Self-reported HIV viral load is reliable and not affected by adverse lived experiences of women living with HIV in British Columbia

Abstract

Introduction

HIV viral load (VL) is a key predictor of long-term health for women living with HIV. Here, we investigate how HIV VL self-reported by women living with HIV enrolled in the British Columbia CARMA-CHIWOS Collaboration Study relates to clinically measured HIV VL. Three HIV-related stigma scales and associations with selected socio-demographic characteristics, such as lifetime history of homelessness, history of substance use, ethnicity, and knowledge about ‘Undetectable = Untransmittable’, were also examined.

Methods

For 219 women enrolled between December 2020 and August 2023, self-reported HIV VL status (classified as undetectable ≤40 copies/mL or detectable >40 copies/mL) was compared with HIV VL obtained from chart review closest to, but before the date of self-report (SR). Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios were calculated for the study sample overall and for socio-demographically defined subgroups. Concordance between self-reported HIV VL and (CC) clinical chart-derived values was examined by Cohen's kappa. Three HIV-related stigma scores were compared between women stratified by the concordance of their self-reported and chart review-based HIV VL.

Results

Ninety-five percent (208/219) of women were able to estimate their most recent HIV VL via self-report, and among them, 96% (200/208) were on antiretroviral therapy, 50% reported a history of homelessness, and 30% reported current substance use. Overall, the self-reported HIV VL was correctly estimated by 189 out of 219, and showed high overall concordance (86%) and moderate agreement (Cohen's kappa = 0.55) with HIV VL values derived from CCs. Correctly self-reported undetectable HIV VL showed high sensitivity (97.2%) and positive likelihood ratio (1.92), low negative likelihood ratio (0.06), moderate specificity (50%), and performed similarly across socio-demographic subgroups. HIV stigma scores did not differ between women who estimated their HIV VL correctly versus incorrectly. Of note, knowledge about ‘Undetectable = Untransmittable’ was lower (40%) among women who were not able to estimate their most recent VL than among those who did (74%).

Conclusions

Our findings confirm previous reports of high awareness of HIV VL by women in British Columbia, Canada, despite a high prevalence of adverse socio-demographic experiences in this cohort. Our data further suggest that despite highly stigmatized life experiences, women living with HIV in British Columbia have a strong awareness of their VL status.

INTRODUCTION

Despite global efforts toward equitable HIV treatment and care, lower rates of HIV viral load (VL) suppression are consistently reported among women (vs. men) and racialized women (vs. white women) [1-3]. In British Columbia, Canada, although similar proportions of diagnosed women and men living with HIV are receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) (80% and 79%, respectively), women are less likely to be virally suppressed than men (50% vs. 60% of those diagnosed) [4].

Monitoring HIV VL detectability improves HIV-related health outcomes and mortality, helps understand one's adherence to ART, and supports the Treatment as Prevention approach to reduce HIV transmission [5]. While laboratory assessment of HIV VL is the standard of clinical care, self-reported HIV VL is a valuable metric for research studies, particularly for studies that are community-based, and/or recruit populations inconsistently engaged in care.

Existing data comparing self-reported and clinically measured HIV VL are limited and heterogeneous, with Cohen's kappa coefficients ranging from 0.038 (no agreement) to 0.715 (substantial agreement), depending on the study population and setting [6]. A few studies identified homelessness and other adverse social determinants of health as predictors of discordance, while reports were inconsistent with respect to sex as a predictor [6]. To our knowledge, no reports linked validity of self-reported HIV VL to health literacy outcomes in women, such as awareness about the benefits of ART and knowledge about ‘Undetectable = Untransmittable’ [7].

Herein, we investigate the validity of self-reported undetectable HIV VL in a cohort of women living with HIV enrolled in the community-based British Columbia CARMA-CHIWOS Collaboration (BCC3) study. We also explore whether agreement between self-reported and clinically confirmed HIV VL is associated with various social determinants of health and/or interpersonal and intrapersonal HIV stigma scores—known correlates of low ART adherence and detectable HIV VL [8-10].

METHODS

Study participants

The BCC3 study is a prospective community-based cohort study of women living with HIV and socio-demographically similar women without HIV in British Columbia, Canada [11]. BCC3 enrols cis and trans women ≥16 years old living with and without HIV. The study was approved by the harmonized research ethics board at the University of British Columbia (H19-00896), and all participants provided informed consent. A more detailed description of the BCC3 study is provided in the Supplement.

Study sample and measures of interest

For the present study, we analyzed survey data from all women living with HIV recruited (December 2020–August 2023), who completed the BCC3 clinical visit, including questions about HIV VL.

The main outcome of interest, self-reported HIV VL, was ascertained via a survey question: ‘What was your most recent viral load, undetectable (i.e., below 40 copies/mL) or detectable (i.e., above 40 copies/mL)?’ Self-reported VL was compared with the VL extracted from chart review (undetectable or detectable) closest to but before the date of self-reported VL. Women who had both the self-reported HIV VL and chart review-based HIV VL available were included in the validation analysis. The median [IQR] time elapsed between the estimated date when women self-reported receiving their latest HIV VL and the lab-based VL result obtained from chart review for the analysis was 14 [3–59] days. Only 6% of values were 6 months apart or more, and these were distributed among all concordance groups.

Other self-reported variables included age, time since HIV diagnosis, ethnicity, lifetime history of homelessness, substance use, and being on ART medications. Substance use included opioids, non-opioid sedating drugs, stimulants, and psychedelics, and was categorized as current (self-reported frequency of use ≥ once per month) or past/never. Rurality was ascertained based on self-reported postal code, using a simplified Statistical Area Classification by Statistics Canada. Postal codes within the Census Metropolitan Areas were classified as ‘not rural’ while all other categories were considered ‘rural’ [12]. Chronic pain was ascertained via standardized screening questions endorsed by the clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic pain in patients living with HIV, where chronic pain was defined as a combination of moderate or more severe pain during the last week, and bodily pain for more than three months [13].

Study participants' health literacy about HIV was explored via the questions, ‘How do you think taking ART changes your risk of transmitting HIV?’ and ‘Have you heard of Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U = U)?’. The meaning and significance of the statement were shared with the women who were not familiar with it.

Lastly, we used three self-reported HIV-related stigma scales. The enacted HIV stigma scale explores present or past experiences of discrimination or injustice from others due to HIV status [14]. The score ranges from 9 to 45, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stigma. The HIV-Related Stigma-Disclosure Concerns is a part of the HIV/AIDS-targeted quality of life (HAT-QoL) instrument and examines concerns around HIV disclosure [15]. The score ranges from 6 to 30, with lower scores indicating higher disclosure concerns. The HIV Internalized Stigma scale is a shortened 10-item version of Berger's HIV Stigma scale, where the score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater internalized HIV stigma [16]. These scores were calculated only for women who completed the BCC3 community visit, which typically took place within three months of the clinical visit and completed all scale items.

Statistical analysis

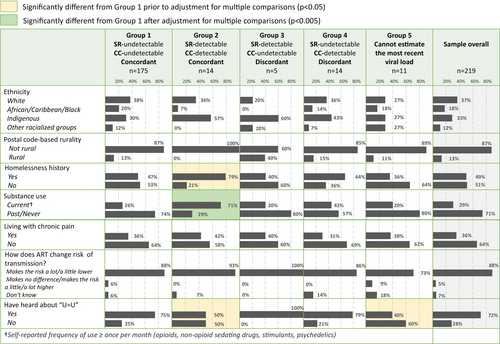

Based on the concordance between SR and CC, women were divided into 4 groups: Group 1 (SR undetectable CC undetectable), Group 2 (SR detectable CC detectable), Group 3 (SR detectable CC undetectable), Group 4 (SR undetectable CC detectable). Women who were not able to estimate their most recent VL were described as Group 5. Groups 2–5 were compared with Group 1. Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's correction for multiple comparisons. Categorical variables were compared by Chi-Squared or Fisher's tests with Bonferroni correction (significance threshold set to p < 0.0045). Analyses were done in GraphPad Prism version 10.1.2. Sensitivity, specificity, and other parameters of interest were calculated in MedCalc [17], with values determined for the full study sample and after stratification by socio-demographic variables that were significant univariately. Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of true undetectable HIV VL (CC) that are correctly self-reported, and specificity as the proportion of true detectable HIV VL correctly self-reported. Cohen's kappa [18] and Gwet's AC1 [19] were calculated as described.

RESULTS

Participant demographics

Of 229 women living with HIV enroled during the study period, 219 had CC data available and were included in the analysis (216/3 cisgender/transgender women), with demographic characteristics summarized in Table S1. Of those, 208 (95%) were able to estimate their most recent HIV VL (i.e., detectable vs. undetectable) and were included in the evaluation of self-reported HIV VL compared with CC-derived values (Figure S1). Out of 208 women included in the comparison, 91% (189/208) correctly estimated their most recent HIV VL, for an overall concordance rate of 86% (189/219) if considering all participants in the study. The median [IQR] time since HIV diagnosis was 19 [11–25] years.

Among women who estimated their most recent VL, 200 of the 208 (96%) were on ART, 180 of the 208 (87%) were undetectable, and 28 of the 208 (13%) were detectable based on the CC data.

Among women who did not provide an estimate of their most recent HIV VL, 8 out of 11 (73%) were on ART, and 5 out of 10 (50%) with CC HIV VL available had a detectable VL (some participants reported receiving HIV VL results but could not estimate them).

Evaluation of self-reported undetectable HIV VL compared with CC values

Validation of self-reported HIV VL compared with the CC-derived values for the whole study sample (n = 208) and sub-groups is shown in Table 1. Self-reported HIV VL showed high concordance (91%) and moderate-high agreement with CC values (Cohen's kappa = 0.55, Gwet's AC1 = 0.89). Overall, self-reported undetectable HIV VL demonstrated high positive 92.6 (95% confidence interval 89.6–94.8)% and negative predictive 73.7 (52.2–87.8)% values. The sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios were comparable between socio-demographically defined subgroups, with overlapping confidence intervals. Concordance was comparable between the subgroups as well (all p > 0.05). While sensitivity and the positive predictive value (PPV) of self-reported undetectable HIV VL were consistently high in our subgroup analyses, specificity and negative predictive values (NPV) showed more variability. Specificity was lowest among African/Caribbean/Black women and women who reported past/never substance use (both 33.3%), meaning that several women in these groups reported being detectable but were in fact undetectable per their CC review. Similarly, NPV was particularly low among those who never experienced homelessness (NPV = 50%), women who reported knowing about U = U (NPV = 58%), and women who reported no current substance use (NPV = 50%), highlighting that half of the women in these groups are undetectable despite self-reported detectable HIV VL.

| Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Negative predictive value, % (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Concordance (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study sample (who provided a self-reported estimate of VL; n = 208) | 97.2 (93.6–99.1) | 50.0 (30.7–69.3) | 92.6 (89.6–94.8) | 73.7 (52.2–87.8) | 1.94 (1.34–2.8) | 0.06 (0.02–0.14) | 91 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| White (n = 77) | 98.5 (92.0–99.9) | 50.0 (18.7–81.3) | 93.0 (87.7–96.1) | 83.3 (39.4–97.5) | 1.97 (1.06–3.66) | 0.03 (0.00–0.23) | 92 |

| African/Caribbean/Black (n = 38) | 100.0 (90.0–100.0) | 33.3 (0.84–90.6) | 94.6 (88.7–97.5) | 100.0 (2.5–100.0) | 1.50 (0.67–3.34) | Not applicable | 95 |

| Indigenous (n = 70) | 94.6 (85.1–98.9) | 57.1 (28.9–82.3) | 89.8 (82.8–94.2) | 72.7 (44.8–89.8) | 2.21 (1.2–4.06) | 0.09 (0.03–0.31) | 87 |

| Other racialized groups (n = 23) | 95.5 (77.2–99.9) | 0.0 (0.0–97.5) | 95.5 (95.0–95.8) | Not applicable | 0.95 (0.87–1.05) | Not applicable | 91 |

| History of homelessness | |||||||

| Yes (n = 104) | 97.6 (91.7–99.7) | 55.0 (31.5–76.9) | 90.1 (84.9–93.7) | 84.6 (56.9–95.8) | 2.17 (1.33–3.53) | 0.04 (0.01–0.18) | 89 |

| No (n = 104) | 96.9 (91.1–99.3) | 37.5 (8.5–75.5) | 94.9 (91.6–97.0) | 50.0 (19.3–80.7) | 1.55 (0.91–2.65) | 0.08 (0.02–0.35) | 92 |

| Knowledge about U = Ua | |||||||

| Yes (n = 153) | 96.3 (91.6–98.8) | 38.9 (17.3–64.3) | 92.2 (89.1–94.5) | 58.3 (33.2–79.8) | 1.58 (1.09–2.28) | 0.10 (0.03–0.27) | 90 |

| No (n = 54) | 100.0 (92.0–100.0) | 70.0 (34.8–93.3) | 93.6 (85.1–97.4) | 100.0 (59.0–100.0) | 3.33 (1.29–8.59) | Not applicable | 94 |

| Substance usea | |||||||

| Currentb (n = 62) | 97.8 (88.5–99.9) | 62.5 (35.4–84.8) | 88.2 (79.9–93.4) | 90.9 (58.1–98.6) | 2.61 (1.38–4.92) | 0.03 (0.00–0.25) | 89 |

| Past/Never (n = 145) | 97.0 (92.5–99.2) | 33.3 (9.9–65.1) | 94.2 (91.5–96.0) | 50.0 (22.2–77.8) | 1.45 (0.97–2.17) | 0.09 (0.03–0.32) | 92 |

- a Data are missing for 1 person.

- b Self-reported frequency of use ≥ once per month (opioids, non-opioid sedating drugs, stimulants, psychedelics). Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of true undetectable HIV VL, as confirmed by a clinical test result that is correctly self-reported by the participant. Specificity is defined as the proportion of true detectable HIV VL, as confirmed by a clinical test result, that is correctly self-reported by the participant.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; U = U, undetectable equals untransmittable.

Comparisons between concordance-based groups

The demographic characteristics of women in each of the 5 groups are summarized in Figure 1. Univariate comparisons of each group with Group 1 yielded differences for three variables: homelessness, substance use (both higher in Group 2 vs. Group 1), and knowledge about U = U (lower in Groups 2 and 5 vs. Group 1). However, only substance use remained significantly different after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

There was no significant difference between groups for any of the three HIV-related stigma scores (Figure S2). Of note, the median HIV-related Stigma–Disclosure concerns score among women who did not report their most recent HIV VL (Group 5) was 4–8 points lower than that in other groups, suggesting heightened disclosure concerns, although not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Overall, our findings confirm that self-reported undetectable HIV VL is a reliable measure of VL in a cohort of diverse women living with HIV in British Columbia, Canada. Measures of sensitivity and specificity were comparable between women across ethnic groups and despite adverse socio-structural experiences, such as substance use and history of homelessness, highlighting high ART adherence and awareness of HIV health parameters. While self-reported undetectable HIV VL was highly predictive of true undetectability overall and across subgroups, self-reported detectable HIV VL was not, whereby, almost half of the women who reported detectable HIV VL in some groups were, in fact, undetectable when their last VL was measured. Comparisons between the groups stratified by concordance between SR and CC-derived values in our analysis yielded few differences—likely due to limited sample size. Notably, 14 women in our study reported undetectable HIV VL while being detectable based on CC data, further emphasizing the need for health literacy, education, and empowerment in clinical visits to ensure that women are fully informed about their HIV health parameters.

Our observations are comparable with those of the CHIWOS study, a cohort of women living with HIV across Canada, where ethnicity, education, and recent substance use were not associated with the validity of SR among women in British Columbia [20]. Another study in the Pacific Northwest reported a similar level of agreement among women (kappa = 0.53) to the one seen in our analysis (kappa = 0.55) [21]. Our finding of high reliability of self-reported HIV VL among women who report socio-structural adversities is in contrast with a few studies identifying homelessness and other similar factors as predictors of discordance between self-reported and clinical values [22, 23]. This discrepancy could reflect differences in study settings, in the questions used to obtain self-reported HIV VL, or in data collection modality.

Our findings around self-reported HIV VL validity and awareness about ‘U = U’ and efficacy of ART are consistent with a 2021 study of ‘U = U’ awareness done in 25 countries, and suggest an opportunity for health promotion among groups with low awareness [24]. It has been suggested that ‘U = U’ messaging be universal during HIV care visits, as it offers an incentive to maintain suppression [25] and decreases HIV-related stigma [26, 27].

Our findings should be viewed in light of a few limitations. First, our analyses are limited by a small sample size, which likely contributed to wide confidence intervals, and a strict definition of undetectable HIV VL (<40 copies/mL). Next, our ‘U = U’ question does not ascertain the source of knowledge, which limits our understanding of actionable ways to improve HIV-related health literacy in the cohort. We also did not estimate HIV VL performance stratified by high/low stigma scores due to missing data concerns for that variable. Lastly, while we did consider rurality, an important factor influencing access to the continuum of HIV care [28], the majority of women in our cohort reside in urban areas and are linked to regular HIV care, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings to rural settings or women not actively engaged in care.

CONCLUSIONS

Women living with HIV in British Columbia are generally well aware of their HIV suppression status regardless of adverse socio-structural experiences, making self-reported HIV VL a reliable HIV care outcome for studies relying on SR. Further research is warranted to identify correlates of discordance between self-reported and clinically confirmed HIV VL, with a particular focus on actionable strength-based approaches.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: T.P. and H.C.F.C. Methodology: T.P. and S.A.S. Formal analysis: T.P. Data curation: T.P., M.A.P.S., S.A.S., S.T. and M.L. Writing–original draft preparation: T.P. Writing–review and editing: T.P., S.A.S., M.A.P.S., S.T., M.L., E.M.K., Z.O., A.K., M.C.M.M. and H.C.F.C. Visualization: T.P. Supervision: H.C.F.C. Project administration: M.A.P.S. Funding acquisition: H.C.F.C., M.C.M.M. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are thankful to all women who participated in the BCC3 study and made this work possible. This work was conducted on behalf of the BCC3 study team on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of the Coast Salish peoples, including the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations. In addition to the authors listed here, the BCC3 study team includes co-principal investigators Valerie Nicholson and Drs. Jason Brophy, Neora Pick, Allison Carter, Carmen Logie, Kate Salters, Mona Loutfy, Jerilynn Prior, and Joel Singer, as well as trainees/research staff Charity Mudhikwa, Julliet Kien Zama, Loulou Cai, Dr. Monika Kowatsch, Davi Pang, Franceska Dnestrianschii, Amber R. Campbell, Vyshnavi Manohara, Sofia Levy, Camille Valbuena, and Zhou Fang.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The British Columbia CARMA-CHIWOS Collaboration (BCC3) has received funding support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Project Grants (PJT-162348, PJT-175006), CIHR Community-Based Research Grant (CBR-170103), and Women's Health and Mentorship Grant (F19-05017); CIHR HIV Clinical Trial Network Support (CTN 335) and Pilot Grant Funding (CTNPT 046, CTNPT 050); UBC Partnership Recognition Fund; UBC Community-University Engagement Support Fund, and UBC Public Scholars Initiative; Simon Fraser University's Community Engagement Initiative; and Michael Smith Health Research BC (trainee award). AK received a salary support award from the Canada Research Chair Program. MCMM received salary support from the Michael Smith Health Research BC Health Professional Investigator Award. TP received funding from the UBC Four Year Doctoral Fellowship and UBC Centre for Blood Research Graduate Award Program.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.