Using a Codesign Workshop to Make an Impact with Codesign Research

Abstract

Professional services companies are relaxing the tone of voice and personality they use to interact with clients. In response to these trends, we used codesign methods to explore how clients want to interact with our company. Study findings revealed several opportunities for creating stronger connections with our clients. To increase the impact of our research, we conducted a codesign workshop with stakeholders across the company to share insights and co-create opportunities in an interactive format. This workshop created buy-in for some controversial findings and led to the creation of a task force focused on integrating study findings into multiple marketing and design projects. This paper summarizes the study findings and describes the codesign methods used in the internal stakeholder workshop. We will also describe workshop outcomes and discuss the benefits of using codesign to share study findings.

Introduction

Professional services companies are relaxing the tone of voice and personality they use to interact with clients. For example, BambooHR uses bright colors and endearing panda cartoons throughout their website (BambooHR®, N.d.), State Farm uses a humorous commercial, which features a customer who calls “Jake from State Farm” (Spier, 2019), and Allstate uses a humorous character named Mayhem in commercials. “Mayhem represents all of the freak accidents or situations that you could never envision actually happening, but with the reassurance that even under these circumstances, Allstate has you covered” (Spier, 2019). The Mayhem and Jake characters from State Farm and Allstate are interesting departures from the companies’ previous approaches (Mhlanga, 2017). Before Mayhem, Allstate chose a well-respected actor, Dennis Haysbert, to leverage his authority to communicate that Allstate provided protection for customers (Speier, 2019), and State Farm’s previous marketing message emphasized that customers could rely on the company by using the tag line “like a good neighbor, State Farm is there.” (Spier 2019).

The increased use of humor and less formal interactions with customers may seem counterintuitive at first glance for companies that provide serious services related to topics like finances, insurance, or business processes. In their podcast exploring whether humor is appropriate for a business website, Perry and Dorn (2016) say that it is not appropriate to use humor for some types of companies. “You will not see the SPCA [Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals] …website using lots of humor in their marketing material because their subject matter is very serious” (Perry and Dorn, 2016). This stance, that humor and lightheartedness are not appropriate for delivering serious services, is a foundational stance for our company, which provides services that support critical business processes. Our company’s brand, like Allstate’s and State Farm’s, is based on a long history of providing accurate, reliable information, and serving as a trusted, knowledgeable advisor. However, we noticed that many professional service providers like State Farm and Allstate have shifted to more lighthearted interactions with customers, using humor and bright colors in their websites and messaging. Based on these trends, we conducted a study to find out what our customers wanted to experience when interacting with our company. Findings indicated that while they resonated with some elements of our brand like accuracy and trustworthiness, clients also wanted to see brighter colors and more lighthearted messaging in our online platforms.

We decided to share our findings through an internal, multi-disciplinary codesign workshop, rather than through the typical PowerPoint presentation format, in hopes that the research might make a stronger impact within the company. The workshop included 45 participants from 8 business groups across the company and lasted a full day. Workshop participants focused on two main activities. First, they collaborated with a multi-disciplinary team composed of members from several business groups to create new ideas for making stronger connections with customers. After presenting these ideas to the larger group, participants then rearranged into single-discipline teams to collaborate with colleagues in their respective business groups. These business group teams created and performed a skit demonstrating how their department should interact with clients, based on study findings. The workshop codesign methods allowed internal business groups to interact with the findings and collaboratively determine how to incorporate clients’ requests into their daily work. The workshop made a bigger impact in the company by allowing participants to actively experience the data, instead of passively listening to a PowerPoint presentation (Sanders and Stappers, 2008). We will describe the workshop methods and outcomes and discuss the benefits of using codesign to share study findings, based on survey feedback from workshop participants.

Brief study overview

Before we describe the details of the workshop, we will describe the background context by providing a brief overview of the study that informed the workshop. To get a better understanding of our clients’ needs and aspirations when interacting with our company, we conducted this study to explore client expectations for our company’s tone of voice, style, and personality. We wanted to understand what tone of voice and wording we should use in our software application, company website and marketing materials, what kinds of graphics, colors and images clients resonate with most, and what kinds of behavioral characteristics they expect when interacting with our company.

Brief summary of study methods

We recruited 23 participants who matched characteristics that are typical of our clients, sampling across a range of business sizes, industries, ages, genders, and job titles. Each participant began the study by completing a seven-day workbook, which asked them to track the software and phone applications they interacted with and to write down how they felt about these apps. After seven days, we conducted a 30-minute, one-on-one remote interview to review each participant’s workbook. When the interviews were finished, participants came to our company’s location to participate in one of four group sessions. Since we wanted to see if there were any differences in expectations between smaller and larger companies, two of the groups had participants from smaller companies, and two had participants from larger companies. Each group had 4-7 participants. During the group sessions, participants completed three activities: a collage, a participatory design session, and a design evaluation.

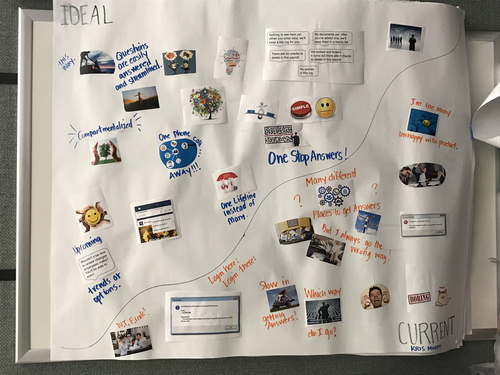

Collage: current vs ideal system

Each group session began with a brief overview and introductions. Participants then created a collage using images and words from a pre-printed packet provided by the researchers (Figure 1). The collages compared their current system with their ideal system. The systems they were asked to compare were similar to the B2B software that our company provides. After completing the collage, participants presented it to the group and explained what the images meant to them.

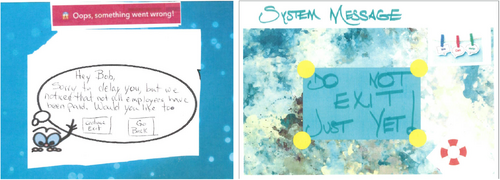

Participatory design for four scenarios

After presenting their collage, participants created a different ideal design for each of four scenarios: an error message, a help message, a chat interaction, and a new product announcement. Examples of two participant designs for error messages can be seen in Figure 2. To create their designs, participants chose from a wide range of pre-printed colored backgrounds, images, and message boxes. They glued the images and message box onto their chosen background and hand-wrote a message in the message box. When they finished their designs, they presented them to the group and explained what their messages and images meant to them.

Design evaluation

The last activity of the workshop was a design evaluation. Participants examined and rated design concepts in a pre-printed booklet and responded to questions about those designs. After completing the evaluation on their own, participants then participated in a facilitated discussion about the designs.

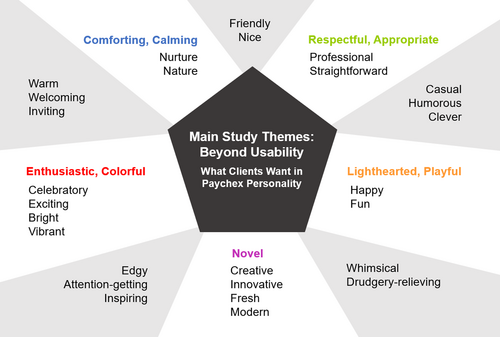

Brief summary of study findings

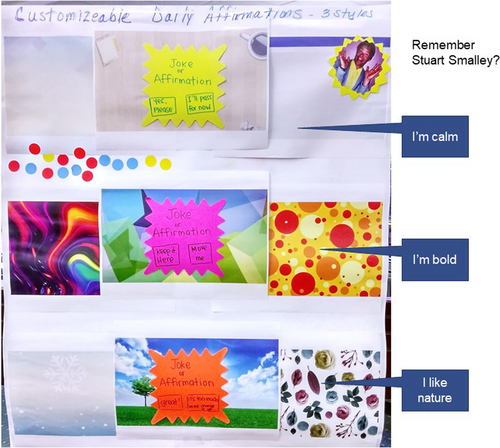

Study participants were very enthusiastic when telling us what they want to experience when interacting with our company. Many of them work with our software and services daily, and they placed high value on having a friendly, casual relationship with our company. Rather than seeing our company as an elevated source of knowledge and information, they wanted to be treated like a partner. They expected our system to tailor interactions to the situations they were experiencing. If they were in the help section, they wanted calming colors and images to help relieve their stress, and if they were viewing a new product announcement, they wanted colorful, celebratory images and wording to attract their attention, and encourage excitement about the new product. They also craved novelty and lightness in the course of their daily work, generally preferring bright colors and humorous images, and rejecting more serious, formal, and boring images. The diagram in Figure 3 provides a summary of the main themes that participants valued for interactions with our company.

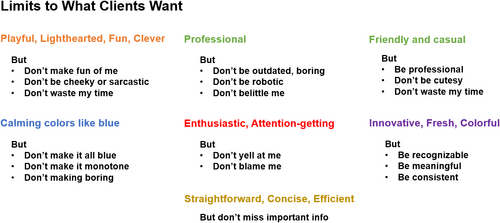

While humor, friendliness and bright colors were highly valued, participants did mention that there should be some limits to how these were implemented, as summarized in Figure 4.

How we used a codesign workshop to share findings with internal stakeholders

Our company has a strong brand and a long history of presenting ourselves as a professional, reliable source of information for our clients. We expected that the strong desire of study participants to experience more casual, colorful, lighthearted interactions with our company would be new, and possibly surprising to some groups within our company. These findings were relevant to many individuals from various groups distributed throughout the company, many of whom did not interact directly with each other on a regular basis, and many of whom did not work in the same building. This combination of factors meant that a typical PowerPoint presentation to share the findings would not be enough to make much impact within the company.

To increase the impact of our codesign research, we conducted a codesign workshop that included stakeholders from several business groups across the company. As Roberts, Petrelli, Ciolfi, & Avram (2019) found, codesign provides opportunities for interdisciplinary teams to create mutual understandings and to negotiate shared goals. In accordance with the Drain and Sanders (2019) Collaborative System Model, we constructed interactive, collaborative codesign methods to provide the opportunity for the disparate groups in our company to actively experience the findings, and to co-create new ways of interacting with clients. As Pirinen (2016) discusses, co-design is a powerful tool for bringing multi-disciplinary networks of stakeholders together in order to “create and visualise new viable solution ideas.” Stakeholders in our workshop participated in a series of two different team activities which allowed them to interact with and embody study findings, and to co-create solutions that would help build stronger connections with our clients (Sanders and Stappers, 2008). We will next describe the codesign methods, and then present a summary of workshop results and outcomes.

Workshop methods

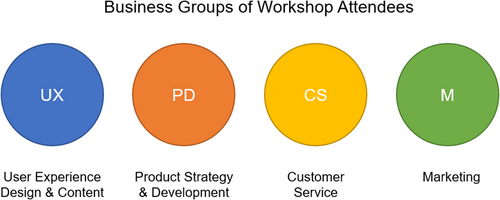

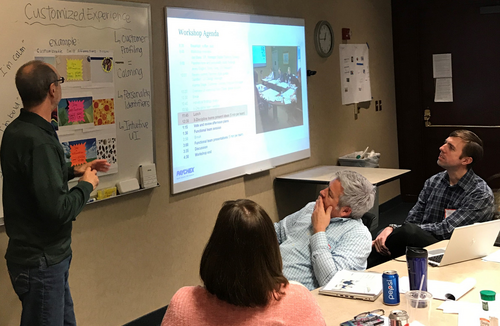

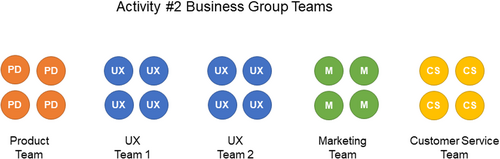

We conducted a full-day workshop that included approximately 45 attendees from user experience (UX) design, user experience (UX) content, product strategy and development, customer service, and marketing, as seen in Figure 5. The workshop began with a quiz and three presentations and ended with two team-based activities. When constructing the workshop plans, we considered many of the elements laid out in the Collaborative Systems Model (Drain and Sanders, 2019). We were careful to adapt the information presented, design environment, and design activities to the backgrounds and knowledge of the participants. The workshop took place in a large conference room that was accessible to all participants, allowed participants to easily transition from one team to the next, and provided enough space for teams to display their concepts and ideas. We tailored the presentation of research findings to emphasize the details that were most relevant to those attending the workshop, and we invited participants from other groups to present their own perspectives on the topics being discussed. We also constructed a sequence of activities that allowed participants to build trust and rapport with other workshop participants in order to feel comfortable participating in the skits at the end of the session. The next sections describe this sequence of activities.

Quiz and presentations

We began the workshop with a quiz that focused on what clients want when interacting with our company. The quiz was composed of true/false and multiple-choice questions about client preferences, based on study findings. For example, multiple choice questions asked quiz-takers to guess the top background chosen by study participants for their scenario designs, and to guess the most popular images representing participants’ ideal system designs. True/false questions required quiz-takers to determine whether quotes and facts from the study were real or made-up. Participants completed the quiz on their own before the presentation, and then scored their answers as the findings were presented.

The purpose of the quiz was to build curiosity about the codesign research, encourage active listening during the presentation, and help participants become aware of any pre-existing assumptions they had about client aspirations. After the presentation, we reviewed the answers to the quiz and discussed the findings that were most surprising to attendees. This discussion helped reveal hidden assumptions about clients, which were not supported by study findings. For example, many workshop attendees were surprised by the whimsical images that were frequently chosen to represent clients’ ideal systems, as shown in figure 15. They assumed that clients would expect more serious, professional interactions with our company, since we offer services to help them with critical business processes.

In addition to the quiz and presentation of study findings, we also invited the marketing group to present current style guidelines for the company brand, and the user experience (UX) content group presented how they applied the brand guidelines to the messaging they were creating in our products. This allowed attendees to discuss what the brand was already doing to meet client aspirations, and to think about opportunities for building even stronger connections with clients.

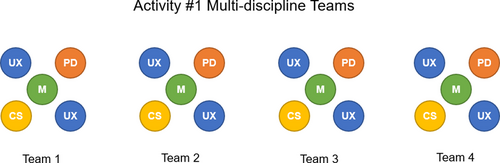

Multi-disciplinary concept-generation

After workshop attendees discussed and absorbed the study findings, they divided into pre-assigned multi-disciplinary teams (Figure 6). Each team included at least one person from user experience (UX) design, user experience (UX) content, product strategy and development, customer service, and marketing. Teams were given an hour to create new ideas and concepts for how our company could establish stronger connections with clients. We gave them large sheets of paper and asked them to create sketches and concept summaries that could be presented at the end of their session. We designed this first group activity to be multi-disciplinary to increase the range of ideas that might be considered (Watts-Perotti and Woods, 2009). The multi-disciplinary nature of this activity also allowed workshop participants to share ideas on equal grounds and develop rapport with one another and become comfortable enough to participate in the skits at the end of the session (Drain and Sanders, 2019; Pirinen, 2016).

For this first activity, each team was assigned a different theme that was relevant to the study findings. For example, one team created concepts showing how our company could be more comforting (Figures 8 and 9). Another team examined how our company could be more creative, innovative and fresh (Figure 7). Other themes included how our company could be more light-hearted, colorful, adaptive, novel, and smart. These terms came directly from the codesign research findings. All of the themes were all highly valued by study participants when describing what they wanted to experience when interacting with our company. At the end of the hour, each multi-disciplinary team presented a five-minute summary of the concepts and ideas they generated for their theme.

Voting

The teams attached their concept summaries to the wall when they finished their presentations. After all teams presented their ideas, each person placed circle stickers next to their favorite ideas, as shown in Figure 9. This exercise allowed participants to individually process the presentations and form a personal stance about how our company could strengthen connections with customers.

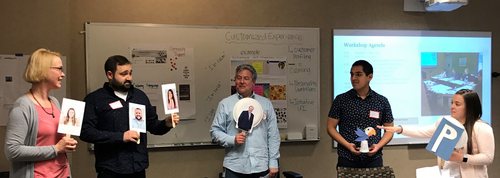

Business group team skits

For the afternoon session, workshop participants divided into single-discipline business group teams (see Figure 10). The goal for each group was to create and present a skit showing how our company should interact with clients. We asked teams to create one or more characters to represent our company, using a wide range of craft materials, hot glue, and recycled objects (Figure 11). We chose the skit for the last activity because this format would allow workshop participants to integrate and embody study findings and could serve as an analogy for how our company might interact with clients. The purpose of the workshop was to determine how our company could create stronger connections with our clients and the skit allowed teams to explore this goal in an interactional format.

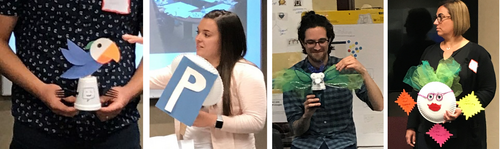

After creating one or more characters to represent our company, teams wrote a skit to demonstrate how those characters should interact with clients in three different scenarios of their choice. We provided a set of ‘puppets’ to represent clients in the skits. Each puppet exhibited a different expression of emotion including frustration, boredom, anxiety, happiness and contentment. The teams then performed the skits, using the character they designed to represent our company, together with their choice of emotion puppets to represent one or more clients (Figures 12-14).

Workshop results

The workshop was considered to be very successful by the company. The morning session generated 25 concepts showing how our company could strengthen connection with clients, and the afternoon session generated approximately 30 insights and new ideas for how our company could better meet our clients’ underlying needs and expectations.

What workshop participants found most interesting and surprising

When we finished presenting our findings in the beginning of the workshop, we asked workshop participants to write down 3-4 things they found most interesting or surprising. Analyses of the responses revealed 55 different facts that they were interested in or surprised by. For example, they were surprised that all age groups wanted more color and fun, even in the professional services software that we sell. They were also surprised that study participants wanted our company to be a supportive partner, rather than the confident authority and source of information that we have been portraying in our corporate image, and they were especially surprised to find that some of the error messages in our software made study participants feel like they were being yelled at, or talked down to. For example, study participants commented that words like “credentials” in error messages were too formal and unfriendly. Workshop participants also found it interesting that study participants expected the system to anticipate their needs, adapt to their experiences, and provide choices for how clients can interact with our company.

Workshop participants were also surprised by the images chosen to represent study participants’ ideal systems. Study participants did not choose images of traditional suit-wearing business professionals. The few images that did contain people wearing suits portrayed them being whimsical, as seen in the examples shown in Figure 15.

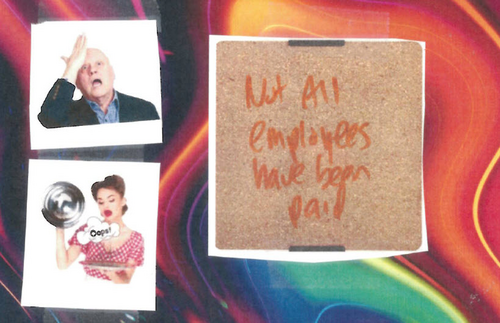

Workshop participants also found it interesting that study participants wanted our company to provide them some relief from the drudgery of their everyday work, as shown in the error message created by one of the study participants in Figure 16. The error message, “not all employees have been paid,” is a serious error, and is shown if a user tries to exit the system before all employees have been paid. However, the study participant who designed this error message included some whimsy in his design, shown in the groovy background, together with the man hitting his head in surprise, and the woman serving an empty platter, with the thought bubble saying “Oops.” When explaining this design, the study participant commented that he wanted to see something that would make him laugh throughout the day. He said that many of the traditional error messages made him feel like the system knew more than he did and made him feel like the system was laughing at him. This supports findings by Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice (2007) who found that humor is a factor in counteracting mental depletion.

Increasing the impact: how workshop participants incorporated study findings into their concepts and skits

While the concepts generated by the morning multi-disciplinary teams were intentionally created to address a specific study finding theme, it is interesting to note that the afternoon single-discipline business group teams also incorporated study findings into their skits, even though they were not required to do so.

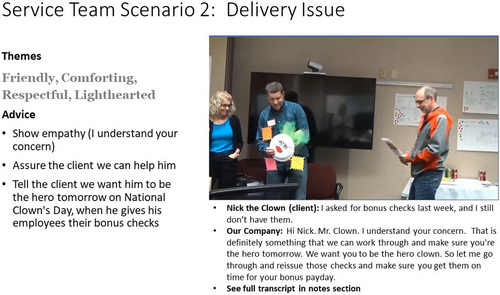

To analyze the afternoon business group team activity, we reviewed video recordings of the skits and noted the themes that were incorporated into each scenario. We also summarized the advice that the teams provided for how our company should interact with clients in each scenario (see Figure 17). This analysis helped our team understand which themes resonated most with workshop participants. We also distributed our summary to the workshop participants, so they could refer to the workshop results in the course of their daily work.

A total of 17 themes were incorporated into the full set of scenarios. Every scenario was unique and relevant to the daily work of the business group team who created it. The themes that were most frequently used were friendly (used in 9 of 12 scenarios), adaptive (used in 6 scenarios), smart (5 scenarios) and light-hearted (4 scenarios). In addition to incorporating the themes into the narrative of their skits, workshop participants also incorporated the themes into the characters they created to represent our company. For example, one team portrayed our company’s customer service department as a superhero. That team also created a colorful parrot to represent the company. Another team created a colorful, whimsical phoenix, and a third team created a colorful customer service person, as shown in Figure 18. The images of these characters were consistent with the images that participants used in their collages. They were quirky and light-hearted, and none of them wore serious business attire.

The results from the afternoon business group team activity indicate support and buy-in for study findings, since workshop participants were willing to incorporate study findings into scenarios that were relevant to their specific group. By increasing buy-in and allowing workshop participants to explore how study findings were relevant to their work, we increased the likelihood that they would incorporate study findings into their daily work, thus increasing the practical impact of the study within the company.

Feedback from workshop participants

At the end of the workshop, we distributed a survey to gather feedback from participants. Sixteen workshop attendees completed the survey. We asked the following open-ended questions: Was the workshop valuable? What did you like about the workshop, and what could be improved? All respondents indicated that they found the workshop to be valuable. Nine liked that they gained valuable insights and appreciated the opportunity to collaborate and network with people outside their discipline. Four respondents liked the interactivity of the exercises and appreciated gaining new knowledge about client needs. Those who offered improvements commented that the workshop should take less time and requested a “takeaway” slide summarizing condensed findings and next steps. Others said they would like to participate in this kind of workshop more frequently.

Discussion and conclusions

The workshop results discussed above are certainly substantial. A single, day-long workshop generated a total of 55 new concepts and ideas for how our company could strengthen connections with our clients. However, we believe the most important benefit of the workshop was the way in which workshop participants were exposed to study findings. In the beginning of the workshop, participants were given the opportunity to discuss study findings with people outside their business group. The findings were relevant to all attendees, but different findings resonated with different business groups, and members of each group interpreted the findings in different ways. Mixing the groups for the first activity helped people understand how their work connected with other groups within the company. It also helped them understand the various interpretations and perspectives of people who did similar work, or who shared responsibilities with them. As described in the workshop survey findings, many participants found this multi-disciplinary activity to be very beneficial to their work.

Another important workshop result is that workshop attendees were required to interact with study findings, create a stance toward the findings, and embody the findings in the concepts they generated and the skit they performed (Sanders and Stappers, 2008). The interactive aspect of the workshop made it more likely that participants would remember the findings than if they listened passively to a presentation. In addition to creating new concepts and ideas in reaction to study findings, participants also voted on their favorite ideas. This exercise gave them the chance to form a stance about which findings were interesting and relevant to their work. The afternoon exercise then allowed participants to synthesize the findings in the context of their specific business group. The skits they created addressed three scenarios of their own choosing. By collaborating with other members of their own work group and creating scenarios that were relevant to them, this last activity allowed workshop participants to get a deeper understanding of how the study findings were relevant to their daily work.

While it is impossible to trace exactly how study findings were integrated into the daily work of all workshop participants, several outcomes indicated that they were still processing and using the study findings, even months after the workshop. For example, the UX content team has integrated some of the study findings into their style guide, and we have observed that some of the images and messages in our company’s software have become lighter and more casual.

Another major outcome of the workshop was the establishment of a “Tone of Voice Task Force,” which had the goal of aligning multiple groups across the company, in order to create consistent content that would resonate with our clients. This task force met regularly and invited us to participate in some workshops that were used to kick off the redesign of the company’s website. Both the UX content team and the new task force could be defined as design collectives which carried the design concepts from the workshop forward and kept the research findings alive, as discussed in Dubois, Le Masson, Weil, & Cohendet (2014). Not only did the workshop produce new concepts and ideas, but it also contributed to new relationships embodied by the task force, thus facilitating change within the organization and supporting innovation (Dubois et al., 2014)

The codesign methods that we constructed for the workshop were conducted as a carefully planned series of interactive activities that helped workshop participants embody the findings, develop rapport with members of other business groups, and determine how workshop findings were directly relevant to the work of their specific business group. The initial multi-disciplinary group activity allowed participants to understand how their work connected to other business groups. The voting activity helped them create a stance toward the research findings, and the final group session allowed them to determine implications for their specific business group. This carefully planned sequence of interactive activities has allowed our study to make a significant impact within our company. As participants mentioned in the feedback survey, the workshop fostered new relationships within the company and even contributed to a new task force which implemented some of the findings. Using codesign methods to share our codesign research findings increased the impact of the research by allowing stakeholders to deeply process the findings in the context of their own business group, therefore increasing the likelihood that the findings will live on in their day to day work.

Biographies

Jennifer Watts-Englert is a senior User Experience Researcher at Paychex and an Adjunct Professor for RITX and the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering at the Rochester Institute of Technology. She has co-authored 22 patents and has led research and design projects focusing on human capital management (HCM), call center and customer service operations, business processes, consumer and professional photography, professional work practices, analytics, digital privacy, healthcare, innovation, and the future of work.

Emily Yang is a User Experience Researcher at Paychex. She received a Master's of Science in Human Technology Interaction. She has worked on various technology projects that focus psychology and people.