Endoscopic findings of esophagogastric junction in children

Abstract

Esophagogastric landmarks are recognizable in the same way both in children and in adults, and palisade-shaped vessels can be observed at the distal position of esophageal mucosa, even in infants. Few studies have been done in respect to Barrett's esophagus (BE) in children. Incidence of endoscopically suspected BE among all children undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is approximately 0.25–1.4%, but can be up to 9.7% in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Some data suggest that BE is an acquired disorder and point to the possibility of a congenital component in combination with severe mucosal injury. Recent reports noted that multilayered epithelium (ME), which shows morphological and immunocytochemical characteristics of both squamous and columnar epithelium, is associated with goblet cell metaplasia in adult patients with columnar-lined esophagus. The role of ME in the development of intestinal metaplasia in children is uncertain. Furthermore, detailed mechanisms about how short-segment BE (SSBE) changes to long-segment BE (LSBE) are not yet well understood. Further studies are required to understand the pathological esophagogastric junction (EGJ) and BE in children based on reliable epidemiological data and analysis especially in children who have reflux symptoms. Better understanding of the pediatric EGJ and BE may allow improved diagnosis, monitoring, therapy and, therefore, prognosis of GERD-related disorders in adulthood.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) occurs when gastric contents come back up into the esophagus. It often presents in infants as a normal or a physiological condition; however, most GER cases in infants spontaneously resolve by the second year of life.1 Reflux in older children is more likely to become chronic. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has a pathological status, and can be defined as reflux associated with troublesome symptoms and/or complications.1, 2 Severe GERD in children can be complicated with failure to thrive, anemia, esophageal stenosis or even Barrett's esophagus (BE).1, 2

BE is a preneoplastic condition, develops as a consequence of chronic GERD, and predisposes to the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma.3 Through endoscopy, BE is identifiable from the replacement of normal squamous epithelium by columnar epithelium and columnar mucosa extending above the gastroesophageal junction, lining the distal esophagus.3, 4 Different types of columnar epithelium in the esophagus have been described: gastric cardia-type, gastric fundic-type and intestinal metaplastic-type with goblet cells and with or without brush border.5 Although all three types often coexist in columnar-lined esophagus, definitive diagnosis of BE requires esophageal biopsy showing intestinal metaplasia (IM) with goblet cells which is called specialized columnar epithelium.3-6 It is recognized that intestinal metaplastic epithelium has malignant potential. BE in the pediatric age group may run a continuous course until adulthood; however, molecular biology has not yet been able to identify a single molecular marker that would allow recognition of those patients at risk for adenocarcinoma.5, 7

In the present review, we would like to promote understanding of the endoscopic appearance of the EGJ and BE in children.

Endoscopic Appearance of EGJ in Children

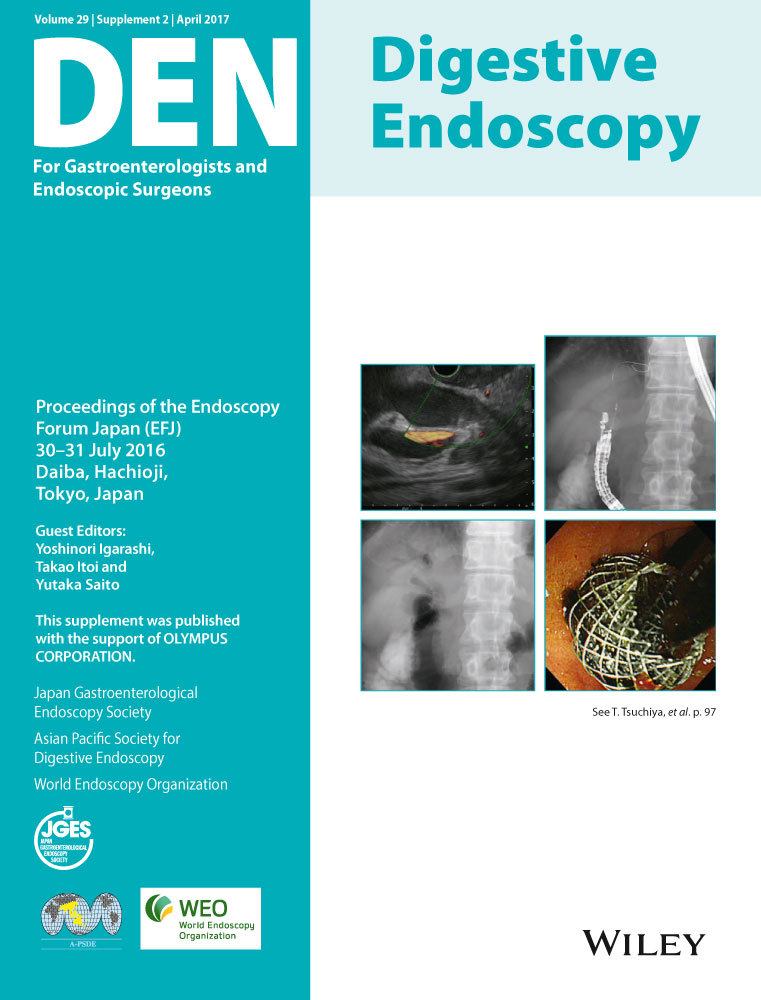

Esophagogastric landmarks are similarly recognizable both in children and in adults. Figure 1 shows the endoscopic appearance of EGJ in a 7-month-old infant without GER symptoms. The landmarks, which indicate diaphragmatic pinchcock, lower esophageal sphincter zone, gastric folds and Z-line, are easily observed at the same level. Moreover, even in infants, palisade-shaped vessels are visible on the lower esophageal mucosa. In Japan, the landmark of the EGJ in endoscopic diagnosis is the distal end of the palisade-shaped vessels, whereas the endoscopic landmark for EGJ in Western consensus is defined as the proximal margin of the gastric fold in a minimally distended condition.8

How Often Do We See BE in Children?

Incidence of histological BE among the general adult population in the West is approximately 2%;9 however, it increases to 6–12% in patients with GERD symptoms.10, 11

As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of endoscopically suspected BE or BE with IM is reported less often in children than in adults.12-17 Cohen and colleagues reported a 7-year retrospective review conducted in the UK which revealed an estimated prevalence of endoscopically suspected BE to be 0.0024% in the general pediatric population. It increased to 0.8% in children referred for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and up to 5.5% in patients with esophagitis.16 Among children who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy for >9 months, Hassall et al. reported that BE and BE with IM was identified in 9.7 and 4.8%, respectively.14 Accordingly, BE seems to be more prevalent than previously suspected in risk-stratified pediatric patients with severe GERD.14

| Author (year) | Study design | Study period | Selection | Country | No. cases | BE suspected by endoscopy (%) | BE with IM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies in children with GERD | |||||||

| El-Serag et al.13 (2002) | Retrospective study | 1996–2000 | GERD patients without neurological deficits and congenital esophageal anomalies | USA | 402 | 2.7 | 0 |

| Hassall et al.14 (2007) | Retrospective study | 1989–2004 | All children with PPI | Canada | 166 | 9.7 | 4.8 |

| Studies in children referred for EGD | |||||||

| El-Serag et al.15 (2006) | Retrospective multicenter study | 1999–2002 | All procedures for any indication | USA | 6731 | 0.25 | 0.13 |

| Cohen et al.16 (2009) | Retrospective study | 2000–2007 | All procedures for any indication with esophageal biopsy | UK | 1453 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Nguyen et al.17 (2011) | Prospective multicenter study | 2006–2007 | All elective procedures without neurodevelopmental and tracheoesophageal disorders | USA | 840 | 1.4 | 0.12 |

| Present study | Retrospective study | 2005–2015 | All procedures for any indication | Japan | 1323 | 0.8 | 0 |

- BE, Barrett's esophagus; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; IM, intestinal metaplasia; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Despite the scarcity of data concerned with the prevalence of pediatric BE, recent studies have suggested an increase in BE in the pediatric population.12 Furthermore, a previous review shows that BE may develop in children who have reflux symptoms for a mean period of 5.3 years and results in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma in children.12

How Often Do We See BE in Japanese Children?

Few studies have been done on pediatric BE in Japanese children. In 2001, Ida and colleagues investigated BE among 19 cases of GERD with neurological impairment (only Japanese literature is available). Five of their cases showed columnar-lined esophagus by EGD, and three of the five had BE with goblet cell metaplasia. Three cases with definitive BE were all male and aged 6 to 9 years. Of note, all the BE patients had hematemesis and two of them were complicated by anemia. Interestingly, the authors speculated that non-acid reflux and food allergy might be the responsible factors for developing BE.

We retrospectively reviewed the endoscopic database of Shinshu University Hospital at Nagano prefecture, Japan to investigate the prevalence of BE, as our center is one of the largest pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy centers, and five pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopists currently carry out approximately 200 diagnostic pediatric endoscopies per year. Pediatric patients who were referred for EGD were included in this survey. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of Shinshu University (ID:3333). During EGD, locations of the major esophagogastric landmarks were routinely documented, and hiatal hernia was considered when the tops of the gastric folds were proximal to the diaphragmatic pinchcock. Presence and severity of erosive esophagitis were graded according to the Los Angeles classification (Grade A to D).18 Extent of the Z-line was measured using the length of circumferential and maximal extent from the top of the gastric fold (Prague classification).19 Routine biopsy specimen was taken from the duodenal descending part, duodenal bulb, gastric antrum, gastric corpus and lower esophagus regardless of the endoscopic findings. If the length of columnar-lined esophagus was >0.5 cm, biopsy was taken from the metaplastic columnar mucosa to confirm the presence of IM. Among 1323 cases, we detected 10 (0.8%) Japanese patients with endoscopically suspected BE; however, none of the 10 proved to have IM by histopathological evaluation. Median age of the patients with suspected BE was 10 years (range 7–14), and seven of them were male. Patients who had fundoplication, repaired esophageal atresia or severe neurological impairment were referred to another center for EGD to evaluate pre/post-pediatric surgery and, thus, were not included in this cohort. Two patients had coexisting erosive esophagitis. Simple hiatal hernia was reported in two of 10 cases, both of whom had obesity.

It is obvious that several factors could play a role in the prevalence of BE, including interobserver variability, different referral practice, antireflux treatment at the point of endoscopy, different diagnostic criteria for landmarks of BE, and the precise site or number of biopsies. Interestingly, the prevalence of endoscopically suspected BE in Japanese children referred for EGD was in agreement with those of Cohen and colleagues from the UK.16

On the contrary, BE with IM was not detected in our cohort. Thus, our explanation is that most of our cases had short-segment metaplastic mucosa (<1 cm) and they did not have risk factors of BE, including neurological impairment, chronic lung disease, repaired esophageal atresia, or malignancies treated with chemotherapy.17, 20-22 Furthermore, intestinal type of metaplasia was described in those >10 years of age, but was rarely reported in those <5 years of age among the pediatric population.23-25 IM possibly occurs as a function of time and severity of reflux. Further explanation could be sampling error to identify IM. To minimize the sampling error, Hassall took a large number of specimens using a large cup (‘jumbo’) forceps and reported two pediatric cases with pure cardia-type mucosa as an esophageal metaplastic condition.26

Is BE a Congenital or an Acquired Disease?

This topic was a matter of debate about 20 years ago. Hassall concluded that BE is an acquired disorder and pointed out the possibility of a congenital component in combination with severe mucosal injury.27 The concept of BE being an acquired condition related to GERD has been supported by most of the following literature, as the longer duration of reflux predicts BE both in adults28, 29 and in children.13, 15

To understand the pathological changes at the EGJ, the location, extent, and even the existence of cardiac mucosa were debated. According to an autopsy study in both fetus and infant cases, De Hertogh and colleagues reported that cardiac mucosa exists since 13 weeks gestational age in all samples and is present around the esophageal perimeter, has a mean length of 0.3–0.6 mm, and is located proximal to or at the EGJ if it is defined as the angle of His.30

To avoid over- or underdiagnosis of endoscopically suspected BE, firm diagnosis criteria were established. Thus, the Montreal Global Consensus Document revised the definition of BE to involve not only intestinal-type metaplasia but also pure gastric cardia-type metaplasia as part of the spectrum of BE.4 Recently, Lupu and colleagues reported the extent of cardiac mucosa and heterotopic gastric mucosa in the distal part of the esophagus in a teenager and pointed out that heterotopic gastric mucosa was mimicking short-segment BE.31

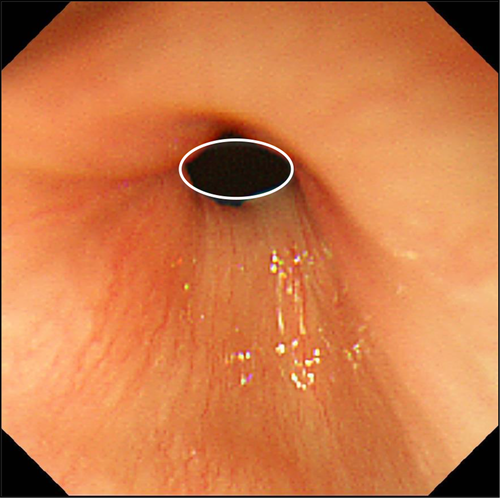

Considering the congenital component, we reviewed all endoscopic pictures of EGJ in 43 patients aged ≤2 years old. Extent of small tongue-like Z-line without any symptoms of GER was present in a 2-year-old boy (Fig. 2). Biopsy specimens were not taken from columnar-lined epithelium or squamous cell mucosa, because the indication for EGD was foreign body removal. In such a case, we could speculate about the possibility of congenital ectopic gastric mucosa or metaplastic extension of cardiac mucosa into the distal esophagus.

How SSBE Changes to LSBE in Children

Case report

One pediatric case presented as short-segment BE (SSBE) which developed to long-segment BE (LSBE) during follow up of GERD over a decade. The patient is currently a 17-year-old boy. Since the age of 2 years, he developed chronic cough and recurrent postprandial chest pain. The symptoms persisted and at age 6 years he was referred to Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health. His condition was complicated by anemia, torticollis and failure to thrive; height (−2 SD) and weight (−2.5 SD). Furthermore, he had cow's milk allergy, but, otherwise, no serious comorbidity disorders. After evaluation of upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract using esophageal pH monitoring, esophageal manometry and EGD, he was diagnosed to have small hiatal hernia with reflux esophagitis and further specified as a case of Sandifer syndrome. He responded well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Of note, occasional pediatric patients who present with associated neck contortions (arching, turning of head) may be characterized as having Sandifer syndrome.

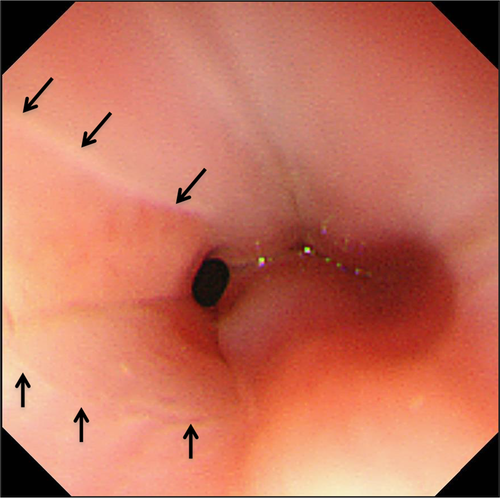

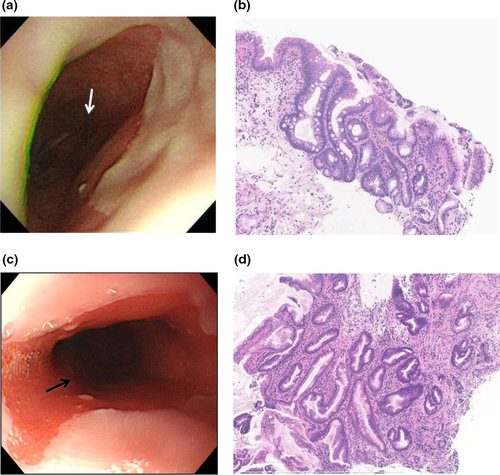

At the age of 8 years, abdominal pain and vomiting relapsed and, as the patient had tarry stool and anemia, emergency EGD was carried out. EGD showed no active upper GI bleeding, but small hiatal hernia and reflux esophagitis (Los Angeles classification Grade A) were identified (Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, several biopsies were taken from the EGJ which showed an elongated esophageal papilla suggesting reflux esophagitis. As the patient was regarded as having relapsed reflux esophagitis, he received a double dose of PPI and, fortunately, showed a good response with disappearance of his symptoms. Recently, we reviewed a biopsy specimen from the Z-line and multilayered epithelium (ME) was observed (Fig. 3b,c).

In 1997, Boch and colleagues reported ME in two patients with BE.32 Immunocytochemistry shows a morphological character of both squamous and columnar epithelium, and mucin histochemical analysis shows features of colonic differentiation and esophageal mucosal gland duct epithelium. ME was observed in 30–41% of BE compared with 0–6% in non-BE cases and is suggested to present a transitional stage in the development of goblet cell metaplasia in adults.33-36

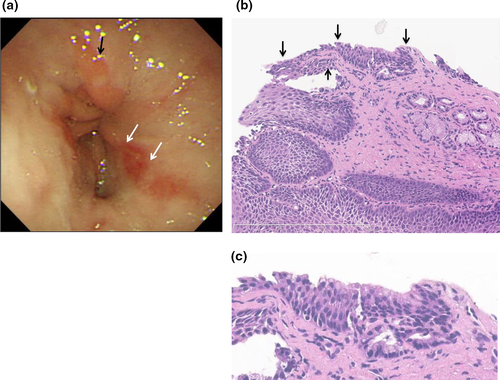

Subsequent EGD evaluation for over 7 years in the present pediatric patient showed ≤2–3-cm pink tongue mucosa with pure cardiac-type gastric glands with no erosion on the distal esophagus. During the follow-up period, the patient complained of nausea following the intake of PPI; therefore, PPI therapy was discontinued, but, despite this, he remained asymptomatic. Antireflux surgery was discussed; however, because of his being asymptomatic, he and his parents were not convinced. Then, at age 15 years, according to Prague criteria, the tongue of pink mucosa extended C 3 cm and M 3.5 cm, and goblet cells were observed at 1 cm above the top of the gastric fold (Fig. 4a,b). Accordingly, by histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with LSBE (≥3 cm of columnar metaplasia) with IM.

At the age of 16 years, BE extended to C 4 cm and M 5 cm. Small white islands were observed within metaplastic epithelium. Biopsy specimen within 1 cm distal to the top of Z-line showed IM with papillary hyperplasia (Fig. 4c,d).

Although the patient was asymptomatic for approximately 10 years of follow up, he progressed from SSBE to LSBE. To our knowledge, this is the first case to be reported in children in which ME was observed at the squamocolumnar junction before extending to the metaplastic mucosa. As reported in adults, ME may also play a role in the development of goblet cell metaplasia in the pediatric age group. However, more detailed investigation including immunophenotypic characteristics of columnar epithelium, such as Cdx2, MUC2, CD10, HGM, MUC5AC and MUC6, are needed. This case needs strict follow up by periodic endoscopic surveillance for early detection of dysplasia and consequent adenocarcinoma.

Future Perspectives

More evidence based on reliable epidemiological data and analysis is required to understand pathological EGJ and BE in children. The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma is 30–125-fold higher in BE cases compared to the general Western population.37 Recently, molecular biomarkers were reported to be risk-stratifying for more efficient surveillance endoscopy in both children5, 7, 38 and adults.39, 40 These results may guide clinicians to decide how to manage children with GERD, in reference to endoscopic evaluation and future therapy.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Professor Hidenobu Watanabe at Niigata University School of Medicine for his kind instruction of pathological diagnosis and Dr Lika'a Fasih Y. Al-Kzayer for her English editorial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.