Evaluating Investment in Space Programs: A Case for Theoretical Pluralism

ABSTRACT

A perennial question repeatedly asked since the early Mercury (USA) and Salyut (then Soviet Union) space programs has been variations on the theme of “how can the cost of space exploration be justified?” This question—which in broad terms constitutes the research question considered in this paper—continues to be directed toward space agencies and their governing institutions around the world. As the title of this paper suggests, in addition to the obvious financial implications, the extent to which funds are directed to space programs directly engages with matters of accountability and public policy. We argue that attempts to justify the cost of space programs have typically been framed on the basis of cost-benefit analyses underpinned by rational choice thinking. We underscore the necessity of incorporating alternative theoretical perspectives to achieve a more meaningful evaluation of the value of space programs. The resulting analysis extends to other public policy decisions involving substantial resource allocations.

Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.

(Cameron 1963, 13)

1 Introduction

Space exploration is very expensive. For example, the cost of the Apollo Program, which led to successfully landing a human on the Moon in 1969 was on the order of (US) $141.15 billion (in 2023 dollars)1. The Artemis Program, designed to return humans to the Moon and involving the United States' National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in collaboration with the European Space Agency, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and Canadian Space Agency is expected to cost (US) $93 billion (Harvey and Mann 2022). Looking forward, the cost of a human mission to Mars is estimated to be in excess of (US) $500 billion (Taylor 2010).

In view of the cost necessitated by space programs, the assignment of resources enabling humankind to venture into space has been repeatedly questioned since the beginning of the Space Age in the mid-20th century. Such questioning is appropriate. The justification of expenditures on space exploration is central to and clearly has direct ramifications for public policy, financial accountability, and fiscal management. Such expenditures result from economic decisions seeking to determine the basis upon which scarce resources ‘should’ be allocated amongst competing ends in order to satisfy policy objectives.

Historically, especially after the 1960s Space Race, the means by which such a decision may be reached have consistently been based on a cost-benefit analysis (CBA) of space programs. However, the apparent regularity with which the direction of resources to space exploration is questioned suggests that answers offered to date have been less than convincing. In this paper, our intent is to revisit the vantage point of CBA as a decision-rule for the question of resource allocation, and in so doing, we seek to draw attention to insights that alternative theoretical vantage points can bring to evaluating decisions to allocate resources to space programs. Our aim in this paper in broad terms is threefold. First, to introduce space program evaluation as a topic worthy of research in the public management/accounting sphere by illustrating its relevance in our society; second, to underline the narrowness of the current debate, both academic and not, on space programs, which mainly rely on CBA and arguments grounded primarily in Rational Choice Theory (RCT); and third, to draft a preliminary research agenda on space program evaluation informed by theoretical pluralism.

The current study is by no means unique in advancing the value of adopting alternative theoretical vantage points (or theoretical pluralism) in accounting research. Previous studies have, for example, presented how theoretical pluralism is able to make sense of the intricacies of public sector activity (Jacobs 2012, 2013), pointed to the benefits of using multiple theories to account for and gain insight into the diversity of actors and practices in accounting research (Modell 2015), demonstrated the ways in which theoretical pluralism can advance understanding of multifaceted organizational realities (Hoque et al. 2015), and considered the part played by theoretical pluralism in realizing several lanes for research in the public sector accounting and accountability arena beyond the new public management setting (Steccolini 2019). The current study follows this tradition of such studies, and in considering the specific case of space programs, provides an opportunity to introduce to the literature another public sector setting that might benefit from a broader theoretical consideration. Such insights can also extend to more informed understandings of how to make more effective other (non-space) public policy decisions involving scarce and substantial resource allocations.

In view of the well-documented “research-practice gap” that has existed and continues to exist in the public sector (Grossi et al. 2023; Tucker et al. 2020), the call for theoretical pluralism as a basis upon which space programs might be evaluated is primarily directed at researchers rather than policymakers and practitioners. This is not to suggest that practitioners and policymakers do not find the outcomes of using different theoretical lenses useful. However, they are unlikely to consciously or deliberately engage with “theory,” preferring to prioritize immediate “real-world” problems rather than abstract concepts (van Helden and Northcott 2010), and unlike academic researchers, they are not necessarily trained to do so (McKelvey 2006)2.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we set the context of the study by briefly reviewing the development of space programs from the US Mercury and (then) USSR Salyut programs in the 1950s to what in the third decade of the 21st century has become known as the “New Space Age.” We draw attention to the repeated questioning of investment in space programs over this period. Next, we outline CBA as a typical and traditional approach used in project evaluation. We draw attention to RCT as the theoretical vantage point underpinning a cost-benefit approach, and in particular consider not only the beneficial insights that RCT is able to offer, but also its limitations as an evaluative vantage point. The subsequent section presents alternative theoretical perspectives from which to evaluate investment in space programs, and the use of theoretical pluralism is advanced as a basis not only for the evaluation of space program investment, but also for other policy decisions that require decisions about allocating scarce and substantial resources (public funds) among competing priorities (specific public programs and initiatives). In the final section, we provide the study's theoretical significance, practical importance, limitations, and suggested areas for future research.

2 The New Space Age—A Context for Accountability

2.1 The Space Sector, Past, and Present

Space sector activity first developed in the 1950s and 1960s within the context of what was known as the Space Race, an international competition between the world's two superpowers—the United States and the Soviet Union—to be the first to land someone on the moon. While this space race would be a proxy cold war for technological and political ideological dominance between two contrasting societies, the genesis of the race was grounded in concerns that one nation would maintain military capabilities that matched or exceeded the other nation. Thus, the achievements that both nations accomplished during this rather short period were quite impressive from a technological, engineering, and managerial perspective. Examples included the first to launch a spacecraft into orbit (USSR in 1957) and the moon (USSR in 1959), to send a human in Earth orbit (USSR in 1961) and moon orbit (USA in 1968), and to land a human on the moon (USA in 1969). National space agencies dominated space activity during this period by exerting command and control over all aspects of meeting space-related strategic objectives. In the United States, these activities involved a heavy reliance on government contracting with coordination and oversight responsibilities belonging to NASA (see Cadbury 2006; Kranz 2000; Siddiqi 2003).

After the Space Race concluded in 1969 with the human moon landing, space activity remained primarily under the control of the two world superpowers, but (1) other nations began conducting their own space affairs3, and (2) the tension of international competition had subsided with even cooperation becoming more prevalent as space advances were made. The United States developed the shuttle program in the 1970s, ushering in the Shuttle Era of crewed flights to perform scientific and servicing missions to satellites and space stations from 1981 to 2011. The Soviets/Russians developed and operated the Mir space station from 1986 to 2001. Collectively, the United States, Russia, countries with the European Space Agency (ESA), Canada, and Japan built and helped operate the International Space Station (ISS) from 1998 to today (European Space Agency 2001; Howell 2021; Logsdon 2022).

Beginning in the 2000s and accelerating since the end of the Shuttle Era in 2011, the space sector has experienced a dramatic increase in private entity participation (Weinzierl 2018). Some have dubbed this new era the New Space Age. Components of the new space activity are reminiscent of the historical public-private partnerships that occurred during the 1970s and 1980s, such as NASA contracting to use both Boeing and SpaceX spacecraft for ISS missions (Schierholz 2014). However, stakeholders in the private sector are now increasingly proceeding with their own space strategic objectives, such as SpaceX's plans to eventually travel to Mars (Musk 2018), and with European companies such as Rocket Factory Augsburg (Germany), Skyrora (Scotland), and PLD Space (Spain) ratcheting up plans to garner first-mover advantages in the European space sector by developing the technological and engineering capabilities for orbital rocket launches (Jones 2022). Forecasters are generally optimistic about the space sector's future prospects with the sector's value approaching the trillions of USD by the 2040s (Foust 2018; Sheetz 2017). This optimism endures despite recent macroeconomic factors placing downward pressure on investment opportunities as competition for reduced capital intensifies (BryceTech 2023).

2.2 Using Resources for Space Activities: Question of Accountability

Space operations are complex and expensive. The Apollo and Shuttle programs cost $141.15 billion and around $270 billion (in 2023 USD), respectively (Borenstein 2011; Dreier 2022; Wall 2011). The ISS cost about $135 billion USD (Sheetz 2021). NASA's current Artemis program to land Americans back on the Moon is predicted to approach over $93 billion USD by 2025, resulting in about (as of now) six billion USD over budget and six years beyond its original operational schedule (NASA Office of Inspector General 2023). The above numbers do not even account for future inflation. Of course, all these figures are quite debatable depending on which space projects are assigned which costs (especially with respect to overhead allocations) from a responsibility accounting perspective.

Whether the public or private sector is spending considerable resources on space-related strategic objectives, questions have persisted throughout the decades over whether society (generally speaking) should use resources for space exploration. A number of objections over the years would at least suggest no and invite further scrutiny and debate. Part of establishing this study's context involves documenting the presence of these objections throughout the past sixty years. A sampling of such objections is outlined in Table 1.

| Source | Primary Objector | Credentials | Objection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dubridge (1962, 465) | “Some people” as suggested in Dubridge's speech | Dubridge: President, California Institute of Technology | Other research agencies would receive more money if space program did not exist |

| Goldsen (1963, 7) | “A number of prominent scientists” and “opinion leaders” as suggested in Goldsen's report | Goldsen: Associate Head of the Rand Corporation's Social Science Department; General editor and contributor to Outer Space in World Politics | Funding concerns for non-space educational programs; psychological concerns of humankind losing sense of identity and belonging with rapid technological advances magnified by space exploration |

| Gregory (1970) | Toynbee | Historian | Pay for human necessities instead |

| Scott-Heron (1970) | Scott-Heron | Street poet, jazz musician, scholar, and novelist | Critique of the preoccupation of the United States achieving a moon landing in light of poverty and racial conflicts on Earth |

| Stuhlinger (1970) | Sister Mary Jucunda | A nun who worked among starving natives of Zambia, Africa | How spending billions of dollars on the Apollo Program could be justified while children starved on Earth |

| Buckley (1989) | Buckley | Author, political commentator | Spend excess government revenue on developing domestic energy resources, not going to Mars |

| Sagan (1991) | Sagan | Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences and director of the Laboratory for Planetary Studies at Cornell University; President of the Planetary Society | Many problems to address on Earth before justifying trip to Mars; only international cooperation and contribution may make trip to Mars worth the cost |

| Rukavishnikov (1993) | Rukavishnikov | Cosmonaut in former USSR | Do not need crewed spaceflights; biological and psychological issues of traveling in space |

| Westfahl (1997) | Westfahl | Science fiction scholar | Refutes philosophical arguments that space exploration reflects a fundamental human inclination to explore distant, unknown regions; economic arguments that solutions to Earth problems can be found in space; and defensive arguments that the need to establish a presence in outer space is necessary to defend against planetary disasters. |

| Hanbury-Tenison and Bizony (2017) | Hanbury-Tenison | Explorer; president of a human rights organization | Pay for Earth's environmental management more directly |

| Bharmal (2018) | Bharmal | Google employee; received NASA's Exceptional Public Achievement Medal | Humans would contaminate Mars, robots would explore more effectively anyway, and we should focus on more pressing Earth issues instead |

| Etzioni and Etzioni (2018) | Amitai Etzioni | International relations scholar | Solve Earth issues instead of exploring Mars as a backstop in the event that human activity destroys Earth |

| Neville (2018) | Neville | Biology student perspective | Possible Earth contamination from returning Martian microbes |

| Garver (2019) | Garver | Former deputy NASA administrator | Prioritize climatology research instead |

| Adams (2021) | Adams | Anthropology student perspective | Solve homelessness and food insecurity instead |

| Newsround (2021) | Prince William | Patron of environmental causes | Focus on repairing planet, not finding another place to live |

| deLespinasse (2022) | deLespinasse | Political science and computer science scholar | Launch pollution |

The sources in Table 1 include serious objections from various individuals who may be persuasive in the ongoing societal debate on whether the costs of funding space exploration exceed the benefits. Evidence from the early years of the Space Race notes objectors to space funding, such as the president of the California Institute of Technology referring to “some people” objecting (Dubridge 1962, 465), while the Associate Head of the Rand Corporation's Social Science Department referred to “a number of prominent scientists” and “opinion leaders” objecting (Goldsen 1963, 7). Also, a nun working in Zambia questioned space expenditures while starvation persisted on Earth. This objection was taken seriously enough to warrant a thoughtful response from Ernst Stuhlinger, the associate director of science at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. Acknowledging that achieving higher crop yields from satellite advances would still require distribution systems to cross challenging international borders to reach populations in need, he offered that space missions have fostered and strengthened international collaboration. The potential for improved relations resulting from this cooperation can help alleviate logistical challenges on Earth (Stuhlinger 1970).

To further analyze objections, consider that prominent figures (defined loosely here as those who people may listen to for insight) throughout the decades, such as the historian Toynbee (Gregory 1970), political commentator Buckley (1989), Prince William (Newsround 2021), and CBS News evening anchor Katie Couric (Brooks 2007), could impact public opinion with their cost-benefit related objections to space funding. Public opinion matters greatly in this discussion. For four decades, polling and analysis from respected think tanks consistently indicate Americans are more prone to suggest too much space expenditure has occurred instead of not enough (Wormald 2014). This objection is important because American public opinion has a role in impacting federal appropriations for space exploration due to the United States’ system of governance (Burbach 2019), and indeed, it is reasonable to suggest this dynamic can be extended generally to most Western nation-states. Enough public opinion on a matter in a particular direction would lead to politicians aligning their stance with what they consider to be their constituents’ desires on resource allocations (such as not funding space exploration), leading to both financial and political accountability related to such decisions.

In addition to the diverse range of objections raised in Table 1, renowned individuals within the space sector have also objected to space exploration from a cost-benefit perspective. Examples include the professor of astronomy and space sciences and director of the Laboratory for Planetary Studies at Cornell University (Sagan 1991), a cosmonaut in the former USSR (Rukavishnikov 1993), a Google employee who received NASA's Exceptional Public Achievement Medal (Bharmal 2018), and a former deputy NASA administrator (Garver 2019).

Politicians especially use narrow cost-benefit arguments to scrutinize public funding on space programs (Munévar 2023), with American objectors including former vice president Walter Mondale (Heppenheimer 1999) and senators William Proxmire (Munévar 2023) and Richard Bryan (Pierson 2006). Also, eliminating funding for space exploration programs was analyzed by the United States Congressional Budget Office when tasked with considering options to reduce the government's financial deficit. While reduced human safety risks were given as a benefit to consider in the analysis for eliminating the program, cost savings were specifically mentioned as a benefit, never mind that the entire exercise was motivated by providing options to reduce the federal deficit (Congressional Budget Office 2018).

In Britain, space industry stakeholders advised politicians on the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee to divert space funds to other agencies. This committee of eleven Members of Parliament aimed to ensure that government departments affecting science, engineering, technology, or research based their policies on scientific knowledge. Submissions highlighted a perceived non-competitive space regulatory framework, arguing that the costs of necessary changes outweighed potential benefits (Ambrose 2023).

Many of the opportunity cost arguments shown in Table 1, which generally hold that we can either explore space or pursue social justice aims but not both simultaneously, have persisted in some fashion through the decades. However, as also shown in Table 1, more contemporary critiques of funding space exploration also include a focus on environmental and ecological damage that can occur with launches or with returning contaminants from space missions. In addition to costs, some commentators claim rocket launches should cease because of their carbon dioxide emissions (deLespinasse 2022), and that space expenditures should instead go towards a more direct approach to Earth's environmental management (Hanbury-Tenison and Bizony 2017). The previously mentioned NASA medal winner makes the case to not colonize Mars, suggesting that humans would contaminate the planet (Bharmal 2018). Other prominent objectors to using resources for human space exploration in lieu of addressing environmental issues on Earth include political advisor and international relations scholar Amitai Etzioni (Etzioni and Etzioni 2018), Prince William (Newsround 2021), and even former deputy NASA administrator Lori Garver (Garver 2019).

Objectors sometimes avoid the opportunity cost perspective and simply conclude the simple CBA of investing in human space exploration does not pass muster. Consultant Linda Billings, who works with NASA, stated, “I don't see that NASA is producing any evidence that [human settlement of space] will be for the benefit of humanity” (Scoles 2023, para. 27). Also, despite promising future space economic activity, economists currently struggle to find the financial justification that would allow businesses to engage with and prosper in outer space activities (Scoles 2023).

While we have focused on the objectors up to this point, we should note that justifiers of space exploration expenditures have also historically predominantly used CBA in decisions. However, exceptions exist. For example, during the 1960s Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union, cost concerns took a back seat to ideological competition for justifying space expenditures (see Cadbury 2006; Kranz 2000; Siddiqi 2003). Once the Space Race and Apollo Program concluded and competition diminished, NASA's appropriation decisions were grounded in a more CBA approach. Post-Space Race political support dropped precipitously for NASA, whose appropriation dropped from a peak of 4.4% in 1966 to ranging from about 0.4% to 1.0% after 1975 going forward (Dreier 2024). In other words, the value proposition for enhanced NASA funding has diminished since the Space Race, suggesting a CBA approach to space appropriations.

Two modern exceptions of primarily using CBA approaches to space expenditures relate to Russia and China's respective space programs. Russia's post-Soviet space policies, and the resulting funding to enact them, have revolved around protecting and legitimizing Russia's international stature and seem to be reactionary towards space-related actions and decisions conducted by the United States (Vidal and Privalov 2023). Also, in the past decade, Russia has also prioritized its military space endeavors at the expense of its civilian efforts (Skibba 2023). While this trade-off may indeed have a CBA component to it, militaristic objectives also tend to leave the realm of CBA considerations and run the risk of being funded for political purposes and/or while creating major destabilizing factors for a national or regional economy. China's space program is another example of an agency that deviates from CBA approaches to justifying expenditures. The Chinese government aims to become a superpower in the space arena by 2045. They wish to play a major role in determining how the international community organizes to govern space-related issues while also increasing their military capabilities in space (Nadarajah 2024).

However, ultimately CBA is used by many government agencies globally in justifying their civilian space efforts. For example, modern federal regulations require that NASA justify decisions by CBA (Baum 2009). Also, the European Space Agency contracted for a CBA to be conducted and determine the feasibility of using space-based solar power for energy requirements on Earth. In addition to analyzing costs, benefits were captured from economic, strategic, environmental, and social perspectives, with qualitative information monetized for analysis whenever possible. The consulting firm observed that this CBA approach has been embraced by government entities and investors as a means to evaluate a program or investment option's attractiveness and justify its funding (Frazer-Nash Consultancy 2022). As another example, the exciting projected future of economic progress in commercial space is drawing more investments from quickly developing nations like India, indicating benefits have exceeded costs from their perspective to engage with the modern space economy. India has established a state-owned organization called NewSpace India Limited to bring together and involve various domestic sectors and stakeholders to develop products and provide services for commercial space activities related to satellites and launch vehicle systems (Government of India 2023).

The above discussion does not imply that CBA approaches are the exclusive method for evaluating space expenditures. However, we conclude that cost-benefit considerations have consistently been the primary factor influencing both the objections to and justifications of space exploration expenditures over the years, with only a few exceptions from various stakeholders. We also conclude that CBA approaches seem to be over-relied upon at the expense of other alternate approaches in debates on whether finite resources should be allocated to achieve space-related objectives. Indeed, on a fundamental level, there would be no need for dedicated organizations to consistently lobby government entities for continuous financial support of space exploration, such as the Alliance for Space Development (2022), if there were no substantial objections to overcome from a CBA perspective. Thus, a scholastic inquiry into space expenditure justifications would advance societal discourse involving determining how resources should be allocated. As a result, we will now direct our attention to the theoretical approach underlying the justification of space expenditures.

3 Cost-Benefit Analyses and Rational Choice Theory

CBA is “the most widely used analytic tool in policy analysis” (Bryner 2006, 434). Appealing to practical and intuitive notions that the benefits of decisions should exceed their costs, CBA analyses decision outcomes with respect to the costs and benefits involved. For any given potential decision, if the benefits exceed the costs for an option, then the option typically results in acceptance; if the costs exceed the benefits, then the decision typically results in rejection.

Despite its parsimony and intuitive appeal, however, CBA remains a controversial decision-making paradigm. Critics have expressed caveats on an excessive reliance on the inherent quantitative emphasis of CBA. Such caveats include the loss of consequence as qualitative factors and subjectivity become more prominent in relation to the decision (Ridgway 1956), the typical definition of costs and benefits expressed (often, but not necessarily) in units of money (Sen 2000), a lack of authenticity associated with “measuring” some costs and benefits (Sinden 2004), the emphasis on hard, scientific evidence grounded in financial economics-based accounting over other epistemic communities and alternative methodological vantage points (Maguire and Murphy 2023), and an inclination to portray the decision maker to be one whose actions are unaffected by emotion or habit (Moll and Hoque 2018).

3.1 Rational Choice Theory—The Underpinning of Cost-Benefit Analyses

Many of these qualifications to the value of CBA reflect criticisms of RCT, upon which CBA is predicated (Elster 1986). RCT posits that individuals typically make decisions consciously or subconsciously assessing a specific course of action's value by deducting its perceived costs from its perceived benefits (Monge et al. 2003). Costs are the elements of a decision that have negative value to an individual, whereas benefits are the elements that have positive value (Tucker et al. 2016). The overall value of a specific decision is the difference between perceived costs and perceived benefits. Thus, RCT serves to describe, explain, and also predict decision-making specifically in terms of an analysis of the perceived costs and benefits associated with available alternatives (Tucker et al. 2024). In so doing, the difficulties of choosing among options within a certain context is fundamentally an optimization problem (Moll and Hoque 2018). This optimization problem requires a rational choice of the decision option that would be expected to return the greatest benefit with the least amount of cost (Scott 2000). In this way, RCT implicitly points to the central contribution that can be made by CBA, and one that is predicated on the theoretical perspective founded on RCT.

Generally regarded as one of the foremost paradigms in neoclassical economics (Green 2006), RCT has been used in a variety of disciplinary research, including economics, political science, anthropology, sociology, organization theory, law, criminology, marketing, education, and psychology (Prabha et al. 2007). However, pointing to the limitations of RCT as a decision-making tool in isolation, Moll and Hoque (2018, 13) note, “(management) accounting research explicitly informed by RCT is relatively rare.” This may be partly due to the criticism that “humans are irrational or at least do not function as the economically rational hypothetical beings that populate the world of neoclassical economics” (Williams 2009, 277). This criticism stems from the claim that decision-making often transpires through a reduction of the “complexity of spatial, temporal, or causal relations among choices and outcomes” (Amit and Schoemaker 1993, 41). This simplification is explainable by the recognition that decision making is subject to the cognitive limitations that influence decision making (Cyert and March 1963). Such cognitive limitations principally relate to variances in people's ability to obtain the same data or resources, to use information to assess the data, and while dealing with limits on the human capacity to identify, take in, and process the data (Simon 1991). Thus, making decisions can be considered using a ‘bounded’ rationality in which the ‘best’ choices are not made, but instead acceptable, reasonable options are chosen.

Adopting a view of RCT that recognizes that humans act within a context of this bounded rationality aids in understanding why individuals may make decisions that do not align with what would be expected to be rational decisions given economic assumptions (Chenhall 2003). Individuals, therefore, are rarely fully informed, and constraints, both tangible and intangible, as well as objective and subjective, influence decision choices. Thus, despite its limitations and criticisms, the main tenets that provide the foundation for RCT and the acceptance of decision-making under conditions of bounded rationality yield a meaningful context in which to better understand how one's perception of costs and benefits impacts the ability of decision-makers to direct scarce resources to space programs rather than other competing, worthy options. Rather than “throwing the baby out with the bathwater,” RCT, with its focus on identifying and evaluating both the costs and the benefits associated with decisions to direct resources to space programs, has the propensity to make a particularly beneficial contribution in informing such decisions. Consistent with the aims of this paper, we seek to draw attention to insights that alternative theoretical vantage points can bring to evaluating decisions to allocate resources to space programs—and thus, our concern in the paper surrounds the assessment of decisions relating to expenditure on space programs. Our attention is now directed to a closer look at costs and benefits typically attributed to space programs, and what an RCT framework can offer in decision making.

3.2 Costs and Benefits of Space Programs

As Maguire and Murphy (2023, 499) point out, by including financial, environmental, and social costs as well as overall benefits, CBA seems to be the “most comprehensive of the economic evaluation measures,” not only in view of the flexibility in terms of how to describe costs and benefits, but also in terms of how they are measured (Viscusi and Aldy 2003). As we have noted above, CBA traditionally quantifies cost and benefit outcomes in monetary units, providing a degree of convenience, clarity, and preciseness (Bryner 2006). However, as illustrated in Table 1, despite attempts to assign a monetary value to what are essentially qualitative considerations, not all costs and benefits are amenable to quantification, and non-economic costs and benefits elude quantification. Nevertheless, the absence of quantification of costs and benefits does not invalidate the use of CBA as an evaluative tool (Alaoui and Penta 2022; Boardman et al. 2022). CBA can be employed at a conceptual level, as illustrated in Table 1 (Levine 1992).

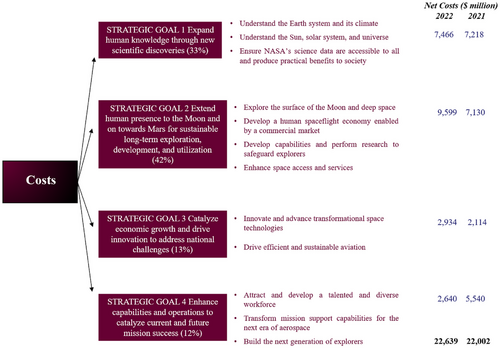

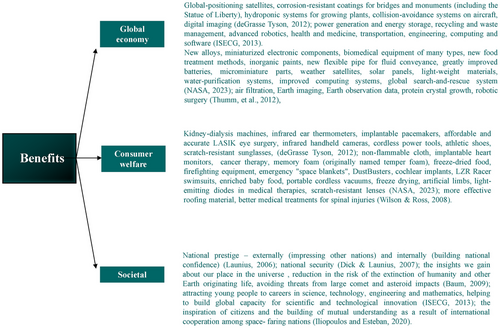

With the above context, Figures 1 and 2 present examples of costs and benefits, respectively, often attributed to space programs.

Figure 1 is a reproduction of costs associated with space programs as reported in the NASA 2022 Financial Year Annual Report (NASA 2022). In this annual report, the net cost of operations during the 2022 fiscal year is presented in terms of NASA's four strategic goals. Thus, Figure 1 represents the taxpayer cost for achieving each agency objective, and in so doing, provides one indication of the range of costs (and typical budget allocations) attributable to space programs. It should be noted that by choosing to direct resources to one specific policy area (space programs), decision makers forego other opportunities to use the same resources in other policy areas (such as health, education, defense, and social security). We emphasize that as the costs presented in Figure 1 are illustrative, and by no means purport to be exhaustive, the cost of space programs portrayed in Figure 1 is likely to be understated as it does not incorporate or attempt to measure how much society might lose in terms of resources and other policy outcomes foregone by directing resources to space programs in preference to other policy areas.

Similarly, Figure 2 represents benefits often cited as resulting from investment in space programs. We classify benefits within three categories—global economy, consumer welfare, and societal—as adapted from the social and economic impact of the Earth observing satellites suggested by Hertzfeld and Williamson (2003). Using this framework, benefits denoted as falling within the category of “global economy” generally relate to impacts on the whole economy through determining variations in GDP, employment, earnings, and similarly informative factors. Benefits assigned to the category “consumer welfare” refer to the impact on consumer welfare through new technology and innovative products, services, and processes that make consumers “better off.” “Societal” benefits are those outcomes that apply to society as a whole, not necessarily relating to a discernible stakeholder or interest group, or outcomes which may be considered to be inherently nebulous or intangible in nature.

Clearly, Figures 1 and 2 are not and do not purport to be exhaustive, nor should they be regarded as the only set of benefits and costs associated with space programs. They do, however, provide an indication of the broad and diverse assortment of costs incurred and benefits resulting as a consequence of space programs, and offer at a minimum five perceptions into the context of any attempt to undertake a CBA of space programs. First, both costs and benefits can be not only of a quantitative/tangible nature, but also qualitative /intangible nature (Iliopoulos and Esteban 2020). Second, benefits are predominantly intangible, whereas costs in general are more instant, more concrete, and less provisional (Bouckaert and Halligan 2006). Third, traditional economic/financial measures do not succeed in fully quantifying benefits, which may unfold over decades or permeate across different areas of influence and relate to different stakeholders with different interests (NASA 2012). Fourth, costs and benefits are interpreted differently with diverse stakeholders, are unlikely to remain static, and the impact on relevant stakeholders may vary in valence and magnitude, rendering any meaningful quantification of them challenging or impractical (Clark et al. 2014). Finally, determining the relative importance/priority of costs and benefits is challenging. Establishing “returns on investment” of the costs and benefits associated with space programs is incommensurable not only because of the absence of a common measure of costs and benefits, but also because the methods of comparison and means of evaluation change (Levine 1992).

These limitations of CBA as applied in the current context do not necessarily render CBA—or RCT as its theoretical underpinning, invalid or unusable. On the contrary, the limitations of CBA and RCT as identified here only serve to reinforce the contention that there are (theoretically speaking), “many roads to Rome,” and CBA within RCT is by no means the exclusive lens through which to scrutinize why funds are directed to space programs in preference to other competing options. The challenges of evaluating the investment in space programs are complex, and amenable to inquiry from different perspectives, thereby presenting an opportunity for the use of different theoretical frameworks to better understand potential explanations. Such an approach is, as outlined earlier, known as theoretical pluralism (Jacobs 2012), and it is towards a consideration of this approach in evaluating investment in space programs that our attention now turns.

4 Beyond Cost-Benefit Analyses—Theoretical Pluralism

4.1 Theoretical Pluralism—An Opportunity to Account for More

Emerging from the preceding discussion, what is apparent is that despite its (arguably) intuitive appeal, parsimony, and comprehensibility, CBA and rational choice theory/thinking possess definite limitations in offering a compelling justification as to why resources from the public purse should be directed towards space programs in preference to other competing ends. Even after allowing for the qualification of bounded rationality, RCT can be criticized for a lack of explanatory and predictive power in explaining the considerable public investment in space programs made by an increasing number of nations. Our position is that other explanations can potentially vindicate the expenditure that has been and continues to be made in this particular domain of public policy. Justifying this position requires we consider other approaches to policy evaluation apart from, and in addition to, merely an identification and calculation of anticipated costs and benefits.

Receptivity to criteria beyond traditionally used cost/benefit principles also carries with it an inherent acceptance that policy evaluation may draw on more than one theoretical frame of reference. As Tucker (2017) observes, different theoretical vantages enable the observer to see what might otherwise be indistinct. More specifically, adopting alternative theoretical perspectives from which to evaluate public policy is desirable because the approach recognizes that no one theoretical avenue can adequately embody the multitude of angles that are typically needed for effective policy analysis of multifaceted matters such as space exploration (Bryner 2006).

Such “theoretical eclecticism,” “theoretical triangulation,” or “theoretical pluralism” is by no means new to accounting and public policy research. Predicated on the perspective that no individual framework exhibits a complete understanding of accounting practices and how organizational policies are executed (Hoque et al. 2015), theoretical pluralism may be thought of as the deployment of different theoretical standpoints concurrently to study a phenomenon by examining the same aspect of a research problem from different perspectives to gain new insights (Hoque et al. 2013). In so doing, theoretical pluralism offers an opportunity to identify salient issues, corroborate key findings, and advance constructions of accounting in practice (De Villiers et al. 2019), thus developing a much richer understanding of accounting thought and practice (Parker 2012).

This study's consideration of using theoretical pluralism for deciding on space sector expenditures is well-grounded in the public sector accounting literature. Notably, Jacobs (2012) discussed and analyzed how theoretical pluralism can be used to better understand complex issues explored in public sector accounting research and encouraged scholars to become more adaptable when choosing the appropriateness of a theoretical perspective to answer research questions (Jacobs 2013). We similarly adopt Jacobs’ stance on the benefits of employing a theoretical pluralistic approach. When adopted in public sector accounting research, combining a plurality of theoretical perspectives has been argued to enhance studies’ descriptive power and strength of their policy significance (Steccolini 2019), and is seen to be particularly necessary in view of the “inherently complex or indeed insoluble (so-called ‘wicked problems’)” characterizing this sector (Lapsley and Miller 2019, 2237). Building on this prior literature, we believe that different theoretical frameworks may provide different insights on the same space sector phenomena under study. The synthesis of insights from a theoretical pluralism approach may provide analyses leading to understandings grounded in the theoretical triangulation of acumens that are gathered via a reconciliation of different theoretical prisms that contain varying emphases.

However, despite its advantages, the task of using multiple theoretical perspectives to evaluate investment in space exploration programs is also likely to present challenges. Arguably, the principal challenge in synthesizing the insights offered by alternate theoretical vantage points lies in researchers attempting to reconcile the unique understandings offered by these alternate theoretical standpoints in terms of their “preferred” theoretical position, to establish which theoretical standpoint is “correct,” why it may be considered to be “correct,” and the ways in which different theoretical insights complement or augment understandings of the rationale underlying the prioritization and investments on these programs (Richardson 2018). A failure to successfully address this challenge may be that the use of theoretical pluralism merely expands the range of our knowledge rather than its depth (Hoque et al. 2013). For the use of different theoretical lenses to provide new insights, researchers might highlight other theories that have been used in other similar contexts, arguing for the need to re-examine the setting from a fresh theoretical standpoint (Jacobs 2012). Each theory comes with its own set of assumptions and biases (Lee and Humphrey 2017), and effective synthesis helps to identify and mitigate these biases by serving to validate and increase the reliability and robustness of conclusions (Hoque et al. 2015), allowing for a broader and more innovative range of explanations and insights that reflect a deeper appreciation of the complexity and multifaceted nature of why decisions to commit to space exploration are made in the light of competing priorities (Jacobs 2012).

Such understandings offer the potential to be more effective compared to a more rigid approach that, perhaps also when influenced by a relativistic philosophy, uses only a single theoretical framework that in actuality is only partially useful in its application to the space expenditure research inquiry. Thus, the theoretical pluralism approach warrants further analysis for evaluating space program expenditures.

4.2 Theoretical Pluralism and Its Contribution to Evaluating Space Programs

In our efforts to evaluate the investment in space programs, our argument to date has been that traditionally, appraisals of space program investment have predominantly been made on the basis of a comparison of the perceived costs and perceived benefits associated with such programs. Although useful, there are limitations to the comparison of costs and benefits due to common concerns with RCT. These concerns are to a large extent grounded in the bounded rationality within which all decision makers operate, as well as the existence of noninstrumental motivations driving expenditure on space programs, such as emotions (Frank 1988), habits (Beckert 1996), and values (Hechter 1994; Friedman et al. 1994). Many of these noninstrumental motivations are grounded in and explainable by the adoption of other theoretical vantage points, leading to our argument that an approach centering on theoretical pluralism from which to determine policy prioritization and assist in making expenditure decisions is likely to offer a more complete understanding of the extent of investment in space programs. This claim begs the question, “what other theoretical stances can offer insights into the justification of investment in space exploration—and what are these insights?”

To respond to this question, we reviewed all papers published in Financial Accountability & Management (FAM) over the period August 2021 to May 2023, and identified the theories most frequently used in these publications4: institutional/neo-institutional theory (e.g., Cordery and Hay 2022; Krishnan 2023; Viana et al. 2022), agency theory (e.g., Garcia-Rodriguez et al. 2021; Haustein and Lorson 2023; Nguyen and Soobaroven 2022), legitimacy theory (e.g., Bisogno et al. 2022; Sofyani et al. 2023; Yasmin and Ghafran 2021), and stakeholder theory (e.g., FitzGibbon 2021; Sofyani et al. 2023). A selection of insights offered by these four theoretical vantage points is presented in Table 2. We stress that theories are helpful in as much they provide insights on specific problems, not because of the frequency with which they are cited in a particular academic journal.5 Clearly, the theories presented in Table 2 are not an exhaustive list of theoretical perspectives that have been used by papers published in FAM, nor do we purport to hold them as “the only” or “the best” theoretical lenses through which investment in space programs may be scrutinized. Rather, they are presented for illustrative purposes as they represent fairly common theoretical standpoints used in FAM and accounting research grounded in public sector and nonprofit sector organizations more generally. As they have appeared in FAM, we assume that these theories will be familiar to and will resonate with many of the FAM readership. Similarly, the insights we offer are by no means meant to be collectively exhaustive. Instead, they reflect some of the considerations drawn from the (respective) theories that may have relevance in understanding evaluations of space programs.

| Theory name | Broad overview | Insight provided |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional theory | “Neo-institutional theory (often just called institutional theory) derives from organizational theory and seeks to explain similarities and differences among organizations, their practices and isomorphic changes to those” (Cordery and Hay 2022, 428). |

|

| Agency theory | “Agency theory (also known as principal-agent theory) describes interactions between at least two parties (i.e., the principal and the agent). Both are linked in a contractual relationship, in which the principal delegates a task to the agent by specifying desired outcomes. The agent acts on behalf of the principal by choosing their own actions, but thereby pursues self-interests” (Haustein and Lorson 2023, 378). |

|

| Legitimacy theory | Legitimacy theory stemmed from the notion of organizational legitimacy, which is defined as, “… a condition or status which exists when an entity's value system is congruent with the value system of the larger social system of which the entity is a part. When a disparity, actual or potential, exists between the two value systems, there is a threat to the entity's legitimacy” (Dowling and Pfeffer 1975, 122). |

|

| Stakeholder theory | “The central idea (of stakeholder theory) is that an organization's success is dependent on how well it manages the relationships with key groups such as customers, employees, suppliers, communities, financiers, and others that can affect the realization of its purpose. The manager's job is to keep the support of all these groups, balancing their interests, while making the organization a place where stakeholder interests can be maximized” (Freeman and Phillips 2002, 333). |

|

By way of illustration, distinct insights can be gained from adopting different theoretical vantage points in explaining investments in space programs. First, it has been extensively documented that a major motivation for both US and Soviet Union involvement in the “Space Race” was to demonstrate their technological and militaristic ascendency in an international landscape defined by the Cold War (Siddiqi 2003; Scott and Leonov 2004; Launius 2004; Grundmanis 2015). Arguably an example of mimetic isomorphism, one question central to the justification of space program investment is the strength of influence of this political motivation. It is likely that answering this question would be informed by recourse to the theoretical position of institutional/neo-institutional theory. Using this framework, for example, political considerations may be more appropriately considered, analyzed, and understood in decisions involving space investment, where one institution mimics using political influences perceived to be successfully used by a competing institution in achieving national space program strategic objectives. This framework would allow for more inclusive consideration of abstract notions such as “military superiority” or “national pride” that (when deemed important) would be difficult to tangibly analyze and account for in decision contexts while using RCT.

Using the same illustration above, the institutional theory framework can additionally be used to further comprehend in what ways the political motivational strength to invest in space exploration withstood calls to instead invest in resolving hunger issues in the late 1960s/early 1970s (Stuhlinger 1970), but then that political strength weakened post-Apollo in the mid-1970s as proxied by NASA budget reductions when the Space Race was no longer a driving force behind space expenditures (The Planetary Society 2023). Again, the institutional theory framework may be helpful in providing a different prism through which to view multiple aspects of space funding decisions.

Second, the assumptions underpinning agency theory are relevant to pursuing public sector accountability in which the citizenry represents principals, and government serves as its agent (Greiling and Spraul 2010). Information asymmetries between agents and principals occur because agents typically possess more details relating to program plans and implementation priorities, as well as challenges (Haustein and Lorson 2023), and in order to ensure accountability, monitoring costs are likely to be incurred by the principal to confirm appropriate agent behavior that advances principal interests. An example of such monitoring costs would be the expenses incurred to audit NASA's Artemis Moon Program by the agency's Inspector General. The audit report released in 2023 found substantial program cost and timetable overruns (NASA Office of Inspector General 2023). This report was delivered to various congressional committees responsible for oversight and appropriations. Representatives elected by the citizenry (principal) can use the audit findings to hold NASA management (agent) to account, which can include adjusting funding for the program if agent behavior is found to be unsatisfactory. In this manner, agency theory can help to better understand how accountability mechanisms influence public space investment decisions.

The agency theory framework can also help to understand and effectively engage with objectors to space investment, such as with respect to environmental objections. For example, environmental groups (serving as a proxy for some citizens, who are the principals) sued the US Federal Aviation Administration (agent) in 2023, alleging that the agency did not sufficiently analyze potential environmental damage caused by a SpaceX rocket launch (Wattles and Nilsen 2023). A better understanding of the principal-agent dynamics involving principals who object to space investment can lead to both better communication and accountability between the citizenry and space agencies with respect to providing funding to achieve space strategic objectives. This important dynamic cannot be ignored in public space policy discourse and would likely not be entirely present with only an RCT approach to funding decisions involving space agencies.

Thirdly, the idea underlying legitimacy theory pertains to the presence of a “social contract” between an entity and the society within which it functions (Deegan 2002). This theoretical perspective suggests that organizations seek to manage societal perceptions of their actions. A range of strategies are available to organizations when they perceive a legitimacy gap exists, including, “correcting their behavior in order to realign it with the desires of society; attempting to change not the behavior itself, but the perception that society has of their behavior; changing the perception that society has of their behavior, manipulating it, deceiving it, or simply distracting its attention; and/or influencing society with the aim of adjusting its expectations” (Archel et al. 2009, 1286). This “management” of legitimacy is important not least because as Jacobs (2012, 6) noted, “…public sector organizations must create, maintain, and manage legitimacy in order to receive continued support and maintain their funding”.

Legitimacy theory may particularly be beneficial in better understanding funding decisions related to space exploration and its related environmental concerns. For example, concerns mount in relation to increased satellite launches and deployment leading to space debris cluttering orbits around and potentially damaging Earth and spacecraft due to collisions. One way to help legitimize space operations and their funding includes actions such as ESA prioritizing providing timely information about space debris amounts, their challenges, and the mitigation efforts needed to reduce their harmful impacts. This transparency can help address debris concerns that, if not adequately addressed for stakeholders, could potentially lead to political consequences such as increased costly regulations that would consequentially reduce available resources needed to achieve other agency objectives (European Space Agency 2022).6 The legitimacy theory framework can help provide deeper insights into justifying sustainability-related space expenditures that may not be completely captured using an RCT approach, all while providing clarity on how such agency actions may help to provide accountability on matters relating to environmental concerns of space exploration.

Finally, stakeholder theory provides a view that posits that in balancing stakeholder interests, entities must decide which stakeholders should be afforded larger importance, value, or precedence (Fassin 2008; Mitchell et al. 1997). Thus, organizations will often need to compromise on meeting the requirements of some stakeholders at the cost of others (Benson and Davidson 2010; Mitchell et al. 2016). This “expense of others” will often include objectors to the proposed action. Many, if not all, objections to space exploration are by definition a result of government space investment decisions placing more value on stakeholders wishing to advance achieving strategic space objectives than on weighting the substance of stakeholders who object to investing in space exploration. Stakeholder theory may be well positioned to better understand these underlying dynamics, as considered in an illustration below.

For example, in 2020, the Michigan Aerospace Manufacturers Association announced plans to eventually develop a spaceport in rural Michigan (US Midwestern region) along Lake Superior (Thompson 2022). There are many public and private stakeholders to consider in this type of space-related activity. From an operations perspective, how will the rocketry and payload supply chain benefit from the spaceport's location? Economically, how will economic development from spaceport activity (both construction and operations of) benefit state and local areas? From an environmental perspective, there are environmental concerns about the project from concerned citizens, such as represented by the Superior Watershed Partnership and the Citizens for a Safe and Clean Lake Superior. For the project to proceed, it will need to receive approval from public stakeholders such as the local government's Planning Commission and the Federal Aviation Administration. How will both the project's proponents and the varying involved government agencies balance claimed economic possibilities with environmental and safety concerns, all involving a variety of stakeholders? How is weighting assigned to competing factors espoused by the various stakeholders when the federal government makes spaceport licensing decisions, and when state and local governments consider allocating grants for development? A desire to understand the dynamics among relevant stakeholders will be generally absent in analyses using the RCT framework yet could be vitally important in further understanding public space investment decisions and any desire to resolve objections to such decisions.

In summary, the four theoretical vantage points outlined in Table 2 not only suggest alternative vantage points from which public policy decisions may be appraised, but also different insights that such vantage points might bring to policy evaluation. As emphasized earlier, the four theoretical stances are not in and of themselves designed to replace or supersede RCT as ‘the best way’ from which public policy might be evaluated. Rather, these (and other) theoretical frames of reference provide different ways of identifying as well as understanding salient public policy considerations. In so doing, they offer complementary insights that recognize that costs and benefits—although important—represent only one important means by which public policy as it relates to space programs may be assessed. Successful integration of a theoretical pluralistic approach when making space policy decisions can help to address and respond to objections made to resources used for space exploration. In return, space programs could be more effectively held to account with enhanced transparency while also meaningfully engaging in public discourse with their citizenry.

4.3 Theoretical Pluralism—More Than Just Evaluating Space Programs

This paper focuses on, analyses, and encourages a theoretical pluralistic approach to decisions involving public space investments due to the increasing attention given to and traction garnered by advances and possibilities attributed to the growing space sector. However, we see no reason why the analyses proposed in this article cannot be externally valid in their application towards all aspects of public policy that require careful consideration of how finite public resources are appropriated and justified accordingly.

Many sectors consistently receive substantial public resources, such as education, healthcare, agriculture, income security programs, and defense (all of which can include massive research and development funding). Of course, each of the above sectors will have its unique stakeholders to consider and objectives to prioritize and accomplish. However, the public policy decisions relating to investing in all these sectors would similarly benefit from an intentional broader view of evaluation. When capturing, recording, and reporting information to be processed for use in decisions, what one sees depends not only on where one looks for relevant information, but also on how the information is viewed. Accounting scholars may be more aware of this better than participants of almost any other discipline, and their inherent skillsets associated with a knowledge of both accountancy and how theoretical frameworks may be used to advance that knowledge can become very useful in aiding public policy decision makers to more effectively and convincingly allocate scarce resources amongst very deserving competing interests.

The role of theory cannot be overstated in its importance to achieve the above goals. CBA, drawn from the theoretical frame of RCT, is helpful but nevertheless incomplete in justifying the considerable investment necessitated by space programs. The use of theoretical pluralism as a means of providing complementary insights to help interpret the meaning of phenomena is not confined to academic research. Features of theoretical pluralism have been documented in a diverse range of contexts relating to policy-makers (Jacobs 2012), practitioners and practice (Grossi et al. 2023), in sites ranging from patient medical care (Sauder et al. 2021), accounting systems (Cooper et al. 1981), cultural heritage (Apostol et al. 2023), and environmental appraisal (Samiolo 2012).

Following this tradition, the current study analyses how approaching a decision from a certain theoretical position conditions what we are looking at, how we look at the information, and how this information informs our understanding. Utilizing different theoretical vantage points will provide different criteria for how decision makers can evaluate resource allocations. The result is that rather than a reliance on what appears to have been a largely narrow economics-based approach (to date) to the justification of expenditure on space programs, a more holistic and broader approach offered by adopting different theoretical vantage points to the question of resource allocation can yield more complete and compelling decision outcomes.

5 Concluding Reflections

When it comes to assessing the value of investment in space programs, we argue for the use of more theory in the form of a pluralistic approach, rather than using less theory that may lead to an incomplete and ineffective analysis of the decision under consideration. At first glance, it may seem obvious that policy decision makers should incorporate multiple perspectives when determining how much the space sector should receive in scarce resources. However, consistent and persistent objections throughout the decades of space activity have revolved around some version of, “Why do we spend so much on space when people are starving?” Historically, it seems that justifications for space investment have subscribed to a predominantly RCT prism using or attempting to use tangible cost and benefit information. While attempting to achieve strategic space objectives by using expenditures on the public's behalf, government officials’ justifications for public space policy decisions have been some combination of not adequate, compelling, understood, and/or accepted by some stakeholders. It would therefore seem that, at a minimum, tangible cost, and benefits are not the only primary considerations when determining the allocation of scarce resources (public money) to competing ends such as starvation, health, and education in all societies that must balance the addressing of such diverse issues.

Thus, to navigate the growing complex space sector and engage its objectors, decision makers will necessarily need to also look at intangible information in areas that are heavily influenced by government policy decisions. We suggest that using an approach grounded in theoretical pluralism, as encouraged in this article, would help alter how policy decisions regarding space investment are currently justified, especially in light of a lack of consensus about this course of action amongst impacted stakeholders. By considering four theoretical vantage points used by papers published in FAM over the past two years, this article illustrates how additional theoretical lenses—in this case, institutional theory, agency theory, legitimacy theory, and stakeholder theory—have the potential to supplement RCT when processing information to make space investment decisions. Insights from these theoretical vantage points suggest a much broader reframing of costs and benefits beyond the economic/financial items typically examined. In addition, adopting diverse theoretical lenses can broaden the spectrum of research questions (see Alewine 2020 for an initial foray into potential space accounting inquiries). While RCT and CBA predominantly focus on funding decisions, other theoretical perspectives raise different questions that may or may not be directly related to funding. Theoretical pluralism inspires research questions such as historically contextualizing space program investments (institutional theory), exploring accountability mechanisms in complex programs (agency theory), investigating the evolution of side initiatives in space programs (legitimacy theory), and understanding issues related to multiple stakeholders (stakeholder theory).

We also posit that analyses involving public space sector investment decisions are externally valid to other major sectors that are substantially influenced by government policy and appropriation decisions, such as education, healthcare, agriculture, income security programs, and defense. However, although this consideration may be omitting important considerations from those sectors that would limit our analysis’ external validity, future research can help explore this paper's suggestions in other major sectors, industries, and public policy areas. Those findings would have major implications for policy and decision making in multiple sectors that receive substantial public finding, and thus touch almost every aspect of society and its governance.

Future research can also build on the foundations established in this paper. For example, according to the ESA, hibernation studies involving humans for extended deep space traveling objectives could be viable within a decade (Pultarova 2023). Future research can help determine how a combination of frameworks (vs. a sole RCT perspective) would impact public funding decisions for such a research request, as well as contribute to the greater societal question of whether such research is reasonable, necessary, and/or ethical. There are many similar topics that would also be fruitful to explore using an approach based on theoretical pluralism.

Institutional theory, agency theory, legitimacy theory, and stakeholder theory are by no means the only theoretical vantage points that might inform the evaluation of investment in space programs. Future research might also consider other theoretical perspectives besides the four suggested in this paper when implementing a theoretical pluralist approach to decision making. It is unlikely that there will be one single framework, or one combination of specific frameworks, that will have universal effectiveness in making sound government policy decisions when appropriating scarce resources. Any specific sector, and any specific strategic objective within that sector may ultimately call for different frameworks to consider when making investment decisions. The perspectives presented in this paper represent an entreaty that offers a critically analyzed argument that can yield more effective decisions in the public domain that involve substantial resources and impact a diverse array of stakeholders with varying objectives. These perspectives also constitute a basis for the development of a research agenda that could be better advanced through a special issue of an academic accounting journal further exploring additional specific contexts and settings within which theoretical pluralism might provide relevant insights.

Acknowledgments

We express our appreciation the suggestions made by Lee Parker, Laurence Ferry, and Zahirul Hoque on previous drafts of this paper, as well as the anonymous reviewers. In addition, we thank attendees of the CWeX Research Seminar UniSA Business, University of South Australia, for their insightful and constructive comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Open access publishing facilitated by University of South Australia, as part of the Wiley - University of South Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.