A sustainable ecosystem: building a learning community to facilitate transdisciplinary collaboration in packaging development

Abstract

Sustainability-related developments become a differentiating factor in development processes. An area with a strong focus on sustainability-related issues is packaging. In current packaging development processes, stakeholders focus on solving sustainability issues within their own boundaries. However, the complexities surrounding circular packaging can only be overcome by transdisciplinary collaboration. ‘Traditional’ collaboration shows to be incapable of overcoming packaging-specific complexities. Therefore, we launch Packalicious, a research initiative aiming to establish transdisciplinary innovation as a collaborative learning ecosystem.

In the initial research phase, a core stakeholder group developed the framework in which Packalicious operates. In the second (current) phase, the developed Packalicious framework is tested and improved. This design iteration builds on a transdisciplinary group-based case study, where real-life packaging challenges are tackled by diverse stakeholders.

In this paper, we define and measure the efficacy of collaborative learning within Packalicious by means of three innovation indicators. The first results indicate that the approach yields more diverse solutions, and a positive connotation with on-the-spot transdisciplinary collaboration. However, it also exposes the differences in discipline-related language and jargon. This paper contributes to academic insights by the establishment of a self-sustaining transdisciplinary learning ecosystem, and the ways in which this bridges gaps between disciplines and stakeholders.

Introduction

Sustainability-related developments become a differentiating factor in industry, legislation, and the public opinion. An area with a strong societal focus on sustainability-related issues is packaging development. Packaging is the object in many sustainability discussions, for its role as a facilitator within a product chain – referring to the primary packaging functions (Ten Klooster 2002, Bramklev 2007, Lutters and Ten Klooster 2008, De Koeijer, Wever et al. 2017), as a spearhead in policies, and for innovations related to material use and waste reductions. Packaging is an inseparable and indispensable part of products. After use of a product, a packaging is superfluous and, in many cases, becomes waste immediately. This creates an incessant flow of materials, resulting in major social dilemmas (plastic soup, microplastics, litter, et cetera). The actual substantiated operationalization of the multifaceted and complex aspects of sustainability in the development of product-packaging combinations is the domain of design and development teams, in which various stakeholders form a multidisciplinary collaboration (De Koeijer, de Lange et al. 2017). However, the complexity and intertwining of different disciplines around packaging leads to complex, system-wide issues that are not easily solved. To tackle this and secure it for future development processes, educating ‘designers of the future’ is essential – this strengthens the connection between education, research, practice, and society.

‘Traditional’ ways of cross-disciplinary collaboration show to be incapable of overcoming these packaging-specific complexities. Although the transfer of knowledge in such an approach appears to be sufficiently successful (Mulder-Nijkamp, De Koeijer et al. 2018, Mulder-Nijkamp, De Koeijer et al. 2019), there is a threat that this knowledge will quickly become obsolete. The operational impact of education currently lags behind the quickly changing developments in industry and legislation to create more sustainable packaging, and requires a more dynamic character.

In current packaging development processes, stakeholders focus too much on solving sustainability issues within their own boundaries. However, the complexities surrounding circular packaging can only be overcome if all stakeholders collaborate (De Koeijer, Wever et al. 2017, Mulder-Nijkamp, De Koeijer et al. 2019). In addition, we claim that both within educational institutions and within companies there is a one-sided focus on the problem, resulting in a lack of a system-wide overview. To do justice to the complexity of this theme, it is necessary for companies, researchers and especially education to blur the boundaries between disciplines and to consider possible solution strategies at the system level (Dorst 2015). The packaging professionals of the future must be able to move across the boundaries of the involved disciplines and be able to frame the problem at a more systematic level, allowing new strategies and solution approaches to emerge. To enable that, the University of Twente launched Packalicious, a research initiative aiming for high-intensity transdisciplinary collaboration, together with the Netherlands Institute for Sustainable Packaging (KIDV) and four Dutch universities of applied sciences. Packalicious sets out to establish a learning community and a platform that build bridges between packaging industry partners, education and research, and governmental stakeholders, in order to overcome the interdisciplinary challenges. We establish transdisciplinary innovation as a collaborative learning ecosystem – stakeholders learn with each other, rather than ‘just’ from each other.

This paper's main contribution is the process of developing and elaborating on an innovative way of empowering transdisciplinary collaboration, where we strive to assemble several theories into a practical approach. Ultimately, we aim to establish a sustainable ecosystem where we share knowledge between different stakeholders and improve the transdisciplinary process by collaboration across borders.

Transdisciplinary Approach

As explained in the introduction, the current dilemmas to develop more sustainable packaging are highly complex and intertwined between disciplines. Following, these cannot be tackled by individual disciplines. In order to solve these ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel and Webber 1973, Marshall 2008), we need to cross boundaries between disciplines and collaborate. Complex problems can only be solved by a transdisciplinary approach (Jantsch 1972), which involves stakeholders within and beyond academia. To better understand this difference, we need to focus on the definition of transdisciplinarity first.

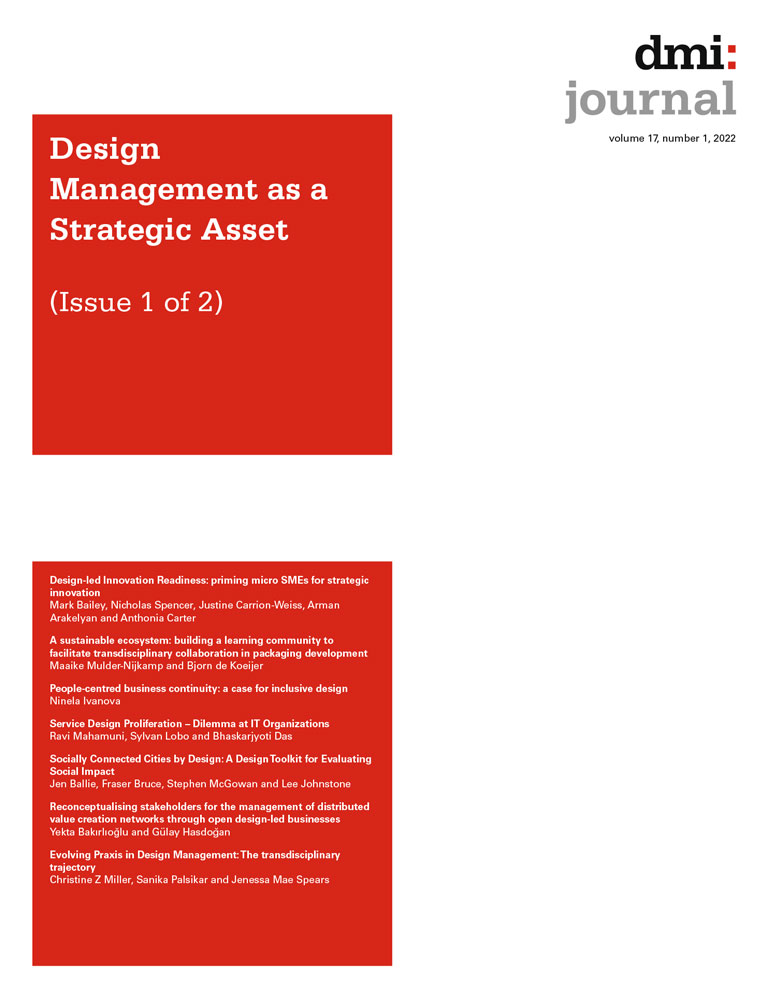

There are multiple definitions of transdisciplinary collaboration, but there is a general consensus that this approach focuses on solving issues in an integrated system (McPhee, Bliemel et al. 2018) instead of aiming to only solve individual issues. Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches aim to achieve a certain goal while combining knowledge of different disciplines and/or collaborating to achieve more integrated results. However, a key difference between transdisciplinary and multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approaches is that transdisciplinarity revolves around emerging knowledge from the integration of disciplinary knowledge into a more systemic approach, to solve complex problems on a societal level (Figure 1). To achieve this, multiple disciplines within and outside of academia must be involved, in a way which accurately reflects a problem's complexity.

Applying a transdisciplinary approach to solve these complex issues produces multiple advantages. Transdisciplinary research has central importance in discussions about new and improved relationships between science and society. Problems ‘transcending disciplines’ can be taken up with transdisciplinary research approaches, which leads to more rigid knowledge interaction between different disciplines (Thompson Klein 2004). By applying a transdisciplinary approach, stakeholders can think across, beyond, and through academic disciplines. This covers all types of knowledge, ideas, issues, or subjects (Ertas, Maxwell et al. 2003).

However, besides al benefits there are also three major challenges that need to be discussed. One of these major challenges is the lack of practical routines or approaches to collaborate together on these complex issues (Wickson and Carew 2014). In addition, the various disciplines do not speak the same language and jargon, and their methods and ways of thinking can differ. Lastly, we face a challenge of integrating different types of knowledge from varying backgrounds within a transdisciplinary design team to reach common goals (Godemann 2008).

In order to set up a successful transdisciplinary approach, we need to carefully investigate and tackle these three challenges to come to better aggregation and a more successful knowledge exchange. The integration of this transdisciplinary approach will be discussed in the next chapter.

Integrating a Transdisciplinary Approach

To better understand the complexity of the problem and its interactions with other related fields, it is important for stakeholders to explore and look beyond each other's expertise boundaries. The definition of these boundaries is based on a system of action which historically grew in order to achieve certain goals with means developed for that purpose. Certain rules apply and tasks are distributed in a specific way (Bakker and Akkerman 2017). This confrontation between boundaries can lead to misunderstanding and choosing the ‘easy way out’. However, these boundaries can also be seen as learning potential and could ultimately lead to an appreciation of each other's points of view, ways of working, and the creation of systemic solutions (Fortuin 2015).

One way to smoothly integrate this boundary-crossing activity is by following Akkerman and Bakker's (2011) four learning mechanisms. They describe four stages: identification, coordination, reflection, and transformation, which will make collaboration and boundary crossing more accessible. The first two stages are based on gaining insights of the expertise per disciplines (who are they, what do they know, what language do they speak?), and the coordination of disciplines (trying to set up a collaboration between disciplines). The last two stages are based on gaining a new perspective on the topic by reflecting (understanding each other's perspective) and transforming (connecting insights to design innovative solutions at the intersection of existing practices). These mechanisms show various ways in which sociocultural differences and resulting discontinuities in action and interaction can come to function as resources for development of intersecting identities and practices (Akkerman and Bakker 2011). Following these steps in transdisciplinary collaboration leads to more focused ways of tackling problems. Nevertheless, integrating these theories into solving system-overarching problems that lead to transformational solutions could be challenging.

Transdisciplinary approaches are a promising notion, but the effectiveness in tackling the world's most urgent problems remains complex (Rigolot 2020). The application of theoretical frameworks in practice is still limited and does not always lead to the desired transformation. Several general design methodologies support stakeholders within transdisciplinary teams to tackle these wicked problems on a systemic level, such as Gigamapping (Sevaldson 2015, Davidova 2017), Reflexive Monitoring (Van Mierlo, Regeer et al. 2010), or the Systemic Design Toolkit (Jones and Kijima 2018, Systemic Design Association 2018). These methodologies enable stakeholders to gain more insights in the complexity and interrelations between disciplines. The challenge particularly lies in the last two phases of Akkerman and Bakker's model, because these require the variety of involved stakeholders to get out of their comfort zone and step into the perspective of another discipline, leading to a transformational change. This method enables a reflection on the important steps to be taken. However, reaching the fourth step of innovation (the transformation level) requires a significant leap. The answer lies in combining systems theory and design reasoning (Dorst 2015, Jones 2015).

Integrating the theories of design thinking (like form and process reasoning), social and generative research methods, and sketching and visualization practices merges the more technical representations of complex social systems with a human-centred approach (Jones 2015). By integrating this collaborative design thinking approach (Dorst 2015), a designer will be able to reframe a complex problem and step into the role of another discipline to solve it.

Dorst (2011) describes ‘design abduction’, which differs from other types of abductive reasoning and shows how different disciplines are dealing with complex problems in a different way. In ‘regular’ abduction (the engineering type of abduction), the outcome of the development and the ways to get there are clear. In the process of design abduction, only the preferred outcome is clear – the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ remain uncertain.

This project focuses on a transdisciplinary approach where synthesis between stakeholders ensures a more solid embedding of academic and non-academic knowledge. This approach differs from ‘traditional’ problem-based learning, where students focus on a real-world problem. We identify a significant variance in required inputs and resulting outputs per stakeholder, when considering development processes. Following, in current processes we can observe the necessity for overarching transdisciplinarity. If multiple stakeholders or disciplines aim to approach problem solving in a transdisciplinary manner, this does not mean the collective approach is a transdisciplinary one. In an ideal situation, everyone contributes to providing input and shares in the final yield. This means that all stakeholders contribute knowledge and can also reap the benefits.

In our journey towards creating a more solid transdisciplinary approach we have learned that every person is unique, and we need to apply everybody's capacity and capabilities to fulfil goals. In order to create a self-sustaining and self-supporting platform we need to create a rich and dynamic learning environment where stakeholders are able to shape networks and share insights, building towards future-proof solutions.

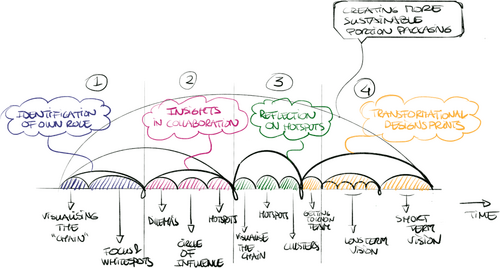

For effective knowledge sharing, it is necessary to understand the overarching system and the influence of one's role in this. Within every expertise there is a certain degree of influence that can be exerted to solve specific societal challenges, the circles of influence (Covey 1989). These circles of influence consist of three layers: (1) the circle of control (where you can directly make a difference), (2) the circle of influence (where you can have an influence if connected to the right stakeholders), and (3) the circle of concern (which covers any element that is within your concern, but to which you do not have direct result-influencing impact). Gaining insight into the ‘circle of influence’ of all stakeholders provides interesting starting points to tackle a problem more concretely. In other words: if we merge the circle of influence of all parties, clusters can be formed where stakeholders can work together to enlarge their influences. By visualizing these clusters, stakeholders can more effectively collaborate on specific themes, which will enlarge their influence and facilitate transdisciplinary learning.

Creating a Sustainable Ecosystem

Packalicious as a self-sustaining platform materializes by means of a continuous iteration of synthesis and analysis steps, following a collaborative design thinking approach. Within Packalicious we strive for a transdisciplinary way of collaborating, in which stakeholders from different disciplines (industry, education, government, research) collaborate on packaging circularity. This new transdisciplinary learning approach can only be achieved by collaborating with all relevant stakeholders, with the creation of this ecosystem as a common aim.

In the initial research phase, a core stakeholder group (including packaging experts, KIDV, lecturers and students representing the involved universities of applied sciences) developed the framework in which Packalicious operates, by means of interactive hybrid brainstorming sessions. In a transdisciplinary approach we set up a vision and co-developed several solution spaces in mixed teams to come up with key elements, requirements, and characteristics for a successful ecosystem. During this process, the methodology of creating learning arches (Windeløv-Lidzélius 2018) was used. These learning arches represent an ‘arc of tension’ around a chosen theme, these are used in experiential learning to create involvement, creativity, and personal commitment. By thinking about the main learning objective and subsequently defining all subgoals, the setup of the learning community was created. In the second phase (the phase we are currently in), the developed Packalicious framework is tested and improved. This design iteration builds on a transdisciplinary group-based case study, where real-life packaging challenges are tackled by a diverse group of stakeholders. With a process of fast-paced design cycles and abductive reasoning steps, the stakeholders develop innovative product-packaging concepts, shaping both solutions for the challenges at hand, and the details of Packalicious as a collaborative learning platform.

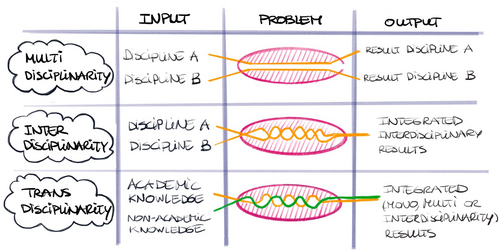

To facilitate transdisciplinary collaboration, we developed a framework combining the four stages as described by Akkerman & Bakker (2011) with the visualization of the learning journey by means of learning arches. In Figure 2, the setup of this journey is visualized; the horizontal axis represents time, with four columns representing the four stages: (1) Identification, (2) Coordination, (3) Reflection, and (4) Transformation.

The visualization contains multiple arches. Per phase, the learning journey is developed, starting at the highest level working towards creating smaller arches. Each arch has three phases: deployment, execution, and landing – so for each learning activity there is a starting phase, the final learnings and the way towards these learnings. When the phase ends there is a ‘moment of celebration’ where all learnings are summarized and deliverables are celebrated. In the figure, this is represented as a curl, visualizing teams being able to reflect on the outcomes and jump into a new learning arch with new knowledge and revived energy. The timeframe of this learning journey is approximately 1,5 days, divided over two sessions: an online session and an onsite session. We divided the learning journey in two larger arches: one representing gaining insight on the topic (phase identification and coordination) and the second arch representing the phases of reflection and transformation by means of creative design sprints in mixed transdisciplinary teams.

Case Study

To validate the efficacy of this transdisciplinary learning ecosystem, we set up a case study in which the focus will be on creating solutions with and within transdisciplinary teams. This case study focuses on creating portion packaging, where we investigated the balance between sustainability and convenience – initiated from a company's real-world dilemma. We translated these questions into more system-oriented topics and extended the team with additional stakeholders who were also dealing with this overarching societal challenge. In this way, we ensured a more transdisciplinary collaboration without only solving a single problem for a single company, ‘just’ with a lot of stakeholders.

In this paragraph, we define and measure the outcomes of the case study, and with that: the efficacy of collaborative learning within Packalicious. We address three innovation indicators: (1) transdisciplinary collaboration as a process, (2) variety of solution spaces, and (3) stakeholders' responses. In the next part the setup of the case study is explained, followed by the three innovation indicators.

Case study setup

The case study consisted of two sessions: a two-hour online session and a full-day onsite session. In the online session we invited stakeholders from the overall packaging chain: the case owner (Van Oordt The Portion Company), a material supplier (Sappi), a recycler (Milgro), and a client (Peeze Coffee) that are all involved in solving this challenge. Besides that, we involved governmental stakeholders, and researchers with a background in consumers' disposal behaviour and sustainable packaging development. The focus of this session was to gain a better understanding of the complexity of the problem and to investigate the focus and white spots of all participants, finally resulting in an overview of the circles of influence (Covey 1989) and the key development clusters (‘white spots’), visualised in Figure 3 (simplified).

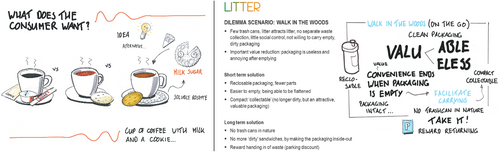

The second session was scheduled in a live setting, aiming for the creation of additional insights into the white spots, and the investigation of the solution space with mixed teams. To scale up the transdisciplinary approach we invited additional (peripheral) stakeholders: the four universities of applied sciences (students and lecturers/researchers), NGOs (Nederland Schoon), and manufacturers and brand owners dealing with the same portion packaging dilemma (Kraft Heinz and Smurfit Kappa). We split this second session into two parts. In the first part we focused on discussing the outcomes of the online session (reflection) and adding each stakeholder's own insights, resulting in a circles of influence overview representing all parties (Figure 3). Each stakeholder was requested to position their post-it notes of the previous round (in which we thought about individual white spots and dilemmas) on the circles of influence overview. In a second step, key development clusters were formulated based on this collection of post-it notes. The overview of the circles of influence and key development clusters facilitated the connection between stakeholders and resulted in a better understanding of the topic. The second half of the onsite session was focused on creative design sprints in five teams of mixed disciplines, in which participants were requested to come to diverse types of solutions: a moon-shot (creating an ideal, no boundaries, off-the-charts proposal) and a short-term solution (practically implementable within two years). All teams were formed as a mix of disciplines, with the students as discussion leaders. To guide teams in their creative process, posters and card sets targeting ‘rethinking’ as a means of creative reasoning were available. This poster, the assignment approach and the setting of the creative design sprints are represented in Figure 4.

Transdisciplinary process

The first results indicate a positive connotation with on-the-spot transdisciplinary collaboration. All stakeholders indicated that they had never worked with such a diverse group before. Especially the stakeholders who would probably not directly interact with each other (e.g., governmental stakeholders and industry representatives) indicated the advantages of discussing these challenges together. However, this approach also exposes the differences in discipline-related language and jargon, which emerges more evidently in such a community where every stakeholder acts as a ‘learner.’ Stakeholders were clearly describing the difficulties in understanding each other's ‘language’, but even more importantly emphasized the differences in the approach to tackle these complex problems. The design-thinking approach as it is applied in this case showed to be quite challenging for stakeholders who are used to discuss and solve problems on a more abstract level (e.g., governmental stakeholders). In this case, the students fulfilled a critical role, because of their position as a ‘translator’ between disciplines. By asking the right questions they were able to enable stakeholders to understand and use the approach to its full potential.

We also saw a major difference in generational attitude between the students and the other stakeholders, regarding the topic of sustainability. The younger generation repeatedly questioned why certain choices were made in which they condemned the chosen strategy without expressing so literally. This resulted in a more defensive position of other stakeholders. The younger generation was building towards creating daring solutions and were more open towards different perspectives, while the company representatives and other stakeholders tended more towards solving the issues within current boundaries. They were more concerned about the feasibility of the results. We observed this generational tension to act as a trigger for all stakeholders to reach for the best results.

This shows the importance of involving a diverse set of generations in these transdisciplinary sessions to create solutions that are future-proof without neglecting the feasibility. Besides that, the presence of different disciplines stimulated each stakeholder to involve different perspectives into their thought process, and to see where connections can be made to solve a societal challenge.

Variety of solution spaces

The initial results indicate that the approach yields more diverse solutions. Based on the formulated clusters, the five mixed teams presented five completely different solutions. Some of them were oriented on a more concrete solution (see Figure 5, left). This solution was based on thinking about consumer needs (having a fresh cup of coffee without useless packaging), resulting in a solution with a soluble rosette containing milk and sugar. Other groups tackled the challenge by means of a more systemic approach (Figure 5, right), where they also thought about involving legislation and the overall problem context.

We noticed that all teams collaborated differently. Some of them focused more on building on their own experiences by giving practical examples. Other groups were creating a simple scenario to make it easier to understand each other and to make the solutions more specific and realistic. Overall, we experienced the students being helpful in getting the teams in the creative mode, using the abductive design thinking method. Besides the different approaches of the groups, we also noticed that group dynamics played a significant role. Halfway through the session, we decided to exchange the students with another group, and this really helped in providing fresh energy. This also shows the importance of interacting with other disciplines and training young designers to cross ‘borders’ between disciplines.

Stakeholder responses

Via an online post-session survey we evaluated the participants' views on and their experience of the live session based, on four questions: (1) “What was your experience of the first live Packalicious session?”, (2) “Has working in design sprints with different disciplines helped to create new insights/scenarios around the ‘sustainability’ of portion packs?”, (3) “How did you perceive the collaboration between the different disciplines in the design sprints?”, and (4) “How can we improve the next session?”. We received nineteen anonymous responses out of twenty-four participants. Based on the results we can conclude that it was a successful event, since participants were incredibly positive about the ambiance, the truly diverse group of stakeholders, and the ‘energy’ of the session. One of the participants experienced “Good atmosphere, a lot of dynamism, and looking at the process and the result from many different angles.”

However, there are also some aspects that needs to be improved with regard to gaining insights into the problem. Inviting more stakeholders for the onsite sessions resulted in a less clear overview of the themes and the actual core problem. The ‘new’ stakeholders (added to the participant group after the online session) missed the rich online discussions. One participant mentioned that the focus could be strengthened: “There was a particularly good atmosphere, everyone was eager to contribute with each other. Things that could be improved relate to focus. The first session had apparently yielded quite a lot of results, but we did not follow this up very concretely. The ‘problem’ was therefore different for everyone”. Another participant mentioned the lack of a clear follow-up as an aspect to improve in the future: “Good mix of universities, business, government, et cetera. What could be better is the follow-up and a clear overview of the next steps. In addition, my company wants to know what we can expect from this workstream at what time. I cannot answer this right now.” Regarding collaboration, we can conclude that bringing al these disciplines together does not automatically lead to knowledge exchange.

The difference in language between disciplines and the more abstract theme of this group resulted in a less focused discussion. Some of the participants mentioned the relevance of the case owner to assess the more creative ideas: “It is always good to put different disciplines together and especially the case owner himself, who knows everything about the product and the philosophy behind it. They can provide the framework you want when you have ideas and want to assess them, for example, on how realistic they are. We can also help the client to make things concrete that they secretly know, though have not yet made very clear. The client was also questioned a lot to find out the ‘why’ behind everything”.

In general, we can establish that the first results indicate a positive response. In the session, we experienced rich interaction between different stakeholders, struggling with the same issues. By discussing these dilemmas together with the younger generations, industry stakeholders were able to explore new areas without immediately eliminating ideas because these would not ‘fit in their current industry’. Most importantly, we also observed the interaction between stakeholders after the session. This networking can be seen as an equally valuable transdisciplinary interaction in comparison to the direct outcomes of the session.

Evaluation and Conclusion

The first case study, as described in this paper, shows a successful collaboration between different stakeholders and proves the necessity of solving these challenges by visualizing each stakeholder's scope-related white spots and restrictions to collaborate and co-design.

By offering a framework where participants are compelled to explore and cross the boundaries by following different phases in the transdisciplinary collaboration, our approach leads to merging different disciplines' established procedures. In the first two stages, identification and coordination were addressed by using the work of Covey (1989). This resulted in a clear overview of the possible interactions between stakeholders to enlarge and strengthen everyone's circle of influence. In the second part, the focus was more on reflection and transformation. Looking at the results of the onsite session we could not claim that all groups reached the transformational level yet. However, we do see that these first results are promising and do consider multiple perspectives, resulting in a more diverse outcome. We do need to emphasize that the results are still on an abstract level. In order to achieve the determined goal, it is necessary to translate these ideas into more concrete solutions. However, we can establish that this approach yields the first steps in the process towards more sustainable solutions. Besides that, rich interactions between different stakeholders have been established, which do make a difference in solving these complex societal issues more easily.

Future

Based on the positive evaluation of all stakeholders, we find that we need to continue developing this platform to facilitate transdisciplinary learning, both within and beyond packaging development. However, we do need to perform more research about the way stakeholders exchange knowledge to improve the communication between different disciplines. One of the aspects that plays a role in this process is the group dynamics, which is currently under-addressed.

Besides that, we also need to improve the development of education to students, the packaging specialists of the future. Besides having technical knowledge about specific production techniques and materials, they also need to be prepared to talk to different disciplines. By embedding more transdisciplinary projects in their curriculum and by paying attention to boundary-crossing skills, these students will be capable of solving these complex societal issues.

The establishment of a transdisciplinary learning ecosystem is not only relevant in the field of packaging sustainability. In a multitude of fields, we face societal issues that become increasingly dynamic, complex, and intertwined. Defining stakeholders as ‘learners’ and shaping transdisciplinary collaboration and innovation is key. With Packalicious, we develop a blueprint for these developments which can be translated to other fields as well. With this research, we set out on the journey to further establish transdisciplinary learning ecosystems.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation and gratitude to all participants who empowered the organization of the sessions: KIDV, the involved lecturers and students of the four universities of applied sciences (HAS, HHS, HvA, NHL Stenden), industry partners (Van Oordt The Portion Company, Kraft Heinz, Sappi, Smurfit Kappa, Milgro), government/NGO's (Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, Nederland Schoon), and researchers (University of Groningen, Utrecht University).

Biographies

Maaike Mulder-Nijkamp, is a senior lecturer and researcher from the University of Twente. Maaike was involved in a research project about transdisciplinary collaboration in the field of sustainable packaging for which she received a Comenius Senior Fellowship award in 2020. In this project she co-created the learning community Packalicious, which brings education, academia, the public and private sectors together to come up with transdisciplinary solutions in the field of sustainable packaging. She also runs the special interest group transdisciplinary collaboration for the Comenius network.