Prophylaxis with FEIBA in paediatric patients with haemophilia A and inhibitors

Summary

The benefits shown with factor VIII (FVIII) prophylaxis relating to joint health and quality of life (QoL) provide the rationale for FEIBA prophylaxis in haemophilia A patients with persistent FVIII inhibitors. FEIBA has previously shown efficacy in preventing bleeds in inhibitor patients who failed to respond to, or were ineligible for immune tolerance induction (ITI). The study examined the outcome of paediatric patients undergoing long-term FEIBA prophylaxis. A retrospective chart review included severe haemophilia A patients with persistent inhibitors aged ≤13 years at the start of FEIBA prophylaxis. Baseline characteristics captured dose, frequency of prophylaxis, history of inhibitor development, including baseline titre, historical peak titre and history of ITI. Outcome measurements included annual bleed rate before and during FEIBA prophylaxis, joint status and school days missed. Sixteen cases of FEIBA prophylaxis from two centres are presented. The mean age of subjects at prophylaxis initiation was 7.5 ± 3.6 years and median baseline inhibitor titre was 23 (range 3.1–170) BU. Prior to prophylaxis initiation, median annual joint bleeds among all patients was 4 (0–48), which dropped significantly after the first year of prophylaxis, to a median annual joint bleed rate of 1 (0–7; P = 0.0179). Subsequent years (median = 9) of prophylaxis therapy demonstrated similarly low annual joint bleed rates. There were no life-threatening bleeds, no viral seroconversions or thrombotic events during FEIBA prophylaxis treatment. FEIBA prophylaxis was effective for preventing joint bleeds and subsequent joint damage, delaying arthropathy and improving outcomes in children with haemophilia A and inhibitors to FVIII, who failed or were ineligible for ITI.

Introduction

Prophylaxis therapy with factor VIII (FVIII) in patients with haemophilia A is known to be highly effective in preventing development of haemarthroses and subsequent joint damage 1-6. Haemophilia patients who begin a primary prophylaxis regimen early in life and continue on their prescribed regimen experience significantly better quality-of-life outcomes compared to patients who treat bleeding episodes on an ‘on-demand’ basis 7. On-demand treatment addresses bleeds as they occur but is insufficient to prevent arthropathy.

Factor VIII neutralizing inhibitors develop in approximately 30% of severe haemophilia A patients 8. As a result of clinically relevant inhibitor development, FVIII treatment is rendered ineffective for the treatment of bleeding episodes. Bypassing therapy such as activated prothrombin complex concentrate (FEIBA; Baxter Healthcare, Westlake Village, CA, USA) and recombinant activated factor VIIa (NovoSeven; Novo Nordisk, Badsvaerd, Denmark) are safe and effective treatments for managing bleeding episodes in the presence of FVIII inhibitors 9-13. The proven benefits of FVIII prophylaxis in haemophilia A patients without inhibitors provide the rationale for the usage of bypassing agents prophylactically in patients with FVIII inhibitors. Previous studies using FEIBA for the treatment of an acute bleeding episode have shown that haemostasis was achieved in 80–90% of bleeding episodes 9, 14-18. Prophylactic treatment with FEIBA in inhibitor patients aims to prevent joint and soft tissue haemorrhage and reduce joint damage and consequent disability 19, 20. Haemophilia patients with inhibitors not only suffer from more pain and morbidity compared to non-inhibitor patients, but also miss more time from school or work and require more frequent hospitalization 21-23. This difficult-to-treat patient group stands to benefit greatly from prophylaxis with bypassing agents from a quality-of-life standpoint, especially for the subgroup of patients who are also ineligible for or have failed immune tolerance induction (ITI).

Current literature on FEIBA prophylaxis in paediatric patients is mainly limited to a handful of studies and small case series. FEIBA prophylaxis has been used in conjunction with ITI in patients, in particular as part of the Bonn ITI protocol 24. In a meta-analysis, data for 34 haemophilia patients (adults and paediatric) with inhibitors on a FEIBA prophylaxis regimen (50–100 IU kg−1, 2–7 times per week) found that all bleeding events were reduced by 63.9% and joint bleeding events reduced by 74%, compared to frequency of bleeds prior to starting FEIBA prophylaxis. The mean age of patients in the study was 10.1 years (3–39 years), and their peak inhibitor titre range was 8–8000 BU 17. In a prospective study of paediatric FEIBA prophylaxis during ITI (n = 22; age 0.1–6 years), Kreuz similarly showed that 50–100 IU kg−1 once or twice per day FEIBA prophylaxis during the period that patients experienced inhibitors >2 BU was effective in preventing joint haemorrhages. The median annual incidence of joint haemorrhage during FEIBA prophylaxis was 1 (0–6) 25. In small case series, FEIBA prophylaxis was documented in seven paediatric patients or less per series and overall orthopaedic status was maintained or improved 16, 19, 20, 26-31. Many of these case series have been reviewed more extensively 32 and are outlined in Table 1.

| Study | n | Age (years) | Regimen | Bleeding outcome | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kreuz et al. 25. | 22 | 0.1–6 | 50–100 IU kg−1 q.d. to b.i.d. | Median annual number of joint bleeds = 1 (range, 0–8) | No AEs, no TEs |

| Leissinger et al. 19 | 5 | 3–16 | 50–75 IU kg−1 t.i.w. and 100 IU kg−1 q.d. | 73–83% reduction in bleeding episodes | No AEs, no TEs |

| Valentino 30 | 1 | 9 | 75 IU kg−1 q.3.d | 95% reduction bleeding episodes | No AEs, no TEs |

| Saxena et al. 31. | 4 | 7–13 | 46–100 IU kg−1 q.d. | Significant reduction bleeding episodes | 2/4 patients initial anamnestic response, stabilized |

| Valentino 16 | 5a | 3.7–24.1 | 100 IU kg−1 q.d. | 84% mean reduction bleeding episodes | 1 allergic reactionb, no TEs |

| Hilgartner et al. 26. | 7 | 5–10 | 50–100 IU kg−1 q.o.d. or t.i.w. | No changes in joint health | No AEs, no TEs |

| Jimenez-Yuste et al. 28. | 3c | 6–11 | 50 IU kg−1 q.o.d. to t.i.w. | Total bleeding episodes decreased in 4/5 patients | No AEs, 1/3 patient initial anamnestic response, stabilized |

| Ohga et al. 20. | 1 | 14 | 50 IU kg−1 t.i.w. | No bleeding events | No AEs, no TEs |

- a There was an additional patient in the study with haemophilia B for a total of six patients.

- b The allergic reaction was one episode in one patient and related to one batch of product 32.

- c There were two non-paediatric patients in the study who were not included in this table.

- AE, adverse event; TE, thrombotic event; t.i.w., three times per week; q.d., every day; q.o.d., every other day; b.i.d., twice per day; q.3.d, every 3 days.

The first prospective, randomized, crossover study (Pro-FEIBA Study) comparing 6 months of FEIBA prophylaxis three times per week with 6 months of on-demand therapy in 26 patients (age 2.8–62.8; median 28.7) demonstrated decreased frequency of joint (reduction by 61%; reduction of target joints by 72%) and other bleeding events in patients with severe haemophilia A and FVIII inhibitors 33. A recent phase III, prospective, randomized, two-arm parallel study (FEIBA PROOF) corroborated evidence for efficacy and safety of FEIBA prophylaxis in haemophilia A and B patients with inhibitors 34. In 36 patients studied for over a 12-month period, treatment with a FEIBA prophylactic regimen showed a 72% reduction in median annual bleeding rate (ABR) compared to on-demand treatment. While the Pro-FEIBA and FEIBA PROOF studies provided important information on the significant reduction of bleeds in adolescent and adult inhibitor patients, there remain large gaps in knowledge and systematic alignment of FEIBA prophylaxis treatment practices, in particular with the paediatric population. This study aims to examine the effect of FEIBA prophylaxis specifically in children, and empirically define paediatric FEIBA prophylaxis protocols targeted at preventing haemarthroses and subsequent joint damage in severe haemophilia A paediatric patients with FVIII inhibitors.

Materials and methods

This report combines overall clinical experience in FEIBA long-term prophylaxis in children with severe haemophilia A and inhibitors from two haemophilia treatment centres, one in the US and the other in Germany. This study was a retrospective chart review and patients were selected based on the following definitions.

Patient inclusion criteria

Severe (FVIII < 1%) haemophilia A patients younger than 13 years old at start of the study, who developed high-titre inhibitors (>5 BU) to FVIII were enrolled. Patients could not be currently undergoing ITI but could have a history of utilizing an ITI regimen. Patients were required to be adherent to prophylaxis with FEIBA. Adherence to prophylaxis was assessed by reviewing treatment logs and tracking the frequency of FEIBA prescription refills in comparison with prescribed regimen. A patient was considered fully adherent if >90% of their prescribed prophylactic regimen was administered.

Data collection

The number of joint bleeds per patient was captured by reviewing patient treatment logs/patient diaries at the time of their visits and/or by their parent/caregiver's reports. The number of school days missed (days of inactivity due to a bleed) was reported at the time of the patients’ visits by their parent/caregiver and/or were captured from the patient diaries. Physical activity level was documented during routine patient visits. Joint status for each patient was assessed at the time of comprehensive annual evaluations using a modified Petrini score 35, 36. The patient medical records were documented electronically and the study reviewed the electronic database.

After the initiation of FEIBA prophylaxis, inhibitor titres were obtained at 4–6 weeks and every 3 months thereafter. The definition of anamnesis in the German centre was the rise of inhibitor titre >20% above baseline. The definition of anamnesis in the US centre was >2 times baseline titre.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were performed and continuous variables were expressed using univariate analysis. Comparisons were analysed using chi-squared tests for statistically significant differences.

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 16 children (seven patients from US and nine patients from Germany) and preadolescents aged <13 years were studied for FEIBA prophylaxis usage and joint outcome. Mean age of subjects at the start of FEIBA prophylaxis was 7.5 ± 3.6 years (median = 7.6 [1.5–12.8]). The mean age at the last evaluation included in this report was 17.6 ± 5 years (median = 19.2 [7.3–24]). The median duration of FEIBA prophylaxis evaluated was 9 years (2.6–20.5). All but one patient had a history of ITI; the remaining patient was not a suitable candidate for ITI. The median baseline inhibitor titre before the start of FEIBA prophylaxis was 23 BU (3.1–170) and the median historical peak titre was 240 BU (80–8000). Although not all patients had a high baseline inhibitor titre just prior to the start of FEIBA prophylaxis, all patients had historical peak titres that were high and thus considered to be high responding or high-titre inhibitor patients. Patient characteristics are described in Table 2.

| US | Germany | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age at baseline in years mean ± SD median (range) |

8.6 ± 3.2 | 6.6 ± 3.8 | 7.5 ± 3.6 |

| 9.8 (4.4–12.8) | 6 (1.5–11.8) | 7.6 (1.5–12.8) | |

|

Age at last evaluation mean ± SD median (range) |

16.7 ± 5.2 | 18.4 ± 5 | 17.6 ± 5 |

| 19 (9.2–21.5) | 19.2 (7.3–24) | 19.2 (7.3–24) | |

| Starting dose in IU kg−1 | 75 ± 10% | 70–100 | 70–100 |

| Starting frequency | t.i.w. | q.o.d. or q.d. | t.i.w.–q.d. |

| Ongoing prophylaxis | 7 out of 7 | 6 out of 9 | 13 out of 16 |

|

Baseline titre in BU mean ± SD median (range) |

23.8 ± 19.4 | 54 ± 51.9 | 40.8 ± 42.7 |

| 21.8 (3.1–59.2) | 23 (13.3–170) | 23 (3.1–170) | |

|

Historical high titre in BU mean ± SD median (range) |

1585.9 ± 2852.6 | 943.9 ± 1516.4 | 1243.5 ± 2178.8 |

| 344.5 (218–8000) | 210 (80–4500) | 240 (80–8000) | |

| History of ITI | 6 out of 7 | 9 out of 9 | 15 out of 16 |

|

Titre at last evaluation in BU mean ± SD median (range) |

9.7 ± 8.4 | 7.6 ± 10.3 | 8.6 ± 9.2 |

| 12.2 (0.2–21) | 1.5 (0–25.5) | 3.4 (0–25.5) |

- BU, Bethesda units; t.i.w., three times per week; q.d., every day; q.o.d., every other day; b.i.d., twice per day; q.3.d, every 3 days.

A notable difference between the US and German cohorts was the fact that German patients, with the exception of two, started FEIBA prophylaxis immediately after ITI failure, whereas the US cohort were initially treated on-demand with bypassing agents prior to initiating a FEIBA prophylaxis regimen.

Prescribed FEIBA prophylaxis regimen

The prescribed starting regimen for FEIBA prophylaxis was similar in dose between the two centres but varied in frequency (Table 2). The US centre started all patients on 75 IU kg−1 (±10%), three times per week. In the presence of a breakthrough bleeding event, the regimen was modified to daily administration of the same dose for 4 to 6 weeks following the bleed. It is of interest to note that the majority of bleeds that occurred were joint bleeds. The German centre started with a dose of 70–100 IU kg−1 once daily or every other day and then individualized the regimen for each patient according to his individual demands, resulting in doses ranging from 60 to 100 IU kg−1 and frequency ranging from three times per week to twice a day. Prophylaxis regimens in the German centre eventually settled to 70–80 IU kg−1, once a day for five of the nine patients on prophylaxis. One German patient was noted to have particularly poor adherence with the prescribed regimen and was often only administering 80 IU kg−1 once per week.

Patient outcome

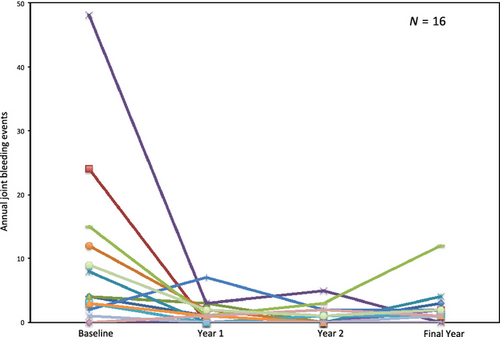

The main outcome to determine the impact of FEIBA prophylaxis in this paediatric patient population was the number of joint bleeds per year in the year before starting prophylaxis compared to the number of joint bleeds on a prophylactic regimen, or the prevention of haemarthroses in children who had not experienced prior joint bleeds (Fig. 1). The mean baseline number of joint bleeds per year among all patients was 8.9 ± 12.7 (median = 4 [0–48]). During the first year of prophylaxis, the mean annual number of joint bleeds dropped significantly to 1.3 ± 1.9 (median = 1 [0–7]; P = 0.0179), representing a reduction of 85.4%. The second year of prophylaxis among the group continued to demonstrate a significant drop in the mean annual joint bleeds compared to baseline at 0.88 ± 1.5 (median = 0 [0–5]; P = 0.0097) joint bleeds, a 32.3% drop from year 1 of prophylaxis. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the first and second year of prophylaxis with respect to the number of joint bleeds (P > 0.3). In the most recent year of evaluation (after a median of 9 years of prophylaxis), these patients showed a mean annual joint bleed rate of 2.1 ± 2.8 (median 1.5 [0–12]). The aforementioned poor adherence to prescribed regimen of one patient resulted in an outlying 12 annual joint bleeds in the most recent year of evaluation, whereas the remaining patients had 0–4 bleeds in the same year. Although this resulted in a slightly higher annual number of joint bleeds among the patient group, there remained a statistically significant lower mean annual joint bleed rate in the most recent year of evaluation compared to baseline (P = 0.0327). The number of joint bleeds in the most recent year of evaluation was not significantly different from years 1 and 2 of prophylaxis (P = 0.358 and P = 0.101 respectively). No life-threatening bleeds occurred during prophylaxis. One patient who discontinued prophylaxis experienced a lethal intra-thoracic haemorrhage 27.

During the year prior to the start of FEIBA prophylaxis, patients from the two centres experienced a mean of 4.6 ± 12.2 (median = 1 [0–48]) non-surgical hospitalizations. Although the mean annual hospitalizations fell in the years after starting a prophylactic regimen (means 1.1 ± 1.6, 0.7 ± 1.8 and 0.2 ± 0.4, years 1, 2 and most recent, respectively), the differences compared to the year prior to starting prophylaxis were not statistically significant (P > 0.089). The higher mean number of non-surgical hospitalizations at baseline was artificially inflated by one outlier patient who experienced 48 hospitalizations during that year.

To examine other clinical outcomes among paediatric patients utilizing FEIBA prophylaxis, patient joint status was measured at the start of prophylaxis and at the last evaluation, using a modified Petrini Score, where elbows, knees and ankles’ range of motion, crepitus, flexion contracture, muscle atrophy and gait abnormality were assessed to generate a combined joint score (maximum score 50 points). A higher score indicates greater damage to overall joint health (Table 3). Mean joint status score prior to prophylaxis was 4.9 ± 5.7 (median = 2.5 [0–17]), and was not significantly different from the joint score at the last evaluation (median 9 years later), which was 3.6 ± 3.8 (median = 3 [0–15]; P = 0.077). The number of school days missed per year for both the year before starting FEIBA prophylaxis, and the year of last evaluation was available in only six patients. The other patients did not attend school at the time of evaluation due to young age. Among the patients with data available, the number of school days missed was lower in the year of last evaluation (median = 3.5 [0–30]) compared to the year before prophylaxis (median = 23.5 [2–70]) for five patients, whereas unchanged in one patient. In 15 patients with available physical activity data, 12 were described as active with no restrictions, and three were considered inactive or sedentary, although no restrictions to their activity were set.

| Patient ID | United States | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US1 | US2 | US3 | US4 | US5 | US6 | US7 | |

| Baseline joint status | 6 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Joint status at last evaluationa | 5 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Patient ID | Germany | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | G7 | G8 | G9 | |

| Baseline joint status | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Joint status at last evaluationa | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 8 | 1 |

- a A modified Petrini score was used to determine the joint status, where elbows, knees and ankles’ range of motion, crepitus, flexion contractures, muscle atrophy, and gait abnormality were assessed to generate a combined joint score. A higher score indicates greater joint damage 36.

Safety of FEIBA prophylaxis

Routine evaluation of health showed that no drug-related safety concerns were evident in this group of patients during the time of FEIBA prophylaxis. No viral seroconversions occurred during this period. Furthermore, there were no cases of thrombosis as a result of the prophylactic regimen, and no allergic reactions to FEIBA. Although central venous access (CVA) was used in 10/16 patients (63%), there was a disproportionate number of patients with CVA between the two centres. The US centre utilized CVA in 29% of their paediatric FEIBA prophylaxis patients (2 of 7), whereas the German centre, used CVA in all but one patient (89%). The German cohort included very young children who had failed ITI and had therefore a pre-existing CVA in place. Of the patients with evaluable data, the mean duration of CVA use was 5.9 ± 3.8 (median = 5.5 [0.75–14.3]) years. Seven of the 10 patients had complications resulting from the use of CVA during FEIBA prophylaxis, although none was life threatening. The most frequent complication was infection and/or sepsis, which occurred in all the patients who reported CVA complications, whereas occlusion presented in three patients with CVAs. Removal of the CVA, either by necessity due to complications or by choice once the patient developed adequate venous access through peripheral veins, did not prevent continuation of prophylaxis.

Anamnestic response was seen in 50% of all patients (8/16) and occurred only in the first 1–3 months of prophylaxis. In the US cohort, 71% (5/7) patients experienced anamnesis, compared to 30% (3/9) in the German cohort. Interestingly, anamnestic response was exclusively observed in the patients who switched from an on-demand bypassing therapy regimen to the prophylactic regimen. In the US, all patients reported in the series went from an on-demand regimen to prophylaxis. In the German cohort, none of the ITI patients who underwent FEIBA prophylaxis immediately after the discontinuation of ITI showed anamnestic response, whereas all patients who switched from an on-demand therapy regimen to prophylactic regimen showed anamnestic response. There was no difference in bleeding during the time of anamnestic response, and inhibitor titres went back to baseline or below. For the anamnesis patients with available data, titres were back to baseline within 3–6 months 37.

Continuation of treatment

As of this writing, 13 of the 16 (81%) cases discussed are continuing FEIBA prophylaxis. One of these patients experienced an interruption in the prophylactic regimen during age 11–13 due to non-adherence, but continued prophylaxis thereafter, and two patients halted FEIBA prophylaxis while attempting ITI but later resumed FEIBA prophylaxis after failing ITI. In the US centre, all reported patients were still undergoing prophylaxis. Of the three patients in the German centre who discontinued prophylaxis, one patient moved to another centre and died after the discontinuation of FEIBA prophylaxis 27, one patient discontinued to start a new course of ITI and has not since resumed FEIBA prophylaxis, and one patient refused prophylaxis at the age of 21. The inhibitor titre measurements at the last evaluation of all patients were comparable or lower than at the start of prophylaxis (P = 0.0106). The mean inhibitor titre at the last evaluation was 8.6 ± 9.2 BU (median = 3.4 [0–25.5]).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that FEIBA prophylaxis among children with severe haemophilia A and inhibitors resulted in a statistically significant reduction in annual joint bleed rate. Furthermore, there were no drug-related safety concerns during the study period. Based on the presented chart reviews, long-term FEIBA prophylaxis prevented or reduced the number of joint bleeds and subsequent joint damage in children with haemophilia A and inhibitors to FVIII. Patients with existing joint damage may benefit from secondary FEIBA prophylaxis to retard and further prevent debilitating haemophilic arthropathy. Paediatric patients with persisting FVIII inhibitors are likely to benefit from bypassing agent prophylaxis, whenever feasible.

Previous reports corroborate this study, suggesting that twice daily, daily, or every-other-day prophylactic dosing of FEIBA at doses up to 100 IU kg−1 are safe from development of thrombotic complications, do not significantly increase inhibitor levels (anamnesis) and are efficacious in controlling and preventing bleeding episodes in patients with inhibitors who are not simultaneously undergoing ITI 9, 26, 38, 39. According to the FEIBA product label, a maximum single dose of 100 IU kg−1 body weight and daily dose of 200 IU kg−1 must not be exceeded.

This study has limitations due to its retrospective nature and low patient number. However, the positive outcome over many years seen in the subjects of this review may be of relevance when considering therapeutic strategies aiming at improving the care of paediatric patients with severe haemophilia and inhibitors to FVIII. There is a great need for further studies on FEIBA prophylaxis. There remains a gap in the availability of reliable laboratory methods to monitor FEIBA therapy. For instance, since there are no published data to describe laboratory monitoring of FEIBA prophylaxis, clinical endpoints must be used to judge efficacy of the treatment regimen.

Criteria for determining which candidate would benefit most from FEIBA prophylaxis constitute another knowledge gap. The paediatric cohort described herein demonstrated consistent response to FEIBA prophylaxis. However, there were approximately one-third of adults in the Pro-FEIBA and FEIBA PROOF studies who were considered poor responders to FEIBA prophylaxis. There may be reason to believe that paediatric patients exhibit a better response to prophylaxis; however, further studies would be needed. Specific criteria for determining the ideal candidate for a prophylaxis regimen are not currently available for haemophilic children even in the absence of inhibitors. Prophylaxis in these children, however, has been established as standard of care 40 in countries where this treatment modality is affordable. Also, optimal dosing and criteria for starting or ending prophylaxis remain still unclear 41. Overall, the clinical experience with prophylaxis in inhibitor patients is less extensive compared to haemophilia patients without inhibitors 42.

Despite the available clinical evidence in the literature and physicians’ practices for the use of FEIBA prophylactically, particularly in the paediatric population, certain obstacles still exist. Depending on the medical reimbursement policies, cost may be a barrier to FEIBA prophylaxis adoption, although cost-benefit analyses have not been performed. Patient willingness to comply with a rigorous prophylactic schedule can pose a barrier, although a high level of patient and caregiver education and follow-up by the health care provider could attenuate adherence issues. To begin to tackle these obstacles and determine best practice standards for FEIBA prophylaxis and outcome, more research is needed.

Overall, long-term FEIBA prophylaxis, in children, adolescents and young adults appears feasible, safe and beneficial, as it is associated with a reduction in the number of annual joint haemorrhages, and a favourable impact on outcome measures. The majority of patients described currently remain on prophylaxis, based on their lower annual bleeding rate and positive effect on their quality of life. However, careful consideration of the risks and benefits of FEIBA prophylaxis in children with coexisting thrombophilic risk factors such as obesity, lack of activity and inherited thrombophilia is advised. A thrombotic event would be a criterion for withdrawing from prophylaxis, although otherwise healthy children do not commonly experience this complication. Lack of venous access, lifestyle choices and very rare occurrences of allergic reactions may be other reasons for discontinuing prophylaxis. It is the recommendation of the authors that once prescribed, and found effective, FEIBA prophylaxis should continue indefinitely for paediatric patients with inhibitors, as is the standard in patients without inhibitors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jocelyn Hybiske, Ph.D., an independent consultant paid by Baxter Healthcare, for writing and editorial assistance.

Author contributions

NE and CE-E conceptualized the content and direction of the manuscript. NE, WK and CE-E revised and edited the manuscript as well as provided final approval.

Disclosures

NE has acted as a consultant and received speaker's fees and/or research funding from the following companies: Baxter, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Kedrion, Grifols and Biogen Idec. CE-E has acted as a consultant and received speaker's fees and/or research funding from the following companies: Baxter, Bayer Healthcare, Biotest, CSL Behring, Grifols, Octapharma and Novo Nordisk. WK has acted as a consultant and received speaker's fees and/or research funding from the following companies: Baxter, Bayer Healthcare, Biotest, CSL Behring, Grifols, LFB, Octapharma and Novo Nordisk.