Basic principles and practice of gastric cancer screening using high-definition white-light gastroscopy: Eyes can only see what the brain knows

Abstract

Endoscopic diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumors consists of the following processes: (i) detection; (ii) differential diagnosis; and (iii) quantitative diagnosis (size and depth) of a lesion. Although detection is the first step to make a diagnosis of the tumor, the lesion can be overlooked if an endoscopist has no knowledge of what an early-stage ‘superficial lesion’ looks like. In recent years, image-enhanced endoscopy has become common, but white-light endoscopy (WLI) is still the first step for detection and characterization of lesions in general clinical practice. Settings and practice of routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) such as use of antispasmodics, number of endoscopic images taken, and observational procedure are customarily decided in each facility in each country and are not well standardized. Therefore, in the present article, we attempted to outline currently available evidence and actual Japanese practice on gastric cancer screening using WLI, and provide tips for detecting EGC during routine EGD which could become the basis of future research.

Medical Interview Prior to Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Medical interview before esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is important in terms of the following two points. One is to confirm indication of the EGD and the other is to assess risk of examinees. Whether indication for EGD is to screen for early gastric cancer (EGC) or to make a diagnosis of a patient's symptoms or abnormal findings in other diagnostic examinations should be distinguished. In the screening endoscopy, the entire gastric mucosa is thoroughly observed to detect any suspicious findings for neoplasia, whereas only the presence of apparent lesions that may cause symptoms or abnormal image findings are investigated. Although endoscopy is usually intended to make a diagnosis of symptoms or abnormal findings in other diagnostic images, EGC are often found in patients with neither obvious symptoms nor abnormal findings in other diagnostic tests.1 Therefore, in high-risk patients, it is important to screen for EGC unrelated to symptoms or abnormal findings of other diagnostic tests during EGD. The examinee should be asked about status and history of eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori),2-4 family history of gastric cancer, smoking and drinking habits.5-8 Another reason for the medical interview is to reduce adverse events of the examination. Medical history, comorbid diseases (e.g. gastric cancer or ulcers, surgery, benign prostatic hyperplasia, glaucoma, serious cardiovascular or respiratory disease), drug allergies, and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or antithrombotics should be inquired.9

Pretreatment

Giving oral mucolytic agent (pronase)10 and an anti-foaming agent 11 reduces time and effort for washing out mucus or bubbles to improve quality of observation. A mixture of 4 mL anti-foaming agent (dimethicone, Gascon® 20 mg/mL; Horii Pharmaceutical Industry, Osaka Japan), 20 000 U mucolytic agent (Pronase MS®; Kaken Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), and 1 g sodium bicarbonate dissolved in 50 mL water is given 10 min before the examination.12

Usefulness of a topical pharyngeal anesthetic is controversial although it is commonly used before gastroscopy. 13, 14 UK data show that topical pharyngeal anesthetics are always used in 63%, sometimes in 17%, and not used in 20% of all cases.15 Because topical pharyngeal anesthesia does not affect patient tolerance and procedure performance in patients receiving conscious sedation,16, 17 pharyngeal anesthetics can be omitted when potential risk of allergic shock is considered.18

Although gastric peristalsis may cause not only oversight of lesions but also prolongation of the examination, there has been no study that demonstrates effectiveness of antispasmodics on improvement of diagnostic accuracy of gastroscopy. Hedenbro et al. reported that giving i.m. and i.v. butylscopolamine bromide (Buscopan® 20 mg) Boehringer Ingelheim Japan, Tokyo did not reduce gastric peristalsis, whereas it increased discomfort caused by dry mouth.19 Glucagon (Glucagon G Novo® 1 mg) Eisai Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan is used as antispasmodic and does not increase heart rate compared to butyl scopolamine bromide but reactive hypoglycemia can occur.20 Recently, efficacy of topical administration of l-menthol (Minclea®; Nihon Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) on reduction of gastric peristalsis during EGD is indicated.21-23 This agent shows few side-effects. Need for antispasmodics during screening endoscopy needs to be clarified by well-designed clinical studies.

Sedation

The purpose of sedation is to reduce patient anxiety and discomfort, and to improve tolerability and satisfaction of the procedure. It also minimizes a patient's risk of physical injury during examination and provides the endoscopist with an ideal environment for the examination.24 Moderate sedation (conscious sedation)25 is recommended for endoscopy. A Ramsay score26 of three or four corresponds to moderate sedation (conscious sedation).27

Intravenous benzodiazepine drugs (i.e. midazolam, diazepam, and flunitrazepam) are feasible for sedation for endoscopy. Lee et al. indicated that i.v. midazolam was more effective than diazepam on improvement of patient satisfaction and on reduction of phlebitis.28 Because midazolam has an amnesic effect, it is necessary to notice whether a patient may not remember explanations given by the physician just after an examination.29

A meta-analysis showed both propofol and midazolam improve patient satisfaction and willingness to repeat EGD,30 but propofol is advantageous for short sedation and recovery times compared to midazolam.31 Old age only is not a reason to preclude the use of sedative drugs, but greater caution is necessary for elderly patients undergoing sedation and continuous monitoring during and after endoscopy is demanded.32 Attention should be paid to aspiration, delayed arousal, and the possibility of falls as a result of the body's inhibited defense reflex.33 Flumazenil reverses drowsiness and relieves respiratory depression induced by midazolam. The effect manifests approximately 120 s after i.v. injection.34 Because the action of flumazenil is usually shorter than that of benzodiazepines and sedation may recur, the patient should remain monitored.

Adverse effects of sedative drugs include respiratory depression, cardiovascular depression, bradycardia, arrhythmia, anterograde amnesia, disinhibition, and hiccups. According to a US guideline, the following precautions are important for sedation: patient assessment, knowledge about anesthetic/sedative drugs and resuscitation, monitoring and attendance of a person assigned responsibility for patient assessment, and preparation of a ventilator and emergency kits.35

Table 1 summarizes an outline of the interview, pretreatment, and sedation for safe and effective EGD.

| Contents | Item | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Interview | Understanding of examination purpose | Chief complaint, screening. |

| Past history | Gastric cancer/ulcer, surgery, benign prostatic hyperplasia, glaucoma, serious cardiovascular/respiratory disease. | |

| Allergy | Drugs, soy, egg. | |

| History of drug use | NSAIDs, anticoagulants/antiplatelet drugs. | |

| Family history | ||

| Lifestyle | Tobacco, alcohol use. | |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | History of examination/results, history of eradication. | |

| Pretreatment | Protease | Its use is desirable in countries with high rates of gastric cancer. |

| Antifoaming agent | Its use is desirable in countries with high rates of gastric cancer. | |

| Pharyngeal anesthesia | Not needed under sedation. | |

| Antispasmodics | It is not essential for screening examinations, and l-menthol can be substituted. | |

| Sedation | Midazolam | It is most frequently used. Initial dose is 2–5 mg. |

| Propofol | Clinical experience is increasing. | |

| Elderly subjects | There is no reason to avoid its use. | |

| Analgesic | May be given in combination with sedative agents. | |

| Patient monitor | Indispensable. | |

| Emergency cart | Indispensable. | |

| Ventilator | Indispensable. | |

| Antagonists | Flumazenil, naloxone hydrochloride. |

Observational Procedure

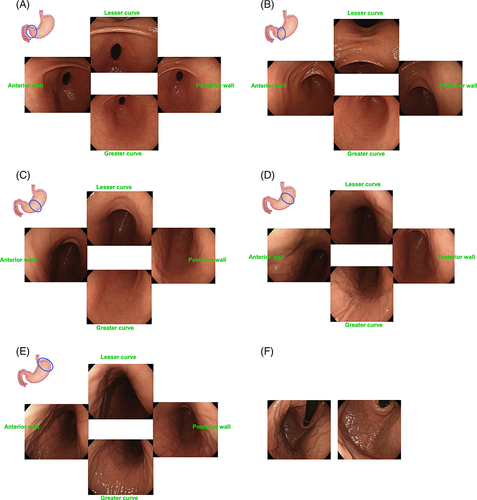

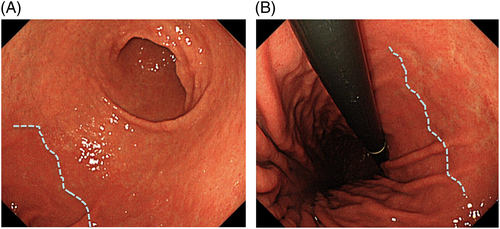

- After observation of the esophagogastric junction (Fig. 1A), the endoscope is inserted through the esophagus to the stomach, and the overall shape and hardness of the gastric corpus are observed immediately with only slight air insufflation (Fig. 1B).

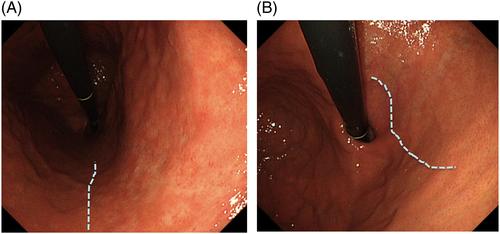

- After observation of the duodenum is complete, the lesser curvature, anterior wall, greater curvature, and posterior wall should be observed in each of the following five areas of the stomach: antrum, gastric angle, and lower, middle, and upper parts of the corpus (Fig. 2A–E).

- After observation by looking down, the endoscope's direction should be reversed at a high level in areas from the upper part of the corpus to the convexity of the greater curvature to observe the convexity with both long-distance and short-distance views (Fig. 2F).

After the general process of observation, differential diagnosis of minute mucosal changes found during the observational process should be conducted with caution by image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE). When judged to be necessary, the minimum necessary number of biopsy specimens should be obtained from the most suitable site.

Notable Endoscopic Findings During Screening EGD

Endoscopic findings associated with H. pylori infection

The presence of H. pylori infection, mucosal atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia are closely associated with the risk of gastric cancer. Therefore, to recognize relevant endoscopic findings of these conditions is important to assess the risk of gastric cancer and to detect EGC efficiently.

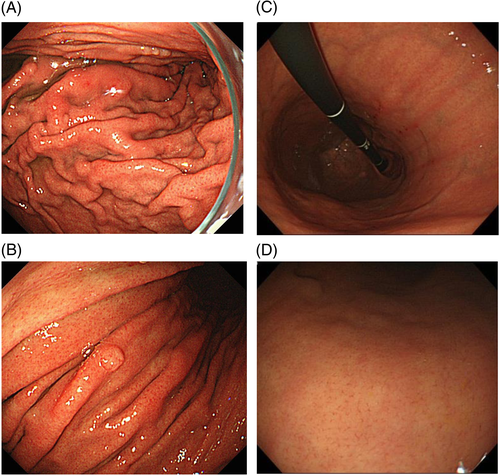

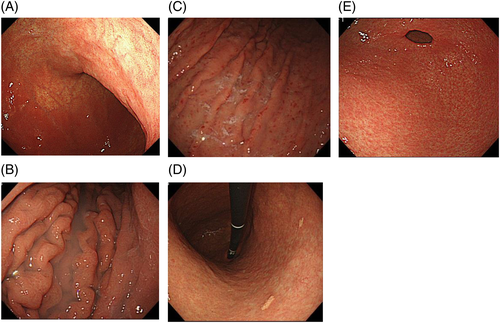

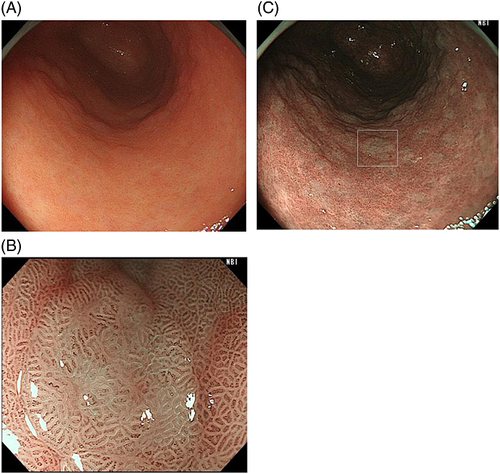

Because the development of gastric cancer from H. pylori-uninfected patients is extremely rare, the first step to access the risk of gastric cancer is to recognize patients with no history of H. pylori infection by endoscopy.41 Information about H. pylori infection by the urea breath test or antibody test is not always available before screening EGD. Small adhesion of mucus, regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC), and fundic gland polyps strongly suggest ‘H. pylori-uninfected gastric mucosa’ (Fig. 3).42

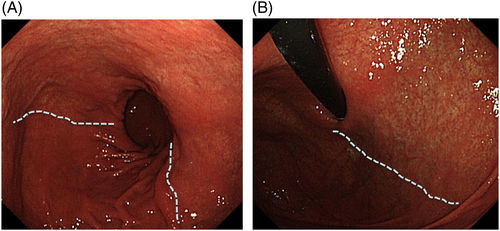

Conversely, atrophy of the gastric mucosa (Fig. 4A), meandering and thickening folds in the gastric corpus (Fig. 4B,C), xanthoma (Fig. 4D), or gooseflesh-like mucosa (nodular gastritis) (Fig. 4E) indicate a ‘gastric mucosa with current or previous H. pylori infection’.43 Nodular gastritis occurs frequently in women in their 20s or 30s, and is characterized by multiple granular protrusion caused by the lymphoid follicles in the mucosa. This finding is important in terms of association with risk of development of gastric cancer, particularly undifferentiated type, in young age.44-46

Diagnosis of EGC according to endoscopic atrophic mucosa

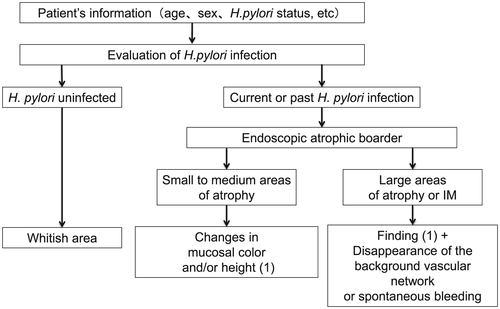

The clinically most important finding in diagnosing gastric cancer is atrophic changes in the gastric mucosa resulting from prolonged H. pylori infection.47-49 Atrophy of the gastric corpus and intestinal metaplasia occurs in a multifocal fashion in the fundus gland mucosa, and gradually extends to cover a greater area, eventually resulting in replacement of the entire fundus gland mucosa by atrophic and intestinal metaplastic mucosa.50 The border line of the mucosa devoid of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia (the F line) produced by the continuous presence of the fundus gland mucosa is almost consistent with the endoscopic atrophic border proposed by Kimura-Takemoto et al. (Fig. 5).51 Therefore, the inside of the endoscopic atrophic border corresponds to the fundus gland mucosa devoid of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Outside the border, there is an intermediate zone consisting of a mixture of multifocal atrophic and intestinal metaplastic mucosa and normal fundus gland mucosa, in addition to areas of atrophic and intestinal metaplastic mucosa having no fundus glands (Figs 6-8). Therefore, undifferentiated carcinoma often originates from the region inside the endoscopic atrophic border or the intermediate zone (vicinity of the atrophic border).52 In contrast, well-differentiated carcinoma often arises from the external region of the endoscopic atrophic border.

Histopathological types of EGC are associated with the morphological type and color of EGC on white-light images. Most elevated EGC are of the differentiated type and some gastric superficial elevated-type EGC and adenomas appear whitish. Among the flat or depressed-type EGC, differentiated-type cancers look reddish, whereas undifferentiated types appear whitish because of a difference in hemoglobin content (i.e. variations in vascular density).53 Therefore, using the location, morphological type, and color of an EGC, the histological type of EGC can be predicted. Thus, endoscopic evaluation of the gland atrophic border (the F line) is very useful for diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

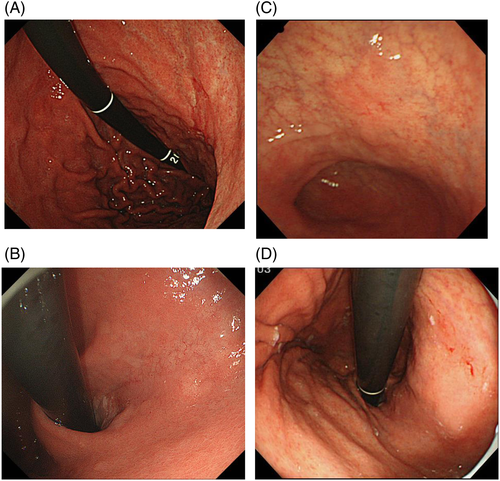

If there is moderately atrophic mucosa in the background, the lesion is usually located in the atrophic border. In particular, changes in the gastric angle and posterior wall of the lower gastric corpus are apt to be overlooked unless the observer is careful (Fig. 9A). Minute mucosal changes in the lesser curvature of the cardia are also difficult to find, so that observation from a short distance is necessary (Fig. 9B). Lesions are often found as slight concavities by a delicate change in color tone or by observation from a different angle.

It is difficult to find gastric cancer in the gastric mucosa accompanied by severely atrophic mucosa or intestinal metaplasia. Well-differentiated carcinoma occurs frequently in atrophic mucosa, whereas undifferentiated carcinoma often occurs in the border of the atrophy or non-atrophic fundus gland mucosa. The presence of gastric cancer may be recognized by slight changes in color tone or differences in concavity and convexity, but it is not rare to have no choice but to eventually depend on biopsy for diagnosis (Fig. 9C,D). Steps to make a diagnosis of gastric cancer on the basis of H. pylori infection and atrophy of the gastric mucosa are roughly described in Figure 10.

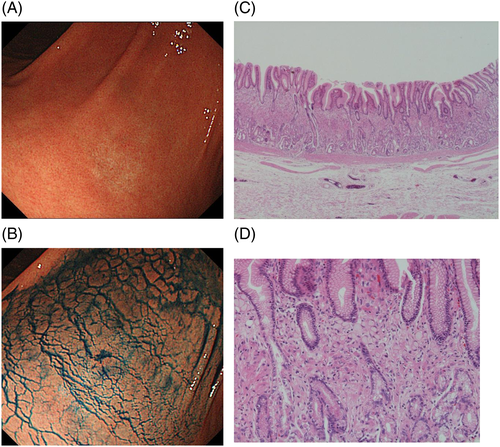

Observation of gastric mucosa with attention paid to possible intestinal metaplasia as a risk marker for gastric cancer

Chronic infection with H. pylori causes molecular alterations in the gastric mucosa and transforms the mucosa into the intestinal phenotype.54 Intestinal metaplasia is closely associated with a high risk of development of gastric cancer.55 On white light images, some intestinal metaplasia appears slightly elevated with whitish patches (Fig. 11A). Narrow-band imaging (NBI) further reveals intestinal metaplasia by its whitish color (Fig. 11B). Most intestinal metaplasia exists as a flat mucosa with subtle discoloration. In such cases, magnifying NBI is useful to make a diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia. In magnifying NBI images, a fine blue–white line of light is observed on the crests of the epithelial surface/gyri (light blue crest) of intestinal metaplasia (Fig. 11C).56 The light blue crest is thought to be caused by the reflection of short wavelength light at the brush border on the surface of the intestinal metaplasia.

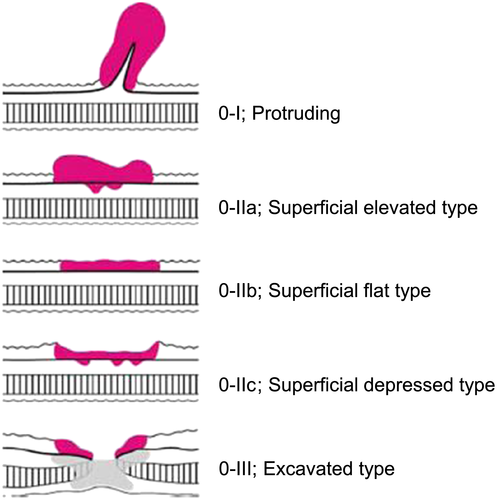

Characteristic Endoscopic Findings of EGC

Endoscopists who have no knowledge of what EGC looks like cannot find EGC even if they follow proper procedures. The starting point of detecting EGC is to know typical endoscopic findings and pathological findings of EGC. The typical macroscopic form of gastric cancer with the depth of invasion remaining within the submucosal layer is expressed as ‘superficial type (type 0)’ (Fig. 12).57 These types of EGC are basically seen in patients with H. pylori infection, but some types of EGC that develop in H. pylori-uninfected patients show distinctive morphology. One of the most typical EGC in H. pylori-uninfected patients is signet ring-cell carcinoma. This type of EGC, when it is discovered at a very early stage, hardly shows any morphological changes but pale faded color. This type of cancer cell sometimes extends subepithelially to the surrounding mucosa from an endoscopically recognized lesion; therefore, it is necessary to take biopsy specimens from the surrounding mucosa to map the tumor extension (Fig. 13). Moreover, because signet ring-cell carcinoma sometimes exists only in the middle layer of the lamina propria that is covered with normal foveolar epithelium, it is important to attempt to obtain enough deep biopsy specimens that contain the muscular mucosae with large forceps. Another characteristic type of the EGC in H. pylori-uninfected patients is adenoma of fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type). It develops in non-atrophic mucosa (90%), shows submucosal tumor shape (60%) and whitish color (70%) and has dilated vessels with branching architecture (50%).

Knack of Biopsy

There have been few reports on the clinically relevant number of biopsy specimens and suitable biopsy forceps in diagnosing EGC. Although the acquisition of six to eight biopsy specimens is recommended in Europe and the USA,58 it has been reported in Japan and South Korea that there is no particular change in the diagnostic accuracy as long as at least two biopsy specimens are taken.59, 60 This difference may be derived from the fact that targeted biopsy from more suspicious areas based on endoscopic findings, rather than random biopsy from the entire lesion, is conducted in Japan. Unfortunately, biopsies have been conducted according to customary practice, and no studies have been carried out to examine the number of biopsy specimens desirable as a quality indicator for accurate diagnosis of gastric cancer. Recent investigations have been focused only on the number of biopsy specimens suitable for molecular biological diagnosis.61

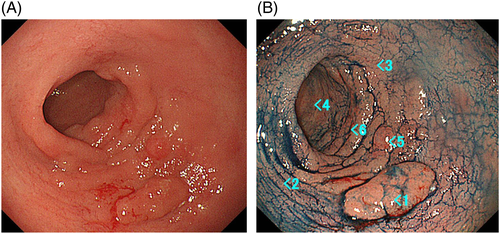

From Figure 14A, it is apparent that there is an aggregation of an elevated lesion in the greater curvature of the pyloric antrum. It is probably possible to diagnose by scattering indigocarmine that the lesion is regional to a certain extent, and is highly likely to be an epithelial tumor (i.e. EGC). Although #2 and #4 of Figure 14B are highly likely not to be tumors, the extent of resection varied widely according to whether the extension of the lesion would exceed #3 or remain within #6. As a result, #3 was non-neoplastic, and the extent of resection was up to #6. Thus, clinicians are required to conduct thoughtful biopsies. In addition, it is desirable to submit biopsy specimens for pathological analysis by putting one specimen from one site into one bottle to allow subsequent one-on-one correspondence.

Necessary Records of Findings (Description, Review, Sharing, Extend Capability, Repeated Improvement)

It is important to share pertinent clinical information with the pathologist to increase the accuracy of the pathological diagnosis of biopsy tissue. The pathologist cannot make an accurate diagnosis if there are only writings such as ‘redness’, ‘erosion’, or ‘exclusion of malignancy’ in the column of the clinical diagnosis/request form. At a minimum, the following information should be provided: what the endoscopic findings are, the location from which the biopsy was taken, what the endoscopic diagnosis is, and what is being asked for in the pathological diagnosis (Table 2). Detailed request forms enable us to review and reflect on the reasons why the biopsy was taken, and what information is needed. Following this process is very useful for improvement of diagnostic techniques.

| Observation of gastric mucosa | Presence/absence of RAC and observation of the gastric angle. | |||||

| Presence/absence of fundus gland polyps. | ||||||

| Redness on ridge line (lesser curvature of the gastric corpus). | ||||||

| Presence/absence and severity of mucosal atrophy. | ||||||

| Swelling and redness of the greater curvature of the gastric corpus. | ||||||

| Presence/absence of xanthoma. | ||||||

| Intestinal metaplasia. | ||||||

| Nodular gastritis (particularly in the young). | ||||||

| Description of findings | Color tone of mucosa (redness, faded color) | Site | Atrophic/non-atrophic mucosa | Vague/distinct border | Elevation/concavity | Size |

| Convexity and concavity | Site | Atrophic/non-atrophic mucosa | Color tone (normal, redness, faded color) | Vague/distinct border | Size | |

| Biopsy | Site | Site of the recognized abnormal mucosa | Differential diagnosis | Issues to be confirmed histologically (or provision of information for the pathologist) | To what extent is malignancy clinically suspected | |

- RAC, regular arrangement of collecting venules.

Advances in high-resolution electron endoscopy and routine implementation of tissue biopsy have enabled non-experts to easily detect EGC that has no specific findings of gastric cancer and thus could be diagnosed only by biopsy. However, in order to accurately detect initial lesions not by beginner's luck or by incidental diagnosis, but by steady techniques, it is important to implement theory-based observation (what the eyes see) and instantly relate the observation to critical analysis based on past experience and knowledge (what the brain knows) during the examination.

Conclusion

The primary goal of screening for gastric cancer is to detect neoplasms at an early stage. This can provide a unique opportunity to improve patient outcomes. While there are several challenges, cognitive knowledge, training, use of standardized grading systems, high-definition white-light endoscopy, and meticulous examination techniques are of paramount importance to improve detection of subtle lesions during upper endoscopy. The key concept for screening gastroscopy is that the eyes can only see what the brain knows.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Professor Philip WY Chiu, Department of Surgery, Institute of Digestive Disease, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, for his kind cooperation and suitable advice in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.