Concepts of functioning and health important to children with an obstetric brachial plexus injury: a qualitative study using focus groups

Abstract

Aims

The aims of this study were to explore and understand the perspectives of children with an obstetric brachial plexus injury (OBPI) regarding functioning and health, and to create an overview of problems and difficulties that patients encounter in daily life.

Method

We conducted a focus group study with 48 children (25 male, 23 female), aged 8 to 18 years, with an OBPI. Eleven open-ended questions regarding problems or difficulties in daily life were asked in group sessions with 4 to 7 children within the same age range. These group sessions were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All problems and difficulties mentioned in each focus group were linked to corresponding categories of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health – Children & Youth Version (ICF-CY).

Results

Eight focus groups were conducted. A total of 143 unique ICF-CY categories were identified. Of these categories, 61 (43%) were related to the ICF-CY component ‘activities and participation’, 31 (22%) were related to ‘body functions’, 29 (20%) were related to ‘environmental factors’, and 22 (15%) were related to ‘body structures’.

Interpretation

This study shows that children with OBPI experience difficulties in all areas of functioning, as well as in both environmental and personal factors.

Abbreviations

-

- ICF

-

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

-

- ICF-CY

-

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health – Children & Youth Version

-

- OBPI

-

- Obstetric brachial plexus injury

What this paper adds

- This study demonstrates the perspectives of children with an OBPI regarding functioning and health.

- The study provides a list of specific problems and limitations in both daily activities and societal participation that are relevant for this population.

Obstetric brachial plexus injuries (OBPIs) are the result of a traction injury during delivery. The incidence of OBPI varies from 0.4 to 5.1 per 1000 live births in various countries.1, 2 The majority of OBPIs are mild, and about 70% of affected infants will experience spontaneous functional recovery between 4 months and 6 months of age.3, 4 The remaining 30% are left with functional deficits5 depending on the severity of the injury (axonotmesis, neurotmesis, avulsion) and on which roots are involved (C5–T1).

Most studies of the outcomes of OBPI carried out to date have focused on the functional outcome of the affected limb in terms of range of motion, pattern of movement, or muscle strength; however, less attention has been paid to the effects on the everyday life of the child and (later) the adult.6, 7 Over the past 10 years a limited number of studies of the impact of OBPI on ‘activities and participation’ category of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Children & Youth Version (ICF-CY), have been published. Studies using the Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument8 have found that scores for mobility and sports/physical functioning are lower in children with OBPIs than the population norms.9-12 Ho et al.13 found that children with OBPI and hand impairment had more difficulties with self-care activities than individuals without hand impairment.13 Bellew et al.4 by analysing interpersonal relationships, found that more severe injury was associated with poorer developmental and behavioural outcome. Yang et al.14 found that only 17% of children with a right OBPI prefer the right upper limb for certain activities in daily life (fine and gross task movements), in contrast to 90% of individuals in the general population.14 Two studies gave detailed information on the participation and ability of individuals in daily and leisure activities.15, 16 One study found that children with an OBPI might experience difficulties with writing.15 The other study showed that adolescents with OBPI had interests, activities, and a social life very similar to those of their peers. Differences, however, were found in self-esteem in performing sport/motor activities, with self-esteem being significantly lower in adolescents with the most severe type of OBPI.16

Although these studies show limitations in activities and participation in children with an OBPI, they each tend to focus on only one or two aspects of functioning. Furthermore, in only 3 of the 11 studies were data obtained from the perspective of the children themselves;15-17 in most studies, the perspective of the caregiver was employed. Thus, so far, little is known on the perspective of children with OBPI on different levels of functioning, in particular the level of activities and participation. All aspects of health status, however, should be taken into account to better understand, evaluate, and measure people's daily experiences, limitations, and resources. With the exploration of the impact of a condition on people's lives, it is important to include not only the professional's point of view, but also the patient's perspective. Personal values and personal importance of several aspects of functioning vary between individuals, as well as between patients and health professionals.18, 19

To identify relevant areas of functioning and to describe the burden of OBPI from the patients' perspective, the ICF-CY offers a helpful framework. The ICF-CY is a worldwide-accepted model providing a universal language for the description of functioning and disabilities in children and adolescents. It includes the components ‘body structures’, ‘body functions’, ‘activities and participation’, and ‘environmental factors’.20 The ICF-CY was derived from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in 2007.21 As little is known of the perspective of children with an OBPI regarding the impact of their condition on their functioning in terms of activities and participation and contextual factors, the aim of this study was to explore and understand the perspective of individuals (8–18y old) with OBPI. For this purpose focus groups were employed, as these are a form of qualitative research which can help to understand the experiences of patients.22

Method

Study design

A focus group is a carefully planned series of discussions designed to obtain perceptions about quality of life in a permissive, non-threatening environment.22 The non-directive nature of focus groups offers participants an opportunity to comment, to explain, to disagree, and to share experiences and attitudes.22 A topic guide, based on the ICF, with open-ended questions was used to structure the discussion in the focus groups. Focus groups were formed by age group (i.e. 8–9y, 10–12y, 12–13y, 13–14y, and 14–17y). The study was conducted in 2011 and 2012 at the Leiden University Medical Center. Patients who were willing to participate had to give written and oral informed consent (for individuals under 12y of age, parents were asked for their consent; for patients between 12y and 17y of age, both the individual and the parents were asked for their consent) according to the Declaration of Helsinki 1996. Patients were invited to attend one focus group session at the Leiden University Medical Center. Patients received a small gift and reimbursement of travel expenses for their participation in this study.

Participants

A purposive sampling technique was used to identify potential participants from the outpatient multidisciplinary nerve surgery unit of the Leiden University Medical Center. Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they (1) were diagnosed with an OBPI; (2) were treated by a neurosurgeon, orthopaedic surgeon, or rehabilitation specialist at our centre; (3) were fluent in Dutch; and (4) were between the ages of 8 years and 18 years.

Exclusion criteria included (1) concomitant neurological or musculoskeletal disorders; (2) concomitant congenital upper limb differences; (3) bilateral upper extremity involvement; (4) the presence of any concurrent medical or psychiatric condition that, in the investigator's opinion, could prelude participation in this study; or (5) a cognitive or other impairment that would interfere with participation in a group discussion.

Selection of participants was based on the clinical diagnosis of OBPI and a maximum distance of 150km from their home to our centre, to minimize the burden of participation. When recruiting participants, the aim was to have a minimum of four participants per age group. As the number of eligible patients was limited, previous surgical or conservative treatment or type of lesion were not taken into account in the selection process.24 Patients who met the inclusion criteria were first informed about the study design and purpose of the study by telephone by the study coordinator (CS) and, subsequently, by means of a written information leaflet. Sex, age, type of lesion, side of affected limb, and history of a primary and/or secondary operation were recorded for all participants.

Focus groups

Focus groups comprised four to seven participants within the same age range (e.g. 8–9y, 12–13y, and 16–17y) and a fair representation of both sexes. All focus groups were chaired by the same moderator (MH). In addition, an assistant was present (CS) who was responsible for the observation of the group and the tape recording of the data. The tape recordings were transcribed verbatim immediately after the focus group had been conducted.

During the focus groups, participants were asked 11 open-ended questions regarding the concept of health status, based on the ICF (Table 1).21 Questions were adapted to a level that individuals in the age group of 8 to 12 years could understand. To make it more comprehensible for the children to understand the questions, we showed a presentation with animations. Participants were free to refer to any problems or limitations, which they were experiencing or had previously experienced. They were also free to take part in the discussion if they had no problems or difficulties.

| Questions of ICF regarding quality of life |

|---|

| 1. If you think about your body and mind, what does not work the way it is supposed to? |

| 2. If you think about your body, in which parts are your problems? |

| 3. If you think about your daily life, what are your problems? |

| 4. If you think about your environment and your living conditions, what do you find helpful or supportive? |

| 5. If you think about your environment and your living conditions, what barriers do you experience? |

| 6. If you think about yourself, what is important about you and the way you handle your disease? |

| 7. How would you rate your quality of life? |

| 8. How satisfied are you with your health? |

| 9. How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily activities? |

| 10. How satisfied are you with your personal relationships? |

| 11. How satisfied are you with the conditions of your living place? |

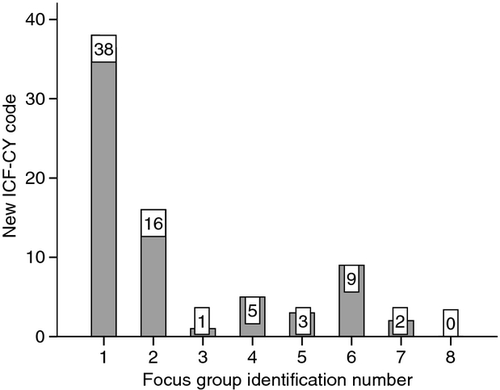

The total number of focus groups was determined by saturation, which means to the point at which an investigator has obtained sufficient information from the focus groups. This refers to the point in the data gathering process when a consecutive focus group reveals no additional information that was not obtained before.21 For this purpose, the raw transcripts were judged by the study coordinator (CS) after each focus group session and compared with the transcripts from previous focus groups. When no new information was revealed in the raw transcripts, all problems and difficulties mentioned in each consecutive focus group were linked to the corresponding category of the ICF-CY. Saturation was reached at the point a consecutive focus group did not reveal any additional ICF-CY categories, next to the ones obtained in previous focus group sessions.20, 21

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis followed the method of ‘meaning condensation’,24 performed using a three-step process, which was executed independently by two researchers (CS and EB) after each focus group.

In the first step, the transcriptions of the answers to the questions of the focus groups were carefully read. In the second step, the data were divided into meaning units. A meaning unit is defined as a specific unit of text, a few words, or a few sentences with a common theme. In the third step, the two researchers identified the theme that dominated a meaning unit, the so-called meaningful concept; a meaning unit can contain more than one meaningful concept. All above-mentioned steps were performed according to standardized ICF rules, as described by Cieza et al.25

After these steps, all unique meaningful concepts were linked to the appropriate ICF-CY categories according to published linking rules.25, 26 Linked ICF-CY categories were defined as relevant concepts of functioning for individuals with OBPI. After each focus group, the linked ICF-CY categories were added to the list of all nominated ICF-CY categories until saturation was reached.20, 21

All steps were done independently by the two researchers to ensure the validity of the qualitative analysis and the linking to the ICF-CY identification of the (sub)concepts in the complete transcribed text of the focus groups. Disagreement between the two researchers was resolved by discussion and the informed decision of a third expert (TVV) to create a final agreed-on version of the linked ICF-CY categories.

Results

Description of participants and focus groups

In total, parents of 69 children were informed about the study design and the purpose of the study by telephone by the study coordinator. A total of 48 children with OBPI (25 male and 23 female) with a median age of 11 years 6 months (range 8–17y) participated in the study. Of these children, 22 had a C5–C6 lesion, 17 children had a C5–C7 lesion, eight children had a C5–T1 lesion and one child had a C5–C8 lesion. Six children had received only conservative treatment and 42 had received surgical treatment (nerve repair surgery [n=39] and/or secondary soft tissue procedures [tendon transfers, contracture releases or other; n=22]) (Table 2). Twenty-one children did not participate because the scheduled time was inconvenient or the child did not like the focus group setting. Saturation of data was reached after performing eight focus groups (Fig. 1). The mean duration of the eight focus groups was 65 minutes (range 60–76min).

| Focus group identification number | Number of patients | Sex (M:F) | Age range (y) | Conservative treatment | Nerve repair | Orthopaedica surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 5:1 | 10–12 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 2 | 7 | 4:3 | 10–11 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| 3 | 5 | 3:2 | 9–9 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| 4 | 7 | 2:5 | 8–9 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| 5 | 5 | 5:0 | 12–13 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | 7 | 3:4 | 13–14 | 1 | 6 | 5 |

| 7 | 7 | 1:6 | 16–17 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 8 | 4 | 2:2 | 14–17 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Total | 48 | 25:23 | 8–17 | 6 | 39 | 22 |

- a Orthopaedic surgery: either osteotomies and or tendon transfers of the upper extremity.

Concepts obtained in the qualitative analyses

In total, 363 unique meaning units were identified. A total of 2783 meaningful concepts were derived from the meaning units. Of these meaningful concepts, 2185 (79%) were linked to a total of 143 unique ICF-CY categories from the first to the fourth level of the classification.

Sixty-one of the 143 identified unique categories (43%) belonged to the ICF-CY component ‘activities and participations’, 31 categories (22%) belonged to ‘body functions’, 29 categories (20%) belonged to ‘environmental factors’, and 22 categories (15%) belonged to ‘body structures’ (Table SI, supporting information published online).

Overall, 598 concepts were not classified on the level of ICF-CY categories but could only be linked to ICF-CY components in general. Of these, 269 (269 out of 598; 45%) were linked to the ICF-CY component ‘personal factors’ and 126 (21%) were coded as ‘health condition’. The remaining 203 concepts (34%) could not be linked to any ICF-CY category (e.g. quality of life in general, disease management, time-related aspects, and variability of functioning).

Body functions

Regarding ‘body functions’, the collected data of the focus groups were linked to the following four ICF-CY chapters: ‘mental functions’ (B1), ‘sensory functions and pain’ (B2), ‘neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions’ (B7), and ‘functions of the skin and related structures’ (B8) (Table SI). The following categories were identified in all eight focus groups: ‘mobility of joint functions, other specified’ (B7108) and ‘power of muscles of one limb’ (B7301). Concerning mobility of joint functions, in all focus groups, children mentioned difficulties with putting their arm above their head; for example, ‘I find it hard to reach for something’.

Body structures

The following three chapters of the component ‘body structures’ were represented by the identified ICF-CY categories: ‘structures of the nervous system’ (S1), ‘structures related to movement’ (S7), and ‘functions of the skin and related structures’ (S8) (Table SI). Children most frequently mentioned problems with their arms, shoulders, hands, and nerves. Some children were uncomfortable with the difference in size and shape of their shoulder and arm compared with the size on the unaffected side. Children also mentioned emotional difficulties regarding scars over the length of the calves, which were the result of harvested sural nerves, which were used as a graft for brachial plexus nerve repair. The following categories were identified in all focus groups: ‘structure of sympathetic nervous system’ (S140), ‘structure of upper arm’ (S7300), and ‘structure of hand’ (S7302).

Activities and participation

All nine chapters of the component ‘activities and participation’ were represented by the identified ICF-CY categories (Table SI). Problems with sports – such as gymnastics at school, football, and dancing – were mentioned as a problem in all focus groups. Exercises with ropes and rings, handstands, and throwing the ball with two hands were described as difficult. Another frequently mentioned problem was swimming; for example, ‘When I swim I get very tired quickly, I get cramps and it keeps getting more annoying’. Other frequently mentioned difficulties included grasping, writing, eating properly two-handed, and bicycling. The following categories were identified in all focus groups: ‘manipulating’ (D4402), ‘washing body parts’ (D5100), ‘reaching’ (D4552), and ‘sports’ (D9201).

Environmental factors

All five chapters of the component ‘environmental factors’ were represented by the ICF-CY categories identified by linking the content of the focus groups (Table SI). The most important facilitators in a child's life were the parents; for example, ‘Eating a pastry that I really can't cut (is a problem), so my mother, sister or father cuts it for me’. Some participants mentioned that they used general products of daily living in a different way to make things easier. The categories ‘general products and technology for personal use in daily living’ (E1150) and ‘immediate family’ (E310) were identified in all focus groups.

Not classified concepts

Several concepts were related to the ICF-CY component ‘personal factors’, which is not yet further specified in categories. In this component, concepts related to accepting the disease and adapting to the disease and its wide range of consequences were a recurring theme in all focus groups; for example, ‘I do not have difficulties with washing my hair, because I use my other arm’.

Several concepts contained in the meaning units were linked to the ICF-CY component ‘health condition’; for example, when children were asked about the aetiology of an OBPI, few children knew the correct cause of their injury or which structures were involved.

Some concepts contained in the meaning units could not be linked to any of the ICF-CY components because they are not covered by a specific ICF-CY category or the content of the concepts was not specific enough to be linked, for example ‘It's annoying’.

Discussion

This study describes the perspective of the individual with an OBPI with respect to the four ICF-CY components (i.e. body functions, body structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors) using focus group methodology. The results of this study affirm the complexity and multidimensionality of the problems encountered in the daily lives of children with an OBPI.

With respect to ‘body functions’, mobility and movement of the arm were found to be impaired, but a number of children did not feel any limitations regarding their hand and arm function. This could probably be explained by coping strategies, which are within the scope of ‘personal factors’.

Older children tended to experience fewer problems with their disability because, as they grew older, they had learned to accept their condition. The finding that the number of problems encountered by teenagers with OBPI is limited is in line with the results from a study by Strombeck and Fernell.16 That study compared the results of a self-report questionnaire – concerning daily life, school performance, and friendships – in 51 adolescents with OBPI and 116 age-matched individuals, concluding that adolescents with OBPI report that teenage life is comparable to that of their able-bodied peers.16

Concerning ‘body structures’, big scars on the calves made some children insecure about wearing skirts or shorts. At our centre, since 2000 harvesting of the sural nerve has been done endoscopically through small incisions, but with an open technique before that time. Cosmetic aspects of the legs are currently not included in any studies or outcome measures used in studies of individuals with OBPI. Concerning cosmetic appearance of the shoulder and arm, some children stated differences in shape and size. Some older girls mentioned they had some difficulties with their bra strap, which frequently slid off the affected (hypoplastic and slightly deformed) shoulder. Very little is known about the perspective of cosmetic appearance in this population27 and further studies should be conducted to explore this important aspect.

Regarding ‘activities and participation’, our study confirmed the broad spectrum of limited activities and restricted participation usually found in children with an OBPI. Our study found that, in particular, activities requiring the involvement of both hands, such as many sports activities, were perceived as limited. This finding is in concordance with the results of the study by Bae et al.,12 who concluded that nearly half of children with OBPI perceived difficulty in sports participation, although in that study the participation rates in team and individual sports were equivalent to healthy children. Kirjavanen et al.17 also found that a considerable proportion of individuals reported having problems with bicycling, cross-country skiing, or swimming.17 These problems were related to either muscle weakness or joint stiffness of the affected upper limb. Another study showed that most activities, which can be done with one hand, are not a problem, as children reported using their non-involved hand.15 However, most sports activities require good functional use of two hands and were thus often mentioned as problematic.

Difficulties with self-care were mentioned in all focus groups; however, children did not perceive self-care as a problem. This is in accordance with the results of a study which found that children with OBPI without hand impairment did not have a self-care activity limitation as measured by the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory. A deficit in self-care ability was found only in those with hand impairment compared with ‘peers’. It was unable to discriminate between those without hand impairment and their peers.13

With respect to ‘environmental factors’, the interaction of the participant regarding contextual factors such as family, friends, school, individual and societal attitudes, and the health system may act as barriers or facilitators. Immediate family was often mentioned as a facilitator. This result supports the importance of the family relationship and the support received from family members, especially the parents. Friends were perceived as facilitators after the participant had disclosed his or her condition. This finding is in line with the study by Strombeck and Fernell,16 who found that about 90% of the adolescents in the study were very satisfied with their friends, both at school and at home, and they did not want any changes to take place at all. School was not seen as a barrier and teachers were also mentioned as facilitators. Assistive products and technology, specially designed for each individual for personal use in daily living, were not used as much as generally available products; the children would rather climb on the kitchen counter to be able to reach for the cabinets than use an assistive device.

Regarding the component ‘health condition’, most children had little knowledge about the aetiology of an OBPI or which structures are involved. This is probably a result of a lack of explanation by parents and health professionals, or a result of the emotional association and/or difficulty level of the cause of this condition. This finding is in line with the results of another study among the parents of 44 children, which found that the majority of parents thought that the delivery had been ‘very difficult’ and that it was ‘badly’ handled by the gynaecologist.28 In that study, parents tended to blame the doctor, which could probably have caused children to think the doctor was accountable. These findings emphasize the need for health practitioners to put more effort into explaining to parents and children what the cause of this disability is.

Children with an OBPI described a large variety of problems and difficulties. This complexity and multidimensionality of problems and difficulties was also described by Bult et al.29 in children or young people with different forms of physical disability such as cerebral palsy.29 Gunel and Mutlu30 used the ICF for children with cerebral palsy and concluded that participation restrictions and activity limitations strongly affected functional independence.30 To achieve optimal rehabilitation for children with a physical disability, it is important for the treating professionals to be aware not only of all the possible consequences on the level of daily activities and participation in society, but also of the contextual factors that may positively or negatively influence the perceived limitations. However, it is important to emphasize that children with an OBPI are usually independent and have adapted well to the limitations of the affected limb. Furthermore, in general, only one limb is affected.

This study had a number of limitations. First, it was conducted in one centre in one country only. This is likely to be insufficient to cover the entire scope, taking into account cultural variation, which makes further qualitative studies with different diagnostic groups in different parts of the world desirable. Furthermore, we performed this study with young children, which probably forced us to adapt the questions to a more suggestive level than would be the case in adult research. Another limitation is that surgically treated children, most likely those children with more severe injuries, may be overrepresented in our study and therefore the study may not be generalizable to children with all severities of OBPI. A limitation regarding the ICF-CY is that the results of analyses of transcripts in qualitative research may have been affected. However, several concepts could not be linked to the ICF-CY, which indicates that participants in the study were indeed able to think about their condition outside the context of the ICF-CY. Furthermore, the linking process was performed by two researchers and, although linking rules were carefully followed, it remains unclear whether other researchers would have decided differently. However, the disagreement between the two researchers in this study was low and was quickly resolved by discussion. In addition, our study focused on problems and limitations (disabilities) rather than abilities. Although this is in line with previous, similar studies of individuals' perspective on their condition,31-33 it implies that positive aspects of functioning may be underrepresented. However, with personal and environmental factors, it was explicitly explored which of these worked as barriers and which worked as facilitators.

Conclusion

In children and adolescents with OBPI, ‘activities and participation’ was the ICF area most affected, followed by ‘body functions’, ‘structures’, and ‘environmental factors’. Nevertheless, these children with an OBPI have adapted well to the limitations of their affected limb.

More data from the perspective of patient are needed, which could serve as a guide to adapt clinical care and research to a more patient-centred level, allowing both parents and patients to have more insight into their functional limitations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Leiden Brachial Plexus Injury Study Group: J H Arendzen, K S de Boer, D Steenbeek (Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Leiden University Medical Center), S M Buitenhuis (Department of Physical Therapy, Leiden University Medical Center), J G van Dijk (Department of Neurology, Leiden University Medical Center, A A Kaptein (Department of Medical Psychology, Leiden University Medical Center), J Nagels (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Leiden University Medical Center), and W Pondaag Department of Neurosurgery and Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Leiden University Medical Center).