‘Is Insulin Right for Me?’: Web-based intervention to reduce psychological barriers to insulin therapy among adults with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes—A randomised controlled trial

TRIAL REGISTRATION: ACTRN12621000191897.

Abstract

Aims

To test ‘Is Insulin Right for Me?’, a theory-informed, self-directed, web-based intervention designed to reduce psychological barriers to insulin therapy among adults with type 2 diabetes. Further, to examine resource engagement and associations between minimum engagement and outcomes.

Methods

Double-blind, two-arm randomised controlled trial (1:1), comparing the intervention with freely available online information (control). Eligible participants were Australian adults with type 2 diabetes, taking oral diabetes medications, recruited primarily via national diabetes registry. Exclusion criteria: prior use of injectable medicines; being ‘very willing’ to commence insulin. Data collections were completed online at baseline, 2-week and 6-month follow-up. Primary outcome: negative insulin treatment appraisal scale (ITAS) scores; secondary outcomes: positive ITAS scores and hypothetical willingness to start insulin. Analyses: intention-to-treat (ITT); per-protocol (PP) examination of outcomes by engagement. Trial registration: ACTRN12621000191897.

Results

No significant ITT between-arm (intervention: n = 233; control: n = 243) differences were observed in primary (2 weeks: Mdiff [95% CI]: −1.0 [−2.9 to 0.9]; 6 months: −0.01 [−1.9 to 1.9]), or secondary outcomes at either follow-up. There was evidence of lower Negative ITAS scores at 2-week, but not 6-month, follow-up among those with minimum intervention engagement (achieved by 44%) compared to no engagement (−2.7 [−5.1 to −0.3]).

Conclusions

Compared to existing information, ‘Is insulin right for me?’ did not improve outcomes at either timepoint. Small intervention engagement effects suggest it has potential. Further research is warranted to examine whether effectiveness would be greater in a clinical setting, following timely referral among those for whom insulin is clinically indicated.

What's new?

- Psychological barriers to insulin are common among adults with type 2 diabetes, and associated with delayed uptake. Existing interventions, for example, optimised models of care, are challenging for resource-limited health systems.

- Designed to reduce psychological barriers, ‘Is Insulin Right for Me?’ is a novel, theory-informed, self-directed, web-based intervention.

- This randomised controlled trial identified no beneficial effect of the intervention relative to control.

- While study engagement was low, intervention engagement was associated with reduced negative insulin appraisals.

- Future exploration of barriers to, facilitators and predictors of, engagement will inform intervention refinement and implementation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Among adults with type 2 diabetes, initiation of insulin is often delayed beyond clinical need,1, 2 contributing to maintenance of sub-optimal glycaemia and associated serious long-term complications.3 Multi-faceted barriers to insulin uptake exist at the systemic, health professional, and individual levels.2, 4, 5 National diabetes associations have called for the identification and implementation of novel strategies to overcome these barriers.1, 6 There is promising evidence for the beneficial effects of multidisciplinary models of care, upskilling health professionals, specialist feedback, and automated reminders in addressing barriers to insulin prescription.4 However, many adults with type 2 diabetes decline insulin therapy upon prescription,3, 7, 8 and individuals' willingness to start insulin contributes significantly to the prediction of timely insulin initiation, independent of the model of care received.9

Hesitancy to initiate insulin therapy, sometimes referred to as ‘psychological insulin resistance’,10 is based on negative attitudes, or beliefs, about insulin, including perceiving insulin as unnecessary or ineffective, concerns about insulin side effects, physical and social impacts, as well as what insulin represents (symbolically) for health and identity.5, 11 In response, collaborative consultation strategies are recommended, with injection demonstrations, explanation of treatment benefits, and discussion of concerns about insulin having been retrospectively reported as facilitators of insulin initiation.12-14 However, these strategies have not been evaluated rigorously, nor implemented routinely. Clinicians report limited time, skills, or confidence to address such concerns,2, 4 and people with type 2 diabetes report that their psychological barriers are not addressed.15 Further, implementation of interventions designed to address psychological insulin resistance is challenged by resource-limited heath systems, and/or low uptake among people with type 2 diabetes within a clinical setting.16-18

Scalable and accessible interventions (external from, or supplementary to, clinical care) may provide opportunity to address individuals' concerns about insulin while minimising burden on healthcare resources. Web-based interventions enable wide reach and equitable access across the type 2 diabetes population, and have demonstrated benefits for health behaviours and outcomes, when grounded in health and behaviour change theory.19 However, the theoretical underpinnings and evaluation of widely available insulin-specific online information is limited or unknown. Therefore, we developed and piloted ‘Is Insulin Right for Me?’, a theory-informed, brief and self-directed, web-based resource, designed to reduce salient psychological barriers to insulin therapy among adults with type 2 diabetes.20, 21 Our pilot two-arm RCT (N = 35) among Australians adults with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes showed the study design (including online recruitment and participation) to be feasible, and the intervention acceptable.21 Further, there was preliminary evidence of likely reductions in psychological barriers to insulin, when compared to freely available online information.21

We aimed to examine the effect of ‘Is Insulin Right for Me?’ on negative attitudes towards insulin therapy, as well as receptiveness to insulin (positive insulin appraisals and willingness to commence insulin), among Australian adults with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes reporting hesitancy towards starting insulin in the future. In addition, we explored engagement with the intervention, and conducted per-protocol (PP) analyses to examine associations between minimum engagement and outcomes.

2 METHODS

The registered study protocol (ACTRN12621000191897) is detailed elsewhere,22 and was approved by Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: 2020–073). A double-blinded, parallel-group, two-arm RCT (1:1 ratio) was conducted, with baseline, 2-week and 6-month follow-up data collection via online survey (hosted by Qualtrics™), and a 2-week online intervention exposure period. Deviations from protocol were: (1) minimum enrolled sample size increased due to the greater-than-expected 2-week attrition rate (see below); (2) relatedly, the recruitment period was extended by 1 week; (3) addition of PP analysis.

2.1 Participants and recruitment

Eligibility criteria (assessed via self-report) were: adults, aged 18 to 75 years; Australian residence; type 2 diabetes; use of oral hypoglycaemic agents; access to an internet-enabled device. Clinical recommendation for insulin treatment was not an inclusion criterion. Exclusion criteria were: experience self-administering an injectable treatment for any illness or condition; reporting at recruitment that they were already ‘very willing’ to initiate insulin therapy;23 and prior participation in the pilot study.21

Participants were recruited (11 January–17 March 2021) primarily via direct invitation (email or mail) and subsequent reminder (at 2 weeks) sent to a random sample of National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) adult registrants, with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (stratified by state/territory), who had consented to being notified about research opportunities. The NDSS is an initiative of the Australian Government administered by Diabetes Australia, enhancing access to services, support and subsidised diabetes products. Registrants include more than 1.2 million people with a health professional confirmed diagnoses of type 2 diabetes. The total NDSS invitations distributed (2000 mail; 21,000 email) was informed by the anticipated response rate (8%)24, 25 and enrolment rate (43%),20 as well as the actual recruitment and 2-week attrition rates. The study was also promoted via online advertising in e-newsletters and social media, and via national and state-based diabetes organisations and health professional networks. Participants who completed all three assessments were entered into a prize draw to win one of 20 AUD$100 gift vouchers.

2.2 Procedure

A schedule of enrolment, intervention and assessment is detailed in the published protocol.22 Potential participants were directed to a study website (via Qualtrics™) with basic information and eligibility screening questions, followed by online provision of full study information and consent form. Eligible, consenting, enrolled participants were randomised and invited (via email) to access the allocated web-based resource within a 2-week period (with a 1-week reminder). Given that the intervention was designed for self-determined engagement, and there was no reason to think that all barriers would be salient to all participants, no instructions were provided regarding the level of resource engagement expected. Two-week and 6-month follow-up survey access was sent via email, and available for completion for 14 and 21 days respectively, with weekly reminders sent to those who had not completed the surveys. Study end was marked by submission of the 6-month survey or non-submission at 22 days.

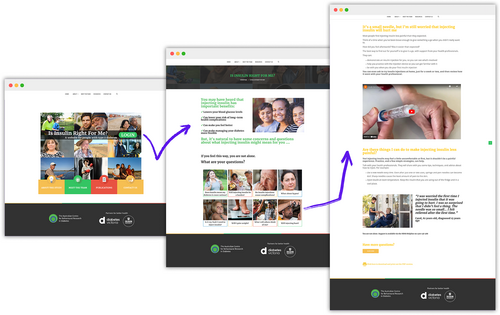

2.2.1 Intervention arm

Participants in the intervention arm gained access to the ‘Is insulin right for me?’ web-based resource. The evidence-based intervention development process, and a detailed description of the intervention content, graphic design and behaviour change techniques employed, are published elsewhere.20-22 The intervention homepage includes eight themes, each relating to a known psychological barrier to insulin and framed as a question (See Figure 1). Each barrier was identified via literature search and mapped to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF; eight relevant domains: knowledge; skills; social role and identity; beliefs about capabilities; beliefs about consequences; environmental context and resources; social influences; emotion).26 Relevant behaviour changes techniques (BCTs) were identified for each barrier.27 The relevance of the identified barriers, TDF domains and BCTs were peer-reviewed by an external panel (n = 4, experts in health psychology and behaviour change). Content responding to each psychological barrier was developed, comprising eight brief webpages (200–500 words each), including appropriate application (e.g., text, imagery, quizzes, videos).20 Content and design was refined following consumer feedback (cognitive debriefing interviews, n = 6) and external expert peer review (n = 5). At the outset, the intervention was designed as a self-directed tool, with participants free to engage in as many of the eight themes as they deemed relevant to them. The intervention website also included brief information about the benefits of insulin, as well as links to freely available resources (see Control arm) and study information that was made available across both study arm resources.

2.3 Control arm

Control arm participants were directed to a static webpage including links to text-based NDSS-published factsheets/booklets (freely available via https://www.ndss.com.au/): Understanding type 2 diabetes, Insulin (not diabetes type specific), Medications for type 2 diabetes, Blood glucose levels and monitoring, Diabetes-related complications, Hypoglycaemia, Peer support for diabetes, Concerns about starting insulin, and Starting Insulin. Only the latter two resources specifically discuss psychological barriers to insulin.

2.4 Outcomes

The co-primary outcome was the between-arm difference in mean Negative Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale (ITAS) subscale scores,28 at 2-week and 6-month follow-up, adjusted by baseline scores. The ITAS is a validated 20-item scale. Participants rate their agreement with 16 negative and 4 positive statements about insulin (5-point scale: 1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 5 = ‘strongly disagree’).28 Summed items form Negative (range: 16–80) and Positive (range: 4–20) subscale scores, with higher scoring indicating greater endorsement of negative and positive insulin appraisal respectively. Based on our prior research in Australian clinical and non-clinical samples,9, 21, 29 it was hypothesised that a statistically significant difference in mean Negative ITAS scores of ≥4 points (approximately 0.5 standard deviations) would be observed at 2 weeks, favouring the intervention arm, and sustained at 6 months.

Secondary outcome measures were between-arm differences, at 2-week and 6-month follow-up, after adjusting for baseline score, in: (a) positive insulin appraisals (ITAS Positive);28 and (b) hypothetical willingness to begin insulin therapy, as measured by a single item (“If your doctor recommended that you start insulin, how willing would you be to take it?”; 4-point scale: not at all, not very, moderately, very).23

Process evaluation variables include validated psychosocial measures of diabetes-specific distress, illness perceptions, self-efficacy, and knowledge (see Table S1), and; study-specific measures of insulin-related knowledge, change in insulin use status, and self-reported resource engagement. For the intervention arm, website analytics data were collected: resource visits (session frequency/duration), ‘barrier’ webpage views (frequency, scroll depth), interaction with three embedded quizzes, and, for the overall sample, total number of views (and average viewing time) for two embedded YouTube videos.

2.5 Sample size

The minimum sample size was pre-determined as N = 250 (n = 125 per arm); sufficient to detect a minimally important between-arm difference of a half standard deviation in Negative ITAS scores at 85% power and 0.05 significance level using a two-sided test. Assuming a 20% 2-week attrition rate (informed by the pilot RCT),21 and a further 20% attrition at 6 months, the required enrolled sample was N = 392. The minimum enrolled sample size was adjusted to N = 454 following preliminary, blinded, inspection of 2-week survey completion data which informed a revised upper anticipated attrition rate (31%).

2.6 Randomisation

Participants were stratified by gender and randomised using randomly permuted block sizes of 4, 6 or 8. The randomisation sequence was computer generated and the allocation fully concealed from investigators and participants. SB managed all contact with participants, including online resource and follow-up survey access details, as well as reminder emails, but did not have access to data. EEH monitored incoming survey data and was blinded to study arm allocation. The statistician, participants, and other investigators remained blinded to study arm allocation throughout data collection and primary analyses.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Quantitative analyses were performed using Stata/SE 16.1. Descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline characteristics, resource engagement, and psychological outcomes at each timepoint. Baseline data were assessed visually by allocation, by loss to follow-up, and by minimum engagement for imbalances.

An intention-to-treat (ITT) approach was adopted. A linear mixed-effects model was used to estimate the between-arm differences in mean Negative ITAS scores at 2 weeks and 6 months using restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Treatment arm and data-wave were included as fixed effects in the model. Random effects were used to account for repeated participant measures. Sensitivity analysis was conducted (via pattern-mixture modelling) to test the robustness of the missing data assumption. Positive ITAS Scores (secondary outcome), and continuous psychosocial process evaluation outcomes were analysed using the same modelling approach. An ordinal logistic mixed-effects model was used to quantify differences in the willingness to begin insulin therapy (secondary outcome) between arms at each follow-up timepoint.

Per-protocol analyses were conducted to investigate the effect of protocol engagement on primary and secondary outcomes. Three engagement groups were devised to reflect resource access: engaged intervention group (≥1 barrier page of the intervention website accessed); engaged control group (self-reported access of the control resources at 2-week follow-up); non-engaged group (remainder of participants). Minimum engagement criteria reflect the original intention: that is, for the intervention to be a brief, self-directed tool, allowing for individualised selection and access of salient barrier pages, with minimal burden on the participant to engage in materials they did not deem to be relevant. Inverse probability treatment weights (IPTW) were created to adjust for group imbalances identified at baseline.30 Selected confounders were: age, gender, employment status, education level, diabetes duration, complications, and willingness to start insulin. Inverse probability treatment weights were applied to the generalised linear mixed-effects model as above. Ordinal logistic regression models for outcome willingness to begin insulin therapy were not conducted due to small cell sizes leading to non-convergence.

3 RESULTS

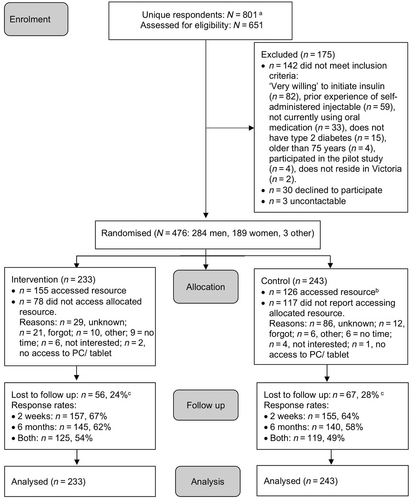

Participant flow is summarised in Figure 2 and sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. In total, 476 participants were enrolled (intervention n = 233; control n = 243), with n = 123 (26%) lost to follow-up (neither 2-week nor 6-month survey completed). Two participants started insulin during the study (intervention n = 1, control n = 1). No adverse events related to study participation were disclosed.

| Total | Control | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 476 | n = 243 | n = 233 | ||||

| Missing | Missing | Missing | ||||

| Gender: Women | 0 | 189 (40) | 0 | 97 (40) | 0 | 92 (40) |

| Age, years | 0 | 66 [58–70] | 0 | 65 [58–70] | 0 | 66 [58–70] |

| Education: University degree | 0 | 192 (40) | 0 | 93 (38) | 0 | 99 (43) |

| Employment status: Employed | 1 | 180 (38) | 0 | 88 (36) | 1 | 92 (40) |

| Language spoken at home: English | 1 | 450 (95) | 0 | 235 (97) | 1 | 215 (93) |

| Diabetes duration, years | 0 | 13 [8–18] | 0 | 12 [8–17] | 0 | 13 [9–18] |

| Diabetes complications: ≥1a | 0 | 198 (42) | 0 | 101 (42) | 0 | 97 (42) |

| Self-reported HbA1c in past 12 m | ||||||

| % | 204 | 7.3 ± 1.4 | 91 | 7.4 ± 1.4 | 113 | 7.2 ± 1.3 |

| Mmol/mol | 204 | 56 ± 15 | 91 | 57 ± 16 | 113 | 55 ± 14 |

| Current glucose-lowering medications | 5 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Metformin | 328 (71) | 166 (71) | 162 (72) | |||

| Sulphonylureas | 103 (22) | 50 (21) | 53 (23) | |||

| DPP4 Inhibitor | 77 (17) | 35 (15) | 42 (19) | |||

| SGLT-2 Inhibitor | 100 (22) | 55 (24) | 45 (20) | |||

| Combined Metformin & SGLT-2 | 55 (12) | 29 (13) | 23 (11) | |||

| Combined Metformin & DPP4 | 84 (19) | 42 (18) | 42 (19) | |||

| Combined Metformin & Sulphonylureas | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | |||

| Combined SGLT-2 & DPP4 | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Glucose-lowering tablets per day | 17 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 10 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 7 | 2.1 ± 1.1 |

| HCP discussion of insulin: Yes | 1 | 63 (13) | 0 | 38 (16) | 1 | 25 (11) |

| Insulin recommended previously: Yes | 1 | 4 (0.8) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 1 | 2 (0.8) |

| Diabetes knowledge (DKT) | 0 | 68.0 ± 16.9 | 0 | 68.2 ± 16.9 | 0 | 67.7 ± 16.9 |

| Diabetes Distress (PAID) | 2 | 27.5 ± 23.2 | 1 | 27.5 ± 23.7 | 1 | 27.6 ± 22.8 |

| Diabetes self-efficacy (CIDS-2) | 1 | 83.6 ± 9.7 | 0 | 83.3 ± 9.8 | 1 | 83.9 ± 9.5 |

- Note: Data are Mdn [IQR], M ± SD, or n (%). DKT: Diabetes Knowledge Test—True/False Version, range = 0–100; PAID: Problem Areas in Diabetes, range = 0–100; CID-2: Confidence In Diabetes Self-care questionnaire for non-insulin-treated, range = 0–100. Higher scores indicating greater knowledge.

- a Kidney disease, retinopathy, neuropathy, heart disease, stroke, vascular disease, sexual dysfunction.

3.1 Intention-to-treat analyses

No between-arm differences in Negative ITAS scores were observed at either 2-week (Mdiff [95% CI]: −1.0 [−2.9 to 0.9]) or 6-month (−0.01 [−1.9 to 1.9]) follow-up. Nor were differences observed for Positive ITAS scores or the proportion reporting being ‘not at all willing’ to start insulin (secondary outcomes; Table 2). Overall, a reduction in negative insulin appraisals was observed at 2 weeks (Mdiff [95% CI]: −3.6 [−4.7 to −2.6]), and 6 months (−4.3 [−5.5 to −3.2]), relative to baseline. Similarly, there was minimal increase in willingness to initiate insulin (Table S2). Table S1 details psychosocial outcomes by arm and timepoint, with no meaningful between-arm differences identified at either follow-up.

| Outcome | Time point | Control | Intervention | Mean difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 243 | N = 233 | (95% CI)a | ||||

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | |||

| Negative insulin appraisals (ITAS) | Baseline | 243 | 53.2 ± 8.9 | 232 | 53.0 ± 9.5 | Ref |

| 2 weeks | 155 | 49.3 ± 9.7 | 157 | 48.6 ± 9.0 | −1.0 (−2.9 to 0.9) | |

| 6 months | 139 | 48.6 ± 9.4 | 142 | 48.6 ± 10.0 | −0.01 (−1.9 to 1.9) | |

| Positive insulin appraisals (ITAS) | Baseline | 243 | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 232 | 14.1 ± 2.2 | Ref |

| 2 weeks | 155 | 14.7 ± 2.3 | 156 | 14.4 ± 2.2 | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.3) | |

| 6 months | 138 | 15.0 ± 2.3 | 142 | 14.3 ± 2.4 | −0.4 (−0.9 to 0.07) | |

| n | N (%) | n | N (%) | Odds ratio [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothetical willingness to initiate insulin: not at all willing | Baseline | 243 | 34 (14) | 233 | 41 (18) | Ref |

| 2 weeks | 154 | 14 (9) | 157 | 14 (9) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.7) | |

| 6 months | 140 | 13 (9) | 144 | 12 (8) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.2) |

- Note: ITAS: Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale, Negative subscale range = 16–80, Positive subscale range = 4–20. Higher scores indicate more of the concept assessed.

- a ITT analysis: n = 475.

3.2 Resource engagement

Figure 2 details access to the allocated web-based resources, and, where available, reasons for not doing so. Intervention arm participants who accessed their allocated resource (67%, n = 155) spent a Mdn [IQR] time of 12 [4, 25] minutes browsing across sessions (1 [1, 2]; range = 1–6). Table 3 details ‘barrier’ webpages accessed, scroll depth, and quiz engagement for intervention arm participants. Minimum engagement (i.e., visited ≥1 ‘barrier’ webpage) was determined for 44% (n = 102) of intervention arm participants, with n = 20 visiting one barrier webpage only, and n = 33 visiting all eight. Where relevant webpages were accessed, high engagement was observed as indicated by scroll depth and quiz interaction (Table 3). A video demonstration of injecting insulin generated 23 views (average view duration: 26 of 32 seconds, 81%), and a video focused on diabetes progression generated 25 views (average view duration: 47 of 76 seconds, 63%).

| Barrier (webpage) title | Unique views | Scroll depth: ≥75%a | Quiz engagementa |

|---|---|---|---|

| No barrier page visited | 53 (34) | - | - |

| “Does insulin mean my diabetes is more serious?” | 88 (57) | 66 (75) | 80 (91) |

| “Will injecting insulin be a burden?” | 68 (44) | 56 (82) | - |

| “Will I gain weight?” | 65 (42) | 52 (80) | 56 (86) |

| “Do insulin injections cause complications?” | 64 (41) | 42 (67) | - |

| “What about Hypos?” | 63 (41) | 47 (75) | 46 (73) |

| “Will injecting hurt?” | 58 (37) | 52 (90) | - |

| “What will others think of me?” | 51 (33) | 40 (78) | - |

| “Is it my fault I need to inject insulin?” | 48 (31) | 40 (83) | - |

- Note: Data are n (%). Scroll depth refers to the percentage of the webpage viewed by those participants who accessed the specified barrier webpage.

- a Proportion relative to unique views for that barrier.

3.3 Per-protocol analyses

Table 4 displays participants' characteristics at baseline, by the following groups: non-engaged (n = 249); engaged control (n = 125), and; engaged intervention, (n = 102). Negative and positive insulin appraisals did not differ between groups, while non-engaged participants more commonly reported being “not at all willing” to start insulin compared to those who engaged with their allocated resources (non-engaged: 20% vs. engaged control: 11%, and engaged intervention: 12%).

| Non-engaged control and intervention | Engaged control | Engaged intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 249 | n = 125 | n = 102 | |

| Gender: Women | 91 (37) | 50 (40) | 48 (47) |

| Age, years | 64 [56–69] | 66 [60–70] | 67 [58–71] |

| Education: University Degree | 186 (75) | 99 (79) | 83 (81) |

| Employment Status: Employed | 112 (45) | 38 (31) | 31 (30) |

| Language spoken at home: English | 233 (94) | 121 (97) | 96 (94) |

| Diabetes duration, years | 12 [5–18] | 13 [10–18] | 13 [11–18] |

| Diabetes complications: ≥1b | 112 (45) | 49 (39) | 37 (36) |

| Self-reported HbA1c in past 12 m | |||

| % | 7.4 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 1.3 | 7.0 ± 1.1 |

| Mmol/mol | 57.4 ± 16.6 | 56.0 ± 14.3 | 53.4 ± 12.1 |

| Glucose-lowering tablets per day | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] | 2 [1–3] |

| HCP discussion of insulin: Yes | 43 (17) | 14 (11) | 6 (6) |

| Insulin recommended previously: Yes | 7 (3) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Diabetes knowledge (DKT) | 63.7 ± 17.2 | 71.5 ± 16.4 | 74.0 ± 13.7 |

| Insulin-specific diabetes knowledge | 40.4 ± 16.6 | 40.8 ± 13.2 | 41.3 ± 12.9 |

| Negative insulin appraisals (ITAS) | 53.2 ± 9.1 | 52.7 ± 8.7 | 53.5 ± 10.0 |

| Positive insulin appraisals (ITAS) | 14.1 ± 2.1 | 14.5 ± 2.1 | 14.0 ± 2.2 |

| Hypothetical willingness to initiate insulin | |||

| Not at all willing | 49 (20) | 14 (11) | 12 (12) |

| Not very willing | 106 (42) | 69 (56) | 52 (51) |

| Moderately willing | 94 (38) | 42 (33) | 38 (37) |

| Diabetes Distress (PAID) | 29.7 ± 24.5 | 25.6 ± 22.7 | 24.6 ± 20.2 |

| Diabetes self-efficacy (CIDS-2) | 83.9 ± 9.7 | 82.9 ± 9.9 | 83.7 ± 9.2 |

- Note: Data are Mdn [IQR], mean ± SD, or n (%). ITAS: Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale, Negative subscale range = 16–80; Positive subscale range = 4–20; Insulin-specific diabetes knowledge, range = 0–100; PAID: Problem Areas in Diabetes, range = 0–100; CID-2: Confidence In Diabetes Self-care questionnaire for non-insulin-treated, range = 0–100. Higher scores indicate more of the concept assessed.

- a Engaged intervention: accessed ≥1 barrier page of the intervention website. Engaged control: self-reported access of the control resources at 2-week follow-up. Non-engaged: remaining participants across study arms.

- b Kidney disease, retinopathy, neuropathy, heart disease, stroke, vascular disease, sexual dysfunction.

At 2 weeks (but not 6 months), negative insulin appraisals were somewhat reduced in the engaged intervention group, but not in the engaged control group, relative to the non-engaged group (Mdiff [95% CI]: −2.7[−5.1 to −0.3]; Table 5). This effect may be clinically significant: the 95% confidence interval includes our minimal clinically important difference (4-points), but the confidence interval is wide, and the upper limit close to zero. Positive insulin appraisals were slightly increased at 2 weeks (but not 6 months) in both the engaged intervention (1.4 [0.8 to 2.0]) and engaged control (1.0 [0.4 to 1.6]) groups, relative to non-engaged group. These differences are unlikely to be clinically significant. A small increase in hypothetical willingness to start insulin was observed for both engaged groups compared to non-engaged participants at 2 weeks, not sustained at 6 months (Table S3).

| Outcome | Time point | Non-engaged control and intervention | Engaged control | Engaged intervention | Mean difference: Engaged control vs. Non-engaged (control and intervention) (95% CI) | Mean difference: Engaged Intervention vs. Non-engaged (control and intervention) (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 249 | N = 125 | N = 102 | |||||||

| n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean(95% CI) | ||||

| Negative insulin appraisals (ITAS) | Baseline | 248 | 53.1 (51.9, 54.3) | 125 | 53.1 (51.5, 54.6) | 102 | 53.4 (51.4, 55.4) | Ref | Ref |

| 2 weeks | 101 | 50.3 (48.8, 51.9) | 125 | 48.6 (46.8, 50.3) | 86 | 47.6 (45.8, 49.5) | −1.8 (−4.1, 0.6) | −2.7 (−5.1, −0.3) | |

| 6 months | 106 | 49.6 (48.1, 51.2) | 99 | 48.3 (46.6, 50.1) | 76 | 49.0 (46.6, 51.4) | −1.3 (−3.7, 1) | −0.6 (−3.5, 2.2) | |

| Positive insulin appraisals (ITAS) | Baseline | 248 | 14.2 (13.9, 14.5) | 125 | 14.5 (14.1, 14.9) | 102 | 14.0 (13.6, 14.5) | Ref | Ref |

| 2 weeks | 100 | 13.8 (13.4, 14.2) | 125 | 14.8 (14.3, 15.2) | 86 | 15.2 (14.8, 15.6) | 1 (0.4, 1.6) | 1.4 (0.8, 2) | |

| 6 months | 106 | 14.4 (14.0, 14.8) | 98 | 14.8 (14.4, 15.3) | 76 | 14.5 (14.0, 15.0) | 0.5 (−0.2, 1.1) | 0.1 (−0.6, 0.8) | |

- Note: ITAS: Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale, Negative subscale range = 16–80, Positive subscale range = 4–20. Higher scores indicate more of the concept assessed.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This RCT found no effect of ‘Is insulin right for me?’, relative to freely available online information, among Australian adults with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes who reported hesitancy about starting insulin. Rather, reductions in negative insulin appraisals, and a small increase in willingness to commence insulin, were observed across arms. However, limited protocol fulfilment was observed, and investigation of outcomes by engagement level suggests that ‘Is insulin right for me?’ may be effective among those who accessed it, that is, a modest reduction in negative insulin appraisals was observed at 2 weeks among those with minimum intervention engagement (relative to those with no engagement).

In contrast to the current study, the pilot RCT resulted in greater protocol fulfilment and intervention interaction: pilot participants were more likely to access their allocated web-based resource (80% vs. 59%) and visit all eight ‘barrier’ webpages (46%, vs. the current 21%).21 Further, preliminary evidence for a differential effect in negative insulin appraisals was also identified in the, albeit underpowered, pilot RCT. Viewed together, a maximum potential benefit (reflecting 95% confidence interval lower limit) of a 5–10 point reduction in Negative ITAS scores might be expected where engagement is observed. These results suggest that further process evaluation is warranted to explore study outcomes by exposure level (i.e., number of webpages viewed) or type (i.e., website content related to previously suggested effective clinical strategies).12-14 It was our intention for the resource to be brief and self-directed, enabling participants to tailor their use to personal needs (i.e., to engage only with content about their salient psychological barriers to insulin).20 Indeed, wide variation in level of intervention interaction was observed. However, the lack of prescribed website interaction (i.e., encouragement or requirement to access all eight web-pages) may have resulted in lower engagement overall. It remains to be tested whether prescribing engagement with the entire intervention increases its effectiveness or its perceived burden.

Alternatively, the contrasting protocol fulfilment and evidence may be a consequence of differing recruitment strategies (online promotion vs. direct invitation via national diabetes registry) and qualitatively different participant groups. Compared to the current study, pilot participants reported similar demographics, clinical characteristics, and average negative ITAS scores. However, in the pilot, somewhat greater diabetes knowledge, willingness to commence insulin, and prior discussion of insulin with health professionals was observed, suggesting greater receptiveness to the intervention.21 Similarly, relative to the ‘non-engaged’ group, participants meeting minimum engagement criteria in the current study reported somewhat greater diabetes knowledge and were less likely to report being ‘not at all willing’ to start insulin at baseline. Thus, those most likely to benefit may have been least likely to participate, and most likely to disengage following enrolment, a phenomenon also observed elsewhere.16-18 However, negative insulin appraisal scores were comparable between engagement levels and with other Australian samples,9, 21, 29 and baseline scores suggest the potential for demonstrating intervention benefit (i.e., ceiling effects were not observed). Regardless, results indicate a need to explore potential reasons for the low engagement with opportunity for further intervention refinement. Planned review of free-text user feedback responses may provide such insights (among completers).

It is important to note that this self-directed, low-intensity intervention was evaluated in a non-clinical setting by participants for whom insulin was not clinically indicated. Indeed, it may be more suitable (in terms of acceptability, engagement and effectiveness) if people with type 2 diabetes were referred to the intervention by their health professional at the point when insulin is first raised as a possible treatment option; or among those for whom insulin is clinically indicated as a therapeutic option for those who are delaying insulin uptake and expressing psychological barriers. Further data exploration to understand for whom the intervention worked could facilitate more appropriate implementation. Previously, health professionals involved in the intervention development and/or refinement indicated their enthusiasm for the resource,20 and the online format is likely implementable within clinical care. However, further stakeholder testing and piloting within a clinical setting would be prudent prior to conducting a full RCT.

In addition to low protocol fulfilment, study limitations include recruitment of a self-selected sample who are not fully representative of the Australian type 2 diabetes population (i.e. a high proportion were university educated; there was limited linguistic diversity). However, the current study was an appropriate and important step in intervention testing, conducted in the setting in which we proposed implementation (i.e., promoted and made available online via national diabetes bodies; independent of, but potentially supplementary to clinical care) and completed by a real-world sample, which may be representative of those most likely to access the resource online. Additional strengths of the current study include the comprehensive assessment of psychosocial outcomes using validated assessment tools and objective intervention website analytics data collection providing opportunity for secondary analysis. Furthermore, this study provides novel evidence for existing online insulin-specific information in Australia. Though, in contrast to the intervention, no objective data were collected for the control group regarding resource interaction, reducing opportunities for further comparative assessment of resource engagement and effect.

In this RCT, there was no evidence of a beneficial effect of the intervention, ‘Is insulin right for me?’, over existing online resources, in addressing psychological barriers to insulin use among Australians with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes. However, the PP analysis and the prior pilot RCT findings suggest there is potential to increase the impact of the intervention on attitudes to insulin by increasing engagement. These findings warrant further research to examine the optimal intervention dose–response; to identify for whom the intervention may be most acceptable, engaging and effective; and to examine its impact when used in a clinical setting, among participants for whom insulin is clinically indicated.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elizabeth Holmes-Truscott and Jane Speight conceived, and Edith E. Holloway project managed, the research programme. Edith E. Holloway, Jane Speight, Timothy Skinner and Elizabeth Holmes-Truscott led, and John Furler and Virginia Hagger contributed to the development of the website intervention. All authors contributed to study design. Edith E. Holloway and Shaira Baptista undertook data collection. Benjamin Lam cleaned and analysed data and prepared tables. Elizabeth Holmes-Truscott prepared the first and subsequent drafts of this manuscript, following critical review by all co-authors. All authors reviewed and approved submission of the final manuscript. Elizabeth Holmes-Truscott takes responsibility for the contents of the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the adults with type 2 diabetes who participated. Participants in the study were recruited (in part) as people with diabetes registered with the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS.) The NDSS is an initiative of the Australian Government administered by Diabetes Australia. We thank Victoria Yutronich (Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes; ACBRD) for website design and technical support, Hanafi M Husin (ACBRD) and Sharmala Thuraisingam (ACBRD) for statistical support, and Jasmine Schipp (ACBRD) for research assistance. Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley - Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This investigator-sponsored study was supported by funding from Sanofi, Australia. Sanofi was not involved in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation or reporting of the study, but was given the opportunity to review the manuscript prior to submission. The decision to submit for publication was made independently by the authors. Sanofi will be allowed access to all de-identified data from the study for research and audit purposes, if requested. In-kind support including project oversight was provided by the Investigator team. EHT and JS are supported by the core funding to the Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes (ACBRD) provided by the collaboration between Diabetes Victoria and Deakin University. EEH, SB and BL were supported, in part, by an unrestricted grant from Diabetes Australia. Costs associated with participation incentives, website development and data management were funded (fully or partially) by the ACBRD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

EHT has undertaken research funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Diabetes Care, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi, Australia; the ACBRD has received speaker fees from Novo Nordisk and Roche; and has served on an advisory board for AstraZeneca. JF has received unrestricted educational grants for research support from Roche, Sanofi, and Medtronic. TS serves on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and Liva Health Care, and is currently on an EIT Health research grant held jointly with Roche Diagnostics. JS has served on advisory boards for Janssen, Medtronic, Roche Diabetes Care, and Sanofi Diabetes; her research group (the ACBRD) has received honoraria for this advisory board participation and has also received unrestricted educational grants and in-kind support from Abbott Diabetes Care, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Roche Diabetes Care, and Sanofi. JS has also received sponsorship to attend educational meetings from Medtronic, Roche Diabetes Care, and Sanofi Diabetes, and consultancy income or speaker fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diabetes Care, and Sanofi Diabetes. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.