Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review

Abstract

Loneliness and social isolation are major problems for older adults. Interventions and activities aimed at reducing social isolation and loneliness are widely advocated as a solution to this growing problem. The aim of this study was to conduct an integrative review to identify the range and scope of interventions that target social isolation and loneliness among older people, to gain insight into why interventions are successful and to determine the effectiveness of those interventions. Six electronic databases were searched from 2003 until January 2016 for literature relating to interventions with a primary or secondary outcome of reducing or preventing social isolation and/or loneliness among older people. Data evaluation followed Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre guidelines and data analysis was conducted using a descriptive thematic method for synthesising data. The review identified 38 studies. A range of interventions were described which relied on differing mechanisms for reducing social isolation and loneliness. The majority of interventions reported some success in reducing social isolation and loneliness, but the quality of evidence was generally weak. Factors which were associated with the most effective interventions included adaptability, a community development approach, and productive engagement. A wide range of interventions have been developed to tackle social isolation and loneliness among older people. However, the quality of the evidence base is weak and further research is required to provide more robust data on the effectiveness of interventions. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to further develop theoretical understandings of how successful interventions mediate social isolation and loneliness.

What is known about this topic

- Loneliness and social isolation are major health problems for older adults.

- A growing range of interventions have been developed to tackle social isolation and loneliness.

- Little is known about the range and scope of effective interventions, and what aspects of interventions contribute to their success.

What this paper adds

- A range of interventions were described which relied on differing mechanism for reducing social isolation and loneliness.

- Common features of successful interventions included adaptability, a community development approach and productive engagement.

- Contrary to previous review findings, our review did not find group-based activities to be more effective than one-to-one or solitary activities.

Background

Loneliness and social isolation are major problems for older adults and are associated with adverse mental and physical health consequences (Luanaigh & Lawlor 2008). A recent review identified a wide range of health outcomes associated with loneliness and social isolation including depression, cardiovascular disease, quality of life, general health, biological markers of health, cognitive function and mortality (Courtin & Knapp 2015). Chronically lonely older people also report less exercise, more tobacco use, a greater number of chronic illnesses, higher depression scores and greater average number of nursing home stays than those who are not lonely (Theeke 2010). The mechanisms by which social isolation and loneliness impact on health are not well understood, but are thought to include influences on health behaviours, sleep, vital exhaustion and social connectedness (Courtin & Knapp 2015). Older people are particularly vulnerable to loneliness and social isolation due to deteriorating physical health, the death of spouses and partners, being more likely to live alone and having fewer confiding relationships (Victor & Bowling 2012).

The terms social isolation and loneliness are interrelated but describe different concepts. Social isolation refers to the objective absence or paucity of contacts and interactions between a person and a social network (Gardner et al. 1999), whereas loneliness refers to a subjective feeling state of being alone, separated or apart from others, and has been conceptualised as an imbalance between desired social contacts and actual social contacts (Weiss 1973, Ernst & Cacioppo 1999). Despite these variable definitions, evidence suggests significant overlap between social isolation and loneliness (Golden et al. 2009), and the terms are often used interchangeably. Crucially, both concepts result in negative self-assessment of health and well-being in older people (Golden et al. 2009).

National and international health and social care policies and campaigns are increasingly recognising the importance of tackling social isolation and loneliness among older people. For example, in the UK The Campaign to End Loneliness was established in 2011 as a network of national, regional and local organisations working together to ensure that loneliness is acted upon as a public health priority at national and local levels (Campaign to End Loneliness 2011). Similarly, the New Zealand government has committed to a vision of positive ageing principles which promote community participation and prevent social isolation (MSD 2001). Interventions and activities aimed at alleviating social isolation and loneliness are central to such policies and initiatives, yet little is known about the range and scope of available interventions, their effectiveness, and factors which contribute to their success (Cattan et al. 2005).

A number of systematic reviews of quantitative outcome studies have been conducted over recent years, which have attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of social isolation and loneliness interventions for older people (Cattan & White 1998, Findlay 2003, Cattan et al. 2005, Dickens et al. 2011, Hagan et al. 2014, Cohen-Mansfield & Perach 2015). However, thus far, they have been unable to provide conclusive evidence, and findings are often contradictory. For example, a 2005 systematic review reported that the majority of effective interventions were group activities, and the majority of ineffective interventions provided one-to-one social support (Cattan et al. 2005). In contradiction, in their 2015 review, Cohen-Mansfield and Perach (2015) noted that group interventions were less often evaluated as effective compared with one-on-one interventions. Important to note is that reviews to date have focused solely on quantitative outcome studies, and have failed to take account of other forms of evidence. Concerns are increasingly being raised that reviews of quantitative evidence fail to adequately capture depth and breadth of research activity, and varied perspectives on a phenomena (Torraco 2005, Whittemore & Knafl 2005). This concern is reflected in recent guidance which calls for greater integration of qualitative research methods in interventional designs, in order to better understand implementation, receipt, and setting of interventions and interpretation of outcomes (Oakley et al. 2006, Lewin et al. 2009). Finally, despite the existence of a number of reviews in this area, there is still a widespread recognition of a need for further research into ‘what works in tackling loneliness’ (Campaign to End Loneliness 2011). Hence, we sought to update the evidence base by conducting an integrative review of literature drawing evidence from diverse methodologies, to provide a more complete overview of the range and scope of interventions, gain insight into why interventions are successful and explore effectiveness where feasible.

Methods

The aim of this study was to conduct an integrative review of literature on interventions that target social isolation and/or loneliness in older people. The integrative review method is an approach that allows for the inclusion of diverse methodologies, and has the potential to allow for diverse primary research methods to inform evidence-based practice (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). This method was chosen so that multiple methods could contribute to the generation of new insights. For example, quantitative research could provide insights into effectiveness and qualitative research could provide insights into the experiential impact of interventions and mechanisms of action of interventions.

A systematic search strategy was devised by the authors with input from a specialist subject librarian. The strategy included the following MeSH headings and keywords relevant to the research aim: lonel*, social isolat*, prevent*, reduc*, minimi*, less*. While social isolation and loneliness are recognised as distinct concepts, the terms are interrelated and are often used interchangeably. Understanding of intervention effects can be enhanced through the inclusion of studies reporting on outcomes known to be associated with both social isolation and loneliness (Dickens et al. 2011), therefore both terms were included as search terms. This approach is consistent with several previous reviews (Cattan & White 1998, Cattan et al. 2005, Dickens et al. 2011). Six electronic databases (PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo, ScienceDirect, EMBASE) were searched from 2003 until January 2016. The earliest of the previous reviews included literature up to 2003 (Findlay 2003), therefore only literature published after this date was included in our review. Reference lists of included studies were also hand-searched. Grey literature searches were undertaken drawing on a range of materials published by organisations selected on the basis of their relevance to the research topic (e.g. Age UK, HelpAge International). The journal Ageing and Society was also hand-searched as the most frequently cited journal in this area.

Following removal of duplicates, G.G. screened titles and abstracts of all returned publications to identify those which met the study inclusion criteria. Study inclusion criteria are listed in Box 1. While the review was limited to primary empirical research, in keeping with integrative review methods, all methodologies were included. As the term ‘older adult’ is inconsistently defined in the literature, the term was determined by the criteria set out in the identified studies. Full texts of all included articles, and any where there was disagreement, were further independently screened by G.G. and C.G. Where there was lack of agreement, M.G. acted as a third independent reviewer and decisions were made by consensus. Details of included studies were extracted into predefined tables.

Box 1. Inclusion criteria

| Literature relating to interventions with a primary or secondary outcome of reducing or preventing social isolation and/or loneliness |

| Literature relating to older adults |

| Empirical research articles reporting primary research, published in full, including all research methodologies (but excluding reviews) |

| English language articles |

| Published since 2003 |

- Methodological quality and the trustworthiness of the results.

- Methodological relevance defined as the appropriateness of the study design for answering the review question.

- Topic relevance defined as the appropriateness of the topic in relation to the review question.

Methodological quality was evaluated by examining the quality of each study using the hierarchy of evidence as a guide (Evans 2003), and its execution thereof. Methodological relevance was evaluated by assessing the appropriateness of each study's design for addressing its research question. Topic relevance assessed how well matched each study was to the focus of our review in terms of topic (Gough et al. 2012). A score out of three was given for each domain (1 = poor, 2 = acceptable, 3 = good) and a combined total score out of nine was generated, any study with a score of ≤3 was excluded due to insufficient quality.

Strategies for data analysis developed for mixed method or qualitative reviews are particularly applicable to the integrative review method as they allow for iterative comparisons across data sources. As such, data analysis was conducted using a descriptive thematic method for synthesising data (Health Development Agency 2004). This method was chosen as it allows clear identification of prominent themes and provides an organised and structured way of dealing with data from diverse methodologies. Studies were classified by intervention category and a data-driven approach was used to identify other major or recurrent themes relating to the research aim; a process of constant comparison was used to compare coded categories and enhance rigour (Glaser & Strauss 1967, Health Development Agency 2004).

Results

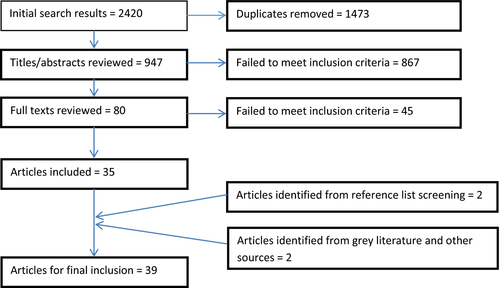

Search results are summarised in the adapted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart in Figure 1. A total of 2420 studies were identified, of which 39 met our inclusion criteria (see supporting material Table S1). Of these, 6 were randomised controlled trials (RCT), 21 were other quantitative designs, 10 were qualitative studies and 2 were mixed method studies.

Quality of evidence

All studies achieved a score ≥3 on quality appraisal and therefore no studies were excluded on the basis of quality. However, overall the included studies showed inconsistent levels of quality and consistency. Only three of the 39 included studies merited the top score of 9 on quality appraisal with studies assessing ‘psychological therapies’ generally of the highest quality (see Table S1 supporting material for further details on study design and quality). The inconsistent quality of the included articles indicates the findings from this review should be accepted with caution and generalisability may not be appropriate. Quality appraisal scores are noted in Box 2. Included studies provided variable definitions of social isolation and loneliness. The measures used to evaluate loneliness and social isolation outcomes showed some consistency. The majority of quantitative studies used validated tools, commonly the UCLA loneliness scale (or modified version thereof) (Russell et al. 1980), the De Jong Gierveld scale (de Jong Gierveld & Kamphuis 1985) or the Lubben Social Network scale (Lubben 1998). Some studies used single-item indicators which may undermine the validity of results; however, research has indicated that single-item measures can correlate strongly with more complex measures (Victor et al. 2005). Inconsistencies in definition and measurement across the 39 studies mean the practice and policy relevance of findings may be limited.

Box 2. Common characteristics of interventions which demonstrate a positive impact on social isolation and/or loneliness

| Adaptability | National interventions funded by governments or other larger organisations may have set criteria for implementation and execution of an intervention; however, a frequently observed criticism was a lack of being able to adapt interventions for the specific needs of a local population (Wylie 2012). |

| Project co-ordinators from a national befriending service commented that more local control was need to respond to the community and to enhance the service (Kime et al. 2012). | |

| Local control conducive to meaningful friendship, especially when attendees control the activities and the activities are relevant to their interests (Hemingway & Jack 2013). | |

| The need for adaptability may be driven by differences in population demographics. | |

| Flexibility can also mean services and support can meet the individual needs of older people (Cattan & Ingold 2003). | |

| Community development approach | Older people wish to have an opportunity to be involved in project development and delivery, and to be supported to contribute to such activities (Cattan & Ingold 2003). |

| Interventions that involved users in the design and implementation were more successful (Bartlett et al. 2013). | |

| Interventions that aimed to preserve service user autonomy by allowing participants to decide the activities to be undertaken also seemed to be more effective (Hemingway & Jack 2013). | |

| Activities were more likely to be effective if older people were involved in the planning, developing and execution of activities (Wylie 2012). | |

| Older people sometimes found the activities organised by others patronising (Pettigrew & Roberts 2008). | |

| Building partnerships may also lead to interventions still being implemented after professional services have withdrawn engagement (Cant & Taket 2005, Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2007). | |

| Productive engagement | Interventions focussing on productive engagement seemed to be more effective than those which involved passive activities (Pettigrew & Roberts 2008). |

| Productive activities include group interventions focussed on socialisation or creating opportunities for socialisation and forming new social networks. | |

| In addition, productive engagement may also include solitary activities. | |

| ‘Doing’ things accumulates more social contacts than watching or listening to things. Doing things refers to productivity and involves action and creativeness and is often directed towards a (common) goal (Toepoel 2013). | |

| Activities that presented a challenge were suggested as being most appropriate (Howat et al. 2004). | |

| Adult day groups supporting productive activities led to participants reporting lower levels of loneliness through keeping occupied (Tse & Howie 2005) |

Categories of intervention

There was significant heterogeneity in the interventions identified and the majority comprised multiple and interacting components. Thematic analysis identified six categories of intervention based on their purpose, their mechanisms of action and their intended outcomes (see supporting material Table S1). The categories were social facilitation interventions, psychological therapies, health and social care provision, animal interventions, befriending interventions and leisure/skill development. While many interventions utilised mechanisms from more than one category, the majority had a primary focus in one of these six areas.

Social facilitation interventions

This was the most prominent category which described interventions with the primary purpose of facilitating social interaction with peers, or others who may be lonely. Social facilitation interventions generally presumed a degree of reciprocity, and strived to provide mutual benefit to all participants involved. Many of these interventions involved group-based activities, for example charity-funded friendship clubs (Hemingway & Jack 2013), shared interest topic groups (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2007), day care centres (Iecovich & Biderman 2012) and friendship enrichment programmes (Martina & Stevens 2006, Stevens et al. 2006, Alaviani et al. 2015). One intervention focused on the specific role of Irish cultural identity in social facilitation (Cant & Taket 2005). Two interventions proposed innovative technology-based solutions to aiding socialisation using videoconferencing and social networking (Ballantyne et al. 2010, Tsai et al. 2010).

All but two of the social facilitation interventions reported some success in reducing social isolation or loneliness (Cant & Taket 2005, Tse & Howie 2005, Stevens et al. 2006, Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2007, Ballantyne et al. 2010, Tsai et al. 2010, Hemingway & Jack 2013, Alaviani et al. 2015). For example, Tsai et al. (2010) evaluated a videoconference programme which aimed to facilitate contact between an older person and their family. They reported lower levels of loneliness (as measured by the UCLA scale) among those using the videoconference. Qualitative studies were useful in identifying factors which supported the success of interventions and included a supportive environment (Ballantyne et al. 2010), a sense of companionship and keeping occupied (Tse & Howie 2005), and creating a sense of belonging (Cant & Taket 2005). Two studies, evaluating day care centres for frail older people and a friendship enrichment programme, were unable to demonstrate any impact on loneliness (Martina & Stevens 2006, Iecovich & Biderman 2012).

Psychological therapies

This category of intervention utilised recognised therapeutic approaches delivered by trained therapists or health professionals. The review identified this category of intervention as having the most robust evaluation to date. Humour therapy (Tse et al. 2010), mindfulness and stress reduction (Creswell et al. 2012), reminiscence group therapy (Liu et al. 2007), and cognitive and social support interventions (Saito et al. 2012) were all successful in significantly reducing loneliness and had a positive impact on a range of other outcomes including social support, happiness and life satisfaction. A common feature of these interventions was that they all involved facilitated group-based activities. However, as most involved a therapeutic approach in addition to some sort of group interaction, the individual factors contributing to the success of the interventions were not always clear. Two studies failed to show a significant reduction on social isolation or loneliness. A quasi-experimental evaluation of cognitive enhancement therapy did not demonstrate a significant reduction in loneliness, but did note a significant increase in loneliness in the control group over time, perhaps indicating a maintenance effect of the intervention (Winningham & Pike 2007). An RCT of a psychological group rehabilitation intervention also failed to demonstrate a reduction in loneliness, but did show an increased number of friendships in the intervention group (Routasalo et al. 2009).

Health and social care provision

This category described interventions involving health, allied health and/or social care professionals supporting older people. These interventions were characterised by the involvement of health and social care professionals and enrolment in a formal programme of care, either in a nursing home (Bergman-Evans 2004, Loek et al. 2012) or community setting (Bartsch et al. 2013, Nicholson & Shellman 2013, Ollonqvist et al. 2008). A diverse range of models were identified including a community network of trained gatekeepers (Bartsch & Rogers 2010) and geriatric rehabilitation run by clinical and allied health staff (Ollonqvist et al. 2008). Nicholson and Shellman (2013) evaluated the CARELINK programme, a university–community partnership, where nursing students visited older people to aid socialisation. A post-test only study revealed that those receiving the intervention were 12 times less likely to report social isolation than those in a control group. Only one study in this category failed to demonstrate a significant reduction in either loneliness or social isolation. Bergman-Evans (2004) undertook a quasi-experimental evaluation of the Eden alternative model, a residential care model aiming to create a more ‘human habitat’ in residential care. While they were unable to demonstrate any significant reduction in loneliness as measured by the UCLA scale, they did report significantly lower levels of boredom and helplessness in the intervention group.

Animal interventions

Three studies described and evaluated canine or feline animal interventions, which focussed mainly on animal-assisted therapy. In a cross-sectional study, Krause-Parello (2012) interviewed pet-owning women, and concluded that pet attachment could alleviate loneliness by acting as a coping mechanism, possibly by providing social support and companionship. An RCT by Banks and Banks (2005) attempted to determine whether it is the animal–human connection or a subsequent human–human connection that is responsible for a reduction in loneliness. They concluded that animal-assisted therapy was more effective in the individual setting, and therefore the human–animal interaction is most responsible for reducing loneliness. Banks et al. (2008) compared a living dog with a robotic dog and found that while a higher level of attachment was found with the living animal, both groups showed a significant reduction in loneliness and there was no significant difference in loneliness between groups.

Befriending interventions

Befriending interventions are defined as a form of social facilitation with the aim of formulating new friendships. Befriending interventions were usually one-to-one and often involved volunteers. They differ from social facilitation interventions in that the primary aim is to support the lonely individual, rather than to promote a mutually beneficial relationship (although this may be an important secondary consequence). Examples included a Senior Companion Programme (Butler 2006) and the ‘Call in Time’ programme (Cattan et al. 2011, Kime et al. 2012), a national pilot of telephone befriending projects across the UK. A mixed methods evaluation found that telephone projects were successful in alleviating loneliness through making life worth living, generating a sense of belonging and ‘knowing there's a friend out there’ (Cattan et al. 2011). However, qualitative findings from befriending projects also identified a range of challenges to be overcome including volunteer recruitment, local rather than national control of projects, and promotion and publicity issues (Kime et al. 2012).

Leisure/skill development interventions

A final category of intervention focused on leisure activities and/or skill development. Activities were varied and included gardening programmes, computer/Internet use, voluntary work, holidays and sports (Brown et al. 2004, Pettigrew & Roberts 2008, Tse 2010, Toepoel 2013, Heo et al. 2015). Solitary computer-based interventions appeared the most effective and well evaluated. A 3-week computer training course and a computer/Internet loan scheme were both effective in reducing some aspects of loneliness (Fokkema & Knipscheer 2007, Blazun et al. 2012). Higher use of the Internet was also found to be a predictor of higher levels of social support and decreased loneliness (Heo et al. 2015). Two well-designed studies evaluated indoor gardening programmes for nursing home residents (Brown et al. 2004, Tse 2010). However, findings were mixed, with one study reporting a significant effect on loneliness (Tse 2010) and the other reporting no effect (Brown et al. 2004). Evidence from a qualitative study was useful for identifying how leisure activities reduced loneliness, for example by maintaining social contacts, spending time constructively and having interaction with others (Pettigrew & Roberts 2008). Toepoel (2013) distinguished between productive activities which were associated with a reduction in loneliness (e.g. reading or engaging in hobbies) and passive consumptive activities which were not (such as watching TV or listening to radio).

Factors contributing to the success of interventions

Most interventions were complex and many relied on more than one mechanism for reducing social isolation and loneliness; therefore, it was often unclear which specific aspects of an intervention contributed most strongly to its success. For example, mindfulness-based stress reduction was found to significantly decrease loneliness (Creswell et al. 2012), but as this intervention was delivered in a group setting, it was not possible to assess the unique contribution of the mindfulness element as opposed to the group interaction element. Qualitative studies were particularly useful for understanding the mechanisms underlying successful interventions due to the ability of qualitative data to provide a more nuanced understanding of the interacting elements of interventions and their contexts. Three key common characteristics of effective interventions were identified and are presented in Box 2. Adaptability of an intervention to a local context was seen as key for ensuring its success, particularly where interventions have been implemented by national organisations (Cattan & Ingold 2003, Hemingway & Jack 2013, Kime et al. 2012, Wylie 2012). A community development approach, where service users are involved in the design and implementation of interventions, was often associated with more successful interventions (Cattan & Ingold 2003, Findlay 2003, Cattan et al. 2005, Pettigrew & Roberts 2008, Wylie 2012, Bartlett et al. 2013, Hemingway & Jack 2013). Finally, activities or interventions which supported productive engagement seemed to be more successful in alleviating social isolation than those involving passive activities or those with no explicit goal or purpose (Howat et al. 2004, Pettigrew & Roberts 2008, Toepoel 2013). While it would have been useful to explore whether differences were apparent between social isolation and loneliness in response to different interventions, unfortunately the quality of data was insufficient to support such analyses. It should also be noted that as the factors contributing to the success of interventions were largely derived from qualitative research, generalisability may not be appropriate and these findings should be accepted with caution.

Discussion

This study is the first of its kind to review empirical literature from diverse methodologies on interventions to reduce loneliness and social isolation in older people. The findings identified a wide range of interventions developed to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people. Significant diversity and heterogeneity were evident in intervention design and implementation, with evidence suggesting the scope and purpose of interventions varies widely. While study quality was variable, studies reporting evaluations of interventions indicated that the majority of activities are at least moderately successful in reducing social isolation and/or loneliness. Our review extends the findings from previous reviews (Cattan et al. 2005, Dickens et al. 2011, Findlay 2003, Hagan et al. 2014); however, the use of an integrative methodology provides some interesting additional insights into this growing area of research. The inclusion of diverse methodologies has allowed us to provide a more complete picture of the range and scope of interventions available, and importantly to gain insight into the factors which influence an interventions success.

Interventions in our review were categorised according to the mechanisms by which they attempted to target social isolation and loneliness. This categorisation is important when faced with growing diversity in intervention types and is a necessary pre-requisite to identifying which elements of interventions influence their effectiveness. A number of theories have been proposed to explain the cause of loneliness (e.g. the existential, the cognitive, the psychodynamic and the interactionist) (Donaldson & Watson 1996). While there is no theoretical consensus regarding cause, these different theoretical perspectives illustrate the varying ways in which the study of loneliness has been approached (Victor et al. 2000). Similarly, the notion of social isolation is one that has been understood and defined in a number of different ways. Approaches to measuring social isolation vary but often involve recording levels of social contact, enumerating social participation and quantifying social networks. The nature of a person's social network has been identified as key to the level of social isolation that they experience (Victor et al. 2000). Theoretical perspectives on the concepts of loneliness and social isolation continue to develop and advance. Theoretical understandings of the way in which interventions mediate social isolation and loneliness also require further research attention to better understand the processes involved in implementing a successful intervention.

Interestingly, and in contrast to findings from two previous reviews (Cattan et al. 2005, Dickens et al. 2011), our study did not report group interventions as being more effective than solitary or one-to-one interventions. Our review found that solitary pet interventions (Banks & Banks 2005, Banks et al. 2008, Krause-Parello 2012) and solitary interventions involving technology such as videoconference and computer/Internet use (Tsai et al. 2010, Blazun et al. 2012) were successful in reducing the experience of loneliness. Furthermore, one study using an RCT design to evaluate animal-assisted therapy reported that the therapy was more effective in the individual rather than the group setting (Banks & Banks 2005). These findings suggest that contrary to the majority of previous research evidence, effective interventions are not restricted to those offered in group settings. Indeed, qualitative data from this review indicate that productive engagement activities, which may be solitary, are a feature of many successful interventions. These findings are significant when considering the growing number of older people who are housebound and unable to easily participate in group activities. Housebound older adults are known to be at greater risk of loneliness and social isolation and health and social care problems when compared with the general population (Qiu et al. 2010, Wenger & Burholt 2013). Innovative interventions promoting solitary activities may offer solutions for hard to reach groups of older adults such as these. While solitary activities may also appear attractive from the perspective of policy makers due to their perceived low cost, it should be noted that solitary interventions in this review are well-resourced activities which require financial investment (e.g. purchase of pet, feeding costs, cost of computer hardware and Internet). Many of these activities, while undertaken alone, also actively involve others (e.g. a pet, or an animal-visiting programme, a family to contact by Skype, or an online community) and this should be considered when planning interventions.

The use of an integrative review methodology incorporating literature with diverse methods including qualitative studies and mixed method designs has allowed for a broader and more comprehensive understanding of social isolation and loneliness interventions (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). This has enabled some novel insights into the factors which contribute to the success of such interventions, many of which emerged through qualitative enquiry. Adaptability to a local context was seen to be important in influencing the effectiveness and success of interventions. While many interventions may be developed and funded by national organisations, some local control is necessary in order to respond to local contextual factors. The need for adaptability is particularly important in the context of increasing diversity in population demographics internationally (Office for National Statistics 2011). A community development approach, where interventions are designed and implemented with input from service users, was also noted as an important feature and has previously been associated with successful social isolation and loneliness interventions (Joseph Rowntree Foundation 1998, Findlay 2003, Cattan et al. 2005). The service user or public and patient involvement movement has gained momentum over recent years, particularly in areas such as health service development and research design. The main reasons for public involvement in research are political mandate and the pursuit of ‘better’ research (Oliver et al. 2008). However, our findings suggest that this approach may also have the benefit of developing interventions which better meet the needs of the people they are intended to support. Finally, productive engagement activities may be associated with better outcomes than passive activities. This finding is in line with the review by Dickens et al. (2011) which reported participatory interventions were most likely to be beneficial. This finding may be particularly useful when designing non-group or solitary activities, and may help inform the design of solitary interventions.

Limitations

While care was taken to ensure the search strategy returned the most inclusive result, it is possible that some studies may not have been indexed or may for other reason be missing from the data. As the review employed an integrative review methodology, it was not the intention to combine results statistically; however, as a result our findings on effectiveness should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

A wide range of interventions have been developed to tackle social isolation and loneliness among older people. The majority of interventions reported some success in reducing social isolation and loneliness, but there was significant heterogeneity between interventions. Common features of successful interventions include adaptability, community participation and activities involving productive engagement. However, it is important to note that our conclusions are based on combined evidence from studies using a range of methods, and are not based on meta-analysis. Therefore, conclusions regarding effectiveness cannot be confirmed statistically. Further research is now required to enhance theoretical understandings of how successful interventions mediate social isolation and loneliness, and provide more robust data on effectiveness. Research exploring the cost-effectiveness of different approaches is also urgently required in order to further support the development of interventions which address the growing issue of social isolation and loneliness in our expanding older populations.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hope Foundation, New Zealand.

Conflict of interest

None declared.