Idea Facilitation—A Tool for Experience and Service Innovation

Abstract

Product and service innovation does not happen in isolation; it requires a cross-functional team—most of whom are not designers and may not even be familiar with design practices. In digital product or service offering, more often than not the core team developing/enhancing product consists of multiple functions—from design and engineering to marketing and sales, with little or no familiarity with design processes and practices such as creative ideation. In such cases, ideation becomes a platform for groupthink and corporate inertia, deterring lateral thinking and innovation.

Hence, a structured approach to idea facilitation can help achieve the maximum opportunities availed by ideation sessions: innovative experience and service ideas. Structured ideation frameworks can discourage linear thinking and encourage teams to think strategically and laterally—by switching perspectives, identifying multiple points of view, challenging assumptions, and contextualizing problems.

This paper provides a number of idea facilitation frameworks that enable creative and innovative outcomes when working with a multifunctional team—with design and nondesign professionals with various levels of product–service development experience. These frameworks bridge the gap between insights and strategy and create conditions necessary for creative and lateral thinking. Additionally, it provides best practices to help operationalize idea management.

1 Introduction

Ideas not only help us understand the world; they fuel new directions. Ideas are in fact one of the most powerful forces shaping the human culture, powering industries and businesses and bringing about product–service innovation. Thus, ideation—the creative process of generating original ideas—is essential to innovation. Ideation is a means of both solving problems and identifying opportunities. In this context, new ideas mean thinking beyond the typical solutions, or beyond the organizational dominant knowledge—finding different angles and alternatives.

In designing an experience and service, the main aim of ideation is to use creativity in order to develop solutions. It is one of the basic skills taught in every design school and is an internalized process for every trained designer. The concept of ideation is embedded in design education and practice as a series of “reflections in action” that structure and explore a problem as a means to creating a solution, manipulating tacit and explicit knowledge (Schön, 1983), which means broadening the problem–opportunity and considering a variety of solutions. This consideration of seeing a problem in various ways is essential to the act of designing and is the very core of ideation.

From early sketches and storyboards to other methods of visualization, almost every design specialization uses some form of visual ideation to (1) form ideas, (2) articulate them, and (3) refine ideas into concepts. In Innovation, Design Engineering Organization’s design thinking process, ideation is deemed as a second phase, after empathizing. It is a fundamental and foundational part of creating new products and services. However, thinking unconventionally or beyond the current situation is not a skill possessed by every discipline.

1.1 Ideation in cross-functional teams

In the context of product and service, innovation does not happen in isolation, nor does development of a product or service. It requires a cross-functional team—most of whom are not designers and may not even be familiar with design practices such as creative ideation. In digital product or service offering, more often than not the core team developing/enhancing product consists of multiple functions—most of which are not product creators or makers, such as business, marketing, and sales, with little or no familiarity with creating new, let alone design, processes and practices such as ideation.

Instead, in cross-functional settings, ideation has become synonymous with group thinking, cognitive inertia, and adherence to the status quo. The unstructured groups, left to their own devices, are not effective in developing creative ideas (Brown and Paulus, 2002). This is similar to what brainstorm became before the prevalence of the term ideation in corporate America—a roundtable meeting that often gives way to fear of judgment, cognitive inertia, and a lack of innovative or out-of-the-box thinking (Isaksen and Gaulin, 2005). Essentially, such ideation sessions fail to bring out the value of a group with its breadth of knowledge and various viewpoints.

Additionally, it is difficult for most individuals to think beyond their expertise, especially if the cross-functional team has deep, technical expertise in their field and function. Although that deep expertise is extremely valuable in the various stages of experience and service development, it inhibits broad, lateral thinking.

1.2 Gap between insights and innovation strategy

Today, with companies doubling down on accumulating qualitative and quantitative research on product, customers, and competition, there is no dearth of data. Yet, we have witnessed many times how the most amazing research can lead to the most unamazing and underwhelming products. Why does this occur? Is it an organizational problem, or a problem with the field of practice-based research (i.e., short-term research for the purpose of developing products and services)? Most importantly, how might we mind the gap between insight and development of new offerings? The answer is simple—the problem lies in how the data and the generated insights are used to innovate. In such cases, groups tend to narrowly solve the identified problems, resulting in short-term product/service changes that lack strategic vision, or a strategic direction often at odds with the actual research insights.

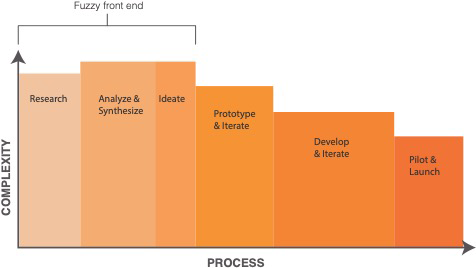

Most organizations spend time in “quick wins” and “low-hanging fruit,” which is neither revolutionary nor evolutionary—and never results in innovative solutions. In any given service–experience development, the first step is bridging the gap between the research insights and innovation strategy—identification of an offering that has commercial potential. Many refer to this as the “fuzzy front end of innovation,” which is also considered the most challenging and uncertain part of the offering development process. This is where creative ideation and idea facilitation frameworks can help. These creative ideation tools can bridge the gap between research and development.

1.3 A case for idea facilitation tools and frameworks

The role of ideation is threefold—to balance the expertise of the participating individuals with existing insights while prompting the group to imagine and envision new realities. But when ideation goes awry, it becomes a deterrent to innovation. Additionally, ideation is a key part of the fuzzy front end of innovation development. It is the gateway to identifying and developing the plausible solutions. Information gathering, sense making, and idea generation are typical tasks of the front end—having a high influence on project outcomes in terms of innovation and new-to-the-market ideas (Herstatt and Verworn, 2004).

Hence, a structured approach to idea facilitation can help achieve the maximum opportunities availed by ideation sessions: creative and innovative product/service ideas. Structured ideation frameworks can discourage linear thinking and encourage teams to think strategically and laterally—by switching perspectives, identifying multiple points of view (POVs), challenging assumptions, and contextualizing problems.

2 Four ideation frameworks

The four chosen frameworks—megatrends (Naisbitt, 1982), journey mapping jobs (adaptation of JTBD; Christensen, 2006), strategy paradoxes (Bau, 2010), and strategy canvas (Kim and Mauborgne, 2005)—enable cross-functional teams to look at the same insight from different perspectives, in some ways both contextualizing and recontextualizing the insights—generating a vast variety of ideas, avoiding cognitive inertia, and discouraging status quo thinking. These frameworks are chosen due to the transdisciplinary approach; no particular competencies such as sketching and other deep functional expertise are required, making them suitable for multifunctional teams and utilization of lateral thinking and idea generation at scale.

2.1 Journey mapping jobs

This framework is based on Christensen’s Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) work, which is based on the notion that customers do not want products—they want their jobs/tasks to be done, which essentially means products are a means to an end—in this context, the end is the completion of a job or task. In his famous example of a fast-food company wanting to boost their milkshake sales, the company was looking at other milkshake companies as a competitor, but upon analyzing customer behavior and morning breakfast routines/journey, it was discovered they were in competition with quick bite/breakfast options. That discovery reframed their “milkshake competitive market” to the broader “quick bite/breakfast market.” This reframe brought new opportunities for selling, retailing, and dispensing milkshakes that were never considered before.

This reframe of milkshakes from being a side order to a quick bite substitute explains the job-defined markets perspective compared to the traditional product category–defined markets. Job-defined markets are generally much larger than product category–defined markets. The unit of analysis for successful product is not the price point, or the customer demographic, but the job the product is intended to do (Christensen, Cook, and Hall, 2005). This framework gets more interesting in the age of the sharing economy, or experience economy. Not understanding customers’ perspectives and their task/job journey leads to a lack of understanding of the market, keeping the product stuck and disallowing product growth.

The JTBD framework is easy to understand in theory, but there is a cognitive gap in shifting the thinking from the product category–defined market to the job-defined landscape. In the last decade, JTBD has taken on a life of its own, with rigorous methods from research to product roadmaps, but they do not quite capture the essence of Christensen’s job-defined landscape—understanding the task at hand and the many alternative ways it can be accomplished, to either broaden the product delivery by creating new experiences or offering new products or services.

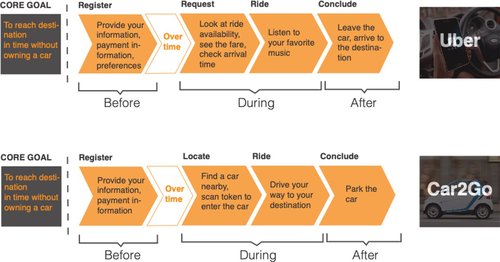

The Journey Mapping Jobs framework follows the actual JTBD thinking and helps close the gap between product category–defined market and job-defined landscape. It does so by using the customer journey–mapping structure that aids the thinking. This structure has three steps: (1) identifying the core goal—job/task, (2) mapping the customer journey of the existing solution, and (3) mapping the experience by subtracting, shifting, or adding steps.

To illustrate the point, consider ideating for an opportunity around “fast and private localized travel without the hassle of owning a car.” The core goal (job to be done) is to reach the destination without owning a car, but still be fast and private. This eliminates public transportation such as buses, trains, and trams, as they are neither fast nor private. The remaining option is the existing solution of hailing a taxi. The as-usual thinking would be to create a “better taxi service”: newer cabs, faster service, multiple payment options. This thinking narrows the solutions to the product–service category—taxi services—limiting the scope of the opportunity and consequently market share by drawing a boundary and thinking within it. But through the use of the Journey Mapping Jobs framework—first, the core customer goal is identified, followed by the analysis of the current taxi experience, and shifting, adding, and removing the steps in the journey—a new experience/service proposition is identified.

2.2 Megatrends

Megatrends are large, national, and international transformative forces that impact both consumers and businesses. They have a far-reaching impact on business, society, culture, economies, and individuals. These far-reaching consequences will play out over a decade or more. The term megatrend is usually attributed to John Naisbitt’s book Megatrends, published in 1982. They are a strategic foresight tool used to future-proof product strategy and develop disruptive product innovation.

Like other methods in foresight research, analyses of megatrends are considered more art than science. It is less about predictability and more about how prepared the organization is for the potential scenarios. These foresights and trends are based on deep insights in technology, demographics, regulations, and lifestyles, and they can be utilized to create new markets and identify white space. Although understanding the trends and their implications requires creativity and imagination, the vision and foresight cannot be based on the fantastical (Hamel and Prahalad, 1994).

Typical examples of such megatrends are demographic changes (e.g., global and national ageing and the need for care) and climate change (e.g., rethinking urban planning around the world).

This framework helps in connecting the practice-based design research insights to the larger national and international trends that have broader implications. If practice-based design research is contextual and micro, the megatrends can be considered a macro and broader perspective. Each industry might have a variation of the megatrends, but they are broad enough to encapsulate the key trends that affect every walk of life, including the businesses.

2.3 Strategy paradoxes

This framework asserts that designers approach new product–service propositions from the perspective of designing for attributes and benefits, whereas the service providers and business units within the same organization look at designing for return on investment (ROI) and corporate value. Bau (2010), the author of this strategy framework, argues that neither of the approaches are fit to direct and inspire the vague front end of product–service innovation. Instead, a third approach, “designing for strategy dichotomies and paradoxes,” may be a better fit for leading and inspiring the product–service innovation. Although the conversation about ROI and corporate value tells us what the business objectives are, it does not lead the path to how to achieve them. On the other hand, the benefits and features of a product that bring customers value are hard to translate into 1:1 financial modeling. Neither does the customer benefit/feature perspective translate into innovation.

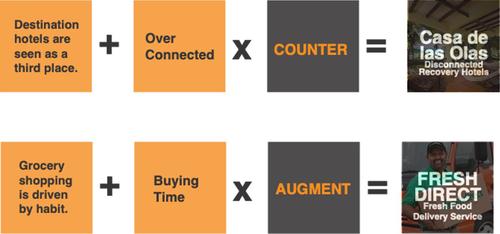

The dichotomies framework is based on bipolar opposites such as global versus local and tangible versus ephemeral. This highlights two opposing, contradictory perspectives—underlying that you have to choose one or the other. The biggest reframe of this framework is treating these dichotomies as paradoxes—undertaking both at the same time, but perhaps with varying degrees. For example, a food service may feature global cuisine with local ingredients, making it both global and local at the same time.

This framework serves four key purposes: (1) it explores open-ended problems by looking at two seemingly opposing perspectives at the same time; (2) the dichotomies and paradoxes encourage a common frame or references for multifunctional teams and encourage collaboration; (3) it enables long-term objectives and goals, beyond the current customer needs and benefits or the current business value; and (4) it forces the organization and its multifunctional teams to keep abreast of and be in tune with socioeconomic and technology trends.

These five key dichotomies and paradoxes are taken from Bau’s (2010) list. These are the most overarching ones, relevant for any sector and industry:

2.3.1 Designing for inclusion vs. designing for exclusion

Not to be taken as a framework for Diversity and Inclusion, designing for inclusion is about making services as appealing, accessible, and affordable to as many people as reasonably possible—in other words, products and services for mass market. Here, inclusion also connotes co-creation, involving customers in the development, production, distribution, and marketing of products, services, and experiences. Designing for exclusion can actually be a sound and viable strategy for some providers if executed well. The product and services that are designed to address the needs and desires of specific segments, groups, and individuals, or services that deliberately limit access and availability in different ways, may be perceived to be highly desirable, meaningful, or aspirational.

Designing for simplicity vs. designing for complexity. Designing for simplicity means that the potential in most industry sectors to provide simpler-to-understand, simpler-to-buy, and simpler-to-consume services is simply huge. This has been the overwhelming POV of most designers of various specializations throughout the world and also the premise of human-centered design (HCD). Designing for complexity sounds completely opposite to HCD yet is actually a sound and viable strategy in many industry sectors. Organizations/products that stage rich, challenging, and sophisticated experiences can help users increase their levels of physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual wellness. Most educational and training products/services fall under designing for complexity.

Designing for consistency vs. designing for flexibility. Designing for consistency means maintaining product experience consistently and with a reliable quality. The quality of operational inputs, processes, and outputs tends to vary over time, which can affect the product experience. Designing for flexibility means offering responsive, adaptable, and interconnected services, seemingly tailor-made solutions.

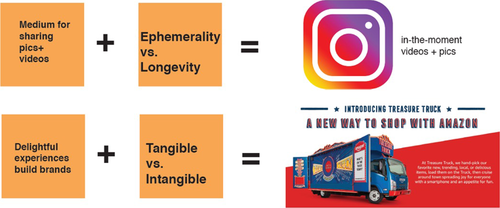

Designing for tangibility vs. designing for intangibility. Designing for tangibility means providing sensory cues and physical symbols to attributes and user benefits that are often perceived as inherently intangible. Designing for intangibility means providing benefits such as frequency, duration, and availability, which are immaterial, to differentiate the offerings and add value in a homogenous marketplace.

Designing for ephemerality vs. designing for longevity. Designing for ephemerality means creating in-the-moment experiences or providing transient benefits. It creates a sense of delight and urgency that can potentially highlight the brand value. Designing for longevity means providing timeless and long-term value to customers through products and services that do not change in value or service over time.

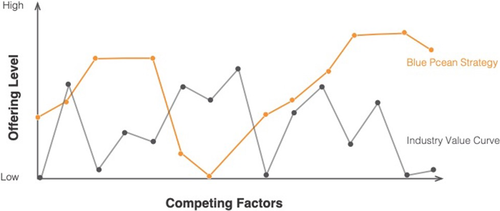

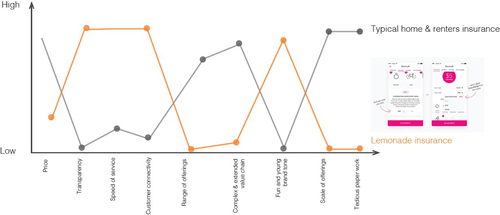

3 Strategy canvas

This is both a diagnostic tool and a strategy framework that heavily relies on visualization of “what is” to “future prospects” for a given organization. Strategy canvas serves three purposes: (1) capturing the current state of the marketplace, (2) impelling action by focusing on alternatives rather than the current competitors, and; (3) enabling visualization of how to break away from the existing reality (“red ocean”) to alternatives (“blue ocean”; Kim and Mauborgne, 2005). The visual and graphical synopsis-like aspect of the framework lends itself to ease of understanding and cross-functional collaboration.

The traditional competitive analysis and its conclusion look at how to beat the competition by doing the same thing better. But with that thinking, the organization and its business cannot reach a place where its competitors are unreachable. In contrast, unique features or competing factors can lead to the uncontested market space where the competitors become irrelevant. This framework can be used on both the macro and micro level—on the overall product offering, what is being offered, its value, and how it is being offered versus the deep feature-level product offering.

4 Idea facilitation workshop methodology

The idea facilitation workshop was tested with 50 cross-disciplinary and cross-functional participants during three separate workshops. Each workshop employed the four chosen ideation frameworks—megatrends, journey mapping, strategy paradoxes (Bau, 2010), and strategy canvas (Kim and Mauborgne, 2005).

Each workshop was three hours—starting with an introduction to the workshop and frameworks. Each team was given 30 minutes to utilize each framework, followed by a time slot of 60 minutes for getting ready to polish their ideas and present. Participants were provided with Post-it notes, butcher paper, Sharpie markers, and a packet with frameworks and their application examples. The participating professionals were a mix of nondesigners and designers with various levels of design or creative competencies, including UX designers, industrial designers, design managers, product managers, content strategists, user researchers, and program managers. Their experience with product creation and development ranged from 3 to 25 years. None of the participants had used the ideation frameworks before, although some of them were conceptually familiar with some.

The following observations were noted for each framework:

4.1 Comprehension and applicability

Megatrends. When it came to ease of understanding, the majority of participants found the megatrends framework to be the easiest one to comprehend and execute. Mostly due to familiarity with the notion of megatrends, teams found it easy to pick up and apply.

Journey mapping. Most participants were familiar with journey mapping either as a tool to visualize research findings or to explain a product–service vision. It took a little time for them to understand that this framework covered beyond ideating and finding solutions to the particular pain points. But once the concept was understood by seeing examples, they were able to apply the framework quickly. The success of the framework hinged on their familiarity with journey maps, even if they were not creatively involved in creating one.

Strategy paradoxes. This was the hardest one for most to apply conceptually. It was not difficult to understand, but the application and execution of the framework were hard for most teams, primarily because most are used to using them as dichotomies, as opposing factors rather than paradoxes, utilizing both at the same time but with variable intensity. Although the framework resulted in the most innovative ideas, that surprised even the teams.

Strategy canvas. The comprehension of the framework was medium, as were the application and execution. This framework truly utilized the skills and competencies of those with the perspective of broad offerings versus the product feature view.

4.2 Level of experience

The level of product development experience positively impacted the response and execution of the idea facilitation frameworks regardless of creative or noncreative experience. Participants with less product development experience found the frameworks difficult to understand and utilize and required more time and explanations.

4.3 Illustrative examples

Participants were appreciative of examples, which were crucial to the success of the idea facilitation—they explained the frameworks better than any description.

4.4 Cognitive and corporate inertia

The use of frameworks appeared to curtail the cognitive inertia to some extent. Some participants were observably uncomfortable, as the ideation frameworks forced them to think beyond the norm. It kept them away from the tendency of groupthink, as the ideation frameworks were taking them to unchartered ideas.

4.5 Fear of judgment

The structure of the ideation workshop with its prechosen frameworks decreased the fear of judgment, or peer conformity, if not completely eradicated it. Partly because the framework forced certain perspectives and outcomes,.it lent itself to collaboration rather than conformity.

4.6 Workshop structure

The idea facilitation workshop by design gave participants the ability to execute on the frameworks one by one, along with additional time before team presentations to rethink or augment their ideas.

4.7 Group presentations

Structured toward the end of the workshop, participants were interested in learning from other participants’ application of the frameworks and the outcomes. Overall, the participant feedback was to add group share after every framework to learn from other teams, as each team had varied outcomes.

5 Conclusion

Based on the observation of three workshops, the ideation frameworks extracted new ideas and enabled the participants to break away from cognitive as well corporate inertia. It moved the conversation beyond solving for the immediate needs and pain points, allowing for broader, innovative thinking. The idea facilitation workshop mechanism utilized frameworks in a way that did not require design competencies, making it fit for multifunctional teams and ultimately resulting in an easy-to-execute framework that influences strategic and lateral idea generation at scale. The idea is not to be tied to these particular frameworks, but to provide a structure that enables lateral thinking. These four frameworks are a few examples of how structured ideation helps in facilitating innovation.

To prove the efficacy and validity of structured ideation of these four frameworks and the idea facilitation workshop, further testing with various facilitators is required. Additionally, the ideation frameworks need to be tested in comparison with the traditional approaches.

However, beyond the success of the frameworks, to see far-reaching effects of idea facilitation, it is imperative to build organization-wide practice. Although the tools are necessary to create conditions for creative thinking and ideation, the best practices help operationalize the tasks and behaviors. Outlined are some best practices to embed idea facilitation at scale. These practices are a result of my observations and experience with facilitation:

- Beyond a one-time training workshop, make ideation part of each project: Developing an innovative point of view about the future experiences and services needs to be an ongoing project sustained by continuous ideation facilitation in collaboration with strategic research, not a secondary, once-a-year, or one-time effort. Once ideation is a core part of the fuzzy front end of all strategic projects, it will cease to be a one-time effort and will become part of each project process.

- Approach from the top down and the bottom up: There is a debate about whether change should be introduced top-down or bottom-up. For adoption of organization-wide idea facilitation, both are needed. Skilled and motivated project teams, as well as management buy-in, are both necessary. For top-down adoption, budget is an important consideration—not only the monetary budget for training, but more importantly budgeting the right amount of time for ideation. For the bottom-up approach, involvement of not just functions and individuals with existing ideation skills but exposing wider project teams for participation boosts exposure and creates encouragement.

- Start with low-risk, high-rewards projects: It is tempting to go big when introducing new processes and frameworks, but starting small and scaling fast has its benefits. It gives room to fail and experiment, without staking too much in the beginning or raising expectations. That can be a deterrent to an organization-wide adoption.

Biography

Hina Shahid a Q shaped multidisciplinary design practitioner, educator & entrepreneur, with a deep expertise on the fuzzy front end of innovation and product design. In her 15-year career she has worn my hats—researcher, strategist, designer, entrepreneur and educator—building practices and leading research and design teams in design consultancies, Fortune 500 corporations, start-ups and most recently founded a social impact initiative.