Service Design Proliferation – Dilemma at IT Organizations

Abstract

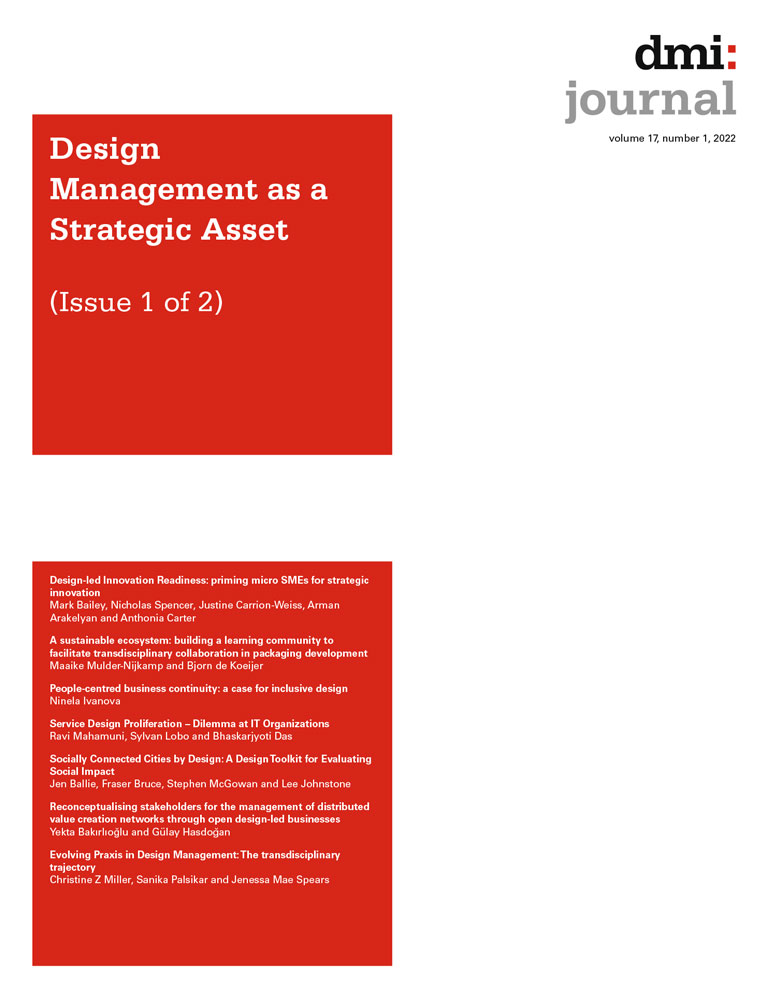

Organizations are transitioning from a product mindset to services as their primary customer offering. Service organizations today have complex processes spread across physical and digital spaces involving several stakeholders. IT organizations help these organizations by building products and services and providing advisory to achieve their strategic objectives. IT organizations are hence well-positioned to introduce this shift towards a service mindset and encourage the adoption of service design. IT organizations need to first decide whether they want to proliferate service design. However, there is a predicament about how to approach this - should they start by designing the services for their customers first, or focus on their own organizational internal services? Once they decide it then next dilemma is about whether to follow top-down or bottom-up approach. We have utilized an ‘Inside-out’ approach for proliferating service design to address these dilemmas. The approach of ‘inside-out’, in essence, is about gradually proliferating a new process by experiencing its benefits within the organization first and then subsequently applying it to their customers outside the organization. In this paper we advocate the mix of top-down or bottom-up approach for the proliferation of service design.

Introduction

Design is transitioning from a product-oriented process to solving complex problems entwined in the socio-cultural, political, and environmental aspects (Manzini, 2016; Buchanan, 1992). The changing global scenario of depleting resources and increased demand for customer experience has made organisations of today look beyond growing ‘consumerism’ towards more sustainable and ecosystem-centred business models (Ghobakhloo, 2019; Frank, Mendes, Ayala, & Ghezzi, 2019). There is a growing recognition among service organisations that today's complex problems are difficult to solve in isolation. To create products and service systems that are meaningful, relevant, and helpful to all users and stakeholders, design must focus on the needs, capabilities, and values of the service customers (Junginger, 2017) and stakeholders.

Organisations are progressing towards Industry 4.0, the new phase of the industrial revolution that enables advanced digitalisation to automate and optimise operating and management processes with decentralised systems of production and innovation and increasing focus on human experience (Lasi, Fettke, Kemper, Feld, & Hoffmann, 2014). Technological development and increased accessibility also facilitate organisations to employ a culturally diverse workforce to synchronously work across geographies and provide experiential products and services to a global pool of customers. This spread and accessibility to the rapidly developing digital technologies have further accelerated and enabled designers to collaborate more closely with users and other stakeholders. Thus, also promoting design as a plural and participatory process to create new cultural meanings and practices, generate experiences (Escobar, 2018; Manzini, 2016; Julier, 2006).

We posit that IT organisations are uniquely placed in bringing in a shift towards a service mindset and encouraging the adoption of service design. IT organisations and consultancies help their client organisation's businesses by building products and services and providing advisory to achieve their strategic objectives. Unlike other service organisations or consultancies which focus on specific aspects (such as legal, training, finance, transport, etc.), IT consultancies are often involved in a broader scope of projects which are customer-facing products or services. Their engagement is for the long term, including the inception, implementation, maintenance and retiring of the project. They can play a significant role in shaping up the end-user experience and customer satisfaction, and thus value the adoption or competencies in Service Design. Service Design competency can provide a competitive advantage to the business of IT organisations while benefitting the client organisation and customers.

While many large organisations have embraced design, design thinking, and service design, effort is needed to make it mainstream (Covino & Bianco, 2018). There are tensions in perceiving the tangible business benefits of design (Sheppard, Sarrazin, Kouyoumjian, & Dore, 2018). There are challenges which act as roadblocks to the adoption of service design. For example, in a large multi-cultural IT organisation, service design activity is often susceptible to organisational structures, politics, culture, informal opinions, and knowledge accessibility restrictions (Blomkvist, 2015). The existing organisational settings often create work silos, further hampering sustained collaboration between actors (Atvur et al., 2015).

Given these challenges, the move to adopting service design is a big cultural and mindset shift for IT organizations. This can be a dilemma to the organization given their existing successful operation model, and the effort that may be required in reskilling and making it part of their offering. Once IT organisations decide to adopt the service design approach, the next dilemma is about how to go about it. Besides the services offered to the customers, every IT organization has internal employee services. Organisations have the opportunity of using service design for both the types of services. Organizations need to deliberate and decide whether they should start helping their customers first and then reimagine the internal employee services, i.e., an ‘outside-in’ approach—or, whether to apply the service design approach the internal employee services, experience the value first, and then start proliferating to their customers, i.e., an ‘inside-out’ approach. Both these approaches have their own pros and cons. We introduce the idea of an ‘inside-out’ approach to proliferate service design through a two-step approach—first introducing service design internally within large organisations such as IT organisations and eventually outwards in their client organisations. This approach may be suitable for other service organisations and consultancies as well. However, we have limited ourselves to the context of an IT consultancy being part of one.

The next dilemma is about how to implement it—through a bottom-up or top-down approach. We propose introducing service design within an organisation through a bottom-up and top-down approach while manoeuvring this change using the CraftChange Behavioural progression framework (Mahamuni, 2020). The CraftChange Framework is an integrated framework for designing services for behaviour change.

With the ‘inside-out’ approach of proliferating service design knowledge, we believe employees would beget higher confidence in the impact of service design and would become more effective and efficient to take up complex service design challenges for customer services. We argue that the successful proliferation of service design in the organisation for internal services will facilitate employees to adapt service design methodology for complex scenarios and further learn its implications through real-world projects. This paper discusses the usefulness of an ‘inside-out’ service design approach driven by behavioural science for internalizing service design approaches and sustaining its practice in a large IT organisation. We further discuss our recommendations on various service design activities that can facilitate its proliferation.

Introducing Service Design at IT Organizations

There are several dilemmas encountered for service design proliferation at IT services organizations, given the organisational and cultural diversity. IT organizations are large in terms of the number of employees, are distributed globally, and its workforce have been fluent in their traditional processes of innovation. In this section, we highlight the different dilemmas we observed in the service design proliferation journey in the IT organization where we work as well as from literature.

Dilemma about the need of service design for organizations

Service organisations today have complex processes spread across physical and digital spaces involving several stakeholders with entwined interaction channels and enabling user access to both human and digital touchpoints. Service Design is an approach to design for services with a human-centric holistic focus, choreographing various elements—processes, technology, interactions towards co-creating value for all stakeholders, including service users, staff, and the business.

Service design and design thinking are gaining recognition in organisations, especially for employee experience (Bertolotti et al., 2018) and business transformation (Auricchio et al., 2018). Service design is an apt approach for developing experience-centric services (Zomerdijk & Voss, 2010). It seems necessary that IT organisations start adopting service design for improving the customer experience of their clientele's services. Employee experience facilitates customer experience (Morgan, 2018) by appreciating productivity and improvement in overall interaction quality, promoting organisational and financial success (Naseem et al., 2011). Organisational services need to facilitate a work environment that encourages employees to give quality outcomes and enables them to design better customer experience. Catering to employees' needs and concerns through organisational services acts as a facilitator to higher employee engagement (Saks, 2006), productivity (Globoforce & IBM, 2016), commitment, and improvements in retention and turnover.

The CraftChange Empathy Square construct also acknowledges the importance and role of the human touchpoints, i.e., the service staff while delivering the services to the end-users (Mahamuni, Anna Meroni, & Punekar, 2019). Most service staff are employees of the service provider organisation. For effective and sustainable service design interventions, concerns of service staff need to be addressed along with the concerns of the service users.

It was clear that we need to focus on the employees and stakeholders within the organisations first. They should get first-hand experience of the value of service design by improving the employee experience to bring out customer-centricity. We felt that the most compelling way to introduce service design acceptability would be to address internal employee services using service design while adapting the tools and techniques for the organisational context. On the other hand, the inside-out approach delays applying the service design for their customer organisations, leading to loss of revenue, or missed business opportunities. It is also true that directly applying service design approach for external clients without first experiencing it internally may have service quality issues. Hence, IT organisations need to deliberate and decide which approach to use.

However, there are challenges in the proliferation and wide-scale adoption of service design approaches in an organisation—both for internal employee services and introducing it for its clients. For instance, a dedicated function for service design is often missing. Designers may only be invited at specific moments rather than from the start (Auricchio et al., 2018). Service design is sometimes seen as merely an approach to address complaints rather than proactively and holistically designing for the customer (Blomkvist, 2015). Organisational roadblocks can also affect the implementation of service design solutions. There are risks involved in legal, business, brand, and operational cost. Organisational context can often lead to communication breakdowns, disengagement, stress, and slow progress. Further, misaligned values and priorities between designers and stakeholders, less power and control of resources with the involved stakeholders, ineffective communication strategies, and lack of buy-in from key stakeholders affect service design and implementing solutions (Salibian & Pratt, 2018).

Imbibing service design - an organizational change

Organisational change is a continuous and cross-organizational process of experimentation and adaptation at multiple levels in the organisation (Burnes, 2004). The transformation of organisational culture drives organisational transformation, and employees need to be supported by the knowledge, skills, and motivation to adapt to new changes. Organisational culture has a critical influence on the overall wellbeing of employees. Organisational culture is interpreted in the literature as patterns of shared values and assumptions that employees showcase as adopted values and collective behaviours (Williams, Kern, & Water, 2016). A positive culture promotes social participation, teamwork, and relationship satisfaction, whereas a negative culture can promote internal competition and sometimes avoidance and disengagement. Hence, it is essential that organisation culture nourishes rich interactions and drives a positive employee experience. Behavioural science provides a useful platform for bringing organisational change (Foster, 2017) by promoting new habits among its employees. However, we do not find a behavioural science approach in literature to facilitate a service design transformation journey in an organisation.

Current approaches for service design proliferation

Amidst internal and external opportunities and threats, organisations leverage change in processes, people, and organisational culture to become more effective in achieving their goals. Covino and Bianco (2018) suggest that service design must be adapted to make it available to non-design practitioners. It can be achieved by making the language and design methods more accessible, embedding service design into traditional activities, and co-creation workshops. They suggest that the service design practice needs to be developed both inside and outside the organisation, by fostering a global community of designers and practitioners, and through cross-regional training.

Katz (2015) proposes seven stages for diffusing a design and innovation culture in organisations: 1) Scepticism, 2) Tokenism, 3) Curiosity, 4) Experimentation, 5) Commitment, 6) Pushing boundaries, and 7) New normal. They suggest various ways to progress across the stages of maturity with approaches like investing in building awareness, inviting experts, running live demonstration projects and hackathons, and developing network advocates for service design. Capgemini Trust (2018) propose a four-pillar framework, focusing on highlighting the vision and principles; sharing practical approaches, tools, and methods; sharing knowledge through communication and training, and managing the program to keep it on track.

Arico et al. (2017) suggest a framework for facilitating service design based on their experience in a telecommunications corporation. They highlight the resistance which arises as the service design approach is very different from the traditional business process, which has clear goals and steps and is profit, technology, and efficiency centred. On the other hand, Service Design is an exploratory and iterative approach, focusing on human-centeredness, holism, empathy, and co-creation. The differing priorities lead to challenges in execution, questioning legitimacy (not perceived as serious exercise), commitment (room for flexibility and uncertainty), and resources (deliverables and outcomes unfold along the design process, and are not upfront). Considering these challenges, the researchers arrived at a three-part framework to diffuse service design into the organisation to address each of the challenges—i.e., evidencing customer insights, validating business concepts, and engaging organisational actors - through research, visualisation, and prototyping. These approaches also lack the lens of behaviour change and we believe that the service design proliferation needs to be looked from organizational behaviour change perspective.

Our approach for organizational change

While we align with the many approaches to introducing service design to the organisation discussed above, we believe it is necessary to develop employees' motivation and competency toward service design actively and calls for a cultural change within the organisation.

For proliferating service design in organisations, we utilize an ‘inside-out’ strategy (Mahamuni, Lobo, & Das, 2020) (Figure 1)—where ‘inside’ refers to internal employee services and ‘out’ refers to the products or services meant for external customers. By gradually building competency, tools, and exposure to service design internally, the organisation and its employees can be empowered to apply it at scale to its business clients, passing on the value to their business. As shown in Figure 1, initial commitment from top management for service experience design is very critical to start the proliferation in the organisation. Their focus on creating a conducive environment by allocating the required resources and opening avenues to experiment is key to success. This is followed by systematically changing the employee behaviour by increasing their awareness of service design and helping them experience its benefit which helps to internalise it. In the end, in concurrence with the top management, it can be taken out of the organisation to help their customers.

We consider that adopting the service design methodology is a behaviour change from an organisation employee's perspective. As per the MAT model (Fogg, 2009), to make this behaviour change happen, we need to motivate the employee, build employee's and organisational abilities, and provide the triggers at the right time. The proliferation of Service Design in the organisation is an organisational transformational journey which influences the organisational culture (macro-level behaviour) along with the behavioural change of its employees (micro-level behaviour). It is a progressive journey for an organisation as well as for its employees. As per Buddhism (Buddhism 500 BC) to internalise anything it goes through the three kinds of wisdom: (the learning process) ‘suta-maya panna’-wisdom gained by listening to others; then ‘cinta-maya panna’-intellectual, analytical understanding and then ‘bhavana-maya panna’-wisdom based on direct personal experience. This inspired us to look at the proliferation problem as a behaviour change progression, starting from making people aware until they experience it and then internalise it. We explored CraftChange Service Design Framework for sustained behaviour change (Mahamuni, Khambete, & Punekar, 2019; Mahamuni, 2020) for the required rigour and guidance to go through this transformational journey.

Internalizing and sustaining service design practice

Effective information gathering, communication, and learning are vital organisational activities that facilitate organisational change in dynamic and uncertain environments (Burnes, 1996, p. 14). Revans (1998) further argues that learning occurs best when it is directly related to work and action that an employee is engaged. Hence, the proposed inside-out approach aims at first focusing on internal employee services. Burnes' (2004) change management framework argues that a successful culture change in the organisation emerges from a change in the organisational environment rather than a deliberate top-down approach. The framework also highlights the importance of guidance from senior leaders of the organisation to facilitate the emerging transformation. It is imperative to state that a top-to-bottom approach to influence organisational culture requires detailed planning and demands employee allegiance to the same. However, a bottom-to-top approach enables employees to iteratively create an organisational culture that they feel co-ownership of, e.g., Muhammad Yunus's ‘Grameen Bank’, a scalable village banking model in Bangladesh which grew as collective creative innovation of the villagers. ‘Grameen Bank’ also exemplifies itself as a successful business model which operates and innovates with a strategic community-based intent (Simanis & Hart, 2011). Therefore, our proposed ‘inside-out’ service design proliferation approach tries to incorporate the benefits of both top-down and bottom-up approach.

Driving Behavioural Change through Bottom-up approach

Employees within the organisation should experience the value of service design first, by encountering enhanced internal employee services developed through service design in-house. This approach would help demonstrate the impact and value of service design. The involved stakeholders should actively aim to impress and motivate employees through successful cases of service design internally and triggering them to adopt service design proactively. Success in-house would lead to confidence and competency development, allowing service design to flow to customers of the organisation. The learnings, experience, and tools developed could enable a firmer footing for designing services and experiences for customers.

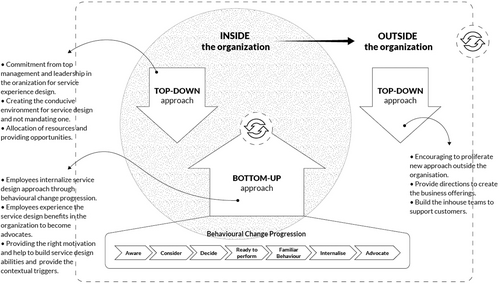

The ‘inside-out’ approach proposes to attempt this shift using the CraftChange Behavioural Progression framework (Figure 2) to gradually guide the transition, primarily encouraging employees in a bottom-up manner, while also incorporating a top-down approach to facilitate the transition.

The CraftChange Framework (Mahamuni, 2020) is an integrative framework for Service Design for sustained behaviour change. At the heart of this framework is the CraftChange - Empathy Square and the CraftChange - Behaviour Change Progression Model, which provides the required theoretical foundation. The other components of this framework are various canvases and cards, and the process of using these components in the Service Design life cycle. CraftChange - Behaviour Change Progression model (Figure 2) depicts the journey of a user from an unaware stage until it becomes the advocate of the intended behaviour change. The Empathy Square enables designers to think from the perspective of relevant stakeholders to address their concerns. It also enables the Service Designer to be mindful about environmental concerns along with the concerns of human touchpoints or service staff. The Behaviour Change Progression model aids the service designer to conceptualise user services and other interventions for their intended behaviour change progression.

As per the CraftChange Behaviour Change Progression model (Figure 2), we wanted employees to go through the journey of becoming aware, getting engaged, and getting familiar with the benefits of service design by experiencing it. CraftChange framework advises to first consider the current context by studying existing interventions based on CraftChange Current Intervention Cards. We have outlined this mapping of the current context supporting employees to be innovative, design-centred, and customer-centric, if not wholly service design-oriented in Table 1.

| CraftChange Current Intervention cards | Current interventions supporting innovation, design-centricity, customer-centricity, service design |

|---|---|

| Persuasive interventions | A Business 4.0 and Industry 4.0 transformation narrative; Innovation competitions with special categories for design and service design – allowing teams who have designed services and processes to participate even if they have not followed the service design process as understood by the design community. |

| Incentivization interventions | Learning platform with learning metrics mapped to redeemable points - on the learning portal encouraging to learn deeply in their domain and across other areas to have well-rounded awareness. There are design courses available, with micro-learning platforms. |

| Coercive interventions | Mandated target learning metrics to achieve |

| Training interventions | Design thinking workshops for employees and support functions like Human Resources (HR); Agile methodologies |

| Restrictive interventions | - |

| Physical aspects of the environment | Agile workspaces supporting improved collaboration |

| Role model interventions | External mentors and advisors |

| Educational interventions | Invited talks from experts; video screenings; encouraging and supporting employees for higher education |

| Leveraging networking interventions | Building a research partnership with premier design institutes and encouraging employees to join design forums and conferences |

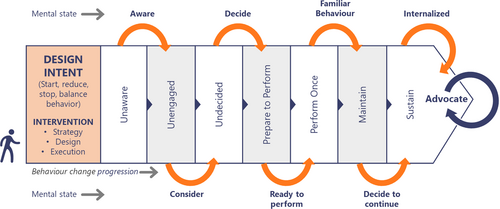

After understanding the current context, we embarked on a journey of developing internal employee services. To have the best impact internally and build awareness and experience of service design, we chose services across the entire employee journey in organisations—right from job search to recruitment, and onboarding, and further long-term assimilation and retention. We initiated various service design projects over four years in the Human Resources (HR) and talent management space. These projects were chosen based on the number of service users involved, availability of stakeholders for collaboration, resource allocation for experimentation, and its projected impact on organisational business. The projects and the participating teams are indicated in Figure 3. The design research team, along with the HR, were the primary anchors of the projects. They were responsible for managing the participation of service-specific stakeholders, organisational function groups, and knowledge transfer across groups and projects. The exact number of participants varied across projects and time, with approximately 3–5 designers, 3–6 HR, and representation from at least one HR leadership, 1–2 admin, and 3–15 employees who occasionally participated via interviews or validation exercises.

Using the CraftChange Behaviour Change Progression model (Figure 2), we designed interventions for service design knowledge acquisition and proliferation during each phase of the employee journey (Figure 3). The design intent was to change the behaviour of organisational employees from being unaware of service design to becoming advocates of the service design process. In the advocate stage, employees of IT organisations start advocating the service design approach to their customers who are the organisations in various other domains like banking and finance, healthcare, etc. Before starting the proliferation process, we had engaged in initial kick-off and domain sensitization sessions with stakeholders to assess the current state of service design knowledge and determine their current behavioural stages (for example: being unaware) in the behaviour change progression model (Figure 2). This further helps to identify the subsequent behavioural stages for which interventions are needed to help employees progress towards being advocates of the intent, i.e., proliferation of service design in the organization.

For example, in the employee recruitment and onboarding study (Figure 3) we used various strategies at different stages in the progression framework. We used mechanisms to generate interest and “Awareness” with the HR by demonstrating the successes of case studies including the Employee Referral project (Figure 3) (Mahamuni R., Khambete, Mantry, Das, & Varghese, 2016) including demonstrating engaging prototypes. We involved them in design workshops to give a first-hand experience to “Consider” and “Decide” to proceed with the service design approach. These initial engagements included kick-off and problem discovery workshops with varied stakeholders and use of tools like personas and customer journey maps. Through many more such workshops and ideation sessions, the participants were then “Familiarised” with the approach. All engagements were consciously designed to engage and help the participants appreciate the process.

Impact of ‘Inside-Out’ Approach for Service Design Proliferation

During the ‘inside-out’ approach, we engaged with several employees across various service design projects. These internal service design projects provided the select employees with the opportunity to define the problems for their context, conduct user research, ideate, and prototype service concepts. We surveyed few employees from these projects to understand the impact of the service design approach in their day-to-day project work. The survey objective was to understand the change in the overall perspectives and approach that service design knowledge had generated among the participants during and after our project engagement. The survey included questions for quantitative and qualitative data and was piloted before sending it to various project owners and participants through the internal communications channel of the organisation. The respondents were selected through purposive sampling where 25 participants were recruited based on their engagement in internal service design projects. We received 17 responses which were considered for the following analysis.

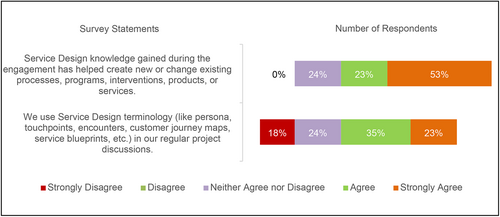

The internalisation of Service Design approach

As summarised in Figure 4, in the first part of the survey, 76% of participants (13 of 17) felt that the service design knowledge gained through the exercise helped them change their overall perspectives towards new initiatives within their work setting. The rest of the participants had a neutral outlook. Around 58% of participants acknowledged that they had started using some service design terminologies such as personas, customer journeys, and touchpoints in their day-to-day interactions at work. In comparison, 18% indicated that they did not. The results indicate that the participants are in the early phases of internalising the service design process and would require further facilitation to do the same. Further responses, shown in the next section, highlights the need to focus on specific constraints and concerns that stakeholders face in their progress from awareness to engagement.

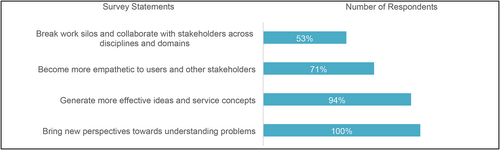

Benefits from service design engagement

We also sought feedback on what the participants perceived as the value of the service design process (summarised in Figure 5). All participants highlighted that the process was influential in bringing new perspectives in solving the problem at hand and that it helped in arriving at novel ideas. However, the participants were found struggling with internalising cross-disciplinary collaboration and transitioning from existing structures of domain-based work silos. While there is still an opportunity to improve cross-silo engagement, it is encouraging that near half the participants felt the process encouraged them to engage. Participants were also found gradually being more empathetic to the various stakeholders involved in a service design. This highlights a challenge as well as opportunities to design useful tools and processes to capture stakeholder empathy in an organisational setting and internalise it through the design approach.

“I was handling this function for 5+years but got to know the new perspectives which provoked my thought process. It was a game-changer model for the ____ process of our organisation. Understanding the problem statement by the generation of more ideas resulted in new perspectives that have benefited the management and the associates. Empathy was the underlining factor in this whole initiative.”

These findings suggest that the participants could perceive and gain considerable value from the service design approach and were willing to utilise it in future initiatives. The participants also highlighted that it was a learning experience and appreciated the ideation process and use of tools for ideation such as personas and service design patterns:“The service design process breaks each level separately and gives a view on the impact on the value chain of the entire process.”

“We learnt more about persona and how it should be used for generating ideas for a given problem.”

“Concept of service design patterns helps in lateral thinking and also in discovering any blind spots or aspects of the service that may have been overlooked.”

Further proliferation of Service Design approach

We also assessed how ready the participants were to advocate the process to others. The Net Promoter Score (Reichheld, 2003) values are shown in Table 2, and it is higher than 50 for promoting the process for internal as well as external initiatives of the company. The Net Promoter Score (NPS) calculates the difference between the percentage of promoters (who rates 9 or 10 in the scale of 0 to 10) and percentage of detractors (who rates between 0 and 6 in the scale of 0 to 10) to generate an index of net promoters. Although the score is widely used in organisations, there is a growing debate on the effectiveness of the net promoter score as a definite measurement of customer satisfaction (Zaki, Kandeil, Neely, & McColl-Kennedy, 2016; Kristensen & Eskildsen, 2014). Nevertheless, we found it as a suitable approach as our exercise was to primarily inquire if our ‘inside-out’ approach was useful and effective enough for stakeholders to understand and recommend the service design process to other organisation customers.

| Survey Question | Promoters | Passives | Detractors | Net Promoter Score® |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Would you like to recommend and proliferate service design knowledge to TCS internal teams from other domains and business units? | 65% | 29% | 6% | 59 |

| Do you think the service design process can be recommended to external customers of TCS? | 59% | 35% | 6% | 53 |

The numbers of passives and detractors shown in Table 2 indicate that the ‘inside-out’ approach is working within the organisation but there is scope for further improvements in building better acceptability to the process. One participant also suggested tighter integration with the technical implementation to make the outcomes move to the last-mile, reaching the end customer. We believe that improving and developing well-rounded tools and processes will immensely bring out the value impact of service design in the organisation.

“Service design needs to market their approach much more in __, we are helping by word of mouth, but it needs to be more visible in social media and also active participation in customer or prospect pilots”

“…Could explore the possibility of building a consulting offering around Service Design in collaboration with ___”

Reflections

Reflecting on the three dilemmas faced during this proliferation, it was evident that involvement of various stakeholders was crucial while deliberating on each dilemma. It was observed that if we consider service design as not just a process, but a natural way of doing things, it helps teams to look at the problem more holistically.

In our case study, designing for various internal services paved a path for proliferating service design within the organisation. This enabled and empowered the employees in the organisation to adapt the service design approach for developing new services. It also helped in developing the overall perspectives towards innovation. Demonstrations of the various creative solutions and engaging prototypes that we developed during the projects created a vibe and interest among other employees, internal departments, and client-facing business units – which included HR products, airport services, and public services. While the value of service design is still being discovered, sufficient interest was generated, which led to initial engagements and discussions over using the service design approach in client projects.

The service design approach to derive insights and build creative solutions that considered the concerns of all stakeholders was appreciated. It was viewed as promising for business, as a service design capability could bring in a competitive advantage to existing products and support client projects. We found that we could extract adequate learnings through internal service design studies to support client-facing projects or servitisation of products. In this ‘inside-out’ approach, along with continuous reflection, we can build and adapt service design methods and tools to build the service design capability of the organisation.

The ‘inside-out’ approach to service design proliferation is the congruence of top-down and bottom-up approaches. Initial efforts were required to get leadership buy-in to approve and experiment with such an unfamiliar approach. Initial success stories helped to enable it. Since the organisation is advocating the service design proliferation and investing in designing the internal organisational services, it shows the organisational top management commitment. It resulted in the allocation of all required resources as seen in the Employee Referral as well as Employee Recruitment and Onboarding services where non-traditional approaches and solutions were welcome.

Further top-down approaches such as collaboration with learning and development departments to develop the techniques helped reach out to others who are interested and ready to try out service design. The bottom-up drive of employees comes due to their own experience of organisational services and realisation of its benefits. This was prominently reflected in all our projects where the stakeholders had eventually developed a fair understanding of design jargon and mindset and were ready to try the techniques in other initiatives. Making use of internal forums like conventions and competitions to highlight such work and garner interest was also useful. As a result, the ‘inside-out’ approach was observed to provide a better understanding of the social and business value impact of service design approaches to the customer as well as internal projects and facilitate the proactiveness of employees towards cultivating a design-led culture in the organisation. It automatically helps to change the mind-set at ground level with motivated employees in line with the organisational goal of service design proliferation. It becomes a win-win situation for top management and employees.

Since we tried this approach in an IT organisation, most of the participants of the participatory design team were with a technology background. This exercise was introductory for them. Generally, they get entangled into developing only technology solutions. However, this exercise helped them look at the problem from a different perspective, a more holistic one, and allowed them to focus on value co-creation and value propagation by different means and avoided the fixation on a technology solution.

In the journey of designing internal services for employee experience, the ‘inside-out’ proliferation of service design approach helped the employees better understand the intent and concerns of their business customers and the stakeholders involved at all levels. The business customers communicated their appreciation and welcomed the change in the problem-solving approach that the IT company is not merely providing discrete IT solutions but are looking at the problems holistically. This impression opened more opportunities by broadening the scope of the project for the effective implementation of the change in focus. However, it is essential to note that the ‘inside-out’ approach aspires holistic change and hence is preferable in a situation when there is the lead time for the organisation to take innovations to the market so that the organisation can focus on proliferating desirable change to its workforce before approaching external clients. Several constraints also determine organisation's readiness in adapting the ‘inside-out’ approach – (a) size of the organisation, (b) awareness and current state of internalisation of the design mindset and process, and (c) availability of resources and time. As also discussed in Figure 1, commitment from the top management of the organisation and allocation of necessary resources to its workforce is critical to begin adaptation of the ‘inside-out’ approach in the organisation. Further, the organisational culture should foster an innovation mindset, provide timely support throughout the employee's journey to help them internalise and become advocates of service design. The organisation also needs to facilitate internal systems to offer business opportunities for its employees to proliferate their learnings and experiences outside the organisation.

Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we deliberated the three dilemmas and discussed an ‘inside-out’ approach by addressing employee-centric services first to proliferate service design in the organisation. We explored different ways of service design collaborations, leveraged tacit knowledge of employees, and approached the service design proliferation exercise as a behaviour change problem. With ‘inside-out’ approach as a guide, we have been successful in garnering interest and facilitating the impact of service design within the organisation through projects like employee referral, onboarding, and integration services. The initial work has proliferated engagements with clientele projects to design and develop experience-centric-services.

During our journey, we observed a gradual increase in visibility, interest, and engagements for service design with other business units in our organisation, which is primarily attributed to our ongoing work in the domain of employee services. This enforces our belief that ‘inside-out’ approach can be powerful in demonstrating the impact of service design and motivating the organisation to adapt its approaches. In our journey, the ‘inside-out’ approach is applied in a large IT organisation, but we do believe that it is applicable and beneficial to non-IT organisations as well. The approach of ‘inside-out’, in essence, is about gradually proliferating a new process by experiencing its benefits within the organisation first and then subsequently applying it to their customers outside the organisation. Hence, we believe that the proposed approach can be useful to proliferate any new process in the organisation but needs further exploration.

Biographies

Ravi Mahamuni, is Principal Scientist and Design Research Head at TCS Research. Over his twenty-seven years of industry experience in diverse roles, garnered rich experience in both design, technology and management. He believes in technology as an enabler while humanizing the services. His research interests cover aspects that inform design for change, service design for scale and how service designers can facilitate the change that people and communities desire.

Sylvan Lobo, is a scientist at TCS Research, with over 13 years of experience of research in the field of Design. His current focus in on adapting Service Design methodologies for the orgnization. His design interests also include qualitative studies, and HCI for less-literate and visually impaired users. He is an author of over 17 research papers and has 22 patent grants. He is a graduate of IDC School of Design, IIT Bombay and a Master of Computer Applications, Goa University, India.

Bhaskarjyoti Das, is a service designer and researcher at TCS Research India. His work primarily focuses on development of new design strategies for consulting clients, and proliferation of service design practice in business organizations. The range of his academic and professional interests include Service Design, Systems Thinking, Design Research, Design for Circular Economy, and Strategic Design. He is a BTech from IIT Gandhinagar and M.Des. in Product Design from NID Ahmedabad, India. He was awarded fellowship in Circular Economy by Ellen McArthur Foundation, UK.