Physical therapy in children with cerebral palsy in Brazil: a scoping review

Abstract

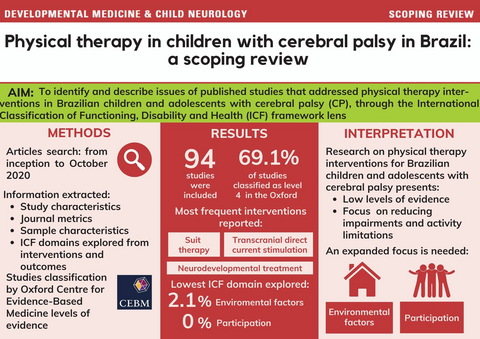

Aim

To identify and assess published studies concerning physical therapy in Brazilian children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (CP) using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework.

Method

Articles in English and Portuguese published until October 2020, with no date restrictions, were searched in several different databases. Study characteristics, journal metrics, sample characteristics, and ICF domains explored intervention components and outcomes were extracted. Studies were classified according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine hierarchy levels to characterize the evidence.

Results

Ninety-four studies were included. Spastic CP with fewer limitations in gross motor abilities was the most reported; 67% of the studies had low levels of evidence and were published in journals without an impact factor. The three most frequent interventions were neurodevelopmental treatment, suit therapy, and transcranial direct current stimulation. Intervention components explored body functions and structures (73.4%), activity (59.6%), environment (2.1%). They did not explore participation (0%). The outcomes investigated addressed activity (79.8%), body functions and structures (67.0%), and participation (1.1%), but not environment (0%).

Interpretation

Studies of physical therapy for Brazilian children and adolescents with CP focused on reducing impairments and activity limitations. Studies with higher levels of evidence and an expanded focus on participation and environmental factors are necessary.

Graphical Abstract

This scoping review identifies and describes studies on physical therapy in Brazilian children and adolescents with cerebral palsy through the lens of the ICF framework.

This scoping review is commented by Alcântara de Torre on page 531 of this issue.

Portuguese translation of this scoping review is available in the online issue.

Abbreviations

-

- ICF

-

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

-

- LMIC

-

- Low- and middle-income countries

-

- NDT

-

- Neurodevelopmental therapy

-

- OCEBM

-

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

What this paper adds

- Studies focused on reducing impairments and activity limitations.

- Participation and environmental factors were addressed only minimally.

- Many physical therapy studies presented low levels of evidence.

- Most studies were published in journals without an impact factor.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as a group of developmental disorders of movement and posture attributed to a non-progressive injury occurring in the immature brain.1, 2 It is one of the most common causes of physical disability in childhood, with a prevalence of 2.1 cases per 1000 live births in high-income countries. In low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), CP prevalence may be even higher.3-5 Additionally, LMIC may have a higher percentage of individuals with more severe limitations.6-8

At the beginning of the 21st century, with the creation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)9-11 framework, the World Health Organization proposed significant changes (expansions) to the rationale and language of health and disability. Thereafter, physical therapists and other professionals started to apply the ICF framework in health promotion, prevention, intervention strategies, and to develop the direction of relevant studies. The framework highlighted the importance of focusing on the activity, participation, and contextual aspects of people’s lives, beyond just offering therapies aimed at ‘fixing’ impairments in body functions and structures.10, 12-14

Historically, physical therapy interventions in children and adolescents with CP mainly focused on repairing impairments (at the ICF level of body functions and structures).15 After implementation of the ICF and research advances in the past decade, several therapy interventions, such as goal-directed training, treadmill training, home programs, constraint-induced movement therapy, environmental enrichment, and task-specific training have been investigated.13, 16 These modalities have been shown to be effective primarily on motor outcomes and are mostly related to the activity domain.16 To date, little is known about the effectiveness of physical therapy on participation.17, 18

Most of the available literature supporting interventions for children and adolescents with CP originates from research in high-income countries (e.g. USA, UK, Canada, and Australia).19 Due to the lack of financial resources and other public health issues, the contribution of LMIC (e.g. African countries, India, and Brazil) to the body of evidence regarding CP is much lower.5, 19 Furthermore, a high proportion of children with CP from LMIC (e.g. Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia, and Ghana) have no access to any form of intervention before the age of 3 years.20, 21 Although elements of the ICF model are often addressed in research on CP in high-income countries (such as participation and environmental factors),22, 23 the extent to which this model has been implemented in LMIC research and practice is still uncertain.5

Some studies have investigated the scope of the LMIC literature on physical therapy for CP. In India and some African countries, the body of research does not follow the current worldwide state of evidence.5, 19 Interventional studies in these LMIC are mainly concerned with body functions and structures, with much less attention paid to activity and participation.5, 19 In addition, a significant percentage of these studies were published in low-quality journals.19 To date, there is no information addressing the scope of the literature regarding CP in other LMIC, such as Brazil.

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world, with >200 000 physiotherapists.24, 25 Brazil is also considered one of the top 25 most productive countries in CP research and one of the most productive LMIC in this list.26 In Brazil, several physical therapists work with individuals with CP. Child and adolescent neurofunctional physiotherapy is a well-established specialization in the country and the number of research programs in the rehabilitation field has been increasing in the past years.27, 28 In this context, understanding the nature of the Brazilian research literature may help Brazilian researchers to improve their approach and how they deliver updated information on physical therapy to the pediatric community. The aim of this scoping review was to identify published studies that addressed physical therapy in Brazilian children and adolescents with CP as mediated by the ICF framework.

METHOD

This scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. It was conducted using the following steps: (1) identify the purpose of the review; (2) identify and select potential studies; (3) extract and plot data; and (4) order, synthesize, and report the results.29 The review protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework Register (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7QFHG).

Identifying the purpose of the review

This scoping review aimed to (1) review the characteristics of the literature on physical therapy in Brazilian children and adolescents (up to 20y) with CP, including the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM)30 levels of evidence and (2) categorize the components of the interventions and outcomes according to the ICF framework.

Search strategy and search terms

Searches for eligible studies were conducted in Medline/PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus, CINAHL, Web of Science, PEDro, and Lilacs. Gray literature was searched using Google and Google Scholar. The descriptors used were ‘cerebral palsy’, ‘rehabilitation’, ‘physical therapy’, ‘physical therapists’, ‘children’, ‘adolescent’, ‘Brazil’, and ‘clinical trials’ in both English and Portuguese (in Latin American databases). A detailed list of descriptors and search strategy for each database is provided in Table S1 (online supporting information). We manually searched all identified studies for possible additional eligible studies. The search strategy (without date restrictions) was conducted in October 2020 and researchers were assisted by a librarian.

Study selection

This scoping review included n-of-1 trials, randomized trials, non-randomized control trials, case studies, case series/case reports, single-subject designs, and historically controlled studies that investigated physical therapy in Brazilian children and adolescents with CP. Full-text articles published in English, Portuguese, or both were included. As an eligibility criterion, studies were included when they reported interventions related to the scope of physical therapy. The definition of physical therapy followed the normative laws of the Conselho Federal de Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional (Brazilian Council of Physical and Occupational Therapy).31 As per the regulations of the Brazilian Council of Physical and Occupational Therapy, intervention studies that were not exclusive to physical therapists (e.g. hand–arm bimanual therapy, constraint-induced movement therapy, sensory integration, hippotherapy, and educational programs) were included if they were led by physical therapists. Interventions exclusively related to the scope of other areas (e.g. botulinum neurotoxin A and orthopedic surgery) were not included, except when combined with physical therapy. Studies that did not clearly report outcomes were also excluded.

Screening

A screening process was conducted independently by two reviewers (MASF and ISC), first identifying titles and abstracts, and then evaluating potential full-text articles using our eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (HRL). To ensure reliability and consistency during the screening process, eligibility criteria were tested by examiners in the first 10 titles and abstracts in the databases.

Data extraction

The research team developed a data extraction form and tested it in the first five studies to determine its consistency with the purpose of the study. Data extraction included: (1) study characteristics (i.e. authors, year of publication, title, language of publication, study type, study aims, OCEBM levels of evidence, proponent institution, Brazilian regions, and access links); (2) journal metrics (i.e. journal title, impact factor, and indexing location); (3) sample characteristics (i.e. sample size, age, clinical CP type, Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS] levels); and (4) intervention and outcomes (i.e. main intervention – characteristics, frequency, and intensity – and ICF domain[s] explored; outcomes – ICF domains assessed and tools/scales). All data extraction was performed by the first author (MASF) and reviewed by the second author (KMAA). Study design was classified by the second author (KMAA) and verified by the fifth author (ACRC). To identify the institution the study originated from, we considered the information in the study’s ethics approval register or the affiliation of the first and/or last author of the study.

Categorization

Journal metrics

Details about the journal impact factor for the studies selected were extracted by manual search of the Journal Citation Reports (Web of Science) website as an indicator of quality.32, 33 For journals without an impact factor, no value was reported.

Level of evidence

All studies selected were classified according to the OCEBM levels of evidence for intervention studies.30 The OCEBM hierarchy consists of five levels of evidence, ranging from level 1 (strongest) to level 5 (weakest), as follows: level 1, systematic reviews/meta-analyses that critically summarize several studies, and n-of-1 trials; level 2, randomized controlled trials; level 3, studies such as non-randomized studies that do not have strong control of bias; level 4, studies where a relatively low level of evidence is present, primarily including descriptive studies, such as case series/case reports; and level 5, studies based on mechanistic reasoning, whereby evidence-based decisions are founded on logical connections, including a pathophysiological rationale. The criteria used for the study design definition are reported in Table S2 (online supporting information).34, 35

Intervention characteristics

The main intervention components (i.e. experimental group) were categorized with regard to their principles, active components, and mechanisms (as extracted from the study) into: (1) body function and structure interventions (i.e. interventions that primarily manipulate body functions or body structures, such as strength training, stretching, or mobility/stability of joint interventions); (2) activity interventions (i.e. interventions promoting task training aspects, such as task-specific training or gait training); (3) participation interventions (i.e. interventions promoting frequency and involvement in real-life contexts, such as community-based treatments); or (4) environmental factor interventions (i.e. interventions that provide modifications of environmental aspects, such as context-focused therapy and conductive education for parents).11 Since the ICF framework makes no clear distinctions between activity and participation domains, the principles of participation-based interventions (i.e. goal-oriented, family-centered, collaborative, strength-based, ecological, and self-determined)18 were considered. Additionally, to better categorize interventions as ‘environmental factors’, the principles of contextual therapies (e.g. with a focus on identifying the constraints and facilitators related to task and environment)36 were also considered.

All outcome measures investigated were classified into ICF domains and followed the definitions set out in the ICF, according to the standardized instruments used. Activity outcome measures were categorized using the qualifier capacity (i.e. what a person can do in a standardized environment) and performance (i.e. what a person actually does in their usual environment).11 Outcome measures were categorized as a ‘participation’ domain if they covered its constructs, with instruments assessing attendance or involvement in life situations.17 Studies reporting non-ICF outcome domains were extracted and reported (e.g. quality of life). For those studies that examined the additional effect of physical therapy on other intervention modalities (e.g. botulinum neurotoxin A), we only categorized the physical therapy intervention (e.g. physical therapy treatment after botulinum neurotoxin A). All these categorizations were performed by the first author (MASF) and verified by the second (KMAA), with conflicts resolved by consensus between authors.

RESULTS

The database searches identified 6677 studies; after screening the title and abstract, 689 full-text studies were evaluated under our eligibility criteria. After review, 595 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, 94 studies were retained for data extraction (Fig. S1, online supporting information).

Table 1 reports the main characteristics of the studies included in this scoping review (see also Table S3, online supporting information). Between 1996 and 2020, the 94 studies37-130 were published in 46 different journals, 67% of them without an impact factor and 33% with an impact factor from 1.0 to 4.4. The studies included a total of 1138 children and adolescents with CP, aged from 1 to 18 years, with bilateral (51.3%) or unilateral (31.9%) spastic, dyskinetic (4.4%), and ataxic (2.7%) CP subtypes, classified in GMFCS levels I (21.5%), II (26.0%), III (18.1%), IV (9.0%), and V (7.9%). Several studies did not report the CP subtype and GMFCS level (9.7% and 17.5% respectively).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Publication decade | |

| 1996–2000 | 1 (1.1) |

| 2001–2010 | 22 (23.4) |

| 2011–2020 | 71 (75.5) |

| Brazilian regions | |

| North | 0 (0) |

| North-west | 7 (7.4) |

| Midwest | 4 (4.3) |

| South-east | 58 (61.7) |

| South | 25 (26.6) |

| Main proponent institution | |

| Public universities | 47 (50.0) |

| Private universities | 46 (48.9) |

| Rehabilitation centers | 1 (1.1) |

| Language | |

| English | 39 (41.5) |

| Brazilian Portuguese | 49 (52.1) |

| Both | 6 (6.4) |

| OCEMB level of evidence | |

| Level 1 | 0 (0) |

| Level 2 | 19 (20.21) |

| Level 3 | 10 (10.6) |

| Level 4 | 65 (69.1) |

| Level 5 | 0 (0) |

| Indexed databases | |

| PubMed | 36 (32.4) |

| Lilacs | 22 (19.8) |

| Scielo | 17 (15.3) |

| Google, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus, manually searched, PEDro | 36 (32.5) |

- OCEMB, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

The levels of evidence of the selected studies varied from 2 (20.21%) to 4 (69.1%) (Table 1). In total, 24 different interventions were investigated in the studies. Table 2 shows the 10 most frequently investigated interventions and the corresponding OCEBM levels of evidence. The other 14 interventions investigated were: task-specific training; fitness training; stretching; vegetable oil; Kinesio Taping; motor imagery training; constraint-induced movement therapy; hand–arm bimanual intensive therapy; proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation; conductive education for parents; respiratory physical therapy; riding simulator; goal-directed training; and conventional physiotherapy.

| Interventiona | Number of studies | n (%) of studies in each OCEMB level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | ||

| Suit therapy | 12 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (100) |

| NDT | 10 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) |

| TDCS | 10 | 8 (80) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) |

| Hydrotherapy | 9 | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (66.7) |

| Virtual reality | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (87.5) |

| Treadmill training | 7 | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (71.4) |

| Strength training | 7 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) |

| Electrical stimulation | 7 | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) |

| Assistive technologyb | 6 | 3 (50) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Hippotherapy | 5 | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 3 (60) |

- a Only therapies cited more than four times in the studies included in the scoping review are described in this table.

- b Includes orthoses, walker, and insole. OCEMB, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; NDT, neurodevelopmental treatment; TDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Table 3 shows the ICF domains explored across interventions and outcomes measures. The body function and structure domains were the most explored in the interventions (73.4%). The most explored outcome measures focused on the activity domain (79.8%) and the most widely used instrument was the Gross Motor Function Measure, which assesses the capacity for activity. Two studies explored environmental factors in their interventions and only one study explored the participation domain as an outcome (Table S3). Additionally, three studies investigated quality of life as an outcome.

| ICF domain |

Intervention n=94, n (%) |

Outcome measure n=94, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Body functions and structures | 69 (73.4) | 63 (67.0) |

| Activity | 56 (59.6) | 75 (79.8) |

| Capacity | – | 72 (76.6) |

| Performance | – | 12 (12.8) |

| Participation | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Environmental factors | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

| Non-ICF domain | ||

| Quality of life | – | 3 (3.2) |

- ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; –, not applicable.

DISCUSSION

Using the ICF framework, this study aimed to identify several aspects of the literature addressing physical therapy available to Brazilian children and adolescents with CP. The amount of research produced in Brazil has increased exponentially in the last decade; however, most studies have been published in poor-quality journals and have low levels of evidence. The focus of the reported intervention studies was to modify impairments in children with spastic CP, aiming for fewer limitations in gross motor abilities.

In the last decade, the number of studies addressing individuals with CP has grown exponentially.26 According to current evidence, the therapy components with the greatest potential to promote benefits in individuals with CP include goal-directed practice of real-life tasks, child self-initiated active movements, high-intensity therapy, participation, and family engagement in therapeutic planning.131, 132 In contrast, this scoping review showed that in Brazil, the most studied interventions, such as suit therapy, neurodevelopmental therapy (NDT), and transcranial direct current stimulation do not necessarily address all these components.133, 134

NDT is the best known and implemented intervention in several countries, including Brazil,135 where it is widely taught in training courses. Despite its name, identifying the original approach is no longer possible.136 Primarily, NDT focuses on reducing neuromotor impairments, with techniques aimed at modifying body functions and structures (e.g. to normalize tone or inhibit reflex). Indeed, all studies that reported NDT as identified in this scoping review pointed out these original passive characteristics but also described other elements related to the activity domain, such as mobility and self-care training. Despite the changes in NDT observed over time, it is difficult to say if this approach has shifted from looking solely at ‘fixing’ neuromotor impairments to addressing the ICF activity domain consistently. Furthermore, the NDT studies included in this scoping review did not present participation as an investigated outcome.

Suit therapy interventions are relatively new and have gained popularity in Brazil, possibly due to good financial returns. In the suit therapy studies included in this scoping review, the intervention elements and outcomes explored both body functions and structures (e.g. strengthening) and activity (e.g. mobility tasks). The high frequency identified in this scoping review is in line with the most common therapy delivery by pediatric physiotherapists in Brazil.137, 138 These interventions created great expectations for child improvement and a significant family commitment to obtaining resources to allow children access to this type of intervention; this generated concern from Brazilian physical therapy associations.139-141 Despite the popularity of suit therapy in Brazil, the main ICF intervention element and outcome target of this therapy are not well established in the literature.133, 134

Transcranial direct current stimulation is a new and more expensive approach to therapy and was the third most frequent intervention identified in this scoping review. Its mechanism of action is based on electrical stimulation of the brain, through the cranium, and is aimed at improving neuromusculoskeletal body functions and structures, as well as activity (such as capacity and performance); all interventions and outcomes extracted from the studies are included in this scoping review. However, no information as to whether transcranial direct current stimulation results might be transferred to participation outcomes was identified.142 All transcranial direct current stimulation studies included in this scoping review were carried out by the same research group, leading to potential publication bias and thus decreasing the strength of the evidence.143 Therefore, the results of this scoping review indicate the need to expand research on this therapy to improve the quality of the evidence and support any decisions on its use in clinical practice.143

Among the remaining 10 most frequent interventions extracted from the studies, we observed a focus on body functions and structures (hydrotherapy, strength training, electrical stimulation, and assistive technology [e.g. orthoses]), and an activity component targeting mainly mobility training (virtual reality, treadmill training, and hippotherapy). These approaches are well known to Brazilian physical therapists; traditionally, they are carried out in clinics or rehabilitation centers, without modifying the environment where the child is living. Furthermore, these studies did not assess the carryover benefits of these interventions on participation outcomes.133, 144

Overall, the interventions extracted from the studies included in this scoping review primarily showed a focus on ‘body functions and structures’, followed by ‘activity’. Less attention was paid to ‘participation’ and ‘environmental factors’. Our results are in accordance with other studies carried out in other LMIC.5-7 Studies investigating rehabilitation approaches in children with CP in India and Africa showed a substantial focus on interventions that reduce impairments, with minimal attention paid to ‘activities and participation’ and ‘environmental’ and ‘personal factors’.13, 15-17 Despite studies conducted in Western countries focusing more on ‘activity and participation’ and ‘contextual factors’, their translation to clinical practice is a challenge.13 Considering this scenario, it is important to highlight that interventions aimed at remediating ‘body functions and structures’ would not automatically translate into improved activity or participation without addressing these specific domains and the real-life contexts of families.13-15 Nowadays, interventions that consider activity (e.g. active goals set by the child or caregiver and task-specific practice in real-life situations), participation (e.g. mutually agreed upon family and professional goals for home and community participation), and contextual factors (e.g. emphasis on changing the task and environment rather than the child) are deemed key elements for functioning in individuals with CP, which is consistent with current approaches and evidence.13-15, 145 Assuming that the most investigated interventions are popular in Brazil’s clinical practice, these results reinforce the need to expand the main focus of therapists to follow the current state-of-the-art physical therapy interventions for children and adolescents with CP.5, 13, 19

Regarding participant characteristics in the studies included in this scoping review, children with spastic CP in GMFCS levels I to III were recruited most frequently. These children could walk independently or with the aid of gait devices in most environments.146 Given the lack of robust epidemiological studies on CP in Brazil, it is not possible to assume that this clinical type and functional level are the most prevalent in this country. The higher frequency of the recruited subgroup of children with CP may be due to the lack of well-established protocols and evidence of physical therapy interventions in individuals with more limited motor functions (GMFCS levels IV and V).8, 14 An ongoing national multi-center study, the PartiCipa Brazil Research Project, will determine the most frequent clinical types and functional levels of Brazilian individuals with CP, which may guide future interventional studies to target the country’s most prevalent CP profile.147

Most of the studies included in this scoping review were classified at level 4 in the OCEBM system, which ranges from levels 1 to 5 (strongest to weakest).30 The OCEBM levels of evidence used in this scoping review represent the expected rigor in study design and control of bias, thereby indicating a certain level of confidence that may be placed in their findings.148 Studies at the top represent stronger evidence; those at the bottom represent weak evidence. Studies at the top, such as randomized controlled studies, are the criterion standard and provide the most reliable evidence on the effectiveness of interventions because of the processes used when conducting these studies (e.g. eligibility criteria, individuals randomly allocated to groups, concealed allocation, and blinding).149 Furthermore, a significant number of Brazilian studies (67%) were published in journals without an impact factor (based on the Journal Citation Reports resource). An impact factor is an indicator of quality control and selectivity (e.g. journals are monitored and excluded from the Journal Citation Reports when they demonstrate predatory behavior).32, 33 Results of studies from journals without an impact factor and showing weak levels of evidence are not trustworthy for clinical decision-making; their findings need to be interpreted with caution.33, 150 Thus, well-designed Brazilian interventional studies might facilitate evidence-based practice and reduce the gap between the research and clinical fields.

Furthermore, interventional studies on CP published in Brazil are mostly conducted in universities, with 88.3% in the two most economically developed regions (south and south-west). The northern region of Brazil, the area with the lowest income concentration, was not represented in any of the studies, meaning that there is no evidence of interventions aimed at children with specific environmental characteristics in this region. Lack of research funding and the small number of higher education programs and research groups can be challenging for research projects in the north, north-east, and midwest regions of Brazil.151-153 Considering the inequality between Brazilian regions, future efforts are needed to support and promote high-quality research in less-developed regions. Supporting clinical/rehabilitation settings in partnership with universities for high-quality research (especially on the participation domain and environmental factors) is very important since they usually have the adequate infrastructure to recruit a large number of participants who can count on free public transportation and are generally close to the research facilities.154 Furthermore, Brazil has recently faced a significant reduction in its science budget,155, 156 thereby supporting the need to stop the scarce resources available in low-quality research that addresses interventions shown to have limited effects.

Considering the country’s significant social discrepancies, and that over 80% of its population depends on its public health service, it is important that Brazilian researchers invest their efforts in inexpensive and easy-to-reproduce interventions in Brazilian clinical practice. Interventions such as home programs, environmental enrichment, and task-specific training are inexpensive, equipment-independent, directed to family goals, and carried out in the child’s natural environment; this corresponds to the current trend of interventions aimed at improving performance and no longer aiming at only correcting impairments.157, 158 Future studies should investigate the effects of these high-level, inexpensive, evidence-informed interventions in the Brazilian context. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, new opportunities to deliver low-cost rehabilitation services in natural environments have become a reality.159, 160

This scoping review has some limitations. First, articles from databases including Brazilian journals or those published in other languages may have been missed. Second, although we did not engage in a detailed critical appraisal of all methodological aspects, challenges such as non-standardized therapy terms, lack of description of the intervention component, and study design not clearly reported might have led to a misleading outcome and components of the classification of the intervention. Third, terms related to the environment were missing from the search strategy, which may have influenced the low number of studies included. Fourth, with the aim of providing relevant aspects for Brazilian physical therapy clinical practice, studies investigating interventions common to other professionals (e.g. constraint-induced movement therapy) but not led by a physical therapist were excluded from this review. We recognize that it is still important to shed light on these interventions through the ICF framework. Fifth, our inclusion criteria did not exclude papers published before the inception of the ICF framework.11 Despite this, only one article included in the present scoping review was published before 2001; this lessened our limitation when reporting study interventions and outcomes in light of the ICF framework. Sixth, we used the OCEBM system to classify levels of evidence. The OCEBM levels of evidence were used to find the likely best evidence but are not intended to provide a definitive judgment about its quality and recommendations.30 Despite these limitations, the purpose of rating studies using this system in this scoping review was to provide clinicians and researches with a general view of the best evidence, which could be used to (1) inform clinicians as to how trustworthy studies including Brazilian children and adolescents with CP are and (2) provide a rapid comprehensive resource that could be used by researchers to help prioritize efforts and funding in the future to improve the methodological quality of studies. Bearing in mind that a definitive recommendation is not possible from our scoping review, further studies aimed at better investigating this topic are needed.

CONCLUSION

This review showed that the amount of research on children and adolescents with CP in Brazil is constantly increasing. The most studied interventions presented low-quality evidence, which means that the evidence reported is not trustworthy for clinical decision-making. The focus of the studies was on reducing impairments and activity limitations, with minimal attention paid to participation and environmental factors and the evaluated outcomes. Brazilian researchers must expand their focus on therapeutics to include contextual and participation factors, thus promoting a more comprehensive view of individuals with CP. Well-designed Brazilian intervention studies might facilitate evidence-based practice and reduce the gap between the research and clinical fields. Many strategies could be considered, such as partnerships between junior and senior researchers and research centers, financial investment, and support by university librarians who can educate professionals about predatory journals and the writing process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the contribution and participation of all authors in the stages of this work, including conceptual development, draft preparation and approval of the final version, and funding through PPSUS MS/CNPQ/FAPEMIG/SES (grant no. APQ-00754-20 to HRL). The authors have stated they had no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated.