Topical N-phosphonacetyl-l-aspartate is a dual action candidate for treating non-melanoma skin cancer

Abstract

Each year, 3.3 million Americans are diagnosed with non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) and an additional 40 million individuals undergo treatment of precancerous actinic keratosis lesions. The most effective treatments of NMSC (surgical excision and Mohs surgery) are invasive, expensive and require specialised training. More readily accessible topical therapies currently are 5-fluorouracil (a chemotherapeutic agent) and imiquimod (an immune modulator), but these can have significant side effects which limit their efficacy. Therefore, more effective and accessible treatments are needed for non-melanoma cancers and precancers. Our previous work demonstrated that the small molecule N-phosphonacetyl-L-aspartate (PALA) both inhibits pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis and activates pattern recognition receptor nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2. We propose that topical application of PALA would be an effective NMSC therapy, by combining the chemotherapeutic and immune modulatory features of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod. Daily topical application of PALA to mouse skin was well tolerated and resulted in less irritation, fewer histopathological changes, and less inflammation than caused by either 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod. In an ultraviolet light-induced NMSC mouse model, topical PALA treatment substantially reduced the numbers, areas and grades of tumours, compared to vehicle controls. This anti-neoplastic activity was associated with increased expression of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin and increased recruitment of CD8+ T cells and F4/80+ macrophages to the tumours, demonstrating both immunomodulatory and anti-proliferative effects. These findings indicate that topical PALA is an excellent candidate as an effective alternative to current standard-of-care NMSC therapies.

1 INTRODUCTION

A staggering 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer in their lifetimes.1 Most skin cancers are caused by sun exposure, leading to ultraviolet light (UV)-induced damage.2 Skin cancers are categorised as either melanoma or non-melanoma (NMSCs),3 which are the most common type of cancers overall and arise in the basal, squamous and Merkel cells of the skin.3 Basal cell carcinoma is the most common, with an estimated 5.4 million diagnoses annually in the United States,4 followed by squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the second most common and the most metastatic.3 SCC kills more than twice as many individuals as melanoma, at an estimated rate of 15 000 people per year.5 The majority of SCCs arise from actinic keratoses (AKs), pre-cancerous lesions that affect over 58 million Americans, making AKs one of the most common skin conditions treated by dermatologists.6 The direct treatment cost of NMSCs in the United States is estimated to be $4.8 billion per year, not including additional indirect costs in lost wages.7, 8

Currently, there are a number of FDA-approved therapies for NMSC, each with its own advantages and limitations. The gold standard treatment is surgical removal (e.g. Mohs surgery). For precancers (AKs), a regular treatment is cryotherapy. These treatments can be more than 90% effective for individual lesions. However, a major issue not addressed by the localised destructive methods (surgery or cryosurgery) is the fact that most AK lesions arise within a large area of skin that has been damaged by chronic sun exposure and is therefore full of pre-neoplastic cells, a phenomenon called ‘field cancerization’. To address the high statistical risk of cancer arising within these regions, several non-invasive topical treatments are currently approved, including fluorouracil (5-FU; an antimetabolite), imiquimod (IMQ; an immunomodulator), and tirbanibulin (a microtubule inhibitor). All three topical treatments are FDA-approved for AK and have reported response rates of 40%–80% for AKs, with 5-FU being most effective.9 5-FU and IMQ are also FDA-approved to treat superficial BCC, and studies have shown therapeutic effects when applied to the treatment of superficial SCC.10 Although each of these topical agents can treat multiple, diffuse lesions (thereby addressing the ‘field cancerization’ problem) and often result in an overall higher rate of long-term clearance than cryotherapy, each is also associated with an intense local skin reaction characterised by pain, burning, skin erosions and, in some instances, hyper- or hypo-pigmentation of the skin. Therefore, there is still a need for improved topical NMSC therapies that are highly effective yet associated with fewer side effects than the currently available options.

N-phosphonacetyl-l-aspartate (PALA) is a potent and highly specific inhibitor of the multi-enzyme protein carbamyl phosphate synthetase II/aspartate transcarbamylase/dihydroorotase (CAD), which catalyses the first three steps of de novo pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis. PALA was designed as a transition-state analogue inhibitor of aspartate transcarbamylase, and has nanomolar potency.11 It is readily taken up by cells in culture and kills them efficiently by starving them for pyrimidine nucleotides, as aspartate transcarbamylase is required for this de novo biosynthetic pathway. PALA is quite specific, since the salvage pyrimidine precursor uridine completely prevents its toxicity. Systemic administration of PALA showed great anti-neoplastic efficacy as a single agent in murine B16 melanoma and Lewis lung carcinoma tumour models, but clinical trials of PALA as a systemically administered single agent in humans for colon cancer, breast cancer, malignant melanoma or advanced soft-tissue sarcoma were disappointing due to limited efficacy,12 perhaps, at least in part, because of reversal of pyrimidine synthesis inhibition by dietary uridine. However, a great deal of information on the pharmacology and toxicology of PALA obtained during these trials can be leveraged in other clinical applications of this small molecule.12

Recently, an additional role for PALA as an immune modulator of innate immune responses mediated by nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) was discovered.13 NOD2 is an intracellular sensor of a broad range of intracellular and extracellular bacterial pathogens,14-16 as well as a more limited range of viruses.17, 18 It is expressed in both immune cells and barrier cells of the skin,19 where it plays critical roles in cutaneous defence against pathogens.16, 20 CAD, the enzymatic target of PALA, was identified as a negative regulator of NOD2-dependent signal transduction and anti-bacterial activity by analysing candidate NOD2-interacting proteins identified in an immunoprecipitation-coupled, LC–MS/MS analysis of activated cells.13 Depletion of CAD expression using RNAi or treatment with PALA increased NOD2-dependent signalling and enhanced its anti-microbial function.13 Importantly, topical application of PALA to human skin explants and wounded mouse skin resulted in NOD2-dependent upregulation of antimicrobial peptides, recruitment of immune cells to the treated area, and increased clearance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection.21 These findings indicate that PALA can be used topically to modulate innate immune responses of the skin in both mice and humans.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Reagents

PALA (NSC-224131) was obtained from the National Cancer Institute (NCI)/Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD)/Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) Open Chemical Repository (http://dtp.cancer.org). PALA was dissolved at concentrations of 1%, 2% or 5% (w/v) in 50% acetone/10% glycerol (Fisher Scientific). Aquaphor Healing Ointment was purchased from Beiersdorf. Imiquimod Cream (Aldara, 5%; NDC# 45802–368-62) was purchased from Perrigo Company. Fluorouracil Cream USP (Efudex, 5%, NDC# 51672–4118-6) was purchased from Taro Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.

2.2 UVB-induced NMSC mouse model

Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cleveland Clinic (IACUC protocol# 2018–2096) and performed in accordance with relevant institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Anaesthetised female SKH1-Elite mice (Crl:SKH1-Hrhr, strain code 477, Charles River Laboratories) were exposed to UVB thrice a week for 20 weeks as previously described.22 The head and tail regions were masked with felt during UVB exposure to limit tumour induction to only dorsal skin. A custom UV lamp unit equipped with ten 7.2 W G8T5 bulbs (305 nm peak wavelength) with an average irradiance between 0.312 and 0.356 mW/cm2 (USHIO America, Inc.) was used for UVB exposure. The UVB irradiance was measured prior to each exposure session using a PMA2100 radiometer equipped with UVA and UVB detectors (Solar Light) and the time required to achieve the desired dose calculated. Dose of UVB was gradually increased (10% per week) over the first 10 weeks starting at 80 mJ/cm2 dose to a final dose of 175 mJ/cm2 (time range of 8 min 11 s–9 min 20s, depending on UVB irradiance measurements).

After 20 weeks of UVB exposure, mice were divided based on initial number of tumours into treatment groups to balance the initial tumour burden. Mice were treated daily with 200 μL of drug, topically applied to dorsal skin for 10 weeks. Mice were co-housed in small groups (n = 5/cage) and oral exposure of the drug was minimised by the use of a rapidly absorbed vehicle (50% acetone/10% glycerol). At weekly intervals, the mice were weighed and their body condition score was assessed. Tumour burdens were determined weekly from in-person counts and digital photographs quantitated by using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).23 Individual tumours were numbered and tracked during image analysis; in the case that tumour boundaries between individual tumours became confluent (e.g. two tumours merge), it was still counted as two tumours and the area averaged.

At harvest, colon lengths were measured and blood collected in K2-EDTA microtainers (Becton Dickinson) then processed into plasma for serum amyloid A (SAA) measurement by ELISA. All skin lesions were counted at harvest and tumours large enough to be bisected were collected. Tumour tissues were bisected and half was fixed in Histochoice, and embedded in paraffin blocks, and the other half was frozen for ELISA analysis. Tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin/eosin for histopathologic assessment or underwent multiplex immunofluorescent imaging. Skin collected from the mice with UV-induced tumours was carefully selected to bisect the largest tumours for staining. In cases where the mice had several tumours, not every tumour or lesion could be excised. Therefore, we prioritised larger, more pronounced tumours in all the mice and examined as many tumours as possible. The tissues examined by the resident dermatologist were not representative of the whole sample and some smaller precancerous lesions were excluded; however, this was a consistent practicse among all treatment groups.

2.3 Skin irritation testing

The topical formulations of 2% PALA/50% acetone/10% glycerol, 5% imiquimod (IMQ), 5% 5-FU (5-FU), vehicle control, and Aquaphor were applied (~0.05 g/mouse) daily to the dorsal skin of SKH1-Elite female mice (8 weeks of age; n = 5/group) for 7 days. The Aquaphor and vehicle treated groups were combined during final analyses into a single group, as there were no differences detected between these groups. Mice were monitored daily for weight change, skin appearance and signs of distress. In response to significant weight loss in the IMQ and 5-FU treatment groups, these mice were supplemented with Diet Gel 76A (ClearH2O) starting on Day 3 (IMQ) or Day 5 (5-FU). At harvest, spleen weights and colon lengths were measured. Blood was collected in K2-EDTA microtainers (Becton Dickinson) and processed into plasma for SAA measurement by ELISA. Skin tissue was harvested and either fixed in Histochoice and embedded in paraffin blocks, or frozen for ELISA analysis. Tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin/eosin for histopathologic assessment.

2.4 Enzyme-linked immunoassays

Serum amyloid A levels were measured in plasma samples using the Mouse SAA ELISA kit (E-90SAA, Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc.) according to manufacturer's instructions. Lipocalin-2 (LCN2) was quantified from pre-weighed stool samples homogenised in 0.5 mL PBS using the Mouse Lipocalin-2/NGAL DuoSet ELISA (DY1857) and DuoSet Ancillary Reagent Kit 2 (DY008, R&D Systems). Skin protein lysates were made by homogenising frozen tissue with a pestle and scissors in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate, 1x Pierce protease inhibitor cocktail [A32965, ThermoFisher]). Cytokines and chemokines were quantified from 25 μg of lysate using a custom 10-plex U-PLEX panel (K15069L-2; Meso Scale Discovery) that included: GM-CSF, KC/CXCL1, IFNα, IFNβ, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17F, IP-10/CXCL10, MCP-1/CCL2, RANTES/CCL5 and TNFα. The MESO SECTOR S 600 plate reader (IC0AA-0; Meso Scale Discovery) was used to collect the U-Plex data and data were analysed using MSD Discovery Workbench 4.0 software.

2.5 Multiplex immunofluorescent imaging

Immunohistochemistry staining was performed using the Discovery ULTRA automated stainer from Roche Diagnostics. In brief, antigen retrieval was performed using Proteinase K (IHC Select, 21 627; Millipore) and/or a Tris/Borate/EDTA buffer (Discovery CC1, 06414575001; Roche), pH 8.0 to 8.5. Antigens were denatured using a citrate buffer (Discovery CC2, 05424542001; Roche). Time, temperatures and dilutions are listed in Tables S1–S3. The antibodies were visualised using the OmniMap anti-Rabbit HRP (05269679001; Roche), and UltraMap anti-Rat HRP (05891884001; Roche) in conjunction with the Akoya Biosciences (Marlborough, MA) Opal Fluorophores, listed with their respective antibodies (Tables S1–S3). The slides were counterstained with Spectral DAPI (FP1490; Akoya Biosciences).

For cell secreted molecules (e.g. DefB14), the areas of positive staining within tumour tissue were measured using QPath software. First, the total tissue area was assessed (both tumour and non-tumour) using a ‘tissue detection’ command. Next, a thresholder command was used to determine the amount of specific fluorophore detected within the region. A percentage of area covered by the targeted fluorophore was calculated for each sample.

Within the same annotation of tissue regions, the proportion and densities of LL37+ cells, CD3+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, F4/80+ macrophages and MPO+ cells were assessed using a positive cell detection method on the QuPath software. This allows for a thresholder function to be used to determine cellular radius and fluorophore detection threshold. DAPI or an auto-fluorescent detection channel were used to determine total number of cells in the tumour region. A percentage of positive cells for each targeted fluorophore was calculated for each detection channel.

2.6 Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the Discovery ULTRA automated stainer from Roche Diagnostics by the Cleveland Clinic Imaging Core. In brief, antigen retrieval was performed using a Tris/borate/EDTA buffer (Discovery CC1, #06414575001, Roche), pH 8.0–8.5. Time, temperatures and dilutions are found in Table S4. The antibodies were visualised using the OmniMap anti-rabbit HRP (#05269679001, Roche) in conjunction with the ChromoMap DAB detection kit (#05266645001, Roche). Lastly, the slides were counterstained with haematoxylin and bluing.

2.7 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed on GraphPad Prism software (Version 9.1). One-way or two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Bonferroni or Tukey's multiple comparison test was used to determine significance of datasets with multiple variables. Chi-squared test was applied for categorical variable comparisons. Details of tests used for specific experiments have been included in the figure legends.

3 RESULTS

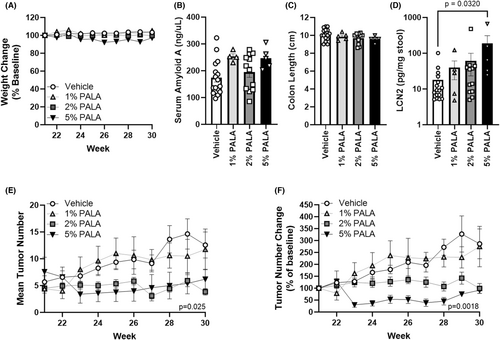

3.1 Topical PALA is not toxic up to 5% (w/v) and reduces tumour growth in a dose-dependent manner

To determine an optimal dose of topical PALA for treatment of NMSC, SKH1-Elite mice were UV-irradiated thrice a week for 20 weeks to induce SCCs and then treated daily for 10 weeks with 0%, 1%, 2% or 5% (w/v) PALA in 50% acetone/10% glycerol. Topical PALA treatment was well tolerated over 10 weeks, with no apparent skin irritation or weight loss (Figure 1A). Previous toxicology studies identified the intestine, liver and central nervous system as the first targets of systemic PALA toxicity12; therefore, circulating levels of SAA were measured from plasma collected at endpoint as a marker of liver inflammation and systemic toxicity (Figure 1B). No significant differences were found between treatment groups; however, there were trends of higher SAA levels in the 1% and 5% PALA-treated mice (p = 0.067 and p = 0.066, respectively). Colons were examined for gross pathology and colon lengths were measured at harvest as a quantitative measure of intestinal pathology. None of the mice had any apparent gross colon pathology or significant differences in colon lengths between treatment groups (Figure 1C). Levels of faecal lipocalin-2 (LCN2) were also quantified as a marker of intestinal inflammation. Only mice treated with 5% PALA had significantly higher LCN2 levels as compared to vehicle treated mice (186.8 ± 121.1 vs. 18.1 ± 6.0, p = 0.032; Figure 1D). Importantly, mice treated with 2% or 5% PALA had substantially fewer total tumours (3.83 ± 0.6 and 6.20 ± 1.8, respectively at endpoint) over the 10-week treatment period than those treated with either vehicle or 1% PALA (12.5 ± 2.4 and 11.7 ± 3.8, respectively at endpoint, p = 0.029; Figure 1D). This was especially apparent when the average change from initial tumour burden was calculated; the vehicle- and 1% PALA-treated groups showed steady increases in average tumour burden (286.4% ± 62.6 and 275.0% ± 84.7 of original size at endpoint, respectively) that was not observed in the 5% PALA group (91.6% ± 13.4 of original size at endpoint) as early as 3 weeks of treatment and by 8 weeks of treatment for the 2% PALA group (99.2% ± 20.5 of original size at endpoint, p = 0.0018; Figure 1E). These results indicate that topical PALA is well tolerated up to 5% (w/v) over 10 weeks of daily treatment and demonstrate anti-tumour activity at concentrations of 2% and higher. The dose of 2% PALA was selected for further analysis, based on a significant anti-neoplastic effect (mean tumour burden change of 286.4% ± 62.6 in vehicle vs. 99.2% ± 20.5 of original size for 2% PALA at endpoint, p = 0.0018) and the absence of any elevation of the inflammatory markers SAA and LCN2 at this dose.

3.2 Daily application of topical PALA is better tolerated than NMSC standard-of-care topical treatments

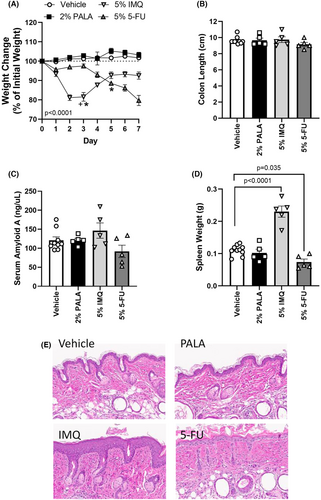

The tolerability of daily treatment with the current standard of care topical ointments, 5% IMQ and 5% 5-FU were compared to 2% PALA on naïve SKH1-Elite mice, as well as their vehicle controls, over 7 days. Skin appearance, weight change and body condition score were assessed daily. In contrast to vehicle and 2% PALA treated mice, significant weight loss was observed in mice treated topically with either IMQ or 5-FU, requiring interventional care and resulting in one death (Figure 2A, arrows). Skin irritation was apparent on IMQ treated mice as early as Day 2 and Day 5 in the 5-FU group; no skin irritation was seen in either vehicle or 2% PALA treated mice (Figure S1).

Upon harvest on Day 7, gross pathology of the spleen and intestine were assessed, SAA levels measured, as well as skin histopathology and expression of inflammatory mediators in treated skin evaluated. No differences in gross intestinal pathology or SAA levels were observed among groups (Figure 2B,C). Similar to previous reports of topical IMQ treatment of mice,24 mice treated with IMQ had splenomegaly (Figure 2D), overt thickening of the epidermis (acanthosis; Figure 2E), and upregulation of IL-17 family cytokines in the treated skin tissue (Table 1). In addition, cutaneous levels of RANTES and GM-CSF were elevated in IMQ treated animals (Table 1). 5-FU-treated mice also demonstrated toxicity characterised by significant decreases in spleen weight (Figure 2D), epithelial erosion (Figure 2E), and increased expression of IL-6, IL-17C, KC and GM-CSF in treated skin lysates (Table 1). In contrast, PALA-treated mice had no changes in spleen weight, colon length, SAA levels, skin histology or expression of an inflammatory cytokine/chemokine panel in treated skin as compared to vehicle controls. These findings indicate that daily application of topical PALA to mice is much better tolerated than current standard of care topical treatments for NMSC.

| Cytokine/chemokine | Vehicle mean (SEM) | 2% PALA mean (SEM) | 5% IMQ Mean (SEM) | 5% 5-FU mean (SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 25.4 (3.2) | 38.8 (8.1) | 61.3 (10.0) |

268.8 (104.8) p = 0.0131 |

| IL-17A | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.09) |

1.6 (0.1) p = 0.0177 |

1.2 (0.4) |

| IL-17C | 0.5 (0.03) | 0.6 (0.1) |

1.0 (0.04) p = 0.0122 |

1.4 (0.1) p < 0.0001 |

| KC | 26.3 (6.4) | 31.1 (2.8) | 28.6 (5.9) |

114.5 (16.4) p = <0.0001 |

| RANTES | 43.7 (3.2) | 46.4 (9.6) |

141.0 (36.1) p = 0.0061 |

17.7 (5.0) |

| GM-CSF | 0.8 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) |

2.5 (0.7) p = 0.0265 |

2.6 (0.2) p = 0.0188 |

- Note: Significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test, n = 5/group. The following cytokines and chemokines were profiled but not differentially expressed: TNFα, IFNα, IFNβ, IL-1β, IL-12p70, IL-17F, MCP-1 and IP-10.

- The bold values are the p values for significantly different values in the table.

- Abbreviations: PALA, N-phosphonacetyl-L-aspartate; IMQ, imiquimod.

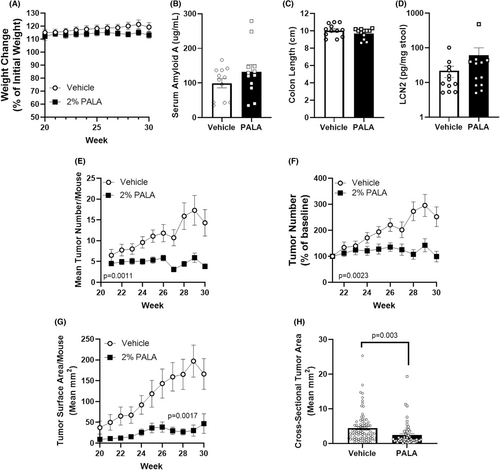

3.3 Tumour burden, tumour area and tumour grade are reduced in mice treated with topical PALA

AK lesions and SCC tumours were induced on SKH1-Elite mice through exposure to UVB over 20 weeks. Tumour bearing mice were treated daily with either 2% PALA or vehicle control daily for 10 weeks and evaluated for toxic side effects of treatment, as well as for treatment-induced changes in tumour number, size and grade. Daily treatment of mice with topical PALA for 10 weeks was well tolerated as reflected by no significant differences in weight, SAA levels, gross intestinal pathology or LCN2 levels as compared to vehicle-treated control mice (Figure 3A–D). PALA-treated mice had a significantly lower tumour burden than vehicle-treated mice; the average number of tumours on vehicle-treated mice increased over the 10-week treatment period (endpoint value of 252.3% ±34.3, p = 0.00051), while the average tumour number per mouse in the PALA-treated group remained constant (endpoint value of 99.2% ± 20.5, p = 0.97) (Figure 3E,F). Tumour sizes were also dramatically larger in the vehicle-treated group, both for mean surface tumour area (endpoint values of 197.1 mm2 vs. 30.3 mm2; p < 0.0001) and for mean tumour cross-sectional area (endpoint values of 4.4 mm2 vs. 2.4 mm2; p = 0.003) (Figure 3G,H). When the growth of individual tumours were analysed, a greater proportion of PALA treated tumours resolved over the treatment period than vehicle controls (83.3% vs. 26.8%, respectively, p < 0.0001; Table 2). Additionally, the growth phenotype was distinct between the treatments, with most of the PALA treated tumours shrinking after an initial period of growth or continually reducing in size (97.9%) versus the continual growth observed in the vehicle treated animals (46.3%; p < 0.0001; Table 2). These data support the potential use of topical PALA for the treatment of both AK and SCC lesions.

| Vehiclea (n = 41) | PALAa (n = 48) | p-Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour growth outcome | Larger | 24 (58.5%) | 6 (12.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Same | 3 (7.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Smaller | 3 (7.3%) | 2 (4.1%) | ||

| Resolved | 11 (26.8%) | 40 (83.3%) | ||

| Tumour growth phenotype | Continual growth | 19 (46.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Grow then shrink | 12 (29.2%) | 33 (68.7%) | ||

| No change | 3 (7.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Continual shrinkage | 7 (17.0%) | 14 (29.1%) | ||

- Note: The bold values are the p values for significantly different values in the table.

- Abbreviations: PALA, N-phosphonacetyl-L-aspartate.

- a Data presented as N (%);

- b Based on chi-squared test for categorical variables comparisons.

Excised tumours were histologically graded as either benign/hyperplastic lesions, AK/SCC in situ, well differentiated SCC, or poorly differentiated SCC (Table 3). Importantly, in comparison to vehicle-treated controls, PALA-treated mice had a lower prevalence of well differentiated SCC and poorly differentiated SCC (38% vs. 69%, p < 0.0001) and an increased proportion of AK/SCC in situ and benign lesions (62% vs. 31%, p < 0.001), indicating that PALA treatment can block tumour progression.

| Characteristicsa | Tumour grade | Vehicle | PALA | p-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total tumour number | Poorly differentiated SCC | 25 | 6 | 0.0002 |

| Well differentiated SCC | 37 | 12 | ||

| AK/SCC in situ | 28 | 23 | ||

| Benign/hyperplastic | 0 | 6 | ||

| Tumours/mouse | Poorly differentiated SCC | 2.0 (1.6) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.0002 |

| Well differentiated SCC | 3.0 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.1) | ||

| AK/SCC in situ | 2.3 (2.1) | 1.9 (1.2) | ||

| Benign/Hyperplastic | 0 (0) | 0.5 (0.6) | ||

| Tumour prevalence | Poorly differentiated SCC | 28% | 13% | <0.0001 |

| Well differentiated SCC | 41% | 25% | ||

| AK/SCC in situ | 31% | 49% | ||

| Benign/Hyperplastic | 0% | 13% | ||

| Tumour area | Poorly differentiated SCC | 59.5 (77.3) | 62.6 (70.0) | 0.88 |

| Well differentiated SCC | 10.7 (18.0) | 7.5 (4.5) | ||

| AK/SCC in situ | 3.4 (6.6) | 2.3 (2.0) | ||

| Benign/Hyperplastic | 0 (0) | 1.4 (0.3) | ||

| Tumour cross sectional area (mm2) | Poorly differentiated SCC | 9.2 (5.8) | 9.8 (6.4) | 0.62 |

| Well differentiated SCC | 3.7 (2.0) | 3.1 (2.2) | ||

| AK/SCC in situ | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.1 (1.0) | ||

| Benign/Hyperplastic | n/a | 1.7 (2.0) |

- Note: The bold values are the p values for significantly different values in the table.

- Abbreviations: PALA, N-phosphonacetyl-L-aspartate; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

- a Data presented as mean (SEM);

- b Based on chi-squared test for categorical variables comparisons or 2-way ANOVA.

Excised tumours were also stained for the expression of cell cycle markers to determine whether PALA may be inducing cell cycle arrest, similar to 5-FU. No differences were observed in cyclin B1+ or cyclin A2+ cell populations (Figure S2). A small elevation in the number of phospho-histone H3+ cells was detected in PALA treated samples as compared to vehicle controls (4.9% vs. 3.1%, p = 0.0067), but as the total number of positive cells were a very small proportion of the tissue (<5%) and located at the base of tumours, it is unclear whether these cells are an integral component of the tumour and/or exposed to significant amounts of the drug. However, PALA-treated tumours contained a higher average number of Ki67+ cells per tumour than vehicle-treated controls (24.6% vs. 10.4%; p = 0.005) and a lower percentage of cyclin D1+ cells per tumour (39.4% vs. 48.9%, p = 0.0329; Figure S2), suggesting that these tumour cells may be undergoing cell cycle arrest in response to PALA treatment.25

3.4 Innate immune activation and enhanced recruitment of cytotoxic T cells are stimulated by topical PALA treatment

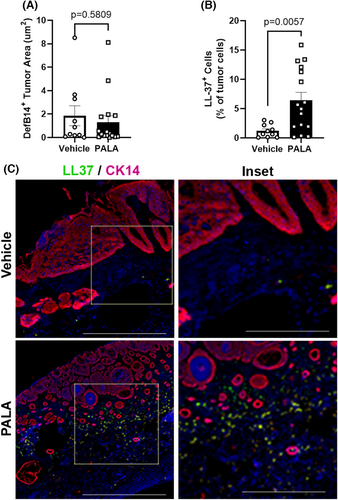

Prior work demonstrated that topical PALA treatment of bacterially infected human skin explants stimulated the expression of antimicrobial peptides, such as human β-defensin 2 (HBD2) and cathelicidin (LL-37), in a NOD2-dependent manner.21 Therefore, the levels of the mouse homologues of these AMPs (DefB14 and LL-37) were assessed in the tumour tissues of topically treated mice by multiplex immunofluorescent microscopy. DefB14 staining within tumours was diffuse, indicating AMP secretion from the cells, and the total area of DefB14 staining was not different among treatment groups (Figure 4A). In contrast, LL-37 staining was discrete and co-localised with nuclear DAPI staining, indicating that the numbers of cells expressing LL-37 should be quantified in the tumour tissues. The results demonstrate that LL-37+ cells were significantly increased in the PALA-treated tumour samples (Figure 4B).

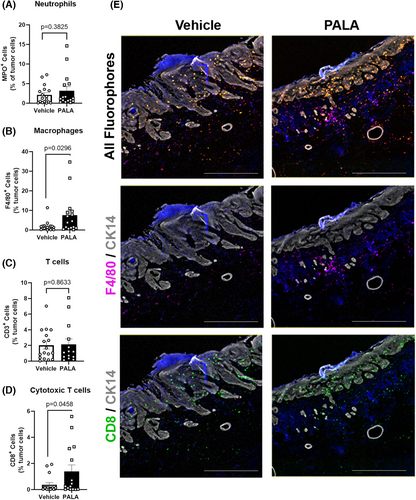

Neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages are major innate immune cell types that express both NOD2 and LL-37.19, 26 Therefore, tumour sections were analysed by multiplex immunofluorescent microscopy for markers of neutrophils (myeloperoxidase; MPO) and macrophages (F4/80) to determine whether either of these immune cell populations were recruited to tumour tissues in response to topical PALA treatment. The numbers of MPO+ cells were the same between treatment groups, indicating that neutrophils are not differentially recruited to tumour tissue (Figure 5A). Instead, PALA-treated tumours had increased numbers of F4/80+ macrophages relative to vehicle-treated controls (Figure 5B,E).

LL-37 has a controversial role in carcinogenesis. In some cancers it is upregulated and stimulates the generation of anti-inflammatory tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) that promote tumorigenesis, while in other cancer types LL-37 promotes the activation and expansion of anti-tumoral CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.26 To better understand the role of the LL-37+ cells and F4/80+ macrophages in PALA-treated tumours, the prevalence of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells was assessed by multiplex immunofluorescent microscopy. The overall number of CD3+ T cells within tumour tissue was the same between vehicle- and PALA-treated samples (Figure 5C). However, PALA-treated tumours had elevated numbers of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, compared to vehicle-treated controls (Figure 5D,E). Taken together, the results suggest that topical PALA treatment not only inhibits tumour proliferation, but also activates an innate immune response that results in an anti-tumoral cytotoxic T cell response.

4 DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that topically applied PALA is a potential new treatment for actinic keratosis and SCC of the skin. PALA is a simple molecule that can treat cancer through two distinct mechanisms.11, 13, 21 We have successfully shown that daily topical treatment with 2% PALA not only decreases tumour growth but also hinders progression of the tumour to more metastatic cell types. Multiplex immunofluorescent microscopy and immunohistochemical staining of the treated tumours showed changes in markers of cell cycle progression and increases in immune regulation corresponding to what is known about the mechanisms of action of this drug.13

PALA has been extensively tested as a systemic treatment for cancers previously.27, 28 Although treatments were quite effective in two murine models of cancer, the drug could not be used to treat human malignancies due to dose limiting toxicity.28 The topical application of PALA for skin cancer is a novel idea and, at low concentrations, we have seen no evidence that the drug causes any toxicity. We propose that topical treatment with PALA will have advantages over IMQ, 5-FU and tirbanibulin; current standards of care for NMSC that all cause severe skin irritation and inflammation.29 PALA did not induce an inflammatory response or skin irritation when applied to mice topically for up to 10 weeks. PALA is also not chemically reactive and can be stored at ambient temperature, and is therefore a viable option for use in areas with few economic resources.11 Although the efficacy of topical PALA will need to be compared to other existing therapeutic approaches to determine its overall clinical utility, topical PALA treatment represents a new candidate for an effective and broadly accessible treatment for NMSC.

Our results with topical PALA suggest that it may induce an immunotherapeutic effect without the need for an additional component for therapeutic action. Other studies investigated the potential of NOD2 activating agents as cancer immunotherapies and found they primarily act as immune adjuvants. Derivatives of the NOD2 bacterial ligand muramyl dipeptide (MDP) conjugated to lipid moieties have demonstrated promising anti-tumorigenic effects in animal models, as well as in human clinical trials.30 Direct injection of lipid conjugates of MDP into fibrosarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, B16-F10 melanoma or intravenous administration in a UV-induced skin cancer model or multiple metastatic liver cancer models prevented tumour growth, metastasis and/or improved survival of the cancer-bearing animals.30, 31 Although promising results were observed in early phase clinical trials, only two MDP derivatives (Mifamurtide/Mepact® and ImmTher®) have successfully completed phase III trials and gained approval for use in the European Union (Mifamurtide/Mepact®) or were granted FDA approval as an orphan drug (ImmTher®) for non-metastatic osteosarcoma after resection in combination with multidrug chemotherapy.32 It is thought that the therapeutic effects are primarily mediated through an adjuvant effect of these MDP/lipid immunotherapies that results in the enhancement of tumoricidal activity of macrophages,30, 33 a mechanism that is potentially similar to our topical PALA formulation. Recently, a muropeptide produced from Enterococcus faecium was described to augment checkpoint inhibitor cancer therapies in a NOD2-dependent manner.34 Similar to our findings with topical PALA, this muropeptide increased anti-tumoral cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, as well as impacted the macrophage population.

Both IMQ and PALA are immunomodulators that induce anti-tumoral immune responses. IMQ is a nucleoside in the imidazoquinoline family and is often used to treat NMSCs.29, 35 It activates anti-tumour immunity through stimulation of TLR7 in macrophages and other immune cells.29, 35 IMQ is known to upregulate the expression of interferon-α and interleukins 1, 6 and 8, as well as trigger autophagic cell death in macrophages.29, 35, 36 We have shown that PALA treatment does not increase these cytokines, and that macrophages are more abundant in the treated areas, showing that PALA works through an immune mechanism different from that activated by IMQ. Although the PALA-induced immune response is still under investigation, we postulate that it may be inducing anti-tumoral responses through enhanced cross-presentation of tumoral antigens to result in increased tumour-specific, cytolytic activity of CD8+ T cells. This hypothesis is supported by studies describing enhanced NOD2-dependent MHC class I and MHC class II antigen cross-presentation in cells stimulated with MDP,37-39 but remains to be formally tested.

Immune cell infiltration is seen in most malignancies.40 Macrophages are a major component of solid cancers and can promote tumorigenesis by stimulating angiogenesis, immunosuppression, invasion, and metastasis.41, 42 TAMs are key regulators of the connection between the immune system and cancer.43 TAMs can fuel, rather than limit, tumour progression, and can negatively impact responses to therapy and suppress T cell recruitment.43 However, activated macrophages are effective as a cancer immunotherapy, as they can kill cancer cells directly or indirectly through recruitment of other immune cells, such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes.44 Within tumours, T cells often become dysfunctional,45 and activated macrophages may be able to revive their cytolytic activity.44 Recent research highlights how the relationship between TAMs and the tumour microenvironment may lead to improved cancer therapies.46, 47 Our findings suggest that PALA may recruit and locally activate macrophages to enhance a cytotoxic T cell response.

PALA inhibits pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis and inhibits cellular proliferation through depletion of dCTP and dTTP, leaving treated cells unable to complete DNA synthesis.11 Although the expression of Ki-67 is often used as a marker of actively cycling cells, it is only absent from quiescent cells in G0 and may be highly expressed in cells arrested in other phases of the cell cycle.13 Cyclin D1 expression peaks at the end of G1 and is required to transition cells into S phase. Given the known impact of PALA on cellular pyrimidine pools,11 the increased number of Ki-67+ cells and decreased percentage of cyclin D1+ cells in PALA-treated tumours supports the conclusion that the cells may be undergoing arrest. These findings highlight the dual function of this drug as a cytostatic and immunomodulatory agent.

Topical treatment with PALA is not only a viable new candidate for skin cancer, but also potentially for any tumour accessible by non-invasive means, including oral cancers, vaginal cancers, cervical cancers and others. PALA may also improve the activity of other cancer therapies, such as checkpoint inhibitors or the topicals IMQ and 5-FU, through adjuvant or complementary mechanisms of action. We suggest that topical application of PALA should be pursued as a candidate for an alternative non-invasive and affordable treatment for various cancers in the future.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualisation, formal analysis, Investigation, Writing–Original Draft, Visualisation: Kala K. Mahen. Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–Review & Editing, Visualisation: Lilian Markley. Investigation, Writing–Review & Editing: Hope Klatka. Investigation, Writing–Review & Editing: Jolie Bogart. Methodology, Resources, Writing–Review & Editing: Vijay Krishna. Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing–Review & Editing: Edward V. Maytin. Conceptualisation, Resources, Writing–Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition: George R. Stark. Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing–Review & Editing, Visualisation, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition: Christine McDonald.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Andrelie Branicki, BS, HTL, and Ajay Zalavadia, PhD in the Cleveland Clinic Imaging Core for their expert assistance with multiplex immunohistochemistry and image analysis, the animal husbandry staff of the Cleveland Clinic Biological Resources Unit, John Petrich, MS, RPh in the Cleveland Clinic Investigational Drug Service for assistance with topical formulation, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI)/ Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD)/ Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) Open Chemical Repository (http://dtp.cancer.org) for providing PALA. This work was supported by a Cleveland Clinic Caregiver Catalyst Grant (to C.M. & G.R.S.), and philanthropic support from the McDonald Family Trust. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the funders.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data generated in this study are available within the article and Supplementary Data files.