Variation in body mass dynamics among sites in Black Brant Branta bernicla nigricans supports adaptivity of mass loss during moult

Abstract

Birds employ varying strategies to accommodate the energetic demands of moult, one important example being changes in body mass. To understand better their physiological and ecological significance, we tested three hypotheses concerning body mass dynamics during moult. We studied Black Brant in 2006 and 2007 moulting at three sites in Alaska which varied in food availability, breeding status and whether geese undertook a moult migration. First we predicted that if mass loss during moult were simply the result of inadequate food resources then mass loss would be highest where food was least available. Secondly, we predicted that if mass loss during moult were adaptive, allowing birds to reduce activity during moult, then birds would gain mass prior to moult where feeding conditions allowed and mass loss would be positively related to mass at moult initiation. Thirdly, we predicted that if mass loss during moult were adaptive, allowing birds to regain flight sooner, then across sites and groups, mass at the end of the flightless period would converge on a theoretical optimum, i.e. the mass that permits the earliest possible return to flight. Mass loss was greatest where food was most available and thus our results did not support the prediction that mass loss resulted from inadequate food availability. Mass at moult initiation was positively related to both food availability and mass loss. In addition, among sites and years, variation in mass was high at moult initiation but greatly reduced at the end of the flightless period, appearing to converge. Thus, our results supported multiple predictions that mass loss during moult was adaptive and that the optimal moulting strategy was to gain mass prior to the flightless period, then through behavioural modifications use these body reserves to reduce activity and in so doing also reduce wing loading. Geese that undertook a moult migration initiated moult at the highest mass, indicating that they were more than able to compensate for the energetic cost of the migration. Because Brant frequently change moult sites between years in relation to breeding success, the site-specific variation in body mass dynamics we observed suggests individual plasticity in moult body mass dynamics.

Moult is an essential life history process in birds because feathers wear and lose effectiveness for flight and insulation. Replacing feathers is energetically costly, with demands for protein and energy to synthesize feather structure and drive the physiological changes that accompany moult (Kendeigh et al. 1977, Dol'nik & Gavrilov 1979, Heitmeyer 1988, Guillemette et al. 2007). Birds use widely varying strategies, apparently to accommodate the energetic demands (Palmer 1972, King 1974) and the reduced flight capability (Swaddle et al. 1999, Fox & Kahlert 2000) associated with moult. However, the physiological and ecological significance of these strategies is poorly understood.

In contrast to most birds, which replace flight feathers sequentially so as to maintain flight, waterfowl (Anatidae) and some other waterbirds [grebes (Podicipedidae), coots (Fulica spp.), divers (Gaviidae) and auks (Alcidae)] typically shed their flight feathers simultaneously and as a result undergo a period of flightlessness. During moult, birds experience an increased metabolic rate (Guillemette et al. 2007, Portugal et al. 2007) and compensatory changes in flight muscles and leg muscles (Ankney 1979, 1984, Raveling 1979, Brown & Saunders 1998). Waterfowl have relatively heavy bodies and small wing size, which results in high wing loading, and the loss of even one or two primaries can therefore result in reduced flight capability (Woolfenden 1967). Thus, moulting all flight feathers at once may be the most efficient strategy because it minimizes the flightless period; however, this strategy also results in heightened short-term protein and energetic demands as a result of increased moult intensity (King 1974, Heitmeyer 1988, Guillemette et al. 2007, Portugal et al. 2007). Furthermore, flightlessness may decrease feeding efficiency because of restricted foraging range and increased risk of predation (Sterling & Dzubin 1967, Owen & Ogilvie 1979). Given the nutritional demands and limited flexibility in feeding opportunity, the study of body mass dynamics during moult has provided insight into the energetics of moult in waterfowl (Hohman et al. 1992). However, major uncertainties remain in relation to limitations in nutrient acquisition and nutrient allocation during flightless moult. Studies of geese may be particularly informative because these requisite herbivores are relatively small bodied, which limits processing efficiency of food (Demment & Van Soest 1985). In addition, the plant foods of geese have a relatively low nutrition to fibre ratio and often lack some essential amino acids (Sedinger 1984, 1997, Sedinger & Raveling 1988).

Waterfowl often move away from breeding grounds to special areas to moult (moult migration; Salomonsen 1968), a behaviour probably linked to the specialized needs of flightlessness. In geese, moult migrants are made up exclusively of failed breeders and non-breeding birds, whereas successful breeding birds are constrained to moult while attending their flightless young because the timing of moult overlaps the brood-rearing period.

Mass loss during moult has been documented by numerous studies of ducks and geese (e.g. Hanson 1962, Owen & Ogilvie 1979, Sjöberg 1988, Fox & Kahlert 2005), whereas other studies have shown that mass can remain stable during moult (e.g. Ankney 1979, 1984, Raveling 1979, Fox et al. 1998). This inconsistent pattern is also apparent within species; during moult, mass decreased at one site and remained stable at another in Black Brant Branta bernicla nigricans (Ankney 1984, Taylor 1995, Lewis et al. 2011). Hypotheses that have been proposed to explain body mass dynamics during moult generally fall into two categories: adaptive and non-adaptive. The primary non-adaptive hypothesis proposes that mass loss is simply the result of waterfowl being unable to meet the energetic requirements of self-maintenance and wing moult solely from diet (i.e. inadequate food hypothesis; Hanson 1962, Moorman et al. 1993, Fox & Kahlert 2005, Lewis et al. 2011). In contrast, two other hypotheses propose that mass loss during moult is adaptive. Prior to moult, some ducks and geese accumulate lipid reserves (Ankney 1979, 1984, Mainguy & Thomas 1985, Panek & Majewski 1990, Fox et al. 1998) and during the flightless period change their behaviour, including reduced feeding and general maintenance and increased secretiveness and periods of inactivity (Owen & Ogilvie 1979, Moorman et al. 1993, van de Wetering & Cooke 2000, Portugal et al. 2007, 2011). The activity reduction hypothesis proposes that lipid stores are accumulated prior to moult and then adaptively used during moult to reduce predation risk by allowing birds to reduce feeding activities (Panek & Majewski 1990, Kahlert et al. 1996, Fox et al. 1998, Portugal et al. 2007, 2011). Lastly, some waterfowl are capable of flight prior to the completion of feather regrowth (Boyd & Maltby 1980, Ankney 1984, Taylor 1995). The wing load reduction hypothesis proposes that mass loss during moult is adaptive in that it reduces wing loading and so allows the lighter birds to regain the ability to fly sooner (Douthwaite 1976, Owen & Ogilvie 1979).

The aim of our study was to examine evidence supporting or refuting these hypotheses concerning body mass dynamics during moult. Under the inadequate food hypothesis we predicted that geese would lose the most mass where food was least available. Under the activity reduction hypothesis it is advantageous for geese to enter moult with high body mass and to reduce activity as much as possible by using reserves. Thus, we predicted that geese would initiate moult with the highest mass where food was most available and lose the most mass where mass at the initiation of moult was highest. Under the wing load reduction hypothesis we predicted that across sites, mass at the end of the flightless period would converge on a theoretical optimum mass that permitted the earliest possible return to flight. We studied moulting Pacific Black Brant Branta bernicla nigricans (hereafter Black Brants) at three sites: (1) successful breeding geese at a brood-rearing area near their nesting colony, (2) failed and non-breeding geese at a moult area adjacent to breeding grounds and (3) failed and non-breeding geese that migrated to a moult area away from the breeding grounds. This sampling design allowed us to compare geese moulting at sites that varied in food availability (Sedinger et al. 2001, Lake et al. 2008, P. Flint & J. Schmutz unpubl. data) and to compare geese that varied in breeding success and whether they undertook a moult migration, all factors that could influence moult body mass dynamics (Ankney 1979, 1984, Owen & Ogilvie 1979, Raveling 1979, Taylor 1995, van der Jeugd et al. 2003). The Black Brant occurring at these three moulting sites were primarily from the same breeding population (Bollinger & Derksen 1996), which facilitates contrasts of different behaviours within the population. We examined the age structure, sex ratio, moult phenology, breeding status and origin of birds moulting at each site. We also compared body mass at the initiation of moult and at the end of the flightless period, and rates of change in body mass during moult. We then evaluated our results in terms of our predictions for each hypothesis.

Methods

Study sites

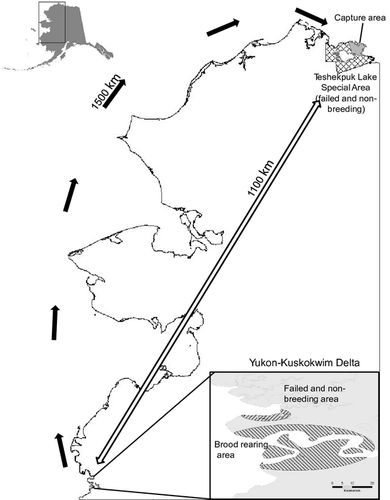

In 2006 and 2007, we sampled moulting Black Brant at two sites at their primary breeding area (Sedinger et al. 1993), the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta (YKD), and at one site on the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area (TLSA), the primary moulting area for Black Brant (up to 25% of the Pacific Flyway population; Flint et al. 2008) on the arctic coastal plain of Alaska (> 1000 km north of YKD). The first YKD moult site was a brood-rearing area used by successful breeding geese and their goslings after dispersing up to 25 km (Fondell et al. 2011) from nest-sites within the Kigigak Island and Baird Inlet nesting colonies (YKD-BR; 60°N, 164°W; Fig. 1). The second YKD moult site was an area used by failed breeders and non-breeding geese (YKD-FN; 60°N, 164°W), adjacent to YKD-BR. This area held the only known aggregation of moulting failed and non-breeding Black Brant on YKD (about 1500 geese; T. Fondell & C. Nicolai unpubl. data). Both YKD study sites were within 2 km of the coast in tidally influenced salt marsh vegetation interspersed with tidal sloughs, small ponds and mudflats. The third moult site was in the northeast section of TLSA (70°N, 152°W), where most moulting Black Brant have traditionally occurred (King 1970, Derksen et al. 1979). The TLSA is an area where failed and non-breeding Black Brant migrate to moult, originating largely from nesting colonies across Alaska, but also Western Canada and Eastern Russia (Bollinger & Derksen 1996). While estimates of the proportional representation of the origins of Black Brant moulting on TLSA are lacking, local breeders can account for only a small proportion (Mallek 2009, Larned et al. 2010). The YKD is the most likely origin; it is where > 60% of Pacific Flyway Black Brant nest (Sedinger et al. 1993) and the number of Black Brant moulting on TLSA is inversely related to nesting propensity and nest success on YKD (Ritchie et al. 2009). Moulting habitat on TLSA was dominated by large thaw lakes and tundra vegetation underlain by continuous permafrost, as well as coastal areas dominated by salt-tolerant sedges (Derksen et al. 1982, Jorgenson et al. 2006, Flint et al. 2008).

We did not measure goose food as part of this study. However, over the period of our study, gosling growth rates were very low at YKD-BR (Fondell et al. 2011) and growth rates are a sensitive indicator of food availability (Cooch et al. 1993, Lindholm et al. 1994). In addition, since the early 1990s at sites across YKD occupied by geese, studies have consistently found that goose foods were heavily grazed, with 80–95% of net above-ground primary productivity removed, and that gosling growth rates were often low as a result (Person et al. 1998, Schmutz & Laing 2002, Person & Ruess 2003, Lake et al. 2008, J. Schmutz unpubl. data). In contrast, on areas of the arctic coast adjacent to TLSA, growth rates of Black Brant goslings were considerably higher because of greater availability of food (Sedinger et al. 2001). Furthermore, throughout the period 2000–2010, plant biomass has consistently differed little between plots protected from goose grazing and unprotected plots (P. Flint & J. Schmutz unpubl. data). In addition, salt-water inundation on TLSA has resulted in shifts in the moulting distribution of geese, probably because of expanded areas of preferred foods (Flint et al. 2008). We interpret this to indicate that over the period of our study, per-capita food availability was low at YKD-BR and the adjacent YKD-FN, and higher at TLSA.

Field methods

We captured moulting Black Brant by herding them into corral traps (Bollinger & Derksen 1996). We determined sex by cloacal examination and distinguished second year (SY) from after second year (ASY) birds based on the colour of the tips of the middle-wing coverts (Harris & Shepherd 1965). Female Black Brant were categorized as breeding or non-breeding based on the presence or absence of a brood patch. We considered females with a brood patch captured at YKD-BR as successful breeding geese and those captured at the other two sites (where no goslings were observed) as failed breeders. ASY males captured at YKD-BR were considered likely to be successful breeding geese and those captured at the other two sites as probably failed or non-breeding geese. Birds were weighed using an electronic balance (± 1.0 g). The length of the 9th (longest) primary was used as an index of moult stage (Owen & Ogilvie 1979, Ankney 1984, Taylor 1995). We measured the 9th primary by inserting a ruler between the 8th and 9th primaries and measuring from the skin at the base to the distal end (± 1.0 mm). Culmen and tarsus were measured using callipers (± 0.1 mm). Black Brant with unmoulted 9th primaries, which were identifiable due to wear, were considered to be in pre-moult and given a primary feather measure of 0. Due to scheduling and logistical constraints, Black Brant were captured earlier at TLSA (18–22 July and 16–19 July in 2006 and 2007, respectively) than at the two YKD areas (22–27 July and 23–28 July). To assess mass gain prior to moult we captured and weighed (using an electronic balance; ± 1.0 g) incubating females 0–3 days prior to hatch at the Kigigak Island and Baird Inlet nest colonies. For descriptions of nest searching techniques, see Fondell et al. (2011).

Prior to our study, Black Brant had been ringed in large numbers at YKD and TLSA, and in smaller numbers in arctic Canada and Russia (Sedinger et al. 2007). We determined previous capture locations for all Black Brant we recaptured. Because ringing effort varied among sites, the number of recaptures is not a proportional representation of the site of origin. Therefore, we did not conduct a formal analysis but simply describe movements between moult sites.

Statistical analysis

We used GLM univariate analysis of variance procedures in spss 12.0 (SPSS Inc. 2003) to fit models of variation in body mass dynamics during moult. Models were compared using Akaike's information criterion (AIC), with the best model being the model with the lowest AIC (Burnham & Anderson 2002). We used parameter weights (wi) and the degree to which 85% confidence intervals (CIs) around parameter estimates overlapped 0 to evaluate the strength of evidence for individual parameters (Burnham & Anderson 2002, Arnold 2010). We included the covariate 9th primary length (9TH) as an index of moult stage. We also included a size parameter (log (tarsus)/100 + log (culmen)/100; SIZE) to account for variation in body mass (MASS) with body size; both tarsus and culmen were log-transformed prior to summing to minimize differences in scale. Thus, our analysis functionally examined variation in mass, adjusted for moult stage and structural body size. We included YEAR, SEX and AGE as fixed factors because previous studies of moulting Black Brant had shown them to be important (Boyd & Maltby 1980, Ankney 1984, Taylor 1995, Lewis et al. 2011). Our main interest was in whether patterns of mass at the start of moult and mass loss during moult differed among sites (SITE); therefore we compared models that included SITE with those that did not. Given the large number of potential models, we used an exploratory analysis to determine the most appropriate model structure for our categorical variables. In the exploratory analysis we used all parameters as main effects but only categorical parameters (YEAR, SEX, AGE and SITE) to build interaction terms. Our least parameterized model in the exploratory analysis included SIZE, 9TH, YEAR, SEX and AGE. To our second model in the exploratory analysis we added the parameter SITE and for the remaining 11 models we included an interaction term consisting of the various combinations of SEX, AGE, YEAR and SITE. We then used the best model from the exploratory analysis as the least parameterized model in our primary analysis. This first model implies that there is no variation in the rate of mass loss among SEX, AGE, YEAR and SITE. For each of the subsequent 14 candidate models in our primary analysis, we added an interaction term that included the covariate 9TH with all possible combinations of SEX, AGE, YEAR and SITE.

We calculated date of moult initiation for each bird by dividing the 9th primary length by the daily feather growth rate and subtracting this from the date of capture. Two relevant estimates of feather growth exist: Taylor (1995; 7.2 ± 0.1 mm per day) took multiple measures of individual Black Brants moulting on TLSA, sampling all age and sex groups, and Singer et al. (2012; 5.0 ± 0.6 mm) estimated feather growth using linear models of moult on YKD sampling ASY brood-rearing females only. Comparison of the two feather growth rates is probably confounded because estimation methods and sample design differed. The Singer et al. (2012) estimate was lower than any previous estimate reported for geese (range 6.0–8.1 mm; reviewed in Hohman et al. 1992, Taylor 1995). Therefore, we calculated moult initiation date for all sites using the estimate from Taylor (1995) and for comparison calculated a second date for both YKD sites using the estimate from Singer et al. (2012). We estimated marginal means (85% CIs) of MASS for the beginning (9TH = 0 mm) and end of the flightless period (9TH = 158 mm; Black Brant regain flight when the 9TH is approximately 70% of the final length, 154 mm in females and 161 mm in males; Taylor 1995), and estimated rates (85% CIs) of MASS change during wing moult using model averaging (Burnham & Anderson 2002).

Results

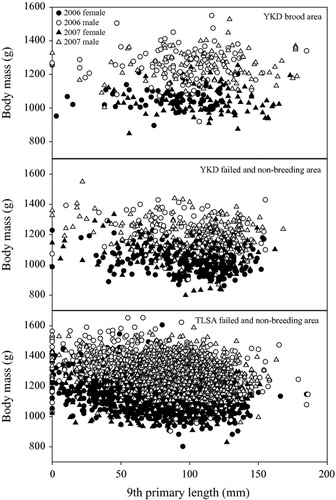

During 2006 and 2007 we assessed age, sex and breeding status of 880, 834 and 4050 moulting Black Brant and of these we obtained mass and structural measures of 355, 730 and 3782 at YKD-BR, YKD-FN and TLSA, respectively. At YKD-BR, geese were almost exclusively ASY and almost all females had brood patches, although a small number of SY and ASY non-breeding geese were also present (Table 1). YKD-FN and TLSA had similar proportions of females with brood patches; however, YKD-FN appeared to have a larger proportion of females, both SY and ASY, compared with TLSA. The moult stage of sampled Black Brant differed between sites in both 2006 and 2007; mean 9TH was 89.3 ± 2.3 mm and 112.2 ± 2.4 mm at YKD-BR, 100.4 ± 1.5 mm and 101.4 ± 1.7 mm at YKD-FN, and 80.4 ± 0.8 mm and 86.0 ±0.6 mm at TLSA. However, the range of moult stage measures broadly overlapped among sites, in both 2006 and 2007 (Fig. 2). Thus, among-site variation in moult stage probably does not confound our comparison of body mass dynamics of moulting Black Brant.

| Site | n | After second year | Second yeara | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % F | % F w/BPb | % | % F | ||

| YKD-BR | 880 | 94 (3) | 48 (2) | 96 (1) | 6 (3) | 78 (3) |

| YKD-FN | 834 | 65 (6) | 55 (6) | 74 (6) | 35 (6) | 66 (7) |

| TLSA | 4050 | 73 (6) | 45 (3) | 72 (5) | 27 (6) | 48 (3) |

- a Only one second year female had a brood patch.

- b Percentage females with a brood patch: considered to be successful breeding birds at YKD-BR and failed breeding birds at YKD-FN and TLSA. Those without a brood patch were considered non-breeders.

Of the previously ringed Black Brant recaptured at YKD-BR (n = 91) and at YKD-FN (n = 41), most originated from YKD (78 and 90%, respectively), where they had been ringed as breeding adults or goslings. Some (22 and 10%, respectively) had also been captured or resighted moulting at a number of failed or non-breeding sites, including TLSA. Of the previously ringed geese recaptured at TLSA (n = 380), most originated from TLSA (77%). Some had also been captured or re-sighted breeding on YKD (11%) and others at failed and non-breeding moult sites beside TLSA (12%). Thus, individual Black Brant were generally faithful to moult sites but switching sites between years also commonly occurred.

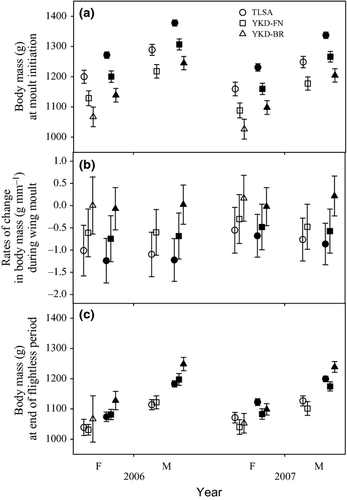

The two best models (models 1 and 2; Table 2) explaining variation in body mass during moult received nearly all support (combined wi = 0.99). Both included SITE as a main effect, indicating that body mass varied among sites at moult initiation. Marginal means of MASS at the initiation of moult differed between sites and in a consistent manner, being highest at TLSA (where food was most available), intermediate at YKD-FN and lowest at YKD-BR (Fig. 3a).

| Model | Devianceb | K c | AIC | ΔAIC | w i d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EXPLOR, SEX*YEAR*SITE*9TH | 32 118 455.4 | 21 | 42 845.9 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| 2. EXPLOR, SEX*YEAR*AGE*SITE*9TH | 31 977 007.3 | 32 | 42 846.4 | 0.5 | 0.43 |

| 3. EXPLOR, YEAR*SITE*9TH | 32 253 955.2 | 15 | 42 854.3 | 8.5 | 0.01 |

| 4. EXPLOR, SEX*AGE*SITE*9TH | 32 299 048.2 | 21 | 42 873.1 | 27.3 | 0.00 |

| 5. EXPLOR, AGE*SITE*9TH | 32 379 437.0 | 15 | 42 873.2 | 27.4 | 0.00 |

| 6. EXPLOR, SEX*SITE*9TH | 32 380 599.4 | 15 | 42 873.4 | 27.6 | 0.00 |

| 7. EXPLOR, SITE*9TH | 32 450 143.7 | 12 | 42 877.9 | 32.0 | 0.00 |

| 8. EXPLOR, SEX*YEAR*AGE*9TH | 32 599 058.0 | 17 | 42 910.1 | 64.3 | 0.00 |

| 9. EXPLOR, YEAR*AGE*9TH | 32 653 916.6 | 13 | 42 910.3 | 64.5 | 0.00 |

| 10. EXPLOR, SEX*YEAR*9TH | 32 693 482.3 | 13 | 42 916.2 | 70.4 | 0.00 |

| 11. EXPLOR, YEAR*9TH | 32 731 329.7 | 11 | 42 917.8 | 72.0 | 0.00 |

| 12. EXPLOR, AGE*9TH | 32 818 131.7 | 11 | 42 930.7 | 84.9 | 0.00 |

| 13. EXPLOR, SEX*AGE*9TH | 32 809 653.8 | 13 | 42 933.5 | 87.6 | 0.00 |

| 14. EXPLOR | 32 875 915.9 | 10 | 42 937.3 | 91.4 | 0.00 |

| 15. EXPLOR, SEX*9TH | 32 875 903.5 | 11 | 42 939.3 | 93.4 | 0.00 |

- a The length of the 9th primary used as an index of wing moult stage.

- b Residual sum of squares.

- c Number of model parameters.

- d AIC model weight.

The interaction term of the two top models also included SITE (Table 2). A model equivalent to the best model but without SITE in the interaction term (model 10) was not competitive (ΔAIC = 70.4). Model-averaged rates of mass change during wing moult differed among sites (Fig. 3b), being greatest between YKD-BR and TLSA (little overlap of 85% CIs) and less so at YKD-FN (85% CIs overlapped both YKD-BR and TLSA). Most rates were negative and thus a measure of mass loss. Mass loss was greatest at TLSA (where mass at moult initiation was greatest; Fig. 3a), intermediate at YKD-FN (where mass at moult initiation was intermediate; Fig. 3a) and lowest at YKD-BR (mass did not change; 85% CIs overlapped 0) (where mass at moult initiation was lowest; Fig. 3a). Thus, rates of mass loss were greater where mass at the initiation of moult was greater. At the end of the flightless period, among-site and between-year variation in marginal means of mass were greatly reduced in comparison with mass at moult initiation (Fig. 3a,3c).

Mean mass of adult female Black Brant at the initiation of moult was 102.4 g and 58.5 g greater at the YKD-BR brood area, 168.8 g and 125.0 g greater at YKD-FN, and 235.0 g and 191.1 g greater at TLSA than that of nesting females captured late in incubation on YKD [1038.7 ± 8.8 g and 1047.6 ± 14.0 g] in 2006 and 2007, respectively. Using the feather growth estimates of Taylor (1995), moult initiation dates were latest at YKD-BR, 6.1 ± 0.4 days and 1.1 ± 0.4 days later than YKD-FN, and 6.3 ± 0.4 days and 4.9 ± 0.3 days later than TLSA in 2006 and 2007, respectively. Using the feather growth estimates of Singer et al. (2012), moult initiation dates at YKD-BR differed little from TLSA (≤ 1.5 ± 0.3 days) in both years and were later than at YKD-FN in 2006 (6.9 ± 0.6 days) but not in 2007 (0.5 ± 0.6).

Discussion

Our study is the first to compare moult body mass dynamics among multiple sites where food availability, breeding status and migratory status of moulting birds differed. We found that sites varied with respect to changes in body mass during moult. Black Brant show general fidelity to a moult site, but between-year switches also occurred (Ward et al. 1993, Bollinger & Derksen 1996, this study). In geese, successful breeding birds are constrained to moult close to nesting areas, whereas failed breeders and non-breeding geese can move elsewhere and often undertake a moult migration (Salomonsen 1968). This ability to switch moult sites suggests plasticity in body mass dynamics during moult, manifested in response to a change in breeding status.

One assumption of our study was a linear relationship between 9th primary length and the number of days since moult was initiated (Owen & Ogilvie 1979, Ankney 1984, Taylor 1995). This relationship could in fact be more complicated because growth rates of remiges may not be consistent with feather length (Owen & King 1979, Taylor 1995), body mass (van de Wetering & Cooke 2000, but see Taylor 1995) or date of replacement (Smart 1965, but see Panek & Majewski 1990). Non-linearity appeared to be weak in studies of moulting Black Brant on TLSA (Taylor 1995) and on YKD (Singer et al. 2012); variation in primary length was predominantly explained by moult stage, with only weak effects of variation in growth rates. Furthermore, even if the relationship is individually non-linear, our linear models should still reflect differences between groups.

Inadequate food hypothesis

Early studies demonstrated significant mass loss by moulting waterfowl and led researchers to suggest that moult was a period of nutritional stress, potentially resulting in reduced survival (Hanson 1962). Further study revealed that in some cases moulting geese did not lose mass (Ankney 1979, 1984, Raveling 1979) and that the atrophy of flight muscle and the hypertrophy of leg muscle were largely compensatory, with no overall net change in locomotor musculature (Ankney 1979, 1984, Fox & Kahlert 2005, Portugal et al. 2007). At present, researchers generally agree that moult is not nutritionally stressful in the sense of reducing fitness (Hohman et al. 1992). However, where mass loss occurs there is continued disagreement as to whether it reflects local habitat conditions and an inability to meet energetic requirements solely from the diet (Fox et al. 1998, Fox & Kahlert 2005, Kahlert 2006, Lewis et al. 2011). Under the inadequate food hypothesis we predicted that mass loss should be negatively related to food availability. We found the opposite; mass loss was greatest at TLSA, where food was most available, and lowest at YKD-BR, where growth rates of goslings were very low (i.e. strong evidence of limited food resources; Fondell et al. 2011). We therefore reject the inadequate food hypothesis; Black Brant appeared to meet their energetic demands from their diet even where food availability was low. In addition, although moult may be energetically costly (Kendeigh et al. 1977, Dol'nik & Gavrilov 1979, Heitmeyer 1988), energy demands of self-maintenance are likely to be reduced for moulting geese. This is because of behavioural and physiological changes, such as flightlessness and, for failed breeders and non-breeding geese, lowered activity levels (Owen & Ogilvie 1979, van de Wetering & Cooke 2000, Guillemette et al. 2007, Portugal et al. 2007, 2011).

Activity reduction hypothesis

The reduced activity hypothesis proposes that birds reduce activity during moult by adaptively using lipid reserves and in so doing reduce exposure to predators (Panek & Majewski 1990, Kahlert et al. 1996, Fox et al. 1998, Portugal et al. 2007, 2011). Prior to the initiation of wing moult, ducks (Panek & Majewski 1990, Brown & Saunders 1998, Fox & King 2011) and geese (Ankney 1979, 1984, Mainguy & Thomas 1985, Portugal et al. 2007) often gain mass in the form of lipid reserves. During moult, mass loss results almost exclusively from the mobilization of lipid reserves (Young & Boag 1982, Loonen et al. 1991, 1997, Fox et al. 1998). With the initiation of wing moult, activity levels in waterfowl often decrease, including decreased feeding in both wild (Owen & Ogilvie 1979, Bailey 1985, DuBowy 1985, Austin 1987, Fox & Kahlert 1999, Adams et al. 2000, Kahlert 2006) and captive birds (Pehrsson 1987, Portugal et al. 2007), with the heaviest birds spending the greatest proportion of their time resting (Portugal et al. 2011). Our results, like several previous studies (van de Wetering & Cooke 2000, van der Jeugd et al. 2003, Portugal et al. 2007), fit predictions for this hypothesis; mass loss during moult was greatest where mass at moult initiation was greatest. Furthermore, consistent with previous findings it appeared that Black Brant in our study gained mass prior to moult; the mass of ASY females at the initiation of moult was greater than the mass of ASY females we captured in late incubation. Geese nesting at northern latitudes typically reach their lowest level of stored reserves at the end of incubation (Ankney 1979, 1984, Raveling 1979, Mainguy & Thomas 1985). Finally, TLSA Black Brant were heaviest at moult initiation and lost the most mass during moult, despite access to the best food resources, which suggests that moulting geese on TLSA reduced feeding during moult.

Wing load reduction hypothesis

While flightless, waterfowl are likely to be under increased risk of predation (Douthwaite 1976, Owen & Ogilvie 1979) and have limited access to food (Panek & Majewski 1990, Kahlert et al. 1996, van de Wetering & Cooke 2000, Lewis et al. 2010a). Because waterfowl (Sjöberg 1988, Taylor 1995, Brown & Saunders 1998) can regain flight when remiges are 70–80% of the final length, birds may adaptively lose mass during moult to reduce wing loading and thereby regain flight sooner. Consistent with previous studies (van de Wetering & Cooke 2000, van der Jeugd et al. 2003, Portugal et al. 2007), our results fit predictions for the wing load reduction hypothesis; heaviest birds at moult initiation lost the most mass during moult and within age and sex groups body mass appeared to converge at the end of the flightless period (see also van der Jeugd et al. 2003). In contrast, Lewis et al. (2011) did not find evidence of convergence at the end of moult among sub-groups within TLSA, which may be a function of scale and the degree of variation apparent among, as opposed to within, moulting areas.

The activity reduction and the wing load reduction hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive. We were unable to distinguish between them because the pattern of our results fitted both adaptive hypotheses; specifically, the site where geese were heaviest at moult initiation was also that at which geese lost the most mass during moult and where food was most abundant. In addition, mass at the end of moult converged across all sites. Both hypotheses suggest that mass loss during moult is adaptive and it may be that body mass dynamics represent a balance between acquiring adequate reserves prior to moult to allow birds to reduce activity, but not in excess of what can be lost, and still regain flight as early as possible. These hypotheses also relate directly to the conservation value of the areas used for moult. For example, the TLSA where Black Brant lost the most mass would have a relatively low value under the inadequate food hypothesis and a relatively high value under the reduced activity hypothesis.

At the initiation of moult, Black Brant at TLSA were heavier than geese moulting at YKD, despite the additional cost that the majority of the geese incurred in migrating to the TLSA (Bollinger & Derksen 1996, Mallek 2009, Larned et al. 2010); the most likely source of geese moulting on TLSA was YKD (Sedinger et al. 1993), > 1100 km away. This difference was likely to be because of better feeding conditions on TLSA which allowed geese to acquire larger pre-moult reserves. Under the reduced activity hypothesis it would follow that one advantage of undergoing the moult migration to TLSA was improved pre-moult condition. Also, greater mass at moult initiation has been linked to faster remigial growth rates in male Barrow's Goldeneye (Bucephala islandica; van de Wetering & Cooke 2000). Greater body reserves or higher food availability may explain an apparent faster rate of remigial growth at TLSA (Taylor 1995) than at YKD-BR (Singer et al. 2012) in Black Brant. If true, another advantage of moult migration would be reduced length of the flightless period. When birds acquire pre-moult reserves, habitats used prior to moult influence body mass dynamics and, in turn, survival during moult. On TLSA, Black Brant arrive 7–10 days prior to initiating moult (Derksen et al. 1982, Taylor 1995) and during this period Black Brant visited on average four wetlands, probably to ‘prospect’ potential moult sites (Lewis et al. 2010b). We suggest that pre-moult movements also allow Black Brant to locate areas with high-quality food to build fat reserves for the flightless period.

The timing of moult and body mass dynamics is probably under differing selection constraints in relation to breeding status. We found that failed and non-breeding geese began moult earlier than those rearing young; similar to previous studies (Newton 1977, Loonen et al. 1991, van der Jeugd et al. 2003), differences are greatly reduced if feather growth rates are slower at YKD (Singer et al. 2012). Brood-rearing Black Brant initiate moult 15–20 days after hatch (Singer et al. 2012), a period that we suggest is related to brood care and gosling development. First, a full wing is likely to be advantageous throughout the 10–14-day brooding period (Afton & Paulus 1992). Secondly, by delaying moult, adults are better able to protect young during the first 15 days when most mortality in Black Brant goslings occurs (Flint et al. 1995) allow adults to retain the ability to migrate until after the high-risk period is over. Thirdly, by delaying moult, adults regain flight (approximately 23 days after initiating moult; Taylor 1995) at roughly the same time as young become flighted (Black Brant goslings fledge at 40–45 days; Reed et al. 1998). The delay may also allow geese to regain some fat reserves prior to moult (Singer et al. 2012); similar to previous studies (Ankney 1979, 1984, Raveling 1979, Mainguy & Thomas 1985) we found that moulting brood-rearing geese gained mass prior to moult, but the increase was relatively small (< 100 g). Furthermore, at the end of the flightless period, brood-rearing adults were generally heavier than failed and non-breeding geese (see also Owen & Ogilvie 1979), suggesting that the advantages of regaining flight early may be reduced for adults rearing goslings.

Work on YKD was largely funded by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Alaska Science Center, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and their partners as part of the monitoring and detection program me for highly pathogenic avian influenza in wild birds. The staff of the Yukon-Delta National Wildlife Refuge provided logistical assistance. Work at TLSA was funded by the USGS. The USFWS, Region 7, Division of Migratory Bird Management provided aerial support and assisted with goose captures. We thank the field assistants, too numerous to list, who helped out in the capture and handling of geese. D. Derksen provided advice during project planning. Editorial comments from M. Bolton, T. Lewis, R. Nager, J. Pearce, S. Portugal and an anonymous reviewer greatly improved the quality of this manuscript. The capture and handling protocol was approved by the USGS, Alaska Science Center Animal Care and Use Committee, under protocol 06-SOP-02. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.