Investors' perceptions of nonaudit services and their type in Germany: The financial crisis as a turning point

Abstract

As a result of mistrust in the auditing profession, legislators and regulators continue to impose restrictions to the joint provision of audit and nonaudit services (NAS) to protect investors' interests. However, investors may perceive NAS differently than legislators, and it is an open question whether a ban on NAS always aligns with investors' interests. Little evidence exists on investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS in the continental European regulatory environment, including Germany. The unique features of the German legal and regulatory environment raise questions of its ability to comfort investors that auditors resist client-induced biases in financial reporting. To empirically investigate and test this, we use earnings response coefficients (ERC) to measure investors' perceptions of earnings quality and examine the associations between ERC and NAS fees. Surprisingly, we do not find significant associations between ERC and NAS fees for our entire sample period 2005–2015. For further examination, we split the sample before and after the financial crisis in 2008–2009. The findings indicate that, in the pre-financial crisis period 2005–2007, investors perceive large NAS fees negatively, and this concern also extends to the components of the NAS fees. In contrast, in the post-financial crisis period 2010–2015, investors perceive large NAS fees positively and favorable perceptions of tax services are the driver of this result. We discuss the findings in light of the regulatory initiatives in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and the recent EU supranational prohibitions of NAS and the German application of these.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research, regulators, and the auditing profession recognize that a “perception” that an auditor's independence is impaired by high levels of nonaudit services (NAS) is potentially as serious as a factual impairment (DeAngelo, 1981a; Francis & Ke, 2006). As a result of mistrust in the auditing profession, legislators and regulators continue to impose restrictions to the joint provision of audit and NAS to protect investors' interests (Deutscher Bundestag, 2016; EU, 2014; European Commission [EC], 2011). However, investors may perceive NAS differently than legislators, and it is an open question whether a ban on NAS always aligns with investors' interests.

This paper uses earnings response coefficients (ERC) to measure investors' perceptions of earnings quality and examines the associations between ERC and NAS fees. Prior research evidence in Anglo-American environments on capital market participants' perceptions of NAS is mixed but favors the conclusion that investors perceive large auditor-provided NAS negatively or are indifferent (Francis, 2006). Limited inconclusive evidence exists on investor perceptions of the components of NAS (Mishra, Raghunandan, & Rama, 2005),1 and some studies report tax services to be more positively perceived (e.g., Krishnan, Visvanathan, & Yu, 2013).

This study is one of a few to assess the economic consequences of NAS provision, including NAS components, from an investor perspective and applied to an institutional setting the previous literature has not yet dealt with. Compared with the Anglo-American setting, the unique features of the German regulatory environment seem not well suited to comfort investors' concerns for the provision of NAS. Surprisingly, for our sample period 2005–2015 we are unable to conclude that large provisions of NAS and any of its components concern investors. This leads us to examine whether the financial crisis in 2008–2009 may have affected investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS. Our results indicate that, in the pre-financial crisis period 2005–2007, investors perceive large NAS fees negatively, and this concern also extends to the components of the NAS fees. The financial crisis period 2008–2009 shows similar results except for insignificance for the tax services fee component. In contrast, in the post-financial crisis period 2010–2015, investors perceive large NAS fees positively and favorable perceptions of tax services drive this result.

Our findings for the pre-financial crisis period give support to the presumption that large NAS weakened German investors' trust in the financial statements. Thus, we have a case for stricter regulations of the provision of NAS. The findings for the years following the crisis indicate, however, that large NAS fees result in a higher perceived financial reporting quality by investors. This suggests that investors' concerns for auditor independence no longer dominate perceived benefits from auditor-provided NAS, such as reduced transaction costs and knowledge spillover benefits from NAS that improve the quality or efficiency of the audit.2

A priori, it was not clear to us how the financial crisis would affect investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS. Turmoil in the financial markets during the financial crisis in 2008–2009 initiated heavy criticism of the auditing profession (e.g., Arnold, 2009; Sikka, 2009). The crisis could, therefore, have drawn investors' attention to the potential problems with NAS provision and provoked their skepticism of earnings numbers (e.g., Kwon, Park, & Yu, 2017). Also possible, and consistent with our findings, is that investors may have recognized that the crisis could have served as a disciplining mechanism to mitigate weaknesses in earnings quality (Eilifsen & Knivsflå, 2013; Francis, Hasan, & Wu, 2013). During and in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, regulators such as the EC strongly signaled future tightening of auditor regulations, including more restrictions on the provision of NAS to audit clients (e.g., EC, 2008, 2010). We observe significantly lower NAS fees in the post-crises period compared with the pre-crisis period. Thus, the finding of a positive perception associated with tax services in the post-crises period is in the context of significantly lower fee levels. The lower NAS fees could signal to investors the avoidance of NAS with a higher risk to independence, leading to a predominance of perceived knowledge spillovers benefits over independence concerns. Thus, the financial crisis and regulatory signals may have prevented supervisory boards, audit committees, and auditors from taking unwarranted risks with respect to independence to a degree sufficiently to calm investors' independence concerns. Our analyses and results do not, however, fully unveil the underlying cause(s) of the change in investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS after the financial crisis.

In 2014 the EU approved new regulations of the auditing sector and introduced supranational prohibitions of NAS for public interest entities (PIEs), a so-called “black list” of prohibited NAS (EU, 2014).3 In addition, a cap on the provision of NAS was introduced. In the application of the new EU regulations, the German Parliament decided in 2016 to use the EU option to allow valuation and certain tax services on the “black list,” and not to use the option to deviate from the EU upper limit cap of 70% of NAS fees relative to the audit fee.4 Our findings give arguments in support of the stricter regulation of auditor-provided NAS in Germany and give support to the German decision to use the option to allow certain tax services on the EU “black list.”

Section 2 discusses specific features of the German setting that may be relevant for German investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS, and NAS regulation in Germany and the EU in our sample period. Section 3 reviews relevant research literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 4 presents the sample, tests, including a description of our methodology, and results. Section 5 gives a summary and conclusions.

2 SPECIFICS OF THE GERMAN SETTING

2.1 Litigation risk and oversight setting

German investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS may be influenced by certain specifics of the German regulatory environment, particularly auditors' litigation risk, public oversight of auditors, and the regulation of the provision of NAS, including the disclosure of auditor fees. These German specifics are presented in the following and serve, together with prior research, to motivate the hypotheses.

The literature indicates that the investor protection environment and auditors' litigation exposures affect financial reporting and audit quality (e.g., Ball, Kothari, & Robin, 2000; Ball & Shivakumar, 2008; Choi & Wong, 2007; Djankov, McLiesh, & Shleifer, 2007; Francis, Khurana, & Pereira, 2003; Francis & Wang, 2008; Gul, Zhou, & Zhu, 2013; Leuz, Nanda, & Wysocki, 2003). Investor protection is considered being weak in Germany (Djankov et al., 2007; Gul et al., 2013; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Sheifer, & Vishney, 1998; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Sheifer, & Vishney, 2000). For example, Gul et al. (2013) derive scores of investor protection based on a factor analysis on four investor protection indexes (anti-director rights index, index of disclosure requirement, index of liability standard, and index of public enforcement). They report a score of −2.071 for Germany, while the USA and the UK score 0.253 and 0.939 respectively. Only two of the 30 countries in the sample have a lower investor protection score than Germany.

Litigation exposure is viewed as perhaps the most effective mechanisms to discipline auditors. The German Commercial Code caps auditors' liabilities for negligent misconduct toward audit clients; set at €4 million for listed clients. The scope for third parties to pursue actions against auditors is very limited; the German Civil Code requires that an intentional violation is established. The intent requirement severely restricts investors from suing auditors for tort actions. Given the nature of an audit, it is extremely difficult to prove that the statutory auditor acted intentionally. In addition to the Civil Code, case law may hold auditors liable to third parties for negligent misconduct.5 Judicial decisions to compensate for auditors' negligence based on previous legal cases are, however, very rare (relating to a very restricted set of circumstances and only to other cases with similar issues or facts) and normally apply a similar liability cap as previously mentioned (Gietzmann & Quick, 1998; Schmidt & Feldmüller, 2014). Thus, the German Civil Code and case law hold auditors liable only to a very limited degree for negligent misconduct. We believe, therefore, that the low risk of auditor litigation in Germany may limit investors' comfort that auditors resist client-induced biases in financial reporting. It is possible, however, that even in a low-litigation risk environment investors' concerns may be compensated for by investors' reliance on auditors' incentives to avoid reputation losses (DeFond, Raghunandan, & Subramanyam, 2002; Hope & Langli, 2010). Other compensating mechanisms, such as effective public oversight of auditors, may also discipline auditors' behaviors and bolster investors' trust in auditor independence and the fairness of audited financial statements.

A professional body, the German Chamber of Auditors, monitors auditor compliance with their professional duties, including auditor independence and objectivity.6 The Chamber organizes a system of external quality controls, which are peer reviews, of audit practices that perform statutory audits and is responsible for disciplinary observance. The Chamber sanctions auditor misconduct, but disciplinary actions are normally not made public and the identity of the disciplined party is never disclosed. Moreover, severe sanctions, such as suspension or exclusion from the profession, are rarely applied (Wirtschaftsprüferkammer, 2014). Until recently, a public body, the AOC, supervised the activities of the Chamber, including the quality control process and disciplinary observance. Members of the AOC held only part-time positions. From 2007 the AOC became responsible for inspections of PIE audits and audit firms with PIE clients; annually for audit firms with more than 25 PIE clients and at least every third year for other firms. The Chamber's inspectors performed these inspections on the AOC's behalf.7 The modest role of the public oversight of auditors in Germany in our sample period, in addition to the lack of transparency in disciplinary cases against auditors, calls into question the effectiveness of the German system of oversight of auditors in addressing investors' concerns about auditors' incentives to control client-induced biases in financial reporting.

Although the investor protection environment, auditors' litigation exposure, and public oversight of auditors are commonly believed to be fundamental mechanisms for disciplining auditors, the potential perceived adverse effects of auditor-provided NAS may also be controlled by restricting the provision of NAS. Further, adequate disclosure of auditor fees may be crucial in the formation of investors' perceptions (DeAngelo, 1981a).

2.2 German nonaudit services regulations

The German Commercial Code regulates the provision of NAS by the statutory auditor to audit clients and requires auditor fee disclosure in the notes to the financial statements. From June 2016, additional restrictions on NAS are imposed on German PIEs as a result of the new EU regulatory decision, and these are discussed in Section 2.3. The Commercial Code reflects a mixture of principle-based and rule-based approaches, and many legal terms in the Code are open for interpretation. See Appendix 1 for prohibited specific NAS in the Code and in our sample period.8

- fees for the statutory audit;

- fees for assurance services other than the statutory audit;

- fees for tax services;

- fees for other consultancy services.

In the paper we refer to the services beyond the statutory audit as assurance NAS, tax NAS, and other NAS. The Code does not require finer specification within NAS categories, and no official guidance exists for which service to include in a category. Sometimes, however, companies voluntarily disclose in the notes the types of services within a given category.

Assurance NAS typically include voluntary audits of consolidated entities and statutory audit-related services such as review of interim financial reporting and assurance of pro-forma financial information. Inspection of fee disclosure notes to the financial statements of our sampled companies reveals that assurance NAS may occasionally include services such as due diligence, assurance related to bond issues, assurance of internal control systems, assurance of implementation of information technology (IT) systems, issue of comfort letters, and confirmation of debt covenants.

The financial statement notes also show that commonly demanded tax services include tax declaration support, review of tax assessment notes, tax planning, tax advice regarding transactions, transfer pricing issues, tax advice to German employees with temporary appointments abroad, tax due diligence, tax advice regarding a restructuring, or support with regard to tax audits.

Our category, “other NAS” includes all NAS other than assurance NAS and tax NAS. This residual category may include a variety of NAS (e.g., training and consulting with regard to IT systems, expert opinions on managerial problems, financial due diligence, merger and acquisition advice, and bond issue advice) (Sattler, 2011, p. 118; IDW, 2012, p. 776). The other NAS fee information is normally reported as the aggregate without further disclosure of its types.

Based on the foregoing discussion, we argue that the flexibility inherent in the NAS regulations, including the disclosure requirements of NAS fees, may not be very effective in comforting investors of potential negative effects of NAS on audit quality.

2.3 EU nonaudit services regulations for public interest entities and the German application

The EU 8th Directive requires that all statutory auditors and audit firms are subject to principles of professional ethics, addressing their public-interest function, their integrity and objectivity, their professional competence, and the concept of due care (EU, 2006). The directive refers to the EC's Recommendation on Statutory Auditors' Independence in the EU: A Set of Fundamental Principles (EC, 2002). The recommendation, like the international Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, adheres to the conceptual framework approach to auditor independence and serves as a benchmark of good practice.

In contrast, the new EU regulations on NAS to PIEs are rule based and ban specific NAS, known as the “black list.” Appendix 2 summarizes the “EU black” list for PIEs (EU, 2014). Germany decided to use the member state option to deviate from the “black list” and to allow the provision of certain tax services (preparation of tax forms, identification of public subsidies and tax incentives, and provision of tax advice) and the provision of valuation services whenever they are immaterial or have no direct effect on the financial statements. The EU also introduced a mandatory cap for NAS; that is, total NAS fees shall not exceed 70% of the average of the audit fees paid in the last three consecutive financial years. Germany did not use the option to deviate from the upper limit cap of 70%.

The new EU and German regulations for PIEs are more restrictive than those of the Commercial Code. The “black list” has a wider scope and prohibits additional NAS, such as payroll services, designing and implementing internal control or risk management procedures related to the preparation and/or control of financial information, and certain human resources services. Further, the “black list” also specifies the prohibited NAS in more detail, leaving less room for judgment. Finally, a fee cap for PIEs on NAS did not exist previously in Germany.

3 PRIOR RESEARCH AND HYPOTHESES

The literature on the joint provision of audit and NAS discusses opposing effects on clients' earnings quality from the provision of NAS. On the one hand, NAS increase the economic bond between the auditor and client and may expose the auditor to self-review risk in the audit; both of these threaten auditor objectivity (Arruñada, 1999; DeAngelo, 1981b; Quick & Warming-Rasmussen, 2015; Ruddock, Taylor, & Taylor, 2006; Simunic, 1984; Zhang & Emanuel, 2008). On the other hand, provision of NAS may improve the quality of financial statement audits through knowledge spillover from performing NAS (Arruñada, 1999; Knechel, Sharma, & Sharma, 2012; Simunic, 1984).

To document investors' perceptions of NAS, capital market studies typically examine the effect of NAS on the relationship between stock returns and earnings.10 For example, a negative association between the ERC and NAS fees indicates that investors perceive that purchasing additional NAS weakens the quality of earnings. Several prior studies find such a negative association (Francis & Ke, 2006; Frankel, Johnson, & Nelson, 2002; Gul, Tsui, & Dhaliwal, 2006; Krishnan, Sami, & Zhang, 2005; Lim & Tan, 2008), but other studies only find that ERC and NAS are negatively associated under restrictive conditions (Eilifsen & Knivsflå, 2013; Higgs & Skantz, 2006) or find no such association (Ashbaugh, LaFond, & Mayhew, 2003; Ghosh, Kallapur, & Moon, 2009). The mixed results indicate that investors may either be concerned or indifferent to high levels of NAS fees.

To test our hypotheses, we use earnings-response regressions based on the annual returns–earnings relation11 (Campa & Donnelly, 2016; Eilifsen & Knivsflå, 2013; Fan, Chen, & Jung, 2010; Ghosh et al., 2009; Gul et al., 2006; Holland & Lane, 2012; Lai & Krishnan, 2009).

This is the first capital market study in the German environment on the effect of NAS and its components on investors' perceptions of earnings quality. Prior surveys and experimental research indicate that the provision of NAS may impair the appearance of auditor independence (Dykxhoorn & Sinning, 1982; Meuwissen & Quick, 2009; Quick & Warming-Rasmussen, 2009, 2015). Findings from the limited research in the German environment of the potential adverse effect of NAS on the actual outcome of the audit process are mixed. Ratzinger-Sakel (2013) did not find that the level of NAS fees is related to the likelihood of issuing a going-concern report. Three other German studies (Krauss & Zülch, 2013; Lopatta, Kaspereit, Canitz, & Maas, 2015; Quick & Sattler, 2011) indicate a positive relationship between relatively high levels of NAS and abnormal accruals.

Low investor protection, including auditors' low litigation risk, and modest public oversight of auditors, may enhance investor concern about the joint provision of audit and NAS. This, together with the prior research findings, leads us to expect that investors perceive NAS negatively in Germany.

Hypothesis 1.Investor perceptions are negatively associated with the magnitude of auditor-provided NAS.

In addition to the NAS fee total, the notes to the financial statements disclose the fees of the three components: assurance NAS, tax NAS, and other NAS (residual). Occasionally, individual NAS types within a component are disclosed in the notes, but not their fees. Investors therefore base their perceptions on this incomplete disclosure of information about the specific NAS.

Typical assurance NAS, such as review of interim financial reporting, and assurance of pro-forma financial information are closely related to the audit, with potential for knowledge spillover benefits and modest exposure to the auditor self-review threat. In contrast, some other services reported as assurance NAS (e.g., due diligence and assurance of implementation of IT systems and internal control systems) may raise investors' concerns regarding auditor objectivity in the audit.

While the provision of assurance NAS can improve audit efficiency, incumbent auditors may also impair their independence as a result of offering assurance NAS to their clients. The net effect of the provision of assurance NAS on earnings quality depends on which effect dominates, and it is an open question of how strongly the weak German investor protection environment affects investors' independence concerns regarding assurance NAS. Based on the foregoing discussion, we state a nondirectional hypothesis for assurance NAS:

Hypothesis 2(a).Investor perceptions are associated with the magnitude of auditor-provided assurance NAS.

Research suggests that tax services have significant potential for providing knowledge spillover benefits and therefore enhance financial reporting quality or decrease audit effort. For example, Krishnan and Visvanathan (2011) posit that the joint provision of audit and tax services is likely to detect contentious issues that have implications for financial reporting on a timely basis, enabling the auditor to take steps immediately to constrain future earnings management attempts by the managers.

Several studies support the conjecture that provision of tax NAS enhances financial reporting quality (using proxies such as restatements, abnormal accruals, loss avoidance, meeting of analyst forecasts, and the quality of the estimated tax reserves) consistent with the knowledge spillover benefits argument (Choi, Lee, & Jun, 2009; Gleason & Mills, 2011; Kinney, Palmrose, & Scholz, 2004; Krishnan & Visvanathan, 2011; Robinson, 2008; Seetharaman, Sun, & Wang, 2011). In a capital market study, Krishnan et al. (2013) find that the value-relevance of earnings increases with the ratio of tax fees over total fees paid to the auditor.12 Huang, Mishra, & Raghunandan (2007) find only weak evidence that distorted financial statements (using abnormal accruals as proxy) are less likely when tax fee ratios are high, while Mishra et al. (2005) find a positive association between the tax fee ratio and the proportion of votes against auditor ratification, indicating that investors' concerns regarding auditor independence dominate any knowledge spillover benefits.13

While there is evidence from the Anglo-American environment that the provision of tax NAS can improve audit efficiency, it is unclear in the German environment, with its low investor protection and the closer alignment between financial and tax accounting, how strongly tax NAS raise investors' concerns of a lack of independence. Based on the foregoing discussion, we state a nondirectional hypothesis for tax NAS:

Hypothesis 2(b).Investor perceptions are associated with the magnitude of auditor-provided tax NAS.

It follows from the discussion and the previous three hypotheses that investors' concerns are expected to prevail for the residual, other NAS.

Hypothesis 2(c).Investor perceptions are negatively associated with the magnitude of auditor-provided other NAS.

The worldwide financial and economic crisis (2008–2009) was an exogenous shock and wreaked havoc in the financial markets around the world. It brought financial institutions and businesses to the brink of a collapse and required government bailouts of unpredicted proportions. Investors' confidence eroded, and their perceived risk, and thus cost of capital, increased noticeably (European Investors' Working Group, 2010). The financial crisis raised the question about the role and value of the audit by academics and regulators (e.g., Arnold, 2009; EC, 2010, 2011; EU, 2014; Geiger, Raghunandan, & Riccardi, 2014; Sikka, 2009). From the standpoint of market participants, had auditors failed to play the role of market “watchdogs” and “protectors” of earnings quality? The crisis can have forced investors to recognize the weaknesses in earnings quality that existed all along and provoke their skepticism of earnings numbers (e.g., Kwon, Park, & Yu, 2018).

Already towards the end of the crisis, return expectations, risk tolerance, and perceptions recovered (Hoffmann, Post, & Pennings, 2013). After responses were taken, investor confidence recovered buoyantly (Carmassi, Gros, & Micossi, 2009). During and in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, regulators such as the EC strongly signaled future tightening of auditor regulations, including more restrictions on the provision of NAS to audit clients (EC, 2008, 2010, 2011).14 Investors may have recognized that the crisis could serve as a disciplining mechanism to mitigate weaknesses in earnings quality (Francis et al., 2013). Such recognition may be particularly potent when legislators and regulators clearly signal that stricter regulations will be adopted (Eilifsen & Knivsflå, 2013). Potentially, investors may have assessed that auditors and relevant corporate parties, such as audit committees and the supervisory boards, took the signals seriously before any new regulation came into force, including that the parties become more alert that the provision of NAS may conflict with auditor independence.

Research Question: Did the financial crisis affect investor perceptions of auditor-provided NAS and its components?

4 SAMPLE, TESTS, AND RESULTS

4.1 Sample selection

The sample consists of companies at the Deutsche Börse CDAX index in the 11-year period 2005–2015. The CDAX index includes all stocks on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange that are listed in the General Standard or Prime Standard market segments. Stock market and accounting data were collected from Worldscope and Datastream. The audit data were hand-collected data from annual reports. As reported in Table 1, panel A, the initial number of company-year observations was 5,632. We deleted observations from financial-sector companies (927), from incomplete data sets (1,173), and for other reasons (809).15 Our final sample consists of 2,723 company-year observations for 379 individual companies for the 11-year period.

| A: Sample selection on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company-year observations | ||

| Available company-year observations 2005–2015 | 5,632 | |

| — | Financial company-year observations | 927 |

| = | Nonfinancial company-year observations | 4,705 |

| — | Missing observations | 1,173 |

| — | Excluded observations for other reasons | 809 |

| = | Selected sample | 2,723 |

| Number of companies included in the selected sample | 379 | |

| B: Definition of variables | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Definition |

| RETURN | Stock market return for company j (1, 2, …, 379) in year t (2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015). RETURN is adjusted for dividends paid and calculated from 8 months before to 4 months after the end of fiscal year t. |

| EARN | Reported net income of company j for fiscal year t divided by the market value of equity 8 months before the end of fiscal year t. |

| NAF | Ratio of nonaudit fee to total auditor fee of company j for fiscal year t. |

| NAF1 | Ratio of other assurance services (than audit) fee to total auditor fee of company j for fiscal year t. |

| NAF2 | Ratio of tax services fee to total auditor fee of company j for fiscal year t. |

| NAF3 | Ratio of other services fee (nonaudit fee minus other assurance services fee and tax services fee) to total auditor fee of company j for fiscal year t. |

| LEV | Total liabilities divided by total assets of company j for fiscal year t. |

| STDRET | Standard deviation of monthly stock returns of company j calculated using 30 months before the end of fiscal year t. |

| MBV | Market value of equity divided by book value of equity of company j at the end of fiscal year t. |

| LOSS | Indicator variable, coded as 1 if earnings are negative for company j for fiscal year t, and 0 otherwise. |

| SIZE | Natural logarithm of market value of equity of company j at the end of fiscal year t. |

| BIG4 | Indicator variable, coded as 1 if a company is audited by a Big 4 auditor, and 0 otherwise. |

| YEAR | Set of year dummies, coded as 1 for the respective year, and 0 otherwise. |

| INDUSTRY | Set of industry dummies, coded as 1 for the respective DAX sector of the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, and 0 otherwise. |

Panel B of Table 1 defines the variables involved in testing the hypotheses.

4.2 Descriptive statistics

Table 2, panel A, presents descriptive statistics for the entire investigation period (2005–2015). The average stock return (RETURN) is 14.3% and the average return on equity (EARN) is about 1.9%. The average nonaudit fee ratio (NAF) is 27.9%, ranging from 11.1% to 42.3% from the first to the third quartile. The means of the three categories of nonaudit fees ratios are quite close, with the highest average of 10.5% for other nonaudit services (NAF3). The average fee ratio for other assurance services (NAF1) and tax services (NAF2) is the same and 8.7%.16 Debt capital is on average the most important source of capital (LEV, 62.3%), and the average market-to-book ratio (MBV) is 196.4%. The percentage of companies reporting a loss (LOSS) is 24%, and 65.8% of the companies are audited by one of the four big audit firms (BIG4).

| A: Descriptive statistics for the sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | SD | First quartile | Median | Third quartile |

| RETURN | 2,723 | 0.143 | 0.571 | −0.186 | 0.057 | 0.358 |

| EARN | 2,723 | 0.019 | 0.500 | 0.002 | 0.051 | 0.089 |

| NAF | 2,723 | 0.279 | 0.202 | 0.111 | 0.258 | 0.423 |

| NAF1 | 2,723 | 0.087 | 0.131 | 0 | 0.016 | 0.133 |

| NAF2 | 2,723 | 0.087 | 0.127 | 0 | 0.019 | 0.140 |

| NAF3 | 2,723 | 0.105 | 0.137 | 0 | 0.052 | 0.167 |

| LEV | 2,723 | 0.623 | 1.990 | 0.392 | 0.558 | 0.687 |

| STDRET | 2,723 | 0.114 | 0.060 | 0.074 | 0.100 | 0.137 |

| MBV | 2,723 | 1.964 | 56.708 | 0.994 | 1.616 | 2.597 |

| LOSS | 2,723 | 0.240 | 0.427 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SIZE | 2,723 | 5.404 | 2.233 | 3.694 | 5.050 | 6.905 |

| BIG4 | 2,723 | 0.658 | 0.475 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| B: Pearson correlation matrix | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | RETURN | EARN | NAF | NAF1 | NAF2 | NAF3 | LOSS |

| EARN | 0.154*** (0.000) | ||||||

| NAF | −0.016 (0.392) | 0.033* (0.084) | |||||

| NAF1 | −0.057*** (0.003) | −0.001 (0.959) | 0.493*** (0.000) | ||||

| NAF2 | 0.026 (0.175) | −0.004 (0.836) | 0.493*** (0.000) | −0.118*** (0.000) | |||

| NAF3 | 0.006 (0.764) | 0.054*** (0.005) | 0.546*** (0.000) | −0.119*** (0.000) | −0.088*** (0.000) | ||

| LOSS | −0.181*** (0.000) | −0.385*** (0.000) | −0.016 (0.401) | 0.038** (0.045) | −0.078*** (0.000) | 0.012 (0.522) | |

| BIG4 | −0.004 (0.833) | 0.033* (0.087) | 0.099*** (0.000) | 0.109*** (0.000) | −0.016 (0.413) | 0.056*** (0.003) | −0.046** (0.017) |

- *, **, *** Indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively (two-tailed). The values in parentheses are the respective p-values. The correlation coefficients are based on the sample of 2,723 company-year observations; see Table 1, panel A. The variables are defined in Table 1, panel B.

Table 2, panel B, presents correlations between selected variables. The stock market return (RETURN) is significantly positively correlated with the level of earnings (EARN) and significantly negatively correlated with other assurance services (NAF1) and the existence of a loss (LOSS). Following from the variable definitions, EARN is significantly negatively correlated with LOSS. In addition, there is a significant positive correlation between EARN and NAF3. Significant positive correlations are observed between the NAS fee ratio (NAF) and its three component ratios (NAF1, NAF2, and NAF3). LOSS correlates significantly positively with other assurance services (NAF1) and significantly negatively with EARN and tax services (NAF2). This may reflect decreased focus on tax issues and the greater demand for other assurance services for loss-making companies. Finally, there are significant positive relations between BIG4 audits and NAF, NAF1, and NAF3.

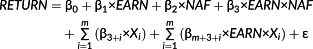

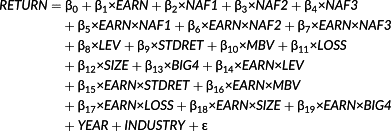

4.3 Test of hypotheses and research question

To test the hypotheses, we use the ERC from earnings-response regression models as a proxy for investor perceptions of earnings quality (Eilifsen & Knivsflå, 2013; Francis & Ke, 2006; Frankel et al., 2002; Ghosh et al., 2009; Gul et al., 2006; Krishnan et al., 2005, 2013; Lim & Tan, 2008).

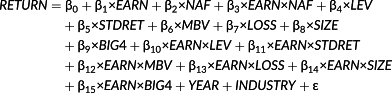

(1)

(1) (2)

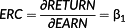

(2) (3)

(3)Our primary interest when testing hypothesis is the interaction between EARN and NAF, β3 (i.e., the effect of NAF on ERC, cf. Equation 2).17

(4)

(4)Following previous research, we include in the main tests the following control variables (Xi): LEV and STDRET to control for firm risk (Collins & Kothari, 1989), MBV as a proxy for growth prospects (Lipe, Bryant, & Widener, 1998), LOSS as a control variable for earnings persistence (Hayn, 1995), and SIZE to control for size effects (see Francis & Ke, 2006). Since large audit firms may moderate investors' concerns of independence from providing NAS (Eilifsen & Knivsflå, 2013; Francis, 2004; Gul et al., 2006), we include BIG4. Year dummies (YEAR) are used to control for time series variations. Finally, to capture potential industry-specific factors that are not completely covered by the other firm-specific controls, industry dummies (INDUSTRY) are included in the regressions.18

(6)

(6)Table 3 reports the regression results for Equations 5 and 6 in two separate main columns. As expected, reported income (EARN) is positively and significantly associated with stock market return (RETURN). The coefficient of our test variable for hypothesis (EARN × NAF) is negative but not significant. Hypothesis is not supported. Contrary to our expectation, we cannot conclude that investor perceptions are negatively associated with the magnitude of auditor-provided NAS for our entire sample period.

| Variable | Impact of NAF on ERC | Impact of components of NAF on ERC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | t | Coeff. | t | |

| Intercept | −0.416*** | −8.022 | −0.434*** | −8.303 |

| EARN | 0.238** | 2.488 | 0.281*** | 2.799 |

| NAF | −0.105** | −2.167 | ||

| NAF1 | −0.261*** | −3.365 | ||

| NAF2 | −0.007 | −0.092 | ||

| NAF3 | −0.072 | −1.029 | ||

| EARN × NAF | −0.025 | −0.298 | ||

| EARN × NAF1 | −0.136 | −0.657 | ||

| EARN × NAF2 | 0.229 | 1.482 | ||

| EARN × NAF3 | −0.133 | −1.153 | ||

| LEV | −0.002 | −0.339 | −0.003 | −0.627 |

| STDRET | 1.747*** | 9.271 | 1.793*** | 9.462 |

| MBV | 0.001** | 2.390 | 0.001** | 2.361 |

| LOSS | −0.241*** | −9.387 | −0.233 | −8.921 |

| SIZE | 0.030*** | 5.106 | 0.032*** | 5.513 |

| BIG4 | −0.020 | −0.915 | −0.021 | −0.974 |

| EARN × LEV | 0.001 | 0.223 | 0.000 | −0.070 |

| EARN × STDRET | 0.139 | 0.765 | 0.057 | 0.297 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.001 | 1.119 | 0.001 | 1.111 |

| EARN × LOSS | −0.144*** | −2.724 | −0.176*** | −3.129 |

| EARN × SIZE | −0.023* | −1.915 | −0.027** | −2.210 |

| EARN × BIG4 | 0.007 | 0.149 | 0.029 | 0.577 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | ||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.298 | 0.300 | ||

| F-statistics | 30.636*** | 28.108*** | ||

| N | 2,723 | 2,723 | ||

- *, **, *** Indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively.

The coefficients of our test variables for the components of NAS, EARN × NAF1, EARN × NAF2, and EARN × NAF3, are negative, positive and negative respectively, but none are significant. The components of NAS do not associate with the magnitude of auditor-provided NAS and hypotheses 2(a), 2(b), and 2(c) are not supported. Surprisingly, all our test variables turned out as insignificant and we do not find support for any of the four hypotheses for the entire sample period 2005–2015.19

Next, we turn to our research question: Did the financial crisis affect investor perceptions of auditor-provided NAS and its components? We partition our sample in the pre-financial crisis period 2005–2007, the financial crisis period 2008–2009, and the post-financial crisis period 2010–2015.

Table 4, panel A, presents the descriptive statistics for the three subsample periods, while panel B presents the correlation matrix between selected variables for each subsample period.

| A: Descriptive statistics for the subsample periods | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | SD | First quartile | Median | Third quartile |

| Pre-financial crisis period, 2005–2007 | ||||||

| RETURN | 769 | 0.168 | 0.621 | −0.181 | 0.057 | 0.379 |

| EARN | 769 | 0.038 | 0.351 | 0.008 | 0.052 | 0.085 |

| NAF | 769 | 0.315 | 0.195 | 0.150 | 0.296 | 0.446 |

| NAF1 | 769 | 0.092 | 0.142 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.138 |

| NAF2 | 769 | 0.101 | 0.131 | 0 | 0.042 | 0.162 |

| NAF3 | 769 | 0.121 | 0.147 | 0 | 0.065 | 0.194 |

| LEV | 769 | 0.532 | 0.234 | 0.369 | 0.562 | 0.679 |

| STDRET | 769 | 0.115 | 0.062 | 0.075 | 0.099 | 0.137 |

| MBV | 769 | 2.902 | 16.125 | 1.111 | 1.786 | 2.895 |

| LOSS | 769 | 0.220 | 0.414 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SIZE | 769 | 5.117 | 2.112 | 3.505 | 4.771 | 6.500 |

| BIG4 | 769 | 0.609 | 0.488 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Financial crisis period, 2008–2009 | ||||||

| RETURN | 504 | 0.109 | 0.755 | −0.395 | −0.059 | 0.459 |

| EARN | 504 | −0.054 | 0.578 | −0.066 | 0.048 | 0.095 |

| NAF | 504 | 0.278 | 0.192 | 0.117 | 0.257 | 0.412 |

| NAF1 | 504 | 0.090 | 0.132 | 0 | 0.021 | 0.139 |

| NAF2 | 504 | 0.089 | 0.127 | 0 | 0.025 | 0.146 |

| NAF3 | 504 | 0.099 | 0.131 | 0 | 0.042 | 0.170 |

| LEV | 504 | 0.554 | 0.278 | 0.374 | 0.564 | 0.686 |

| STDRET | 504 | 0.139 | 0.058 | 0.102 | 0.132 | 0.166 |

| MBV | 504 | 1.605 | 2.553 | 0.735 | 1.204 | 1.971 |

| LOSS | 504 | 0.321 | 0.468 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SIZE | 504 | 5.022 | 2.214 | 3.381 | 4.717 | 6.341 |

| BIG4 | 504 | 0.653 | 0.477 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Post-financial crisis period, 2010–2015 | ||||||

| RETURN | 1,450 | 0.142 | 0.459 | −0.120 | 0.077 | 0.322 |

| EARN | 1,450 | 0.035 | 0.535 | 0.007 | 0.051 | 0.090 |

| NAF | 1,450 | 0.261 | 0.206 | 0.079 | 0.240 | 0.409 |

| NAF1 | 1,450 | 0.082 | 0.124 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.130 |

| NAF2 | 1,450 | 0.080 | 0.124 | 0 | 0.003 | 0.122 |

| NAF3 | 1,450 | 0.099 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.047 | 0.153 |

| LEV | 1,450 | 0.695 | 2.715 | 0.406 | 0.552 | 0.691 |

| STDRET | 1,450 | 0.105 | 0.0564 | 0.069 | 0.092 | 0.123 |

| MBV | 1,450 | 1.591 | 76.813 | 1.053 | 1.717 | 2.670 |

| LOSS | 1,450 | 0.223 | 0.416 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SIZE | 1,450 | 5.689 | 2.265 | 3.977 | 5.304 | 7.252 |

| BIG4 | 1,450 | 0.686 | 0.465 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| B: Pearson correlation matrix for the subsample periods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | RETURN | EARN | NAF | NAF1 | NAF2 | NAF3 | LOSS |

| Pre-financial crisis period, 2005–2007 | |||||||

| EARN | 0.152*** (0.000) | ||||||

| NAF | −0.045 (0.213) | 0.056 (0.119) | |||||

| NAF1 | −0.099*** (0.006) | −0.046 (0.207) | 0.461*** (0.000) | ||||

| NAF2 | 0.013 (0.716) | 0.025 (0.494) | 0.432*** (0.000) | −0.166*** (0.000) | |||

| NAF3 | 0.024 (0.498) | 0.097*** (0.007) | 0.497*** (0.000) | −0.206*** (0.000) | −0.157*** (0.000) | ||

| LOSS | −0.209*** (0.000) | −0.396*** (0.000) | 0.053 (0.140) | 0.075** (0.038) | −0.092*** (0.010) | 0.081** (0.025) | |

| BIG4 | −0.008 (0.823) | 0.038 (0.297) | 0.016 (0.651) | 0.073** (0.042) | −0.067* (0.062) | 0.011 (0.760) | −0.031 (0.387) |

| Financial crisis period, 2008–2009 | |||||||

| EARN | 0.154*** (0.001) | ||||||

| NAF | −0.020 (0.661) | 0.012 (0.791) | |||||

| NAF1 | −0.017 (0.705) | 0.054 (0.230) | 0.490*** (0.000) | ||||

| NAF2 | 0.014 (0.759) | −0.015 (0.743) | 0.500*** (0.000) | −0.126*** (0.005) | |||

| NAF3 | −0.025 (0.575) | −0.022 (0.614) | 0.491*** (0.000) | −0.167*** (0.000) | −0.110** (0.014) | ||

| LOSS | −0.054 (0.229) | −0.475*** (0.000) | −0.018 (0.688) | −0.026 (0.566) | −0.076* (0.090) | 0.073 (0.101) | |

| BIG4 | 0.039 (0.382) | 0.033 (0.457) | 0.074* (0.099) | 0.119*** (0.007) | −0.045 (0.316) | 0.031 (0.484) | 0.047 (0.294) |

| Post-financial crisis period, 2010–2015 | |||||||

| EARN | 0.167*** (0.000) | ||||||

| NAF | −0.002 (0.940) | 0.033 (0.203) | |||||

| NAF1 | −0.049* (0.065) | −0.004 (0.891) | 0.515*** (0.000) | ||||

| NAF2 | 0.041 (0.116) | −0.010 (0.700) | 0.517*** (0.000) | −0.091*** (0.001) | |||

| NAF3 | 0.004 (0.889) | 0.065** (0.014) | 0.587*** (0.000) | −0.049* (0.064) | −0.048* (0.070) | ||

| LOSS | −0.244*** (0.000) | −0.345*** (0.000) | −0.049* (0.060) | 0.041 (0.117) | −0.074*** (0.005) | −0.046* (0.078) | |

| BIG4 | −0.023 (0.373) | 0.032 (0.221) | 0.168*** (0.000) | 0.134*** (0.000) | 0.035 (0.181) | 0.103*** (0.000) | −0.091*** (0.001) |

- *, **, *** Indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively (two-tailed). The values in parentheses are the respective p-values. The variables are defined in Table 1, panel B.

The average stock return (RETURN) ranges from 10.9 (crisis period) to 16.8%, with the highest mean value for the pre-crisis period and a slightly lower mean for the post-crisis period (14.2%). The average return on equity (EARN) is almost equal for pre-- and post-crisis period (3.8% and 3.5% respectively), but turns negative for the crisis period (−5.4%). The average nonaudit fee ratio (NAF) decreases for each period, from 31.5% for the pre-crisis period, to 27.8% for the crisis period, and to 26.1% for the post-crisis period. A similar pattern is observed for the three categories of nonaudit fees, (NAF1, 9.2, 9.0, 8.2%; NAF2, 10.1, 8.9, 8.0%; and NAF3, 12.1, 9.9, 9.9%). Total liabilities to total asset ratio (LEV) ranges from 53.2 (pre-crisis period) to 69.5% (post-crisis period). The pre-crisis period shows the highest mean value for the market-to-book ratio (MBV) (290.2%) and with the lowest for post-crisis period (159.1%). For the crisis period, the percentage of companies reporting a loss (LOSS) is 32.1%, while this is around 22% for the pre- and post-crisis periods. The Big 4 firms become more dominant for each period (60.9, 65.3, and 68.6%).

Table 4 presents the Pearson correlation matrix for the dependent and selected independent variables regarding the subsamples. The stock market return (RETURN) is significantly positively correlated with EARN for all three periods, and for the pre- and post-crisis periods negatively correlated with NAF1 (marginally significant for the post-crisis period) and LOSS. Following from the variable definitions, EARN is negatively correlated with LOSS throughout all three periods. Moreover, for the years before and after the crisis, a positive correlation is observed between EARN and NAF3. For all periods, NAF is significantly positively associated with NAF1, NAF2, and NAF3. For the pre-crisis period, LOSS correlates significantly positively with NAF1 and NAF3, and significantly negatively with NAF2. For the crisis period, LOSS correlates weakly negatively with NAF2. For the post-crisis period, LOSS correlates negatively with NAF (weakly significant), NAF2 and NAF3 (weakly significant). Finally, BIG4 is positively associated with NAF (weakly significant) for the crisis period and post-crisis period, NAF1 for all three periods, and NAF3 for the post-crisis period, and is negatively correlated with NAF2 (weakly significant) for the pre-crisis period.

Table 5, panel A, reports the regression results for Equation 5, where our test variable is EARN × NAF for each sub-period; the pre-crisis period 2005–2007, the crisis period 2008–2009, and the post-crisis period 2010–2015.

| Variable | Pre-crisis (2005–2007) | Crisis (2008–2009) | Post-crisis (2010–2015) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | t | Coeff. | t | Coeff. | t | |

| A: Impact of NAF on ERC | ||||||

| Intercept | −0.532*** | −5.047 | −1.011*** | −8.954 | 0.037 | 0.654 |

| EARN | 1.092** | 2.492 | 0.606** | 2.241 | 0.483*** | 3.622 |

| NAF | −0.171* | −1.755 | 0.048 | 0.404 | −0.071 | −1.240 |

| EARN × NAF | −1.179*** | −2.973 | −0.450** | −2.007 | 0.259** | 2.425 |

| LEV | 0.002 | 0.021 | −0.043 | −0.399 | −0.003 | −0.689 |

| STDRET | 1.750*** | 4.925 | 2.631*** | 5.990 | 1.361*** | 5.524 |

| MBV | 0.006*** | 2.842 | 0.038*** | 2.713 | 0.00009 | 0.380 |

| LOSS | −0.120** | −1.998 | −0.159*** | −2.609 | −0.264*** | −8.283 |

| SIZE | 0.056*** | 4.475 | 0.016 | 1.103 | 0.015** | 2.174 |

| BIG4 | −0.036 | −0.821 | 0.027 | 0.523 | −0.021 | −0.830 |

| EARN × LEV | −0.365 | −1.559 | −0.030 | −0.421 | −0.001 | −0.573 |

| EARN × STDRET | −1.266 | −1.240 | 4.513*** | 7.070 | −0.346 | −1.590 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.026* | 1.725 | −0.057** | −2.303 | 0.000 | −0.573 |

| EARN × LOSS | −0.098 | −0.467 | −1.030*** | −6.874 | −0.120* | −1.845 |

| EARN × SIZE | 0.028 | 0.454 | −0.048 | −1.409 | −0.051*** | −3.061 |

| EARN × BIG4 | 0.071 | 0.381 | −0.157 | −1.457 | −0.146** | −2.238 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.335 | 0.589 | 0.195 | |||

| F-statistics | 13.506*** | 25.033*** | 11.351*** | |||

| N | 769 | 504 | 1,450 | |||

| B: Impact of components of NAF on ERC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.569*** | −5.370 | −1.026*** | −8.995 | 0.117* | 1.870 |

| EARN | 1.123** | 2.370 | 0.652** | 2.421 | 0.512*** | 3.787 |

| NAF1 | −0.443*** | −3.129 | −0.005 | −0.030 | −0.174* | −1.720 |

| NAF2 | −0.036 | −0.236 | 0.284 | 1.589 | −0.034 | −0.378 |

| NAF3 | −0.004 | −0.026 | −0.159 | −0.873 | −0.038 | −0.442 |

| EARN × NAF1 | −1.218** | −2.195 | −1.050** | −2.198 | 0.024 | 0.093 |

| EARN × NAF2 | −2.501*** | −2.923 | 0.112 | 0.342 | 0.486*** | 2.688 |

| EARN × NAF3 | −1.230*** | −2.621 | −0.670** | −2.517 | 0.181 | 1.026 |

| LEV | −0.008 | −0.087 | −0.035 | −0.326 | −0.005 | −0.916 |

| STDRET | 1.883*** | 5.266 | 2.702*** | 6.048 | 1.385*** | 5.609 |

| MBV | 0.005*** | 2.500 | 0.036*** | 2.582 | 0.00008 | 0.352 |

| LOSS | −0.114* | −1.908 | −0.141** | −2.267 | −0.258*** | −7.991 |

| SIZE | 0.060*** | 4.756 | 0.016 | 1.085 | 0.017** | 2.457 |

| BIG4 | −0.037 | −0.849 | 0.027 | 0.537 | −0.024 | −0.933 |

| EARN × LEV | −0.333 | −1.420 | −0.018 | −0.251 | −0.002 | −0.860 |

| EARN × STDRET | −0.880 | −0.759 | 4.433*** | 6.933 | −0.410* | −1.830 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.032** | 2.101 | −0.059** | −2.301 | 0.000 | −0.589 |

| EARN × LOSS | −0.189 | −0.812 | −1.099*** | −7.062 | −0.141** | −2.061 |

| EARN × SIZE | 0.065 | 0.932 | −0.051 | −1.438 | −0.051*** | −3.065 |

| EARN × BIG4 | −0.085 | −0.408 | −0.070 | −0.586 | −0.137** | −2.086 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.341 | 0.594 | 0.196 | |||

| F-statistics | 12.362*** | 22.612*** | 10.273*** | |||

| N | 769 | 504 | 1,450 | |||

- *, **, *** Indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively.

As expected, reported income (EARN) is positively and significantly associated with stock market return (RETURN) for all three periods. Before and during the crisis, the coefficient of our test variable EARN × NAF is negative (−1.179 and −0.450 respectively) and significant (p = 0.003 and 0.045 respectively); that is, a large NAS negatively associates with ERC. This is line with the prediction of hypothesis . The result indicates that investors perceive large NAS adversely. Investors' concerns for auditor independence seem to dominate any perceived knowledge spillover benefits to the audit from NAS. For the period following the crisis, however, the coefficient of EARN × NAF is significantly positive (0.259 with p = 0.015).20 This suggests positive perceptions of NAS by investors. The finding may reflect that the crisis and the reform process starting immediately in the aftermath of the crisis changed supervisory boards', audit committees', and auditors' awareness of potential negative effects on audit quality of auditor-provided NAS. In turn, this may have eased investors' concerns from auditor-provided NAS to the extent that their perceived knowledge spillover benefits now dominate their independence concerns.

Table 5, panel B, reports the regression results for Equation 6, where our test variables are EARN × NAF1, EARN × NAF2, and EARN × NAF3, for each sub-period. Before the crisis, the coefficients of our test variables EARN × NAF1, EARN × NAF2, and EARN × NAF3 are all negative (−1.218, −2.501, and −1.230 respectively) and clearly significant (p = 0.029, 0.004, and 0.009 respectively).21 The results show that investors perceive each individual audit fee category negatively in the pre-crisis period. For the crisis period 2008–2009, the coefficients of our test variables EARN × NAF1 and EARN × NAF3 are again significantly negative (−1.050 with p = 0.028 and −0.670 with p = 0.012 respectively). We do not observe a significant association for the variable EARN × NAF2 in the crisis period.22 For the post-crisis period, only the coefficient of the test variable EARN × NAF2 is significant (p = 0.007). The coefficient has a positive sign (0.486); that is, the provision of tax NAS increases investors' confidence in reported earnings.23

To summarize, the results for the sub-periods indicate that investors before and during the crisis perceive that large NAS weaken earnings quality. Investors' concerns of biased financial reporting dominate possible knowledge spillover benefits from providing large NAS. Also, the results for the years 2005–2009 indicate that this is the case for the three NAS components individually. In contrast, the findings for the post-crisis period suggest that investors' perceived improved earnings quality with larger NAS fees. This is consistent with perceived knowledge spillover benefits from NAS dominating investors' independence concerns. Tax NAS are the driver of this finding. The results show that after the financial crisis investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS substantially changed. The positive perceptions of NAS after the crisis may be associated with the lower NAS fees in this period.24 Investors may interpret this reduction in such a way that it indicates that boards are less willing to take unwarranted independence risks.

4.4 Robustness and additional tests

We perform robustness tests for the sub-periods by changing the specification of our empirical model (additional control variables) and using alternative nonaudit fee definitions. In addition, we simulate the effect of the new German (EU) cap on NAS fees for our first two subsamples to evaluate its effectiveness if applied in the subsample periods.

The first robustness test includes two additional control variables proposed in the literature: AUDITOR CHANGE (indicator variable that equals 1 if company j changed audit firms for the fiscal year t, and 0 otherwise) and INDUSTRY LEADER (indicator variable that equals 1 if the auditor of company j had the highest audit fees in the related industry for the fiscal year t, and 0 otherwise). Table 6 reports the results.

| Variable | Pre-crisis (2005–2007) | Crisis (2008–2009) | Post-crisis (2010–2015) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | t | Coeff. | t | Coeff. | t | |

| A: Impact of NAF on ERC | ||||||

| Intercept | −0.532*** | −4.987 | −0.991*** | −8.666 | 0.138** | 2.237 |

| EARN | 1.170*** | 2.618 | 0.741** | 2.480 | 0.535*** | 3.865 |

| NAF | −0.165* | −1.672 | 0.053 | 0.437 | −0.073 | −1.262 |

| EARN × NAF | −1.139*** | −2.845 | −0.385 | −1.616 | 0.263** | 2.474 |

| LEV | 0.009 | 0.101 | −0.064 | −0.593 | −0.004 | −0.710 |

| STDRET | 1.758*** | 4.926 | 2.638*** | 5.986 | 1.320*** | 5.361 |

| MBV | 0.006*** | 2.821 | 0.045*** | 3.172 | 0.0001 | 0.440 |

| LOSS | −0.108* | −1.772 | −0.164*** | −2.699 | −0.238*** | −7.282 |

| SIZE | 0.055*** | 4.312 | 0.011 | 0.773 | 0.012* | 1.807 |

| BIG4 | −0.041 | −0.868 | 0.012 | 0.225 | −0.028 | −1.029 |

| AUDITOR CHANGE | −0.025 | −0.366 | −0.031 | −0.350 | −0.064 | −1.473 |

| INDUSTRY LEADER | 0.009 | 0.185 | 0.054 | 0.927 | 0.010 | 0.351 |

| EARN × LEV | −0.364 | −1.549 | −0.035 | −0.478 | −0.002 | −0.636 |

| EARN × STDRET | −1.409 | −1.364 | 4.374*** | 6.779 | −0.431* | −1.925 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.026* | 1.714 | −0.038 | −1.430 | 0.000 | −0.520 |

| EARN × LOSS | −0.113 | −0.540 | −1.138*** | −7.288 | −0.133* | −1.955 |

| EARN × SIZE | 0.009 | 0.132 | −0.056 | −1.573 | −0.054*** | −3.194 |

| EARN × BIG4 | 0.033 | 0.175 | −0.296** | −2.457 | −0.166** | −2.516 |

| EARN × AUDITOR CHANGE | 0.085 | 0.272 | −0.191 | −1.148 | −0.017 | −0.291 |

| EARN × INDUSTRY LEADER | 0.307 | 0.910 | 0.295** | 2.273 | 0.476*** | 3.004 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.333 | 0.592 | 0.200 | |||

| F-statistics | 11.956*** | 22.433*** | 10.541*** | |||

| N | 769 | 504 | 1,450 | |||

| B: Impact of components of NAF on ERC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.573*** | −5.338 | −1.019*** | −8.833 | 0.128** | 2.047 |

| EARN | 1.248*** | 2.570 | 1.007*** | 3.254 | 0.576*** | 4.099 |

| NAF1 | −0.447*** | −3.139 | 0.019 | 0.102 | −0.167* | −1.649 |

| NAF2 | −0.020 | −0.133 | 0.256 | 1.432 | −0.047 | −0.519 |

| NAF3 | 0.007 | 0.052 | −0.182 | −0.994 | −0.033 | −0.386 |

| EARN × NAF1 | −1.119** | −1.992 | −1.102** | −2.082 | −0.069 | −0.239 |

| EARN × NAF2 | −2.494*** | −2.897 | 0.286 | 0.850 | 0.483*** | 2.672 |

| EARN × NAF3 | −1.217*** | −2.581 | −0.913*** | −2.919 | 0.241 | 1.254 |

| LEV | 0.001 | 0.009 | −0.035 | −0.322 | −0.005 | −0.952 |

| STDRET | 1.902*** | 5.296 | 2.703*** | 6.053 | 1.342*** | 5.434 |

| MBV | 0.005** | 2.449 | 0.045*** | 3.164 | 0.00009 | 0.413 |

| LOSS | −0.099 | −1.626 | −0.136** | −2.200 | −0.234*** | −7.072 |

| SIZE | 0.060*** | 4.616 | 0.011 | 0.772 | 0.015** | 2.074 |

| BIG4 | −0.042 | −0.884 | 0.016 | 0.289 | −0.030 | −1.102 |

| AUDITOR CHANGE | −0.034 | −0.497 | −0.023 | −0.263 | −0.066 | −1.533 |

| INDUSTRY LEADER | 0.006 | 0.121 | 0.046 | 0.786 | 0.010 | 0.355 |

| EARN × LEV | −0.329 | −1.396 | −0.064 | −0.863 | −0.002 | −0.961 |

| EARN × STDRET | −1.117 | −0.950 | 4.107*** | 6.322 | −0.507** | −2.213 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.032** | 2.112 | −0.038 | −1.430 | 0.000 | −0.545 |

| EARN × LOSS | −0.223 | −0.954 | −1.216*** | −7.571 | −0.156** | −2.231 |

| EARN × SIZE | 0.038 | 0.522 | −0.074** | −1.978 | −0.056*** | −3.255 |

| EARN × BIG4 | −0.133 | −0.629 | −0.191 | −1.382 | −0.155** | −2.331 |

| EARN × AUDITOR CHANGE | 0.100 | 0.318 | −0.466** | −2.397 | −0.042 | −0.598 |

| EARN × INDUSTRY LEADER | 0.392 | 1.156 | 0.159 | 1.142 | 0.467*** | 2.947 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.339 | 0.598 | 0.200 | |||

| F-statistics | 11.117*** | 20.652*** | 9.650*** | |||

| N | 769 | 504 | 1,450 | |||

- *, **, *** Indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively.

For the years preceding the crisis, the regression coefficient for the interaction EARN × NAF is negative (−1.139) and strongly significant (p = 0.005). The coefficients for the components other assurance services fees (NAF1), tax services fees (NAF2) and other services fees (NAF3) are also negative (−1.119, −2.494, and −1.217 respectively) and clearly significant (p = 0.047, 0.004, and 0.010 respectively). For the crisis period, the coefficient for the test variable EARN × NAF is again negative (−0.385), but just missed significance (p = 0.107). For other assurance services fees (NAF1) and other services fees (NAF3), the impact is again negative (−1.102 and −0.913 respectively) and clearly significant (p = 0.038 and 0.004 respectively). As in the main test, the coefficient for tax services fees (NAF2) is positive but insignificant (0.286 with p = 0.396). After the crisis, the regression coefficient for the interaction EARN × NAF is positive (0.263) and significant (p = 0.013). Tax services fees (NAF3) exert a significantly positive effect (0.483 with p = 0.008), while the results do not show a significant relationship for the two other fee components, NAF1 and NAF3 (−0.069 with p = 0.811 and 0.241 with p = 0.210 respectively). Hence, the results for the alternatively specified regressions are basically the same as those in the main tests.

The second set of robustness tests applies alternative nonaudit fees variable definitions to the ratio between nonaudit fee and total auditor fee. Table 7 reports the results for NAF scaled by the market value of equity (panel A), for unscaled NAF (panel B), and for the natural logarithm of NAF (panel C).

| Variable | Pre-crisis (2005–2007) | Crisis (2008–2009) | Post-crisis (2010–2015) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | t | Coeff. | t | Coeff. | t | |

| A: Return-earnings regressions with scaled NAF as test variable | ||||||

| Intercept | −0.528*** | −5.008 | −0.973*** | −8.655 | 0.059 | 1.042 |

| EARN | 0.743* | 1.844 | 0.482* | 1.922 | 0.497*** | 3.550 |

| NAF | −12.833** | −2.260 | −8.005 | −1.618 | −16.056*** | −3.076 |

| EARN × NAF | −12.891** | −2.123 | −4.798* | −1.899 | −9.027** | −1.965 |

| LEV | 0.031 | 0.350 | −0.020 | −0.184 | −0.002 | −0.366 |

| STDRET | 1.761*** | 4.958 | 2.703*** | 6.174 | 1.375*** | 5.599 |

| MBV | 0.005** | 2.483 | 0.036** | 2.559 | 0.00008 | 0.370 |

| LOSS | −0.117* | −1.935 | −0.145** | −2.321 | −0.252*** | −7.825 |

| SIZE | 0.044*** | 3.341 | 0.010 | 0.684 | 0.008 | 1.202 |

| BIG4 | −0.018 | −0.418 | 0.035 | 0.682 | −0.016 | −0.615 |

| EARN × LEV | −0.275 | −1.201 | −0.003 | −0.041 | −0.001 | −0.246 |

| EARN × STDRET | −1.426 | −1.356 | 4.579*** | 7.183 | −0.402* | −1.797 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.031** | 2.108 | −0.061** | −2.404 | 0.000 | −0.611 |

| EARN × LOSS | −0.040 | −0.194 | −0.986*** | −6.542 | −0.076 | −1.149 |

| EARN × SIZE | 0.016 | 0.240 | −0.049 | −1.338 | −0.043*** | −2.607 |

| EARN × BIG4 | 0.034 | 0.182 | −0.173 | −1.543 | −0.119* | −1.833 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.333 | 0.589 | 0.197 | |||

| F-statistics | 13.393*** | 24.979*** | 11.435*** | |||

| N | 769 | 504 | 1,450 | |||

| B: Return-earnings regressions with unscaled NAF as test variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.577*** | −5.419 | −0.992*** | −8.705 | 0.023 | 0.403 |

| EARN | 0.430 | 1.251 | 0.218 | 1.161 | 0.505*** | 3.660 |

| NAF | 0.030 | 1.109 | 0.002 | 0.128 | −0.008 | −1.221 |

| EARN × NAF | −0.631** | −2.512 | −0.110 | −1.001 | 0.037 | 1.278 |

| LEV | 0.009 | 0.103 | −0.042 | −0.385 | −0.001 | −0.275 |

| STDRET | 1.742*** | 4.900 | 2.677*** | 6.096 | 1.327*** | 5.382 |

| MBV | 0.005*** | 2.756 | 0.040*** | 2.907 | 0.00009 | 0.376 |

| LOSS | −0.123** | −2.037 | −0.181*** | −3.003 | −0.261*** | −8.126 |

| SIZE | 0.054*** | 4.055 | 0.015 | 1.027 | 0.015** | 2.083 |

| BIG4 | −0.029 | −0.673 | 0.027 | 0.531 | −0.024 | −0.916 |

| EARN × LEV | −0.252 | −1.100 | 0.049 | 0.829 | −0.001 | −0.212 |

| EARN × STDRET | −1.405 | −1.327 | 4.783*** | 7.627 | −0.400* | −1.813 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.027* | 1.817 | −0.052** | −2.125 | 0.000 | −0.629 |

| EARN × LOSS | 0.073 | 0.377 | −1.007*** | −6.715 | −0.107 | −1.639 |

| EARN × SIZE | 0.101* | 1.687 | −0.024 | −0.719 | −0.047*** | −2.741 |

| EARN × BIG4 | 0.007 | 0.040 | −0.108 | −1.027 | −0.126* | −1.942 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.331 | 0.586 | 0.193 | |||

| F-statistics | 13.244*** | 24.747*** | 11.167*** | |||

| N | 769 | 504 | 1,450 | |||

| C: Return-earnings regressions with natural logarithm of NAF as test variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.399** | −2.563 | −1.024*** | −8.188 | 0.039 | 0.678 |

| EARN | 4.143*** | 4.579 | 0.223 | 0.738 | 0.453*** | 3.266 |

| NAF | −0.027* | −1.805 | 0.006 | 0.715 | −0.001 | −0.241 |

| EARN × NAF | −0.321*** | −4.680 | −0.001 | −0.042 | 0.002 | 0.260 |

| LEV | 0.046 | 0.515 | −0.052 | −0.479 | −0.002 | −0.308 |

| STDRET | 1.689*** | 4.813 | 2.661*** | 6.057 | 1.339*** | 5.431 |

| MBV | 0.006*** | 3.095 | 0.042*** | 2.985 | 0.00009 | 0.389 |

| LOSS | −0.082 | −1.362 | −0.177*** | −2.871 | −0.266*** | −8.336 |

| SIZE | 0.071*** | 4.890 | 0.009 | 0.597 | 0.013* | 1.788 |

| BIG4 | −0.039 | −0.897 | 0.025 | 0.490 | −0.023 | −0.902 |

| EARN × LEV | −0.211 | −0.936 | 0.041 | 0.431 | −0.001 | −0.218 |

| EARN × STDRET | −1.774* | 1.735 | 4.798*** | 7.633 | −0.342 | −1.457 |

| EARN × MBV | 0.019 | 1.267 | −0.049* | 1.935 | 0.000 | −0.576 |

| EARN × LOSS | −0.342 | −1.601 | −1.000*** | −6.438 | −0.097 | −1.480 |

| EARN × SIZE | 0.124** | 2.080 | −0.029 | −0.873 | −0.040** | −2.418 |

| EARN × BIG4 | 0.099 | 0.549 | −0.106 | −0.995 | −0.123* | −1.894 |

| YEAR | Included | Included | Included | |||

| INDUSTRY | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.348 | 0.586 | 0.191 | |||

| F-statistics | 14.244*** | 24.699*** | 11.082*** | |||

| N | 769 | 504 | 1,450 | |||

- *, **, *** Indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively.

Again, EARN × NAF is significantly negative in the pre-crisis period for the three alternative nonaudit fees variable definitions. The negative sign of the interaction coefficients extent into the crisis period but the coefficients are insignificant or weakly significant (for scaled NAF, panel A). In the post-crisis period EARN × NAF is positive but insignificant (for unscaled NAF and natural logarithm of NAF) or significant negative (for scaled NAF). The latter contrasts the findings in the main test. Additional results for alternative definitions of nonaudit fees for NAS categories (not tabulated) show associations quite similar to the main tests but in some cases with less significance, mainly related to tax services fees. The results from the robustness tests of alternative audit fees variable definitions confirm the previous results from the basic models except that in the post-crisis period the results become less clear.

To simulate the effect of the new German (EU) 70% cap of NAS fees relative to the audit fee for our two subsamples before and during the crisis, we exclude all company-year observations when NAF is above 0.4112.25 For the pre-crisis period, this reduces the sample from 769 to 518 company-year observations. The coefficient for the test variable EARN × NAF is still negative (−2.940) and strongly significant (p = 0.002). Additional calculations indicate that the test variable becomes insignificant when NAF does not exceed 0.36, which implies a cap of about 56% (NAF = − 0.560 with p = 0.684). Thus, for this subsample, the “optimal” cap may be lower than the 70%. For the crisis period, the sample is reduced from 504 to 377 company-year observations. The coefficient for the test variable EARN × NAF is again negative (−0.126) but not significant (p = 0.770). Thus, for the crisis period, the results do not indicate that the cap is too moderate.

5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

This study is motivated by the recent EU and German regulatory decisions to prohibit auditor-provided NAS to protect investors' interests, prior inconclusive evidence on capital market participants' perceptions of NAS and its components, and the lack of studies of investors' perceptions of NAS in the continental European regulatory environment.

Contrary to our expectation, we do not find significant associations between investors' perceptions and NAS fees for the sample period 2005–2015. This leads us to examine whether the financial crisis in 2008–2009 may have affected investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS. Our findings indicate that, in the pre-crisis period 2005–2007, investors perceive large NAS fees negatively, and this concern also extends to the components of the NAS fees. The crisis period 2008–2009 shows similar results except for insignificance for the tax services fee component. In contrast, in the post-crisis period 2010–2015, investors perceive large NAS fees positively and favorable perceptions of tax services are the driver of this result. We therefore conclude that, after the financial crisis, investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS changed significantly.

Our analyses and results do not unveil the underlying causes of the change in investors' perceptions of auditor-provided NAS after the financial crisis. A possible explanation consistent with our findings is that investors in the post-crisis period recognized that the crisis would serve as a disciplining mechanism to mitigate weakness in earnings quality. Such recognition may be particularly potent when regulators clearly signal that stricter regulations of the provision of NAS will be adopted. Thus, the financial crisis and regulatory signals may have prevented supervisory boards, audit committees, and auditors from taking unwarranted risks with respect to independence to a degree sufficiently to calm investors' independence concerns. Such explanation is supported by the drop in the NAS fees in the post-financial crisis period compared with the pre-crisis period; that is, the finding of a positive perception associated with tax services in the post-crises period is in the context of significantly lower fee levels.

The findings for the pre-crisis period and into the crisis period give reason to question the ability of the then prevailing German legal and regulatory environment to comfort investor perceptions that auditors sufficiently resist client-induced biases in financial reporting. Thus, there are arguments in support of a stricter regulation of auditor-provided NAS. Such regulation materialized in Germany in 2016 when the EU regulation and German legislators' application of the EU supranational prohibitions of NAS came into force. Immediately after the financial crisis, however, the EC announced strong intentions to reform the audit sector and to impose a radical ban on the provision of NAS. This may have significantly altered investors' perceptions of auditors' effort to protect earnings, long before new regulations came into place.

Our finding of changing investor perceptions of NAS over time points to a possible implication for research in this field. If a changed regulatory and economic context is associated with different behaviors, then we should be cautious about the “authority” of findings from the past which tend to be taken as well-established truths. Rather, this study indicates that the research around audit markets is context dependent.

The study is subject to limitations. The sample is based on German data for the period 2005–2015, an environment with some distinctive and with changing regulatory features. Examinations on how NAS affect earnings quality in other, currently not studied, regulatory environments (e.g., the more recent EU member states in eastern Europe), as well as use of an international sample to exploit variations across countries (e.g., whether a common EU cap on NAS might not be optimal or meaningful for all EU national auditing markets26), would be interesting. Although the German decision to use the option to allow certain tax services on the EU “black list” finds support in our findings (tax services fees positively associates with ERC in the post-crisis period), it is currently unclear how well the German application of the EU supranational prohibitions of NAS matches with investors' interests. Thus, an extension of our study for the years to come would be interesting for future research. Furthermore, we cannot exclude that the reporting entities changed their approach to classifying and reporting audit and NAS fees over time, which in turn may have an impact on investors' perceptions. Finally, this study focuses on equity investors' perceptions, investors as one group, and listed companies. Future research could use alternative market perception measures, such as cost of capital, and explore how other financial statements users, such as creditors (Dykxhoorn & Sinning, 1982), including financial institutions, perceive auditor-provided NAS for PIEs and non-PIEs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, Joe Carcello, Jürgen Ernstberger, Al Ghosh, David Hay, Kjell Henry Knivsflå, Lasse Niemi, Stuart Turley; and the participants at the 2014 Nordic Accounting Conference, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark; the 2015 8th EARNet Symposium, University of Lausanne, Switzerland; the 2015 77th Annual Meeting of the German Academic Association for Business Research, Vienna University of Economics and Business, Austria; and the 2017 9th EARNet Symposium, KU Leuven, Belgium, for comments on previous versions of this article.

ENDNOTES

- 1 Based on their findings, Mishra et al. (2005) argue that it will be useful to replicate some prior studies (that use a single measure of nonaudit fees) using the newer, more finely partitioned fee data.

- 2 Research has primarily focused on knowledge spillover benefits to the audit. A study by Ciconte, Knechel, and Mayberry (2014) indicates that benefits may also flow to the client purchasing NAS services.

- 3 See Appendix 2 for the EU “black list.”

- 4 The EU regulation for PIEs binds member states and is therefore directly applicable without the need for any national implementing legislation. There are, however, a number of options available in the EU regulation where member states have a choice, including opting to allow valuation and certain tax services on the “black list” and opting to establish stricter rules than 70% for setting the fee cap. Therefore, member states may use additional implementing legislation to deal with the options available. On May 10, 2016, the German Parliament (Bundestag) passed a law on the execution of the EU regulation for PIEs (Abschlussprüfungsreformgesetz) that included derogation from the prohibition of valuation and certain tax services on the “black list.” The new law came into force on June16, 2016 (Deutscher Bundestag, 2016).

- 5 Case law refers to “a contract with a protective effect for third parties.”

- 6 Although the Chamber is constituted by law and is supervised by the public body Auditor Oversight Commission (AOC) (later the Auditor Oversight Board [AOB]), the Chamber is operated and governed by the profession.

- 7 In June 2016 a new public body, the AOB, took over the AOC's inspection responsibilities and the AOB employs its own inspectors.

- 8 The Code refers to legal terms such as “beyond audit activities,” “in a responsible position,” “autonomous,” “material effect,” “minor relevance,” and “material activity.” These terms are not well defined, and this, together with the partly principle-based approach in the Code, makes the constitution of a legal NAS open to interpretation.

- 9 Financial statements of listed companies have to be published at the latest 4 months after the balance sheet date in the electronic Federal Gazette. Since 2009, all large corporations are obliged to disclose auditor fees in the notes to the financial statements.

- 10 This and other empirical archival research generally measures the net effect of auditor-provided NAS from threats to auditor objectivity and knowledge spillover benefits.

- 11 See Ghosh et al. (2009, p. 372) for a discussion of research design issues and arguments for the use of a 1-year measurement period (long window).

- 12 In line with the arguments in the research literature, regulators have suggested that investors would view audit-related tax services more favorably than other NAS (Securities and Exchange Commission, 2002, 2003).

- 13 Other studies examining the effect of the provision of tax NAS on planned audit hours or other audit planning decisions do not support the existence of audit production efficiencies from knowledge spillover (Davis, Ricchiute, & Trumpeter, 1993; Johnstone & Bedard, 2001; O'Keefe, Simunic, & Stein, 1994).

- 14 An EC Green Paper issued in 2010 forwarded what regulatory changes might be needed (EC, 2010). The Green Paper raised fundamental questions about the suitability and adequacy of the current legislative framework and signaled possible radical reinforcing of the prohibitions of NAS by audit firms (Quick, 2012). In 2011 the Commission proposed specific requirements regarding audits of PIEs (EC, 2011). The proposals included a general prohibition of the provision of NAS to PIEs clients; that is, a ban on services beyond the audit and related financial audit services.

- 15 Observations were excluded because of non-disclosure of NAS-fees (234), non-IFRS reporting (178), fiscal year ending other than 31 December (386), and joint audits (11).

- 16 The restrictive legal ban on providing tax NAS to PIE audit clients in Germany may limit tax NAS, compared with Anglo-American environments such as the USA; for example, Huang et al. (2007) report a tax–fee ratio of 15%.

- 17 Other studies that use interactions to investigate how NAS affect ERC include, among others, Krishnan et al. (2005), Gul et al. (2006), Ghosh et al. (2009), and Eilifsen & Knivsflå (2013). The inclusion of interaction terms in the regression models implies multicollinearity by construction. Nevertheless, when collinear variables are significant, as in our case, collinearity in itself does not present a problem, despite corrective variance inflation (Wooldridge, 2009, 95–99). Inspection of Table 2, panel B, of correlation coefficients between variables included in interaction terms (below 0.8) and variance inflation indicators (below 10 for all variables, except for EARN), do not indicate serious multicollinearity problems (Field, 2014, p. 325). For both regression models (5) and (6), the Durbin–Watson test statistics are close to 2.0 (1.973 and 1.977) and do not indicate presence of autocorrelation. Visual inspection of the plotted residuals does not reveal a heteroskedasticity problem. Further visual inspections reveal a normal distribution of residuals.

- 18 The results are qualitatively similar to those reported when winsorizing variables at 1% at each tail.

- 19 To investigate the robustness of the results, we perform additional tests by changing the specification of our empirical model (additional control variables) and using alternative nonaudit fee definitions. The insignificant results for the test variables are upheld.

- 20 For the pre-crisis period, the control variable the market-to-book value of equity (MBV) associates with ERC (0.026 with p = 0.085). During the crisis, there is a positive effect on ERC of STDRET (4.513 with p = 0.000) and a negative effect of MBV (−0.057 with p = 0.022) and LOSS (−1.030 with p = 0.000). For the post-crisis period, a negative effect on ERC is found for LOSS (−0.120 with p = 0.065), SIZE (−0.051 with p = 0.002), and BIG4 (−0.146 with p = 0.025).

- 21 This is in line with the predictions of hypotheses 2(a), 2(b) (investor perceptions are associated with the magnitude of auditor-provided assurance NAS, NAF1, and tax NAS, NAF2), and 2(c) (investor perceptions are negatively associated with the magnitude of auditor-provided other NAS, NAF3).

- 22 This in line with hypotheses and but not hypothesis .

- 23 This in line with hypothesis but not hypotheses and .

- 24 NAS fees before and after the crisis are significantly different (NAF: p = 0.000; NAF1: p = 0.085; NAF2: p = 0.000; NAF3: p = 0.000).

- 25 The truncation is comparable to excluding company-year observations when the total NAS fee is more than 70% of the annual audit fee.

- 26 Germany and most other EU member states decided not to deviate from the EU upper limited cap, while Poland and Portugal opted to lower the cap below 70%.

APPENDIX 1: GERMAN PROHIBITION OF THE PROVISION OF NONAUDIT SERVICES FOR ALL STATUTORY AUDITS IN OUR SAMPLE PERIOD

- Participation in bookkeeping and the preparation of the financial statements.

- Participation in internal auditing in a responsible position.