Developing a typology of mobile phone usage in social care: A critical review of the literature

Funding Source

Seed money from School of Healthcare, University of Leeds.

Abstract

The ways in which mobile phones have transformed the boundaries of time and space and the possibilities of communication have profoundly affected our lives. However, there is little research on the use of mobiles in social care though evidence is emerging that mobile phones can play an important role in delivering services. This paper is based on a scoping review of the international literature in this area. A typology of mobile interventions is suggested. While most mobile phone interventions remain unidirectional and sit within traditional social care service provider–service user relationships, a minority are bi- or multidirectional and contain within them the potential to transform these traditional relationships by facilitating a collective development of social networks and social capital. Such transformations are accompanied by a range of issues and dilemmas that have made many service providers reluctant to engage with new technologies. We suggest that our typology is a useful model to draw on when researching the use of mobile phones in social care to support and empower isolated, marginalised and vulnerable service users.

What is known about this topic

- Mobile phones, which have achieved very widespread use in many societies, have created new spaces for communication that transcend spatial and temporal locations, transforming many social practices including health and social care.

- There is evidence of a digital divide with some social groups excluded from this communication revolution.

- Mobile technologies have the potential to challenge traditional servicer user—service provider hierarchies, raising profound questions about how professionals manage their relationships with service users.

What this paper adds

- While the use of mobile technologies associated with some health outcomes has been relatively well researched, this paper identifies a lack of robust knowledge about the use of such technologies in social care.

- This paper suggests a typology of mobile phone use distinguishing between uni-, bi- and multidirectionality highlighting the potential for bi- and multidirectional use to transform traditional service provide/service user relationships and providing a model for future research.

- This typology highlights the considerable potential for mobile technologies to enhance the social capital of isolated or marginalised service users and develop more empowering social networks.

1 INTRODUCTION: THE RISE OF MOBILE TECHNOLOGIES

The mobile phone is “arguably the most rapidly diffused technological artefact in history” (Wajcman, 2008, p. 68). The most recent data suggested that over 90% of adults in the UK had a mobile although only 66% had a “smartphone”—a phone powerful enough to act as an internet-enabled pocket computer (Ofcom, 2015). In some countries, including the UK, it has been suggested that there are rates of mobile phone ownership higher than 100% (Bittman, Brown, & Wajcman, 2009). Mobile phones have collapsed boundaries between work and leisure, and between our public and our private lives. Because mobile phones operate anywhere (provided there is a signal), they create spaces for communication that are not tied to physical locations and so many activities have been displaced from their traditional locations in time and space: they are “without borders” (Wajcman, Bittman, & Brown, 2008) particularly those between work/public time and private/leisure time. How people manage these increasingly blurred boundaries and use their mobile phones to negotiate social relationships, social roles and personal identity is the subject of a burgeoning literature almost all of which has been written since 2000 (Green & Haddon, 2009). The dizzyingly rapid and transformative developments in mobile technology and the sophisticated and creative ways users adapt the technology to their social needs make this an emergent and rapidly evolving field. These transformations permeate the “empirically specific social practices through which time and space are framed and apprehended on an everyday basis” (Green, 2002, p. 281).

Despite the figures cited above, there is evidence of a digital divide in the UK: the most recent data suggest that mobile phone usage ranges from 90% of 16- to 24-year olds to just 18% of those aged 65 and over (Ofcom, 2015). Similarly, while 11% of all UK adults had never used the Internet, 24% of those aged 65–74 and 61% of those aged 75 and over had never used it. About 27% of disabled people (based on self-assessment against the Equality Act definition) also reported never using the Internet. These data suggest that a significant minority of the population may be excluded from Internet-based interventions which can be accessed with a smartphone (e.g. messaging services such as Whatsapp and social media sites like Twitter and Facebook which are increasingly used for communication and group “chat”). The blurring of space-time boundaries and expectations of constant availability are not socially neutral: they affect people differently depending on their degree of control over their time and their social and professional status (Green, 2002).

The area of everyday social practice forming the focus of this paper is the use of mobile phones in social care. There have been overlapping developments in Internet-based interventions but the focus here is mobile phone activities involving calls, short message service (SMS) texts and messaging services. It should be noted, however, that insights from Internet-based interventions may have relevance for mobile phone interventions and some studies group Internet and mobile technologies under a broad “Information and Communications Technology” (ICT) label, meaning some joint consideration is necessary and useful.

There is now a body of research on the potential for mobile phone technology to improve preventative care and illness management in health-related fields, but much less on the use of mobiles in social work and social care and very little on the perspectives of service users, how the service provider/service user relationship might be altered, or the practice implications for professional social workers and third sector volunteers.

1.1 Background and research question

The genesis of this paper was a study undertaken by a Social Work MA student, supervised by one of this paper's authors, of the befriending relationships between volunteers for a local family support agency and their service users (Lawton, 2014). It became clear that the use of mobile phones played a significant role in developing these negotiated friendships which were based on the service users’ perceptions that befrienders were available, reliable and non-judgemental. Particularly important was the use of SMS texts which enabled service users to communicate and share information without having to speak to the volunteer when disclosing information they felt unable to share in face-to-face or telephone dialogue.

Funding was secured to explore the use of mobile communication technology in negotiating support relationships with service users through the following research questions:

- How are these relationships changing?

- What are the benefits and risks of mobile phone use in these relationships?

- What policies do agencies have to regulate their use?

- How effective are these policies?

This paper is based on the systematic scoping review of the literature which was undertaken as part of the study.

2 METHODS

This study was informed by Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) scoping review framework, as well as Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien's (2010) additional recommendations. An initial research question was developed based on the findings from the Masters study described in the introduction. Using this research question, search terms were developed from reading already-cited literature and following reference trails to relevant papers. Because of a diversity of terms used in different studies based on different fields (e.g. studies from healthcare versus those from psychology), as well as different terms in US and UK English, search terms were deliberately broad (see Table 1). Initial database searches were run and search terms refined in consultation with team members. Initial inclusion criteria were selected:

| Technology | Relationship | Service user |

|---|---|---|

| “mobile phone” OR “mobile device” OR “mobile communication” OR “mobile technolog*” OR “mobile media” OR “cell* phone” OR “cell* device” OR “cell* communication” OR “communication technolog*” OR “cell* technolog*” OR “cell* media” OR smartphone OR “social media” OR “personal communication device” | “support relationship” OR “therapeutic relationship” OR “dual relationship” OR befriending OR mentoring OR “emotional support” OR “social support” OR companionship OR “mutual support” OR “peer support” OR “home visit” | “service user” OR client OR “vulnerable adult” OR “vulnerable group” OR patient OR disabled OR disabilities OR “young people” OR “looked after children” OR “mental health” OR psychiatric OR carers OR “older people” OR elderly OR “senior citizen” |

- Papers available in English

- Peer-reviewed documents (including journal articles, book chapters, reviewed conference proceedings and theses).

- A date limit of 2005, given the rapid development of mobile technology and associated research in the ensuing years.

The full database searches were run 21–22 September 2015. The following databases were searched: Proquest (including ASSIA, IBSS, Proquest Dissertations and Theses, Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts); Ovid (including AMED, Global Health, HMIC, Medline and PsycINFO); Scopus; Web of Science; SCIE; and Science Direct. Additionally, three journals—British Journal of Social Work, Australian Social Work and Journal of Evidence Informed Social Work (previously Evidence Based Social Work)—were searched directly.

Where the search engine allowed (in every case except Science Direct, SCIE and the individual journals), three sets of “AND” criteria were applied: one for technology; one for relationship type; and one for service user type (see Table 1). Searches were made in Title, Abstract and Key Word fields where possible (as opposed to full text).

All results—citations and abstracts—were imported into Endnote: a total of 1,311. These were checked and five dated pre-2005 and one non-English language paper were removed (1,305). A further 587 duplicates were identified (the majority using the automatic duplicate identifier and the rest via a visual check of authors, year, title and journal title). About 718 abstracts were eventually selected for review.

After initial abstract reading, key word searching using Endnote, and discussion with the research team, a further set of inclusion criteria was agreed:

- Referring to the use of (any) mobile/cell/smartphone

- Referring to emotional or social support service context or referring to relationships between service user and provider or support relationships facilitated by provider

- Referring to one-to-one support/relationship

This second criteria was further refined during the abstract reading to emphasise a focus on—rather than merely a mention of—social support. This meant a large number of healthcare studies where mobile interventions which focused predominantly on adherence to treatment or management regimes, and also noted some relevance of social support, could be excluded. Three researchers read through the abstracts and selected papers according to these further inclusion criteria. Once three provisional lists (one per team member) had been assembled, these were checked for agreement. Papers with two out of three and three out of three agreements were automatically selected for full text reading; papers with one out of three agreements were further checked (including in some cases referring to the full text) by two of the team.

Twenty-one papers (1 Cochrane review, 4 doctoral theses and 16 peer-reviewed journal articles) remained after this stage. Full texts were then sought and the 15 peer-reviewed journal articles and Cochrane review were successfully obtained. In the case of the doctoral theses, one was unobtainable. Another was found to be related to a more recent peer-reviewed journal article (Barlott, Adams, Díaz, & Molina, 2015) that addressed the same study, and so this thesis was excluded from the full text read. Similarly, another thesis requested from the original author resulted in the receipt of a more recently published peer-reviewed academic journal article (Brown, Hudson, Campbell-Grossman, & Yates, 2014), and this was also used in place of the full thesis. The fourth thesis was received from the author and included in the full text read (Moon, 2013). One further paper (Walker, Koh, Wollersheim, & Liamputtong, 2015) was added when journal articles reporting pilot studies were followed up to check if full trials had since been undertaken. Twenty papers (1 Cochrane review, 1 doctoral thesis and 18 peer-reviewed journal articles) were eventually taken forward for the full text read.

The first and second author then read and charted the full texts in Microsoft Excel. The following information was recorded:

- Author, date and title

- Location of study

- Research design/methodology

- Service user group

- Description of technology/mobile intervention

- Key findings—including positive and negative findings

- Other notes

A number of complementary themes were identified across the different papers and a potential typology of different kinds of mobile phone intervention has then been suggested.

3 FINDINGS

The findings have been grouped into three complementary themes concerning:

- Intervention effects (social support, improvements in symptoms and the potential for empowerment)

- Issues of accessibility and cost to services (improved access to services for isolated and disadvantaged service users)

- Potential challenges presented by these new technologies (issues of privacy, confidentiality and possible surveillance and concerns over the unregulated development of “apps” or applications that can be used by phones)

3.1 Theme 1: Intervention effects: Social support, symptom improvement and empowerment

3.1.1 Social support

A number of papers reported positive benefits of mobile phone interventions for the therapeutic relationship between service providers and users. This included interventions where mobile phones provided two-way contact (Ben-Zeev, Kaiser, & Krzos, 2014) or contact additional to traditional contact (Johnson, Williams, & Zlotnick, 2015), as well as those where participants only received supportive SMS messages (Agyapong, Milnes, McLoughlin, & Farren, 2013; Brown et al., 2014; De Jongh, Gurol-Urganci, Vodopivec-Jamsek, Car, & Atun, 2012; Rana et al., 2015). Interventions focusing on peer support reported positive benefits (Barlott et al., 2015; Hackett, Johnson, Shaw, & McDonagh, 2005; Walker et al., 2015; Wollersheim, Koh, Walker, & Liamputtong, 2013). While there were examples in many of these studies of participants for whom the intervention was less effective, only Daker-White and Rogers (2013) reported overall negative results. In the three studies they reported on, the mobile phone interventions were automated and appeared not to be designed primarily for social support.

Pre-existing support levels were associated with intervention outcomes in two studies. Barlott et al. (2015) noted that one participant who had not met baseline criteria for social exclusion did not experience their intervention as useful. Guillory et al. (2015) noted that only participants with higher levels of existing support experienced lasting effects post-intervention.

3.1.2 Other effects

Other positive effects were reported by a number of studies. Two studies noted improvements in co-morbid mental health diagnoses and substance misuse (Agyapong et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2015). Alvarez-Jimenez et al. (2014) and Hartzler and Wetter (2014) both described studies that reported mental health symptom improvement. Guillory et al. (2015) in their study of chronic pain patients noted various improvements in symptom severity compared to baseline. However, Hartzler and Wetter (2014) reported that SMS-based peer support among diabetes patients found no positive health or support effects. This was hypothesised as being related to various logistical and culturally specific circumstances.

Mobile phone interventions were experienced as empowering or as challenging traditional power relations by a number of studies (Agyapong et al., 2013; Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2014; Nolan, Quinn, & MacCobb, 2011; Walker et al., 2015; Wollersheim et al., 2013). This was attributed to having more control over the intervention or being empowered to take up a particular service beyond the intervention. Yoo et al. (2015) noted that mobile phone messaging between adolescents and healthcare providers could enable young people to bypass parental “gatekeeping” behaviour which restricted their access to information.

Information itself was another reported benefit. While one intervention was specifically designed to provide useful information to participants (Brown et al., 2014), four other studies reported information benefits, including increased access to networks provided and enhanced by the interventions to gain helpful information (Barlott et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2015; Wollersheim et al., 2013; Yoo et al., 2015).

3.2 Theme 2: Accessibility and cost: Improving access to services for isolated and disadvantaged groups

The accessibility of mobile phone technology and different demographics of use were key points raised in several papers. Mobile phone technology was described as positive for improving access to services, particularly for those who lived in remote or inaccessible locations and/or had limited mobility (Barlott et al., 2015; Daker-White & Rogers, 2013; De Jongh et al., 2012; Hartzler & Wetter, 2014; Norris, Swartz, & Tomlinson, 2013). Barlott et al. (2015) noted the broader reach of mobile phone technologies compared with computers and broadband in low-income countries, while a number of studies highlighted the relative low cost (in developed contexts) of SMS interventions. However, cost was an accessibility issue in other contexts (Norris et al., 2013; Rana et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2015). Furthermore, impairments related to vision, cognition, mobility or dexterity were cited as potential access issues (Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; De Jongh et al., 2012; Hartzler & Wetter, 2014; McColl, Rideout, Parmar, & Abba-Aji, 2014).

Elsewhere, Alvarez-Jimenez et al. (2014) noted that participants with more severe symptoms and poorer social skills were most likely to drop out of text-based interventions. Other papers found accessibility issues including lack of relevant literacy skills and availability of interventions in local languages/dialects (Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; De Jongh et al., 2012; Hartzler & Wetter, 2014; Norris et al., 2013). In some low-income contexts, phone sharing is common practice which may affect access (Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; Moyer, 2014; Rana et al., 2015). Few of the studies in this review attempted to address these accessibility issues, except in terms of financial accessibility.

Some papers noted the usefulness of mobile phone interventions to young people as a demographic (De Jongh et al., 2012; Moon, 2013; Nolan et al., 2011) or conversely the barriers that an older demographic might face and the need for training in new technology for some users (McColl et al., 2014). Gender differences (more male than female participants) in engagement with and use of mobile phone technologies were found (Daker-White & Rogers, 2013; Nolan et al., 2011). Despite noting gender differences in their literature review and more male than female participants, Nolan et al. (2011), however, did not identify gender differences in the content of the messages analysed in their study.

3.3 Theme 3: Challenges of the new technology: Privacy, confidentiality, surveillance and lack of regulation

A number of challenges regarding the use of mobile phone technologies were identified, in particular data protection, privacy, confidentiality and risk of loss or theft (De Jongh et al., 2012; Hartzler & Wetter, 2014; Johnson et al., 2015; McColl et al., 2014; Rana et al., 2015). In situations where phones are shared, privacy was a concern (Norris et al., 2013; Rana et al., 2015). Reamer (2013, 2015) highlighted issues with regard to social workers’ use of ICT such as informed consent. Johnson et al. (2015) reported that sometimes lack of trust between service user and provider led to confidentiality concerns. The potential for misunderstandings via the use of SMS due to inaccurate typing or a lack of “verbal and non-verbal cues” was reported (De Jongh et al., 2012; Moon, 2013).

Moyer (2014) discussed surveillance by peer mentors acting as intermediaries between service user and provider. Peer mentors in this study had to negotiate between formal and informal contact with service users where formal contact was more anonymous and one way, while informal contact involved “more socially embedded” exchanges (Moyer, 2014, p. 158). However, Moyer observed a shift towards more formal methods, raising questions about how this might impact peer mentoring. Elsewhere, Johnson et al. (2015) described phones as potentially facilitating both empowerment and surveillance. It seems that different kinds of intervention present different balances between empowerment and surveillance.

Three papers noted a lack of regulation in the development of smartphone applications which meant that “apps” could be developed by unlicensed therapists or those primarily seeking financial gain (Guillory et al., 2015; McColl et al., 2014; Norris et al., 2013). Other concerns, such as using a phone while driving, being able to report misuse or abuse of mobile phone apps or the potential for dependency on receiving regular SMS support, were found (De Jongh et al., 2012; McColl et al., 2014; Norris et al., 2013; Rana et al., 2015). Ease for participants to opt in or out of an intervention (Agyapong et al., 2013) and the need for interventions to be flexible and accommodate multiple users with different abilities (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., 2014) were noted.

4 DISCUSSION: A POTENTIAL TYPOLOGY OF MOBILE PHONE INTERVENTIONS

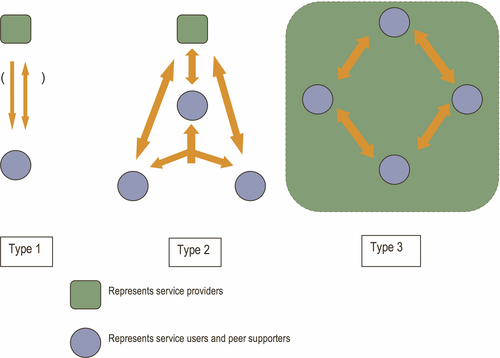

The reviewed papers explored different relationships between service providers and service users. These reflect, in part, the facilitation of particular relationships by mobile phone technologies—between service provider and service user, between service users themselves or a mix of the two—as well as challenging the professional/client binary in the context of trained peer support. Here we suggest a typology of mobile phone interventions, based on the relationship types they facilitate. These different intervention styles facilitate have various implications for changing relationships between service providers and service users, as well as potentially different risks and benefits for those involved.

4.1 Type 1: Unidirectional and bidirectional interventions

By far the most common, featuring in 14 of the 21 papers, were interventions categorised as unidirectional or bidirectional. Unidirectional interventions were those where automated SMS messages (with supportive/educative themes) were sent from the service provider to the service user, with no response facility arranged. Seven papers discussed this type of intervention (Agyapong et al., 2013; Alvarez-Jimenez et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2014; Chen, Mishara, & Liu, 2010; Daker-White & Rogers, 2013; Guillory et al., 2015; Rana et al., 2015). While many such interventions were excluded from this review, these were included because social support was either intended or experienced. Bidirectional interventions (between service provider and service user but with both parties having the ability to respond or initiate contact) were described in five papers (Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; Moon, 2013; Nolan et al., 2011; Norris et al., 2013; Yoo et al., 2015), and an additional two mentioned both types (De Jongh et al., 2012; Hartzler & Wetter, 2014).

Of these bidirectional papers, four (Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; Moon, 2013; Nolan et al., 2011; Yoo et al., 2015) considered the use of mobile phone technologies as enhancements to therapeutic relationships. Moon (2013) and Nolan et al. (2011) explored text messaging between therapist and mental health service user beyond traditional face-to-face interactions. Moon (2013) focused on therapists’ perception of the use of text messaging (convenient and client-centred and also raising challenges of professional boundaries), while Nolan et al. (2011) investigated content of messages and noted practical as well as relational use (arranging appointments as well as discussing therapeutic issues). Yoo et al. (2015) considered the content of messages between asthma patients and their nurse managers. Messages were predominantly task-focused but a significant number also related to socio-emotional issues. Ben-Zeev et al.'s (2014) research trialled a new intervention, called “hovering”, which monitored and supported dual diagnosis (mental health problems and substance use) patients via daily, two-way text messaging between them and a trained “mobile interventionist” who also reported on their progress to the community team involved in the conventional treatment of the patient.

4.2 Type 2: Bidirectional and multidirectional interventions

Three papers considered interventions involving bidirectional and multidirectional relationships—between service users themselves and/or trained peer supporters as well as between service users and providers (Barlott et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2015; Moyer, 2014; Yoo, 2014). Each reported innovative interventions in very different contexts. Barlott et al. (2015) used an SMS messaging “hub” to facilitate two-way communication between caregivers of people with disabilities living in a low-income, mountainside community and between caregivers and a community co-ordination team. Johnson et al. (2015) provided women “with co-morbid substance use and depressive disorders” (p. 330), who were leaving prison and returning to their communities, restricted mobile phones with pre-paid minutes to maintain contact with prison counsellors as well as positive local networks (e.g. sober friends and family). Moyer (2014) reported on a peer mentor programme in a hospital-based HIV treatment centre which used “expert clients” to support newly diagnosed clients, both in person and by mobile phone. Yoo (2014) described a study where participants with alcohol use disorders were given a smartphone with an app facilitating forum communication with peers as well as direct links to professional service providers.

4.3 Type 3: Multidirectional interventions

Four papers focused specifically on interventions developing multidirectional relationships (between service users themselves and/or trained peer supporters) within services facilitating those relationships (Hackett et al., 2005; McColl et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2015; Wollersheim et al., 2013). McColl et al. (2014) reviewed the literature relating to peer support mobile phone applications for people experiencing mental distress, while Hackett et al. (2005) in the context of an intervention for young people with chronic rheumatic diseases noted that one benefit was the development of peer relationships maintained by text messaging. Wollersheim et al.'s (2013) pilot and Walker et al.'s (2015) subsequent study reported an intervention providing peer support training and mobile phones with free calls to refugee women who had migrated to Australia.

The different intervention types have implications for power relations between service providers and users. While some unidirectional (Type 1) interventions were experienced as empowering by service users, this model also most closely resembles a traditional professional–client hierarchy, raising questions about its emancipatory potential (Rivest & Moreau, 2015). While bidirectional (Type 1) interventions also carry this risk (particularly those set in more medicalised contexts), they also have the potential to realign (at least partially) power relations between service provider and user.

Although interventions of types 2 and 3—involving multidirectional relationships—were in the minority among the papers included, they may offer the most potential for communications and interventions that resist current hierarchical and linear conventionalities of service provision. In these interventions, communication may be enriched and empowerment increased in comparison to type 1 interventions and they therefore represent a potentially transformative approach to using mobile phone technologies with service users by facilitating a collective development of networks and social capital. A dilemma for service providers is that these forms of intervention make it much harder for them to control the communications that occur.

Types 2 and 3 interventions have potential for developing service users’ social capital. While only one paper (Wollersheim et al., 2013) specifically used the concept of social capital, a similar approach could be identified in all seven papers covering these intervention types: one fitting the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2001) definition of social capital: “networks together with shared norms, values and understandings that facilitate co-operation within or among groups.” This is also the definition underlying the UK's official measurement of social capital (Office for National Statistics, 2014) and draws on the work of a number of prominent social capital theorists including Putnam (1995, 2001). These approaches tend to be used to highlight the positive aspects of social capital—for example the sense of community derived from robust social networks and shared values. However, other understandings of social capital focus on its role in reproducing, and being produced by, social inequalities (e.g. Bourdieu, 1986). While studies such as Wollersheim et al. (2013) and Walker et al. (2015) look at increasing social capital in the sense of developing broad social networks and increasing community cohesion, the more critical perspective of scholars such as Bourdieu should not be overlooked (Figure 1).

Several papers note the potential for mobile phones to enhance social networks for people isolated by geography, disability or other circumstances. Walker et al. (2015) described their intervention as providing a welfare service tailored to the needs of the refugee population, based around the provision of mobile phones and free calls, highlighting the unique contribution mobile phone technologies can make to communication networks offering support. These studies highlight the potential of interventions which unlock potential and increase social capital among service users directly—reducing the service provider's direct influence on communication. This highlights the potentially transformative potential of mobile phone technology in service delivery and its significance for resource-limited contexts.

A number of important implications concerning risks and benefits of mobile communication emerged from the papers. Several note the concerns of service providers—risks of crossing work/private boundaries, out of hours communications reporting self-harm or suicidal thoughts—which have made some reluctant to engage with mobile phone communication and highlighted the need for staff training and new policies. Ben-Zeev et al. (2014) noted the importance of service users receiving training in using mobile phones in these contexts and the need for accountability and confidentiality. Issues such as saving peoples’ contacts and texts will need careful exploration.

An issue raised in several of the cited papers, and by Lawton (2014) in her original study, is that professionals and volunteer peer mentors/befrienders may be viewed differently and may have different training needs. Befrienders may be seen as more approachable, flexible and non-judgemental by service users, raising implications about how boundaries are negotiated and the potential for tension and conflict between professionals and peer mentors. The way mobile phones blur or collapse boundaries between work and private spaces has already been noted.

A question raised in several of the cited papers and by Lawton (2014) was whether calls and texts serve different purposes with asynchronous communications allowing people to say things they may not feel able to otherwise communicate.

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS

This scoping review has covered a number of topics and raised significant questions and areas for future research. A lack of any really definitive literature beyond that closely associated with health outcomes means much of the evidence is not yet robust. The difficulty in distinguishing the specific effect of the mobile phone intervention (as opposed to other online interventions) is another issue but several papers pointed to the rich possibilities offered by easily portable phones.

The need for appropriate training of service providers regarding the delivery of mobile phone interventions appears significant, both in terms of new technology and in relation to expectations of confidentiality and data protection. The reluctance of some service providers to engage with new technologies was noted in some of the studies and has also been discussed in the wider literature relating to technology and social work practice. The lack of concrete guidance, even where professional standards do exist, is a key concern (Mattison, 2012). Reamer's (2015) consideration of social workers’ use of ICT addressed similar issues, including blurring of boundaries, dual relationships and conflicts of interest, and the need for practitioners to develop specific protocols for these issues. However, the risks of this leading to potentially harmful practices are noted by Mattison (2012). Chan (2015) draws attention to work that indicates practitioners relying largely on their own discretion. This means there may be a risk of at best inconsistent, and at worst unsafe and potentially harmful, practice where appropriate guidance is not in place.

This is particularly relevant given the changes that mobile phone technologies inevitably bring to a service provider–service user relationship. Wajcman et al. (2008) drew attention at the start of this review to mobile phones reducing or removing boundaries between the personal and professional. While none of the studies in this review explicitly investigated changing relationships, concern around service user/provider boundaries was a key issue for practitioners in a number of the studies (e.g. Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; Moon, 2013). Professionals and peer mentors may differ in their roles but may have similar training needs in many respects. Commonalities would include issues of staff exploitation and burnout, of boundaries and confidentiality, of the implications of surveillance of service users and the unequal power relationships between professionals and peer mentors.

There is growing evidence that many service users wish to use these technologies in the context of service provision (see for example Dodsworth et al., 2013; Mattison, 2012) and may themselves also need training. Greater accessibility for remotely located service users or those with limited mobility are both potential benefits of mobile phone interventions, but accessibility of services for those who struggle to access mobile phone technology (due to cost, literacy or impairment) also needs to be taken into account.

The role of mobile phones in developing social networks and increasing social capital seems particularly significant. There are similarities between some of the findings of these studies and other research examining mobile phones as “network capital” in everyday life (Rettie, 2008). Rettie follows Larsen et al.'s definition of network capital as ‘access to communication technologies, affordable and well-connected transport, appropriate meeting places and caring significant others that offer their company and hospitality’ (Larsen et al., 2006, in Rettie, 2008, p. 292). Some have drawn on Castell's network society thesis to describe the role of social workers in modern society (Baker, Warburton, Hodgkin, & Pascal, 2014; Smith, 2012) as “network-makers,” for example assisting service users to change and develop their networks and multidirectional mobile phone use may play an increasingly important role here.

In the UK, current government-led austerity measures mean finding efficiencies and reducing costs is a necessity for many service providers, demanding a need to explore the cost-effectiveness of interventions. Several papers emphasise the importance of face-to-face contact before or alongside interventions involving bidirectional interventions, suggesting that mobile phone interventions enhance more traditional service user relationships rather than replacing them in a bid to reduce costs (Ben-Zeev et al., 2014; Moon, 2013; Nolan et al., 2011; Yoo et al., 2015).

In contrast, some interventions were potentially designed to replace face-to-face services (e.g. Brown et al., 2014; McColl et al., 2014), while others aimed to offer a new service where none had previously existed (e.g. Barlott et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2010; Rana et al., 2015). The relatively low cost and wide reach of mobile phone interventions may thus be a positive first step for developing services in some contexts. Further potential for cost-efficiency and continued service quality is suggested by being able to offer alternative service provision in interventions involving bidirectionality, such as the “hovering” described by Ben-Zeev et al. (2014). Such potential is also suggested where participants experienced social support from unidirectional interventions (Agyapong et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2014; De Jongh et al., 2012; Rana et al., 2015). The work undertaken by Walker et al. (2015) and Wollersheim et al. (2013) suggests potential for cost-effective service provision by developing the self-efficacy and social capital of service users and training them to support each other may reduce reliance on other services. However, none of these studies were undertaken in the UK context. The lack of UK studies—and the way that phone use is socially constructed—means further UK-specific research is particularly needed to test the applicability of these types of interventions to British communities.

We suggest that the typology of mobile phone interventions outlined here may be a very useful model for future research to draw on in exploring the advantages, limitations and dilemmas of using mobile phone technology in social care settings to support and empower isolated and vulnerable service users. This remains an under-researched area and the development of a robust knowledge base is essential as mobile phone technologies come increasingly to shape and transform the ways we live our personal and professional lives.