. The invitation letter explicitly requested participation only from auditors who had experience in evaluating the work of experts (preferably manager level and above). Participation was voluntary, and participants were offered $50 upon completion of the experiment.6 Qualtrics, the online data collection software, was used to collect data. Qualtrics allocated a participant randomly into one of the four treatments.

Data were collected over a period of 7 months from September 2016 to March 2017. Out of the 95 responses recorded by Qualtrics, 26 were removed from the sample as they were either incomplete or did not demonstrate sufficient attention to detail. Accordingly, the results reported henceforth are based on the final 69 observations.

Demographic data are reported in Table 1. Among the 69 participants, 57.97% were from the Big 4 accounting firms, and 62.32% were male. Participants had an average of 9.55 years of experience in the field of audit and assurance (standard deviation = 5.57), and 72.46% of them were less than 35 years of age. The majority of participants were manager level or above and were regularly involved in evaluating the work of experts.7

| Employment | |

|---|---|

| Type of employer (frequency and percentage) | |

| • Big 4 accounting firms | 40 (57.97%) |

| • Non-Big 4 accounting firms | 29 (42.03%) |

| • Total | 69 (100%) |

| Professional designation (frequency and percentage) | |

| • Senior (audit) | 1 (1.45%) |

| • Assistant manager (audit) | 3 (4.35%) |

| • Manager (audit) | 30 (43.48%) |

| • Supervisor (audit) | 1 (1.45%) |

| • Senior manager (audit/advisory services) | 7 (10.14%) |

| • Associate director (audit) | 4 (5.80%) |

| • Director (assurance) | 9 (13.04%) |

| • Partner (audit) | 6 (8.70%) |

| • Other (accountant, senior accountant, advisor and senior analyst) | 7 (10.14%) |

| • Unknown (information not provided) | 1 (1.45%) |

| • Total | 69 (100%) |

| Gender (frequency and percentage) | |

| • Male | 43 (62.32%) |

| • Female | 26 (37.68%) |

| • Total | 69 (100%) |

| Age (frequency and percentage) | |

| • Below 35 | 50 (72.46%) |

| • 36–44 | 16 (23.19%) |

| • 45–54 | 2 (2.90%) |

| • Over 55 | 1 (1.45%) |

| • Total | 69 (100%) |

| Experience: Audit and assurance (years) | |||||

| • Overall mean and standard deviation | 9.55 (5.57) | ||||

| • Distribution (frequency and percentage) | |||||

| • Up to 5 years | 11 (15.94%) | ||||

| • 5.1–10 years | 37 (53.62%) | ||||

| • 10.1–15 years | 12 (17.39%) | ||||

| • Over 15 years | 9 (13.04%) | ||||

| • Total | 69 (100%) | ||||

| • Number of years with current employer | |||||

| • Overall mean and standard deviation | 6.64 (4.92) | ||||

| • Number of years in the current position | |||||

| • Overall mean and standard deviation | 2.86 (3.47) | ||||

| Experience: Task specific (frequency and percentage) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequently | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Total | |

| Evaluation of a client's impairment testing | 41 (59.42%) | 19 (27.54%) | 7 (10.14%) | 2 (2.90%) | 69 (100%) |

| Evaluation of the reliability of the work of a client's expert | 31 (44.93%) | 30 (43.48%) | 6 (8.70%) | 2 (2.90%) | 69 (100%) |

| Engaged in discussions pertaining to audit adjustments with a client | 56 (81.16%) | 9 (13.04%) | 2 (2.90%) | 2 (2.90%) | 69 (100%) |

| Insisted on a material adjustment to the financial statements | 26 (37.68%) | 30 (43.48%) | 10 (14.49%) | 3 (4.35%) | 69 (100%) |

- Note: This table provides information on the demographics of the 69 participants whose responses have been analysed in the study.

4.2 Experimental task

The experimental instrument required participants to evaluate the work done by an ME engaged by an audit client and make decisions pertaining to the acceptability of the work of the ME as audit evidence. The instrument used in this study was developed in consultation with two audit directors from a Big 4 accounting firm, who identified ‘impairment’ as a key audit issue that is worth examining.8 The discussions with the audit directors also informed the setting that could provide an opportunity for auditors to acquiesce to a client's interests without compromising their own self-interest. Feedback on the draft instrument was sought from five renowned academics in the field, one audit practitioner and two technical advisers with a Big 4 accounting firm. Consequently, the terminology used in the experiment, the content and the wording of the manipulations, the placement of the information and the overall layout of the experiment were modified. The revised instrument was later pilot tested with academics within the discipline of accounting, and minor changes were made. The above process ensured that the task developed was clear, realistic and well designed.

The case began by providing participants with a background description of a hypothetical medium sized listed company in Australia. The case informed participants that the company had undertaken an impairment test with the help of a third-party expert. The audit evidence obtained by the audit team indicated that the third-party expert was a credible information source and all assumptions, except the discount rate used in the discounted cash flow model, were considered reasonable.

The third-party expert estimated the discount rate at between 10% and 12% and had used 10.8% in the computation of the recoverable amount of the client's operations. Other evidence such as the recommended range for discount rates by the audit firm's internal valuation division (11%–13%) and the average discount rate used by comparable companies (11.8%) implied a potential under-estimation of risk by the client's expert. Sensitivity analysis indicated that a discount rate of 11.2% would trigger an impairment charge, which if recognised would materially impact the client's financial statements. Overall, the audit evidence suggested that a small adjustment to the discount rate (i.e. increase of discount rate from 10.8% to either 11% or 11.1%), if insisted by the auditor would ensure that the client met with at least the lowest recommended discount rate without any materially adverse impact on their financial statements. However, any upward movement in the discount rate (i.e. from 11.2% onwards) would result in recognition of an impairment charge and therefore require a material adjustment to the financial statements. Importantly, the case provided an audit setting that provides some room for ambiguity of interpretation (i.e. an opportunity for auditors to accept the client's position without compromising their self-interests). Consistent to the motivated reasoning theory, by proposing a discount rate of 11% or 11.1%, auditors will not only be able to arrive at a desired conclusion (i.e. safeguard their client's interests by not requiring an impairment which will adversely affect the client's financial interests) but will also be able to reasonably justify their decision (i.e. the proposed adjustment ensures that the discount rate is within the range recommended by the audit firm's internal valuation division). Other risk factors were controlled, and the narrative deliberately kept generic to prevent potential noise that additional factors could bring to the setting.

After reading the above information, participants (1) assessed client flexibility to a proposed adjustment to the work of the ME (i.e. perceived client pressure) and (2) made decisions regarding the acceptability of the ME's work (i.e. acquiescence to the client's interests). Participants then went through manipulation checks, provided demographic information and lastly reflected upon their own personal experience with MEs at the end of the instrument.

4.3 Dependent variables

4.3.1 Perceived client pressure–perceived client flexibility (FLEXIB)

The first dependent variable assesses if an early-stage conversation increases perceived client pressure. We argue that an early-stage conversation will increase client expectations of a no-surprise audit and hence adversely affect auditors' perceptions of client flexibility towards an adjustment proposed post early-stage conversation. Accordingly, we operationalise perceived client pressure as the extent of perceived client flexibility towards any proposed audit adjustment to the ME's work. Participants were asked ‘If you were to propose an adjustment to the discount rate, how likely is it that the client would be willing to accept your recommendation and recognise an impairment of its assets?’ Responses were measured on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = being extremely unlikely to 5 = being neutral to 10 = being extremely likely. A higher rating suggests a higher perceived client flexibility and, hence, a lower perceived client pressure.

4.3.2 Acquiescence to client's interests

The second dependent variable measures auditors' acquiescence to client's interests by either accepting the work of an ME without proposing any adjustment or by requiring goal-consistent adjustments that are within reasonable constraints and meet both auditor and client interests. These two measures are discussed below.

Accept the work of an ME (ACCEPT)

The first measure, ACCEPT, requires participants to assess the likelihood of them accepting the work of the client's expert with no changes. Participants responded on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = extremely unlikely, 5 = neutral and 10 = extremely likely). A participant's decision to accept the work of an ME without any changes is justifiable as discount rate estimations are subjective. Hence, the ME's estimated discount rate can be considered reasonable, unless the potential misstatement resulting from an alternative discount rate is highly material or there is a strong reason to be concerned about the ME's work. In addition, an adjustment to the discount rate from 10.8% to 11% or 11.1% would not result in an impairment. Consequently, proposing an immaterial adjustment would have no merit. Hence, the dependent variable, ACCEPT, indicates the auditors' willingness to accept the work of an ME in the presence of subjective inconsistent audit evidence.

Insist on an impairment (IMPAIR)

The second measure, IMPAIR, is a binary variable and used to reveal the proportion of auditors who will insist on an impairment. Participants were asked to indicate the lowest discount rate they would be willing to accept and give an unqualified audit opinion (MINIMUM). Participants were provided with a selection ranging from 9.5% to 13.5% and were asked to move the slider to their preferred position. If a participant indicates the minimum acceptable discount rate to be equal to or greater than 11.2%, then the dependent variable, IMPAIR, takes the value of ‘1’, otherwise ‘0’. As the minimum acceptable position of an auditor indicates the sacrifice an auditor would be willing to make in order to reach an agreement, a more compromising approach would be implied if participants indicated their willingness to accept a discount rate of lower than 11.2%.

4.4 Independent variables

Two independent variables (early-stage conversation and auditor–client relationship) are manipulated between participants resulting in a 2 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) design. The manipulation of an early-stage conversation (ES) with an ME refers to the presence or absence of the early-stage conversation and is consistent with its stated purpose by the auditing standards. According to GS 005, communication with an ME as early as practicable during the engagement would allow an opportunity to the auditor to confirm whether the ME's intended approach and methodology is appropriate for financial reporting purposes (GS 005, para 22). The manipulation of auditor–client relationship (RELATION) differentiates a collaborative and cordial client from a difficult and contentious one.9 Consistent with the elements used by Hatfield et al. (2008) and Brown-Liburd and Wright (2011) to describe auditor–client relationships, this study manipulates the relationship by focusing on two characteristics: (1) auditor–client interactions in the past and (2) flexibility of the client towards proposed audit adjustments in the past. See Figure 3 for a description of the wording of the manipulated variables.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Manipulation and other checks

Two manipulation check questions were employed.10 For the auditor–client relationship condition, participants were asked, ‘What do you think best describes the past relationship your audit firm has had with the CFO when dealing with proposed audit adjustments?’ Responses were recorded on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = extremely difficult; 10 = extremely cooperative). The average rating of participants in the contentious-client condition is significantly lower than those in the collaborative-client condition (means = 1.90 and 8.34 respectively, p < 0.001), suggesting this manipulation was perceived as desired.11

To check if participants recognised the presence or the absence of an early-stage conversation, participants were asked to indicate if the audit manager within the case material had an early-stage conversation with the client's expert. Three options were provided: Yes, No and Unsure. Five participants answered incorrectly, and three were unsure of the condition. Possibly, the participants considered the information obtained through the early-stage conversation as immaterial, hence, the lack of attention to detail.12

Participants were also asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed that the case material realistically represented a situation they might come across during the course of an audit. The participants answered on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = completely disagree, 5 = neutral and 10 = completely agree). The mean response (standard deviation) was 8.04 (1.499). This indicates that overall, participants considered the case to be realistic.

5.2 Test of hypotheses

5.2.1 Test of H1 and H3 on perceived client pressure (inferred from perceived client flexibility)

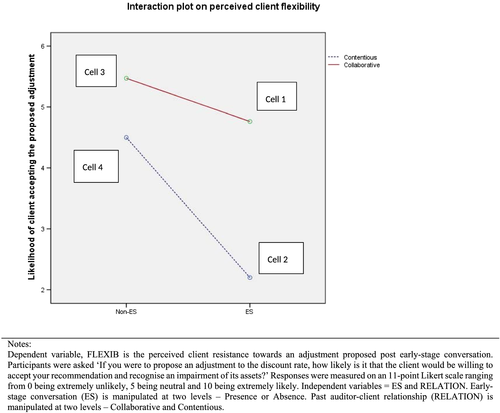

A two-way ANOVA is performed to test if early-stage conversation influences auditors' perception of client flexibility to an adjustment proposed after the completion of the ME's work.13 As reported in panel A of Table 2, perceived client flexibility (FLEXIB) is lower under ES conditions (mean = 3.457) as compared with non-ES conditions (mean = 5.011). This result supports H1 that having an early-stage conversation with an ME reduces perceived client flexibility towards audit adjustments proposed in later stages. Our results also indicate that collaborative clients are perceived to be relatively more flexible (mean = 5.121) towards proposed adjustments than contentious clients (mean = 3.346). A two-way ANOVA indicates significant main effects for both early-stage conversation (F = 8.842, p = 0.002, one-tailed) and auditor–client relationship (F = 12.188, p = 0.001, one-tailed) confirming that perceived client flexibility is significantly lower when clients are considered contentious and when auditors have an early-stage conversation with MEs (refer panel B of Table 2).

| Panel A: Means (standard error) for perceived client flexibility towards a proposed adjustment to the work of the ME by treatment conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | Non-ES | Overall | |||

| Collaborative |

4.743 (0.458) N = 21 Cell 1 |

5.499 (0.509) N = 17 Cell 3 |

5.121 (0.341) N = 38 |

||

| Contentious |

2.170 (0.542) N = 15 Cell 2 |

4.522 (0.524) N = 16 Cell 4 |

3.346 (0.376) N = 31 |

||

| Overall |

3.457 (0.355) N = 36 |

5.011 (0.366) N = 33 |

4.234 (0.254) N = 69 |

||

| Panel B: Test of hypothesis by treatment conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p-value (one-tailed) |

| Corrected model | 94.541 | 3 | 31.514 | 7.252 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | 1216.885 | 1 | 1216.885 | 280.046 | 0.000 |

| ES | 38.42 | 1 | 38.42 | 8.842 | 0.002 |

| RELATION | 52.963 | 1 | 52.963 | 12.188 | 0.001 |

| ES*RELATION | 10.748 | 1 | 10.748 | 2.473 | 0.061 |

| Error | 282.445 | 65 | 4.345 | ||

| Corrected total | 376.986 | 68 | |||

| R2 = 0.251 (adjusted R2 = 0.216) | |||||

| Panel C: Ordinal interaction contrast coding test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned contrast | t-statistic | p-value (one-tailed) | |||

| (+3, −1, +2, −4) | 1.833 | 0.036 | |||

- Note: Dependent variable, FLEXIB, is perceived client resistance towards an adjustment proposed post early-stage conversation. Participants were asked, ‘If you were to propose an adjustment to the discount rate, how likely is it that the client would be willing to accept your recommendation and recognise an impairment of its assets?’ Responses were measured on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = being extremely unlikely, 5 = being neutral and 10 = being extremely likely. Independent variables = ES and RELATION. Early-stage conversation (ES) is manipulated at two levels: presence or absence. Past auditor–client relationship (RELATION) is manipulated at two levels: collaborative and contentious.

- Abbreviation: MEs, management's experts.

To test if the adverse impact of early-stage conversation on perceived client flexibility was more pronounced under contentious auditor–client relationship (H3), we conduct a planned contrast test. Buckless and Ravenscroft (1990) suggested that contrast coding provides greater statistical power than the conventional ANOVA when examining ordinal interactions. We test if the mean difference in perceived client flexibility towards an audit adjustment between the ES-Contentious condition (cell 2) and non-ES-Contentious condition (cell 4) is greater than the mean difference between ES-Collaborative condition (cell 1) and non-ES-Collaborative condition (cell 3). As a result, the following contrast weights are used to examine the ordinal interaction: ES-Collaborative condition (cell 1 = +3), ES-Contentious condition (cell 2 = −1), non-ES-Collaborative condition (cell 3 = +2) and non-ES-Contentious condition (cell 4 = −4).14 The results from the planned contrast test (refer to panel C of Table 2) and the downward slopes shown in Figure 4 support our predictions in H3, that is, an early-stage conversation lowers perceived client flexibility and that the size of the effect is larger for contentious clients. See Figure 4 for a graphical presentation of the impact of the independent variables on perceived client flexibility.15

5.2.2 Test of H2 and H4 on acquiescence to client's interests

Accept the work of an ME (ACCEPT)

Auditors' acquiescence to client's interests is primarily measured by the likelihood of auditors' accepting the work of the ME without any changes (ACCEPT). We conduct a two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to examine the effects of an ES and RELATION on ACCEPT. Participants' total audit experience (EXP) is included as a covariate.16 Descriptive statistics across treatment conditions, and the results for the ANCOVA are reported in panels A and B of Table 3, respectively.

| Panel A: Means (standard error) for the likelihood of auditors accepting the work of the ME by treatment conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | Non-ES | Overall | |||

| Collaborative |

3.530 (0.396) N = 21 Cell 1 |

3.003 (0.441) N = 17 Cell 3 |

3.267 (0.296) N = 38 |

||

| Contentious |

2.935 (0.469) N = 15 Cell 2 |

2.486 (0.454) N = 16 Cell 4 |

2.711 (0.326) N = 31 |

||

| Overall |

3.233 (0.469) N = 36 |

2.745 (0.317) N = 33 |

2.989 (0.220) N = 69 |

||

| Panel B: Test of hypothesis by treatment conditions (two-way ANCOVA) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p-value (one-tailed) |

| Corrected model | 21.901 | 4 | 5.475 | 1.668 | 0.084 |

| Intercept | 226.309 | 1 | 226.309 | 68.957 | 0.000 |

| ES | 3.963 | 1 | 3.963 | 1.208 | 0.138 |

| RELATION | 5.242 | 1 | 5.242 | 1.597 | 0.106 |

| ES*RELATION | 0.026 | 1 | 0.026 | 0.008 | 0.465 |

| EXP | 9.981 | 1 | 9.981 | 3.041 | 0.043 |

| Error | 210.041 | 64 | 3.282 | ||

| Corrected total | 231.942 | 68 | |||

| R2 = 0.094 (adjusted R2 = 0.038) | |||||

| Panel C: Ordinal interaction contrast coding test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned contrast | t-statistic | p-value (one-tailed) | |||

| (+3, −1, +2, −4) | 1.589 | 0.059 | |||

- Note: Dependent variable, ACCEPT, is the likelihood of auditors accepting the work of the client's expert with no changes. Participant responses were measured on an 11-point Likert scale where 0 = extremely unlikely, 5 = neutral and 10 = extremely likely. A lower assessment suggests that auditors are less likely to accept the work of an ME in the presence of inconsistent audit evidence. That is, auditors are more likely to propose an adjustment. Independent variables = ES and RELATION. Early-stage conversation (ES) was manipulated at two levels: Presence or Absence. Past auditor–client relationship (RELATION) was manipulated at two levels: Collaborative and Contentious. Covariate (EXP) is participants' experience in the field of audit and assurance. Experience was measured by the number of years.

- Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; MEs, management's experts.

As shown in panel A of Table 3, the mean acceptance of the client's position is less than ‘5’ across all of the four treatments. This indicates that overall, auditors are unlikely to accept the work of the ME without an adjustment. Consistent with our expectations, the pattern of cell means reveals that the presence of an early-stage conversation has a positive impact on auditors' acceptance decision (mean for ES condition = 3.233 and for non-ES condition = 2.745) under both collaborative and contentious auditor–client conditions. However, the insignificant main effect of early-stage conversation on auditors' acceptance decisions indicates that the impact of early-stage conversation is not statistically significant (refer to panel B: F = 1.208, p = 0.138, one-tailed). Similarly, the relative likelihood of auditors accepting the work of an ME appears to be higher when auditors have a collaborative relationship with their clients (mean acceptance likelihood for collaborative clients = 3.267 and for contentious clients = 2.711). However, the insignificant main effect of RELATION on auditors' acceptance decisions also indicates that the impact of the auditor–client relationship is not statistically significant (refer to panel B: F = 1.597, p = 0.106, one-tailed). These findings imply that in the presence of inconsistent audit evidence, auditors are unlikely to accept the work of an ME without any changes.17 The presence of an early-stage conversation will not influence their decision to propose an adjustment. The findings do not support H2.18

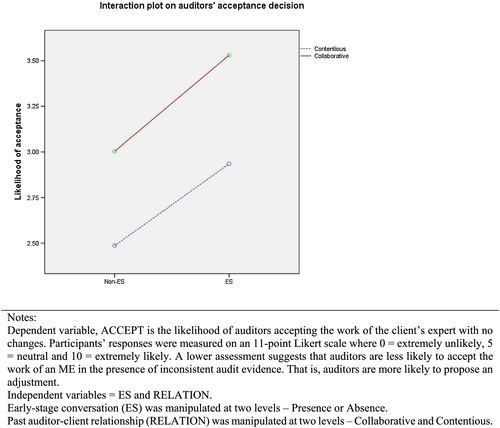

We conduct a planned contrast to test the impact of an early-stage conversation on the auditors' acceptance decisions for both collaborative and contentious clients (H4). As shown in panel C of Table 3, the presence of an early-stage conversation does not have a significantly larger effect on auditors' decisions to accept the work of the ME when the auditor–client relationship is contentious (t = 1.589, p = 0.059). The interaction plot shown in Figure 5 confirms that the size of impact of early-stage conversation on auditors' acceptance of the work of MEs does not differ due to the auditor–client relationship, suggesting that H4 is not supported.

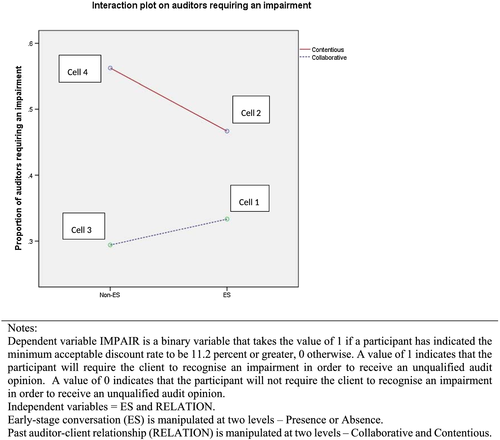

Insist on an impairment (IMPAIR)

The second measure of auditors' acquiescence to clients' interests is auditors' willingness to insist on an impairment—IMPAIR. Table 4 reports the frequency statistics for the variable MINIMUM. As shown in panels A and B of Table 4, the raw scores for MINIMUM (i.e. the minimum acceptable discount rate indicated by the participants) across the four treatments are not significantly different from each other (F = 0.886, p = 0.453). However, a frequency table based on auditors' indications of the minimum acceptable discount rate for an unqualified audit opinion (refer to panel C of Table 4) shows that only 40.6% of the participants actually insisted on an impairment. Participants' willingness to accommodate the client's financial interests by not insisting on impairment is suggestive of the auditors' acquiescence to clients' interests.

| Panel A: Means (standard error) for minimum discount rates required by auditors by auditors by treatment conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | Non-ES | Overall | |||

| Collaborative |

11.148 (0.090) N = 21 Cell 1 |

11.141 (0.100) N = 17 Cell 3 |

11.144 (0.067) N = 38 |

||

| Contentious |

11.34 (0.106) N = 15 Cell 2 |

11.256 (0.103) N = 16 Cell 4 |

11.298 (0.074) N = 31 |

||

| Overall |

11.244 (0.070) N = 36 |

11.199 (0.072) N = 33 |

11.213 (0.049) N = 69 |

||

| Panel B: Test of differences between cell means (one-way ANOVA) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p-value | |

| Between groups | 0.449 | 3 | 0.15 | 0.886 | 0.453 |

| Within groups | 10.989 | 65 | 0.169 | ||

| Total | 11.438 | 68 | |||

| Panel C: Distribution of participants by minimum discount rate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discount rate (%) | Frequency | Per cent | Cumulative Per cent | ||

| 10.00 | 1 | 1.40 | 1.40 | ||

| 10.80 | 5 | 7.20 | 8.70 | ||

| 11.00 | 35 | 50.70 | 59.40 | ||

| 11.20 | 4 | 5.80 | 65.20 | ||

| 11.30 | 2 | 2.90 | 68.10 | ||

| 11.40 | 1 | 1.40 | 69.60 | ||

| 11.50 | 11 | 15.90 | 85.50 | ||

| 11.80 | 8 | 11.60 | 97.10 | ||

| 12.00 | 1 | 1.40 | 98.60 | ||

| 13.00 | 1 | 1.40 | 100.00 | ||

| Total | 69 | 100.00 | |||

- Note: Panel A reports the cell means of the minimum discount rates indicated by the participants across the four experimental conditions. Panel B reports the results of one-way ANOVA with minimum discount rate as the dependent variable and the four treatment cells as the independent variables. Panel C reports the frequency table for participants' selection of the minimum discount rate.

- Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Based on the raw scores of MINIMUM, we create a binary variable IMPAIR to measure whether the auditor is willing to insist on an impairment. By design, if a participant indicates the minimum acceptable discount rate to be equal to or greater than 11.2%, then the dependent variable, IMPAIR, takes the value of ‘1’, otherwise ‘0’. Table 5 provides the results of the binary logistic model.19

| Panel A: Proportion (standard error) of auditors likely to insist on an impairment by treatment conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ES | Non-ES | Overall | |

| Collaborative |

33.3% (0.108) N = 21 Cell 1 |

29.4% (0.120) N = 17 Cell 3 |

31.6% (0.079) N = 38 |

| Contentious |

46.7% (0.128) N = 15 Cell 2 |

56.3% (0.124) N = 16 Cell 4 |

51.6% (0.088) N = 31 |

| Overall |

38.9% (0.083) N = 36 |

42.4% (0.087) N = 33 |

40.6% (0.060) N = 69 |

| Panel B: Test of hypothesis by treatment conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalised linear model (function-logit, distribution-binomial) | |||

| Source | Wald χ2 | df | p-value (one-tailed) |

| Intercept | 2.065 | 1 | 0.076 |

| ES | 0.040 | 1 | 0.421 |

| RELATION | 2.790 | 1 | 0.048 |

| ES*RELATION | 0.316 | 1 | 0.287 |

| Panel C: Ordinal interaction contrast coding test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Planned contrast | t-statistic | p-value (one-tailed) | |

| (−3, +1, −2, +4) | 1.736 | 0.044 | |

- Note: Dependent variable, IMPAIR, is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if a participant has indicated the minimum acceptable discount rate to be 11.2% or greater, 0 otherwise. A value of 1 indicates that the participant will require the client to recognise an impairment in order to receive an unqualified audit opinion. Independent variables = ES and RELATION. Early-stage conversation (ES) is manipulated at two levels: Presence or Absence. Past auditor–client relationship (RELATION) is manipulated at two levels: Collaborative and Contentious.

Panel A of Table 5 reports the cell means of the proportion of participants that are likely to insist on an impairment across the four treatments. The proportion is higher in the contentious client treatment (51.6%) as compared with the collaborative client treatment (31.6%). The significant main effect of RELATION (χ2 = 2.790, p = 0.048), as reported in panel B of Table 5, suggests that past auditor–client relationships influence the auditors' motivated reasoning. That is, auditors appear to adopt a more compromising approach with collaborative clients by setting a higher tolerable limit, thereby being less likely to insist on an impairment. On the other hand, auditors adopt a more contending approach with difficult clients by setting a lower tolerable limit and are thereby more likely to insist on an impairment.

The effect of an early-stage conversation on auditors' decisions is also as expected. The proportion of auditors that will insist on an impairment are relatively lower in the ES condition (38.9%) compared with the non-ES condition (42.4%). However, the difference between the means of the two conditions is not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.040, p = 0.421). This suggests that having an early-stage conversation with an ME does not significantly influence the auditors' decision to insist on an impairment. Overall, the findings do not support H2.

To examine the interaction effect as predicted in H4, we conduct a planned contrast. As predicated in H4, the mean difference between auditors' decisions under the ES-Contentious condition and the non-ES-Contentious condition is found to be greater than the mean difference between the ES-Collaborative condition and non-ES-Collaborative condition. We employ the same contrast coding as used in Table 3 but reverse the signs as rejection of the ME's work is examined instead of acceptance. The results shown in panel C of Table 5 highlight a significant ordinal interactive effect between ES and RELATION on the auditors' decisions to insist on an impairment (t = 1.736, p = 0.044). We then plot the interaction between ES and RELATION on auditors' decisions to insist on an impairment in Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6, the downward slope of the line for contentious clients indicates that having an early-stage conversation weakens the contending approach auditors adopt with difficult clients. Therefore, our prediction in H4 is supported, suggesting that the presence of an early-stage conversation has a larger negative impact on auditors' decisions to require an impairment when the auditor–client relationship is contentious.

Overall, our results indicate that having an early-stage conversation with an ME adversely affects perceived client flexibility towards audit adjustments, thereby indicative of pressure on the auditor to yield a no-surprise audit. This perceived pressure is significantly greater when the client is considered contentious. However, in spite of the perceived pressure, auditors are unwilling to accept the work of the ME without any changes in the presence of inconsistent audit evidence. Neither having an early-stage conversation nor the past auditor–client relationship influences auditors' decisions. Our findings do provide some support for motivated reasoning phenomena with auditors more likely to propose an adjustment that meets a client's interests (i.e. achieves the desired conclusion) without compromising the auditor's position (i.e. within reasonable constraints).20 Although, having an early-stage conversation does not accentuate auditors' motivated reasoning behaviour, the unintended negative impact of early-stage conversation appears to be more pronounced under contentious auditor–client relationship conditions.

5.3 Additional tests

We conduct three additional tests to better understand our main findings. First, to further analyse auditors' perceptions of the impact of an early-stage conversation, participants answered three reflective questions at the end of the experiment. These questions serve to understand auditors' perceptions about the outcome of an early-stage conversation. Based on their personal experience, participants indicated the extent to which they agreed to the following questions: (1) Are MEs more approachable after an early-stage conversation? (2) Do clients expect auditors to resolve all potential issues during the early-stage conversation with MEs? and (3) Does an early-stage conversation with an ME ensure a no-surprise audit? Participants' responses were measured on an 11-point Likert scale where 0 = completely disagree, 5 = neutral and 10 = completely agree.

As reported in Table 6, an early-stage conversation opens doors for further communication with the ME. A majority of the participants (63.8%) agreed that MEs are more approachable after an early-stage conversation (mean = 6.48, median = 7). Approximately half of the participants (52.2%) further agreed that their clients expect them to resolve potential issues during an early-stage conversation (mean = 5.93, median = 6). Lastly, more than half of the participants (56.5%) agreed that an early-stage conversation, in fact, ensures a no-surprise audit (mean = 5.77, median = 6). The above outcomes observed in actual practice further confirm that an early-stage conversation can increase client expectations of a no-surprise audit and, thereby, potentially have an adverse impact on client flexibility towards audit adjustments.

| Do not agree (less than 5) | Neutral (5) | Agree (more than 5) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | Mean | Median | |

| MEs are more approachable after an early-stage conversation | 5 (7.2%) | 20 (29%) | 44 (63.8%) | 6.48 | 7.00 |

| Clients expect auditors to resolve potential issues during the early-stage conversation | 12 (17.4%) | 21 (30.4%) | 36 (52.2%) | 5.93 | 6.00 |

| An early-stage conversation with an ME ensures a no-surprise audit | 17 (24.6%) | 13 (18.8%) | 39 (56.5%) | 5.77 | 6.00 |

- This table reports the number (percentage) of participants that agreed to the three reflective questions. It also provides the mean and median for each question. Participants were asked to what extent they agreed to the three statements pertaining to early-stage conversations. Participant responses were measured on an 11-point Likert scale where 0 = completely disagree, 5 = neutral and 10 = completely agree.

- Abbreviation: MEs, management's experts.

Secondly, prior research indicates that perceived source credibility can influence auditors' decisions (Bernardi, 1994; Caster & Pincus, 1996; Danos & Imhoff, 1982; Goodwin, 1999; Griffith, 2015; Margheim, 1986; Rebele, Heintz, & Briden, 1988). To examine the possible influence of the perceived ME's credibility on auditors' decisions to use the ME's work, the participants were asked to indicate their confidence in the capability of the client's expert to undertake the task on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = not at all confident and 10 = very confident). Other than the early-stage conversation, the case material controlled for other credibility indicators such as the ME's experience, reputation, qualifications and objectivity. The mean assessment of the ME's capabilities is not significantly different across the treatments. We conduct ANCOVAs by incorporating the perceived ME's credibility as a control variable, and our main results still hold. The perceived ME's credibility is not significantly associated with either of the dependent variables, suggesting that it is not a concern in our experimental design.

Lastly, Griffin (2014) found that auditors view supplemental disclosures by clients regarding imprecision in fair value estimation as a substitute for adjustment and hence show a lower propensity to propose an audit adjustment. Therefore, as an additional dependent variable (ACCEPT-DISC), participants were asked to indicate the extent to which more disclosure of sensitivity analysis by the client would affect the likelihood of them accepting the work of the ME without any changes. Participants' responses were recorded on an 11-point Likert scale where 0 = significantly decrease, 5 = no change and 10 = significantly increase. The results from the main tests still hold. We conduct a two-way ANCOVA by using ACCEPT-DISC as a dependent variable, ES and RELATION as independent variables and participants total audit experience (EXP) as a covariate. We find that although additional disclosures increase the likelihood of auditors' accepting the work of MEs across all treatments, the likelihood of acceptance is significantly higher under collaborative client conditions. The findings once again indicate a reciprocity approach where auditors appear to be more considerate with collaborative clients and take a more rigid stand with contentious clients.

6 CONCLUSION

By using an experimental research method, this study examines the impact of an early-stage conversation with an ME on perceived client pressure and consequently on auditors' acquiescence to client's interests. As prior research indicates that auditors' judgement and decision-making may differ based on the auditor–client relationship, this study examines the unintended negative impact of an early-stage conversation within the context of collaborative and contentious auditor–client relationships. We argue that early-stage conversations recommended by GS 005 adversely affect perceived clients' flexibility toward proposed audit adjustments to the work of MEs. Failure of an auditor to identify and resolve all potential issues with the ME during the early-stage conversation exerts pressure on the auditor to yield to a client's expectation of a no-surprise audit and consequently make goal-consistent judgements, particularly when the auditor–client relationship is contentious.

Our study finds evidence that early-stage conversation adversely affects perceived client flexibility towards audit adjustments and that the adverse impact is significantly greater under contentious client conditions. However, our findings indicate that in spite of the low perceived client flexibility to audit adjustments, due to the early-stage conversation, auditors are unlikely to accept the work of the ME without any changes in the presence of inconsistent audit evidence. Nearly 60% of the participants indicated motivated reasoning behaviour by showing a willingness to propose an adjustment that would meet the auditors' reasonableness criteria without compromising their clients' interests, even when such an adjustment might result in auditors' accepting a more aggressive outcome. The extent of auditors' acquiescence to client's interests is found to be significantly greater under collaborative client conditions, suggesting that auditors' motivated reasoning behaviour is driven by reciprocity where auditors take a contending approach with difficult clients (demonstrate lower acquiescence) and a more compromising approach (demonstrate greater acquiescence) with collaborative clients.

Our results also indicate that an early-stage conversation can weaken the contending approach auditors intend to take with difficult clients. That is, an early-stage conversation may not influence auditors' acquiescence to client's interests, but it may soften an auditor's approach towards contentious clients. This finding suggests that an early-stage conversation may have the potential to adversely affect audit quality, particularly under contentious auditor–client relationships. In addition, the adverse impact of early-stage conversation on perceived client flexibility may result in difficult auditor–client interactions or an impasse in auditor–client negotiations. Negotiation literature emphasises the importance of assessing the client's position and anticipating arguments while planning for a negotiation (Trotman, Wright, & Wright, 2009). Hence, a decrease in perceived client flexibility toward any proposed audit adjustment to the ME's work as a result of the early-stage conversation has the potential to influence the auditors' pre-negotiation decisions.

Because this is experimental research using a scenario and measuring perceptions, it is important to consider the findings in the context of the following limitations associated with such methods. It is not possible to generalise the results from valuation experts to other types of management experts. To maintain internal validity, it is not possible to consider other contexts. For example, future researchers might examine the robustness of the findings to different levels of severity in the client–auditor relationship. Although we follow previous research methodology by using a CFO's behaviour as a proxy for client behaviour, the potential impact of corporate governance on auditor behaviour is difficult to operationalise to an experimental setting. Although the perceived strength of the client's governance structure is controlled and unlikely to influence the participants' judgements in this study, their judgements in the experimental conditions may not necessarily be consistent with their actual behaviour in practice.

The small sample size could contribute towards the observed insignificant effect of early-stage conversation on auditors' decisions. Even with a lower effect size, the impact of early-stage conversation could have been statistically significant had the sample size been larger (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010, pp. 453–467). However, the composition of the sample (i.e. auditors at manager level or above) ensures the quality of the responses. Our study does not examine the impact of an unsatisfactory early-stage conversation on auditors' decisions. Prior research indicates that a negative piece of evidence can produce a larger negative impact when anchors are high (Ashton & Ashton, 1988; Pei, Reed, & Koch, 1992). It is likely that an unsatisfactory early-stage conversation will have a more pronounced effect on auditors' evaluations and decisions. Lastly, the study does not take into account important credibility indicators such as the ME's mindset (i.e. conservative or optimistic) and the MEs' willingness to communicate and cooperate as perceived by an auditor during an early-stage conversation. Future research can incorporate such factors in the early-stage manipulation rather than limiting it to appropriateness of methodology and basis of valuation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the audit practitioners for their time and participation in the study. We are thankful to Stijn Masschelein, Michelle Leong, Vincent Chong, Warrick Van Zyl and Yuanji Wen for their ideas, comments and advice on the development of the experimental case materials. We are very grateful for the feedback provided by participants of the 2019 AFAANZ, ISAR and Asia Pacific Conference on International Accounting Issues. Special thanks go to Noel Harding for his invaluable suggestions to develop the manuscript.

ENDNOTES

- 1 We believe that actual over-reliance on MEs could imply three interrelated things. First, auditors have confidence in MEs to provide reliable information. Hence, they do not obtain audit evidence to the extent considered sufficient and appropriate by the regulator. Second, auditors adopt a confirmatory approach towards the evaluation of the work of MEs, thereby not adequately challenging the work of MEs. Finally, auditors accept the work of MEs even in the presence of inconsistent audit evidence. Ignoring or discounting inconsistent evidence could potentially result in auditors' accommodation of their clients' preferences by not proposing an adjustment, proposing a smaller adjustment or conceding during negotiation.

- 2 Studies by Griffith et al. (2015) and Backof et al. (2018) examine auditors' evaluation of fair value measurements where the information in relation to the fair value measurement is provided by management and not by an ME. However, as information pertaining to these measurements is often prepared by the client with the assistance of a valuation expert (i.e. an ME), these studies indirectly address audit issues, audit approach and interventions towards evaluation of the work of MEs.

- 3 The Guidance Statements, while approved and issued by the AUASB, do not establish new principles or amend existing standards and do not have legal enforceability (Foreword to AUASB Pronouncements, 2012, para 13–16). Guidance statements provide guidance on procedural matters or on entity- or industry-specific matters. They are designed to provide assistance to auditors and assurance providers in fulfilling the engagement objectives. They have no international equivalent. The AUASB reissued Guidance statement GS 005 ‘Using the work of an actuary’ in March 2015 as ‘Using the work of a management's expert’. The revised guidance statement expanded its applicability from actuaries to all management's experts. The Guidance statement was later revised in March 2020 as ‘Evaluating the appropriateness of a management's expert's work’ to improve audit quality and bring consistency in audit practice.

- 4 Paragraph 22 of the GS 005 (issued in 2015) recommends auditors communicate with the client's expert as early as practicable during the engagement to assess (substituted with ‘evaluate’ in the 2020 revision) if the expert's methodology and approach towards the task is appropriate for financial reporting purposes [GS 005 para 22 (AUASB, 2015), GS 005 para 39 (AUASB, 2020)]. As the recent changes to the GS 005 do not affect the context within which the ‘early-stage conversation’ requirements of GS 005 are evaluated in this paper, we continue to make reference to the GS 005 (para 22) issued in 2015 in this paper.

- 5 Ethics approval from the Human Ethics Office of Research Enterprise of the university was sought for this experimental research.