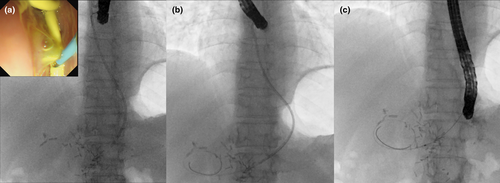

Troubleshooting the migration of endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreatic duct drainage stent to avoid repuncture

Abstract

Watch a video of this article.

BRIEF EXPLANATION

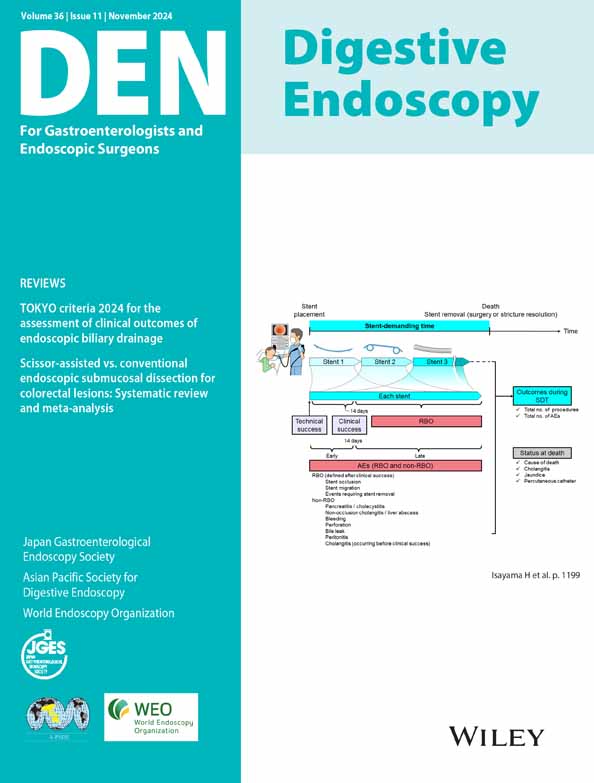

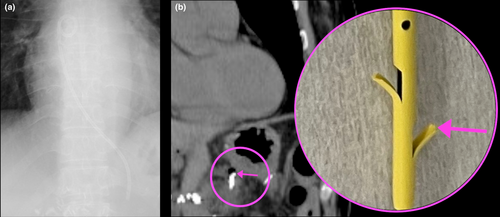

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage effectively treats difficult transpapillary drainage.1, 2 However, EUS-guided pancreatic duct drainage (EUS-PD) is technically challenging, as repuncture should be avoided to prevent pancreatic fluid leakage; we describe a technique for EUS-PD stent migration that enables us to avoid repuncture (Video S1).3 A 54-year-old woman, who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer, experienced recurrent cholangitis and pancreatic stones due to anastomotic stenosis. Endoscopic drainage using a single-balloon enteroscope (SIF-H290S; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was attempted, but identifying the pancreatic duct orifice was difficult. Therefore, EUS-PD was performed to secure the route for stone removal. A 19G needle (EZ shot 3 plus; Olympus) was used to puncture the dilated pancreatic duct at the tail. The drill dilator (Tornus ES; Olympus) could not pass the stone. A 4 mm dilating balloon (REN TYPE-IT; Kaneka, Osaka, Japan) was used. After adequate dilation, a 7Fr plastic stent (TYPE IT; Gadelius Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was deployed, but its tip failed to cross the stone and anastomosis, so the stent was placed in the main pancreatic duct proximal to the stone.4 Vomiting and fever occurred postprocedure, and radiography revealed stent migration into the esophagus. However, computed tomography revealed the stent tip barely lodged in the pancreatic duct owing to the large flap. Therefore, using a side-viewing duodenoscope (TJF-260 V; Olympus), a guidewire (VisiGlide II; Olympus) was successfully inserted through the stent flap and guided into the jejunum. The stent was removed using forceps (Figs 1, 2). The tract and anastomotic site were sufficiently dilated using a drill dilator, and a 6 mm fully covered self-expandable metal stent (EGIS biliary stent, 6 × 10 mm; SB-Kawsumi, Kanagawa, Japan) was successfully placed. One month later, the stone was successfully removed by the EUS-PD route. A plastic stent has two large flaps at its tip, and even if it migrates, the flap may remain in the pancreas.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Author T.I. received honoraria for his lectures from Olympus and Boston Scientific. The other authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.