Generalized pustular psoriasis – a model disease for specific targeted immunotherapy, systematic review

Abstract

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare, multisystemic skin disease characterized by recurrent episodes of pustulation. GPP can be life-threatening and is often difficult to treat. In the era of precision medicine in dermatology, GPP stands exemplary for both challenges and chances—while new treatments offer great hope, there is urgent need for better definition and stratification of this severe and heterogeneous disease. Our objective was to systematically review the literature for evidence of efficacy of targeted immunotherapy and their mode of action in the context of clinical phenotype, classification and pathogenesis of adult GPP. Classifying GPP is challenging since clinical criteria for description and diagnosis are not consistent between expert centres. We therefore defined diagnostic feasibility of the reviewed cases by assessing four criteria: compatible clinical history, typical dermatological features and/or diagnostic histopathology, consistent clinical pictures and the DITRA status. Pathogenesis of GPP is mediated by pathways that partly overlap plaque type psoriasis, with a more pronounced activity of the innate immune system. Both IL-1 and IL-36 but also IL-17 play a major role in disease formation. We ascertained a total of 101 published cases according to our predefined criteria and identified TNF-α, IL-12/23, IL-17 and IL-1β as targets for immunotherapy for the treatment of GPP. Of those cases, 61% showed complete response and 27% partial response to targeted immunotherapy. Only 12% experienced weak or no response. These data indicate that specific immunotherapy can be used to effectively treat GPP, with most evidence existing for anti-IL-17 agents.

1 INTRODUCTION

Generalized pustular skin eruptions are defined as the occurrence of a rash composed of sterile or non-sterile pustular lesions varying in size and localized either subcorneal, intraepidermal or at the basement zones of the epidermis. A wide spectrum of cutaneous diseases or reactions are associated with pustular eruptions. Form these, infectious pustular dermatoses like impetigo, tinea or whirlpool-dermatitis are distinguished from non-infectious pustular skin diseases. Those sterile pustular rashes include drug eruptions like acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), or chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin diseases like subcorneal pustular dermatosis and generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP). While GPP is often classified a variant of psoriasis, clinical, histological and recent genetic evidence suggests that the GPP can be regarded as a distinct clinical entity.1, 2 GPP is a rare, multisystemic inflammatory, potentially life-threatening variant of psoriasis. It produces recurrent flare-ups of sudden onset, which are characterized by widespread sterile pustulosis and systemic inflammation including fever, leucocytosis, general malaise and extracutaneous organ involvement which can result in significant morbidity and even mortality.3-6 Early treatment is essential to prevent complications such as congestive heart failure, bacterial superinfection and death, though finding a successful therapy can be challenging.7-9 Treatment options range from topical steroids to a combination of systemic potent immunosuppressive agents.

GPP has first been described by von Zumbusch in 191010 on a man with chronic plaque psoriasis developing nine recurrentepisodes of erythema and oedema with multiple pustules accompanied by fever and general malaise which covered at time almost the whole body.

More than a century after von Zumbusch's first description, definition and diagnosis of GPP are still not consistent between expert centres. The current literature provides numerous case reports and case series but only few studies on larger patient cohorts investigating the clinical presentation, the pathogenesis and the treatment of GPP. Recently, Navarini et al11 published the first European consensus statement concerning the definition of GPP.

The main objective of our report is to systematically review the published literature for new biological agents for targeted immunotherapy regarding efficacy and mode of action in the context of the pathophysiology of adult GPP. Therefore, we also review clinical presentation of GPP. We identified a total of 32 publications, reporting on 101 patients where targeted immunotherapy has been used to treat adult GPP. Since the majority of evidence in the literature refers to the von Zumbusch type GPP we primarily focused on this type.

A systematic electronic literature search of the PUBMED database was performed. We used the search term “generalized pustular psoriasis” to identify all relevant articles from its inception to December 2017. The article language was limited to English and German. Certainty of correct diagnosis of the screened GPP cases was classified as “definite”, “likely” and “suspected” based on four criteria:

- Compatible clinical history (recurrent episodes, sudden onset, systemic symptoms including fever, leucocytosis or CRP elevation, history of psoriasis etc.)

- Typical clinical dermatological features and/ or diagnostic histopathology

- Consistent clinical pictures

- Deficiency of the IL-36 receptor [IL-36R] antagonist (DITRA)

For a “definite diagnosis of GPP”, we set a limit of three, for “likely” diagnosis two and for “suspected GPP” one criterion that the respective case hat to meet. If less than one criterion was evident in the report, the case was dismissed due to lack of evidence.

For evaluating the efficacy of targeted immunotherapy in treatment of GPP in absence of objective disease severity tools in most of the reported cases, we defined clinical response as follows:

- Complete response (CR) was defined by the use of the following terms: “almost total resolution”, “cleared”, “resolved”, “largely resolved”, “complete control”, “clinical remission”, “almost complete remission”, “substantial efficacy”, “very much improved”.

- Partial response (PR) was defined by the use of the following terms: “favourable response”; “controlled”, “improved”, “much improved”.

- No or weak response (NR) was defined by the use of those terms and “no response”, “poor”, “weak, “worsened” and “no change”.

Photographic evidence was also used to support evaluation of efficacy if adequate body surface area (BSA) was displayed (improvement of >50% for PR; >90% for CR). For reports presenting the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) as an objective outcome criterion, reaching a PASI50 was considered as PR and PASI90 as CR. Articles lacking any information about clinical outcome were deemed unassessable.

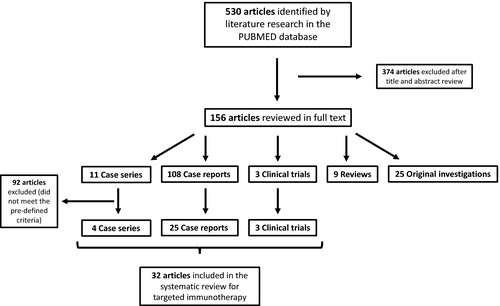

We reviewed the abstracts of all 530 publications yielded by the electronic search, excluded 374 articles after title and abstract review and classified the remaining into five categories: case series (CaS, 16), case reports (CaR, 108), clinical trials (CT, 4), reviews (4) and original investigations (25) (original investigations are defined as basic science articles). Regarding the evaluation of treatment of adult GPP we only included cases, case series and clinical trials applying targeted immunotherapy (biologicals) to treat GPP. From those 128 articles retrieved for full text review, 32 publications (CaS, 4; CaR, 25; CT, 3) met the predefined criteria and were included for the treatment section of this systemic review (Figure 1).

2 RESULTS

2.1 Epidemiology

GPP is an inflammatory skin disease that affects men and women of all ages and can also occur in children. The prevalence of GPP varies depending on ethnicity with highest numbers occurring in Asia (7.46 per million12) and is less often present in the Caucasian population (1.76 per million4). Thus, compared to psoriasis with an estimated prevalence varying between 0.9% and 8.5%,13 GPP is a rather rare disease and some experts regard it as an infrequent variant of psoriasis. It is discussed controversially whether GPP should be considered a distinct clinical entity rather than a variant of psoriasis.11, 14 In a Japanese epidemiological analysis of 9339 psoriatic patients, GPP was found to represent 1.3% of all clinical types of psoriasis.15 Furthermore, a history of plaque psoriasis is frequently observed in GPP varying from 31% to 77.4%.3, 5, 6, 12, 16, 17 The time between onset of ordinary psoriasis and first flare of GPP, also called prepustular duration, can take up to 6-20 years.5, 12

According to the first case series of GPP by Baker and Ryan published in 1968 and 1971, presenting a detailed clinical review of 104 and 154, respectively, GPP patients in Britain, adult GPP is mainly seen in middle and old aged with most of the patients being between 40 and 60 years of age.16, 18 Two other large case series investigating 102 GPP patients in a Malaysian cohort5 and 63 GPP patients from a single institution in North America (Mayo Clinic)3 showed similar data with a medium age at onset of adult GPP of 40.9 and 50 years, respectively. Considering gender distribution women seemed to be affected more often with a reported female to male ratio ranging from 1.2:1 to 2:1.5, 16, 19

2.2 Clinical presentation

2.2.1 Classification and definition

Clinical criteria for description and diagnosis of GPP are not consistently defined and vary internationally. Therefore, classifying GPP is challenging.

Since the appearance of GPP has a variety of clinical features, multiple attempts have been made in the past to stratify GPP into different subtypes. In one of the first approaches Baker and Rayen divided GPP into four different clinical patterns16: (i) acute GPP of von Zumbusch with widespread fiery erythema, sheeted pustulation and scarlatiniform peeling accompanied by systemic symptoms including fever, leucocytosis and general malaise; (ii) subacute annular GPP presenting more low-grade and being characterized by gyrate and annular pustular lesions and only minor systemic affection, (iii) exanthematic GPP emerging de novo, generally as a single short episode triggered by infections of drugs; and (iv) localized GPP where pustular lesions develop in and around ordinary psoriatic plaques. As the localized GPP described by Baker is not considered a variant of GPP by the recently published European Consensus Statement on Phenotypes of Pustular Psoriasis,11 but rather classified as a distinct variant of psoriasis vulgaris called “psoriasis cum pustulatione” (psoriasis with pustules), we prefer a different subclassification of GPP (Table 1) into (i) acute GPP, von Zumbusch (consistent with Baker type 1 and 3); (ii) annular GPP, also occasionally referred to as erythema annulare centrifugum-like psoriasis cum pustulatione (consistent with Baker type 2); (iii) GPP of pregnancy, also called impetigo herpetiformis; and (iv) juvenile and infantile GPP.6, 19-21 Yet, annular GPP is not considered a type of GPP by some authors since it is generally associated with minimal systemic symptoms.22

| Type | Name | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acute GPP, von Zumbusch | Commonest type in adults (2/3 of cases); sudden onset of widespread, erythematous patches or plaques studded with multiple pinhead-sized sterile pustules, which can cover the whole body leading to erythroderma, accompanied by systemic symptoms including fever, leucocytosis and general malaise |

| 2 | Annular GPP (erythema annulare centrifugum-like psoriasis cum pustulatione) | Subacute, more low-grade, characterized by gyrate and annular pustular lesions and usually only minor systemic affection |

| 3 | GPP of pregnancy (Impetigo herpetiformis) | Rare gestational dermatosis with typical onset in the last trimester of pregnancy with rapid resolution in the postpartum period |

| 4 | Juvenile and infantile GPP | Clinical phenotype mostly similar to annular GPP, more benign with higher rates of spontaneous resolution and long-term remission |

A first attempt to find a European consensus for the clinical criteria of GPP was conducted by the European Consensus Statement on Phenotypes of Pustular Psoriasis11 in 2017. Hence, GPP is defined as sterile pustulosis on non-acral skin occurring with or without PV, with or without systemic inflammation and can be either persistent (>3 months) or relapsing (>1 episode).

Since GPP is considerably more frequent in Japan than Europe, explicit guidelines for GPP, regarding treatment and diagnosis, have been developed in the past. According to the diagnostic criteria provided in the therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of GPP by the Japanese Association for Dermatology, GPP can be absolutely diagnosed if the following four criteria are met22: (i) systemic symptoms; (ii) multiple, widespread pustules on erythematous skin over the whole body; (iii) histopathologically confirmed; (iv) recurrence of criteria 1-3. If only criteria 2 and 3 are met the diagnoses can be suspected.

2.2.2 Clinical symptoms

During this review, we primarily focus on the major subtype, the adult GPP von Zumbusch, representing more than two-thirds of GPP cases.5, 6

Regarding clinical symptoms, the acute stage of GPP needs to be distinguished from the chronic stage. A GPP flare usually begins with a sudden onset of widespread, erythematous patches or plaques accompanied with burning sensation. During disease progression, those lesions become studded with multiple pinhead-sized sterile pustules, which can cover the whole body leading to erythroderma. During acute exacerbation, pustules often merge to big lakes of painful pustules. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including abrupt fever, chills, general malaise and laboratory abnormalities compatible with systemic inflammation, such as leucocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hepatic enzyme elevation and hypoalbuminaemia. Usually, pustules resolve within several days, leaving erythema, extensive desquamation and at times erosions resembling severe skin burns or even toxic epidermal necrolysis. Nails can be affected, showing hyperonychia and subonychial pustules. In one-third of GPP patients, arthralgia is present. Mucosal manifestations may include geographic tongue, fissured tongue and ocular symptoms such as conjunctivitis. Patients may also exhibit cheilitis as the lips may become red, scaly and superficially ulcerated. Recurrent episodes of these flares during which new pustulation emerges is a classic feature of acute GPP.

During the chronic stage, the clinical appearance of GPP is highly variable, sometimes presenting with plaque type psoriasis lesions, recurrent localized pustules and/or non-specific erythematous plaques.5, 6, 12, 16, 18, 23-25

2.2.3 Trigger factors

Flares may occur upon exposure to a precipitating factor or for unknown reasons. Multiple trigger factors have been described in case reports and case series. Four major categories including pregnancy, infections, drugs and electrolyte imbalances can be identified.

GPP in pregnancy, also referred to as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare gestational dermatosis with typical onset in the last trimester of pregnancy with rapid resolution in the postpartum period. The exact etiology is still unknown, but hormonal changes related to pregnancy have been proposed as potential contributing factors.26, 27

Regarding infections, upper respiratory infections, varicella zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus and skin mycosis have been identified to stimulate the development of GPP.5, 16, 23, 28-30 Furthermore, flares of GPP have been reported after vaccination with monovalent H1N1 in a GPP patient.31

As for drugs, literature suggests that both withdrawal and administration of certain pharmaceutics can trigger the development of GPP. Most evidence for a drug precipitating a GPP flare exists for tapering of systemic glucocorticosteroids in psoriasis patients.5, 16, 32, 33 Thus, systemic steroids should be used carefully in patients with common psoriasis and GPP. Furthermore, multiple reports suggest that even weaning of potent topical steroids can induce a GPP flare.34-36 Other reports associate the withdrawal of cyclosporine with a GPP flare.37, 38 Considering the administration of drugs, a variety of different medications have been associated with GPP, like treatment with antibiotics (amoxicillin, penicillin),39, 40 antihypertensives (propranolol, ramipril),41, 42 paradoxical reactions with biologics such as anti-TNF-α and ustekinumab,43-47 PEGylated interferon,48 bupropion49, 50 and terbinafin.51, 52 However, since distinguishing AGEP, a pustular-type drug eruption and a common differential diagnosis of GPP, from GPP can be extremely difficult, new administration of drugs associated with the onset of GPP should be regarded with caution.

Several case reports also mention electrolyte disorders, more specifically hypocalcaemia eg secondary to hypoparathyroidism as a trigger for GPP. In one case, treatment with intravenous calcium and cholecalciferol even lead to a complete remission of GPP.5, 17, 53, 54

2.2.4 Comorbidity and complications

Like in psoriasis the most common comorbidity in GPP patients include obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes.5 However, during an acute flare GPP can be potentially life-threatening and result in death due to its multiple complications. The literature lists cardiovascular failure, secondary infections including pneumonia and sepsis, aseptic acute respiratory distress syndrome and neutrophilic cholangitis as the most common complications of GPP.55-62

2.2.5 Clinical course

The clinical course of GPP is highly variable and in general without treatment unstable and prolonged. Although disease free periods over the course of years exist, those are often interrupted be recurrences of pustular flares. In his review “The Prognosis of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis”18 of 1971, Ryan reported a mortality rate of GPP of 25% attributable to disease and its treatment. Today, through a better understanding of pathomechanics and novel targeted immunotherapy, this high mortality rate is fortunately in the past with more recent reports estimating a rate of 4%-7%.5, 6 However, even these numbers might be overestimated, since the use of targeted immunotherapy was not equally distributed in these two studies eg due to prohibitive costs and novel drugs not being available at the time.

2.3 Pathogenesis

To date, the exact aetiology and pathogenesis of GPP are still unknown. Like PV and other inflammatory skin diseases evidence for GPP suggests that both genetic and environmental factors are involved in its pathogenesis. Furthermore, recent research suggests that because of their clinical, histological and genetic differences, GPP and PV are distinct clinical entities, rather than variants of the same disease.11, 14, 63

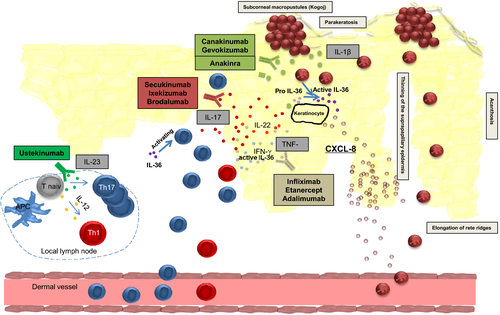

For a deeper understanding of GPP pathogenesis the morphological correlate, the histopathology, has to be taking into consideration. Biopsies of lesional skin in GPP show overall an psoriasisform like epidermal architecture, exhibiting parakeratosis, elongation of rete ridges, diminished stratum granulosum, elevated mitotic index and thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis. However, those changes seem to be more prominent in chronic GPP compared to acute GPP.64 The superficial dermis demonstrates numerous neutrophils migrating from the papillary capillaries to the epidermis to form subcorneal macropustules, termed spongiform pustules of Kogoj, a characteristic histological feature of GPP. Like in PV the upper dermis in GPP contains a perivascular lymphocyte-predominant infiltrate. In general, oedema and cell infiltration seem to be more marked in GPP compared to PV.23, 64, 65

These histomorphological similarities between GPP and PV are also seen on a gene expression level. Johnston et al63 demonstrated an overlap of the transcriptome between GPP and PV with a common upregulation of 184 genes. In particular, a significant overexpression of IL-17A, TNF, IL-1, IL-36 and interferons are detected both in PV and GPP.

Despite this overlap, the gene expression profile of GPP is rather skewed towards innate inflammation, while in PV the adaptive immune system seems to play the more crucial role. Consistently, IL-1 and IL-36, cytokines associated with the innate immune system, showed a more prominent upregulation in GPP compared to PV and gene expression analysis suggests that GPP primarily involves the activity of keratinocytes, neutrophils and monocytes. Johnston et al identified the IL-1/IL-36-chemokine-neutrophil axis to have a central role to the pathogenesis of GPP. Hence, IL-1 and IL-36 induce an inflammatory keratinocyte response, leading to recruitment of neutrophils in the epidermis and dermis via the expression of chemokines like IL-8. Furthermore, in vitro models demonstrated that both neutrophils and neutrophil proteases are able to regulate IL-36 activity, highlighting the role of the innate immune system in GPP.63

The influence of the cytokine IL-36 in pustular diseases was recently emphasized with the identification of the Interleukin-36-Receptor Antagonist (IL-36RA) deficiency, also referred to as DITRA (deficiency of the IL-36RA) in GPP patients.2 Marrakchi et al examined nine Tunisian multiplex families with autosomal recessive GPP and identified a homozygous missense mutation in IL36RN, the gene encoding for IL-36RA, which inhibits the activation of Interleukin-36α, β and γ, members of the Interleukin-1 family. DITRA leads to an unrestrained IL-36 activity, inducing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines like IL-8 from keratinocytes and consequently causing a neutrophilic infiltration.2 Since its first description, so far 16 different autosomal-recessive mutations of IL36RN defect, both in the European and the Asian population have been described, accounting for approximately 25% of GPP cases.11 Matching the clinical phenotype of GPP to DITRA shows a younger age of first onset, less frequent association with concomitant PV and higher risk of systemic inflammation in patients with the IL36RN defect compared to noncarriers.1, 66, 67 Thus GPP with PV is genetically different from GPP alone. However, pathogenic mutations of IL36RN have also been described in healthy populations, indicating that modifier genes and environmental triggers may contribute to the disease.14 Besides DITRA, mutations in CARD14 and AP1S3 have also been associated with GPP, with defects in CARD14 predisposing for GPP with concomitant PV.11, 68

As for the pathogenetic overlap to PV, evidence suggests that PV is the pathological consequence of a T-cell mediated immune response, in particular, a subset of T-helper (Th) cells, Th17 cells and their effector cytokine IL-17 have been described as a central mediator of the immune pathogenesis of psoriasis.69-71 IL-17A is highly expressed in PV and mediates the migration of neutrophils to psoriatic lesions by chemokines eg released from IL-17A-stimulated keratinocytes.72 Like in GPP, psoriasis histopathology also presents with neutrophilic infiltration which is both located around dermal vessels and accumulated forming epidermal micro abscesses. Therefore, IL-17A as a potent inducer of tissue inflammation and neutrophil recruitment has been suspected to play an important role in the pathogenesis of GPP with a great abundance of neutrophils. Besides the gene expression analysis by Johnston et al showing a significant upregulation of IL-17A both in PV and GPP, Kakeda et al73 supported this hypothesis by demonstrating that IL-17A expressing cells are significantly increased in epidermis, especially in subcorneal psutules, and the dermis of GPP patients compared to normal skin. Innate immune cells like neutrophils seemed to be an important cellular source of IL-17 in GPP, while in PV T cells are the predominant source of IL-17A.73 Furthermore, IL-23, the maintenance factor of IL-17 production which is highly expressed in psoriasis71 is also expressed in GPP.74 Moreover, serum cytokines of IL-17 and IL-22, two characteristic Th17 cytokines, are significantly increased in GPP and palmoplantar pustulosis, a localized form of pustular psoriasis.75, 76 Thus, the IL-23/Th17 axis also seems to play an important role in GPP.

More recently, Arakawa et al77 highlighted a link between the innate and adaptive immunesystem in the pathogenesis of GPP by demonstrating an enhanced proliferation of IL-17 producing CD4+ T-cells via signalling of IL-36.

In summary, evidence suggests that GPP uses immunologic pathways both overlapping and independent from PV, supporting the theory that GPP and PV are siblings, but not twins. Figure 2 displays the main mediators of GPP pathogenesis including targets for immunotherapy.78

2.4 Treatment

Most patients require continued therapy to avoid resurgence of flares. Conventional treatment options for GPP include retinoids, ciclosporin, methotrexate and UV phototherapy.8 While some patients may respond to these therapies, in many this type of treatment fails, or response is partial.

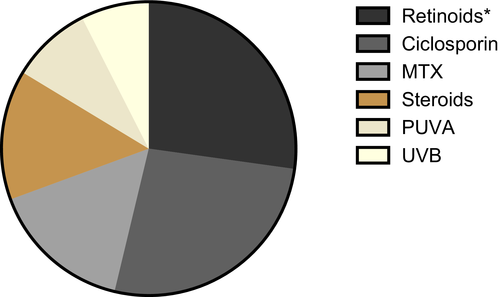

Since the disease course of GPP can vary from acute life threatening to self-limiting and benign, choice of treatment should be made according to disease severity and complications. Most of to date published recommendations regarding the therapy of GPP consider the use of retinoids as first-line therapy in adult GPP, although onset of action is relatively slow and the administration is limited by teratogenicity and organ-specific toxicity. For unresponsive, or patients who cannot tolerate retinoids, ciclosporin, methotrexate are recommended as first-line therapies.8, 23 Moreover, the combination of retinoids and psoralen plus UVA (Re-PUVA) is considered a standard therapy in some countries.79 In line with these recommendations, we identified within the 101 cases included in the detailed treatment review, that the two most common agents used in the treatment of GPP, are ciclosporin and retinoids followed by MTX (Figure 3). Although systemic steroids, for the risk of triggering a GPP flare, should only be used in severe and vitally threatening cases, they are used in more than 15% of the reviewed cases. UV light therapy including PUVA and UVB seem to play a minor role. As for the efficacy of conventional therapies in GPP there are no available randomized controlled trials. Moy et al80 report about 11 patients with GPP treated with retinoids, were control of pustulation and systemic symptoms was achieved in 10 cases, although additional therapy was necessary to achieve complete clearing.

While conventional agents might work in benign courses of GPP, in severe cases where early and high efficacy treatments are essential to prevent the potential for complications and mortality, response is often incomplete. Therefore, new and more effective treatment options are urgently needed.

Regarding the overlap in pathogenesis of PV and GPP, specific targeted immunotherapy used to treat moderate to severe plaque type psoriasis like anti-TNF-α, -IL12/IL23, -IL-17, showing an excellent short- and long-term efficacy and a favourable safety profile, are also applied in GPP. These biologic agents target highly specific, disease characteristic pathways of the adaptive and innate immune system and have fundamentally changed the therapy of chronic inflammatory diseases since their emersion in the late 1990's.81, 82

For the purpose of evaluating the efficacy of targeted immunotherapy in GPP, a total of 25 case reports, 4 case series and 3 clinical trials have been included for a detailed review. We identified a total of 101 cases treated with biologics targeting TNF-α, IL12/IL23, IL-17 and IL-1.

The patient characteristics including demographics, feasibility of diagnosis, duration of treatment and follow up (after treatment cessation) and the overview of clinical response according to the different targets are shown in Table 2. A more detailed overview listing each publication including its specific biologic with dose, efficacy parameters, number of patients, concomitant immunosuppressant medication and the DITRA status is shown in Table 3.

| Targets | n | Gender, % (n) | Mean age, y (SE) | Diagnosis, % (n) | Clinical response, % (n) | Mean disease duration prior, y (SE) | Mean treatment duration, m (SE) | Follow-up, m (SE) | History of Psoriasis, % (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Definite | Likley | Suspected | CR | PR | NR | |||||||

| TNF-α | 55 | 73 (38) | 27 (14) | 45.6 (3.8) | 30.9 (17) | 14.6 (8) | 54.5 (30) | 58.1 (25) | 27.9 (12) | 14.0 (6) | 12.5 (2.4) | 9.3 (1.9) | 2.6 (1.4) | 30.9 (17) |

| IL-12/IL-23 | 7 | 86 (6) | 14 (1) | 61.8 (9.9) | 42.9 (3) | 42.9 (3) | 14.2 (1) | 85.7 (6) | 0 (0) | 14.3 (1) | 11.7 (6.5) | 20.9 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 57.1 (4) |

| IL-1 | 7 | 40 (2) | 60 (3) | 51 (2) | 71.4 (5) | 0 (0) | 28.6 (2) | 20 (1) | 80 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.9 (1.2) | 9.5 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 28.6 (2) |

| IL-17 | 32 | 50 (16) | 50 (16) | 51.6 (3.2) | 100 (32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 66.7 (20) | 23.3 (7) | 10 (3) | 12.2 (5.1) | 12.7 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 28.1 (9) |

| Total | 101 | 65 (62) | 35 (34) | 49.2 (2.75) | 56.4 (57) | 10.9 (11) | 32.6 (33) | 61.2 (52) | 27.1 (23) | 11.0 (21.9) | 11.1 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.83) | 31.7 (32) | |

- CR, complete response; IL, interleukin; n numbers; NR, no or weak response; PR, partial response; SE, standrad error; y, years; follow-up is defined as duration after cessation of targeted immunotherapy.

| Target | Drug | Dose | Efficacy | Concomitant immunsup-pressant medication | DITRA | Type | Author | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pustule, cleareance, d | Clinical improvement | Type of clincial response | |||||||

| TNF-α (n = 55) | Infliximab (n = 29) | NA | 2 | 8/10 | CR (NA), PR (NA), NR (2) | 2/10 (2) | CaS | Viguier M. | |

| Like PV | NA | 3/3 | CR (2), PR (1) | NA | CaS | Poulalhon N. | |||

| Like PV | NA | 4/4 | PR (2), CR (2) | NA | CaS | Matsumoto, A | |||

| Like PV | NA | 3/3 | CR (3) | 2/3 (2) | CaS | Sugiura K. | |||

| Like PV | 2 | 1/1 | PR | NA | CaR | Chandran N. | |||

| Like PV | 1 | 1/1 | PR | NA | CaR | Smith N. | |||

| Like PV | 2 | 1/1 | PR | NA | CaR | Newland M. | |||

| Like PV | 2 | 1/1 | CR | NA | CaR | Schmick K. | |||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | CR | Acitretin 35 mg/d | NA | CaR | Tang M. | ||

| 4-5 mg /kg bw | 3 | 2/2 | CR (2) | Prednisolon 30 mg/d (1) | NA | CaR | Weishaupt C | ||

| 3 mg / kg bw | 2 | 2/2 | PR (1), CR (1) | Acitretin 20 mg/d (1) | NA | CaR | Kim H. | ||

| Adalimumab (n = 15) | NA | 17.5 | 2/3 | CR (NA), PR (NA), NR (1) | 1/3 (1) | CaS | Viguier M. | ||

| 80 mg eow | NA | 4/4 | PR (2), CR (2) | NA | CaS | Matsumoto A. | |||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | CR | CyA 400 mg/d and MTX 20 mg/w | NA | CaR | Callen J. | ||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | CR | Acitretin 50 mg/d | NA | CaR | Gallo E. | ||

| 80 mg eow | NA | 2/2 | PR (2) | MTX 5 mg/d | NA | CaR | Kawakami H. | ||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | PR | 1/1 (1) | CaR | Huffmeier U. | |||

| 80 mg eow | 5 | 1/1 | CR | NA | CaR | Kimura U. | |||

| 40 mg ew | NA | 1/1 | CR | NA | CaR | Zangrilli A. | |||

| Like PV | 5 | 1/1 | CR | MTX 10 mg/d | NA | CaR | Gkalpakiotis S. | ||

| Etanercept (n = 11) | NA | 18 | 2/4 | CR (NA), PR (NA), NR (2) | 2/4 (1) | CaS | Viguier M. | ||

| 25-50 mg BIW | NA | 6/6 | CR (6) | NA | CaS | Esposito M. | |||

| 50 mg BIW | NA | 0/1 | NR | 1/1 | CaR | Huffmeier U. | |||

| IL-12/IL-23 (p40) (n = 7) | Ustekinumab (n = 7) | Like PV | NA | 4/4 | CR (4) | Acitretin 10-20 mg/d (3) | 1/4 | CaS | Arakawa A. |

| Like PV | NA | 0/1 | NR | NA | CaR | Matsumoto A. | |||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | CR | CyA | NA | CaR | Storan E. | ||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | CR | NA | CaR | Dauden E. | |||

| IL-1 (n = 7) | Anakinra (n = 4) | 100 mg /d | NA | 1/1 | PR | Prednisolon | 1/1 (1) | CaR | Huffmeier U. |

| 100 mg /d | NA | 1/1 | PR | Prednisolon 10 mg/d | 0/1 | CaR | Skendros P. | ||

| NA | NA | 2/2 | CR (NA), PR (NA), | NA | 1/2 | CaR | Viguier M. | ||

| Canakinumab (n = 1) | 150 mg e4w | NA | 1/1 | CR | Hydroxyurea, Prednisolon | 0/1 | CaR | Skendros P. | |

| Gevokizumab (n = 2) | 60 mg e4w | NA | 2/2 | PR (2) | NA | CT (OL) | Mansouri B. | ||

| IL-17 (n = 32) | Brodalumab (n = 12) | 140-210 mg eow | NA | 9/12 | CR (6), PR (3), NR (2)a | Retinoid (1) | NA | CTP3 (OL) | Yamasaki K. |

| Ixekizumab (n = 5) | Like PV | NA | 5/5 | CR (2), PR (3) | Prednisolon <10 mg/d (NA) | NA | CTP3 (OL) | Saeki H. | |

| Sekukinumab (n = 15) | Like PA-PV | NA | 10/12 | CR (9), PR (1), NR (1)b | CyA (4), Etretinate (3), MTX (1), Prednisolon (1); | CTP3 (OL) | Imafuku S. | ||

| Like PV | 2 | 1/1 | CR | MTX | NA | CaR | Böhner A. | ||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | CR | NA | CaR | Mugheddu C. | |||

| Like PV | NA | 1/1 | CR | NA | CaR | Polesie S. | |||

- BIW, biweekly; bw, body weight; CaR, case report; CaS; case series; CR, complete response; CT, clinical trial; CTP3, clinical trial phase 3; CyA, cyclosporin A; d, day; DITRA, deficiency of the IL-36 receptor [IL-36R] antagonist; eow, every other week; e4w; every four weeks; IL, interleukin; MTX, methotrexat; NA, not available; NR, no or weak response; OL, open label; PA, psoriasis arthritis; PR, partial response; PV, psoriasis vulgaris; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

- a Analysis at week 16, one patient discontinued study due to AE.

- b Analysis at week 16, one patient discontinued the study.

2.4.1 Anti-TNF-α

TNF-α blocking agents, including infliximab, adalimumab and etanercept were early biologics approved for treatment of PV and also the first to be applied as off-label indication in GPP. The administration of those drugs lead to a rapid neutralization of TNF-α, a cytokine also found to be significantly upregulated in GPP inflamed skin lesions.63 Therefore, regarding the long history of anti-TNF drugs, most of the cases receiving targeted immunotherapy (n = 55) were identified in this group, with Infliximab (n = 29) being the most commonly used compound. Overall and even if a positive publication bias were taken into account, most of those patients responded to therapy with 58% showing a complete response and 28% a partial response. Only 6 patients showed a weak or no response. The onset of action seems to be particularly quick in patients receiving infliximab, exhibiting a pustule clearance of 1-3 days. Anti-TNF treatment seems also to be effective in patients having IL36RA deficiency, achieving a clinical response in 7 of 8 reported DITRA positive patients.7, 59, 83-98 Only three reports with a total of 5 cases provide significant follow-up data (>3 months) for the time after discontinuation of treatment with infliximab. Within those cases a relapse has been observed in two patients, while in three GPP remained stable, although two needed continuous treatment with acitretin.59, 83, 88

On the other hand, several reports suggest that TNF-a inhibitors can also trigger GPP flares as a paradoxical reaction.45, 99, 100

2.4.2 Anti-IL-12/IL-23(p40)

Ustekinumab neutralizes IL-12 and IL-23 through binding their common p40 chain and has been approved in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2009 showing greater efficacy compared to Anti-TNF-α agents.101 Since IL-23 also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of GPP, ustekinumab has been successfully used in treating GPP. Of a total of seven cases, complete remission has been achieved in 6 cases (1/6 DITRA positive) with only one GPP case with no or weak response, indicating that anti-IL-12/IL-23 therapy might be an effective option in GPP.84, 102-104

2.4.3 Anti-IL-1

Regarding the crucial role of the IL-1/IL-36-chemokine-neutrophil axis in the pathogenesis of GPP and the detection of the association of DITRA and GPP, targeted immunotherapies inhibiting the inflammasome have been applied in the treatment of GPP. Of those, anakinra, a recombinant interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1-RA) and the IL-1β targeting monoclonal antibodies canakinumab and gevokizumab have been identified by literature research.94, 105-107 In a total of 7 cases, complete response was observed in 2 cases and partial response in 5 cases. Interestingly, efficacy was also reported in cases with an absent DITRA status. Thus, targeting the IL-1 pathway in GPP patients might be effective independent from the IL-36RA mutation status.

2.4.4 Anti-IL-17

In 2015, secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody that selectively binds and neutralizes interleukin-17A, was approved as first-line therapy for plaque psoriasis after demonstrating remarkable results during phase III trials and subsequently showing superiority in efficacy compared to ustekinumab.108, 109 With ixekizumab and brodalumab, two other biologics targeting the IL-17 pathway have been approved as first-line therapy for plaque psoriasis in 2017, showing similar efficacy as secukinumab.110, 111 Considering the upregulation of IL-17 and the pronounced neutrophilic infiltration within the skin of GPP patients, targeting IL-17 in GPP, a cytokine mediating the migration of neutrophils, seemed most promising. We identified a total of 32 cases of GPP patients treated with the mentioned anti-IL-17 agents, including three open-label phase III trials with a total of 29 subjects. Overall, 66.7% demonstrated a complete response, 27.1% a partial response and 10% a weak or no response. There are no published data concerning the efficacy in DITRA positive patients.

3 CONCLUDING REMARKS

GPP is a heterogenous disease that lacks consistent classification and stratification. The challenge for the future is therefore to standardize diagnostic criteria, validate clinical endpoint parameters and subsequently further establish precision medicine in this field. At this juncture, literature indicates that specific immunotherapy targeting TNF-α, IL-12/23, IL-1 and IL-17 can indeed be used to effectively treat GPP, although biomarkers predicting therapy outcomes are unknown. Furthermore, due to the lack of follow up data after cessation of targeted immunotherapy, the duration of treatment to control this chronic relapsing disease remains to be determined.

Two limitation applies to this study. There is a potential source of a selection bias since due to the higher prevalence most of the published cases cited in this review are from Asia. The results might therefore not fully apply for all ethnicities having a different genetic background. Furthermore, a tendency to publish only positive therapeutic results and possible spontaneous remissions not related the therapy need to be taken into account.

As a result of the limited number of published reports with targeted immunotherapy in GPP, the lack of head-to-head studies and the publication bias mentioned above a direct comparison between the individual biologic groups is not possible. With our review, we wanted to give an overview about new treatment options that have been successfully used in the treatment of GPP and also provide some standardization regarding clinical response.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For their contribution to this review, the authors thank: Felix Lauffer, MD; of Department of Dermatology and Allergy Biederstein, Technical University Munich.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr(s) AB, AN and KE, had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: AB and KE Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: AB Drafting of the manuscript: AB Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AN and KE Obtained funding: none (list the last names of the authors). Administrative, technical, or material support: none (list the last names of the authors). Study supervision: KE (list the last names of the authors). All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.