PRIORITY Trial: Results from a feasibility randomised controlled trial of a psychoeducational intervention for parents to prevent disordered eating in children and young people with type 1 diabetes

Clinical Trials Registry No. NCT04741568.

Abstract

Aims

Children and young people (CYP) with type 1 diabetes (T1D) are at increased risk of disordered eating. This study aimed to determine the feasibility and acceptability of a novel, theoretically informed, two-session psychoeducational intervention for parents to prevent disordered eating in CYP with T1D.

Methods

Parents of CYP aged 11–14 years with T1D were randomly allocated to the intervention or wait-list control group. Self-reported measures including the Diabetes Eating Problem Survey—Revised (DEPS-R), Problem Areas in Diabetes Parent Revised (PAID-PR), Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire subscales (CEBQ), Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS), clinical outcomes (e.g. HbA1c, BMI, medication and healthcare utilisation) and process variables, were collected at baseline, 1-and 3-month assessments. Acceptability data were collected from intervention participants via questionnaire.

Results

Eighty-nine parents were recruited, which exceeded recruitment targets, with high intervention engagement and acceptability (<80% across domains). A signal of efficacy was observed across outcome measures with moderate improvements in the CEBQ subscale satiety responsiveness (d = 0.55, 95% CI 0.01, 1.08) and child's BMI (d = −0.56, 95% CI −1.09, 0.00) at 3 months compared with controls. Trends in the anticipated direction were also observed with reductions in disordered eating (DEPS-R) and diabetes distress (PAID-PR) and improvements in wellbeing (WEMWBS).

Conclusions

This is the first study to have co-designed and evaluated a novel parenting intervention to prevent disordered eating in CYP with T1D. The intervention proved feasible and acceptable with encouraging effects. Preparatory work is required prior to definitive trial to ensure the most relevant primary outcome measure and ensure strategies for optimum outcome completion.

What's new?

- Given the focus on dietary intake, children and young people (CYP) with type 1 diabetes (T1D) are at increased risk of disordered eating compared to those without T1D.

- We co-designed and evaluated a novel psychoeducational parenting intervention to prevent the development of disordered eating in CYP with T1D.

- Results demonstrated that the approach was feasible and acceptable to families, with a signal of efficacy observed on key outcomes suggesting a definitive trial is warranted.

1 INTRODUCTION

The heightened prevalence of clinical eating disorders (Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa) and maladaptive eating and dieting practices (fasting, binge eating, self-induced vomiting, abuse of medications including intentional insulin omission [diabulimia]) in people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) is well documented.1 This relationship is likely to result from the interaction between T1D and the biological, psychological and social predisposing factors to developing disordered eating.2 The term disordered eating is used here to encompass both clinically significant eating disorders and eating attitudes and behaviours that impair diabetes management, psychological health and quality of life. The consequences of disordered eating are detrimental to the individual, family and the health system, resulting in increased blood glucose fluctuations, repeated hospital admissions, impaired well-being and early mortality.3, 4

The current focus of interventions has been understandably on developing specialist treatment programmes for those presenting with clinical eating disorders.5, 6 However, given the limited data on effective screening tools making early identification challenging,7 there has never been a more critical time for accessible, preventive interventions which address the underlying risk factors for disordered eating and promote healthy relationships with food and body image.8, 9 Given the importance of parents in the early detection, intervention and recovery process of children and young people's (CYP) clinical eating disorders,10 the aims of the PRIORITY Trial11, 12 were to determine whether a definitive trial of a brief and accessible parent psycho-education intervention designed to prevent the development of disordered eating in CYP with T1D is feasible and justified in terms of recruitment, retention, acceptability and signal of efficacy. Whilst a brief intervention may seem optimistic in terms of improving long-term CYP outcomes, there is precedent for single-session group-based parenting interventions to show beneficial effects.13

2 METHODS

2.1 Design

This was a feasibility randomised controlled trial (RCT) with two parallel arms, intervention or wait-list control. The sample size justification, predetermined criteria for success and information on patient and public involvement was published in our protocol.11 Ethical approval was sought from the Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales and granted by the South Birmingham Research Ethics Committee (reference 20/WM/0242) and the study was prospectively registered (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04741568).

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were (i) fluent in English or Welsh, (ii) the parent or primary caregiver of a CYP aged 11–14 years with a diagnosis of T1D and (iii) willing and able to provide informed consent and attend an online group intervention. Participants were excluded if they were currently receiving formal psychological therapy associated with their child's T1D and disordered eating, participating in another trial, or had a diagnosis of severe mental health or intellectual disability. Participants were not excluded if they had a history of eating disorders themselves.

2.3 Recruitment and sample size

Recruitment materials were disseminated to potential participants via seven National Health Service (NHS) diabetes care teams and parents provided consent for their details to be passed on to the research team. Third-sector organisations (e.g. Diabetes UK) were asked to share details of the study amongst their members. Interested participants responded directly to the research team. Recruitment was paused when the original sample size of N = 70 was reached to assess the completion rate, which was lower than anticipated so recruitment continued to enable a more precise estimate of efficacy of the intervention.

2.4 Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation, conducted by an independent statistician after baseline, was to random group allocation sequence concealed from the research team. Randomisation was stratified by insulin delivery method (e.g., multiple daily injections and insulin pump) and years since diagnosis (<2 years, ≥2 years). As is common with psychological interventions, blinding of participants was not possible but participants completed outcomes online and the outcome assessor was blind to group allocation.

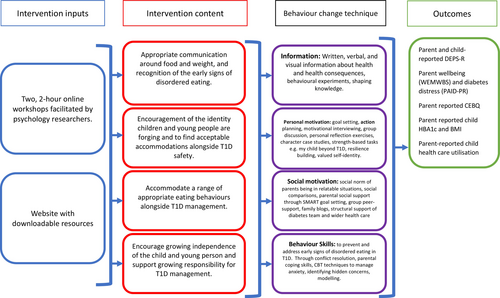

2.5 Intervention and control tasks

A comprehensive account of the development and theoretical underpinnings (Information Motivation Behavioural Skills model14) of the PRIORITY intervention and logic model has been reported previously.12 Briefly, the manualised intervention consisted of two, 2-hour online, group workshops spaced 1 week apart, facilitated by psychology researchers (including clinical psychologists and graduate psychology research assistant) and complimented by a website with downloadable resources. The content of the workshop and website focussed on appropriate communication around food and weight and recognising the early signs of Type 1 Disordered Eating (T1DE), encouraging identity formation of CYP, growing independence of T1D management and finding ways to integrate strategies into daily life (see Figure 1 for the logic model). Parents allocated to the wait-list control group were offered to attend the group workshops once final 3-month follow-up data had been collected.

2.6 Procedure

Participants provided consent and completed baseline assessments online via Qualtrics™ before being randomly allocated to the intervention or wait-list control. CYP of parents were also invited to complete online consent and the Diabetes Eating Problem Survey—Revised (DEPS-R),15 but this was not mandatory and related to a secondary aim of the study to explore validity and reliability of the parent-reported DEPS-R.16 Quantitative outcome data were collected online via Qualtrics™ at three time points; baseline, 1- and 3-month post-intervention. After completing the 3-month follow-up assessment, intervention participants were invited to participate in a qualitative interview to elicit their views and opinions of the intervention and the study generally.

2.7 Measures

- At least 30% recruitment rate among eligible parents

- At least 80% completion of the candidate primary outcome

- Acceptability of the intervention and trial to participants

- Signal of efficacy

- Ability to predict sample size and recruitment rate for definitive RCT

2.8 Demographics

Parent participants were asked to report their age, gender, ethnicity, relationship status, employment status and history of disordered eating. Parents were also asked to provide demographic and clinical information related to their child including their age, duration of T1D diagnosis, gender, height, weight, insulin regimen, HbA1c, unexpected hospital visits, nonattendance at diabetes clinical appointments, incidence of ketoacidosis and need for intravenous medication.

2.9 Outcome measures

The candidate primary outcome measure was the DEPS-R,15, 16 which was completed by parents and their children. Given the intervention was preventive and to reduce the potential for floor effects, secondary outcomes were reported by parents. These included a generic measure of child eating (the Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire [CEBQ17]), which consists of eight subscales; food responsiveness, emotional overeating, enjoyment of food, desire to drink, satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, emotional under-eating and food fussiness, the Problem Areas in Diabetes Parent Revised (PAID-PR18) and the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS19) to assess parental wellbeing, in addition to the clinical outcomes described above. A questionnaire to assess the active components of the intervention designed for this study, informed by the IMBS model,14 was also incorporated.

2.10 Acceptability

All participants receiving the intervention were invited to provide feedback using an end-of-study survey. Participants were asked to respond to statements on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree in addition to providing free-text responses to aspects of the study and intervention which worked well or could be improved.

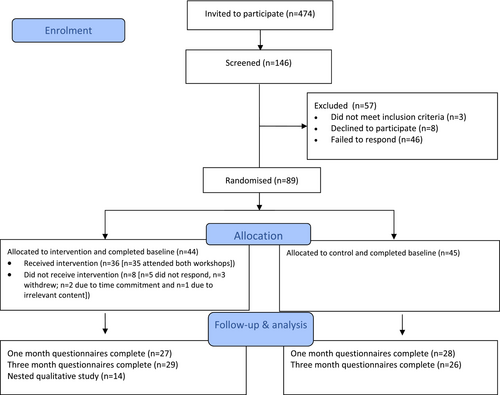

2.11 Analysis

The analysis plan was detailed in our protocol.11 Flow of participants through the trial is presented according to the CONSORT Statement 2010 extension for pilot and feasibility studies21 (Figure 2). The quantitative data were analysed descriptively, as appropriate for a feasibility study. Means and standard deviations were used to summarise normally distributed variables, medians and interquartile ranges for skewed variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Available cases were analysed following intention-to-treat principles. Missing data are reported as a proportion of missingness per outcome. For the DEPS-R, which was the only outcome missing any individual items, the mean was imputed in line with recommendations by outcome measure developers.15 Effect sizes (Cohen's d) with confidence intervals were calculated to determine a signal of efficacy at both 1 and 3 months. All quantitative data were managed and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0.21 Free-text responses to the end-of-study survey were analysed using content analysis whereby the qualitative data from each question were merged and statements that related to the acceptability of the workshop were extracted as codes, before being organised into subcategories.22

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

Of the 146 parents who were screened, 61% (N = 89) were eligible and consented (Figure 2). The majority of parent participants identified as female (89%), white (94%) and married (90%) with a mean age of 45.75 ± 5.16 years. Just under 15% of parents disclosed having a history of eating disorders. Twelve per cent of parents scored their child >20 on the DEPS-R, which is indicative of disordered eating behaviours and possible cause for concern. There was a marginally greater proportion of parents to CYP identifying as male (52%), with a mean age of 12.31 ± 1.05 years, an average age of diagnosis of 8.20 ± 3.26 years and HbA1c of 59 ± 18.92 mmol/mol (7.5 ± 3.6%). CYP participants (n = 51) who opted to complete outcomes were on average 12.12 ± 1.05 years old and more likely to identify as male (61%) and white (90%; Table 1). There were no significant differences in parent or CYP characteristics at baseline.

| Parents | Children and young people | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 89) | Intervention (n = 44) | Control (n = 45) | All (n = 51) | Intervention (n = 27) | Control (n = 24) | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 45.75 (5.16) | 45.55 (4.49) | 45.96 (5.82) | 12.12 (1.05) | 12.04 (1.09) | 12.21 (1.02) |

| Gender (n, %) | ||||||

| Male | 10 (11.2) | 5 (11.4) | 5 (11.1) | 31 (60.8) | 16 (59.3) | 15 (62.5) |

| Female | 78 (88.6) | 38 (86.4) | 40 (88.9) | 20 (39.2) | 11 (40.7) | 9 (37.5) |

| Prefer not to say/Other | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.3) | - | - | - | - |

| Ethnic group or background (n, %) | ||||||

| White British/Irish or other white | 84 (94.4) | 44 (100) | 40 (88.9) | 46 (90.2) | 25 (92.6) | 21 (87.5) |

| Mixed | 2 (2.2) | - | 2 (4.4) | 4 (7.8) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (8.3) |

| Other | 3 (3.4) | - | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.0) | - | 1 (4.2) |

| Parent-reported child age of T1D diagnosis (mean, SD) | 8.20 (3.26) | 8.52 (3.12) | 7.89 (3.39) | - | - | - |

| Parent-reported child insulin regimen (n, %) | ||||||

| Multiple daily injections | 46 (51.7) | 22 (50.0) | 24 (53.3) | - | - | - |

| Insulin pump | 28 (31.5) | 13 (29.5) | 15 (33.3) | - | - | - |

| Closed loop insulin system | 11 (12.4) | 6 (13.6) | 5 (11.1) | - | - | - |

| Other | 4 (4.5) | 3 (6.8) | 1 (2.2) | - | - | - |

| Parent-reported child HbA1c mmol/mol (mean, SD/%) | 59 (18.92)/7.5 (3.9) | 59 (21.74)/7.5 (4.1) | 59 (15.97)/7.5 (3.6) | - | - | - |

| Parent-reported child BMI (mean, SD) | 20.25 (3.57) | 19.94 (3.50) | 20.55 (3.65) | - | - | - |

| Parent marital status (n, %) | ||||||

| Married/Living with partner | 80 (89.9) | 38 (86.4) | 42 (93.3) | - | - | - |

| Separated/Divorced | 8 (9.0) | 6 (13.6) | 2 (4.4) | - | - | - |

| Single | 1 (1.1) | - | 1 (2.2) | - | - | - |

| Parent employment status (n, %) | ||||||

| Working full-time | 40 (44.9) | 15 (34.1) | 25 (55.6) | - | - | - |

| Working part-time | 36 (40.4) | 21 (47.7) | 15 (33.3) | - | - | - |

| Homemaker | 13 (14.6) | 8 (18.2) | 5 (11.1) | - | - | - |

| Parent history of disordered eating (n, %) | 13 (14.6) | 6 (13.6) | 7 (15.6) | - | - | - |

3.2 Feasibility

Of the 44 parents who were randomised to receive the intervention, 36 (82%) attended at least one workshop with 35 (80%) attending both workshops and 35 (97% of attendees) returning to attend the second workshop. Only three participants (3%) formally withdrew from the study and all were allocated to receive the intervention; two cited time commitments and one cited irrelevant content as reasons for withdrawal.

Rates of standardised outcome measure completion at 1 month and 3 months were both 62% and follow-up data (either 1 or 3 months) were available for 75% participants (Figure 2). Completion of outcomes was marginally greater for intervention participants (66%) compared with controls (58%). The only outcome with missing data was the DEPS-R because one of the 16 items was missed on both the parent (item 12) and child-reported (item 14) DEPS-R due to an error when transferring to Qualtrics™ (0.06% missingness). The error was rectified during the trial which meant for baseline, 67 parent-reported items (75.3%) and 37 CYP-reported items (72.5%), and for 1 month, 21 parent-reported items (38.2%) and 16 CYP-reported items (39.0%) were imputed in line with DEPS-R developers (imputing mean scores for missing outcomes). Rates of completion for parent-reported clinical outcomes were less consistently reported so whilst detailed (Table S1), should be interpreted with caution. Of note, the requirement for intravenous medication was not included as some parents misinterpreted this as number of multiple daily insulin injections.

3.3 Signal of efficacy

Descriptive statistics alongside Cohen's d, confidence intervals and sample sizes at each assessment are presented for all outcomes (Table 2). Whilst not powered to detect statistical significance, exploration of the descriptive statistics demonstrated that the DEPS-R (both parent [d = −0.10, 95% CI −0.63, 0.43] and child-reported [d = −0.50, 95% CI −1.26, 0.30]) and the PAID-PR (d = −0.07, 95% CI −0.60, 0.46) showed a small trend for reduction in eating problems and diabetes distress amongst intervention participants compared with controls at 3 months. Similarly, parent wellbeing also demonstrated a trend for improvement in intervention participants compared with controls at 3 months (d = 0.27, 95% CI −0.27, 0.79). Effect sizes for final follow-up data were small to moderate for intervention participants compared with controls at 3 months with most evidence of improvement for the CEBQ subscale satiety responsiveness (d = 0.55, 95% CI 0.01, 1.08), in addition to a reduction in BMI (d = −0.56, 95% CI −1.09, 0.00) though to a lesser extent when controlling for age and gender norms using BMI percentile (d = −0.44, 95% CI −0.98, 0.10).

| Outcome | Intervention M (SD) | Control M (SD) | Effect size Cohen's d (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-reported | ||||||||

|

Baseline n = 44 |

1 month n = 27 |

3 months n = 29 |

Baseline n = 45 |

1 month n = 28 |

3 months n = 26 |

1 month | 3 months | |

| Diabetes Eating Problem Survey—Reviseda |

10.99 (9.01) 10.13 (14.55) |

10.21 (8.83) 8.00 (8.00) |

9.21 (7.88) 7.00 (10.00) |

9.58 (9.61) 6.00 (10.27) |

9.84 (7.68) 8.80 (8.88) |

10.07 (9.15) 8.77 (7.00) |

0.04 (−0.48, 0.57) | −0.10 (−0.63, 0.43) |

| Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaireb | ||||||||

| Food responsiveness | 2.81 (1.10) | 2.65 (1.05) |

2.51 (0.92) 2.40 (1.00) |

2.81 (0.90) | 2.99 (0.94) | 3.00 (0.95) | −0.34 (−0.87, 0.20) | −0.52 (−1.05, 0.02) |

| Emotional overeating | 2.54 (0.90) | 2.36 (0.91) | 2.34 (0.73) |

2.18 (0.95) 2.00 (0.88) |

2.45 (0.87) |

2.33 (0.88) 2.25 (0.81) |

−0.07 (−0.60, 0.46) | 0.01 (−0.52, 0.54) |

| Enjoyment of food |

4.00 (0.75) 4.00 (0.75) |

3.89 (0.77) 4.00 (0.75) |

3.82 (0.74) |

4.04 (0.79) 4.25 (1.50) |

4.16 (0.76) 4.38 (1.00) |

3.99 (0.84) 4.25 (1.50) |

−0.35 (−0.88, 0.18) | −0.22 (−0.74, 0.32) |

| Desire to drink |

2.16 (0.79) 2.00 (1.00) |

2.28 (0.90) 2.33 (1.00) |

2.17 (0.92) 2.00 (0.83) |

2.07 (0.78) 2.00 (1.33) |

2.25 (0.81) 2.33 (1.00) |

2.26 (0.73) 2.33 (0.33) |

0.04 (−0.49, 0.56) | −0.11 (−0.64, 0.42) |

| Satiety responsiveness |

2.35 (0.75) 2.40 (1.00) |

2.44 (0.73) | 2.47 (0.60) | 2.13 (0.66) | 2.15 (0.62) | 2.17 (0.47) | 0.43 (−0.11, 0.96) | 0.55 (0.01, 1.08) |

| Slowness in eating |

2.15 (0.69) 2.00 (0.75) |

2.16 (0.69) | 2.07 (0.70) |

1.87 (0.65) 1.75 (0.75) |

1.95 (0.67) | 2.00 (0.59) | 0.31 (−0.23, 0.84) | 0.11 (−0.42, 0.64) |

| Emotional under-eating | 2.74 (0.71) | 2.57 (0.76) | 2.64 (0.75) | 2.36 (0.75) | 2.45 (0.80) | 2.30 (0.76) | 0.15 (−0.38, 0.68) | 0.45 (−0.09, 0.98) |

| Food fussiness | 2.68 (1.05) | 2.50 (1.03) | 2.47 (1.08) | 2.51 (1.06) | 2.54 (1.07) | 2.48 (0.92) | −0.04 (−0.57, 0.49) | −0.01 (−0.54, 0.52) |

| Problem areas in diabetes parent revisedc | 38.41 (19.67) | 34.63 (17.59) | 34.61 (18.62) |

38.19 (16.94) 35.00 (23.13) |

39.91 (16.58) | 35.96 (18.20) | −0.31 (−0.84, 0.23) | −0.07 (−0.60, 0.46) |

| Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scaled | 45.66 (8.43) | 48.19 (9.95) | 49.34 (7.36) | 46.80 (9.67) | 48.96 (8.21) | 47.20 (8.68) | −0.08 (−0.61, 0.45) | 0.27 (−0.27, 0.79) |

| Child-reported | ||||||||

| n = 27 | n = 22 | n = 11 | n = 24 | n = 19 | n = 16 | |||

| Diabetes Eating Problem Survey—Reviseda |

10.82 (9.59) 9.60 (10.67) |

10.72 (10.96) 7.00 (15.62) |

9.45 (8.54) | 13.19 (9.94) |

15.30 (12.07) 9.60 (18.67) |

15.63 (14.46) 7.74 (26.72) |

−0.40 (−1.01,0.23) | −0.50 (−1.26, 0.30) |

- a Range 0–80 with higher scores indicative of more disordered eating behaviour.

- b Range 15–35 dependent on number of items within subscale with higher scores indicating more specific eating behaviour.

- c Range 0–100 with higher scores indicative of greater problem areas.

- d Range 14–70 and higher scores indicating greater positive mental well-being.

3.4 Process evaluation

The intervention was based on the IMBS model, and a questionnaire was designed to assess psychological factors contributing to any changes in primary and secondary outcomes. Results demonstrated that the intervention improved the behavioural change targets of motivation (d = 0.88, 95% CI 0.31, 1.42) and behavioural skills (d = 0.69, 95% CI 0.13, 1.22) compared with controls at 3 months. Information looked to have improved at 1 month but the magnitude of effect was not sustained for final follow-up (Figures S1–S3).

3.5 Acceptability

Twenty-nine participants (66%) completed the optional, end-of-study feedback questionnaire (Table 3). The majority of participants (82%–97%) found the intervention beneficial, well-organised, nondistressing and met their expectations. Although in the minority, 41% of parents disclosed concerns about having their child complete questionnaires about diabetes eating problems, which was the greatest aspect of discontent.

| Statement item | Proportion agreed or strongly agreed (%) |

|---|---|

| I found taking part in the study to be easy | 96.6 |

| The workshop was well organised and ran smoothly | 96.6 |

| I believe that a psychological workshop could help to understand and manage disordered eating in children with type 1 diabetes | 93.1 |

| I found taking part in the study to be convenient | 89.7 |

| The workshop felt the right length of time | 89.7 |

| I felt safe and comfortable during the workshop | 89.7 |

| On the whole, I found the workshop to be helpful | 89.7 |

| I found taking part in the study to be interesting | 86.2 |

| I found taking part in the study to be worthwhile/beneficial | 86.2 |

| I found it helpful to have other parents in the workshop to share ideas with | 82.8 |

| The workshop met my expectations | 82.8 |

| I would recommend the workshop to other parents of children with type 1 diabetes | 82.8 |

| I found the study website and downloadable resources helpful | 72.4 |

| I had concerns about having my child completing the questionnaires about diabetes eating problems | 41.4 |

| I found taking part in the study to be time consuming | 10.3 |

| Taking part in the workshop felt distressing and burdensome for me | 3.4 |

Content analysis of free-text responses to the most helpful aspects of the intervention demonstrated two overlapping themes regarding having an appreciation for the time and opportunity to reflect and learn from one another. These were as follows: Increased awareness and practical skills and Sharing experiences and learning from other parents. Most parents reported benefitting from Increased awareness and practical skills, for example: ‘Given the language and skills to talk to child, analysis of what “type” of parenting styles I tend to use and how to change that’, ‘The strategies given to use after the workshop have been useful to use with both my children, not just the one with T1D, so very helpful to us as a whole family’, as well as information specifically regarding disordered eating ‘Understanding about disordered eating and diabetes. Problem solving advice’. Parents reflected on how stage of diagnosis impacted their experience, for example ‘Because we took part very soon after diagnosis, it accelerated our learning around diabetes in young teenagers’. For the theme Sharing experiences and learning from other parents, most parents again reported benefiting from the group intervention ‘I benefit from strength in numbers and finding my tribe!’ and ‘Hearing other parents divulge their struggles so realising we are not alone’. The overarching theme of having the time for discussion with both health professionals and parents was reported by the majority of parents, for example ‘Hearing other parents' experiences, hearing from trained professionals on how to deal with situations’ and ‘Opportunity to discuss concerns with professionals and other parents. Getting new ideas/perspectives on issues. Feeling less alone because others are going through similar difficulties’.

Only three parents provided feedback on aspects of the intervention that might be improved which centred around Duration of the workshops and Scope of intervention content. Three parents found the sessions too long, and two other parents suggested spreading the information over more sessions ‘There was a lot of information to take in/process - could consider spreading sessions over 3 rather than 2 evenings?’. Three parents reported that whilst they found aspects of intervention informative, they felt that more comprehensive guidance would be required to really improve their confidence in managing disordered eating ‘I could do with more detailed help in learning how to broach difficult subjects like this. Pretty tricky in real life not to make things worse’ and ‘It was informative in a small way but I didn't find it helped at all re my child's eating. It was more about parent behaviour and I didn't need what it offered’.

4 DISCUSSION

This original study was designed in response to a call from individuals, families, clinicians and academics for early interventions to prevent the development of clinical eating problems in CYP with T1D.8 We have demonstrated that a novel, co-designed, brief, psychoeducational intervention aimed at parents to prevent disordered eating in CYP aged 11–14 years with T1D was feasible and acceptable to the intended population. We met the majority of our progression criteria; we were able to recruit and randomise 89 parents (recruitment rate 31% of those invited to participate assuming diabetes services adhered to inclusion criteria, and 61% of those screened were eligible), with 62% completing candidate primary outcomes at 1 and 3 months. Of the parents randomised to receive the intervention, 80% attended both workshops, with 97% of those who attended the first workshop returning for the second. These results compare favourably to other recently conducted brief interventions aimed at adolescents with T1D and disordered eating for which uptake and intervention engagement were reported at 19% and 27%, respectively.23

A signal of efficacy was observed with trends moving in the anticipated direction on all outcomes and process variables. The effect size and confidence intervals were most convincing for the Child Eating Behaviour subscale ‘Satiety Responsiveness’ which is perhaps unsurprising given the importance of attuning to feelings of fullness and its link with healthier eating behaviours and weight.24 Parental feedback was largely positive, with the majority of participants describing the intervention as beneficial, well-organised, nondistressing and meeting their expectations. Parents seemed particularly positive about the opportunity to learn from and discuss concerns with professionals and other parents. Some areas for improvements were highlighted by a small number of parents which included offering shorter, more frequent sessions and more comprehensive advice on how to manage eating disorders. Whilst important, these issues were only raised by three participants, which likely indicates that the majority found the current format and preventive focus of the intervention acceptable. Concerns were raised more frequently by parents regarding child outcome reporting of the DEPS-R, which is supported by the in-depth qualitative findings.25 However, this was a secondary aim of the project to determine whether parent-reporting of disordered eating is valid and reliable. Results of the reliability and validity of parent-reported DEPS-R are outside the scope of this article and will be reported elsewhere. Finally, we now have the ability to predict sample size for a future trial derived from the standard deviation estimates obtained.

Whereas these criteria indicated a ‘go’ for definitive trial, failure to reach any would require mitigation to give confidence around the feasibility of such a trial. The only unmet criteria was outcome measure completion and whilst 62% is lower than the ambitious predefined progression criteria of 80%, this rate falls comfortably within those observed in health behaviour change trials which can vary considerably.26 That said and following encouraging discussions with our Trial Steering Committee, preparatory work for a definitive trial will be undertaken with families to agree on the most relevant primary outcome measure (e.g. perhaps Satiety Responsiveness is more appropriate than the parent-reported DEPS-R given the preventive nature of the intervention and more convincing effect size) and to ensure strategies for engagement and completion, particularly in the control group.

Whilst interventions exist for treating individuals with T1D and eating disorders,5, 6 this study is the first of its kind to develop and evaluate an intervention for parents to prevent disordered eating in CYP with T1D and provides encouraging results which are of considerable clinical interest. We have utilised robust, RCT methodology, including a prospectively published protocol, independent randomisation and blinded outcome assessment. However, there are some limitations notwithstanding considerations described above. Whilst parent-reported CYP clinical characteristics were measured, these were of questionable validity. For example, several participants confused the need for intravenous medication with regular daily insulin injections, in addition to some parents reporting their CYP as shorter at 3-month follow-up compared with baseline possibly invalidating BMI and the result regarding reduction in intervention participants. The follow-up intervals of 1- and 3 months meant a lack of variability in HbA1c and healthcare utilisation reporting indicating that biomedical outcomes should be obtained from hospital records for any definitive trial. Additionally, the lack of demographic diversity within the participants which may reflect the geographic region predominantly recruited from, limits the generalisability of the findings. Subsequent patient and public involvement is currently underway with underserved groups to explore acceptability of the recruitment materials and study more broadly.

To conclude, this novel, manualised preventive intervention has demonstrated feasibility and acceptability amongst parents of CYP with T1D with encouraging results observed on key outcome measures and process variables in the anticipated direction. Results suggest that a definitive trial is warranted with consideration of routes to aid implementation within routine diabetes services which will prove critical to ensure rapid uptake in the event of the intervention demonstrating clinical and cost-effectiveness.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by Diabetes UK (award number 19/0006123).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no competing interests to report.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Participants were informed that anonymised data may be shared with other research teams. Therefore, anonymised data are available on reasonable request for research teams by contacting [email protected], but are not able to be uploaded for free access given these restrictions.