Self-reported quality of life and hope in phase-I trial participants: An observational prospective cohort study

Abstract

For advanced cancer patients deliberating early clinical trial participation, adequate information about expected effect on quality of life (HRQoL) and hope, may support decision making. The aim was to assess the potential relation of HRQoL to eligibility for phase-I trial participation, and to observe the variations in patient-reported outcomes. Patients completed questionnaires at preconsent (n = 124), baseline (n = 96), and after first evaluation of a phase-I trial (n = 76). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to test differences between eligible and ineligible patients. Univariate logistic regression was performed for eligibility. Factorial repeated-measures ANOVA compared the outcomes of patients continuing vs. stopping participation after first evaluation over time. Eligibility is associated with significant better global health OR = 0.946, 95% CI [0.918, 0.975], p = 0.001, physical functioning OR = 0.959, 95% CI [0.933, 0.985], p = 0.002, role functioning OR = 0.974, 95% CI [0.957, 0.991] and better appetite OR = 1.114 95% CI [1.035, 1.192]. HRQoL outcomes like global health, social functioning and appetite decline in all patients and differ between patients continuing or having to end participation. Over time, hope and tenacity decline in all patients and coping strategies alter in patients stopping participation. Trial participation influences patient-reported outcomes. Global health may predict for eligibility and trial continuation. Informing patients could affect patients’ decision making.

1 INTRODUCTION

Patients with advanced cancer who have exhausted their regular treatment options may consider participation in early-phase clinical trials. Dose-finding is the primary goal of phase-I trials and efficacy is unknown. Therefore, it is important to inform patients about expected effects of trial participation (Godskesen & Kihlbom, 2017). This should not only be based on the biological background of the investigated compound, but also based on the general impact of trial participation affecting daily life.

Another issue in oncology phase-I clinical trial conduct is how to safeguard the palliative care for patients enrolled in such trials (Cassel et al., 2016; Van der Biessen et al., 2018). The systematic assessment of patient-related outcomes (PROs), such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and symptoms scores, could help to improve the delivery of adequate palliative care for patients with cancer on trial (Ferrell et al., 2017). Preliminary data of the randomised trial that integrated palliative care in phase-I trial participation showed that patients on trial score low on the ability to work, have a lack of energy, and are worried about losing condition, dying and losing hope (Ferrell et al., 2017). Furthermore, research towards hope at preconsent of phase-I trial participation showed that hope was the central motivator for participation and positively interacted with HRQoL. Hope formed a pact with coping strategies, such as tenacious and flexible coping, and the feeling of being in control (Van der Biessen et al., 2018).

Although most patients on trial are in a good condition, not all consenting patients are deemed to be fit to participate (Anwar et al., 2017; Ferrell et al., 2017; Olmos et al., 2012). The early implementation of HRQoL could be used to improve the selection of patients entering trials (Kluetz, Chingos, Basch, & Mitchell, 2016). In addition, HRQoL might complement clinical prognostics scores like the Royal Marsden Hospital prognostic score (RMS; Arkenau et al., 2009).

HRQoL is rarely investigated in potential phase-I candidates (Anwar et al., 2017; Atherton, Szydlo, Erlichman, & Sloan, 2015; Ferrell et al., 2017; Rouanne et al., 2013). Recent research in this field indicates that patients on trial who experience serious adverse events differ in baseline HRQoL from those who do not experience serious adverse events (Anwar et al., 2017). There is no association between baseline HRQoL and RMS (Anwar et al., 2017).

To be able to prepare and inform patients in an adequate way, we prospectively collected self-reported HRQoL, hope and coping strategies. The aim of this study was to assess the potential relation of HRQoL to eligibility for phase-I trial participation. Furthermore, the changes in HRQoL, hope and coping strategies were observed from preconsent to the first evaluation of a phase-I trial.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

This observational descriptive prospective cohort study was performed at the phase-I Unit of the Department of Medical Oncology, at a University Hospital in the Netherlands. The participating patients were referred to our phase-I unit for the first time. A total of 18 phase-I trials were recruiting patients. All patients had advanced or metastatic cancer and were potentially eligible for trial participation. The additional inclusion criteria for this cohort study were: older than 18 years and being able to speak and read Dutch.

The study was approved by the institutional review board and registered at the Dutch Trial Registry. From each patient, a written informed consent was obtained.

2.2 Procedures

During the informed consent procedure, patients were informed verbally about both phase-I trial participation and this study by their treating oncologist or the phase-I trial oncologist. They received written information about both studies, including the questionnaire form. The verbal and written information was given in accordance with approval from the Medical Ethical Commission, which included that participation was voluntary and the patient could withdraw at any time. The scientific nature of this study was explained both verbally and on paper, and stated it was not part of the proposed phase-I trial. In the following predecisional period, patients were asked to read the information and to complete the questionnaire at home. A telephone number of a nurse practitioner was included in case any questions would arise. At the informed consent visit, the patients discussed the phase-I trial option with the oncologist or nurse practitioner and were asked to return the questionnaire (T1). After given informed consent for the clinical trial, a screening period followed, which may take up to a maximum of 28 days. The next questionnaire was planned at baseline (i.e., start phase-I trial; T2). The last questionnaire followed after the first tumour evaluation visit, 6–8 weeks later (T3). Patients completed the questionnaire at T2 & T 3 at the outpatient clinic, during admission, or at home. They could return the questionnaire by mail.

2.3 Questionnaire and clinical information

Patients provided information about their gender, age, education and marital status. In addition, information was collected about cancer diagnosis, time since diagnosis, WHO performance status, consent to a novel oncology drug study, type of study, reasons for denying consent to a study, eligibility and subsequent start in the phase-I trial if applicable, and the outcome of the first evaluation of the experimental treatment.

- Physical functioning consisted of 5 items, for example “Do you have any trouble taking a long walk?” and “Do you need to stay in bed or a chair during the day?”

- Emotional functioning had 4 items, among which “Did you worry?” and “Did you feel depressed?”

- Role functioning had 2 items, “Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities?” and “Were you limited in pursuing your hobbies or other leisure time activities?”

- Cognitive functioning had 2 items, “Have you had difficulty in concentrating on things, like reading a newspaper or watching television?” and “Have you had difficulty remembering things?”

- Social functioning had 2 items, “Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your family life?” and “Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your social activities?”

It also includes three symptoms scales on fatigue, nausea and vomiting and pain. It contains six single items assessing dyspnoea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhoea and financial impact. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 1, “not at all” to 4, “very much.” The outcomes were added by scale and divided by the number of questions. The raw score was standardised by applying linear transformation. The global health scale is scored on a 7-point modified linear analogue scale ranging from 1, “very poor” to 7, “excellent.” A high score on the functional scales represents a high score of functioning, while a high score on the symptom scales represents a high level of symptom problems.

Hope was measured through the Dutch translated and validated version of the Herth Hope Index (HHI). The HHI measures a global, nontime oriented sense of hope (Van Gestel-Timmermans, Van Den Bogaard, Brouwers, Herth, & Van Nieuwenhuizen, 2010).

The translated assimilation and accommodation coping-scale (AACS) was used to measure coping. The AACS consists of two scales: one for Tenacious Goal Pursuit (tenacity) and one for Flexible Goal Adjustment (flexibility). Tenacity is connected to assimilation, where circumstances are transformed in accordance with personal preferences. Accommodative coping (flexibility), on the other hand, adjusts these preferences to the (new) situation (Taylor, 1999).

The Locus of Control (LoC) questionnaire measures generalised expectancies for internal vs. external control. People with an internal LoC believe that their own actions determine the goals that they obtain, while those with an external LoC believe that their goals in life are generally outside of their control (Rotter, 1966). Additional information of the components is described in an earlier paper.

The RMS was categorised according to 3 variables: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), normal (0) vs. LDH > ULN = 248 U/L (+1); albumin, ≥3.5 g/dL (0) vs. <3.5 g/dl (+1); and the number of metastatic sites of disease, ≤2 (0) vs. >2 (+1) (Arkenau et al., 2008). After summing the value for each variable, the patients were assigned to a good prognostic group (0–1) or a poor prognostic group (2–3). For general comparison of our data, we used the EORTC QLQ-C30 outcomes of 4,812 patients with recurrent/metastatic cancer, based on EORTC data of 2011, as reference group (Scott et al., 2008). The survival status of all patients was assessed on 31 May 2017, and the survival time was defined as the period between the consent visit and time of death or last follow-up.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Patients’ demographics, clinical characteristics and questionnaires were summarised, using descriptive statistics. The data were analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 for Windows. A linear transformation was performed to standardise the raw scores of EORTC QLQ-C30. The standardised scores range from 0 to 100 (Aaronson, 1992; Aaronson et al., 1992).

2.4.1 Eligible vs. ineligible patients

We compared the EORTC QLQ-30 of the eligible vs. ineligible patients at the start of screening using the preconsent data (T1). These comparisons were analysed using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to study the relation between eligibility for phase-I trial participation and the following variables at preconsent: age, sex, marital state, WHO performance status, RMS, and the items of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eligibility is defined as fulfilling the in- and exclusion criteria of a phase-I trial and the actual participation in this trial. Correction for multiple testing was deemed necessary for the EORTC QLQ-C30 scales and items (15 in total), where the Bonferroni correction was applied and hence a p-value of <0.0033 was considered significant for both the nonparametric and logistic regression analyses.

2.4.2 Continuing vs. stopping participation after first evaluation

Next, we compared the EORTC QLQ-30, hope and coping strategies of the patients who were able to finish the questionnaires at all 3 time points. A factorial repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare the data collected at T1, at baseline of the phase-I trial (T2), and first tumour evaluation (T3). In case the assumption of sphericity was violated (results not shown); the Huynh-Feldt correction was applied to the p-values. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant without correction for multiple testing.

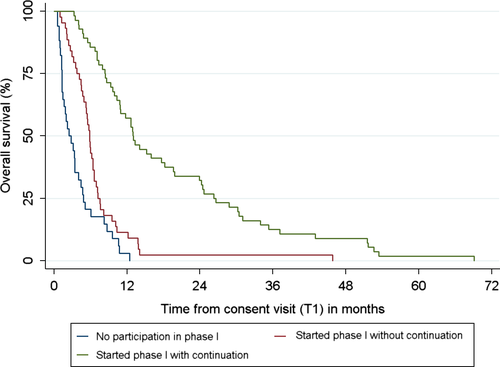

2.4.3 Overall survival

Overall, survival was analysed by means of the Kaplan–Meier method, although is of descriptive nature. Besides description of OS from the consent visit onwards, also a landmark analysis was performed from start of phase-I trial treatment (T2) until death.

3 RESULTS

A total of 135 patients of the 145 invited patients with advanced or metastatic cancer consented to this study (T1). Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Ten patients (7%) did not consent to phase-I trial participation and one patient did not fulfil the inclusion criteria.

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (year), mean ± SD (range) | 61.8 ± 10.4 (31–84) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 64 (47.8) |

| Female | 70 (52.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/living with partner | 111 (82.8) |

| Single/Separated/divorced/widowed | 23 (17.2) |

| Education level | |

| Primary education | 18 (13.4) |

| High school or college | 78 (58.3) |

| University | 34 (25.4) |

| Other or unknown | 4 (2.9) |

| Time since diagnose (year), mean ± SD (range) | 2.3 ± 2.2 (0–16.8) |

| Tumour Classification | |

| Bone and Soft Tissue | 9 (6.7) |

| Breast | 9 (6.7) |

| Gastrointestinal | 51 (38.0) |

| Gynaecological | 29 (21.6) |

| All others | 36 (26.8) |

| WHO performance status | |

| 0 | 24 (17.9) |

| 1 | 105 (78.4) |

| 2 | 3 (2.2) |

| 3 | 1 (0.7) |

| Phase-I trials | |

| Single experimental agent | 76 (56.7) |

| Combination therapy, with 1 approved agent | 58 (43.3 |

| RMH prognostic score | |

| 0 | 77 (57.5) |

| 1 | 47 (35.1) |

| 2 | 9 (6.7) |

Note

- SD: Standard deviation; RMH: Royal Marsden Hospital; WHO: World Health Organization.

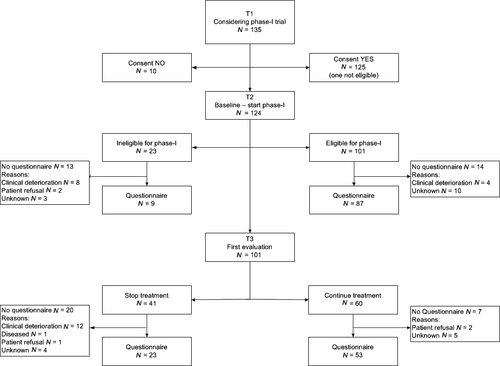

A total of 124 patients started the screening of whom 101 (81%) were eligible for trial participation (Figure 1). At baseline (T2), 96 of the 124 screened patients completed the questionnaire. This includes both eligible patients (87 of 101) and ineligible patients (9 of 23).

After two cycles of treatment, the first tumour evaluation took place (T3). Fifty-three of the 60 eligible patients finished the questionnaire. Forty-one patients discontinued phase-I trial participation due to disease progression or substantial side-effects. Of this group, 23 patients completed the questionnaire, making the total of participants at this stage of the study 76 (Figure 1).

The internal consistency that is reliability of the psychological questionnaires, HHI, AACS and LoC, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha were acceptable to good (Supporting Information Table S1).

3.1 Consenting vs. nonconsenting patients

Due to the small group of nonconsenters, no statistical test was performed (Supporting Information Table S2).

3.2 Eligible vs. ineligible patients

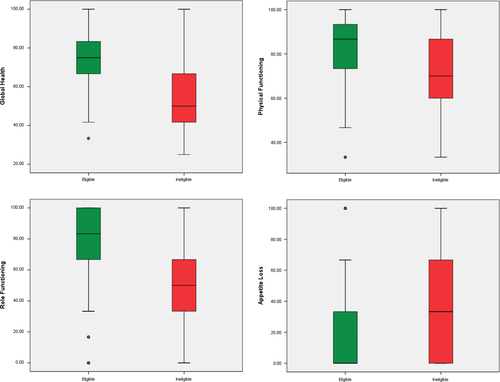

At preconsent, global health (U = 555.00, p = 0.001, r = 0.31), physical functioning (U = 637.00, p = 0.002, r = 0.28), role functioning (U = 555.50, p = 0.001, r = 0.31) and appetite loss (U = 1560.00, p < 0.001, r = 0.33) showed statistically significant differences by nonparametric testing between eligible vs. ineligible patients (Figure 2 and Table 2). Additional univariate logistic regression analyses of the preconsent data confirmed these outcomes, patients eligible for trial participation performed better on global health OR = 0.946, 95% CI [0.918, 0.975], p = 0.001, physical functioning OR = 0.959, 95% CI [0.933, 0.985], p = 0.002, role functioning OR = 0.974, 95% CI [0.957, 0.991], p = 0.003, and has a better appetite OR = 1.114 95% CI [1.035, 1.192], p < 0.001 (Table 3).

|

Predecisional (T1) Eligible at T2 Median (25–75 percentiles) N = 101 |

Predecisional (T1) Ineligible at T2 Median (25–75 percentiles) N = 22 |

p | U | Z | r | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health status/QoL | 75 (66.6–83.3) | 50 (41.7–70.8) | 0.001 | 555.00 | −3.44 | 0.31 | 0.65 |

| Physical functioning | 86.7 (73.3–93.3) | 70 (58.3–86.7) | 0.002 | 637.00 | −3.12 | 0.28 | 0.59 |

| Role functioning | 83.3 (66.7–100) | 50 (33.3–66.7) | 0.001 | 555.00 | −3.40 | 0.31 | 0.64 |

| Emotional functioning | 75 (66.7–91.7) | 66.7 (58.3–79.2) | 0.069 | 787.50 | −1.82 | 0.26 | 0.33 |

| Cognitive functioning | 100 (83.3–100) | 100 (79.2–100) | 0.255 | 1232.00 | 1.14 | 0.10 | 0.21 |

| Social functioning | 83.3 (66.7–100) | 66.7 (66.7–91.7) | 0.008 | 685.50 | −2.64 | 0.24 | 0.49 |

| Fatigue | 33.3 (11.1–44.4) | 44.4 (33.3–61.1) | 0.004 | 1469.00 | 2.91 | 0.26 | 0.54 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0 (0–16.7) | 16.7 (0–20.8) | 0.035 | 1368.50 | 2.11 | 0.19 | 0.39 |

| Pain | 16.7 (0–33.3) | 33.3 (16.7–58.3) | 0.004 | 1450.50 | 2.92 | 0.26 | 0.55 |

| Dyspnoea | 0 (0–33.3) | 33.3 (0–41.7) | 0.043 | 1355.00 | 2.03 | 0.18 | 0.37 |

| Insomnia | 0 (0–33.3) | 33.3 (0–41.7) | 0.259 | 1 244.00 | 1.13 | 0.10 | 0.20 |

| Appetite loss | 0 (0–33.3) | 33.3 (0–66.7) | <0.001 | 1560.00 | 3.67 | 0.33 | 0.70 |

| Constipation | 0 (0–33.3) | 0 (0–0) | 0.294 | 967.50 | −1.05 | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| Diarrhoea | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–16.7) | 0.186 | 1166.50 | 1.32 | 0.12 | 0.24 |

| Financial difficulties | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.500 | 980.50 | −0.68 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

Notes

- d: effect size d (0.2 = small effect, 0.5 = intermediate effect, 0.8 = large effect); QoL: Quality of Life; p-values based on Mann–Whitney U test; r: effect size using Cohen's d (0.10 = small effect, 0.24 = intermediate effect, 0.37 large effect); U: Mann–Whitney U; Z: Standardised test statisics.

- The bold items are significant at p ≤ 0.0033.

| Independent variables | OR | 95% C.I.a | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 1.054 | 1.000 | 1.110 | 0.049 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.632 | 0.254 | 1.573 | 0.324 |

| Marital status (married vs. single) | 1.216 | 0.555 | 2.665 | 0.624 |

| WHO 1 vs. 0 | 1.486 | 0.398 | 5.540 | 0.556 |

| RMS 1 vs. 0 | 1.794 | 0.704 | 4.570 | 0.221 |

| RMS 2 vs. 0 | 0.792 | 0.089 | 7.089 | 0.835 |

| Global health | 0.946 | 0.918 | 0.975 | 0.001 |

| Physical function | 0.959 | 0.933 | 0.985 | 0.002 |

| Role function | 0.974 | 0.957 | 0.991 | 0.003 |

| Emotional function | 0.976 | 0.950 | 1.002 | 0.074 |

| Cognitive function | 1.174 | 0.985 | 1.089 | 0.174 |

| Social function | 0.972 | 0.950 | 0.993 | 0.011 |

| Fatigue | 1.031 | 1.009 | 1.054 | 0.007 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 1.022 | 1.000 | 1.045 | 0.049 |

| Pain | 1.031 | 1.010 | 1.052 | 0.004 |

| Dyspnoea | 1.021 | 1.003 | 1.040 | 0.025 |

| Insomnia | 1.008 | 0.993 | 1.023 | 0.280 |

| Appetite loss | 1.114 | 1.035 | 1.192 | <0.001 a |

| Constipation | 0.987 | 0.961 | 1.013 | 0.317 |

| Diarrhoea | 1.012 | 0.984 | 1.042 | 0.403 |

| Financial difficulties | 0.995 | 0.972 | 1.019 | 0.692 |

- C.I.: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; p: p-value; RMS: Royal Marsden Score; vs.: versus; WHO: World Health performance status.

- The bolded p-values suggest statistical significant associations at p ≤ 0.0033.

- 95% C.I. for odds ratio.

- After deletion of one outlier. An OR > 1 indicates that as the independent variable increases the probability of not being eligible will increase. On the contrary, an OR < 1 indicates that as the independent variable increases, the probability of not being eligible for phase-I trial participation will decrease.

A post hoc power calculation was performed based on reported Cohen’s d effect sizes. The obtained effect sizes varied between 0.12 and 0.70 for a total of 124 patients. Given the two-sided alpha of 0.0033, the power to detect differences between the groups varied between 0.8% and 51.5%.

3.3 Continuing vs. stopping participation after first evaluation

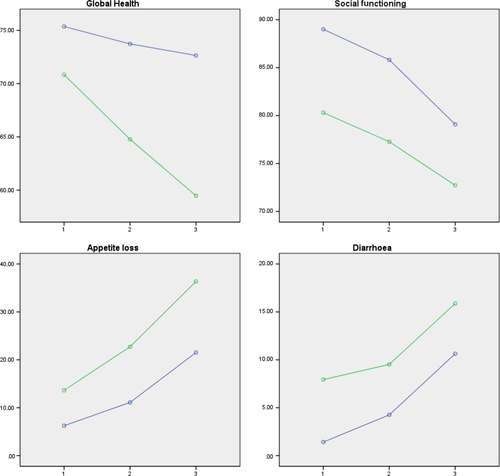

Patients who continued participation after two cycles performed better on all items from preconsent till first evaluation. The HRQoL items which significantly differed between the group of patients continuing vs. stopping after first evaluation, at all time points, and significantly differed over time in each group were global health, social functioning, appetite loss and diarrhoea (Figure 3 and Supporting Information Table S3). In all patients, a significant decline was detected in physical functioning, role functioning and cognitive functioning, and a significant increase in fatigue and dyspnoea. The symptoms which differed between the patients who could continue or had to stop were nausea and vomiting, pain and constipation. Also, financial difficulties varied between the two groups. In all patients, hope and tenacity significantly diminished over time. There was a significant difference in external LoC between both groups. All outcomes measures are described in Supporting Information Table S3.

3.4 Overall survival

The median overall survival (OS) of the whole cohort is 6.74 months (n = 134, 95% CI: 5.88–8.21). The group of ineligible and nonconsenting patients had a median OS of 2.50 months (n = 34, 95% CI: 1.31–4.01 months), patients who started a phase-I trial but discontinued treatment after two cycles had a median OS of 5.88 months (n = 44, 95% CI: 4.73–6.60 months), and patients who were able to continue phase-I trial treatment after two cycles had a median OS of 13.01 months (n = 56), 95% CI: 10.84–18.23 months). See Figure 4 for the Kaplan–Meier curves per group.

Looking at survival from start of phase-I trial treatment onwards, the median OS is 8.18 months (n = 99, 95% CI 5.98–10.12 months) for all patients who started trial participation.

4 DISCUSSION

In the patients with advanced cancer who consented to participate in a phase-I oncology trial, eligibility seems to be associated with a better global health, a better physical and role functioning, and with better appetite. Therefore, patients who could continue participation after first evaluation had better HRQoL outcomes at the start of the screening. Our findings suggest that good HRQoL outcomes are related with eligibility and prolonged trial participations. Perceived global health, appetite loss and diarrhoea make a difference in the patients considering participation both in screening and on trial. It is important that social functioning is affected in all the patients on trial. Social functioning may be under strain due to multiple hospital visits, impact of side-effects and disease-related symptoms.

In our cohort, no association was found between eligibility and the RMS or with WHO PS. The RMS was developed to predict patients’ survival in phase-I trials and might serve as a selection tool. As such it might help clinicians to decide whether a patient should participate in a trial or not (Arkenau et al., 2008). Suggestions are made to exclude patients with a RMS of 3 from a phase-I trial in view of their limited life expectancy (Garrido-Laguna et al., 2012). None of the patients in our cohort had a RMS higher than 2 at preconsent. Nevertheless, a substantial part of the patients was not able to start a trial. HRQoL might be a suitable tool to discern patients at risk. An advantage might be the fact that patient-reported outcomes lack the observation bias from clinicians. It is possible that both the RMS and HRQoL scores may complement each other in predicting outcomes of patients at risk for screen failure or early deterioration in clinical trials. There may be ground for further prospective research in this matter. In addition, the HRQoL might serve as a basis to guide for palliative care and in decision making towards trial participation.

In the groups of patients who had to stop after two cycles of experimental treatment, appetite loss and symptoms like nausea and vomiting and constipation had a negative impact on their experienced quality of life. Furthermore, increased fatigue, decline of physical, role and cognitive functioning, which were found in all participating patients, are the most common health problems among patients with advanced cancer participating in cancer trials (Ferrell et al., 2017; Osoba, 2011). Rouanne et al. saw a significant decrease in physical health but not in mental health in their cohort of participating patients (Rouanne et al., 2013). Patients who could continue after two cycles may have had less aggressive deterioration of their disease or experienced clinical benefit. Earlier research showed that the patients who continued could have experienced fewer side-effects of the investigated agents, since they had fewer symptoms of their disease to start with (Anwar et al., 2017; Treasure et al., 2018).

Our findings show that trial participation affects hope and coping strategies. During trial participation, there was a decrease of hope in all patients. This could be associated with a drop in experienced global health, since global health and hope were correlated at preconsent (Van der Biessen et al., 2018). The maintenance of quality of life is an important factor in staying hopeful. Patients participating in a phase-I clinical trial put hope for treatment above quality of life (Godskesen, Nygren, Nordin, Hansson, & Kihlbom, 2013). In our study, the patients who stopped participation after two cycles coping strategies changed. They showed a decrease in tenacity (diminished holding on to treatment) and an increase in external locus of control (giving up on control). It is possible that the fact that patients have to end trial participation, often seen as last resort, may help some of the patients face a next step in their disease process. They no longer need or are able to be in control of their disease and can focus on symptomatic relieve.

The OS in our group of patients who started participation was 8.18 months. Earlier reports of OS in phase-I clinical trials showed OS rates varying between 9.9 (Arkenau et al., 2009) and 10.5 (Chau et al., 2011) months. Variations in research modalities, group size, heterogeneity of tumour types, or baseline condition may explain these variations in survival. The description of the several survival times is informative and can be useful for patients and clinicians in the decision making process.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. Due to clinical deterioration, patients’ refusal, trial burden, or unknown factors, not all patients completed the questionnaires at baseline or after first evaluation. This could have influenced the outcomes of our study. Furthermore, the small sample size prevented us from making firm statements about the outcomes, and was unable to perform multivariate analyses. Therefore, we limited the scope of our outcomes to the most significant outcomes. A larger cohort could have provided us with more rigorous data, to confirm the prognostic role of HRQoL. One of the strengths is that data were gathered from patients before initial consent to a phase-I trial. Another strength is the prospective character of the measures HRQoL, hope and coping strategies. This enabled discussion of the prospect of trial participation, not only based on empirical evaluations but supported by systematic observations.

4.2 Clinical implications

Informing patients about the consequences of trial participation on their quality of life, hope and coping may help them make a well-informed decision. During the discussion of trial participation, it should be kept in mind that hope will influence patients’ perception, since patient’ hope is high (Catt, Langridge, Fallowfield, Talbot, & Jenkins, 2011; Godskesen et al., 2013; Moorcraft et al., 2016; Van der Biessen et al., 2018).

The maintenance and support of HRQoL and hope is a challenging objective in the care for potential phase-I patients. Our data shows that there is a need for improved palliative care for phase-I patients. Patient-reported outcomes prior and during trial participation might give guidance in applying the right palliative care interventions at the right moment. The potential benefit of measuring of PROs like HRQoL and additional integration of palliative care in this group of patients seems, although preliminary, evident (Ferrell et al., 2017; Reeve et al., 2014). PROs can be a tool to identify the patients at risk of failing phase-I trial screening and may guide communication about goals, needs and values. (Ferrell et al., 2017; Yang, Manhas, Howard, & Olson, 2017). Further prospective exploration is needed to show if measuring PROs improves patients’ outcomes and research results, and thus, future patients’ perspectives.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study was approved by the institutional review board METC 11-106 and registered at the Dutch Trial Registry NTR3354. The study is conducted to conform the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Professor Dr. Carin van der Rijt, for her advice, and Kevin Breedijk, at that time student at the Leiden University of Applied Sciences, for his contribution to the data collection.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) have no potential conflict of interest.