Navigating the Epidemiology and Complexities of Dental Trauma in Southeast Asia: A Multi-Disciplinary Scoping Review

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Aim

To negotiate the available literature on ‘the epidemiology’ of dental trauma or DT in Southeast Asia, recognize key patterns, along highlight the gaps in the reporting of data and management.

Background

DT is an important public health problem in Southeast Asia. The differences in socioeconomic situation and healthcare protocol contribute to discrepancies in DT prevalence, along with management. Despite the impact, extensive data on DT remain limited in multiple countries within Southeast Asia.

Method

A scoping review was organized following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-ScR) instructions. Searches were conducted across databases (Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed) using applicable keywords. 18 studies were listed, with data extricated on study design, prevalence, population, as well as key findings.

Results

The pervasiveness of DT varied crucially, with the elevated rates reported in nations like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Important risk factors cover age (adolescents and children), motor vehicle accidents, and gender (males). A significant lack in the literature, especially from under-represented nations, as well as in rural areas was recognized.

Conclusion

The current scoping review reinforces the significant load of dental trauma in Southeast Asia, with differing prevalence across the area due to inconsistent reporting and socioeconomic disparities. Countries like Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia show higher DT rates, particularly among children, adolescents, and motor vehicle accident victims, while data gaps remain in other nations of Southeast Asia.

1 Introduction

Dental trauma (DT) refers to any injury to the teeth and their supporting tissues such as gums, alveolar bone, and periodontal ligaments [1]. Many factors, such as violent acts, accidents, and sports-related activities or falls, may play a significant role in the occurrence of these injuries [2]. DT has become an important global public health concern due to its high frequency and poor effects on the general health of individuals [3]. The acute effects of this condition manifest as bleeding, pain, and tooth loss, but the long-term continuation is functional compromise, poor appearance, and psychological stress [4]. Timely diagnosis and treatment of DT are essential to avoid such adverse consequences, but among the obstacles for this task is the need for dental care and health system limitations that differ considerably among regions [5].

In Southeast Asia, variations in healthcare systems and income disparities among countries are key contributors to the region's DT burden [6]. The 11 member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) collectively house over 650 million people, each with varying cultural, economic, and healthcare settings [7]. The area represents a mix of countries (with some close to rural areas and low-income level, along with others consisting mainly of urbanized cities and largely middle-income countries) [8]. Here, variations lead to a discrepancy in public health framework, professional accessibility, and care availability, which all control the incidence followed by reporting and managing dental trauma [3]. Furthermore, the occurrence of DT cases may jump with increasing industrialization, road traffic accidents in this area, and lifestyle factors like playing contact sports [9]. The trouble of DT in “Southeast Asia” is highly multifaceted and intricate, with cultural, socioeconomic, and environmental determinants affecting the epidemiological landscape of the region [10]. Previous studies have reported a high prevalence of dental trauma in children, with some zones showing high frequencies of 33% [3, 11]. The reasons for which these numbers are very high vary among the regions in the world but include more children participating in physical activities and outdoor sports now, less adult supervision, and low access to preventative measures or intervention as needed [12].

The DT is recognized to be common, but little is known about its prevalence in Southeast Asia [3]. Most of the countries in the region do not have organized DT surveillance systems, and data, if available, is distributed among academic research, hospital records, and school surveys at national or subnational levels [13]. Therefore, accurate and reliable data collection is essential to establish the true burden of DT in Southeast Asia, leading to the identification of ‘high risk’ populations, thus helping in planning preventive measures [14].

Pediatric dental trauma constitutes a significant public health issue in Southeast Asia, exacerbated by high traffic density, inadequate access to protective sports gear, and restricted availability of dental care, leading to a rise in trauma events among children [15]. In pediatric patients, trauma often results in the premature loss of primary teeth, potentially disrupting the natural progression of dental development. Premature tooth loss in children can influence jaw development, tooth alignment, and spacing, resulting in practical and esthetic consequences that may endure into adulthood. Traumatic loss of primary or permanent teeth in children can cause malocclusions. Premature loss of primary teeth disrupts the dental arch's natural spacing and alignment, causing crowding, midline shifts, and other misalignments that complicate orthodontic treatment. In addition to esthetic issues, malocclusions affect chewing efficiency and speech development, increasing the likelihood of adolescent orthodontic intervention [16].

The early identification and treatment of trauma-related dental injuries, especially in children, have been enhanced by developments in diagnostic technologies. More accurate evaluations of dental injuries are made possible by technologies like digital imaging, panoramic radiography, and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), which also lower the possibility of misdiagnosis and promote precise treatment planning [17]. In order to manage sequelae like malocclusions, early and correct diagnosis is essential since it enables prompt therapies that can avoid more serious crowding and misalignment problems. Disparities in care are caused by the fact that many rural and underprivileged parts of Southeast Asia still lack adequate access to these diagnostic instruments.

Surveillance systems are required not only to monitor incidence rates, but also to identify trends and direct public health policies and interventions. Governments can set up targeted preventative measures, deploy assets, and ensure that when a DT case is identified in response to effective surveillance, it is treated promptly [11]. Considering the complexity of healthcare systems and nonuniform resource allocation across Southeast Asia, its unified approach implies that much of DT could go underreported, especially in rural or underserved regions. The goal of this review is to navigate the available literature on the epidemiology of DT in Southeast Asia, identify key patterns, and highlight gaps in data reporting and management.

2 Methodology

2.1 Protocol

The present review was conducted following the design of the Preferred Reporting components for Systematic Reviews along with Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [18].

2.2 Research Questions

- What is the extent of the existing literature on the epidemiology of dental trauma in Southeast Asia?

- What are the key epidemiological patterns of dental trauma across Southeast Asia, including incidence, prevalence, and risk factors?

- What gaps exist in the literature regarding the reporting and management of dental trauma?

2.2.1 Search Processing

The search strategy employed a systematic and comprehensive approach to identify relevant literature on the epidemiology and surveillance of dental trauma in Southeast Asia. Searches were conducted across four major databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. To ensure the sensitivity and specificity of the search, both controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) and free-text keywords were used, particularly in PubMed.

For the PubMed search, relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) such as “Tooth Injuries”[MeSH], “Mouth Injuries”[MeSH], and “Epidemiology”[MeSH] were included to capture all indexed literature. These MeSH terms were combined with keywords such as “dental trauma,” “oral injury,” “traumatic dental injuries,” “prevalence,” “surveillance,” “Southeast Asia,” “ASEAN,” and individual country names (e.g., “Thailand,” “Malaysia,” “Vietnam,” “Indonesia,” etc.). Boolean operators were utilized to refine and expand the search: “AND” was used to combine relevant terms, “OR” to broaden the search, and “NOT” to exclude irrelevant studies (Table 1).

| Database | Search strategies | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((((Dental Trauma[Title/Abstract]) AND (Southeast Asia[Title/Abstract])) OR (Oral Injury[Title/Abstract])) AND (Epidemiology[Title/Abstract])) OR (Surveillance[Title/Abstract])) | 462 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS (“Dental Trauma”) AND TITLE-ABS (“Epidemiology” OR “Surveillance”) AND TITLE-ABS (“Southeast Asia” OR specific countries) | 48 |

| Web of Science | (((AB=(“Dental Trauma”)) AND AB=(“Southeast Asia”)) OR AB=(“Epidemiology”)) OR AB=(“Oral Injury”) AND AB=(“Surveillance”) | 244 |

| Google Scholar | (“Dental Trauma” OR “Oral Injury”) AND (“Epidemiology” OR “Surveillance”) AND (“Southeast Asia” OR country-specific searches) | 270 |

| Total | 1024 |

2.3 Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

This scoping review used well-defined exclusion and inclusion criteria, ensuring the quality and relevance of selected studies.

- Studies focused on the epidemiology of dental trauma in Southeast Asia.

- Studies provide data on the pervasiveness, incidence, risk factors, or results of DT.

- Peer-reviewed articles, governmental reports, or institutional publications, including cross-sectional, cohort, or observational studies.

- Only articles published in English were included to ensure consistency in analysis and to facilitate accurate interpretation of the findings.

- Studies focusing on non-Southeast Asian populations or irrelevant geographic regions.

- Articles not specifically addressing dental trauma or oral injuries.

- Publications in languages apart from English or studies without a full-text availability.

The titles along with abstracts recognized from the initial search were screened for relevance. Full-text articles were then retrieved for future evaluation. Two independent reviewers (MIK and AM) assessed the eligibility of studies based on the defined exclusion and inclusion criteria.

2.4 Data Processing and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (MIK and AM) conducted an independent search of databases and extracted relevant data from selected studies. The standard of the studies was evaluated based on the inclusion criteria, ensuring the reliability of the data presented in the review. The estimated Cohen's Kappa coefficient (K = 0.82) indicated a strong level of agreement between the two reviewers. In cases of disagreements during the study selection process, a senior reviewer (RB) was consulted for the final decision. Zotero version 7.0 was used to manage and organize the references and study data.

2.5 PCC Framework

- Population: Individuals of all age groups (children, adolescents, and adults) residing in Southeast Asian countries who have experienced dental trauma.

- Concept: The epidemiology, surveillance, prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and reporting mechanisms related to dental trauma.

- Context: Southeast Asia, including all 11 ASEAN member countries, considering diverse healthcare systems, socioeconomic conditions, and geographical settings (urban vs. rural).

3 Results

3.1 Selection of Study

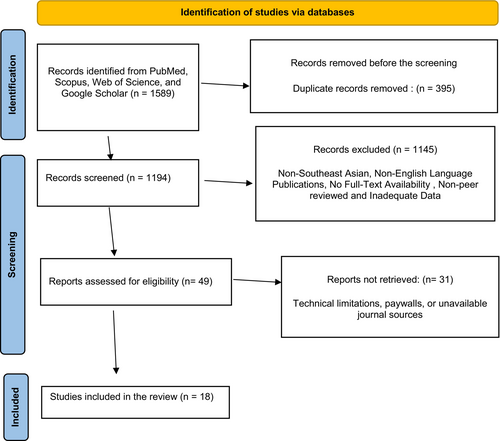

A total number of 1589 publications were listed from the online databases: PubMed (n = 589), Scopus (n = 65), Web of Science (n = 446), and Google Scholar (n = 489). No additional articles were found through manual search. After eliminating 395 duplicate studies, 1194 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Following the evaluation, 1145 studies were excluded as they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, resulting in 49 records for full-text review.

Out of the 49 records requested for retrieval, all were retrieved without any missing reports. However, 31 studies were excluded because the full reports were either inaccessible or did not align with the scope of the current review. Finally, a total of 18 articles were selected in the scoping review. The study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

3.2 Overview of Included Studies

The 18 selected studies varied in design (Table 2). The studies were conducted across various Southeast Asian countries, with most research focused on Thailand (n = 2), Vietnam (n = 1), Malaysia (n = 9), Indonesia (n = 4), Cambodia (n = 1), and Singapore (n = 1).

| Study | Country | Study design | Sample size | Population | Prevalence | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al., 2017 [10] | Malaysia | Retrospective | 630 | From 10 to 88 years age group |

Male- 85.4% Female- 14.6% |

Maxillofacial trauma represents a significant issue for the state of Sabah. Most affected males are in the age range of 21–30. Motor vehicle accidents (MVA) were the primary cause of trauma |

| Malikaew et al., 2006 [19] | Thailand | Cross-sectional | 2725 | Primary school children attending 53 of the 58 primary schools |

Males- 45.3% Females- 25.2% |

The pervasiveness of traumatic dental injuries (TDIs) between students is significant, indicating that key dental public health issues in countries like Thailand include not only dental caries, periodontal disorders, and dental fluorosis, but also TDIs |

| Hanh et al., 2018 [20] | Vietnam | Cross-sectional | 81 | From < 12 to > 18 years age group |

Males- 61.9% Females- 32.1% |

Despite the variety of clinical presentations of avulsed teeth and localized injuries, the most prevalent instances involve avulsed maxillary central incisors with an intact crown and an extra-alveolar duration exceeding 60 min without appropriate storage media |

| Sae-Lim and Yuen, 1997 [21] | Singapore | Retrospective | 129 | Participants with ages from 7 years to 48 years |

Males- 42.0% Females- 58.0% |

The majority dental injuries (periodontital tissue injuries without or with concurrent hard tissue injuries) and the count of traumatized tooth (more than 1) per individual typically suggest the more severe form of hospital-based dental trauma |

| Roehler et al., 2015 [22] | Cambodia | Retrospective | 5767 | All age group | — | Regional road safety advocates along stakeholders can create focused preventative actions and interventions to increase road safety among motorcycle riders by identifying the patterns of fatal motorcycle collisions in Cambodia |

| Hamzah et al., 2024 [23] | Malaysia | Retrospective record review | 295 | From 3 to 82 years age group | 37.7% | Early wound closure—within 6 h of the injury's onset—was linked to a decreased risk of wound complications in patients with RTA-caused face STIs |

| Loong, 2020 [24] | Malaysia | Retrospective | 153 | All age group | 6.5% | Motor vehicle accidents were the main cause of DT. The most prevalent type of soft tissue damage and the anatomical site where it occurs is the middle third of the face |

| Tumkosit, 2004 [25] | Thailand | Prospective study | 2934 | From 11 to 18 years age group | 9.3% | The study found that male students were more than female students to sustain a traumatic dental injury, and that public education about dental injury prevention is necessary |

| Gopinath et al., 2008 [26] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional study | 488 | School-going children aged from 12 to 16 years old |

12 years- 11.2% 16 years- 13.4% |

To maintain dental longevity and esthetics, it is important to draw attention to the potential causes and effects of these types of tooth fractures |

| Lee et al., 2017 [10] | Indonesia | Retrospective | 630 | All age group | 9.52% | The study found that males accounted for the majority of maxillofacial and dental trauma cases, the highest incidence occurred in the 21–30 age group, MVA was the primary cause, motorcyclists were the majority of MVA victims |

| Nik-Hussein, 2001 [27] | Malaysia | National oral health survey | 4085 | 16-year-old schoolchildren | 4.1% | There was a elevated prevalence of traumatic injuries between children in city areas compared to rural areas. The difference was not notable |

| Astari Miryasandra et al., 2013 [28] | Indonesia | Descriptive with survey method | 315 | Preschool children < 5 years of age | 5.1% | The incidence of crown fractures in primary anterior teeth among Early Childhood Education students in Cimahi is below 25% of the entire sample size |

| Abdullah et al., 2015 [29] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional study | 456 | The population of the study was consisted of Malaysian rugby players. | 27.0% | Understanding of teeth fracture management along with storage media varies between prior non-casualties and casualties |

| Ramli et al., 2011 [30] | Malaysia | Retrospective record review | 2986 | All patients diagnosed with dental injuries | 41.4% | The majority of dental and facial injuries at Seremban Hospital resulted from motor vehicle accidents and were primarily treated with conservative approaches |

| Esa and Razak, 1996 [31] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional study | 1519 | Aged between 12 and 13 years | 2.6% | Traumatic dental injuries should be treated effectively as soon as they occur or no later than 12 years after the injury |

| Luciana et al., 2019 [32] | Indonesia | A retrospective study | 35 | From 0 to 60 years old | 33.3% | Dentoalveolar trauma resulting from mandibular fractures includes trismus, floor of mouth hemorrhage, mastication pain, third trigeminal division paraesthesia and facial asymmetry |

| Wibowo, 2019 [33] | Indonesia | Observational descriptive study | 129 | All age group | 46.5% | The mechanism of significant facial trauma might result in maxillofacial fractures and brain damage. In 2016, motorbike riders accounted for 88.23% of maxillofacial fractures resulting from traffic incidents, indicating a significant risk of concurrent trauma |

| Royan et al., 2010 [34] | Malaysia | Retrospective record review | 268 | Below 7 years | 8.69% | The results of this study varied in certain aspects from those undertaken in other nations. The results are beneficial for resource allocation and preventive measures |

The studies spanned a publication period from 1990 to 2024, with populations studied including both children and adults. Several studies focused on specific groups, such as schoolchildren aged < 7 years, while others targeted adults or mixed-age populations, including both rural and urban communities. Sample sizes varied widely, with the smallest study having less than 100 participants and the largest including over 4000 individuals.

4 Discussion

The literature on the epidemiology of DT in Southeast Asia is relatively limited but diverse, with most studies focusing on specific populations or regions within individual countries. The included studies span multiple Southeast Asian countries, such as Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Singapore, and explore various age groups, with an emphasis on schoolchildren and adolescents.

This scoping review included a total of 18 studies, encompassing various study designs such as cross-sectional studies, retrospective record reviews, national oral health surveys, and prospective studies. The wide span of sample sizes, from large national surveys (e.g., 4085 participants in Nik-Hussein et al. [27]) to small cohorts (e.g., 35 participants in Luciana et al. [32]), highlights the diversity of the research area. The studies normally related to dental injuries occur from general trauma, motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), falls, and sports injuries, reflecting the wide spectrum of reasons related to dental trauma in Southeast Asia.

There is a perceptible geographic attentiveness to research, with Malaysia being the highest studied country, considered for 9 of the 18 included studies. Malaysian studies range from retrospective studies of hospital data [23, 30] to surveys of national oral health [27], indicating a huge focus on comprehension of the epidemiology of dental trauma. Other countries, such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam, have fewer studies, and Cambodia had only one study [22]. Notably, no studies were identified from Laos, Myanmar, or Brunei, which suggests significant gaps in the regional understanding of DT in these countries.

Most studies employed cross-sectional or retrospective record review designs, with only a few utilizing prospective study methods [25, 28]. Cross-sectional studies, such as those conducted by Malikaew et al. [19] in Thailand and Gopinath et al. [26] in Malaysia, provided a snapshot of DT prevalence in school-aged children, an age group at high risk for dental injuries. Retrospective studies often drew from hospital or clinic records to analyze the causes and demographics of dental injuries [10, 30], while national surveys offered insight into broader population-level trends [27].

The sample sizes of the studies varied significantly. For example, Lee et al. [10] studied 630 participants in Malaysia, while Nik-Hussein [27] examined a much larger sample of 4085 schoolchildren. These variations in sample size affect the generalizability of findings across the region. Furthermore, most studies examined specific subgroups within the population, primarily focusing on children and adolescents, particularly those aged 12–18 years [19, 26]. This focus on younger populations reflects the fact that dental trauma is most prevalent in this age group, as they are more likely to engage in physical activities that increase their risk of injury [35]. However, this emphasis may also leave gaps in understanding DT incidence in other high-risk populations, such as the elderly or individuals with specific occupations.

The epidemiological patterns of dental trauma in Southeast Asia exhibit significant variability across countries and populations. Several key findings can be drawn from the included studies regarding the incidence, prevalence, and risk factors associated with DT. The pervasiveness rates of DT in Southeast Asia differ widely and rest on the study design, country, and population. In Malaysia, pervasiveness rates start from 2.6% amidst 12–13-year-old school-going children [31] to 41.4% in a retrospective study of patients with dental injuries at Seremban Hospital [30]. Malikaew et al. in Thailand [19] reported a remarkable DT prevalence among primary school-going children (45.3% admits males and 25.2% admits females); on the other hand, Tumkosit [25] recorded a 9.3% prevalence among adolescents aged 11–18 years. Studies by Wibowo [33] in Indonesia, and Luciana et al. [32] saw even increased rates, mainly among individuals associated with motorbike accidents. A study by Wibowo [33] recorded that 46.5% of motorbike riders involved in traffic incidents sustained maxillofacial fractures, reinforcing the high risk of DT among this population. Hanh et al. in Vietnam [20] found a pervasiveness of 61.9% among males aged < 12 to > 18 years, depending on the avulsion of maxillary incisors, a usual form of DT.

The highest pervasiveness of dental trauma is detected in Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia, mainly in studies including motor vehicle accidents [30, 33]. The volatility in pervasiveness between rural and urban areas is another major pattern, as city areas report higher rates of DT, certainly due to higher participation in activities such as traffic-related incidents or sports. This finding was reinforced by Nik-Hussein [27], who reported a higher pervasiveness of traumatic injuries in urban areas compared to rural regions in Malaysia.

Studies recorded that dental trauma is more prevalent in the younger generation, mainly adolescents and children [19, 26]. This trend is ascribed to the reason that younger persons are more expected to engage in pursuits that higher their risk of injury, like participating in outdoor activities or playing sports. Additionally, studies reported that males are at increased risk of dental trauma compared to females [10, 25]. Such as Lee et al. [10] recorded that 85.4% of maxillofacial trauma cases in Sabah, Malaysia, took place among males, mainly those aged 21–30, escorted by motor vehicle accidents in the most common regions. MVAs are a crucial contributor to dental trauma in Southeast Asia. This is mainly obvious in countries like Indonesia, Cambodia, and Malaysia, where motorbike utilization is widespread. Multiple studies highlight the notable role of MVAs in donating to maxillofacial trauma, mainly amid young adult males [30, 33]. Roehler et al. in Cambodia, [22] related local road safety issues with the increased rate of DT, proposing that improving road safety could mainly lower DT incidence.

Another usual risk reason for dental trauma in Southeast Asia is involvement in sports, mainly contact sports like rugby. Abdullah et al. [29] reported a 27% prevalence of tooth fracture management along with storage media. These outcomes suggest the need for better preventive measures and awareness, like the use of mouthguards, mainly among athletes. The lack of standardization in dental trauma surveillance across Southeast Asia appears to be multifactorial. One major barrier is the absence of unified national policies or formal guidelines mandating routine data collection and reporting on DT. Without these frameworks, healthcare providers may not consistently document DT cases, resulting in fragmented or incomplete data. Additionally, resource limitations including inadequate funding for oral health programs, shortages of trained dental professionals, and a lack of digital health infrastructure further constrain the development of standardized reporting systems, especially in rural and underserved areas. Cultural and societal factors may also contribute; in many Southeast Asian countries, dental trauma is not widely recognized as a public health priority, and awareness of the importance of early intervention or preventive care remains low. These challenges collectively hinder the establishment of national DT registries and surveillance systems, emphasizing the need for targeted investment, policy development, and education to bridge existing gaps.

Multiple gaps in the literature along with the current practices of recording and managing dental trauma in Southeast Asia were recognized in this review. A significant gap in the existing literature is the absence of standardized dental trauma observation systems across Southeast Asia. A few countries, like Malaysia and Singapore, have somewhat organized systems in place to monitor as well as report dental trauma cases [21, 30]. Even in these countries, the recording mechanisms are initially hospital-based and fail to capture the full expanse of dental trauma in the general population, mainly in underserved or rural areas. The absence of a concentrated, standardized system for DT recording means that data on the occurrence and pervasiveness of DT are frequently fragmented, with few cases reported in hospital reports, others in school records, and still others in academic research studies. For example, in Vietnam, Hanh et al. [20] reported on a specific subset of dental trauma (avulsed teeth) among children, but there is no comprehensive national database to track other forms of dental trauma. The lack of a national or regional registry hinders efforts to accurately assess the burden of dental trauma and to implement effective public health interventions.

Another notable gap is the uneven distribution of research across Southeast Asia. As referred to earlier, the majority of studies involved in this review were supervised in Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia, and no studies were found in countries like Myanmar, Brunei, or Laos. This deficiency of research from a few Southeast Asian countries restricts the generalizability of records and advises that the true struggle of dental trauma in the area may not be reported accurately. The lack of research from some countries may be ascribed to various elements, including bounded resources for managing epidemiological studies, a dearth of trained individuals to manage trauma cases, along with a lower sort of oral health in the public health programs of these countries. Without more research from these underrepresented countries, it will be hard to develop an extensive grip on DT in Southeast Asia.

Specific studies illustrate these challenges. The Brunei Darussalam National Oral Health Survey (2014–2017) found a 9.1% overall DT prevalence among 5–15-year-olds, increasing with age and more common in boys. However, it lacked data on etiology and injury types [36]. A 2006 study (2006) in Vientiane, Laos, revealed similar age and gender trends (7% prevalence in 12-year-olds) and found that most injuries occurred during play or sports. Alarmingly, only 7% of Lao children with DT received treatment, highlighting unmet needs [37]. A 2009 study in Yangon, Myanmar, showed a 14.5% DT prevalence among 10–16-year-olds, with a staggering 99.5% of cases untreated [38, 39].

Several studies aimed to address gaps in the prevention and management of dental trauma. In 2015, Abdullah et al. [29] noted notable gaps in the understanding of tooth fracture management in rugby players. Sae-Lim and Yuen [21] reported that more acute forms of dental trauma, like injuries involving several teeth, were mostly inadequately treated or underreported. The lack of proper awareness and training in the management of DT is especially concerning in groups at high risk, such as individuals involved in motor vehicle accidents and athletes. Besides, the application of preventive actions, like mouthguards in sports, is not practiced widely across Southeast Asia. This gap in preventive care was focused on studies including schoolchildren and rugby players, where a large number of participants were ignorant of the outcomes of taking protective measures to prevent DT [26, 29].

Addressing pediatric dental trauma through protective strategies, including education on the importance of using mouthguards during sports and increasing parental awareness, is crucial to reducing the frequency and impact of early tooth loss in this population [40]. Furthermore, immediate post-trauma interventions, such as space maintenance, can help preserve the integrity of the developing dental arch and prevent complex orthodontic needs in later years. Early orthodontic evaluation is essential in children with a history of dental trauma to monitor any developmental deviations and address them proactively, thus reducing the complexity and cost of orthodontic treatment in adolescence. Providing accessible orthodontic assessments as part of routine trauma follow-up could be particularly beneficial in addressing alignment issues before they escalate [41]. By improving access to advanced diagnostic resources, countries in Southeast Asia can enhance early diagnosis, improve treatment outcomes, and prevent long-term complications associated with untreated pediatric dental trauma.

4.1 Implications for Public Health Policy

The outcome of this scoping review highlights the urgent requirement for Southeast Asian nations to improve dental trauma surveillance and integrate dental trauma prevention into national public health policies. Presently, many countries are in dearth of standardized surveillance systems, promoting fragmented data collection along with underreporting. Establishing national dental trauma registries and including dental trauma in broader oral health activity plans can increase resource allocation and data accuracy. Public awareness movements aiming at prevention, mainly in schools along with sports settings, are very crucial. Additionally, coaching healthcare providers, mainly in rural regions, in dental trauma handling can improve timely intervention followed by outcomes.

Targeted intermediation is also required for high-risk categories, such as athletes and motorbike riders, to prevent dental trauma. Measures like promoting mouthguard use in sports, expanding access to dental care in destitute areas, and enforcing helmet laws can remarkably reduce dental trauma incidence. Regional collaboration through ASEAN can help nations share data, best practices, and resources to address the load of DT more effectively throughout the region. Categorizing these strategies will assist in strengthening public health responses, along with reducing the long-term impacts of the health and economic situation of untreated DT in Southeast Asia.

4.2 Recommendations for Practice and Future Research

To improve dental trauma surveillance in Southeast Asia, nations should develop standardized recording protocols unsegregated into health databases, securing consistent data collection throughout rural and urban areas. Collaboration between government bodies and healthcare providers is important for streamlining recording processes and certifying accurate data. Guidelines and reporting essentials should be given to all healthcare amenities. Training healthcare providers, mainly in rural areas, is important for early identification and management of dental trauma cases. Empowering them with resources and skills will ensure better trauma reporting and timely management. Additionally, consolidating DT reporting into regular care practices will increase overall surveillance. However, future research should give priority to underrepresented nations and focus on long-term studies to assess the effectiveness of preventive strategies, like road safety interventions and mouthguards in sports. Comparative studies between rural and urban settings are also essential to identify disparities and guide targeted public health initiatives.

4.3 Limitations

The limitation of the current scoping review is the geographic imbalance, with data primarily from countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand, while other Southeast Asian nations are not presented, limiting region-wide conclusions. Additionally, the variation in study designs and inconsistent methodologies across studies makes it difficult to directly compare results, impacting the overall assessment of dental trauma in Southeast Asia.

5 Conclusion

This scoping review underscores the significant burden of DT in Southeast Asia, with varying prevalence across the region due to socioeconomic disparities and inconsistent reporting. Countries like Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia show higher DT rates, particularly among children, adolescents, and motor vehicle accident victims, while data gaps remain in other nations of Southeast Asia. To address DT effectively, Southeast Asian countries must implement public health strategies focused on prevention, awareness campaigns, and healthcare provider training, particularly for high-risk groups. Future research should target gaps in rural areas and underserved countries to guide comprehensive DT management across the region.

Author Contributions

Mohmed Isaqali Karobari: writing – original draft, visualization, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, data curation. Niher Tabassum Snigdha: writing – review and editing, visualization, investigation, data curation. Mohammad Fareed: writing – review and editing, validation, investigation. Viet Hoang: writing – original draft, visualization, supervision, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. Thantrira Porntaveetus: original draft, visualization, supervision, investigation, formal analysis, data curation. Gowri Sivaramakrishnan: original draft, visualization, supervision, investigation, formal analysis, data curation. Anand Marya: writing-original draft, visualization, supervision, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their thanks and gratitude to AlMaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for the support to publish this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.