The Experience of Manual Wheelchair Training for People With Chronic and Progressive Conditions: Perspectives of Users and Trainers

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Global ageing and the rise of chronic and progressive health conditions that lead to mobility changes will see increased need for manual wheelchair (MWC) provision and training. Existing training guidelines and training programmes are frequently tailored towards younger users. There is a knowledge and practice gap regarding the needs of people with chronic or progressing conditions who require a wheelchair. To inform practice guidelines and training practices, this study sought the perspectives of both MWC users and trainers on their experience of MWC training.

Methods

Using a qualitative descriptive approach, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with 11 MWC trainers and 6 MWC users. Data from the two participant groups were inductively coded and thematically analysed using NVivo and concept mapping to synthesise the data into themes and sub-themes.

Results

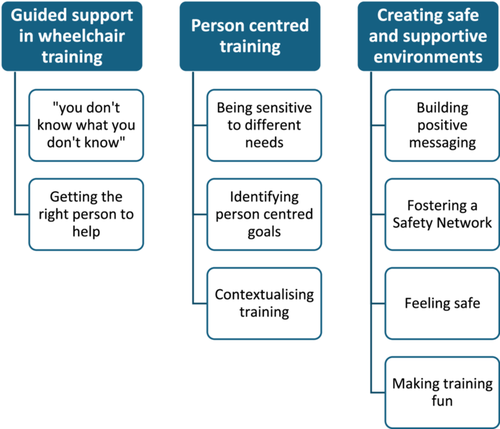

Three main themes were identified: guided support in wheelchair training reflected the need for basic support when commencing wheelchair use, person-centred training recognised the importance of tailoring training to individuals, their goals and contexts, and creating safe and supportive environments addressed how to foster acceptance of training through building a supportive training environment.

Conclusion

Access to skilled MWC trainers is essential for MWC users commencing MWC use due to a chronic or progressive condition; however, the Australian healthcare system does not currently meet this need. There is a need to explore alternate models of service delivery, such as peer-led training or upskilling of other key stakeholders, such as assistive technology suppliers. The creation of supportive environments and tailored training aligned with the abilities and goals of individual users must take precedence over resource-driven or one-size-fits-all approaches.

Patient Contribution

During the development of semi-structured interview guides, feedback was sought from an MWC user and MWC trainer to ensure the relevance and appropriateness of the questions and allow for the refinement of questions.

1 Introduction

Quality manual wheelchair (MWC) training can promote safety, independence and community participation for MWC users. This outcome can reduce health service use and reliance on informal carers [1]. Global demographic data suggests that 1% of the population requires a wheelchair to assist with mobility, and this requirement is predicted to grow with an increase in the older population and the prevalence of chronic and progressive conditions [2]. This trend in wheelchair use makes the provision of quality MWC training essential [2]. Wheelchair training has received some attention with recently published guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) [2] and guidelines prepared about upper limb preservation for wheelchair users [3]. While existing MWC training guidelines [2, 3] provide a valuable foundation, they are broad in nature and are not designed to meet the specific needs of different MWC users.

MWC users with chronic or progressive conditions are often older and may have reduced physical capacity (i.e., reduced strength, flexibility and endurance) [4], cognitive or sensory impairments [5], low confidence [4] and limited motivation to engage in training [6]. These factors highlight the need for training programmes that accommodate their functional abilities, slower learning pace, and lower confidence and motivation. Existing MWC training programmes, including WheelSeeU [7], Roulez Confiance (Rolling with confidence) [8], TEAM Wheels [9], EPIC Wheels [10] and the Wheelchair Skills Program [11], are of high quality but are largely designed and resourced for younger MWC users. This may leave MWC users who come to wheelchair use later in life due to a chronic or progressive health condition with insufficient or unsuitable training for their needs [12-14].

Existing literature provides insight into MWC training for older users that may also be relevant for those with chronic or progressive conditions. This includes recommendations about what content needs to be included in MWC training for this population and the types of physical environments that are valued [4, 15, 16]. Literature also suggests positive outcomes from group-based [4, 17] and peer-led training approaches [4, 17, 18]. While this attention to the needs of this population is positive, there remains a lack of understanding around how to support and adapt training to meet the needs of MWC users who may have reduced physical conditioning or cognitive and/or sensory changes that may impact how MWC training is taught. It is also unclear what supportive elements could be implemented to enhance confidence, address fear and anxiety and motivate users to engage in MWC training to facilitate safe MWC use.

Knowing more about the MWC training needs for users with progressive and chronic conditions, how MWC training is currently delivered, and the experiences of MWC users and trainers could lead to the development of recommendations for programmes that are tailored to their needs. This practice change may decrease injury risk for MWC users with progressive and chronic conditions, increase independence and social engagement, and reduce caregiver and health system strain. The following research question guided this exploration: ‘What are the perspectives of MWC users who commence wheelchair use due to a chronic or progressive condition, and the training providers who support them, regarding MWC training?’.

2 Methods

This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [19]. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research and Ethics Committee at the University of Adelaide (H-2023-290).

2.1 Study Design

A qualitative descriptive approach gathered insights from individuals who use wheelchairs due to chronic or progressive conditions, their caregivers and MWC training providers in relation to their experience of MWC training. The semi-structured interview design allowed for open-ended questioning with follow-up probing questions and deep exploration of participants' thoughts, feelings and beliefs [20]. This approach kept interpretations of findings close to the data [21, 22].

2.2 Sampling and Recruitment

MWC users who commenced MWC use as an adult due to chronic or progressive conditions, caregivers, and providers of MWC training for this population were purposively sampled by the first author (K.C.). A chronic condition was defined as a health condition typically persisting over 3 months and a progressive health condition, which may worsen over time or require continuous management for its persistent effects [23]. Given that many people living with chronic and progressive conditions will acquire an MWC, due to affordability and availability, this study focused on MWC users and excluded people who solely used power wheelchairs. Individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) were excluded from this study due to the substantial body of existing research focused specifically on MWC training for this population; however, trainers of individuals with SCI were included on the provision that they had experience in training individuals with chronic or progressive conditions. See Table 1 for full eligibility criteria. Recruitment occurred via social media platforms, Australian-based assistive technology, aged and disability care organisations, Australian professional assistive technology bodies, allied health managers within healthcare services and snowball sampling, where participants referred other eligible individuals. The sample size was determined iteratively during data analysis [24].

| Population | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Providers of MWC training |

|

|

| Manual wheelchair users |

|

|

| Caregivers of MWC users |

|

|

2.3 Data Collection

Participants provided demographic information via a Qualtrics survey (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah, the United States) and provided written or verbal consent before the interview commenced. The first author (K.C.) conducted individual semi-structured interviews online via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications Inc.). Separate interview guides were developed for MWC trainers and MWC users based on findings from a recent scoping review on wheelchair training approaches [1]. The interview guide was piloted with an MWC trainer and an MWC user who were ineligible for the research and known to the research team. The guide was refined based on feedback. See Table 2 for interview guide questions. Interviews took place over a 11-month period from January 2024 to November 2024 and lasted an average of 50.58 ± 7.93 min. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

| MWC trainer | MWC user | |

|---|---|---|

| General experience of training |

|

|

| Understanding of how existing MWC training supports users with chronic or progressive conditions |

|

|

| Suggestions for improving MWC training |

|

|

| Concluding thoughts |

|

|

2.4 Data Analysis

Braun and Clarke's six-phase inductive reflexive thematic analysis was used to identify, analyse and report themes [24]. Reflexive thematic analysis was chosen due to it being a well-established method for qualitative data analysis to identify patterns of meaning across data. Initially, data from MWC trainers and MWC users were analysed separately to ensure the voice of both groups was retained and centred across the data analysis and interpretation. The first author (K.C.) undertook multiple reviews of each transcript to understand the breadth and depth of the data, generating initial codes with descriptors and inductively sorting codes of similar meaning into categories using the NVivo qualitative software platform (QSR International Pty Ltd). The descriptions and initial categories were shared with and discussed among the research team, leading to further refinement. Findings from the MWC users and the MWC trainers were then combined using a concept mapping approach [25], which enabled identification of any overlapping, complementary and divergent data in the categories. A refined set of integrated themes was developed, incorporating both shared and unique elements across the two participant groups. These themes and sub-themes were examined by the whole research team against the research question and were further refined to arrive at main themes with detailed memos documenting the rationale behind each theme. Table 3 shows an example of the relationship between a theme, sub-theme, code and transcript data. Thick descriptions of the data and direct quotations were used to ensure the confirmability of the author's interpretation.

| Raw transcript data | Code | Sub-theme |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Guided support in wheelchair training | ||

| ‘I regret not asking questions so much earlier. I'm in touch with other people in wheelchairs, and they will be like, can't you flip your front wheels up?’ (Delilah—MWC user) | You don't always know what you might need to learn and what is important until it is too late. | ‘You don't know what you don't know’ |

| ‘I had the wrong team initially, when I was in hospital. I think if I'd had a different team behind me, I would have got up and been doing things a whole lot quicker.’ (Debbie—MWC user) | Having trainers who know what they are doing is important | Getting the right person to help |

| ‘I wanted to basically know the best way to push with the least amount of energy. It took me a long way to figure out, and I'm still probably not even doing it right.’ (Chris—MWC user) | Biomechanical education is important | Addressing the basics |

| Theme 2: Person-centred training | ||

| ‘My body is different to every other body. I've got really little arms, I've got contractures. There is no body like mine, and I would say the same for everyone else. So that needs to be considered when training is provided’ (Delilah—MWC user) | Every MWC user is different in their body size and their abilities, so training needs to be tailored to an individual's needs. | Being sensitive to different needs |

| ‘It's important to ask questions like; where in your local community do you want get to? Where do you go and what do those environments look like? Are you a public transport user? It's about sort of, navigating what their needs are within their local community and lifestyle to shape how training will look.’ (Bianca—MWC Trainer) | Considering the goals of a person and matching training to one's goals would be beneficial | Identifying person-centred goals |

| ‘It would have been better to take me out into a shopping mall or plaza to give me an open environment with different surfaces and different things to manoeuvre around, because that potentially is where you're going to be using it [the wheelchair] the most.’ (Michelle—MWC user) | Completing training in contextually relevant places is important | Contextualising training |

| Theme 3: Creating safe and supportive environments | ||

| ‘Family and friend relationships make a big difference. If family and friends are very positive about wheelchair use, then that patient is more motivated. If family and friends are like not then that makes it harder for the patient to accept.’ (Francesca—MWC trainer) | Having family and friends who are positive about wheelchair use and the benefits supports acceptance of MWC training and use | Building positive messaging |

| ‘Even if we're outdoors or something, I'll just sort of have a bit of chat about stuff and not just make it so focused on the wheelchair skills unless you know they've got some cognitive concerns, and you don't want them to be distracted. But yeah, I usually try and kind of keep it quite light.’ (Phoebe—MWC trainer) | Having informal conversations not related to MWC training helps users relax and feel more comfortable engaging with training | Fostering a safety network |

| ‘It helped when he was behind me as I was giving it a go, because he making sure that I wasn't gonna tip. I had to tip bars on, but he was making sure I didn't do anything else.’ (Delilah—MWC user) | Having anti-tips or someone stand behind when completing wheelies can make the user feel safer when completing skills | Feeling safe |

| ‘We've got a number of sort of drills that we would send them home with like seeing how long you can get from one push or in a hallway see how few pushes you can do to get to the other end just to get them more confident with releasing the wheels and letting the wheelchair do some of the work for them in a more fun way.’ (Bianca—MWC trainer) | You can use drills or gamify training to support an efficient propulsion style | Making training fun |

2.5 Rigour

Credibility of findings was supported through use of a reflexive journal and peer debriefing before and during data gathering and analysis. Inclusion of a clear position statement acknowledges and supports the management of any subjectivity and assumptions that may have been held by the research team [26]. Supporting quotes from participants are used to illustrate themes. Data collection over an 11-month period allowed for prolonged engagement and familiarity with the data and enabled iterative refinement of interview techniques. The first author maintained an audit trail of analytical decisions to allow backtracking and ensure the dependability of the final themes and confirmability of findings, which were strengthened through all members of the research team being involved in data analysis.

2.6 Author Positioning

The primary author is an occupational therapist and PhD candidate with experience in MWC training with people with chronic, progressive and ageing conditions within inpatient and community settings. This first-hand experience provided insights into the challenges in providing and receiving high-quality MWC training and has been the motivation for this study.

The co-authors have occupational therapy and speech pathology backgrounds. All authors have experience in conducting qualitative research.

3 Results

3.1 Participants

Seventeen people from four states and one territory of Australia were recruited for this study. Demographic information is listed in Tables 4 and 5. Six MWC users (4F, 2M) participated in interviews. MWC users had an average age of 55.5 ± 14.74 years, and experience in MWC use ranged from 3 to over 15 years (average 6.25 ± 4.53). MWC use was related to lower limb amputations secondary to chronic conditions (n = 3), multiple contributing conditions (n = 2) and post-polio syndrome (n = 1). Three users obtained a wheelchair while living in the community, and three within an inpatient setting, and all reported receiving minimal to no MWC training. All MWC users resided within Australia, with the majority living in urban areas (n = 5). MWC trainers (9F, 2M) participated in interviews, representing a range of training experiences, from emerging (0–5 years) to over 30 years. MWC trainers were most commonly occupational therapists (n = 6), followed by peer wheelchair trainers (n = 3), exercise physiologists (n = 1) and allied health assistants (n = 1). Training delivery experience was across government agencies (n = 8) and private practice settings (n = 8) and within both inpatient (n = 8) and community (n = 7) environments. The trainers predominantly provided their service to adult MWC users, including those with neurological conditions, amputations, orthopaedic injury and SCI. All participants were assigned pseudonyms, which are used to report the findings.

| Participant pseudonym | Gender | Age | Duration of MWC use | Reason for MWC use | Setting MWC was first obtained | Reported level of training provided | State MWC obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delilah | Female | 28 | 2–5 | Multiple contributing conditions | Community | Minimal training from the AT provider | NSW—Major Urban |

| Lisa | Female | 70 | 10–20 | Post polio | Community | No training provided | ACT—Major Urban |

| Chris | Male | 64 | 2–5 | Multiple contributing conditions | Community | No training provided | QLD—Regional |

| Michelle | Female | 52 | 5–10 | Lower limb Amputee | Inpatient | No training provided | SA—Major Urban |

| Frank | Male | 61 | 2–5 | Lower limb Amputee | Inpatient | Minimal training provided by OT | SA—Major Urban |

| Debbie | Female | 58 | 2–5 | Lower limb Amputee | Inpatient | Minimal training provided by OT | SA—Major Urban |

- Abbreviations: ACT = Australian Capital Territory, AT = assistive technology, MWC = manual wheelchair, NSW = New South Wales, QLD = Queensland, OT = occupational therapist, SA = South Australia.

| Participant pseudonym | Gender | Years of MWC training experience | Professional background | Practice setting | Training location | MWC user demographics | State training provided within |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laura | Female | 10–20 | EP | Private | Community | Adults—various conditions, including neurological and SCI | Victoria—Major Urban Population |

| Hannah | Female | 20–30 | OT | Public and private | Inpatient and community | Adults—various, including degenerative conditions and SCI | Victoria—Major Urban Population |

| Vince | Male | 10–20 | Peer MWC Trainer | Private | Community | Adults—various, including MS, amputees, spina bifida and SCI | NSW and Victoria—Major Urban Population |

| Kane | Male | 5–10 | Peer MWC Trainer | Public and private | Community and inpatient | Adults—various, including MS and other degenerative conditions and SCI | Victoria—Major Urban Population |

| Melissa | Female | 0–5 | Peer MWC Trainer | Public and private | Community and inpatient | Children and adults—various, including amputees, spina bifida and SCI | Victoria—Major Urban Population |

| Veronica | Female | 0–5 | OT | Private | Community | Adults—various, including MS, general rehabilitation, cuada equina and SCI | South Australia—Major Urban Population |

| Francesca | Female | Over 30 | AHA | Public | Inpatient— subacute | Adults—mostly stroke, other neurological conditions and amputees | South Australia—Major Urban Population |

| Libby | Female | 10–20 | OT | Public | Inpatient— subacute | Adults—stroke, ABI, other neurological conditions, amputees and SCI | South Australia—Major Urban Population |

| Bianca | Female | 5–10 | OT | Private and public | Inpatient—acute/subacute and community | Adults—various conditions including stroke, MS, other neurological conditions, amputees and orthopaedics | South Australia—Major Urban Population and the UK |

| Pheobe | Female | 5–10 | OT | Private and public | Inpatient— acute/subacute | Adults—various conditions including neurological conditions, amputees, bariatric clients, orthopaedics and SCI | South Australia—Major Urban Population and the UK |

| Kristen | Female | 10–20 | OT | Public | Inpatient— subacute | Adults—various conditions including neurological conditions, amputees, orthopaedics, Guillain-Barré and SCI | South Australia—Major Urban Population and the UK |

- Abbreviations: ABI = acquired brain injury, AHA = allied health assistant, EP = exercise physiologist, MS = multiple sclerosis, MWC = manual wheelchair, NSW = New South Wales, OT = occupational therapist, SCI = spinal cord injury, UK = United Kingdom.

Experiences of wheelchair training from the perspective of users who began MWC use due to a chronic or progressive condition and of MWC trainers are presented across three themes and nine sub-themes. Figure 1 provides an overview of themes and sub-themes, which are explored below.

3.2 Theme 1: Guided Support in Wheelchair Training

The data provided insights into MWC users' experiences of receiving limited guidance or training in MWC use and the consequences of this, as well as suggestions on who should support training and what training should encompass.

3.2.1 ‘You Don't Know What You Don't Know’

‘I knew nothing. Which actually is why the incident [fall from MWC] happened, because I didn't know what I was doing.’

Michelle—MWC user

‘It got to the stage that I didn't feel safe, and I didn't feel comfortable [in the MWC]. So I then forced myself when I went out in the public to use my walking sticks. That put me at an increased risk of falls and overheating, and overexertion will bring on seizures.’

Chris—MWC user

‘It would have been good to learn basically the best way to push with the least amount of energy … it took me a long time to figure it out, and I'm still probably not even doing it’.

Delilah—MWC User

‘I couldn't push myself up any slope…. So I would have support workers, drop me to work, push me down the hill into work, and then they would come at 5pm and do the same thing.’

Delilah—MWC user

3.2.2 Getting the Right Person to Help

‘We need to have the training and the confidence to present something because otherwise if we go in half hearted, then we sound like we don't know what we're talking about, then that doesn't give clients confidence in us.’

Veronica—OT

‘I went for about 6 months, not being able to get one [an OT] because there just wasn't anybody free to help.’

Lisa—MWC user

‘Lots of people have told me this. They say you've been my inspiration. I saw you do this, and I thought, Well, if she can do it, I'll give it a go, too.’

Melissa—Peer MWC Trainer

‘I think the OTs [occupational therapists] should be the ones involved in training, because we do home visits and function, retraining all of that.’

Kristen—OT

3.3 Theme 2: Person-Centred Training

MWC users and trainers recognised the diverse abilities, goals and stages of readiness of those requiring wheelchairs. This theme emphasises the importance of tailoring training to individuals, creating person-centred goals and delivering contextually appropriate training.

3.3.1 Being Sensitive to Different Needs

‘They had a set of things they got me to do and then that was it’

Debbie—MWC user

‘You've got to consider things like, do they even have upper limb strength to push themselves?’

Bianca—OT

‘Sometimes people aren't ready yet, like emotionally for a wheelchair. A lot of people have trouble accepting their injury and adjusting to their injury.’

Libby—OT

‘We use the 4 C's. You have to show correct technique, consistently, you must appear confident, feel comfortable doing it, and you have to show that skill at least 4 times before we move on.’

Melissa—Peer MWC Trainer

‘So particularly with the older population … giving that practical demonstration, visually showing them makes a lot of difference.’

Phoebe—OT

3.3.2 Identifying Person-Centred Goals

‘It tends to highlight the things that are possible in a chair and determine whether or not that's a goal for that person … so we use that assessment (WST-Q) to guide the conversation about what their goals are’.

Laura—EP

‘If you get that easy win you've then got them the whole way, because once they've seen the value in it, they'll then go right, Okay.’

Vince—Peer MWC Trainer

Despite the emphasis on goals led by MWC users, all participants acknowledged that training is often shaped by the setting. In acute care, the focus is typically on ensuring safe hospital discharge, rather than addressing broader, person-centred goals. This practice can result in training that does not progress beyond basic skills or extend to outdoor or advanced skills, even when MWC users and trainers recognise the importance of such skills.

3.3.3 Contextualising Training

‘The initial training in a hospital if you are just in a safe environment. You're only ever gonna expect it to be safe. And life's not like that.’

Frank—MWC user

Despite this recognised importance, MWC trainers explained that resource limitations often restricted the provision of these training opportunities, leaving users reliant on others to navigate unpredictable environments. To address this, some hospital-based trainers utilised purpose-built facilities or nearby community areas to teach mobility skills, but MWC users noted that these settings did not always reflect real-world challenges.

3.4 Theme 3: Creating Safe and Supportive Environments

Engaging in MWC training can be challenging, making it essential to create a safe, supportive environment. This theme discusses fostering acceptance of training through building a supportive network, creating a sense of safety and making training fun.

3.4.1 Building Positive Messaging

‘Part of that emotional journey is the shame that you feel, the embarrassment that you feel to start off with. When you come to this later in life, the sense of a loss of freedom.’

Chris—MWC user

‘A lot of patients are very resistant to being in a chair, and they're like, I won't be needing this, because I will be walking.’

Francesca—AHA

‘The physiotherapist would be working on them every day to get them to the point that when they left the hospital they could walk. Maybe 5 meters. Being able to walk 5 meters, is not functional’

Vince—Peer MWC Trainer

‘Sometimes with rehab, you need to have the family on side … because the people that you trust are often the ones that will get you going.’

Debbie—MWC user

‘Getting back out to smoke and not being able to do it in hospital grounds. That really motivates.’

Bianca—OT

3.4.2 Fostering a Safety Network

MWC trainers saw the need to engage in informal conversations to foster supportive, emotionally safe learning environments and positive trainee–trainer relationships. Hierarchical dynamics between allied health professionals and MWC users were seen to create power imbalances, reduce a user's confidence and discourage open communication.

‘Being surrounded by people that are learning the same skills, I think that's a really big support in terms of their learning.’

Melissa—Peer MWC Trainer

‘It would make them feel more comfortable if they've got a family member there.’

Libby—OT

‘There is quite a lot out there that makes it seem like everyone can do that [go up and down stairs] with a wheelchair. But, probably only 10% can actually do it in a wheelchair’

Michelle—MWC user

3.4.3 Feeling Safe

‘He was behind me as I was giving it a go, making sure that I wasn't gonna tip.’

Delilah—MWC User

‘I found teaching those skills in a closed environment much easier and then transitioning to the community.’

Laura—EP

‘The average person who goes into a wheelchair has no idea.’

Chris—MWC User

3.4.4 Making Training Fun

‘Make it fun. If you're training with OTs, get them to have a kit bag of things that make training fun.’

Debbie—MWC user

‘Generally having that license to have a bit of fun helps to break the ice for everyone. I think the wheelchair becomes something different. It doesn't become a symbol of defeat and injury and disability and trauma.’

Vince—MWC Trainer

Suggestions for building fun included: incorporating music into training, icebreaker activities and gamifying training to support efficient propulsion style. Incorporating social elements like morning tea or informal networking before or after training was also suggested by Vince (Peer MWC trainer) to encourage relaxed ‘car park’ or ‘sideways’ conversations, where people feel comfortable to ask questions and share experiences.

4 Discussion

This study gathered the perspectives of MWC users with chronic or progressive conditions and MWC trainers on their experiences of training, to explore ways to support the physical needs, confidence and engagement of this population. Three key themes emerged from the experiences of MWC training in both participant groups. These included the need for guidance from knowledgeable trainers, the value of person-centred approaches and the need for safe, supportive environments for learning.

Both MWC users and trainers in this study identified peer-led training as being valuable for building confidence and motivation, due to the relatable insights and support that peers can provide. This finding is consistent with other peer-led MWC training programmes, which suggest that peer-led training is effective for building trust, motivation, engagement, self-efficacy and skill acquisition [8, 9, 17, 27-29]. As such, expanding existing peer-led initiatives in Australia, such as Skills for Independence [30], could enhance both accessibility and effectiveness of training delivery for this population of MWC users.

While peer-led training may be one mechanism to support the self-efficacy and motivation for MWC training in those with chronic or progressive conditions, a person-centred approach was also recognised in this study to be essential for maintaining an MWC user's motivation and ensuring that physical and cognitive needs are met. Consistent with other MWC training research, users are more likely to remain engaged and invested when training is tailored to their goals [4, 6, 8-10, 27, 31, 32], provided within environments that are important and contextually appropriate for the user [17, 27, 33-35], and flexible and adaptable to meet the content and pace of an individual user [7, 18, 28, 29, 36]. This approach aligns with self-determination theory [37], which highlights that when MWC users feel in control and find that training is relevant to their learning, there is a greater sense of autonomy and empowerment. This outcome will foster intrinsic motivation, thus contributing to engagement in training and improved safety, confidence and independence.

Accessibility to MWC training also came up as an issue in the research. Accessibility may be enhanced through upskilling those around the MWC user such as allied health assistants, assistive technology providers and carers through opportunities, such as WHO's online Training in Assistive products (TAP) [38], International Society of Wheelchair Professionals (ISWP) training programmes [39] and WHO wheelchair service provision training packages [40]. Incorporating caregivers into training was endorsed by the WHO's Wheelchair Provision Guidelines [2] and reinforced by existing MWC training literature [17, 34]. Stronger relations and referral pathways between primary healthcare providers (i.e., general practitioners), assistive technology retailers, hospital staff and community-based MWC training providers could also improve access to MWC training. This approach aligns with contemporary recommendations from the WHO/UNICEF [41] to develop capability and capacity across health and social sectors. These are feasible suggestions for increasing access to MWC training and therefore improving efficient MWC propulsion.

Creating a safe, positive and supportive learning environment was important to enhance the MWC user's self-efficacy. This learning includes reframing MWC use as a path to independence rather than associating it with a loss of independence. Inclusion of caregivers in training is one way to enhance safety, reinforce positive attitudes and sustain motivation. Group training is also recognised in the literature as creating positive learning environments through a sense of community [4, 7, 8, 27]. Group environments allow users to observe others succeeding, which helps them believe in their own ability to achieve similar outcomes. This relationship reflects Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory [42], which emphasises the role of observational learning, social reinforcement and self-belief in shaping motivation.

5 Strengths and Limitations

This study captured an Australian perspective of MWC training across a range of healthcare settings, providing a well-rounded understanding of current practices and challenges in MWC training delivery. Whilst we intended to recruit MWC users who had accessed training, all MWC users interviewed expressed receiving little to no MWC training, highlighting systemic barriers within the Australian healthcare system. These challenges may stem from MWC training remaining a hospital-centric service delivery model, where training is led primarily by health professionals working in under-resourced environments with a strong focus on discharge planning. Access may also be limited by fragmented community-based supports, which vary depending on locality, age and individuals' financial resources. As the contexts of wheelchair use and training differ across countries, the findings of this study may not translate beyond Australia; however, a lack of guidance and education in MWC use has been reported in other high-income countries, including Canada [12, 14, 43] and the United Kingdom [13]. Therefore, suggestions and insights generated through this study may have implications for MWC training internationally.

While the research gathered insights from experienced MWC trainers, working across diverse healthcare settings, most trainers had more experience in working with younger MWC users (i.e., SCI) than those with chronic and progressive conditions. Additionally, only six MWC users were interviewed in this study, and those who participated were eager to engage in this study as a mechanism to support and advocate for a change to the delivery of MWC training. This study, therefore, did not capture the perspectives of MWC users who had received comprehensive MWC training, or MWC users who were less engaged, nor did it capture caregiver perspectives. These results may therefore not fully reflect the diversity of MWC training experiences.

6 Conclusion

This study highlights gaps in MWC training for individuals with chronic or progressive conditions, emphasising that the current Australian healthcare system does not meet the needs of these users. There is a need to explore alternate models of service delivery, such as peer-led training or upskilling of people around the MWC user to meet this need. A person-centred approach that prioritises goal-directed training, tailored to the physical and cognitive needs of the user and delivered within contextually relevant environments, is critical for fostering engagement and meaningful skill development. When considering the delivery of MWC training, leveraging principles from social cognitive theory and self-determination theory could be used to provide enhanced motivation and self-efficacy to support positive outcomes for MWC users.

Author Contributions

Kimberly Charlton: conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Carolyn Murray: conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, formal analysis, writing – review and editing. Natasha Layton: conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, formal analysis, writing – review and editing. Stacie Attrill: conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, formal analysis, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the participants of the study, as well as Pete Donnelly, Yvonne Duncan and Larnie Ball for their input during the research process. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley - The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.